Constitutive Notch activation is required for the proliferation of a subgroup of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). Downstream pathways that transmit pro-oncogenic signals are not well characterized. To identify these pathways, protein microarrays were used to profile the phosphorylation state of 108 epitopes on 82 distinct signaling proteins in a panel of 13 T-cell leukemia cell lines treated with a gamma-secretase inhibitor (GSI) to inhibit Notch signals. The microarray screen detected GSI-induced hypophosphorylation of multiple signaling proteins in the mTOR pathway. This effect was rescued by expression of the intracellular domain of Notch and mimicked by dominant negative MAML1, confirming Notch specificity. Withdrawal of Notch signals prevented stimulation of the mTOR pathway by mitogenic factors. These findings collectively suggest that the mTOR pathway is positively regulated by Notch in T-ALL cells. The effect of GSI on the mTOR pathway was independent of changes in phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and Akt activity, but was rescued by expression of c-Myc, a direct transcriptional target of Notch, implicating c-Myc as an intermediary between Notch and mTOR. T-ALL cell growth was suppressed in a highly synergistic manner by simultaneous treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and GSI, which represents a rational drug combination for treating this aggressive human malignancy.

Introduction

Members of the conserved Notch family of transmembrane receptors are critically involved in the control of differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis in numerous cell types (reviewed in Artavanis-Tsakonas et al1 ). Binding of the extracellular domain of Notch to ligands of the Delta-Serrate-Lag2 (DSL) family initiates 2 successive proteolytic cleavages.2 The second cleavage, which is catalyzed by the γ-secretase complex, releases the intracellular domain of Notch (ICN) into the cytoplasm, from which it translocates to the nucleus and up-regulates transcription of Notch-regulated genes (eg, the hairy/enhancer-of-split [HES] gene family).3 γ-Secretase inhibitors (GSIs) suppress Notch signaling by blocking the activity of the multimeric γ-secretase complex.4

Notch has been implicated in the tumorigenesis of a growing number of hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.2,5 Depending on the specific Notch paralog and the cell type, extracellular environment, and signal intensity, Notch can transmit either pro-oncogenic or tumor-suppressive signals.2,5 There is strong evidence for a pro-oncogenic role for Notch-transduced signals in the development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) in mice and humans. Transfer of bone marrow cells stably transduced with ICN1 into irradiated mice resulted in the development of T-cell leukemia with 100% penetrance.6 Activating mutations in Notch1 are found in 50% to 60% of human T-ALL samples7 and have subsequently been detected in many different murine T-ALL models.8,,–11 Of importance, blockade of Notch signals with GSI arrests a subset of human T-ALL cell lines at the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle.7

Notch modulates the activity of signaling pathways through transcriptional regulation of its target genes. Signaling pathways downstream of Notch that transmit pro-oncogenic signals in T-ALL are poorly defined. Studies in murine models of Notch-induced T-cell leukemia and thymocyte differentiation have implicated several signaling intermediates including pre-T-cell receptor,12,13 Lck,13,14 protein kinase Cθ,13 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K),14,15 Akt/protein kinase B,14,15 extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2,16 and nuclear factor κB,13,17 as possible downstream regulators of Notch. The relevance of these and other signaling proteins in the control of human T-ALL cell proliferation is an important unsettled issue.

To explore these issues, we used reverse phase protein (RPP) microarrays to profile the phosphorylation state of 108 distinct epitopes on 82 signaling proteins in a panel of 13 human T-cell leukemia lines.18,19 We compared the phosphorylation profile of cells treated with compound E, a highly potent GSI, with vehicle-treated (DMSO) controls. We also profiled the abundance of 18 proteins irrespective of their phosphorylation state. Strikingly, we found that GSI treatment suppressed the phosphorylation of multiple signaling proteins in the mTOR pathway in a Notch-specific manner. The mTOR pathway plays a central role in sensing mitogenic and nutritional cues from the environment and relaying this information to downstream effectors that control protein synthesis and cell growth. Our findings indicate that the mTOR pathway also receives activating signals from Notch. Of importance, simultaneous blockade of the mTOR and Notch pathway with small molecule inhibitors resulted in synergistic suppression of T-ALL growth. The use of this drug combination represents a novel therapeutic approach for Notch-dependent cancers.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and GSI treatment

All cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM GlutaMAX (Invitrogen), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 37°C under 5% CO2. Characteristics of the 13 cell lines used in this study are presented in Table S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

To inhibit Notch signaling, cells in logarithmic growth were grown in the presence of either compound E (Axxora, San Diego, CA) at 1 μM or DAPT (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) at 10 μM. Mock-treated cultures were cultured in the presence of vehicle (DMSO) at a final concentration of 0.01% for compound E or 0.04% for DAPT.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were pelleted, washed in PBS, and resuspended in ice-cold 70% ethanol. The cells were fixed overnight, washed in FACS buffer, and treated with 1 mg/mL RNase A (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at 37°C. One milliliter propidium iodide (10 μg/mL; Sigma) was then added to each tube for 30 minutes at room temperature. DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScan; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The Cell Cycle analysis platform in FlowJo version 7.0 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) was used to determine the fraction of cells in each phase of the cell cycle.

Lysate preparation and RPP microarray fabrication

At the end of the incubation period with GSI or DMSO, cells were pelleted and washed once in ice-cold PBS. Following resuspension in a small volume of PBS, the cells were lysed by adding an equal volume of 2 × lysis buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS (wt/vol), 10% glycerol (vol/vol), 2% 2-mercaptoethanol (vol/vol), 5 mM EDTA, Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (1:5 dilution of stock solution) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (1:16 dilution of stock solution) (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and immediately snap-frozen. The samples were then boiled for 10 minutes, cooled to 23°C, and centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 minutes. The upper 90% of the supernatant was transferred to a new tube for long-term storage at −80°C. GSI- and mock-treated lysate samples were adjusted to contain the same concentration of total protein, as measured using the Quant-iT Protein Assay kit (Invitrogen), before printing.

To prepare source plates for microarray printing, samples were added to wells (10 μL/well) in a 384-well polypropylene PCR plate (Corning, Acton, MA). Lysates were printed using a contact-printing VersArray ChipWriter Compact system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) fitted with solid spotting pins. Lysates were arrayed on single-pad nitrocellulose-coated slides (FAST slides; Whatman, Florham Park, NJ). After printing, the slides were dried for 24 hour at 23°C before further processing.

Antibodies

A panel of phosphorylation-specific antibodies was chosen that provides representation of the major known signaling pathways (Table S2). Antibodies were further selected based on their epitope specificity, as determined on Western blots performed within labs at Stanford University and elsewhere (eg, AbMiner20 and AfCS-Nature Signaling Gateway).

Array processing

Microarray slides were assembled into FAST frames (Whatman) using single-well chambers to facilitate array processing. The arrays were first rinsed in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) and blocked in a 3% casein solution for 3 hours. Blocked slides were probed with primary antibodies diluted in PBST supplemented with 20% FCS (PBST/FCS) for 12 hours at 4°C. Dilution factors are listed in Table S2. Slides were then washed extensively with PBST and probed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated donkey anti–rabbit IgG or anti–mouse IgG antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 45 minutes at 23°C. Dilution factors for secondary antibodies are listed in Table S2.

To amplify signals, arrays were incubated in 1 × BAR reagent supplied in the Amplified Opti-4CN Substrate kit (Bio-Rad) for 10 minutes. Slides were then extensively washed with PBST supplemented with 20% (vol/vol) DMSO followed by PBST alone. To detect bound biotin, arrays were probed with streptavidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen) for 1 hour at 23°C. Dilution factors for the dye are listed in Table S2. Stained slides were washed with PBST, rinsed under deionized water, and dried under desiccation for a minimum of 1 hour before scanning.

Image analysis and data acquisition

Microarray images were captured at 10-micron resolution with a GenePix 4000B scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) using the 635-nm laser and 670DF40 emission filter. GenePix Pro Ver 6.0 (Molecular Devices) was used to determine the median fluorescent intensity of each spot and its surrounding background pixels. The median intensity value (background-subtracted) of the 6 replicate spots was used for further calculations. Three serial dilutions (1:1, 1:3, and 1:9) were printed for each treatment and cell line. To obtain a single value representing the overall expression of the analyte in question, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) in a plot with median fluorescent intensity on the Y-axis and dilution factor on the X-axis. The ratio of the AUC in GSI-treated samples to the AUC in mock-treated samples was used for further mathematical manipulations and statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Ratios were logged in base 2 and median centered for each cell line. Significance analysis of microarrays (SAM; http://www-stat.stanford.edu/∼tibs/SAM/) was used to determine significant changes in phosphorylation and total protein levels. The 2-class unpaired platform was used. GSI-sensitive cell lines were defined as one class and GSI-resistant lines as the comparison class. A stringent q-value cutoff of 2.5% was chosen to define significance. Ranking was based on the (d) score generated by SAM.

ICN1, DN-MAML1, and c-MYC retroviral transduction

Cell lines were transduced with pseudotyped, replication-defective MSCV retroviruses, which coexpress GFP and genes of interest from a single bicistronic RNA transcript containing an internal ribosomal entry sequence.4 The MigRI constructs for ICN1,21 DN-MAML1,4 and c-Myc22 have been described. Following transduction, GFP+ cells were sorted to 90% to 95% purity on a FACSVantage (BD Biosciences) and used for further analysis. In the experiment shown in Figure S2, transduced cells were selectively analyzed based on GFP expression without sorting.

Phospho-flow cytometry analysis

At each time point indicated in Figure 4, cells were removed from the flask and immediately fixed in 1.6% formaldehyde. After incubation at 37°C for 15 minutes, the cells were centrifuged, permeabilized in ice-cold 90% methanol and stored at −20°C. All samples were subsequently processed in parallel. Cells were washed twice in FACS buffer and resuspended in FACS buffer containing 1:50 dilution of an anti–phospho-S6 RP rabbit monoclonal antibody (clone 2F9; Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). After incubation at 23°C for 1 hour, the cells were washed in FACS buffer, and stained with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated donkey anti–rabbit IgG (0.4 μg/tube) (Invitrogen) for 45 minutes at 23°C in the presence of RNase A (100 μg/tube) (Sigma). After washing twice with FACS buffer, the cells were resuspended in 500 μL propidium iodide (10 μg/mL) (Sigma), incubated at 23°C for 15 minutes to stain DNA content, and analyzed on a flow cytometer (FACScan).

In the experiment shown in Figure 6D, cell lines were stained as in Figure 4 using the same anti–phospho-S6 RP antibody and an anti–phospho-Akt (Ser473) rabbit monoclonal antibody at 1:100 dilution (clone 193H12; Cell Signaling Technologies), followed by a phycoerythrin (R-PE)–conjugated donkey antirabbit antibody.

Drug synergism assay and combination index (CI) calculations

Viable T-ALL cells (1–4 × 104) were incubated in each well of a 96-well flat-bottom plate in the presence of drugs in a culture volume of 180 μL. Cells were exposed to compound E alone, rapamycin alone, or both drugs at the indicated concentrations for 5 days. The molar ratio of compound E to rapamycin was constant at 1000:1. A set of wells containing cells in the absence of drugs was used to determine the baseline level of proliferation (fraction affected = 0). Another set of wells with no cells added was used to determine the theoretical maximum level of effect (fraction affected = 1). At the end of the incubation period, the number of viable cells in each well was determined by adding 30 μL the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution reagent (Promega, Madison, WI), incubating the cells at 37°C degrees for 2 to 4 hours, and measuring the absorbance at 490 nm. The inhibitory effect of each drug or drug combination was reported as a “fraction affected” value between 0 and 1. CalcuSyn Version 2.0 (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was used to determine combination index (CI) values that reflect the degree of synergism between 2 drugs. CI values less than 1 reflect synergistic activity.

Results

GSI treatment induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in a fraction of T-ALL cell lines

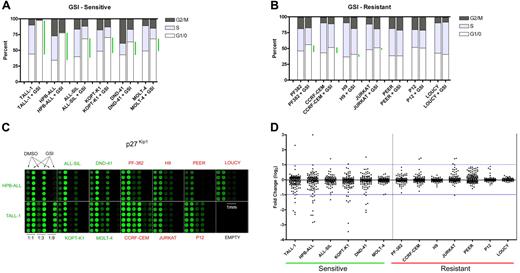

We first established the level of sensitivity of 13 T-ALL cell lines to treatment with the GSI compound E for 7 days (Figure 1A-B). For purposes of applying the SAM algorithm, which relies on a comparison of 2 classes, we defined responsive cell lines as those showing an increase of 20% or more in the fraction of cells in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle. The effects of compound E on cell cycling for 5 of the 6 cell lines (TALL-1, HPB-ALL, ALL-SIL, KOPT-K1, DND-41) were previously confirmed to be due to Notch1 inhibition, based on (1) rescue of each cell line from GSI blockade by ICN1 transduction; and (2) phenocopying of the GSI effect by DN-MAML1,7 which is a highly specific inhibitor of CSL/ICN binary complexes.4,7,23 All sensitive cell lines except for TALL-1 harbor activating Notch1 mutations.7 The remaining 7 cell lines were relatively resistant to Notch inhibition, which was defined as an increase in the G0/G1 fraction of 10% or less (Figure 1B). The resistant cell lines PF-382, CCRF-CEM, and P12 also harbor Notch1 mutations,7 yet do not respond to Notch inhibition for unclear reasons. Both JURKAT and LOUCY harbor normal NOTCH1 alleles, whereas the NOTCH1 mutational status of PEER and H9 has not been determined. Exposure to compound E for 5 to 7 days did not cause increased cell death (Figure S1, and data not shown).

Reverse phase protein (RPP) microarray profiling of Notch signals in T-ALL cell lines. (A) Six γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI)–sensitive T-ALL cell lines were treated with 1 μM compound E, a potent GSI, or vehicle (DMSO) for 7 days. Cell cycle distribution was determined based on DNA content of propidium iodide–stained populations. Green bars highlight the difference between mock- and GSI-treated cells in the G0/G1 fraction. (B) Cell cycle analysis of 7 GSI-resistant cell lines. (C) Lysates derived from GSI- and mock-treated cells were diluted (1:1, 1:3, 1:9) and printed on nitrocellulose-coated slides in 6 replicates. Fluorescent image of a representative RPP microarray probed with an antibody specific for the CDK inhibitor, p27Kip1, and stained with Alexa Fluor 647 is shown. Each subarray contains lysates derived from a single cell line. For the sole purpose of presentation, brightness and contrast were adjusted equivalently across the entire array to highlight differences in feature intensities. (D) Presentation of 133 phospho-protein or total protein fold change measurements (GSI/DMSO) for each cell line as a scatter plot. Each dot represents an individual measurement. Scatter plots of sensitive cell lines are on the left side and resistant cell lines on the right. See “Materials and methods” for details in the calculation of fold change. All data points are logged in base 2 and median-centered for their corresponding cell line. The blue horizontal lines are arbitrarily placed to assist the comparison of scatter plots.

Reverse phase protein (RPP) microarray profiling of Notch signals in T-ALL cell lines. (A) Six γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI)–sensitive T-ALL cell lines were treated with 1 μM compound E, a potent GSI, or vehicle (DMSO) for 7 days. Cell cycle distribution was determined based on DNA content of propidium iodide–stained populations. Green bars highlight the difference between mock- and GSI-treated cells in the G0/G1 fraction. (B) Cell cycle analysis of 7 GSI-resistant cell lines. (C) Lysates derived from GSI- and mock-treated cells were diluted (1:1, 1:3, 1:9) and printed on nitrocellulose-coated slides in 6 replicates. Fluorescent image of a representative RPP microarray probed with an antibody specific for the CDK inhibitor, p27Kip1, and stained with Alexa Fluor 647 is shown. Each subarray contains lysates derived from a single cell line. For the sole purpose of presentation, brightness and contrast were adjusted equivalently across the entire array to highlight differences in feature intensities. (D) Presentation of 133 phospho-protein or total protein fold change measurements (GSI/DMSO) for each cell line as a scatter plot. Each dot represents an individual measurement. Scatter plots of sensitive cell lines are on the left side and resistant cell lines on the right. See “Materials and methods” for details in the calculation of fold change. All data points are logged in base 2 and median-centered for their corresponding cell line. The blue horizontal lines are arbitrarily placed to assist the comparison of scatter plots.

RPP microarray analysis identifies changes that occur in sensitive cell lines

Equal amounts of total protein from lysates of cell lines treated with compound E (1 μM) or vehicle for 7 days were serially diluted and printed with 6-fold redundancy on microarray slides. Lysate arrays were probed, processed, and analyzed as described.18 A representative array probed with a modification-independent antibody specific for the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor, p27Kip1, is shown (Figure 1C). Staining for p27Kip1 was clearly increased in sensitive cell lines treated with GSI, but unchanged in resistant cells. There was no change in the levels of Lck, the expression of which is unaffected by GSI (data not shown). Global presentation of all the data points on scatter plots revealed clear changes in the phosphorylation and abundance of a number of signaling proteins in sensitive lines (Figure 1D), whereas resistant cell lines demonstrated much smaller degrees of scatter.

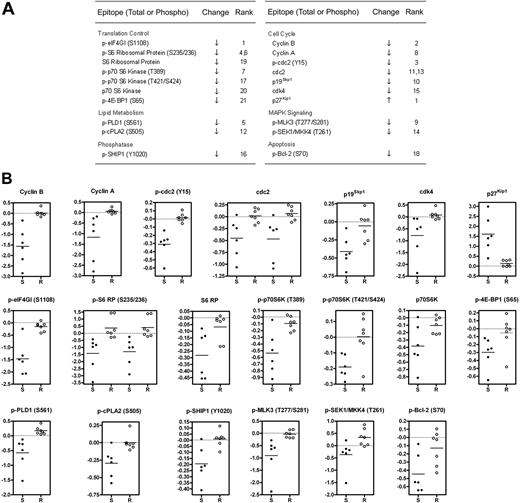

The main goal of the microarray screen was to identify changes in signaling proteins that occurred preferentially in GSI-sensitive cells. To this end, we used the significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) algorithm,24 which generated a list of 12 phospho-epitope and 8 total protein changes with a stringent q-value cutoff of 2.5% (Figure 2A). Raw ratiometric data are presented in Table S3. Although some degree of overlap was observed for a few analytes (eg, p-SEK1/MKK4), scatter plots of SAM-identified changes revealed a clear delineation between sensitive and resistant cells (Figure 2B).

Identification of changes in phosphorylation and total protein levels that preferentially occur in GSI-sensitive cell lines. (A) Significant list of phospho-epitopes and proteins identified by significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) along with their direction of change and (d)-score rank. See “Materials and methods” for details. When 2 ranks are shown for a particular epitope, 2 distinct antibodies with the same specificity were used. (B) Presentation of fold change measurements as scatter plots for SAM-identified analytes listed in (A). Each dot represents an individual cell line. S denotes sensitive cell lines. R denotes resistant lines. All fold-change data points are logged in base 2 and median-centered for their corresponding cell line. Horizontal line indicates the mean fold change of the group. For cdc2 and p-S6 RP, 2 distinct antibodies were used.

Identification of changes in phosphorylation and total protein levels that preferentially occur in GSI-sensitive cell lines. (A) Significant list of phospho-epitopes and proteins identified by significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) along with their direction of change and (d)-score rank. See “Materials and methods” for details. When 2 ranks are shown for a particular epitope, 2 distinct antibodies with the same specificity were used. (B) Presentation of fold change measurements as scatter plots for SAM-identified analytes listed in (A). Each dot represents an individual cell line. S denotes sensitive cell lines. R denotes resistant lines. All fold-change data points are logged in base 2 and median-centered for their corresponding cell line. Horizontal line indicates the mean fold change of the group. For cdc2 and p-S6 RP, 2 distinct antibodies were used.

Notch inhibition suppresses phosphorylation of proteins in the mTOR pathway

Strikingly, the screen identified a panel of changes in the phosphorylation of proteins in the mTOR pathway, which is critically involved in translation control (Figure 2A). To confirm this potentially important connection between Notch and mTOR, we performed conventional Western blots for phospho-S6 RP, phospho-p70 S6 kinase at 2 epitopes, phospho-4E-BP1, and their respective total protein levels with a set of independent lysates. The blots showed the same phosphorylation changes that were detected on microarrays (Figure 3A). Although a minor reduction in the abundance of each of the proteins was observed, especially in TALL-1 and HPB-ALL, the magnitude of change in phosphorylation was much greater, as confirmed using quantitative densitometry. Transduction of the sensitive cell lines with ICN1, which lies downstream of the GSI blockade, fully “rescued” the phosphorylation changes in S6 RP, p70 S6 kinase, and 4E-BP1 (Figure 3B), which is consistent with previous experiments showing that ICN1 also rescues GSI-sensitive cell lines from growth arrest.7 Suppression of S6 RP phosphorylation was also induced by transduction of dominant-negative mastermind-like-1 (DN-MAML1), a 62–amino acid peptide that forms a transcriptionally inert complex with ICN and its nuclear target, CSL (Figure S2A-B).4,7 These results indicate that the effects of GSI on mTOR effectors are mediated through Notch inhibition.

Notch inhibition suppresses phosphorylation of effectors in the mTOR pathway. (A) Five GSI-sensitive cell lines were exposed to either GSI (compound E) or vehicle (DMSO) for 7 days. After the incubation period, whole-cell lysates were prepared and equivalent amounts of total protein were loaded per lane on a polyacrylamide gel for Western blot analysis using the panel of antibodies shown on the left. (B) Similar experiment as in panel A except the cell lines were stably transduced with retroviruses expressing ICN1. The values shown below each blot represent ratios (phospho/total) of calibrated densitometry readings normalized to mock-treated (DMSO) control samples.

Notch inhibition suppresses phosphorylation of effectors in the mTOR pathway. (A) Five GSI-sensitive cell lines were exposed to either GSI (compound E) or vehicle (DMSO) for 7 days. After the incubation period, whole-cell lysates were prepared and equivalent amounts of total protein were loaded per lane on a polyacrylamide gel for Western blot analysis using the panel of antibodies shown on the left. (B) Similar experiment as in panel A except the cell lines were stably transduced with retroviruses expressing ICN1. The values shown below each blot represent ratios (phospho/total) of calibrated densitometry readings normalized to mock-treated (DMSO) control samples.

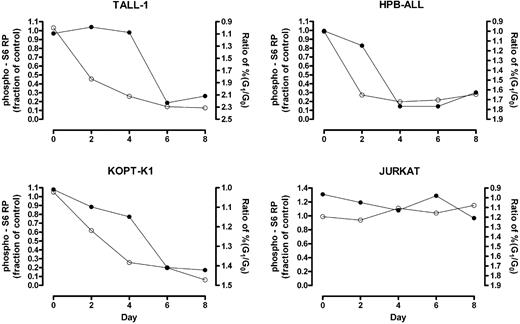

Phosphorylation of mTOR effectors fluctuates with the phase of the cell cycle (data not shown); therefore, changes detected using “bulk lysates” might represent an effect of cell-cycle arrest rather than a primary effect on mTOR targets. To clarify this issue, we used intracellular flow cytometry to measure the kinetics of S6 RP dephosphorylation in G0/G1-gated cells following exposure to GSI. Notch inhibition produced rapid dephosphorylation of S6 RP in GSI-sensitive cell lines (HPB-ALL, TALL-1, and KOPT-K1) prior to the onset of G0/G1-arrest (Figure 4), arguing for a primary effect of Notch signaling on the activation status of mTOR effectors.

S6 RP dephosphorylation in G0/G1-gated cells occurs prior to substantial cell cycle arrest. Cells were exposed to GSI (DAPT) or vehicle (DMSO) for the indicated amount of time. At each time point, cells were intracellularly stained with an antibody specific for phospho-S6 RP and their DNA contents measured by propidium iodide staining. Cells in the G0/G1 fraction were gated based on DNA content and their level of S6 RP phosphorylation was determined. The fraction of the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of GSI-treated cells to the MFI of mock-treated cells was calculated and plotted over time (open circles, left Y-axis). The ratio of the percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase in GSI-treated populations to that in mock-treated populations was measured over 8 days to monitor cell cycle arrest (solid circles, right Y-axis; axis is reversed to facilitate comparison between the 2 graphs). Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

S6 RP dephosphorylation in G0/G1-gated cells occurs prior to substantial cell cycle arrest. Cells were exposed to GSI (DAPT) or vehicle (DMSO) for the indicated amount of time. At each time point, cells were intracellularly stained with an antibody specific for phospho-S6 RP and their DNA contents measured by propidium iodide staining. Cells in the G0/G1 fraction were gated based on DNA content and their level of S6 RP phosphorylation was determined. The fraction of the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of GSI-treated cells to the MFI of mock-treated cells was calculated and plotted over time (open circles, left Y-axis). The ratio of the percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase in GSI-treated populations to that in mock-treated populations was measured over 8 days to monitor cell cycle arrest (solid circles, right Y-axis; axis is reversed to facilitate comparison between the 2 graphs). Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

Notch inhibition decreases cellular protein content and cell size

Signals downstream of mTOR control protein synthesis rate and cell size through regulation of ribosome biogenesis and translation initiation.25 As anticipated, given this association, GSI treatment decreased the amount of protein per cell (Figure S3) and the mean cell size of sensitive cell lines (Figure 5A). Both of these changes were rescued by ICN1 transduction, confirming that these effects of GSI are Notch-specific (data not shown). These conclusions are in line with other recent studies demonstrating that Notch inhibition reduces T-ALL cell size.22,26 The cell size response to GSI was a continuum, as several resistant cell lines also demonstrated a lesser decrease in cell size than sensitive lines. The magnitude of size reduction strongly correlated with the level of dephosphorylation at serine 389 on p70 S6 kinase (Figure 5B), providing a link between mTOR effector inhibition and cell size.

Notch inhibition reduces cell size. (A) The indicated cell lines were treated with GSI (compound E) or vehicle (DMSO) for 7 days. After the incubation period, relative size (forward scatter) of G0/G1-gated cells was determined by flow cytometry. Histograms with FSC on the X-axis are shown. (B) The magnitude of size reduction for each of the 13 tested lines was measured after exposure to GSI for 7 days and correlated with its corresponding suppression in p70 S6 kinase (T389) phosphorylation as measured using RPP microarrays. Size of GSI-treated cells is reported as a percentage of mock (DMSO)–treated cells on the X-axis. The level of phospho-p70 S6 kinase (T389) is shown on the Y-axis as the median-centered log2 ratio of GSI/DMSO-treated cells.

Notch inhibition reduces cell size. (A) The indicated cell lines were treated with GSI (compound E) or vehicle (DMSO) for 7 days. After the incubation period, relative size (forward scatter) of G0/G1-gated cells was determined by flow cytometry. Histograms with FSC on the X-axis are shown. (B) The magnitude of size reduction for each of the 13 tested lines was measured after exposure to GSI for 7 days and correlated with its corresponding suppression in p70 S6 kinase (T389) phosphorylation as measured using RPP microarrays. Size of GSI-treated cells is reported as a percentage of mock (DMSO)–treated cells on the X-axis. The level of phospho-p70 S6 kinase (T389) is shown on the Y-axis as the median-centered log2 ratio of GSI/DMSO-treated cells.

Stimulation of the mTOR pathway by mitogens requires concurrent Notch signals

mTOR integrates cues that control cellular growth, such as mitogenic growth factors (eg, insulin and insulin-like growth factors [IGFs]), amino acids, and glucose metabolism (ie, ATP/ADP ratio).25,27,28 When conditions are conducive to cellular growth, mTOR activity is up-regulated, leading to higher rates of protein translation. Our data suggest that mTOR also receives inputs from Notch. We favor a model in which Notch sends a permissive signal to mTOR, enabling responsiveness to mitogen-transduced signals, which are transmitted through components of the PI3K/Akt pathway.28 In support of this model, we found that the up-regulation of S6 RP phosphorylation in TALL-1 cells in response to stimulation with fetal calf serum or purified IGF-I is blunted when Notch signaling is inhibited (Figure 6A).

Effects of Notch on the mTOR pathway are independent of changes in Akt activity but dependent on c-Myc. (A) Notch inhibition blocks the induction of S6 RP phosphorylation in response to fetal calf serum (FCS) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) stimulation. TALL-1 cells were treated with GSI (DAPT) or vehicle (DMSO) for 6 days. The cells were then serum starved for 24 hours and subsequently stimulated with FCS (10%) or IGF-I (20 ng/mL) for an additional 24 hours. Wortmannin (50 nM) was added to the cells during the last hour of incubation. Cell lysates were prepared and equivalent amounts of protein were loaded per lane on a gel for Western blot analysis using the 2 antibodies shown. Expression of Hes-1 mRNA normalized to GAPDH in each sample was measured using quantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm inhibition of Notch activity. The values shown indicate the amount of Hes-1 mRNA relative to serum-starved mock-treated cells. GSI-treated (right panel) and DMSO control (left panel) samples were processed on the same blot. (B) Protein microarray ratiometric data for phospho-Akt (Ser473) and phospho-S6 RP in GSI-sensitive cell lines. Ratios (GSI/DMSO) are logged in base 2 and median-centered for each cell line. (C) GSI treatment abolishes S6 RP phosphorylation in the absence of changes in Akt and GSK3β phosphorylation. HPB-ALL and TALL-1 cells were treated with GSI (compound E) or vehicle (DMSO) for 3 days. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and equivalent amounts of proteins were loaded per lane for Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies on the left. The values shown below each blot represent ratios (phospho/total) of calibrated densitometry readings normalized to mock-treated (DMSO) control samples. (D) GSI-induced dephosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein is not dependent on changes in PI3K/Akt activity. HPB-ALL and T-ALL cells were exposed to either DMSO or 1 μM GSI (compound E) for 3 days. At the end of the 3-day period, cells were intracellularly stained with an antibody specific for either phospho-S6 RP or phospho-Akt (Ser 473) and analyzed using flow cytometry. Gates were placed around mock- and GSI-treated cell populations on forward and side scatter dot plots with equivalent levels of phospho-Akt staining. Phospho-S6 RP staining was compared between the 2 groups using the same gated populations. Each bar graph represents background-subtracted mean fluorescent intensity of the indicated phospho-epitope normalized to the corresponding value in mock-treated control cells. Error bars represent standard deviation. (E) Similar experiment as in Figure 3 except the cell lines were stably transduced with retroviruses expressing c-Myc. Blots were probed with the antibodies indicated on the left panel. The values shown below each blot represent ratios (phospho/total) of calibrated densitometry readings normalized to mock-treated (DMSO) control samples.

Effects of Notch on the mTOR pathway are independent of changes in Akt activity but dependent on c-Myc. (A) Notch inhibition blocks the induction of S6 RP phosphorylation in response to fetal calf serum (FCS) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) stimulation. TALL-1 cells were treated with GSI (DAPT) or vehicle (DMSO) for 6 days. The cells were then serum starved for 24 hours and subsequently stimulated with FCS (10%) or IGF-I (20 ng/mL) for an additional 24 hours. Wortmannin (50 nM) was added to the cells during the last hour of incubation. Cell lysates were prepared and equivalent amounts of protein were loaded per lane on a gel for Western blot analysis using the 2 antibodies shown. Expression of Hes-1 mRNA normalized to GAPDH in each sample was measured using quantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm inhibition of Notch activity. The values shown indicate the amount of Hes-1 mRNA relative to serum-starved mock-treated cells. GSI-treated (right panel) and DMSO control (left panel) samples were processed on the same blot. (B) Protein microarray ratiometric data for phospho-Akt (Ser473) and phospho-S6 RP in GSI-sensitive cell lines. Ratios (GSI/DMSO) are logged in base 2 and median-centered for each cell line. (C) GSI treatment abolishes S6 RP phosphorylation in the absence of changes in Akt and GSK3β phosphorylation. HPB-ALL and TALL-1 cells were treated with GSI (compound E) or vehicle (DMSO) for 3 days. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and equivalent amounts of proteins were loaded per lane for Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies on the left. The values shown below each blot represent ratios (phospho/total) of calibrated densitometry readings normalized to mock-treated (DMSO) control samples. (D) GSI-induced dephosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein is not dependent on changes in PI3K/Akt activity. HPB-ALL and T-ALL cells were exposed to either DMSO or 1 μM GSI (compound E) for 3 days. At the end of the 3-day period, cells were intracellularly stained with an antibody specific for either phospho-S6 RP or phospho-Akt (Ser 473) and analyzed using flow cytometry. Gates were placed around mock- and GSI-treated cell populations on forward and side scatter dot plots with equivalent levels of phospho-Akt staining. Phospho-S6 RP staining was compared between the 2 groups using the same gated populations. Each bar graph represents background-subtracted mean fluorescent intensity of the indicated phospho-epitope normalized to the corresponding value in mock-treated control cells. Error bars represent standard deviation. (E) Similar experiment as in Figure 3 except the cell lines were stably transduced with retroviruses expressing c-Myc. Blots were probed with the antibodies indicated on the left panel. The values shown below each blot represent ratios (phospho/total) of calibrated densitometry readings normalized to mock-treated (DMSO) control samples.

GSI treatment does not affect the phosphorylation and activity of Akt

One important mediator of mTOR activation is the PI3K/Akt pathway, which acts downstream of a number of growth factor receptors. Indeed, inhibition of PI3K activity with wortmannin blocked the stimulation of S6 RP by mitogens (Figure 6A). However, results from our microarray experiments do not support a model in which Notch activates mTOR through PI3K/Akt. Notch inhibition did not affect the phosphorylation of Akt at 2 epitopes important for kinase activity (Ser473 and Thr308), or the phosphorylation of Akt substrates (eg, GSK3β) in any of the 6 sensitive cell lines (Table S3; Figure 6B). We confirmed these array findings with Western blots probing for phospho-Akt (Ser473) and phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) in HPB-ALL and TALL-1, the 2 cell lines with the greatest sensitivity to GSI (Figure 6C). Phosphorylation of these epitopes was minimally affected under conditions in which the phosphorylation of S6 RP was abolished, suggesting that Notch activates mTOR through a PI3K/Akt-independent pathway. To further support this premise, we used flow cytometry to compare the level of S6 RP phosphorylation and phospho-Akt (Ser473) between mock- and GSI-treated cells in populations that were gated to contain equivalent levels of phospho-Akt. We found that S6 RP phosphorylation was suppressed in GSI-treated cells compared with mock-treated cells despite equivalent levels of activated Akt (Figure 6D).

Expression of c-Myc rescues the dephosphorylation of mTOR effectors

Our data suggest a model in which Notch stimulates mTOR activity through a pathway that is independent of PI3K and Akt. One direct transcriptional target of Notch1 that may play a role in this pathway is c-Myc, which can rescue growth arrest phenotypes produced by the blockade of Notch signals in a subset of human T-ALL cell lines.22 To test this hypothesis, we treated GSI-sensitive cell lines that were transduced with c-Myc and treated with GSI for 7 days. GSI is known to dramatically suppress c-Myc expression in untransduced cells within 1 to 2 days.22 Transduction of c-Myc reversed the GSI-induced dephosphorylation of S6 RP and p70 S6 kinase to varying degrees, with ALL-SIL, KOPT-K1, and DND-41 showing complete rescue, and TALL-1 and HPB-ALL partial rescue (Figure 6E). Of interest, the 2 cell lines that become fully resistant to GSI-induced growth arrest when transduced with c-Myc (KOPT-K1 and DND-41)22 also showed complete rescue of S6 RP and p70 S6K dephosphorylation by c-Myc.

Simultaneous inhibition of mTOR and Notch signals suppresses T-ALL growth synergistically

The mTOR pathway represents one of several pro-oncogenic pathways activated by Notch, and although GSI treatment suppressed the activity of the mTOR pathway, complete inactivation was not consistently observed (Figure 3A). These observations suggested that the combination of mTOR and Notch pathway inhibitors should act synergistically to inhibit T-ALL growth. To test this hypothesis, 12 T-ALL cell lines were exposed to varying concentrations of rapamycin, GSI (compound E), or both drugs at a constant molar ratio for 5 to 6 days (Figure 7). Treatment with rapamycin alone resulted in varying degrees of growth inhibition in 11 of 12 cell lines tested (the exception being the cell line P12), indicating a general requirement for mTOR in T-ALL growth. Treatment with GSI alone suppressed the growth of the sensitive T-ALL cell lines in a fashion that correlated with the sensitivity of each line to cell cycle arrest (compare Figure 7 and Figure 1A). Treatment with both drugs inhibited growth of the GSI-sensitive cell lines with a strong degree of synergy, as judged by the median-effect principle developed by Chou and Talalay.29 Of interest, although GSI treatment alone exerted minor effects on the growth of resistant cell lines, it also augmented the suppressive effects of rapamycin in 5 of the 6 GSI-resistant cell lines.

Synergistic suppression of T-ALL growth with rapamycin and GSI. GSI-sensitive cell lines (left panel) and -resistant cell lines (right panel) were cultured in the presence of varying concentrations of GSI (compound E), rapamycin, or combination of both drugs at a fixed molar ratio of 1000:1 (compound E/Rapamycin). The number of viable cells in each well was determined using a MTS-based assay at the end of a 5- or 6-day incubation period. See “Materials and methods” for details in the calculation of “fraction affected” and combination index (CI). Error bars represent standard deviation. Lines are placed at 0.25 to facilitate comparisons between graphs.

Synergistic suppression of T-ALL growth with rapamycin and GSI. GSI-sensitive cell lines (left panel) and -resistant cell lines (right panel) were cultured in the presence of varying concentrations of GSI (compound E), rapamycin, or combination of both drugs at a fixed molar ratio of 1000:1 (compound E/Rapamycin). The number of viable cells in each well was determined using a MTS-based assay at the end of a 5- or 6-day incubation period. See “Materials and methods” for details in the calculation of “fraction affected” and combination index (CI). Error bars represent standard deviation. Lines are placed at 0.25 to facilitate comparisons between graphs.

Discussion

To identify novel pro-oncogenic pathways regulated by Notch, we used RPP microarrays to screen for phosphorylation changes in a large number of signaling proteins in 13 T-ALL cell lines that show variable sensitivity to GSI. It was previously noted that sensitive cell lines undergo a slow onset (5-7 days) G0/G1 cell cycle arrest with GSI treatment,4,7 which is accompanied by a decrease in cell size,22,26 and that these changes are rescued by ICN1 and mimicked by DN-MAML1, indicating that they are mediated through Notch inhibition. As anticipated, we noted changes in the levels of a large number of cell cycle regulatory proteins (Figure 2A), including increases in p27Kip1, a CDK inhibitor, and decreases in cyclin B, cyclin A, cdc2 (also known as cdk1), p19Skp1, and cdk4. Reduced levels of BCL2 phosphorylation on S70 is also consistent with G0/G1 arrest, as phosphorylation at this site occurs in G2/M.30 However, cell cycle arrest is a late effect of GSI and ICN1 is short-lived and disappears within 24 hours of commencing GSI treatment,4,26 suggesting that cessation of growth may be a secondary effect of Notch inhibition.

One candidate pathway for mediating the proliferative effects of Notch that was revealed through our screen is the mTOR pathway (Figure 2A). mTOR is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine kinase that regulates cell growth and cell cycle progression through translation control.27,28 It exists as a multiprotein complex in combination with raptor and mLST8 to form mTORC1, or with rictor, mSin1, and mLST8 to form mTORC2.31 In response to growth factors and nutrients, mTORC1 activates the phosphorylation of downstream effectors such as 4E-BP1 and p70 S6 kinase. Exposure to rapamycin, a potent and specific inhibitor of mTORC1 kinase activity, induces dephosphorylation of 4E-BP1, p70 S6 kinase, and S6 ribosomal protein (S6 RP), a direct substrate of p70 S6 kinase.25,32 Phosphorylation of eIF4GI has also been shown to be sensitive to rapamycin.33 The profile of phosphorylation changes induced by GSI was strikingly similar to that of rapamycin. We have independently confirmed these effects of rapamycin in our T-ALL cell lines (data not shown). Of interest, GSI also induced dephosphorylation of phospholipase D1 (PLD1) at a residue that has been postulated to activate PLD1,34 an enzyme that in turn activates mTOR by generating phosphatidic acid.35 Of further interest, mTOR activity was preferentially inhibited in GSI-sensitive cell lines.

To confirm the effect of Notch inhibition on the mTOR pathway, we focused on one well-characterized downstream effector, S6 RP. GSI treatment in sensitive T-ALL cell lines induced rapid S6 RP dephosphorylation, which preceded the onset of cell cycle arrest, suggesting that changes in mTOR activity may be a primary mediator of growth arrest. Of importance, the effect of GSI on S6 RP phosphorylation was rescued by ICN1, and phenocopied by DN-MAML1, firmly implicating Notch signaling in regulation of this crucial effector of mTOR-mediated translational control. Given these findings and the well-characterized role of mTOR in the control of cell cycle progression, we conclude that Notch positively regulates the phosphorylation and activity of effectors in the mTOR pathway.

Further work will be needed to validate other aspects of the “GSI signature” that we identified on microarrays and link them with certainty to Notch, such as the observed changes in PLD1 phosphorylation. It is notable, however, that other work has linked Notch signals to metabolism and growth in T-ALL cells22,26 and normal developing thymocytes.15 Another important issue that remains unsettled is precisely how Notch interacts with the mTOR pathway. One possibility is through the PI3K/Akt pathway, which positively regulates mTOR and, when constitutively activated, can rescue certain aspects of T-cell development in the face of NOTCH1 deficiency.15 In addition, Sade et al showed that overexpression of ICN1 activated PI3K and Akt activity and increased the survival of Jurkat cells.14 Despite these findings, we did not observe changes in the phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream substrate GSK3β by several techniques including protein arrays, Western blots, and phospho-flow cytometry. Moreover, Notch inhibition did not result in cell death, again supporting a model in which Akt activity is unaffected (Figure S1). These results collectively suggest that Notch controls mTOR activity through a pathway independent of Akt. Discrepancy between our data and prior reports may be explained by the potential existence of mutations in T-ALL cells that constitutively stimulate high levels of PI3K/Akt activity, thereby uncoupling Notch from the Akt pathway.

DN-MAML1 is a specific inhibitor of the CSL/ICN transcriptional activation complex,4,23 which phenocopies the effects of GSI treatment of T-ALL cells. This strongly implies that the effects of Notch on the mTOR pathway are mediated through up-regulated transcription of target genes. Our present data suggest some ways in which this may occur, but also point to complexity and inter–cell line variation in the responsible circuits. One target gene that appears to be partially responsible is c-Myc, a recently described Notch1 transcriptional target that is an important regulator of cellular metabolism and translation.22,26,36,37 Enforced expression of c-Myc can fully rescue mTOR effectors from Notch withdrawal in a subset of T-ALL cell lines (ALL-SIL, KOPT-K1, and DND-41). This finding implicates c-Myc as an intermediary that connects Notch to mTOR. Although the precise mechanism by which c-Myc activates mTOR is unknown, the 2 pathways have previously been shown to cooperate in the formation of B-cell lymphomas.38 However, c-Myc is not the only effector, as TALL-1 and HPB-ALL are only partially rescued by c-Myc expression. The PI3K/Akt pathway is a second potential candidate pathway, but the absence of change in Akt or GSK3β phosphorylation argues against this possibility. A third candidate is PLD1, which activates mTOR activity through its metabolic product, phosphatidic acid. Although the mechanism of PLD1 regulation by Notch is unknown, it is intriguing that PLD1 trafficking and activity are modulated by a direct physical interaction with γ-secretase, suggesting that the Notch and PLD1 pathways are coordinately regulated.39,40 It will be of interest to explore the interaction between Notch and PLD1 pathways further, especially since PLD1 may also be a “druggable” target.

Although many molecular details of the Notch/mTOR connection remain to be clarified, our work points to the possible utility of combining Notch and mTOR pathway inhibitors. T-ALL cell lines appear to be sensitive to growth arrest by the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, and the addition of GSI synergistically enhances growth suppression, even in those cell lines that do not respond to GSI alone. Our data suggest that the mTOR pathway is targeted by both drugs at multiple levels. The Akt pathway may also be a target of rapamycin through a recently described inhibitory effect of the drug on the mTORC2 complex, which phosphorylates Akt at S473.41 Thus, the observed synergism may reflect the simultaneous inhibition of mTORC1, mTORC2, and Akt by rapamycin; and inhibition of the mTOR pathway through c-Myc and possibly other inputs such as PLD1 by GSI. Experiments are under way to investigate the relative contributions of each of these effects.

Despite growing interest in the use of rapamycin and related compounds for treating cancer, clinical trials have shown that their efficacy is highly variable depending on the cancer type.42 Moreover, the objective response rate was often low even for sensitive cancer types (eg, renal cell carcinoma).43 Our data suggest that concurrent administration of Notch inhibitors with rapamycin may improve response in those tumors in which the Notch pathway is active. Of note, single-agent trials of both Notch pathway inhibitors and rapamycin are currently enrolling patients or are planned in a number of cancers, including T-ALL. Our data provide rationale for second-generation combination drug trials in T-ALL and other malignancies, such as breast cancer, in which Notch signals have been implicated.37,44

Finally, as demonstrated in this study, protein microarrays have the potential to expedite the discovery of unexpected connections between signaling pathways. With the increasing number of commercially available and highly specific phospho-antibodies and further technical advances, the utility of protein microarrays will undoubtedly increase. As shown here, the ability to measure hundreds of samples in parallel on a single slide is a powerful discovery tool that can identify dysregulated signaling pathways in leukemia and other cancers.

The online version of this manuscript contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M.C. was involved in all aspects of the study and paper; A.P.W. performed experiments and contributed to the studydesign; R.T. provided expertise in statistical analysis; J.C.A. provided experimental samples, and contributed to the study design and paper; P.J.U. contributed to the study design and paper.

The labs of J.C.A. and P.J.U. contributed equally to this study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul J. Utz, Stanford University School of Medicine, Division of Immunology and Rheumatology, CCSR Bldg, Rm 2215A, 269 Campus Dr, Stanford, CA 94305; e-mail: pjutz@stanford.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal