Abstract

WHIM(warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, recurrent bacterial infection, and myelokathexis) syndrome is a rare immunodeficiency caused in many cases by autosomal dominant C-terminal truncation mutations in the chemokine receptor CXCR4. A prominent and unexplained feature of WHIM is myelokathexis (hypercellularity with apoptosis of mature myeloid cells in bone marrow and neutropenia). We transduced healthy human CD34+ peripheral blood–mobilized stem cells (PBSCs) with retrovirus vector encoding wild-type (wt) CXCR4 or WHIM-type mutated CXCR4 and studied these cells ex vivo in culture and after engraftment in a nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mouse xenograft model. Neither wt CXCR4 nor mutated CXCR4 transgene expression itself enhanced apoptosis of neutrophils arising in transduced PBSC cultures even with stimulation by a CXCR4 agonist, stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1 [CXCL12]). Excess wt CXCR4 expression by transduced human PBSCs enhanced marrow engraftment, but did not affect bone marrow (BM) apoptosis or the release of transduced leukocytes into PB. However, mutated CXCR4 transgene expression further enhanced BM engraftment, but was associated with a significant increase in apoptosis of transduced cells in BM and reduced release of transduced leukocytes into PB. We conclude that increased apoptosis of mature myeloid cells in WHIM is secondary to a failure of marrow release and progression to normal myeloid cell senescence, and not a direct effect of activation of mutated CXCR4.

Introduction

WHIM syndrome is characterized by warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, recurrent bacterial infection, and myelokathexis (severe chronic neutropenia with marrow hyperplasia and inappropriate apoptosis of mature myeloid cells in the bone marrow [BM]).1-5 Many but not all cases of WHIM syndrome have been linked to autosomal dominant mutations in CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), all of which cause truncations of the carboxy-terminus of CXCR4. Specific mutations identified in some families with myelokathexis include R334X, S339fs342X, E343X, and G335 X.2,6,7

CXCR4 and its ligand, stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1; also known as CXCL12), play a central role in BM homing and trafficking of hematopoietic progenitor cells, mobilization of lymphocytes, and release of developing neutrophils from bone marrow.1,8-10 Mice lacking CXCR4 demonstrate defective hematopoiesis and cerebellar and cardiovascular development and die perinatally, highlighting the importance of CXCR4 in these organ systems.11 There is 1 report of a cardiac malformation in a patient who may have had WHIM syndrome.12 In vitro studies of WHIM variants of CXCR4 (mutated CXCR4) have provided evidence for increased agonist-dependent signaling by the mutant receptor, suggesting that the clinical manifestations may be due to hyperfunction of these receptors in vivo. In particular, we previously reported that transduction of the R334X WHIM variant into healthy human CD34+ peripheral blood mobilized stem cells (PBSCs) results in enhanced chemotactic and calcium flux responses of the cells to SDF-1, and found that this effect was associated with and presumably caused by a failure of the mutant receptor to down-regulate and internalize, leading to prolongation of activation.13

In the current study we explore the mechanism of myelokathexis in WHIM syndrome using the NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/J mouse (nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency [NOD/SCID] mouse) xenotransplantation model engrafted with healthy human mobilized CD34+ PBSCs that had been transduced with internal ribosome entry site (IRES)–containing bifunctional retrovirus vectors encoding mutated CXCR4 or wild-type (wt) CXCR4 together with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) construct or with vector-encoding GFP construct only. We will demonstrate that expression of mutated CXCR4 does not itself induce apoptosis in transduced myeloid cells differentiated in culture from the transduced PBSCs, but does result in a WHIM-type myelokathexis pattern of the transduced human cells in the in vivo xenotransplantation model (myeloid apoptosis in marrow and decreased release of cells from the marrow to the circulation).

Materials and methods

G-CSF–mobilized CD34+ PBSCs

Following informed consent (NIH Institutional Review Board–approved Protocol 94-I-0073), PBSCs were collected by apheresis from healthy volunteers who were given 5 days of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF; 10 μg/kg/day for 5 days) to mobilize CD34+ stem cells and who were selected with immunomagnetic beads (ISOLEX300i system; Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL). Cells had been preserved in liquid nitrogen after purification until use in the current study.

Cell culture

PBSCs were cultured in X-VIVO10 (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 1% human serum albumin (HSA), recombinant human stem cell factor (rhSCF), thrombopoietin (TPO), flt3 ligand, and interleukin-3 (IL3) at 50 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL, and 20 ng/mL, respectively (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 4 days after thawing; after day 4, the cells were cultured in X-VIVO10 supplemented with 1% HSA, SCF, TPO, flt3 ligand, IL3, human IL6, human G-CSF, and human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) at 50 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL, 20 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL, and 50 ng/mL, respectively (R&D Systems).

Plasmids

GFP and P144K murine mutant homolog of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (mMGMT*) fusion protein14 gene with IRES were inserted into NcoI-BamHI cloning sites of pMFGS with a chicken β-actin promoter associated with cytomegalovirus immediate-early enhancer (CAG enhancer), a Moloney murine leukemia virus replication–incompetent vector (Cell Genesys, Foster City, CA).15 The cDNA human wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4 gene was inserted into the NcoI-NotI cloning site of pMFGS-IRES-GFPmMGMT* (which itself without either of the CXCR4 constructs was used as a vector control). In our previous study we used similar vectors but observed very low expression of the GFP construct downstream of the IRES element in the bicistronic vector. The addition of the CAG enhancer to the retrovirus vector significantly enhanced both expression of the CXCR4 amounts per cell and the GFP construct expression. We found this to be important in conducting the in vivo studies we describe in this report.

Retrovirus vector production

FLYRD18-packaging cells16 producing RD114 envelope–pseudotyped17-19 MFGS-wt-CXCR4-IRES-GFPmMGMT*, MFGS-mutated-CXCR4-IRES-GFPmMGMT* (mutated CXCR4), or MFGS-GFPmMGMT* (GFP only) vectors (RD114-MFGS vectors) were generated by transduction with vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G)–pseudotyped vectors, which were produced by 293T cells cotransfected with the vector plasmids, a plasmid encoding retrovirus gag-pol, and a plasmid encoding the VSV-G envelope as previously described.13,20 Filtered vector supernatant was collected from confluent FLYRD18 producer cultures. After concentration of the vector by centrifugation (18 600g for 3 hours at 4°C), RD114-MFGS vectors were applied for transduction.

Transduction of PBSCs from healthy humans

PBSCs from healthy human were transduced with RD114-MFGS vectors (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 5-15) overnight 3 times (days 1, 2, and 3) in culture medium containing 6 μg/mL protamine in 6-well plates precoated with RetroNectin (TaKaRa Bio, Otsu, Japan). PBSCs transduced with GFP only served as positive control for GFP expression but as a negative control for expression of wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4 transgenes. Naive nontransduced PBSCs were cultured similarly and served as negative controls for GFP expression.

Migration assay

Transduced or naive nontransduced PBSCs (5 × 105) were loaded into the upper chamber containing 100 μL X-VIVO 10 with 1% HSA, and were allowed to migrate to the lower chamber containing varied concentrations of SDF-1 (PeproTech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ) in a 24-well transwell apparatus (Costar, Corning, NY; pore size 5 μm) at 37°C for 30 minutes. Number of migrated cells was scored visually by light microscopy.

Calcium flux assay

The change of intracellular free calcium concentration induced by activation of CXCR4 in response to SDF-1 was investigated with transduced and naive nontransduced PBSCs using FLIPR calcium flux 3 assays (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Fluorescence measurements were carried out in the FLEXstation (Molecular Devices), and relative fluorescence change (RFC) was calculated by subtraction of the baseline (medium) from the SDF-1 signal. Data analyses were performed with SoftMax Pro software (Molecular Devices).

Colony-forming unit assay

Transduced or naive nontransduced PBSCs at 1 × 103 cells/mL were cultured in duplicate in 1% methylcellulose and Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) supplemented with 30% fetal bovine serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 ng/mL rhSCF, 20 ng/mL rhGM-CSF, 20 ng/mL rhIL3, 20 ng/mL rhIL6, 20 ng/mL rhG-CSF (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, ON, Canada). All colonies were of myeloid phenotype and most were mixed monocytes/granuloctyes in type, but were not further distinguished when counting colonies. For each experiment at least 80 colonies were scored, and the cultures were scored at 14 days in a blinded manner by inverted fluorescence microscopy as described previously.14

Flow cytometry

Phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) was used to detect human CD34 antigen, and allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated mAb was used to detect human CD45 antigen on the cell surface. Anti–human CXCR4–conjugated PECy5 mAb (12G5) was used to detect native, wild-transgene, and mutant-transgene CXCR4 expression. Human CD16 antigen (human neutrophil–specific) was detected by the mouse monoclonal antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Data analysis was performed with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Transplantation into mice

NOD/SCID mice (8 to 12 weeks old) were irradiated with 300 cGy total-body irradiation (139Cs gamma ray) at 2 days before transplantation. Three million transduced or naive nontransduced PBSCs were cultured for 4 days and transplanted into each mouse after intraperitoneal injection of the anti–murine IL2 receptor beta rat mAb (1 mg).21-23

Human cell engraftment

The analysis of human cells in mouse BM and mouse PB was performed at 6 weeks after transplantation by flow cytometry (FACSort; BD Immunocytometry System, San Jose, CA) using anti-CD45–APC mAb. Mice injected with nontransduced cells and cells transduced with GFP only were used as negative controls for retrovirus-mediated CXCR4, and noninjected mice were used as negative controls.

Apoptosis analysis

Apoptotic cells were detected by flow cytometry (FACSort) using annexin V–PE and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD) (BD Biosciences). BM cells harvested from mouse bone were stained with anti–human CD45–APC mAb and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) before apoptosis analysis. Data analysis was performed with CellQuest software.

Quantitative TaqMan PCR

The copy number of the GFP transgene in genomic DNA isolated from BM or ex vivo–cultured human cells was determined by real-time TaqMan polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using a multiplex method that allowed for the amplification of both the GFP transgene and the phenol sulfotransferase (STP) as a human housekeeping gene in the same well. The sequence of primers and probe for GFP gene are as follows: forward primer, 5′-CTTCTTCAAGTCCGCCATGC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CAGGGTGTCGCCCTCGA-3′; and probe, 5′-FAM-TTCTTCAAGGACGACGGCAACTACAAGACCC-TAMRA-3′. The sequence of primers and probe for STP gene are as follows: forward primer, 5′-GGTGCCCTTCCTTGAGTTCA-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CCCCTTGCACCCAGGAC-3′; and probe, 5′-VIC-CCCCAGGGATTCCCTCAGGTGTGT-TAMRA-3′. TaqMan PCR conditions were 50°C for 2 minutes and 95°C for 10 minutes for 40 cycles, 95°C for 15 seconds, and 60°C for 60 seconds. Standard curves used a GFP single-copy clone of transduced K562 cells.

Statistics

Results of experimental points are reported as means plus or minus SD. Significance levels were determined by Student t test for differences in means.

Results

Transduction efficiency and transgene expression

Four days after transduction of PBSCs, the percentage of cells expressing CD34 antigen was 95.8%, 93.3%, and 94.1% for GFP-only, wt CXCR4, or mutated CXCR4 transduction groups, respectively, and 95.7% for naive nontransduced cells. Since all the vectors contained a GFP construct, either alone or together with the CXCR4 sequence, it was possible to assess the percentage of cells expressing GFP fluorescence for each of the transduced groups (75.1%, 71.8%, and 66.5%, respectively, for GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 groups), as well as the percentage of cells binding anti-CXCR4–PECy5 to a level above that of antibody isotype control (12.7%, 69.6%, and 64.3% in the same transduced groups, respectively, and 10.4% for naive, similarly cultured, nontransduced PBSCs).

Effect of transduction of wt and mutated CXCR4 on migration and calcium flux by PBSCs

We have previously reported differences in migration and calcium flux in cells transduced to express excess wt or mutated CXCR4. However, for these in vivo studies we have constructed new vectors that express both CXCR4 (wt or mutated) and GFP from the same vector and achieve higher expression because of the including of a CAG enhancer. We felt that it was essential to reperform these migration and calcium flux function studies to re-establish the functionality and effect of these higher levels of the transgenes derived from the new vectors. The SDF-1–mediated migration assay was performed on day 4 of culture (1 day following the last transduction, which also corresponded to the day the bulk of the cells were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice) with the 3 groups of transduced PBSCs (GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4) and naive nontransduced PBSCs. We evaluated the number of cells migrating in response to 0.5, 1, 5, and 10 nM SDF-1 at 30 minutes of migration, and showed the data in Figure 1A as the percentage of cells in the upper chamber that migrated to the lower chamber for each of these groups. For example, with the raw numerical data observed with 10 nM SDF-1 as the stimulus in the lower chamber, we observed that of the 5.0 × 105 cultured cells loaded onto the upper chamber, the numbers of cells migrating into the lower chamber were 0.97 ± 0.33 × 104 cells, 5.10 ± 0.82 × 104 cells, and 9.45 ± 1.68 × 104 cells for GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 transduced PBSCs, respectively, and 0.81 ± 0.24 × 104 cells for naive nontransduced PBSCs. A statistically significant difference of migration response was observed when comparing the wt CXCR4 transduced group to the mutated CXCR4 transduced group at all concentrations of SDF-1, while both of these 2 groups also demonstrated statistically higher efficacy of migration when compared with either the naive nontransduced or GFP-only transduced groups (Figure 1A; n = 8, P < .01).

WHIM mutation of CXCR4 enhances chemotactic and calcium flux responses to SDF-1 in PBSCs ex vivo. Transduced and naive nontransduced PBSCs were stimulated with SDF-1 at day 4 of ex vivo culture in a migration (A) or calcium-flux (B) assay. Transduced groups expressed GFP-only (♦), or GFP plus either mutated CXCR4 (▪) or wt CXCR4 (•), while naive nontransduced cells did not express any transgenes (▴). (A) Chemotaxis migration assay. Data are the percentage of loaded cells migrating into the lower chamber in response to 0.5, 1, 5, or 10 nM SDF-1 after 30 minutes of stimulation (n = 8, P < .01 for all comparisons between mutated CXCR4 and any of the 3 other groups, or for comparisons between wt CXCR4 and any of the other groups). (B) Calcium flux assay. Data are the peak of relative fluorescence change (RFC) from the baseline within 30 seconds of stimulation (n = 6, P < .01 for all comparisons between mutated CXCR4 and any of the 3 other groups, or between wt CXCR4 and any of the other groups).

WHIM mutation of CXCR4 enhances chemotactic and calcium flux responses to SDF-1 in PBSCs ex vivo. Transduced and naive nontransduced PBSCs were stimulated with SDF-1 at day 4 of ex vivo culture in a migration (A) or calcium-flux (B) assay. Transduced groups expressed GFP-only (♦), or GFP plus either mutated CXCR4 (▪) or wt CXCR4 (•), while naive nontransduced cells did not express any transgenes (▴). (A) Chemotaxis migration assay. Data are the percentage of loaded cells migrating into the lower chamber in response to 0.5, 1, 5, or 10 nM SDF-1 after 30 minutes of stimulation (n = 8, P < .01 for all comparisons between mutated CXCR4 and any of the 3 other groups, or for comparisons between wt CXCR4 and any of the other groups). (B) Calcium flux assay. Data are the peak of relative fluorescence change (RFC) from the baseline within 30 seconds of stimulation (n = 6, P < .01 for all comparisons between mutated CXCR4 and any of the 3 other groups, or between wt CXCR4 and any of the other groups).

With the same transduced PBSCs we investigated calcium flux induced by activation of the CXCR4 receptor in response to different concentrations of SDF-1. At 10 nM SDF-1, the stimulated calcium flux assay peak of RFC (in relative fluorescence units) observed within 30 seconds of stimulation were 14 645 ± 2109, 29 943 ± 4037, and 45 820 ± 3447 for the GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 transduced PBSCs, respectively, and 12 594 ± 5053 for naive nontransduced PBSCs. As with the migration assay, the RFC peak in response to serial concentrations of SDF-1 were significantly higher with the mutated CXCR4 transduced group compared with the wt CXCR4 transduced group, while both of these 2 groups also demonstrated statistically higher efficacy of calcium flux when compared with either the naive nontransduced or GFP-only transduced groups (Figure 1B; n = 6, P < .01). As expected, naive nontransduced PBSC migration and calcium flux responses to SDF-1 were indistinguishable from the responses of GFP-only transduced PBSCs, indicating no toxicity of the transduction process or expression of GFP. Furthermore, GFP-only transduced cells and naive nontransduced cells had no difference in the expression of native CXCR4.

Colony-forming assays and GFP expression in colonies

CFU assays were performed at day 4 of culture with GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 transduced PBSCs and nontransduced PBSCs. At 14 days after culturing in semisolid medium, the total number of colonies per 1 × 103 cells plated were 107 ± 18, 103 ± 15, and 99 ± 18, respectively, and 114 ± 14 for the naive nontransduced group. These colonies demonstrated 35.4% ± 4.2%, 32.4% ± 4.6%, 30.9% ± 4.6%, and 0% GFP+ colonies, respectively. For the 3 transduced groups, there was no difference in the percentage of GFP+ colonies (4 individual experiments), nor were there differences in the number of total colonies. This confirms that transduction levels were similar in the 3 transduced groups, but also that neither transduction itself nor the expression of GFP affected the colony number.

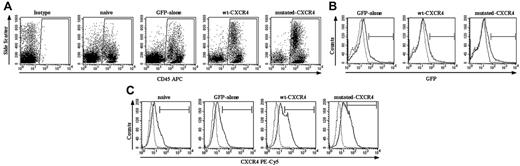

Effect of excess expression of wt or mutated CXCR4 transgene on engraftment of human PBSCs in the NOD/SCID xenograft model

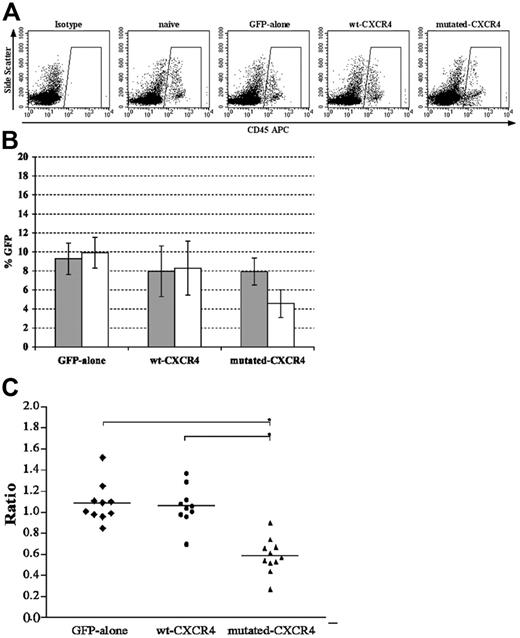

We next examined human cells engrafted in the BM and circulating in the PB after transplantation of the different groups of human PBSCs into NOD/SCID mice. At 6 weeks, the BM of mice given transplants of the GFP-only wt CXCR4 and mutated CXCR4 transduced human PBSC groups or naive human cells demonstrated that 33.7% ± 6.1%, 53.5% ± 5.7%, 68.5% ± 13.4%, and 38.2% ± 5.7% of cells were human CD45+ leukocytes, respectively, for each of the 4 groups (Figure 2A;P < .001 for wt or mutated CXCR4 versus GFP or naive; P < .001 for mutated versus wt). The apparent number of human cells expressing GFP above the naive cell control baseline was 9.3% ± 1.7%, 8.0% ± 2.7%, 7.9% ± 1.4%, and 0.3% ± 0.1% (for the naive PBSC group the background GFP by definition was set at 0.3% in 1 of the mice), respectively (Figure 2B and the gray bars in Figure 3B). These same groups of CD45+ human cells in the mouse BM demonstrated anti-CXCR4–PECy5 binding above isotype antibody control in 15.8% ± 3.7%, 29.5% ± 6.1%, 28.2% ± 6.0%, and 14.8% ± 5.0% of the human cells, respectively. Thus, there was significantly enhanced expression of CXCR4 in both wt CXCR4 and mutated CXCR4 groups compared with naive nontransduced and GFP-only groups (n = 10, P < .01; Figure 2C). The percentage of CD45+ human cells in the PB of these same groups of mice that received transplants were 2.4% ± 1.3%, 2.1% ± 0.9%, 2.5% ± 1.4%, and 2.7% ± 1.6%, respectively (Figure 3A), where the percentage of human cells in the PB observed to express GFP above background was 9.9% ± 1.6%, 8.3% ± 2.8%, 4.6% ± 1.5%, and 0.2% ± 0.1%, respectively (Figure 3B). We wanted to know if excess expression of wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4 affected release of transduced CD45+ leukocytes from the BM to the circulating PB. There could be some cells that express transgene, while the level of GFP expression remains lower than gating for GFP positivity. However, we postulated that if we focused on analysis of only those cells that were clearly GFP+, we could more clearly assess the effect of expression of excess wt or mutated CXCR4. We did this by calculating the following ratios shown in Figure 3C: (% GFP+ human CD45+ cells circulating in PB)/(% GFP+ human CD45+ cells engrafted in BM).

WHIM mutation of CXCR4 enhances engraftment of PBSCs in NOD/SCID mice. BM of NOD/SCID mice that received transplants of naive nontransduced PBSCs, PBSCs transduced with GFP only, or GFP plus either wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4 were analyzed at 6 weeks by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) for the markers indicated on the x-axes. (A) After harvest from mice BM, cells were stained with anti–human CD45–APC or isotype antibody. Shown is a representative analysis from 1 mouse in each group, where the numerical averages for the groups are provided in the text. Enhanced human cell engraftment was observed in both mutated CXCR4 and wt CXCR4 groups compared with naive and GFP-only groups (n = 10, P < .01; see “Effect of excess expression of wt or mutated CXCR4 transgene on engraftment of human PBSCs in the NOD/SCID xenograft model for group values). (B) Shown is a representative set of graphs showing GFP expression in the gated population of human CD45+ leukocytes as the black solid line in each panel as labeled, with background fluorescence seen in the naive nontransduced group shown as the dotted line in each panel. There is no significant difference between the groups. It is important to note that these curves suggest that there probably are a significant number of weakly GFP+ transduced cells that are not counted when a gate is simply set to the 99.7 percentile of the naive control. The group numbers of percentage of GFP+ cells exceeding the 99.7 percentile for the naive group are given in the text under “Effect of excess expression of wt or mutated CXCR4 transgene on engraftment of human PBSCs in the NOD/SCID xenograft model.” (C) Shown is a representative set of graphs indicating the CXCR4 expression in the gated population of human CD45+ leukocytes as the black solid line in each panel as labeled, with the background level of fluorescence seen with labeling with isotype control antibody indicated by the dotted line. Note that there is as expected a significant amount of expression of native CXCR4 in the naive and GFP-only transduced populations of human CD45+ leukocytes from the BM xenograft. There is a highly significant amount of extra expression of transgene-derived wt CXCR4 and mutated CXCR4 in those transduced populations (n = 10, P < .01 for either the wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4 groups compared with the naive or GFP-only groups). Note that it is difficult to accurately assess the actual number of cells expressing the CXCR4 transgene over background native CXCR4. Here again, it is important to note that these curves suggest that there probably are a significant number of weakly CXCR4+ cells that are not counted when a gate is simply set to the 99.7 percentile of the antibody isotype control. The group numbers of percentages of CXCR4+ cells exceeding the 99.7 percentile for the naive group are given in the text under “Effect of excess expression of wt or mutated CXCR4 transgene on engraftment of human PBSCs in the NOD/SCID xenograft model.”

WHIM mutation of CXCR4 enhances engraftment of PBSCs in NOD/SCID mice. BM of NOD/SCID mice that received transplants of naive nontransduced PBSCs, PBSCs transduced with GFP only, or GFP plus either wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4 were analyzed at 6 weeks by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) for the markers indicated on the x-axes. (A) After harvest from mice BM, cells were stained with anti–human CD45–APC or isotype antibody. Shown is a representative analysis from 1 mouse in each group, where the numerical averages for the groups are provided in the text. Enhanced human cell engraftment was observed in both mutated CXCR4 and wt CXCR4 groups compared with naive and GFP-only groups (n = 10, P < .01; see “Effect of excess expression of wt or mutated CXCR4 transgene on engraftment of human PBSCs in the NOD/SCID xenograft model for group values). (B) Shown is a representative set of graphs showing GFP expression in the gated population of human CD45+ leukocytes as the black solid line in each panel as labeled, with background fluorescence seen in the naive nontransduced group shown as the dotted line in each panel. There is no significant difference between the groups. It is important to note that these curves suggest that there probably are a significant number of weakly GFP+ transduced cells that are not counted when a gate is simply set to the 99.7 percentile of the naive control. The group numbers of percentage of GFP+ cells exceeding the 99.7 percentile for the naive group are given in the text under “Effect of excess expression of wt or mutated CXCR4 transgene on engraftment of human PBSCs in the NOD/SCID xenograft model.” (C) Shown is a representative set of graphs indicating the CXCR4 expression in the gated population of human CD45+ leukocytes as the black solid line in each panel as labeled, with the background level of fluorescence seen with labeling with isotype control antibody indicated by the dotted line. Note that there is as expected a significant amount of expression of native CXCR4 in the naive and GFP-only transduced populations of human CD45+ leukocytes from the BM xenograft. There is a highly significant amount of extra expression of transgene-derived wt CXCR4 and mutated CXCR4 in those transduced populations (n = 10, P < .01 for either the wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4 groups compared with the naive or GFP-only groups). Note that it is difficult to accurately assess the actual number of cells expressing the CXCR4 transgene over background native CXCR4. Here again, it is important to note that these curves suggest that there probably are a significant number of weakly CXCR4+ cells that are not counted when a gate is simply set to the 99.7 percentile of the antibody isotype control. The group numbers of percentages of CXCR4+ cells exceeding the 99.7 percentile for the naive group are given in the text under “Effect of excess expression of wt or mutated CXCR4 transgene on engraftment of human PBSCs in the NOD/SCID xenograft model.”

WHIM mutation of CXCR4 skews distribution of transduced human PBSCs after transplantation in NOD/SCID mice. Flow cytometry analysis was performed to measure GFP expression by the human CD45+ gated population from paired samples of bone marrow and peripheral blood from each mouse that received xenografts in each transplantation group. (A) After harvest from mice PB, cells were stained with anti–human CD45–APC or isotype antibody. Shown is a representative analysis from 1 mouse in each group where the numeric averages for the groups are provided in the text. There is no difference in the percentages of human CD45+ cells in all groups. (B) Average ± standard deviation (error bars) for GFP expression by engrafted human cells for each group for BM (⊡) or PB (□). Note that only with the mutated CXCR4 was the value for PB significantly lower than that for BM (P < .01). (C) Ratio of the value for PB/BM for each individual mouse in the group so that the actual raw data over the group can be assessed. The line shows the average for the group and is the same value as that of each □ divided by ⊡ in panel B. The lowest ratio was observed in the mutated CXCR4 group (n = 10 for GFP-only and wt CXCR4 groups, and n = 11 for mutated-CXCR4 group; *P < .01 for the comparisons shown in panel C).

WHIM mutation of CXCR4 skews distribution of transduced human PBSCs after transplantation in NOD/SCID mice. Flow cytometry analysis was performed to measure GFP expression by the human CD45+ gated population from paired samples of bone marrow and peripheral blood from each mouse that received xenografts in each transplantation group. (A) After harvest from mice PB, cells were stained with anti–human CD45–APC or isotype antibody. Shown is a representative analysis from 1 mouse in each group where the numeric averages for the groups are provided in the text. There is no difference in the percentages of human CD45+ cells in all groups. (B) Average ± standard deviation (error bars) for GFP expression by engrafted human cells for each group for BM (⊡) or PB (□). Note that only with the mutated CXCR4 was the value for PB significantly lower than that for BM (P < .01). (C) Ratio of the value for PB/BM for each individual mouse in the group so that the actual raw data over the group can be assessed. The line shows the average for the group and is the same value as that of each □ divided by ⊡ in panel B. The lowest ratio was observed in the mutated CXCR4 group (n = 10 for GFP-only and wt CXCR4 groups, and n = 11 for mutated-CXCR4 group; *P < .01 for the comparisons shown in panel C).

With this transformation of the data regarding presence of GFP+ human cells in the 2 hematopoietic compartments of each NOD/SCID mouse, it can be noted that the ratio is lowest for the mutated CXCR4 group (0.58 ± 0.13), which is almost half the ratio of the wt CXCR4 and GFP-only groups (1.06 ± 0.18 and 1.08 ± 0.20, respectively). This suggests a very significant effect of the expression of mutated CXCR4 on the release of mature leukocytes from the BM to the PB (n = 10 for GFP-only and wt CXCR4 groups; n = 11 for the mutated CXCR4 group; *P < 0.01). Surprisingly, this is an effect that appears to be specific to the mutated CXCR4 group and apparently not caused just by excess expression of the normal wt CXCR4 transgene.

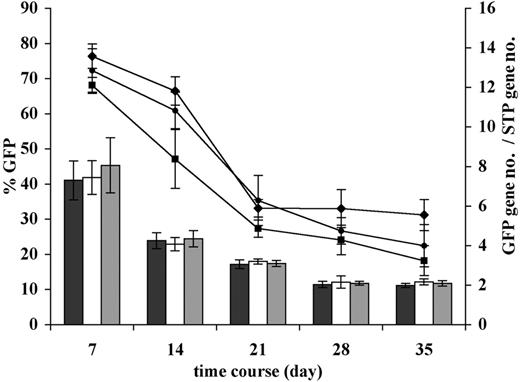

Copy number of transgene in transduced cells

We also performed quantitative TaqMan PCR analysis to determine the copy number of the GFP insert in the ex vivo transduced human PBSCs in culture and in the BM of the mice 6 weeks after transplantation. For both analyses we used a multiplexed analysis whereby the copy number of the human housekeeping gene, STP, was used to normalize the data to the amount of human DNA in the sample. Figure 4 shows the changes in GFP marking compared with the average copy number over time in ex vivo culture for the GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 groups. The data demonstrates that in all 3 groups both GFP expression and copy number decrease significantly in parallel but stabilize after about 21 days in culture, such that there is only a modest drop in actual copy number per GFP+ cell in the culture. The apparent final copy numbers per GFP+ cell at 35 days of culture were 6.3, 9.6, and 11.5 for the GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 groups, respectively. Mean GFP fluorescence intensity of these groups at 35 days was 143.4, 105.0, and 84.3, respectively. This apparent difference in copy number per GFP cell in the GFP-only group in part likely reflects the higher average green fluorescence intensity per cell in this group where there is no competition for production of 2 transgenes as there is in the bicistronic CXCR4-IRES-GFP vectors. Thus, there are likely cells containing either of the CXCR4-IRES-GFP vectors that make amounts of GFP too small to be within the gating for GFP+ cells. When we measured the apparent GFP copy number in human DNA in the total xenograft BM samples, the copy number of GFP transgene per human cell in the sample (normalized for human DNA using the STP housekeeping human gene) appeared to be 0.55, 0.85, and 1.03 for GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 groups, respectively (n = 6, P < .01 for mutated CXCR4 versus GFP only, and P = .02 for wt CXCR4 versus GFP only; the trend toward higher copy numbers in the mutated CXCR4 versus wt CXCR4 did not reach statistical significance). Of note is that when this was normalized to the percentage of human cells that were GFP+ by flow cytometry, the average copy number per GFP+ cell was 6.0, 10.7, and 13.0, which is very similar to the 6.3, 9.6, and 11.5 seen in the long-term cultures.

Change in percentage of GFP and GFP transgene insert copy number during prolonged ex vivo culture of transduced human PBSCs. Following transduction of human CD34+ PBSCs with the vectors encoding GFP only, or GFP plus either wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4, most cells were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice; for some experiments (n = 4), cells were retained in long-term ex vivo culture. Long-term culture conditions consisted of X-VIVO10 culture medium containing 50 ng/mL hSCF, hTPO, and hFLT3-ligand, and 20 ng/mL hIL3, IL6, G-CSF, and GM-CSF. FACS analysis of GFP expression (lines) or quantitative real-time PCR–based assessment of GFP sequence copy number (bars) was performed at the culture days indicated on the horizontal axis. Percentages of GFP+ cells started out at similar high level and decreased in a parallel fashion for all the groups to about half the value by day 35, consistent with a higher level of transduction of short-term progenitors than transduction of longer-term progenitors (GFP only, ♦; wt CXCR4, •; and mutated CXCR4, ▪). The total GFP copy number per cell for each group is shown to also start out very high and to decrease in parallel more than 3-fold for each of the groups (GFP only, ▪; wt CXCR4, □; and mutated CXCR4, ⊡). The data suggest that as assessed in the long-term culture ex vivo environment, the transduction rates of long-term progenitors are similar in the 3 transduction groups. It is possible that high expression of wt and mutated CXCR4 in short-term progenitors early in culture at the time of transplantation into mice may enhance final long-term engraftment through some “helper” function, even when eventually a much lower percentage of long-term progenitors continues to express transgene.

Change in percentage of GFP and GFP transgene insert copy number during prolonged ex vivo culture of transduced human PBSCs. Following transduction of human CD34+ PBSCs with the vectors encoding GFP only, or GFP plus either wt CXCR4 or mutated CXCR4, most cells were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice; for some experiments (n = 4), cells were retained in long-term ex vivo culture. Long-term culture conditions consisted of X-VIVO10 culture medium containing 50 ng/mL hSCF, hTPO, and hFLT3-ligand, and 20 ng/mL hIL3, IL6, G-CSF, and GM-CSF. FACS analysis of GFP expression (lines) or quantitative real-time PCR–based assessment of GFP sequence copy number (bars) was performed at the culture days indicated on the horizontal axis. Percentages of GFP+ cells started out at similar high level and decreased in a parallel fashion for all the groups to about half the value by day 35, consistent with a higher level of transduction of short-term progenitors than transduction of longer-term progenitors (GFP only, ♦; wt CXCR4, •; and mutated CXCR4, ▪). The total GFP copy number per cell for each group is shown to also start out very high and to decrease in parallel more than 3-fold for each of the groups (GFP only, ▪; wt CXCR4, □; and mutated CXCR4, ⊡). The data suggest that as assessed in the long-term culture ex vivo environment, the transduction rates of long-term progenitors are similar in the 3 transduction groups. It is possible that high expression of wt and mutated CXCR4 in short-term progenitors early in culture at the time of transplantation into mice may enhance final long-term engraftment through some “helper” function, even when eventually a much lower percentage of long-term progenitors continues to express transgene.

Assessment of rates of apoptosis in transduced human cells in culture and human cells engrafted in the NOD/SCID mouse

We next assessed rates of apoptosis of the CD45+ human cells engrafted in the BM of these NOD/SCID mice that received transplants. When focusing on GFP− cells, no difference in rates of apoptosis were observed, indicating that there was no generalized environmental factor in the marrow inducing apoptosis in human cells engrafted in the NOD/SCID mice. However, when focusing on rates of apoptosis in only the GFP-expressing CD45+ cells it was observed that apoptotic rates were 11.6% ± 3.8%, 11.2% ± 4.2%, and 19.8% ± 3.5% in the GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 groups, respectively. Thus, there is a highly significant increase in apoptosis rate observed in the CD45+GFP+ cells in BM from the mutated CXCR4 transduced group of mice relative to the other groups (Figure 5; n = 7 for mutated CXCR4, n = 5 for wt CXCR4 and GFP-only, P < .01).

However, when we assessed rates of apoptosis in the transduced and naive cultured cells in the ex vivo culture either before transplantation or after prolonged culture allowing differentiation into myeloid cells, we did not find any difference in apoptotic rates. In order to know whether cells expressing wt or mutated CXCR4 at the highest levels very early after transduction (day 4 from initiation of culture; end of last transduction) had higher rates of apoptosis, we gated specifically on the cells with very high GFP expression (above an MFI of 6 × 102 where the cutoff between GFP+ and GFP− was at 3 × 101) and found apoptosis rates in this population to be 4.5% ± 0.8%, 4.2% ± 0.6%, and 4.7% ± 0.5% for GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 groups, respectively. Thus, high expression of either CXCR4 transgene did not affect apoptotic rates at the earliest time point. Even at day 11 of culture (day 7 after the last transduction), the percentage of all GFP+ apoptotic cells in the annexin V assay were 9.3% ± 3.7%, 8.6% ± 2.8%, and 9.1% ± 2.1%, respectively, for GFP-only, wt CXCR4, and mutated CXCR4 groups. GFP− cells from these groups demonstrated apoptosis rates of 8.8% ± 2.7%, 8.9% ± 2.6%, and 8.2% ± 2.7%, respectively, and 7.9% ± 2.0% for naive nontransduced cells. None of these differed statistically from the rest. The data were similar at 21 and 28 days of culture. Specifically, at 21 days of culture the apoptotic rates were 9.1% ± 2.7%, 10.4% ± 3.0%, and 10.9% ± 3.0%, respectively, for all cells and did not differ at all from these numbers when gating only on CD16 cells (neutrophils), which represented about 40% of live cells in the day-22 culture. Moreover, when cells were exposed to SDF-1 at a concentration of 5 nM for 24 hours, the apoptosis rate did not change. Thus, the enhanced apoptosis of human cells expressing mutated CXCR4 appears to be a phenomenon seen in in vivo but not ex vivo culture, and cannot be explained simply as an abnormal stimulation of apoptosis in response to SDF-1.

WHIM mutation of CXCR4 increases apoptosis of transduced human CD45+ cells in the BM of NOD/SCID mice at 6 weeks after transplantation. BM of mice that received transplants of GFP-only cells, or GFP plus either wt CXCR4– or mutated CXCR4–transduced cells, and naive nontransduced human CD34+ cells were evaluated at 6 weeks. The BM containing both GFP+ and GFP− cells was stained with anti-CD45–APC (to allow gating on only human leukocytes), annexin V–PE (as a measure of the membrane lipid changes characteristic of apoptosis), and 7AAD (to exclude dead cells), and analyzed using dual-laser 4-color flow cytometry. Shown in the bar graph for each group are either the GFP− (□) or GFP+ (⊡) annexin V+ live human leukocytes. There was no statistical difference in rates of in vivo apoptosis between any of the groups except for the GFP+ mutated CXCR4–transduced group, which was statistically higher than all other groups (n = 5 for naive, GFP-only, and wt CXCR4 groups, and n = 7 for mutated CXCR4; *P < .01 for all comparisons). The slight trend to higher apoptosis rates in the GFP− mutated CXCR4 group compared with the other GFP− cell groups may be due to the fact that the GFP expression from the mutated CXCR4-IRES-GFP construct may be so low in some transduced cells that they contribute to overall slightly higher apoptosis in the supposedly GFP− population.

WHIM mutation of CXCR4 increases apoptosis of transduced human CD45+ cells in the BM of NOD/SCID mice at 6 weeks after transplantation. BM of mice that received transplants of GFP-only cells, or GFP plus either wt CXCR4– or mutated CXCR4–transduced cells, and naive nontransduced human CD34+ cells were evaluated at 6 weeks. The BM containing both GFP+ and GFP− cells was stained with anti-CD45–APC (to allow gating on only human leukocytes), annexin V–PE (as a measure of the membrane lipid changes characteristic of apoptosis), and 7AAD (to exclude dead cells), and analyzed using dual-laser 4-color flow cytometry. Shown in the bar graph for each group are either the GFP− (□) or GFP+ (⊡) annexin V+ live human leukocytes. There was no statistical difference in rates of in vivo apoptosis between any of the groups except for the GFP+ mutated CXCR4–transduced group, which was statistically higher than all other groups (n = 5 for naive, GFP-only, and wt CXCR4 groups, and n = 7 for mutated CXCR4; *P < .01 for all comparisons). The slight trend to higher apoptosis rates in the GFP− mutated CXCR4 group compared with the other GFP− cell groups may be due to the fact that the GFP expression from the mutated CXCR4-IRES-GFP construct may be so low in some transduced cells that they contribute to overall slightly higher apoptosis in the supposedly GFP− population.

Discussion

G-CSF–mobilized PBSCs from healthy humans that were transduced to express either mutated CXCR4 or excess wt CXCR4 demonstrated enhanced migration and calcium flux in response to SDF-1 compared with PBSCs transduced with the GFP-only construct to express only the GFP transgene. Furthermore, expression of mutated CXCR4 transgene induced a demonstrably greater effect on migration or calcium flux function than expression of excess wt CXCR4. It is of note that despite the fact that overexpression of wt CXCR4 over the baseline of native CXCR4 could enhance migration and calcium flux in response to SDF-1, only expression of mutated CXCR4 resulted in excessive in vivo apoptosis rates in the human leukocytes in the xenograft and a highly significant reduction in release of marked human leukocytes from BM into the PB. Thus, the mechanism by which expression of mutated CXCR4 affected in vivo apoptosis and release of cells to the PB from the BM was not reproduced simply by excess expression of the wt CXCR4 transgene, despite the fact that both are capable of enhancing migration and calcium flux responses to SDF-1 in culture.

However, there was no evidence at all of increased apoptosis of human cells in culture that expressed the mutated CXCR4, even after prolonged culture at a time when mature myeloid cells were being produced; nor was this changed by exposure to SDF-1 in the culture. This suggests that expression and activation of mutated CXCR4 is not itself a trigger for apoptosis whether at rest or in response to SDF-1 stimulation. It is most likely that the increased apoptosis (myelokathexis) of myeloid cells seen in the BM of patients with WHIM who had the associated neutropenia results from the retention of postmature leukocytes in the BM, where they progress into the normal apoptotic cycle that usually does not occur until a few days after release from the marrow.

This hypothesis has clinical implications in that any therapeutic maneuver that enhances release of neutrophils from the BM is likely to decrease the apparent apoptotic rate in the marrow and result in the release of neutrophils into the circulation, which are likely at that point to have a relatively normal lifespan before apoptosis. In fact, a recent study has suggested that G-CSF not only enhances marrow production of myeloid cells, but that it has a profound effect on the down-regulation of CXCR4 as a mechanism for mobilization of myeloid cells from the BM.24,25 G-CSF treatment is a commonly used and reasonably effective way to correct the neutropenia of WHIM syndrome and reduce recurrent infections.6,26,27 Our studies provide a mechanism and rationale for this treatment. Since a specific small-molecule inhibitor of CXCR4 is in clinical trial for mobilization of stem cells,28-30 it is likely that this agent also would be efficacious in WHIM syndrome to mobilize the neutrophils that are abnormally retained in the BM.

Previous studies by several investigators and our own group have demonstrated that excess expression of wt CXCR4 transgene in hematopoietic stem cells can enhance engraftment in BM.31,32 We show for the first time that expression of mutated CXCR4 can enhance engraftment of human stem cells into the NOD/SCID xenograft model with even greater efficacy than excess expression of wt CXCR4. This strongly supports the notion that methods to enhance the expression of native CXCR4 by stem cells before transplantation might enhance engraftment, but also raises the possibility that transient expression systems used to express the C-terminal–truncated form of CXCR4 might have therapeutic utility to enhance establishment of a graft. Clearly, such a concept would require much development and safety testing before any consideration for clinical application, but it is a concept worth exploration.

It is of note that in a mouse model, inhibition of natural cleavage of SDF-1 by a CD26 (DPPIV [dipeptidylpeptidase IV]) peptidase inhibitor33,34 enhances marrow in in situ stimulation of CXCR4, resulting in enhanced engraftment. Although this inhibitor does not appear to act on any known equivalent peptidase in human progenitor cells,35 it is possible that an equivalent peptidase may be identified allowing development of a similar inhibitor. It is possible that synergy could be achieved by combining such an inhibitor with the transient expression of mutated CXCR4 to achieve greatly enhanced engraftment.

In summary, we use a mouse xenograft model to show for the first time that expression of the WHIM type C-terminal–truncated hyperfunctional mutant CXCR4 in human progenitor cells does not itself mediate enhanced apoptosis, but retards release of leukocytes from the BM, where the postmature cells remain and progress into the normal apoptosis senescence process. It provides a mechanism and rationale for the clinical use of G-CSF or other treatments that block CXCR4 activity and enhances premature release of neutrophils from the marrow to treat patients with WHIM syndrome.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contribution: T.K. and H.L.M. designed the study; T.K., U.C., S.D., N.N., N.W.T., G.F.L., and J.M. performed the research; L.C. provided essential animal handling and care; P.M.M. provided critical plasmid materials and expertise about CXCR4; and T.K. and H.L.M. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Toshiyuki Tanaka and John E. Dick for providing the anti–murine IL2 receptor beta rat monoclonal antibody that reduces NK cell activity in the NOD/SCID mouse, thereby enhancing engraftment of human PBSCs in our model system. We dedicate this manuscript to the memory of Joan Sechler.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal