Abstract

Myeloproliferation, myelofibrosis, and neoangiogenesis are the 3 major intrinsic pathophysiologic features of myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis (MMM). The myeloproliferation is characterized by an increased number of circulating CD34+ progenitors with the prominent amplification of dystrophic megakaryocytic (MK) cells and myeloid metaplasia in the spleen and liver. The various biologic activities of interleukin 8 (IL-8) in hematopoietic progenitor proliferation and mobilization as well as in neoangiogenesis prompted us to analyze its potential role in MMM. We showed that the level of IL-8 chemokine is significantly increased in the serum of patients and that various hematopoietic cells, including platelets, participate in its production. In vitro inhibition of autocrine IL-8 expressed by CD34+ cells with either a neutralizing or an antisense anti–IL-8 treatment increases the proliferation of MMM CD34+-derived cells and stimulates their MK differentiation. Moreover, addition of neutralizing anti–IL-8 receptor (CXC chemokine receptor 1 [CXCR1] or 2 [CXCR2]) antibodies to MMM CD34+ cells cultured under MK liquid culture conditions increases the proliferation and differentiation of MMM CD41+ MK cells and restores their polyploidization. Our results suggest that IL-8 and its receptors participate in the altered MK growth that features MMM and open new therapeutic prospects for this still incurable disease.

Introduction

Myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis (MMM), a chronic myeloproliferative disorder also called idiopathic myelofibrosis or agnogenic myeloid metaplasia, is a clonal process with a hematopoietic stem cell/progenitor origin. Myeloproliferation with inefficient hematopoiesis and bone marrow fibrosis are the main biologic hallmarks of this rare disease.1,2 Neoangiogenesis is also frequently observed. Cytogenetic and enzymatic studies have demonstrated the clonal nature of the hematopoietic progenitor (HP) expansion and the polyclonality of the neighboring proliferating fibroblasts.3-5 Bone marrow fibrosis is considered a reactive process resulting from the stimulation of nonclonal fibroblasts by growth factors derived from necrotic and dysplastic megakaryocytes.6-8

The myeloproliferative process is characterized by an increased number of HPs9 with a prominent proliferation of the megakaryocytic (MK) cells that exhibited a dysplastic appearance created by their plump lobulation of nuclei and the disturbance of nuclear/cytoplasmic maturation.10 This process is associated with a tremendous CD34+ HP mobilization from the bone marrow (BM) to spleen and liver through to the peripheral blood (PB).11,12 While the underlying molecular genetic alterations remain unknown, recent data led us to propose a model integrating alterations in the expression and function of MK nuclear regulatory factors and in the complex network of humoral and cellular interactions between hematopoietic cells and stroma in the pathogenetic mechanisms of the disease.13,14

Interleukin 8 (IL-8) is a member of the family of chemokines related by a CXC motif. It binds to two 7-transmembrane–domain CXC chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1) and 2 (CXCR2) receptors that belong to the superfamilly of G protein–coupled receptors with high affinity.15-17 CXCR1 also binds to granulocyte chemotactic protein 2 (GCP-2), neutrophil-activating peptide 2 (NAP2), and epithelial neutrophil-activating peptide 78 (ENA-78) with low affinity, 18,19 while CXCR2 responds to additional chemokines such as those of the growth-related oncogene (GRO) family.20,21 IL-8 is produced in vitro by many cell types, including fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, neutrophils, mast cells, monocytes, macrophages, and megakaryocytes, 22-25 and exhibits several biologic activities. IL-8 is a major factor in acute inflammation, acting as a potent chemoattractant and activator of neutrophils by activation of CXCR1 and CXCR2.26-28 IL-8 administration in mice induces a rapid neutrophilia and a concurrent HP mobilization.29-31 Similarly, IL-8 and macrophage inflammatory protein–1α (MIP-1α) can modulate the homing of HPs by affecting the secretion of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) proteases by BM and PB CD34+ cells.32 IL-8 also modulates myelopoiesis by suppressing the myeloid progenitor proliferation.33,34 It is suggested that this suppressive activity is mediated via the expression of CXCR2 receptor on BM-derived HPs.20,35 In contrast to platelet factor 4 (PF4), IL-8 that contains the ELR-CXC chemokine motif induces endothelial chemotaxis and proliferation in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo.36,37

The various biologic activities of IL-8 prompted us to analyze its role in the pathogenesis of MMM, a disease in which myeloproliferation, myelofibrosis, and neoangiogenesis are the major intrinsic pathophysiologic characteristics. In the present study, we showed that the IL-8 level is strongly increased in the serum of patients with MMM and that its expression is partly related to hematopoietic cells including platelets. By using antisense and antibodies against IL-8, we showed its involvement in the myeloproliferative process observed in patients with MMM. Using a similar strategy, we also demonstrated the participation of CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors in the altered MMM MK proliferation, differentiation, and ploidization.

Materials and methods

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

The mAbs directed against CD14 (RM052-phycoerythrin/RM052–fluorescein isothiocyanate [RM052-PE/RM052-FITC]), CD38 (T16-FITC), CD41/glycoprotein IIb (CD41/GPIIb) (P2-FITC), CD42a/GPIX (SZ1-FITC), CD42b/GPIb (SZ2-FITC), CD117/c-kit (95C3-PE), glycophorin A (GPA) (11E4B-7-6–FITC) were obtained from Beckman Coulter-Immunotech (Marseille, France). Mouse antihuman CD15 (Leu-M1-FITC), CD34 8G12–peridinin chlorophyll-alpha protein (8G12-PerCP), CD62P (AK-4–PE), IL-8RA/CXCR1 (5A12-PE), IL-8RB/CXCR2 (6C6-PE), and CD90/thymus cell antigen–1 (Thy1) (5E10-PE) were from Becton Dickinson/Pharmingen (Le Pont de Claix, France); CD41 (5B12 unconjugated or PE) and CD61 (Y2/51-FITC) were from DakoCytomation (Trappes, France). Murine immunoglobulin Gs (IgGs) of the same isotype were used as negative controls. The unconjugated CD41 was revealed with the use of goat anti-mouse–FITC (GAM-FITC) as the secondary antibody (Beckman Coulter-Immunotech). Mouse antihuman CD9 (SYB-1) was a gift from C. Boucheix (Paul Brousse Hospital, Villejuif, France).

Sample collections

Since fibrosis precludes marrow aspiration, samples were obtained from the PB of 37 patients with MMM (age, 65 ± 9 years) not receiving chemotherapy at the time of the study. Diagnosis was established according to the Polycythemia Vera Study Group (PVSG) clinical and hematologic criteria.38 Normal bone marrow (NBM) and peripheral blood (NPB) samples were obtained from 8 healthy individuals undergoing hip prosthesis surgery and from 32 healthy unmobilized subjects, respectively, with their informed consent.

Cell preparations

Mononuclear cells were isolated either from NBM or NPB or from the PB of patients with MMM through Ficoll centrifugation, and CD34+ cells were recovered by the immunomagnetic magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) system (Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France) as previously described.39 This procedure gave rise to more than 98% pure viable CD34+ cells. Washed platelets were obtained as previously described.40

Flow cytometry analysis

Purified CD34+ cells were costained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs directed against the CD34 antigen (8G12-PerCP) and against other antigens to allow flow cytometric analysis using a 4-color FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson) as already described.41 When used, the biotin-labeled mAb was revealed by allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated streptavidin. For IL-8 intracellular detection, whole blood cells and freshly purified CD34+ were incubated for 5 hours with brefeldin A (Golgistop; Becton Dickinson/Pharmingen) (10 μg/mL, 4°C). After being washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 1 × containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), cells were surface stained with CD14-, CD15-, CD41-, CD42b-, GPA-, CD42a-FITC or their isotype controls and subjected to intracellular IL-8 labeling by means of Cytofix/Cytoperm kit and a PE-mouse antihuman IL-8 antibody (Becton Dickinson/Pharmingen). For each sample, 5 × 104 events were acquired, stored in list mode data files, and analyzed with Cellquest (Becton Dickinson) or WinMDI (Joe Trotter; The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) softwares.

IL-8 immunostaining

PB mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (8 × 104) were smeared onto glass slides by cytospin centrifugation and permeabilized with 100% methanol for 20 minutes at 4°C. After being washed, cells were coincubated with anti-CD41–FITC (P2; Beckman Coulter-Immunotech) and anti–IL-8–PE antibodies (G265-8; Pharmingen) for 45 minutes in the dark at room temperature. After being washed, cells were incubated for 30 minutes with a 1:200 dilution of goat anti-IgG2b mouse antibody (Alexa fluor 595; BD Biosciences, le Pont de Claix, France), washed again 3 times in PBS/0.5% BSA for 5 minutes, mounted on a slide with Moviol, and photographed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMR with 200 ×/0.30 objective lens; Leica, Heidelberg, Germany) (magnification × 200). Images were captured with an LEI-750 CE camera and LIDA vol. 54 software (Leica). Images were further processed with Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

IL-8 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Detection of IL-8 in sera and in culture media was assessed by means of an IL-8 ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's description (Beckman Coulter-Immunotech).

CD34+ and MK liquid cultures

Purified CD34+ cells were cultured in a serum-free medium either containing IL-1, IL-3, IL-6, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF), Flt3, stem cell factor (SCF), erythropoietin (Epo), thrombopoietin (Tpo) (RM-BO2; Mabio-International, Tourcoing, France) for their granulo-macrophagic, erythroid, and MK differentiation (9-factor [9F] medium) or containing IL-3, IL-6, IL-11, Tpo (RM-BO3; RTM/Mabio-International) for specific MK differentiation (MK medium). Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL antihuman IL-8–neutralizing polyclonal goat antibody (AF-208-NA; R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom), antihuman IL-8RA/CXCR1 (5A12-PE), or IL-8RB/CXCR2 (6C6-PE). Isotypic immunoglobulins were used as controls. On days 7 to 14 of the culture, cells were harvested, counted, and labeled with mAbs directed against surface differentiation markers or were prepared for cell cycle analysis. Supernatants, smears, and pellets were prepared for ELISA, cytologic, and molecular analysis.

Clonogenic MK colony-forming unit (CFU-MK) progenitors

MK progenitors were assessed in collagen matrix by means of the DM-CB00Ω kit (Mabio-International). CD34+ cells (5 × 103) were incubated in 1 mL serum-free collagen medium supplemented by IL-3 (2.5 ng) (Mabio-International), IL-6 (10 ng), and Tpo (50 ng) (Peprotech, Tebu International, Le Perray en Yvelines, France) with or without anti-CXCR1– or anti-CXCR2– neutralizing antibodies (10 μg/mL). IgG isotype was used as control (Pharmingen). Duplicate cultures were incubated for 10 to 12 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Standard May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining and immunocytochemistry using a CD41 mAb-FITC were performed for reliable and accurate identification of MK colonies.

MK ploidy quantification

DNA content of MK CD41+ cells (controlled by flow cytometry greater than 95% to 97% pure) was measured by propidium iodide (PI) staining on day 12 of the MK liquid culture. Cells (5 × 104) were fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol overnight at –20°C and incubated for 30 minutes in the dark at 4°C in PBS containing PI (50 μg/mL) (Molecular Probes Europe, Breda, The Netherlands) and RNAse A (100 μg/mL) (Sigma, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). Cells were gated and analyzed for ploidy and S phase percentages with WinMDI and Cylchred freewares (Nigel Garrahan; www.uwcm.ac.uk/uwcm/hg/hoy).

Antisense (AS) oligonucleotide treatment

To verify the oligonucleotide nontoxicity, CD34+ cells were incubated for 7 days in liquid medium containing cytokines and IL-8 antisense or control CG-matched randomized-sequence phosphorothioate oligonucleotides (Biognostik, Göttingen, Germany) at 2, 5, and 10 μM concentrations, and viability was assessed with trypan blue exclusion. The 5-μM concentration was thus determined to be efficient and nontoxic. Oligonucleotide sequence specificity was addressed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR), and specific inhibition due to the AS was also verified on the protein level by ELISA, according to the manufacturer's recommendation for highly expressed genes. To assess the IL-8 AS effect, purified CD34+ cells from patients or healthy donors were set up in double wells (at a cell density of 5 × 103/mL) and cultured for 14 days, with or without 5 μM IL-8 antisense or control oligonucleotides. Cultures were renewed every 3 days with 3 μM IL-8 antisense or control oligonucleotides. After 7 and 14 days of culture, cells were harvested, counted, and labeled with anti-CD41mAbs. Supernatants were stocked at –20°C; smears and pellets were prepared for cytological and molecular studies.

Primers and probes

Primers and probes were designed by means of primer Express software (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Courtaboeuf, France) and synthesized by PE Biosystems (Courtaboeuf, France). For human IL-8, the forward and reverse primers were 5′-CAC CGG AAG GAA CCA TTC TC-3′ and 5′-AAT CAG GAA GGC TGC CAA GA-3′, respectively, and the TaqMan probe was 6 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-TGA CTT CCA AGC TGG CCG TGG C-6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine (TAMRA). For human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), the forward and reverse primers were 5′-GAA GGT GAA GGT CGG AGT CA-3′ and 5′-GAA GAT GGT GAT GGG ATT TC-3′, respectively, and the TaqMan probe was 2,7-dimetoxy-4,5-dichloro-6-carboxyfluorescein (JOE)-CCG ACT CTT GCC CTT CGA AC-TAMRA.

RNA isolation and QRT-PCR assay

Total RNA from CD34+ cells (1 × 106; purity exceeding 98%) prepared according to Chomczynski and Sacchi42 was applied for reverse transcription and amplification by means of the TaqMan RT-PCR kit (PE Biosystems).43 Briefly, cDNA corresponding to reverse-transcribed total RNA was amplified in a 30-μL vol reaction in triplicate assays. IL-8 and GAPDH were amplified in the presence of 400 nM IL-8 primers or 200 nM GAPDH primers, 200 nM IL-8 probe, and 100 nM GAPDH probe. A no-template control and the unknown samples were also amplified in triplicate in a final volume of 30 μL. Thermal cycling conditions were performed as described previously.43 Amplifications were performed on an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence detector (PE Biosystems). During the assay, the linear increase in fluorescence signals (ΔRn) from the reporter dye was collected by a Prism 7700 (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany), and raw data were calculated by means of Sequence Detector Software 1.6.3 (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer's protocol. For each sample, data were normalized to the GAPDH housekeeping gene level.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant (Student t test).

Results

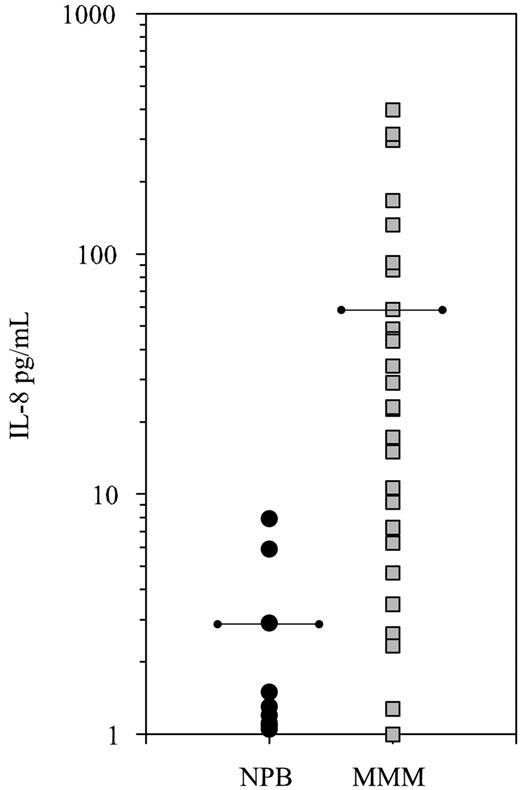

Serum IL-8 level is increased in patients with MMM

IL-8 was quantified in the serum of 32 patients with MMM and 10 healthy subjects by ELISA. As shown in Figure 1, the IL-8 level was heterogeneous but highly elevated in most analyzed patients, with a mean serum IL-8 value in patients with MMM 30-fold increased as compared with healthy subjects (60.20 ± 100 pg/mL versus 2.7 ± 2.5 pg/mL, respectively; P = .003).

Elevated IL-8 serum level in patients with MMM. Sera from 32 patients with MMM and from 10 healthy controls (NPB) were assayed for IL-8 by ELISA. Mean levels are indicated by the horizontal bars. The difference between patients with MMM and healthy subjects was significant (P = .003).

Elevated IL-8 serum level in patients with MMM. Sera from 32 patients with MMM and from 10 healthy controls (NPB) were assayed for IL-8 by ELISA. Mean levels are indicated by the horizontal bars. The difference between patients with MMM and healthy subjects was significant (P = .003).

Hematopoietic cells, including megakaryocytic cells and platelets, participate in IL-8 production in patients with MMM

The nature of the IL-8–producing cells was analyzed by intracellular flow cytometry, immunocytochemistry, and ELISA. Flow cytometry analysis, performed on total blood cells excluding the platelet gate, shows that in healthy donors IL-8 was expressed in CD15+ granulocytic (50% ± 26%; 14 ± 1.4 mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]; n = 3) and CD14+ monocytic (10% ± 6%; 47 ± 27 MFI; n = 3) cells. In patients with MMM, circulating CD41+ MK cells (30% ± 15%; 85 ± 54 MFI; n = 4) also participated with CD15+ (32% ± 3.7%; 73 ± 19 MFI; n = 4) and CD14+ cells (11% ± 3.6%; 117 ± 18 MFI; n = 4) in the IL-8 production. Absence of CD42b labeling on these cells eliminated a possible contamination by sticky platelets (data not shown). IL-8 detection in MMM MK cells was confirmed by double IL-8/CD41 labeling performed on blood mononuclear cells (Figure 2) as well as by ELISA performed on supernatants of CD41+ cells generated from CD34+ cell culture in MK conditions (651 ± 185 pg/mL in MMM MK cells versus 299 ± 59 pg/mL in NPB MK cells; n = 3, P < .05). Participation of MMM platelets in the IL-8 overproduction was supported by results showing that platelet-rich plasma (PRP) contains significantly higher levels of IL-8 than platelet-poor plasma (PPP) in patients or in PRP or PPP from healthy subjects (Table 1). This result was confirmed by a 5- to 70-fold higher IL-8 production per platelet in MMM as compared with healthy subjects and by an elevated IL-8 level in purified, washed MMM platelets (54 ± 4 pg/mL; n = 2) versus normal platelets (10 ± 2 pg/mL; n = 2).

Circulating MMM CD41+ megakaryocytic cells expressed IL-8 protein. Smears of blood mononuclear cells from patients with MMM were subjected to double labeling with anti-CD41 and anti–IL-8. The 3 panels show the same field of cells (magnification × 200). (A) Green fluorescent staining of anti-CD41–FITC. (B) Red-orange fluorescence staining of anti–IL-8–PE. (C) Double labeling of IL-8 and CD41 antigens. Slides were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMR, 200 × aperture .30, 400 × aperture .50; Leica, Heidelberg, Germany).

Circulating MMM CD41+ megakaryocytic cells expressed IL-8 protein. Smears of blood mononuclear cells from patients with MMM were subjected to double labeling with anti-CD41 and anti–IL-8. The 3 panels show the same field of cells (magnification × 200). (A) Green fluorescent staining of anti-CD41–FITC. (B) Red-orange fluorescence staining of anti–IL-8–PE. (C) Double labeling of IL-8 and CD41 antigens. Slides were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMR, 200 × aperture .30, 400 × aperture .50; Leica, Heidelberg, Germany).

IL-8 levels in PRP and PPP of patients with MMM or healthy subjects

. | IL-8, pg/mL . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample . | PRP* . | PPP . | |

| H1 | 46 | < 8 | |

| H2 | < 8 | < 8 | |

| H3 | < 8 | < 8 | |

| MMM1 | 252 | 72 | |

| MMM2 | 249 | 54 | |

| MMM4 | 324 | 77 | |

| MMM11 | 64 | < 8 | |

| MMM12 | 96 | < 8 | |

. | IL-8, pg/mL . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample . | PRP* . | PPP . | |

| H1 | 46 | < 8 | |

| H2 | < 8 | < 8 | |

| H3 | < 8 | < 8 | |

| MMM1 | 252 | 72 | |

| MMM2 | 249 | 54 | |

| MMM4 | 324 | 77 | |

| MMM11 | 64 | < 8 | |

| MMM12 | 96 | < 8 | |

H indicates healthy donor; MMM, patients with MMM.

IL-8 concentrations were assessed by means of an IL-8 ELISA kit. The threshold sensitivity for the IL-8 ELISA was ≥ 8 pg/mL.

Indicates significant difference between PRP and PPP values for H and MMM subjects; P < .05.

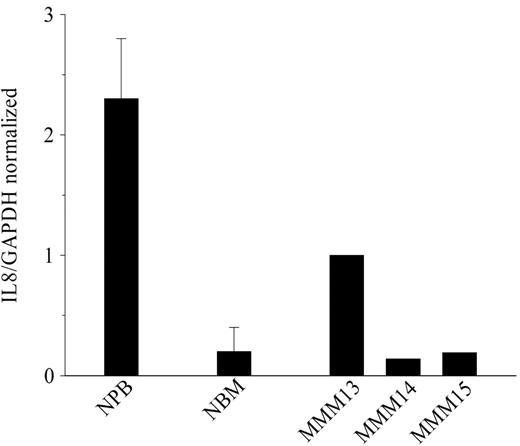

IL-8 is expressed in CD34+ cells from healthy subjects and patients with MMM

The high number of circulating CD34+ cells in patients' blood led us to analyze possible participation of these cells in IL-8 production. QRT-PCR showed that normal PB CD34+ expressed a higher relative IL-8 transcript level than their medullar counterparts (2.25 ± 0.5 versus 0.25 ± 0.25, respectively; P = .05; n = 3 pools of 6 to 7 healthy donors for NPB and n = 3 individual NBM) (Figure 3). In patients with MMM, IL-8 expression by PB CD34+ cells was heterogeneous and displayed intermediate or similar relative transcript levels for normal PB and BM expression, respectively (Figure 3). Intracellular IL-8 protein was detected by flow cytometry in CD34+ cells purified from either normal BM (36.6% ± 17%, 18 ± 0.5 MFI) or MMM PB (24.5% ± 16%, 30 ± 10 MFI). Evaluation of intracellular IL-8 protein expression in NPB CD34+ cells was not possible owing to the low number of recovered cells.

IL-8 gene expression in CD34+ cells from patients with MMM and healthy subjects. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed with appropriate primers for IL-8 and GAPDH as described in “Materials and methods.” Amplification results were calculated by means of Sequence Detector Software 1.6.3. Mean IL-8/GAPDH normalized values with standard deviations are plotted for NPB (n = 3 pools of 6 to 7 blood samples) and NBM (n = 3). The IL-8/GAPDH ratio was individually calculated for the 3 patients with MMM.

IL-8 gene expression in CD34+ cells from patients with MMM and healthy subjects. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed with appropriate primers for IL-8 and GAPDH as described in “Materials and methods.” Amplification results were calculated by means of Sequence Detector Software 1.6.3. Mean IL-8/GAPDH normalized values with standard deviations are plotted for NPB (n = 3 pools of 6 to 7 blood samples) and NBM (n = 3). The IL-8/GAPDH ratio was individually calculated for the 3 patients with MMM.

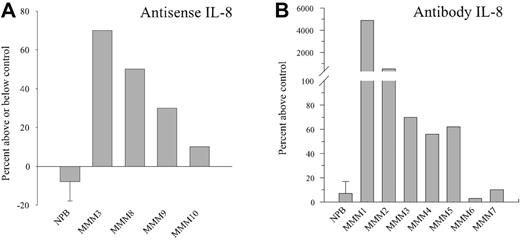

Inhibition of IL-8 expression/production increases the proliferation of MMM CD34+-derived cells and stimulates their megakaryocytic differentiation

The potential role of autocrine IL-8 on CD34+-derived cell proliferation was analyzed by adding either IL-8 AS oligonucleotides or neutralizing antibodies to purified CD34+ cells in 9F culture condition. Figure 4A shows that addition of 5μM AS, which was previously demonstrated to be the most effective nontoxic concentration, increased the number of CD34+-derived cells by 30% to 70% after 10 to 14 days of culture in 3 of the 4 tested patients whereas it did not alter the growth of normal CD34+-derived cells. Reduction of the IL-8 transcript level (R = 0.695, when normalized on GAPDH expression) and of the IL-8 protein level (30% to 77%, when quantified by ELISA) (Table 2) was detected in the AS-treated cells as compared with matched random control cells.

Effect of endogenous IL-8 inhibition by antisense oligonucleotides or neutralizing antibody on CD34+-derived cell proliferation. CD34+ cells purified from patients with MMM or NPB were cultured for 14 days in serum-free medium containing a cytokine cocktail (as described in “Materials and methods”) with or without IL-8 antisense (5 μM, panel A) or antihuman IL-8 antibody (10 μg/mL, panel B). Cells were harvested after 14 days of culture and counted. Bar graphs display mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from 3 independent experiments for normal PB. patients with MMM were individually analyzed.

Effect of endogenous IL-8 inhibition by antisense oligonucleotides or neutralizing antibody on CD34+-derived cell proliferation. CD34+ cells purified from patients with MMM or NPB were cultured for 14 days in serum-free medium containing a cytokine cocktail (as described in “Materials and methods”) with or without IL-8 antisense (5 μM, panel A) or antihuman IL-8 antibody (10 μg/mL, panel B). Cells were harvested after 14 days of culture and counted. Bar graphs display mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from 3 independent experiments for normal PB. patients with MMM were individually analyzed.

Inhibition of IL-8 production, in CD34+-derived cell culture, by either IL-8 antisense or anti-IL-8 antibody

. | IL-8 production . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Controls, pg/mL* . | With IL-8 antisense or antibody, pg/mL . | Inhibition, % . | ||

| Cultured with or without 5 μM IL-8 antisense | |||||

| H1 | 11 460 | 3270 | 71 | ||

| H2 | 1 800 | 1120 | 40 | ||

| H3 | 2 475 | 1284 | 50 | ||

| MMM3 | 4 652 | 1260 | 73 | ||

| MMM8 | 9 760 | 2280 | 77 | ||

| MMM9 | 3 176 | 2140 | 33 | ||

| MMM10 | 3 850 | 2850 | 25 | ||

| Cultured with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IL-8 antibody | |||||

| H1 | 11 680 | 592 | 94 | ||

| H2 | 12 786 | 4944 | 61 | ||

| H3 | 2 880 | 60 | 97 | ||

| H4 | 4 060 | < 8 | 100 | ||

| MMM1 | 2 995 | < 8 | 100 | ||

| MMM2 | 2 600 | < 8 | 100 | ||

| MMM3 | 4 020 | 120 | 97 | ||

| MMM4 | 10 080 | 180 | 98 | ||

| MMM5 | 5 740 | 930 | 83 | ||

| MMM6 | 3 950 | 3500 | 11 | ||

| MMM7 | 2 478 | 2000 | 19 | ||

. | IL-8 production . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Controls, pg/mL* . | With IL-8 antisense or antibody, pg/mL . | Inhibition, % . | ||

| Cultured with or without 5 μM IL-8 antisense | |||||

| H1 | 11 460 | 3270 | 71 | ||

| H2 | 1 800 | 1120 | 40 | ||

| H3 | 2 475 | 1284 | 50 | ||

| MMM3 | 4 652 | 1260 | 73 | ||

| MMM8 | 9 760 | 2280 | 77 | ||

| MMM9 | 3 176 | 2140 | 33 | ||

| MMM10 | 3 850 | 2850 | 25 | ||

| Cultured with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IL-8 antibody | |||||

| H1 | 11 680 | 592 | 94 | ||

| H2 | 12 786 | 4944 | 61 | ||

| H3 | 2 880 | 60 | 97 | ||

| H4 | 4 060 | < 8 | 100 | ||

| MMM1 | 2 995 | < 8 | 100 | ||

| MMM2 | 2 600 | < 8 | 100 | ||

| MMM3 | 4 020 | 120 | 97 | ||

| MMM4 | 10 080 | 180 | 98 | ||

| MMM5 | 5 740 | 930 | 83 | ||

| MMM6 | 3 950 | 3500 | 11 | ||

| MMM7 | 2 478 | 2000 | 19 | ||

See Table 1 footnote for abbreviations.

CD34+ cells purified from the peripheral blood of either patients with MMM or healthy subjects were cultured in serum-free medium containing cytokines in the presence and absence of IL-8 antisense or antihuman IL-8 antibody. After 14 days of culture, supernatants were harvested, and the IL-8 level was measured by ELISA. The threshold sensitivity for the IL-8 ELISA was ≥ 8 pg/mL.

Matched random controls for IL-8 antisense; isotypic controls for anti—IL-8 antibody.

To further substantiate the role of secreted IL-8 on CD34+ growth, we assessed the effect of an anti–IL-8–neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL) in such cultures. In contrast to NPB CD34+ cells, such treatment also significantly increased the number of CD34+-derived cells by 50% to 5000% in 5 of the 7 tested patients with MMM (Figure 4B). This effect, which was not observed in control isotype-treated cells, was maximal on day 14 of the culture. Increased cell proliferation in anti–IL-8 MMM treated cultures was correlated with a reduction in the IL-8 supernatant level (Table 2). Interestingly, the 2 unresponsive patients (MMM6 and MMM7) (Figure 4) exhibited a low IL-8 level reduction (Table 2). Even if theses values may be biased by a possible competition between the antibodies added in the culture and those used in the ELISA, they are correlated with the biologic response of patients.

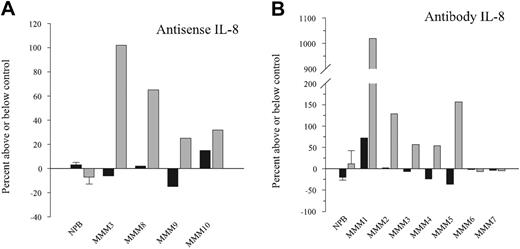

Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that a 14-day anti–IL-8 antibody treatment significantly reduced, by 82% ± 30% and 50% ± 4%, the number of MMM cells expressing the primitive multilineage Thy1 and CD34 antigens, respectively, as compared with IgG-treated control (P = .005). Such a reduction was not observed in normal PB CD34+ anti–IL-8–treated cultures. There was no modification in the percentage of cells expressing CD15, CD14, CD71, GPA, or CD41 (Figure 5) after anti–IL-8 antibody treatment in either MMM or normal cultures. In contrast, the expression level of the CD41/GpIIb megakaryocytic membrane glycoprotein was significantly increased after either an anti–IL-8 antibody or an AS oligonucleotide treatment in most of the analyzed patients with MMM (Figure 5). The CD41 expression increase was maximal on day 14 of the culture and was correlated with the presence of multinucleated differentiated megakaryocytes in anti–IL-8–treated MMM cultures (Figure 6A).

Effect of endogenous IL-8 inhibition by antisense oligonucleotides or neutralizing antibody on CD41 antigen expression levels. CD34+ cells purified from either MMM or NPB were cultured in serum-free medium containing a cytokine cocktail in the presence and absence of 5 μM IL-8 antisense (panel A) or 10 μg/mL antihuman IL-8 antibody (panel B). Cells were harvested after 14 days of culture and labeled with monoclonal antibody against CD41. The percentage (▪) and MFI ( ) of CD41+ cells were analyzed with Cellquest software by means of a FASCcalibur flow cytometer. Bar graphs display mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. patients with MMM were individually analyzed.

) of CD41+ cells were analyzed with Cellquest software by means of a FASCcalibur flow cytometer. Bar graphs display mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. patients with MMM were individually analyzed.

Effect of endogenous IL-8 inhibition by antisense oligonucleotides or neutralizing antibody on CD41 antigen expression levels. CD34+ cells purified from either MMM or NPB were cultured in serum-free medium containing a cytokine cocktail in the presence and absence of 5 μM IL-8 antisense (panel A) or 10 μg/mL antihuman IL-8 antibody (panel B). Cells were harvested after 14 days of culture and labeled with monoclonal antibody against CD41. The percentage (▪) and MFI ( ) of CD41+ cells were analyzed with Cellquest software by means of a FASCcalibur flow cytometer. Bar graphs display mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. patients with MMM were individually analyzed.

) of CD41+ cells were analyzed with Cellquest software by means of a FASCcalibur flow cytometer. Bar graphs display mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. patients with MMM were individually analyzed.

Effect of neutralizing anti–IL-8 or anti-CXCR1/anti-CXCR2 antibodies on the maturation of megakaryocytic cells derived from MMM CD34+ cells. Purified CD34+ cells from MMM and healthy subjects (NPB) were cultured for 14 days in serum-free medium containing a cytokine cocktail (9F or MK medium) in the absence or presence of neutralizing anti–IL-8 (panel A) or anti-CXCR1 or anti-CXCR2 (panel B) antibodies. The cells were cytocentrifuged and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa (magnification × 400). In panel B, the asterisk indicates the presence of MK cells with plump lobulated nucleus in MMM untreated cells, and the black arrow designates MK cells with polylobulated nucleus in the anti–IL-8– or anti-CXCR1 antibody–treated cultures in patients with MMM. Similar polylobulated nuclei were also obtained in anti-CXCR2 antibody–treated MMM cultures.

Effect of neutralizing anti–IL-8 or anti-CXCR1/anti-CXCR2 antibodies on the maturation of megakaryocytic cells derived from MMM CD34+ cells. Purified CD34+ cells from MMM and healthy subjects (NPB) were cultured for 14 days in serum-free medium containing a cytokine cocktail (9F or MK medium) in the absence or presence of neutralizing anti–IL-8 (panel A) or anti-CXCR1 or anti-CXCR2 (panel B) antibodies. The cells were cytocentrifuged and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa (magnification × 400). In panel B, the asterisk indicates the presence of MK cells with plump lobulated nucleus in MMM untreated cells, and the black arrow designates MK cells with polylobulated nucleus in the anti–IL-8– or anti-CXCR1 antibody–treated cultures in patients with MMM. Similar polylobulated nuclei were also obtained in anti-CXCR2 antibody–treated MMM cultures.

CXCR2 receptor is overexpressed in PB MMM CD34+ cells

To analyze why CD34+ cells from healthy donors did not response to anti–IL-8 treatment in contrast to MMM CD34+ cells, we compared the expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 IL-8 receptors on CD34+ cells from MMM and healthy subjects. Table 3 shows that most of NPB CD34+ cells expressed low levels of CXCR1 and that a low percentage of cells weakly expressed CXCR2. In contrast, CXCR2 was overexpressed in a high percentage of CD34+ cells from the majority of tested patients with MMM (P = .05). Interestingly, patient MMM1 shows 2 distinct populations; 1 of them, corresponding to 8% of CD34+ cells, expressed a 30-fold higher CXCR2 expression level than NPB CD34+ cells (Table 3).

Expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 IL-8 receptors on CD34+ cells

. | CXCR1 . | . | CXCR2 . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | % . | MFI . | % . | MFI . | ||

| NPB1 | 97 | 18 | 30 | 8 | ||

| NPB2 | 70 | 8 | 18 | 7 | ||

| NPB3 | 60 | 10 | Ud | Ud | ||

| NPB4 | 89 | 11 | Ud | Ud | ||

| NPB5 | 94 | 13 | 25 | 6 | ||

| MMM1 | ||||||

| Population 1 | 39 | 10 | 71 | 10 | ||

| Population 2 | Ud | Ud | 8 | 183 | ||

| MMM2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| MMM3 | 90 | 32 | 96 | 39 | ||

| MMM4 | ND | ND | 73 | 19 | ||

| MMM5 | 97 | 14 | 95 | 10 | ||

| MMM6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| MMM7 | 90 | 21 | 4 | 14 | ||

| MMM8 | 99 | 20 | 77 | 7 | ||

| MMM9 | 7 | 18 | 20 | 41 | ||

| MMM10 | 88 | 15 | 97 | 16 | ||

. | CXCR1 . | . | CXCR2 . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | % . | MFI . | % . | MFI . | ||

| NPB1 | 97 | 18 | 30 | 8 | ||

| NPB2 | 70 | 8 | 18 | 7 | ||

| NPB3 | 60 | 10 | Ud | Ud | ||

| NPB4 | 89 | 11 | Ud | Ud | ||

| NPB5 | 94 | 13 | 25 | 6 | ||

| MMM1 | ||||||

| Population 1 | 39 | 10 | 71 | 10 | ||

| Population 2 | Ud | Ud | 8 | 183 | ||

| MMM2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| MMM3 | 90 | 32 | 96 | 39 | ||

| MMM4 | ND | ND | 73 | 19 | ||

| MMM5 | 97 | 14 | 95 | 10 | ||

| MMM6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| MMM7 | 90 | 21 | 4 | 14 | ||

| MMM8 | 99 | 20 | 77 | 7 | ||

| MMM9 | 7 | 18 | 20 | 41 | ||

| MMM10 | 88 | 15 | 97 | 16 | ||

CD34+ cells purified from either MMM or NPB were labeled with PE-conjugated anti-CXCR1 and anti-CXCR2 or isotype control. The percentage and MFI of positive cells were analyzed on 5 × 104 cells with FACScalibur flow cytometer. Note that patient MMM1 exhibited 2 distinct CXCR2-expressing populations.

Ud indicates undetectable; ND, not determined.

CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors participate in the control of MMM MK cell proliferation and differentiation

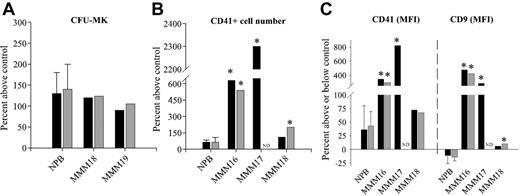

To address the potential involvement of IL-8 receptors in the control of MMM MK proliferation/differentiation, we analyzed the effect of specific neutralizing antibodies for CXCR1 and CXCR2 on clonal CFU-MKs and on megakaryocytes derived from CD34+ cell growth in specific MK medium. Figure 7A shows that both antibodies similarly stimulated the growth of colonies that were identified as CFU-MK by CD41 immunolabeling from NPB or MMM CD34+ cells. Neutralization of both receptors also stimulated the proliferation of CD41+ megakaryocytes derived from CD34+ cells; this increase, although low in healthy subjects, is greatly elevated in 2 of the 3 patients with MMM. In fact, in MMM17, cell proliferation exceeded that of untreated control cells by up to 2300% on day 14 of the culture when neutralizing antibodies for CXCR1 were added to the culture (Figure 7B). This increased proliferation is associated with a significantly higher expression level of CD41 and CD9 MK antigens (Figure 7C).44

Effect of neutralizing anti-CXCR1 and anti-CXCR2 antibodies on CFU-MK growth and MK cell proliferation and differentiation in samples from healthy and MMM subjects. (A) CFU-MK colony formation from peripheral blood CD34+ cells of patients with MMM and healthy subjects. Purified CD34+ cells (5 × 103) were cultured in serum-free collagen medium with or without anti-CXCR1–neutralizing (black bar) or anti-CXCR2–neutralizing (gray bar) antibodies as described in “Materials and methods.” Colonies were scored at day 12 after staining with an anti-CD41 mAb–FITC and May-Grünwald-Giemsa. (B) (C) MK cell proliferation (panel B) and differentiation (panel C) from peripheral blood CD34+ cells of MMM and healthy subjects. Purified CD34+ cells were cultured for 12 days under megakaryocytic liquid culture conditions in the presence or absence of anti-CXCR1–neutralizing (black bar) or anti-CXCR2–neutralizing (gray bar) antibodies as described in “Materials and methods.” Cells were harvested after 14 days of culture, and cell numbers were determined by counting viable cells by trypan blue exclusion. After cells were labeled with monoclonal antibody against CD41, the percentage and MFI of CD41+ cells were analyzed with Cellquest software by means of a FASCcalibur flow cytometer. The expression level of CD41 and CD9 antigens on days 12 to 14 of culture compared with isotype control is expressed as MFI. In all experiments, results were expressed as the percentage above or below untreated control cells. Bar graphs display mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments for normal blood cells. patients with MMM were individually analyzed. *P < .05. ND indicates not done.

Effect of neutralizing anti-CXCR1 and anti-CXCR2 antibodies on CFU-MK growth and MK cell proliferation and differentiation in samples from healthy and MMM subjects. (A) CFU-MK colony formation from peripheral blood CD34+ cells of patients with MMM and healthy subjects. Purified CD34+ cells (5 × 103) were cultured in serum-free collagen medium with or without anti-CXCR1–neutralizing (black bar) or anti-CXCR2–neutralizing (gray bar) antibodies as described in “Materials and methods.” Colonies were scored at day 12 after staining with an anti-CD41 mAb–FITC and May-Grünwald-Giemsa. (B) (C) MK cell proliferation (panel B) and differentiation (panel C) from peripheral blood CD34+ cells of MMM and healthy subjects. Purified CD34+ cells were cultured for 12 days under megakaryocytic liquid culture conditions in the presence or absence of anti-CXCR1–neutralizing (black bar) or anti-CXCR2–neutralizing (gray bar) antibodies as described in “Materials and methods.” Cells were harvested after 14 days of culture, and cell numbers were determined by counting viable cells by trypan blue exclusion. After cells were labeled with monoclonal antibody against CD41, the percentage and MFI of CD41+ cells were analyzed with Cellquest software by means of a FASCcalibur flow cytometer. The expression level of CD41 and CD9 antigens on days 12 to 14 of culture compared with isotype control is expressed as MFI. In all experiments, results were expressed as the percentage above or below untreated control cells. Bar graphs display mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments for normal blood cells. patients with MMM were individually analyzed. *P < .05. ND indicates not done.

Neutralization of CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors restores altered MMM MK ploidy

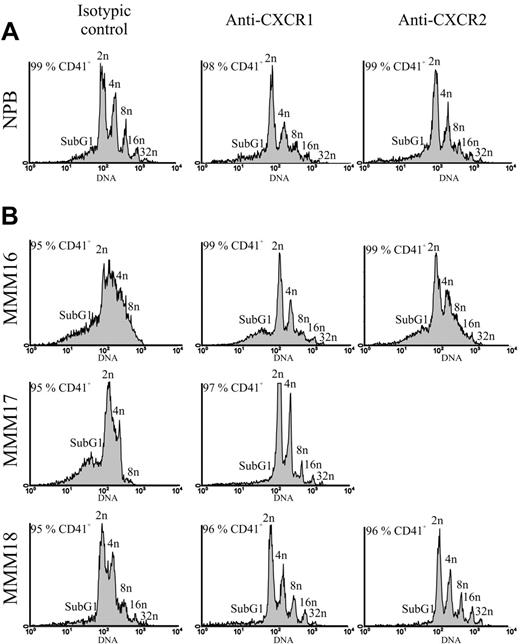

To further analyze the role of CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors on MMM MK cell differentiation/maturation, we studied the effect of both antibodies on the ploidy level of CD41+ megakaryocytes derived from NPB or MMM CD34+ cell culture in MK conditions. Our results show that after 14 days of culture, MMM CD41+ MK cells (greater than 95% pure) exhibited a lower ploidy level than their normal counterparts, especially for 2 (MMM16 and MMM17) of the 3 analyzed patients (Figure 8). This low ploidy level was associated with a high percentage of 2n cells in S phase in all studied patients as compared with NPB (Table 4). Surprisingly, a 14-day treatment with either CXCR1 or CXCR2 antibodies restored the ploidization of MMM MK cells since it increased by 2 to 4 the percentage of higher-than-8n CD41+ MK cells with the existence of 16n and 32n cells in treated cultures versus isotypic control cultures (Figure 8B; Table 4). This increase in ploidy level was associated with the presence of mature multinucleated MK cells in MMM cultures treated with either the anti-CXCR1 or the anti-CXCR2 antibody as compared with untreated cells, which exhibited an abnormal nuclear lobulation (Figure 6B). It is noteworthy that such treatment also induced a reduction of the sub-G1 peak that defined the proportion of apoptotic/dead cells and of the percentage of 2n MK cells in S phase, especially in patients MMM16 and MMM17 in whom ploidy was the most altered (Table 4).

Effect of anti-CXCR1 and anti-CXCR2 antibodies on the ploidy distribution of CD41+ MK cells derived from normal or MMM CD34+ cell culture. Polyploidy was evaluated by flow cytometry analysis, at days 12 to 14 of culture, on CD41+ MK cells grown in either the absence or the presence of anti-CXCR1 and anti-CXCR2 antibodies (10 μg/mL). CD41+ MK cells were stained with PI as described in “Materials and methods.” Histograms show the DNA content of CD41+ MK cells derived from normal (panel A) and MMM CD34+ (panel B) cells. One representative experiment from 3 separate experiments is shown for NPB. patients with MMM were individually analyzed.

Effect of anti-CXCR1 and anti-CXCR2 antibodies on the ploidy distribution of CD41+ MK cells derived from normal or MMM CD34+ cell culture. Polyploidy was evaluated by flow cytometry analysis, at days 12 to 14 of culture, on CD41+ MK cells grown in either the absence or the presence of anti-CXCR1 and anti-CXCR2 antibodies (10 μg/mL). CD41+ MK cells were stained with PI as described in “Materials and methods.” Histograms show the DNA content of CD41+ MK cells derived from normal (panel A) and MMM CD34+ (panel B) cells. One representative experiment from 3 separate experiments is shown for NPB. patients with MMM were individually analyzed.

Ploidy distribution of CD41+ MK cells derived from healthy subjects and patients with MMM with and without anti-CXCR1 and anti-CXCR2 antibodies

. | . | 2n ploidy . | . | 4n ploidy . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Lower than 2n ploidy, sub-G1 phase, % . | % . | S phase % . | % . | S phase % . | Greater than 8n ploidy, % . | ||

| NPB | ||||||||

| Control | 28±3 | 61±2 | 36±1 | 25±0 | 43±3 | 14±2 | ||

| Anti-CXCR1 | 22±5 | 58±3 | 25±5 | 27±0 | 39±10 | 15±2 | ||

| Anti-CXCR2 | 21±6 | 61±5 | 26±6 | 26±1 | 41±4 | 14±2 | ||

| MMM16 | ||||||||

| Control | 43 | 69 | 80 | 26 | 60 | 5 | ||

| Anti-CXCR1 | 33 | 63 | 31 | 24 | 40 | 13 | ||

| Anti-CXCR2 | 24 | 53 | 40 | 32 | 45 | 15 | ||

| MMM17 | ||||||||

| Control | 40 | 83 | 57 | 15 | 18 | 2 | ||

| Anti-CXCR1 | 3 | 69 | 31 | 23 | 26 | 8 | ||

| Anti-CXCR2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| MMM18 | ||||||||

| Control | 29 | 64 | 55 | 27 | 45 | 9 | ||

| Anti-CXCR1 | 19 | 62 | 38 | 22 | 28 | 16 | ||

| Anti-CXCR2 | 19 | 57 | 33 | 26 | 35 | 17 | ||

. | . | 2n ploidy . | . | 4n ploidy . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Lower than 2n ploidy, sub-G1 phase, % . | % . | S phase % . | % . | S phase % . | Greater than 8n ploidy, % . | ||

| NPB | ||||||||

| Control | 28±3 | 61±2 | 36±1 | 25±0 | 43±3 | 14±2 | ||

| Anti-CXCR1 | 22±5 | 58±3 | 25±5 | 27±0 | 39±10 | 15±2 | ||

| Anti-CXCR2 | 21±6 | 61±5 | 26±6 | 26±1 | 41±4 | 14±2 | ||

| MMM16 | ||||||||

| Control | 43 | 69 | 80 | 26 | 60 | 5 | ||

| Anti-CXCR1 | 33 | 63 | 31 | 24 | 40 | 13 | ||

| Anti-CXCR2 | 24 | 53 | 40 | 32 | 45 | 15 | ||

| MMM17 | ||||||||

| Control | 40 | 83 | 57 | 15 | 18 | 2 | ||

| Anti-CXCR1 | 3 | 69 | 31 | 23 | 26 | 8 | ||

| Anti-CXCR2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| MMM18 | ||||||||

| Control | 29 | 64 | 55 | 27 | 45 | 9 | ||

| Anti-CXCR1 | 19 | 62 | 38 | 22 | 28 | 16 | ||

| Anti-CXCR2 | 19 | 57 | 33 | 26 | 35 | 17 | ||

Data for healthy subjects are the mean of 3 distinct experiments; data for MMM subjects are presented individually. See Table 3 for abbreviations.

Discussion

The numerous biologic activities of IL-8 on HP mobilization, regulation, and angiogenesis prompted us to analyze its potential role in MMM, a myeloproliferative syndrome characterized by severe alteration of these processes. In the present study, we showed that IL-8 level is highly increased in the serum of patients with MMM and that hematopoietic cells participated in its production. MMM platelets that express higher level of IL-8 than their normal counterparts are likely to participate in such an overproduction. However, the fact that there is no clear correlation (r =–0.203; n = 19) between the average platelet count (9000 to 524 000/mm3) and the IL-8 serum level in patients with MMM suggests that other cells also participate in such an increased production. Actually, whereas circulating MMM granulocytes/monocytes, MK cells, and CD34+ cells expressed IL-8 protein level similar to that of their normal counterparts, their elevated numbers in patients' PB1,11 suggest that they take part in the IL-8 overproduction. Our results showing that CD34+ and megakaryocytically derived CD34+ cells from unmobilized normal blood or from patients with MMM expressed IL-8 protein, reinforce recent data reporting IL-8 production by CD34+ cells and MK cells derived from cord blood or BM.45,46 IL-8 is known to also be produced by BM stromal and endothelial cells. Since myeloproliferation is associated with myelofibrosis and neoangiogenesis, the participation of stromal and endothelial cells in the elevated serum IL-8 level observed in MMM cannot be excluded.

IL-8 is reported to exert an inhibitory effect on hematopoiesis and specially on MK proliferation.47,48 However, in synergy with M-CSF, it could also act on promotion of monocyte/macrophage growth and differentiation.49 As for other chemokines, it has been suggested that such a controversial stimulatory or inhibitory effect of IL-8 on hematopoiesis is concentration dependent.49

In the present study, we used antisense and antibodies against IL-8 to analyze its potential role in the myeloproliferative process that characterizes MMM. We show that both treatments strongly increase the proliferation of MMM PB CD34+-derived cells in 9F liquid culture medium, whereas they do not alter the proliferation of their normal counterparts. The stimulating effect of anti–IL-8–neutralizing antibody was higher than that of specific AS. This could be explained by the QRT-PCR and ELISA data showing that the highest nontoxic AS concentration (5 μM) used in this experiment was not adequately effective on IL-8 expression inhibition, which is frequently observed in active protein synthesis. Anti–IL-8 treatments also increased the expression level of CD41 and CD9, 44 2 MK differentiation/maturation markers, and the number of multinucleated MK cells, suggesting that IL-8 participates in the altered MK maturation observed in patients with MMM.

The stimulating effect of anti–IL-8 treatment is observed late in liquid culture and is barely evident on myeloid clonogenic progenitors in semisolid medium (data not shown). This observation suggests that endogenous IL-8 negatively regulates the proliferation of hematopoietic cells, which are more mature than clonogenic progenitors. Furthermore, our unpublished data (S.E., 2000) indicate that the addition of human recombinant monocytic IL-8 (up to 20 ng/mL) does not affect the CFU-GM and erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E) growth in semisolid medium. These observations are in agreement with the previously stated assumption and confirm earlier observations from Ratajczak and Ratajczak.50

Of the 10 tested patients, 2 (MMM6 and MMM7) showed no response to anti–IL-8 antibody treatment while 2 others (MMM9 and MMM10) responded weakly to IL-8 AS. It is interesting to note that IL-8 production was weakly inhibited in these patients, in contrast to the responsive ones in whom IL-8 production was highly inhibited (Table 2). The healthy subjects did not respond to anti–IL-8 treatment even though the IL-8 secretion was inhibited in NPB CD34+-derived cultures. We therefore investigated whether an altered expression of IL-8 receptors could account for such a different response to anti–IL-8 treatment. We showed that while CXCR2 IL-8 receptor expression was weakly detectable on NPB CD34+ cells, it was overexpressed on most MMM CD34+ cells (Table 3) and its expression was maintained during the culture since 86% ± 12% of MMM cells still expressed CXCR2 on day 12 as compared with 13% ± 2% in their normal counterparts. Interestingly, MMM7 and MMM9 patients who did not respond or responded weakly to anti–IL-8 treatment demonstrated a low CXCR2 expression, as in normal CD34+ cells. These results are in agreement with Sanchez et al's20 and Broxmeyer et al's35 studies showing that the inhibitory effect of CXC chemokines on myelopoiesis is mediated by CXCR2.

Involvement of IL-8 receptors in this process, especially in the altered MMM MK proliferation/differentiation, was further addressed by using neutralizing antibodies against CXCR1 or CXCR2 receptors on megakaryocyte-derived CD34+ cells. While anti-CXCR1 or anti-CXCR2 treatments similarly affect the clonal growth of NPB and MMM CFU-MKs, neutralization of both receptors greatly stimulated the proliferation of CD41+ megakaryocytically derived CD34+ cells from patients with MMM as compared with healthy subjects. The significantly higher expression levels of CD41 and CD9 MK differentiation marker in MMM-treated cultures confirmed the involvement of both receptors in stimulating the MK differentiation/maturation. Interestingly, both antibodies also restored the altered polyploidization of MMM CD41+ MK cells. Such an effect was observed particularly in MMM16 and MMM17 patients, who exhibited the lowest ploidy as compared with MMM18, or in NPB MK cells, which exhibit a higher or “normal” endomitotic process with the presence of 32n cells. The reduction in the percentage of cells in sub-G1 phase and of 2n cells in S phase in MMM-treated culture suggested that neutralization of IL-8 receptors reduced the apoptosis of dysmatured MK cells and favored their maturation by stimulating the endomitosis versus the proliferation process. The presence of multinucleated mature MK cells in treated cultures reinforces such an assumption.

Neutralization of either CXCR1 or CXCR2 stimulated the maturation of MMM megakaryocytes, restored their ploidy, and reduced their percentage in sub-G1 phase, which strongly suggests that their ligands, including IL-8, participate in the altered MK growth. In contrast to cytokines, the relation between chemokines and their receptors is of a “polygamous” type since chemokine receptors bind several different chemokines and chemokines bind several different receptors.51 Therefore, it could be hypothesized that other CXC chemokines participate in the MMM MK dysregulation. The serum levels of NAP2, quantified by densitometry on protein array (data not shown) and of ENA-78 (1354 ± 1021 pg/mL and 1393 ± 843 pg/mL, respectively) were similar in MMM and healthy subjects. In contrast, those of GRO alpha and granulocyte chemotactic protein 2, which are higher potent agonists for CXCR2 than for CXCR1, 52 are increased in patients (645 ± 320 pg/mL and 590 ± 180 pg/mL, respectively) as compared with healthy subjects (120 ± 40 pg/mL and 164 ± 130 pg/mL, respectively). Although the implication of these chemokines in MMM pathogenesis cannot be excluded, our results showing that inhibition of either IL-8 or its receptors resulted in similar biologic effects supports a major role for IL-8 in the process described.

MMM is a heterogeneous and puzzling disease in which myeloproliferation is associated with an alteration of MK maturation and with the extramedullary migration of HP to the spleen and liver. Considering the inhibitory role of IL-8 in hematopoiesis, the presence of myeloproliferation associated with a high level of IL-8 in MMM could appear paradoxical. Interestingly, abnormal production of IL-8 has also been reported in a number of proliferative hematologic disorders such as polycythemia vera, where its action is still not well understood.53 The most significant biologic effect of IL-8 and its receptors suggested by our results is that they participate in the altered MK cell proliferation and differentiation in MMM. Therefore, it can be suggested that IL-8, most likely in synergy with other cytokines/chemokines overproduced in this disease, contributed to maintaining the CD34+ progenitor compartment in a proliferative immature state by a feedback mechanism. Our results showing that the anti–IL-8 treatment significantly reduced the number of MMM cells expressing the primitive multilineage Thy1 and CD34 antigens are in agreement with such a hypothesis. It has been recently reported that the binding of PF4 to IL-8 could impair IL-8–dependent signaling in CD34+ progenitors through the formation of IL-8/PF4 heterodimers or heterotetramers.54 A similar process could be evoked in MMM, in which PF4 is highly increased in the BM microenvironment.55,56 Interestingly, intramedullary accumulation of PF4 is suggested to promote the displacement of hematopoiesis to other organs such as liver and spleen.54 Such a hypothesis is of pathophysiologic relevance with regard to MMM, in which medullary aplasia is associated with myeloid metaplasia in spleen and liver.12

Our results showed that the altered MK maturation observed in patients with MMM could be reproduced in vitro in CD34+ cell–derived cultures, corroborating the intrinsic alteration of MMM HPs. To our knowledge, this is the first time that IL-8 and its receptors are reported to be involved in MMM-altered MK growth. This observation, which is relevant to a significant subpopulation of patients exhibiting striking MK abnormalities, probably reflects the heterogeneous character of the disease. Even though the primary molecular defect is still unknown in MMM, it is suggested that the clonal expansion of HP and their deregulated differentiation are favored by the overproduction and release of hematopoietic, fibrogenic, and angiogenic cytokines/chemokines by hematopoietic cells, including CD34+ cells, monocytes, and megakaryocytes.7,8,57-59 Excessive release/leakage of these growth factors within the bone marrow, especially by dysplastic and necrotic MK cells, would lead to the uncontrolled stromal activation resulting in generation of secondary myelofibrosis. In that respect, our results showing that IL-8 and its receptors play a role in the deregulated MK differentiation process in a significant number of patients with MMM are important for a better understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease. Furthermore, they open new targeted therapeutic prospects for this rare and still incurable hemopathy.

Appendix

Members of the French INSERM Network on Myeloid Metaplasia with Myelofibrosis: Dr Jean-Loup Demory, St Vincent Hospital, Lille, France; Dr Brigitte Dupriez, Dr Schaffner Hospital, Lens, France; Dr Vincent Praloran, Dr Chrystèle Bilhou-Nabéra, and Dr Eric Lippert, Hematology Laboratory, and Dr Jean-François Viallard, Victor Segalen University, Bordeaux, France; Dr Dominique Bordessoule, Dupuytren Hospital, Limoges, France; Dr Jean Brière, Beaujon Hospital, Clichy, France; Dr Jean-François Emile, Paul Brousse Hospital, Villejuif, France; Dr Marie-Claire Martyré, Institut Curie, Paris, France.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 28, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4415.

A complete list of the memers of the French INSERM Research Network on MMM appears in the “Appendix.”

Supported by grants from the Association Nouvelles Recherches Biomédicales (ANRB), Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC) no. 9806, and from Groupement d'Interet Scientifique (GIS)–Institut des Maladies Rares no. 03/GIS/PB/SJ/n°35. S.E. was awarded a fellowship from the Fondation de France.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank the members of the French INSERM Research Network on MMM and of European Myelofibrosis Network (EUMNET) for providing blood samples from patients with MMM. We express gratitude to Dr J. J. Lataillade (Centre de Transfusion Sanguine des Armées Jean-Julliard [CTSAJean-Julliard], Clamart, France) for continuously supplying buffy coats from the peripheral blood of healthy adults. We are greatly indebted to Dr Y. Masse (Service de Chirurgie Orthopédique du CHR d'Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France), for regularly providing normal bone marrow surgical materials. We thank Dr J. Chagraoui for her helpful advice with the fluorescence microscopy and Dr C. Boucheix for his critical reading of the manuscript.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal