Abstract

Inhibitory natural killer cell receptor (NKR)–expressing cells may induce a graft-versus-leukemia/tumor (GVL/T) effect against leukemic cells and tumor cells that have mismatched or decreased expression of HLA class I molecules and may not cause graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) against host cells that have normal expression of HLA class I molecules. In our study, we were able to expand inhibitory NKR (CD94/NKG2A)–expressing CD8+ T cells from granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF)–mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells (G-PBMCs) by more than 500-fold using stimulation by an anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody with interleukin 15 (IL-15). These expanded and purified CD94-expressing cells attacked various malignant cell lines, including solid cancer cell lines, as well as the patients' leukemic cells but not autologous and allogeneic phytohemagglutinin (PHA) blasts in vitro. Also, these CD94-expressing cells prevented the growth of K562 leukemic cells and CW2 colon cancer cells in NOD/SCID mice in vivo. On the other hand, the CD94-expressing cells have low responsiveness to alloantigen in mixed lymphocyte culture (MLC) and have high transforming growth factor (TGF)–β1– but low IL-2– producing capacity. Therefore, CD94-expressing cells with cytolytic activity against the recipient's leukemic and tumor cells without enhancement of alloresponse might be able to be expanded from donor G-PBMCs.

Introduction

The regulation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and graftversus-leukemia (GVL) effect is the most important issue in allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo SCT).

It recently has been shown that inhibitory natural killer cell receptors (NKRs) on NK cells negatively regulate NK cell functions through their binding to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules.1-3 It also has been revealed that T cells, especially memory CD8+ T cells, expressed NKRs. NK-like activity and T-cell receptor (TCR)–mediated killing activity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) expressing inhibitory NKRs were suppressed by HLA class I recognition by the NKRs. Inhibitory NKR-positive cells could attack class I–negative target cells but not the same class I–positive cells.4-7

Partially HLA-matched bone marrow transplantation (BMT) resulted in a large expansion of donor-derived CTLs expressing CD158b inhibitory NKRs, which did not cause GVHD but allowed a discriminatory GVL reaction.8 Also, based on the rule of NKR incompatibility, the GVL effectors may be operational in patients who have undergone HLA-mismatched hematopoietic cell transplantation.9 Mixed lymphocyte reaction and anti-CD3 mAb–redirected cytotoxicity were inhibited by engagement of transgenic CD158b molecules in CD158b transgenic mice.10,11 Ruggeri et al12 reported surprisingly good clinical results that indicated no relapse, no rejection, and no acute GVHD after HLA-haplotype–mismatched transplantations with NKR ligand incompatibility in the GVH direction for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients. They also reported that donor allogeneic NK cells attacked host antigen-presenting cells (APCs), resulting in the suppression of GVHD. With regard to the clinical advantage of NKR ligand incompatibility in allo SCT from an unrelated donor, Davies et al13 showed negative data without using antithymocyte globulin (ATG), while Giebel et al14 showed positive data using ATG as part of GVHD prophylaxis.

In our previous studies, the proportion of CD158b, which is a specific receptor for HLA-C, on CD8+ T cells was found to be increased in patients with chronic GVHD (cGVHD). Also, the proportion of CD94/NKG2A, which is a specific receptor for HLA-E,15 on T cells was larger in cGVHD patients with good prognosis than in cGVHD patients with poor prognosis. Furthermore, the addition of CD94-enriched fractions to CD94-depleted fractions suppressed the proliferation of T cells in MLCs.16-19 Therefore, NKR-expressing cells might be involved in the regulation of allogeneic response after allo SCT. That is, inhibitory NKR induction on alloreactive CTLs may prevent GVHD and mismatch of NKRs, and ligands may be useful for induction of the GVL effect during allo SCT.20-22

Although granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cell (G-PBMC) grafts contain at least 10 times more T cells than do standard bone marrow grafts, the incidence and severity of acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT) are not higher than those observed with allogeneic marrow. Also, there is a possibility that allogeneic PBSCT prevents leukemia relapse by induction of the GVL effect.23-25 It was previously reported that G-PBMC leukapheresis products contain large numbers of CD14+ cells, which suppress donor T-cell proliferation in a dose-dependent fashion.26,27 Also, we have shown that the induction of a costimulatory molecule, CD28 responsive complex, in CD4+ cells appears to be suppressed by the presence of CD14+ cells in G-PBMCs.28 Therefore, it seems useful to use G-PBMCs as a source of lymphocytes in order to manipulate cells for cell therapy to modulate GVHD and GVL. In this study, we expanded NKR-expressing T cells from donor G-PBMCs and investigated their cytolytic characteristics and regulatory functions.

Materials and methods

Donors and G-CSF mobilization

Peripheral blood stem cell donors were administered rhG-CSF (Lenograstim, 1.2 million units (MU)/10 μg, Chugai or Filgrastim, 1 MU/10 μg, Kirin-Sankyo, Japan) by subcutaneous injection at a dose of 10 μg/kg once daily for 4 to 5 days. Leukapheresis was performed from day 4 of rhG-CSF administration, and G-PBMCs were obtained from the first leukapheresis. PBMCs before administration of G-CSF (PreG-PBMC) and G-PBMC samples were cryopreserved to enable simultaneous testing.

Immunofluorescent staining for flow cytometric analysis and monoclonal antibodies

The phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated monoclonal antibody (mAb) HP-3D9 (anti-CD94) was obtained from Ancell (Bayport, MN), and Z199 (anti-NKG2A), ON72 (anti-NKG2D), Z231 (anti-NKp44), and C1.7 (anti-CD244) were obtained from Immunotec (Marseilles, France). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD3, anti-CD8 mAb, and anti–HLA-A, -B, -C mAb (G46-2.6) were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Anti-CD56 mAb and anti–granzyme A mAb were obtained from Becton Dickinson (BD, San Jose, CA). Anti–HLA class I mAb BRA-23/9 and W6/32 were obtained from NeoMarkers (Fremont, CA), and rat anti–HLA class I mAb (YTH862.2) was obtained from Serotec (Oxford, England). Anti-CD3 mAb OKT3 was obtained from Ortho Biotech (Raritan, NJ). Anti-NKG2C and anti-NKG2D mAb were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Intracellular granzyme A was stained using cytofix/cytoperm reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Becton Dickinson). The fluorescence intensity of the cells was analyzed using a FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson). Statistical analysis was performed using Student t test.

Immunomagnetic cell sorting

Purified CD14+ cells (> 95% CD14+, as determined by flow cytometric analysis), CD8+ cells (> 90% CD8+), and CD94+ cells (> 90% CD94+) were obtained by magnetic cell sorting (MACS) using magnetic microbeads according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

Induction of CD94/NKG2A on CD8+ T cells by stimulation with immobilized anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody and IL-15

For coating with anti-CD3 mAb, 24-well flat-bottom plates or tissue culture flasks were preincubated with OKT3 (1 μg/mL) in 100 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane]-HCl buffer (pH 9.5) for 16 hours at 4° C. Seven paired PreG-PBMCs and G-PBMCs (1 × 106/mL) were cultured on 24-well plates in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum with 5 ng/mL of recombinant human IL-15 (R&D Systems) at 37° C for 7 days. CD8+ cells (500 × 103/mL) purified from G-PBMC cultures were established on 24-well plates with or without the use of 0.45-μm micropore membranes (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Purified CD14+ cells (300 × 103) derived from the same G-PBMCs were added to the culture directly or through the membrane.

Expansion of CD94-expressing cells from G-PBMCs

Six paired PreG-PBMCs and G-PBMCs (2.5 × 106) were cultured with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb (1 μg/mL) and IL-15 (5 ng/mL) in RPMI 1640 with 5% human AB serum in T25 culture flasks for 7 days. After 5 days of culture, 5 mL of fresh medium was added. Absolute numbers of CD94+/CD3+, CD94+/CD8+, NKG2A+/CD3+, and NKG2A+/CD8+ cells on day 7 were calculated from multiplication of total number of expanded cells and the proportion of these cells in expanded cells.

PCR reaction and TCR spectratyping

First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 60 ng RNA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 2.5 μM Random 9 mer, and 0.25U/μL avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa RNA PCR Kit, Japan). Then polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the cDNA was carried out using a sense primer (5′-CAGCATGAGGGGCTACCCG-3′) and an antisense primer (5′-GTGTGAGGAAGGGGGTCATG-3′) for exon 4 of HLA-E.29 A sense primer (5′-TTCGAGCAAGAGATGGCCACGGCT-3′) and an antisense primer (5′-ATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACAT-3′) for β-actin were used as an internal standard.

For analysis of the TCR-VB repertoire, PCR amplification of the cDNA was carried out using corresponding primers to the variable regions of TCR-VB and CB.30 Samples consisting of 1 μL of PCR product with a size standard (labeled ROX) and paraformamide were heated at 95° C for 2 minutes and then placed for a moment on ice. TCR spectratyping was performed using a capillary electrophoresis system (PRISM310 Genetic Analyzer, ABI, Foster City, CA).

Evaluation of cytolytic activity using 4-hour 51Cr release assay

After 7 days of stimulation by immobilized anti-CD3 mAb with IL-15 in a T25 flask, CD94-expressing cells were purified by MACS. The cytolytic activities of purified CD94-expressing cells were tested against 51Cr-labeled human malignant cell lines, patients' own leukemic cells, autologous PHA blasts, and allogeneic PHA blasts (5 × 103). K562 cells, an erythroleukemic cell line, were cultured with interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (0.2 μg/mL) for 2 days to induce HLA class I expression. An HLA-Cw3 signal peptide (VMAPRTLIL), which can bind to HLA-E, and an irrelevant B15 peptide (VTAPRTVLL)31 were synthesized by Kurabo (Osaka, Japan) (purity, 95%). Several leukemic cell lines and solid cancer cell lines were obtained from Riken (Tsukuba, Japan).

Mixed lymphocyte culture

Responder CD94-expressing cells and CD94-depleted cells (50 × 103) were cultured with 50 × 103 irradiated (30 Gy) allogeneic, third-party PBMC stimulators in 200 μL of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum in round-bottom 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, New York). After 2 days of incubation at 37° C in 5% CO2, cultures were pulsed with 3H-thymidine (1.0 μCi [0.037 MBq]/well) for the final 16 hours. The cells were then harvested, and 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured in triplicate using a 196 gas flow counter (Packard Instrument, Downers Grove, IL). Anti–TGF-β1 mAb (25 μg/mL, R&D Systems) was added to the MLC medium using CD94-expressing cells as responders.

Measurement of cytokine concentrations

Cytokine concentrations in MLC (50 × 103 responders and 50 × 103 irradiated stimulators) after 2 days and in culture medium (50 × 103) stimulated by phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (10 ng/mL) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL) after 1 day were estimated. TGF-β1 was measured by using a human TGF-β1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems), and other cytokines were measured by using a LiquiChip Human Cytokine System (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

NOD/SCID mice

Female 5- to 8-week-old NOD/SCID mice were purchased from Clea (Tokyo, Japan). Breeding and maintenance were performed in a microisolator under sterile conditions. K562 cells or CW2 colon cancer cells with or without purified CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs were suspended in 0.5 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of the NOD/SCID mice. NOD/SCID mice did not receive irradiation or anti-ASGM1 antibody.

Results

Induction of CD94/NKG2A expression on CD8+ T cells in G-PBMCs by immobilized anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody stimulation with IL-15

We found that the proportion of CD94/NKG2A-expressing CD3+/CD8+ T cells in G-PBMCs was increased after immobilized anti-CD3 mAb stimulation (Table 1). Although there was no difference between the proportions of CD94/NKG2A-expressing T cells in PBMCs obtained from 7 donors before administration of G-CSF (PreG-PBMCs) and after administration of G-CSF (G-PBMCs) without stimulation, the proportions of CD94/NKG2A-expressing T cells derived from G-PBMCs after 7 days of stimulation with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb both with and without IL-15 were significantly higher than the proportions of CD94/NKG2A-expressing T cells derived from PreG-PBMCs (Table 1). We also found that the proportions of CD94/NKG2A-expressing CD8+ T cells that had been purified from G-PBMCs before culture were increased by immobilized anti-CD3 mAb stimulation with IL-15 (Table 2). The addition of 3 × 105 purified CD14+ cells derived from the same G-PBMCs to purified CD8+ T cells induced much more CD94/NKG2A expression on those purified CD8+ T cells. This effect of purified CD14+ cells tended to be inhibited by the use of a membrane (Table 2). These results suggest that CD14+ cells play an important role in the induction of CD94/NKG2A expression on T cells and that this effect might require at least partial contact between responder cells and CD14+ cells. Furthermore, it was revealed that CD94/NKG2A expression on purified CD8+ T cells from G-PBMCs could be induced in our culture system. TCR engagement has been reported to play an important role in the induction of inhibitory NKRs on CD8+ T cells.6 Several cytokines, such as IL-12 and IL-15, are known to be CD94/NKG2A-inducible cytokines.7,32 It is possible that IL-15 induces inhibitory NKRs on CD8+ T cells derived from G-PBMCs during T-cell activation by the immobilized anti-CD3 mAb.

Proportion of CD94/NKG2A-expressing cells in paired PreG- and G-PBMC before and after stimulation by anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody

. | Before . | . | After anti-CD3 stimulation . | . | Anti-CD3 and IL-15 . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface marker . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | |||

| CD94+/CD3+ | 5.7 ± 3.1 | 4.6 ± 1.9 | 8.4 ± 4.4 | 17.2 ± 8.7* | 24.2 ± 10.4 | 32.8 ± 8.2† | |||

| CD94+/CD8+ | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 7.3 ± 4.0 | 15.2 ± 8.4* | 17.6 ± 10.0 | 24.2 ± 5.6‡ | |||

| NKG2A+/CD3+ | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 1.9 | 6.3 ± 5.0 | 11.3 ± 7.1 | 16.9 ± 7.7‡ | |||

| NKG2A+/CD8+ | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 5.1 ± 4.3 | 8.6 ± 3.1 | 13.6 ± 6.3* | |||

. | Before . | . | After anti-CD3 stimulation . | . | Anti-CD3 and IL-15 . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface marker . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | |||

| CD94+/CD3+ | 5.7 ± 3.1 | 4.6 ± 1.9 | 8.4 ± 4.4 | 17.2 ± 8.7* | 24.2 ± 10.4 | 32.8 ± 8.2† | |||

| CD94+/CD8+ | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 7.3 ± 4.0 | 15.2 ± 8.4* | 17.6 ± 10.0 | 24.2 ± 5.6‡ | |||

| NKG2A+/CD3+ | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 1.9 | 6.3 ± 5.0 | 11.3 ± 7.1 | 16.9 ± 7.7‡ | |||

| NKG2A+/CD8+ | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 5.1 ± 4.3 | 8.6 ± 3.1 | 13.6 ± 6.3* | |||

Values indicate the percentage of CD94 or NKG2A-expressing cells (means ± SDs, n = 7). Significant difference were noted when comparing the value of PreG and G-PBMC after stimulation with and without IL-15 (*P < .01; ‡P < .05, †P < .1).

Induction of CD94/NKG2A expression on purified CD8+ cells from G-PBMC

. | . | . | Addition of CD14+ cells . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface marker . | Before . | After . | Without membrane . | With membrane . | |

| CD94+/CD8+ | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 9.1 ± 5.8* | 19.7 ± 9.3† | 11.7 ± 6.0‡ | |

| NKG2A+/CD8+ | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 2.7† | 10.1 ± 6.8† | 5.0 ± 3.5‡ | |

. | . | . | Addition of CD14+ cells . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface marker . | Before . | After . | Without membrane . | With membrane . | |

| CD94+/CD8+ | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 9.1 ± 5.8* | 19.7 ± 9.3† | 11.7 ± 6.0‡ | |

| NKG2A+/CD8+ | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 2.7† | 10.1 ± 6.8† | 5.0 ± 3.5‡ | |

Values indicate the percentage of CD94 or NKG2A-expressing cells after anti-CD3 stimulation in the presence of IL-15 (means ± SDs, n = 7). Significant differences were noted when comparing the value of before and after stimulation; CD8+ cell only and addition of purified 3 × 105 CD14+ cells; without membrane; and the contact inhibition by the membrane.

P < .01.

P < .05.

P < .1.

Expansion of CD94-expressing cells from G-PBMCs

PreG-PBMCs and G-PBMCs contained almost equal numbers of CD94/NKG2A-expressing T cells before stimulation. CD94/NKG2A-expressing CD8+ T cells from both PreG-PBMCs and G-PBMCs were expanded by more than 100-fold after 7 days of culture. Moreover, a significantly greater number of CD94/NKG2A-expressing T cells was obtained from G-PBMCs than from PreG-PBMCs (Table 3). CD94+ cells (> 90% CD94+) were obtained by MACS using magnetic microbeads, and more than 80% of CD94-expressing cells coexpressed CD8 (data not shown). The CD94-depleted cells contained only low CD94-expressing CD8+ cells (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI], CD94-depleted cells vs CD94-expressing cells, 24.7 ± 7.2 vs 234.1 ± 30.5, n = 7). In contrast, most of these CD94+ cells did not express CD56. Furthermore, these CD94+ cells contained granzyme A, which is an important enzyme for induction of apoptosis of target cells in the cytoplasm.33 Also, CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs had a large repertoire of TCR-Vβ, as revealed by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis using 26 kinds of TCR-Vβ primer pairs (data not shown). These expanded CD8+ T cells expressed NKG2D and CD244 but did not express CD158a, CD158b, NKB1, CD161, nor NKp44 (data not shown).

Expansion of CD94/NKG2A-expressing cells from paired PreG- and G-PBMC

. | Before, mean absolute no. cells ± × 106 . | . | After stimulation, mean absolute no. cells ± × 106 (mean fold expression) . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface marker . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | ||

| CD94+/CD3+ | 0.048 ± 0.026 | 0.041 ± 0.012 | 2.87 ± 1.38 (59.8) | 5.51 ± 2.62* (134.4) | ||

| CD94+/CD8+ | 0.020 ± 0.007 | 0.010 ± 0.004 | 2.63 ± 1.25 (131.5) | 5.20 ± 2.36† (520.0) | ||

| NKG2A+/CD3+ | 0.021 ± 0.012 | 0.018 ± 0.010 | 2.09 ± 1.10 (99.5) | 4.20 ± 2.44* (233.3) | ||

| NKG2A+/CD8+ | 0.0052 ± 0.0036 | 0.0036 ± 0.0012 | 1.90 ± 1.02 (365.4) | 3.98 ± 2.21* (1105.6) | ||

. | Before, mean absolute no. cells ± × 106 . | . | After stimulation, mean absolute no. cells ± × 106 (mean fold expression) . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface marker . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | PreG . | G-PBMC . | ||

| CD94+/CD3+ | 0.048 ± 0.026 | 0.041 ± 0.012 | 2.87 ± 1.38 (59.8) | 5.51 ± 2.62* (134.4) | ||

| CD94+/CD8+ | 0.020 ± 0.007 | 0.010 ± 0.004 | 2.63 ± 1.25 (131.5) | 5.20 ± 2.36† (520.0) | ||

| NKG2A+/CD3+ | 0.021 ± 0.012 | 0.018 ± 0.010 | 2.09 ± 1.10 (99.5) | 4.20 ± 2.44* (233.3) | ||

| NKG2A+/CD8+ | 0.0052 ± 0.0036 | 0.0036 ± 0.0012 | 1.90 ± 1.02 (365.4) | 3.98 ± 2.21* (1105.6) | ||

Cultures were started from 2.5 × 106 mononuclear cells. Values indicate absolute number of cells before and after culture. Significant differences were noted when comparing the value of PreG and G-PBMC after stimulation (*P < .05, †P < .01).

Characteristics of cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against K562 leukemic cells

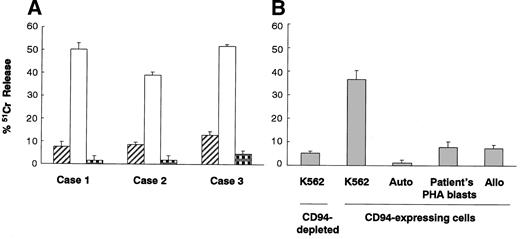

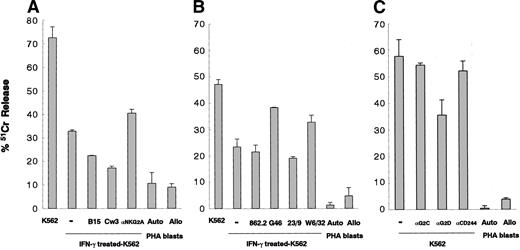

We investigated the characteristics of cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells expanded from donor G-PBMCs. The cytolytic activity level of purified CD94-expressing cells detected by a standard 4-hour 51Cr release assay against HLA class I–deficient K562 cells was found to be always higher than that of CD94-depleted cells and also higher than that against autologous PHA blasts (Figure 1A). Furthermore, the cytolytic activity level of CD94-expressing cells against allogeneic PHA blasts was as low as that against auto PHA blasts (Figure 1B). HLA class I expression is inducible on K562 cells by IFN-γ. The MFIs of HLA class I molecules on untreated K562 and IFN-γ–treated K562 cells were 21.8 ± 14.6 (n = 6) and 90.1 ± 25.5 (n = 6), respectively. Although we did not show the surface expression level of HLA-E on HLA class I–expressing cells, we could show HLA-E mRNA induction in HLA class I–expressing K562 cells in an RT-PCR experiment (data not shown). Therefore, the leader peptide of HLA class I stabilizes HLA-E expression and subsequently may be able to induce a higher level of HLA-E expression on HLA class I–expressing cells. The cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells against IFN-γ–treated K562 cells was attenuated compared with that against untreated K562 cells. Furthermore, HLA-Cw3 peptide (0.3 mM), which is a signal sequence of HLA-C and makes a complex with HLA-E as a ligand for CD94/NKG2A, suppressed the cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells against HLA class I–expressing K562 cells. The suppressive effect of Cw3 peptide was higher than that of an irrelevant B15 peptide. In contrast, anti-NKG2A mAb (10 μg/mL) restored the HLA class I protective effect against IFN-γ–treated K562 cells (Figure 2A). Also, anti–HLA class I mAbs (G46-2.6 and W6/32, 20 μg/mL) restored the cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells against IFN-γ–treated K562 cells that had increased mRNA of HLA-E, while other anti–HLA class I mAbs (YTH862.2 and BRA-23/9, 20 μg/mL) did not have any effect (Figure 2B). Furthermore, anti-NKG2D mAb suppressed the cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells against K562 cells, while anti-NKG2C mAb and anti-CD244 mAb did not have any effect (20 μg/mL) (Figure 2C).

Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against K562 leukemic cells and PHA blasts. (A) Cytolytic activities of CD94-depleted cells (▨) and CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against K562 cells (□) and autologous PHA blasts ( ). (B) Cytolytic activities of CD94-depleted cells and CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against K562 cells, autologous PHA blasts, patient's PHA blasts, and allogeneic third-party PHA blasts. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

). (B) Cytolytic activities of CD94-depleted cells and CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against K562 cells, autologous PHA blasts, patient's PHA blasts, and allogeneic third-party PHA blasts. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against K562 leukemic cells and PHA blasts. (A) Cytolytic activities of CD94-depleted cells (▨) and CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against K562 cells (□) and autologous PHA blasts ( ). (B) Cytolytic activities of CD94-depleted cells and CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against K562 cells, autologous PHA blasts, patient's PHA blasts, and allogeneic third-party PHA blasts. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

). (B) Cytolytic activities of CD94-depleted cells and CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against K562 cells, autologous PHA blasts, patient's PHA blasts, and allogeneic third-party PHA blasts. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

Characteristics of cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against K562 leukemic cells. (A) Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against untreated K562 cells, IFN-γ–treated K562 cells, IFN-γ–treated K562 cells with HLA-B15 peptide (0.3 mM), with HLA-Cw3 peptide (0.3 mM), and with anti-NKG2A mAb (10 μg/mL) against autologous PHA blasts and allogeneic PHA blasts. (B) Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against untreated K562 cells, IFN-γ–treated K562 cells, and IFN-γ–treated K562 cells with anti–HLA class I mAbs (YTH862.2, G46-2.6, BRA-23/9, and W6/32, 20 μg/mL) and against autologous PHA blasts and allogeneic PHA blasts. (C) The cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against K562 cells, against K562 cells with anti-NKG2C, anti-NKG2D, and anti-CD244 mAbs (20 μg/mL), against autologous PHA blasts and allogeneic PHA blasts. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

Characteristics of cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against K562 leukemic cells. (A) Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against untreated K562 cells, IFN-γ–treated K562 cells, IFN-γ–treated K562 cells with HLA-B15 peptide (0.3 mM), with HLA-Cw3 peptide (0.3 mM), and with anti-NKG2A mAb (10 μg/mL) against autologous PHA blasts and allogeneic PHA blasts. (B) Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against untreated K562 cells, IFN-γ–treated K562 cells, and IFN-γ–treated K562 cells with anti–HLA class I mAbs (YTH862.2, G46-2.6, BRA-23/9, and W6/32, 20 μg/mL) and against autologous PHA blasts and allogeneic PHA blasts. (C) The cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against K562 cells, against K562 cells with anti-NKG2C, anti-NKG2D, and anti-CD244 mAbs (20 μg/mL), against autologous PHA blasts and allogeneic PHA blasts. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against various leukemic cell lines, solid cancer cell lines, and the patient's leukemic cells

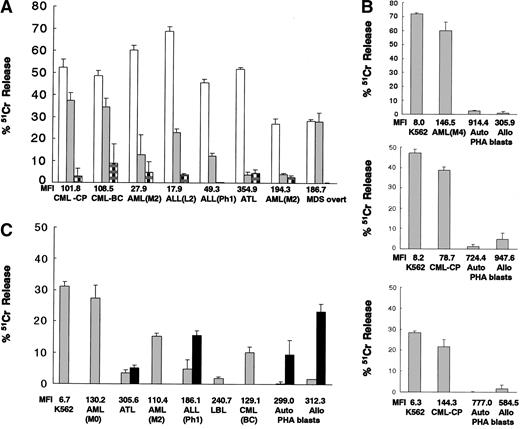

We analyzed the cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against 7 human leukemic cell lines and 3 solid cancer cell lines. Cytolytic activities against HLA class Ilow cells (MFI < 50; K562 and CW2 colon cancer cells) were more than 30% (effector-to-target, 10:1). On the other hand, cytolytic activities against HLA class Iintermediate cells (50 < MFI < 150; HL60, KCL22, HEL, and U937 leukemic cells) were 20% to 30%, and cytolytic activities against HLA class Ihigh cells (MFI > 200; J111 and BALL-1 leukemic cells and RC2 and 3TKB renal cancer cells) were less than 10% (data not shown).

We then investigated the cytolytic activities of HLA-matched donor CD94-expressing cells against the patient's chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cells derived from bone marrow cells before allo SCT in the chronic phase and against the patient's leukemic cells of CML myeloid blastic crisis (CML-BC), acute myelogenous leukemia (AML, M2), acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL, L2), Ph1-positive ALL, adult T-cell leukemia (ATL), another AML (M2), and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) overt leukemia. Expanded and purified CD94-expressing cells derived from each donor attacked K562 cells and the patients' own leukemic cells to varying degrees, depending on the type of tumor (the tumors having different expression levels of HLA class I and probably having different expression levels of adhesion molecules and stimulatory NKR ligands) but did not attack auto PHA blasts (Figure 3A). Also, allogeneic third-party CD94-expressing cells attacked the patients' primary AML (M0, M2, M4) and CML (CP and BC) leukemic cells. However, these cells did not attack ALL (L1) cells, ATL cells, lymphoblastic leukemia lymphoma (LBL) cells, auto PHA blasts, or allo PHA blasts. Anti–HLA class I mAb partially restored this killing activity against ALL (Ph1) leukemic cells, auto PHA blasts, and allo PHA blasts (Figure 3B-C). These expanded donor and allogeneic CD94-expressing cells attacked HLA class I molecule–lacking K562 leukemic cells and also the patient's leukemic cells that were not HLA class Ihigh cells (MFI < 200) as PHA blasts.

Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against the patients' leukemic cells. (A) Cytolytic activities of HLA-matched donor CD94-expressing cells expanded from 8 different donor G-PBMCs against K562 cells (□), the patients' own leukemic cells (▦) , and autologous PHA blasts ( ). (B, C) Cytolytic activities of allogeneic third-party CD94-expressing cells expanded from 4 different donor G-PBMCs against K562 cells, the patients' primary leukemic cells, autologous PHA blasts, and allogeneic PHA blasts. Addition of anti–HLA class I mAbs (W6/32, 20μg/mL) (▪). MFIs of HLA class I on target cells are indicated. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

). (B, C) Cytolytic activities of allogeneic third-party CD94-expressing cells expanded from 4 different donor G-PBMCs against K562 cells, the patients' primary leukemic cells, autologous PHA blasts, and allogeneic PHA blasts. Addition of anti–HLA class I mAbs (W6/32, 20μg/mL) (▪). MFIs of HLA class I on target cells are indicated. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

Cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs against the patients' leukemic cells. (A) Cytolytic activities of HLA-matched donor CD94-expressing cells expanded from 8 different donor G-PBMCs against K562 cells (□), the patients' own leukemic cells (▦) , and autologous PHA blasts ( ). (B, C) Cytolytic activities of allogeneic third-party CD94-expressing cells expanded from 4 different donor G-PBMCs against K562 cells, the patients' primary leukemic cells, autologous PHA blasts, and allogeneic PHA blasts. Addition of anti–HLA class I mAbs (W6/32, 20μg/mL) (▪). MFIs of HLA class I on target cells are indicated. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

). (B, C) Cytolytic activities of allogeneic third-party CD94-expressing cells expanded from 4 different donor G-PBMCs against K562 cells, the patients' primary leukemic cells, autologous PHA blasts, and allogeneic PHA blasts. Addition of anti–HLA class I mAbs (W6/32, 20μg/mL) (▪). MFIs of HLA class I on target cells are indicated. The data represented are the means ± SDs (effector-to-target ratio is 10:1).

Proliferation in MLC and cytokine productive capacity of CD94-expressing cells

Proliferation of T cells detected by 3H-thymidine incorporation was suppressed in MLC using CD94-expressing cells as responders compared with that in the case of using CD94-depleted cells as responders (2697 ± 1124 vs 6586 ± 2283 cpm, P < .01, n = 6). TGF-β1 concentration in MLC medium using CD94-expressing cells as responders was significantly higher than that in MLC medium using CD94-depleted cells as responders (383.2 ± 144.3 vs 236.4 ± 89.6 pg/mL, P < .05, n = 8). IL-2 and IFN-γ concentrations in MLC medium were not significantly different. On the other hand, IL-2 concentration in culture medium stimulated by PMA and ionomycin using CD94-depleted cells was significantly higher than that in culture medium using CD94-expressing cells (13 485.9 ± 10 640.4 vs 1767.7 ± 223.8 pg/mL, P < .05, n = 8). Furthermore, it was revealed that anti–TGF-β1 mAb could restore T-cell proliferation in MLCs using CD94-expressing cells as responders (2697 ± 1124 vs 3470 ± 1262 cpm, P < .01, n = 6).

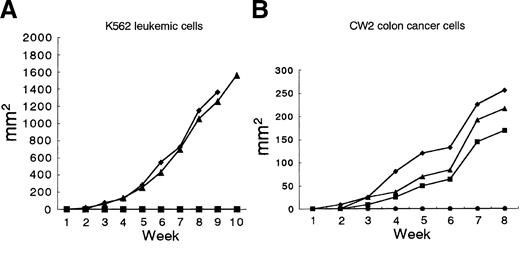

Inhibition of growth of K562 leukemic cells and CW2 colon cancer cells by CD94-expressing cells in NOD/SCID mice

NOD/SCID mice were coinjected subcutaneously with K562 cells and purified CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs. CD94-expressing cells inhibited the growth of K562 cells completely (ratio of CD94-expressing cells to K562 cells: 1 × 107 to 2 × 107) in NOD/SCID mice (Figure 4A). CD94-expressing cells also inhibited the growth of CW2 colon cancer cells completely (ratio of CD94-expressing cells to CW2 cells: 0.5 × 107 to 1 × 107) in NOD/SCID mice (Figure 4B).

CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs prevent growth of K562 leukemic cells and CW2 colon cancer cells in NOD/SCID mice. (A) Mice were subcutaneously injected with 2 × 107 K562 cells only (♦ and ▴; died after 9 and 13 weeks, respectively) or with 1 × 107 CD94-expressing cells (2 mice, ▪, survived more than 30 weeks). (B) Mice were subcutaneously injected with 1 × 107 CW2 colon cancer cells only (♦, ▴, and ▪; died after 9, 9, and 14 weeks, respectively) or with 0.5 × 107 CD94-expressing cells (3 mice, •, survived more than 30 weeks).

CD94-expressing cells expanded from G-PBMCs prevent growth of K562 leukemic cells and CW2 colon cancer cells in NOD/SCID mice. (A) Mice were subcutaneously injected with 2 × 107 K562 cells only (♦ and ▴; died after 9 and 13 weeks, respectively) or with 1 × 107 CD94-expressing cells (2 mice, ▪, survived more than 30 weeks). (B) Mice were subcutaneously injected with 1 × 107 CW2 colon cancer cells only (♦, ▴, and ▪; died after 9, 9, and 14 weeks, respectively) or with 0.5 × 107 CD94-expressing cells (3 mice, •, survived more than 30 weeks).

Discussion

In this study, we found that the proportion of CD94/NKG2A-expressing CD3+/CD8+ T cells in G-PBMCs was increased after immobilized anti-CD3 mAb stimulation with IL-15. We also found that CD14+ cells derived from G-PBMCs play an important role in the induction of CD94/NKG2A expression on purified CD8+ T cells. Therefore, CD8+ T cells derived from G-PBMCs could express CD94/NKG2A after stimulation. Also, we were able to expand CD94-expressing CD8+ T cells from donor G-PBMCs by more than 500-fold. The absolute number of CD94-expressing T cells after stimulation from G-PBMCs was significantly higher than that from PreG-PBMCs. It is possible that a greater number of CD14+ cells in G-PBMCs than in PreG-PBMCs can stimulate the first signal through TCR. This TCR engagement has been reported to play an important role in the induction of inhibitory NKRs on CD8+ T cells.6 Although we showed a CD94-inducing effect of CD14+ cells in a contact-dependent manner, other factors such as cytokines may be implicated in this effect. Also, it is not clear enough whether G-CSF has an effect on progenitor cells of CD94/NKG2A-expressing cells. Nevertheless, G-PBMCs, which are easy to obtain and store at the time of PBSC collection from the donor, may be a useful source for the expansion of inhibitory NKR-expressing cells.

These expanded and purified CD94-expressing cells had CD8 expression but not CD56 expression on their surfaces. Also, these CD94-expressing cells contained granzyme A in the cytoplasm and had a large repertoire of TCR-Vβ as revealed by RT-PCR analysis using 26 kinds of TCR-Vβ primer pairs. Furthermore, these expanded CD8 T cells did not express other killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) such as CD158a, CD158b, or NKB1 or NK cell–activating markers such as CD161 or NKp44, but they did express NK cell–activating receptors NKG2D and CD244. Therefore, these cells have both inhibitory receptors (CD94/NKG2A) and activating receptors (NKG2D). The cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells depends at least partially on NKG2D-activating NKR, because anti-NKG2D mAb suppressed this activity. However, it is possible that other receptors that were not analyzed in this study are involved in the killing activity.

HLA-E, a CD94/NKG2A ligand, preferably bound to a peptide derived from the signal sequences of most HLA-A, -B, -C, and -G and was also up-regulated by these peptides.31 We investigated the characteristics of cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells using IFN-γ–induced HLA class I molecule–expressing K562 cells that had increased mRNA of HLA-E. HLA-C signal peptide was found to suppress the cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells against IFN-γ–induced HLA class I molecule–expressing K562 cells. Also, anti-NKG2A mAb and some anti–HLA class I mAbs partially restored the cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells against HLA class I molecule–protected K562 cells. In addition, results of analysis of the cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against 10 malignant cell lines, including 3 solid cancer cell lines, indicated that this killing activity roughly depended on the expression of HLA class I molecules on the cell surface. However, the cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells does not depend entirely on the expression of HLA class I molecules. The cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells may be regulated by the balance among the expression levels of HLA class I, HLA-E itself, and certain molecules on target cells.

We also investigated the cytolytic activities of CD94-expressing cells against 17 patients' primary leukemic cells. Donor and allogeneic CD94-expressing cells could attack patients' CML cells and AML cells but could not attack some patients' leukemic cells such as ATL cells, which had high expression levels of HLA class I molecules. Also, the addition of anti–HLA class I mAb induced restoration of the cytolytic activity of CD94-expressing cells against PHA blasts and ALL (Ph1) but not ATL cells. Although these CD94-expressing cells attacked HLA class Ilow-intermediate patients' leukemic cells, the killing activity varied, depending on the type of leukemia. Patients' leukemic cells have different expression levels of HLA class I, and they may have different expression levels of other regulatory molecules for the killing activities of CD94-expressing cells. Therefore, not only HLA class I molecules on leukemic cells but also other molecules such as adhesion molecules and stimulatory NKR ligands such as MHC class I chain–related protein (MIC34 ) and activating molecules on effector cells might be important for the regulation of these killing activities.

In vivo analysis revealed that CD94-expressing cells prevented the growth of K562 leukemic cells and also CW2 colon cancer cells in NOD/SCID mice. These models suggest that CD94-expressing cells may therefore have a graft-versus-leukemia/tumor effect.

In addition, the CD94-expressing cells exhibited low proliferative capacity in MLC and high TGF-β1 productivity with attenuated IL-2 productivity. These cells therefore have low responsiveness to alloantigens and may also have a suppressive effect on HLA class I–induced alloresponse.

We previously reported increased expression of CD158 and CD94/NKG2A on T cells in chronic GVHD patients with good prognosis and showed that these inhibitory NKR-expressing cells have a suppressive effect on allogeneic response in MLC.16-19 Therefore, inhibitory NKR expression during allogeneic stimulation after allo SCT may play an important role in modulation of GVHD. Based on clinical and experimental data, we speculate that these inhibitory NKR-expressing cells have a GVL/T effect against leukemic cells and tumor cells that have decreased expression levels of HLA class I molecules and do not enhance GVHD against host cells that have normal expression levels of HLA class I molecules.

Elucidation of cytolytic characteristics, proliferative characteristics, and cytokine productivity of inhibitory NKR-expressing cells might provide clues about how to control the delicate balance between GVHD and GVL. It may be possible to use expanded CD94-expressing cells from donor G-PBMCs, which contain a large number of T cells, for allogeneic cell therapy instead of naive donor lymphocyte infusion to induce the GVL effect without enhancing GVHD. Donor G-PBMCs, which are an alternative stem cell source for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, might also be a useful source of lymphocytes for expanding NKR-expressing cells for cell therapy for some patients whose leukemic cells and tumor cells have escaped from allogeneic recognition by usual cytotoxic T cells because of the low expression level of HLA class I molecules.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 8, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3870.

Supported in part by a grant from the Idiopathic Hematological Disease and Bone Marrow Transplantation Research Committee of the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan; and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan; and a grant from Kirin Brewery Company (Tokyo, Japan).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Ms M. Yamane, Ms M. Mayanagi, and Ms R. Miura for their technical assistance.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal