Abstract

Although leukocytes adhere in arteries in various vascular diseases, to date no endogenous proinflammatory molecule has been identified to initiate leukocyte adhesion in the arterial vasculature. This study was undertaken to assess angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced leukocyte adhesion in arterioles in vivo. Rats received intraperitoneal injections of Ang II; 4 hours later, leukocyte recruitment in mesenteric microcirculation was examined using intravital microscopy. Ang II (1 nM) produced significant arteriolar leukocyte adhesion of mononuclear cells. Using function-blocking monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against different rat cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), we discovered that this effect was dependent on P-selectin and β2-integrin. In postcapillary venules, Ang II also induced leukocyte infiltration, which was reduced by P-selectin and by β2- and α4-integrin blockade. Interestingly, neutrophils were the primary cells recruited in venules. Although β2-integrin expression in peripheral leukocytes of Ang II-treated animals was not altered, it was increased in peritoneal cells. Immunohistochemical studies revealed increased P-selectin, E-selectin, intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression in response to Ang II in arterioles and venules. These findings provide the first evidence that Ang II causes leukocyte adhesion to the arterial endothelium in vivo at physiologically relevant doses. Therefore, Ang II may be a key molecule in cardiovascular diseases in which leukocyte adhesion to the arteries is a characteristic feature. (Blood. 2004;104:402-408)

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is the major cause of myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, accounting for nearly half of all deaths in developed countries. Atherogenesis is a complex process characterized by the formation of a neointimal lesion that progressively occludes the arterial lumen. One of the earliest stages of atherogenesis is endothelial dysfunction, which is thought to cause an inflammatory response consisting of lipid accumulation and increased adherence of T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages.1-3

Vascular endothelium is the principal controller of leukocyte traffic between the bloodstream and the extravascular space.4 In fact, the migration of leukocytes from the blood to sites of extravascular injury is mediated through a sequential cascade of leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesive interactions that involve an array of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) on leukocytes and endothelial cells.4 This multistep process is initiated by the tethering of leukocytes to the endothelium, followed by weak, transient, adhesive interactions manifested as leukocyte rolling, leading ultimately to firm leukocyte adhesion to and subsequent transmigration through the vascular endothelium.5,6 Different CAMs, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and selectins, have all been implicated in atherogenesis.3 In this context, arterial endothelium has been shown to express the same CAMs as those expressed in venular endothelium.7-9 Although leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in postcapillary venules are induced by a wide range of stimuli, arteriolar rolling is only induced by certain risk factors for atherosclerosis, among them perivascular laser injury, treatment with cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and cigarette smoke.10-15 However, to date no mediator has been shown to induce adhesion.

Angiotensin II (Ang II) is the main effector peptide of the renin-angiotensin system, and it has been shown to exert proinflammatory activity. Ang II is capable of promoting monocyte adhesion and activation in vitro.16 This may be directly relevant because hypertension is associated with increased Ang II levels and monocyte migration into the vessel wall, a critical event leading to the development of the atherosclerotic lesion, which can be attenuated by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition or by pretreatment with an Ang II AT1 receptor antagonist.17-19 Moreover, acute Ang II superfusion of the rat mesenteric microcirculation induces leukocyte adhesion, albeit in venules.20 Therefore, some indirect evidence exists that Ang II might be the stimulus for leukocyte adhesion and perhaps subendothelial infiltration observed in hypertension and atherosclerosis.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of Ang II on arteriolar leukocyte adhesion and assessed the molecular mechanisms involved. The observations were compared with leukocyte behavior in venules.

Materials and methods

Materials

Sodium pentobarbital, acetylcholine, Ang II, MOPC 21, and UPC 10 were purchased from Sigma Química (Madrid, Spain). Antibodies used were RMP-1, RP-2, RME-1, TA-2, 5F10, WT-3, and 1A29, which were acquired as previously stated.21-26 Stuf-Mark antigen unmasking fluid, antirat CD3, and antirat ED1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were from Serotec (Madrid, Spain). Conjugated mAb antirat-CD11b-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (OX-42) was purchased from Immunotech (Marseilles, France). DIG gel-shift kit was from Boehringer Mannheim and Enzo Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany). Hybond-N+ was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Europe (Freiburg, Germany). The double-stranded oligonucleotide for NF-κB was from Promega (Madison, WI). Losartan was kindly donated by Merck Sharp & Dohme (Madrid, Spain).

Intravital microscopy

Details of the experimental preparation have been described previously.20 Briefly, male Sprague-Dawley rats, each weighing 200 to 250 g, were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg, intraperitoneally), and the trachea, right jugular vein, and carotid artery were cannulated. After a midline abdominal incision was made, a segment of the midjejunum was exteriorized and placed over an optically clear viewing pedestal maintained at 37°C, which facilitated tissue transillumination. The exposed mesentery was continuously superfused with warmed bicarbonate buffer saline (BBS; pH 7.4) equilibrated with 5% CO2 in nitrogen. An orthostatic microscope (Nikon Optiphot-2, SMZ1) equipped with 20 × objective lens (Nikon SLDW) and 10 × eyepiece permitted tissue visualization. A videocamera (Sony SSC-C350P) mounted on the microscope projected images onto a color monitor (Sony Trinitron PVM-14N2E), and these images were captured on a videotape (Sony SVT-S3000P) for playback analysis (final magnification, × 1300). Arterioles (20- to 30-μm diameter) and single unbranched mesenteric venules (25- to 40-μm diameter) were selected, and the diameters were measured on-line using a video caliper (Microcirculation Research Institute, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX). Centerline red blood cell velocity (Vrbc) was also measured on-line with an optical Doppler velocimeter (Microcirculation Research Institute). Venular blood flow and wall shear rate (γ) were calculated as previously described.27 The number of rolling, adherent, and emigrated leukocytes was determined off-line during playback analysis of videotaped images.

Experimental protocol

Animals were first sedated with ether and later injected intraperitoneally with 5 mL saline or 5 mL Ang II (0.1 or 1 nM) solution. In each experimental group, 4 hours after intraperitoneal injection of the agent under investigation, measurements of venular leukocyte rolling flux, velocity, adhesion, emigration, arteriolar leukocyte adhesion, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), and venular and arteriolar Vrbc, shear rate and diameter were obtained and recorded for 5 minutes. On the basis of these initial experiments, 1 nM Ang II was used for the remainder of the study.

To identify the Ang II receptor involved in arteriolar leukocyte adhesion, a group of animals was injected intravenously with an Ang II AT1 receptor antagonist, losartan (10 mg/kg), 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of Ang II. Another group of animals received intraperitoneal injections of Ang II, and leukocyte responses were evaluated 24 hours later.

To evaluate the effect of leukocyte adhesion on vascular function, acetylcholine 100 μM was superfused to the mesentery for 30 minutes 4 hours after Ang II (1 nM) or buffer intraperitoneal injection. Differences in vessel diameters were determined before and after acetylcholine superfusion, once leukocyte adhesion was patent.

Adhesion molecules involved in Ang II-induced responses after 4 hours of its intraperitoneal administration were determined by pretreatment of the animals with different mAbs directed against rat leukocyte or endothelial CAMs 15 minutes before Ang II injection. Doses used were 2.5 mg/kg for RMP-1 (antirat P-selectin) and RME-1 (antirat E-selectin), 4 mg/kg for TA-2 (antirat α4-integrins), 1 mg/kg for 5F10 (antirat VCAM-1) and WT-3 (antirat β2-integrins), and 2 mg/kg for 1A29 (antirat ICAM-1). All mAbs were intravenously injected through the lateral tail vein. Antibodies doses used completely blocked the function of the different CAMs investigated in previous in vivo studies.28,29 To determine the effect of the antibodies on levels of circulating leukocytes, blood samples were taken from the rats 4 hours after Ang II intraperitoneal injection.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was used to examine expression of the endothelial CAMs P- and E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1. When the experiment using intravital microscopy was completed, the portion exposed to saline or to Ang II for 4 hours was then isolated and further fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 90 minutes at 4°C, as previously described.30 After fixation, the tissue was dehydrated using graded acetone washes at 4°C and embedded in paraffin wax, and 4-μm-thick sections were cut.

Immunohistochemical localization of P-selectin, E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 was accomplished using a modified avidin and biotin immunoperoxidase technique, as previously described by Sanz et al.30 After different previous procedures, tissue sections were incubated with the antirat-P-selectin mAb (RMP-1), antirat-E-selectin mAb (RME-1), antirat-ICAM-1 mAb (1A29), or antirat-VCAM-1 mAb (5F10) for 24 hours at 200 μg/mL. Control preparations consisted of incubations with the isotype-matched murine antibody MOPC 21 (immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]) or UPC 10 (IgG2a) as primary antibodies for the same period of time at 200 μg/mL. Thirty arterioles and venules were examined in each group for each CAM investigated, and the percentage of positive-staining vessels was determined. Positive staining was defined as an arteriole or a venule displaying brown reaction product.

To elucidate the type of leukocyte that adhered to the endothelia of arterioles and venules exposed to Ang II for 4 hours, some sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The phenotype of the cells attached to the arterial endothelium after 4-hour Ang II intraperitoneal injection was further investigated by immunohistochemical studies. Tissue sections were incubated with an antirat CD3 mAb that reacts with an epitope of CD3 expressed in rat T cells or with a specific monocyte/macrophage marker, an antirat ED1 antibody.

Determining NF-κB binding activity

The procedure followed was similar to that previously used.31 Nuclear protein extracts were prepared from the mesenteric tissue exposed to buffer or Ang II for 4 hours. Protein quantification was performed using the Bradford assay. Aliquots of nuclear extracts with equal amounts of protein (10 μg) were processed using the DIG gel-shift kit according to manufacturer's instructions, and binding reactions were started by the addition of 30 fmol double-stranded digoxigenin-labeled oligonucleotide for NF-κB (sense-strand sequence is 5′-AGT TGA GGGGACTTTCCC AGG C-3′; the underlined sequence corresponds to a κB-binding motif). Samples were analyzed on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoretic transfer to nylon membrane (Hybond-N+), complexes were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection system. The image analysis system AnalySISÒ, version 3.0 (Soft Imaging System, Münster, Germany) was used to quantify band intensity. To ascertain the specificity of the binding reaction, competition assays were performed in the presence of 100-fold excess (3000 fmol) unlabeled oligonucleotide.

Determining surface expression of αMβ2 integrins

Expression of αMβ2 integrins was determined in rat leukocytes from peripheral blood and peritoneal cavity. Animals were sedated with ether and injected intraperitoneally with 5 mL saline or 5 mL solution of 1 nM Ang II. In each experimental group, 4 hours after intraperitoneal injection of the agent under investigation, animals were again sedated with ether, blood samples were obtained by cardiac puncture, and the peritoneal cavity was lavaged with 30 mL heparinized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 U/mL). Duplicate samples (100 μL) of citrated whole blood or a suspension of peritoneal leukocytes (2.5 × 106 cells/mL) were then incubated with saturating amounts (10 μL) of the conjugated mAb antirat-αMβ2-FITC for 20 minutes on ice in the dark. We performed an automated lysing procedure using an EPICS Q-PREP system (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL) to remove red blood cells and to fix leukocytes.

Flow cytometry

All analyses were performed using an EPICS XL-MCL Flow Cytometer (Coulter Electronics), as described previously.20 Surface antigen expression (FITC-fluorescence) was analyzed separately in granulocytes and monocytes identified by their specific features of size (forward-angle light scatter [FS]) and granularity (side-angle light scatter [SS]) in the flow cytometer.

Statistical analysis

All values are reported as mean ± SEM. Data within groups were compared using analysis of variance (1-way ANOVA) with Newman-Keuls post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at P values of less than .05.

Results

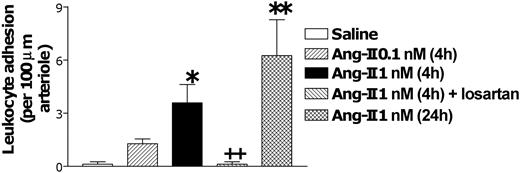

Intravital microscopy was used to examine leukocyte trafficking in the Ang II-treated rat mesentery for 4 hours. Figure 1 demonstrates that exposure to Ang II at 1 nM, but not at 0.1 nM, for this time period induced a significant enhancement of arteriolar leukocyte adhesion without causing changes in the arteriolar diameter (23.4 ± 2.3 vs 23.6 ± 1.9 μm) or shear rate (1019 ± 71.7 vs 1213.9 ± 147.5 s-1) when compared with values in saline-injected animals for 4 hours. Interestingly, this effect was not detected after 1-hour superfusion with the same dose of Ang II.20 In this vascular bed, any cell that tethered to the endothelium immediately adhered without notable rolling. Administering losartan before 1 nM injection of Ang II resulted in the total abolition of this response. Moreover, when arteriolar endothelium was exposed to Ang II for 24 hours, a greater increase in this parameter than that found at 4 hours was observed (Figures 1, 3G). Furthermore, superfusing the mesentery with acetylcholine for 30 minutes after 4-hour saline administration resulted in an increase of the arteriolar diameter (2.5 ± 0.4 μm). In contrast, exposing the tissue for 30 minutes to acetylcholine after 4-hour Ang II injection, once the leukocytes clearly adhered to the arteriolar endothelium, caused significantly less vasodilatation than that encountered in saline-treated animals (0.7 ± 0.2 μm; P < .01).

Effect of Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric arterioles. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6), 0.1 nM Ang II (n = 5), or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). Four hours later arteriolar leukocyte adhesion was quantified. A group of animals was pretreated with losartan (n = 5) 15 minutes before intraperitoneal injections of 1 nM Ang II, and responses were evaluated 4 hours later. A final group was intraperitoneally treated with 1 nM Ang II, and 24 hours later arteriolar leukocyte adhesion was determined. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 and **P < .01 relative to the saline group. ++P < .01 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

Effect of Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric arterioles. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6), 0.1 nM Ang II (n = 5), or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). Four hours later arteriolar leukocyte adhesion was quantified. A group of animals was pretreated with losartan (n = 5) 15 minutes before intraperitoneal injections of 1 nM Ang II, and responses were evaluated 4 hours later. A final group was intraperitoneally treated with 1 nM Ang II, and 24 hours later arteriolar leukocyte adhesion was determined. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 and **P < .01 relative to the saline group. ++P < .01 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

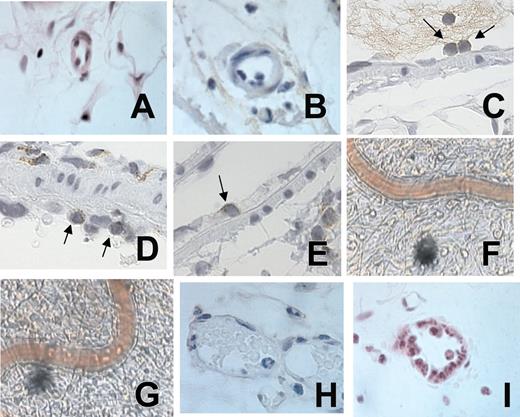

Representative photomicrographs of rat mesenteric arterioles and venules in animals untreated and treated with Ang II. Arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour saline (A) or Ang II (B) exposure. CD3+ staining of leukocytes adhered to the arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour Ang II exposure (C). ED1-positive staining of leukocytes adhered to the arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour Ang II exposure (D). ED1-positive staining of a leukocyte emigrating through the arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour Ang II exposure (E). Video photomicrographs of the rat mesenteric arterioles after 24-hour buffer intraperitoneal injection (F). Video photomicrographs of the rat mesenteric arterioles after 24-hour Ang II intraperitoneal injection (G). Venular endothelium after 4-hour saline (H) or Ang II exposure (I). A 100×/1.25 oil objective lens was used for panels A-E and H-I; a 20×/0.40 objective lens was used for panels F-G. Panels A, B, H, and I were stained with hematoxylin/eosin, and panels C, D, and E were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin. Leica IM1000 software capture imaging (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to obtain the images in panels A-E and H-I, and a Sony color video printer was used for the images in panels F and G.

Representative photomicrographs of rat mesenteric arterioles and venules in animals untreated and treated with Ang II. Arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour saline (A) or Ang II (B) exposure. CD3+ staining of leukocytes adhered to the arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour Ang II exposure (C). ED1-positive staining of leukocytes adhered to the arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour Ang II exposure (D). ED1-positive staining of a leukocyte emigrating through the arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour Ang II exposure (E). Video photomicrographs of the rat mesenteric arterioles after 24-hour buffer intraperitoneal injection (F). Video photomicrographs of the rat mesenteric arterioles after 24-hour Ang II intraperitoneal injection (G). Venular endothelium after 4-hour saline (H) or Ang II exposure (I). A 100×/1.25 oil objective lens was used for panels A-E and H-I; a 20×/0.40 objective lens was used for panels F-G. Panels A, B, H, and I were stained with hematoxylin/eosin, and panels C, D, and E were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin. Leica IM1000 software capture imaging (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to obtain the images in panels A-E and H-I, and a Sony color video printer was used for the images in panels F and G.

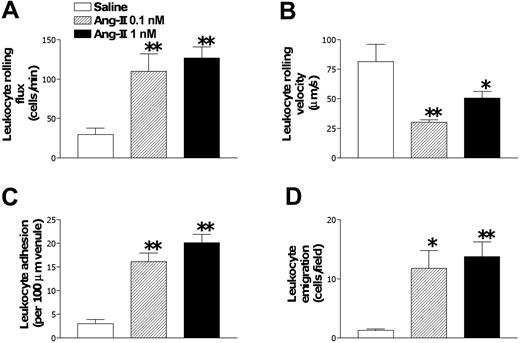

In postcapillary venules, Ang II injections at 1 and 0.1 nM for 4 hours presented significant increases in venular leukocyte rolling flux, adhesion, and emigration and concomitant decreases in venular leukocyte rolling velocity (Figure 2). Administering 1 nM Ang II did not modify systemic leukocyte counts (9.5 ± 1.288 vs 8.366 ± 0.558 × 109/L [9500.0 ± 1288.4 vs 8366.7 ± 558.4 cells/μL]), MABPs (108.9 ± 16.6 vs 100.3 ± 14.8 mm Hg), venular diameters (29.2 ± 2.9 vs 28.4 ± 2.6 μm), or venular shear rates (461.4 ± 87.0 vs 774.3 ± 181.7 s-1) when compared with values in saline-injected animals for 4 hours. Furthermore, exposing the tissue for 30 minutes to acetylcholine after 4-hour Ang II or buffer injection did not cause significant changes in venular diameters (0.5 ± 0.2 and 0.5 ± 0.3 μm, respectively). Given that arteriolar leukocyte adhesion was only detected when Ang II was administered at 1 nM, this dose was used for the remainder of the study.

Subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric postcapillary venules. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6), 0.1 nM (n = 5), or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). Four hours later, responses of leukocyte rolling flux (A), leukocyte rolling velocity (B), leukocyte adhesion (C), and leukocyte emigration (D) were quantified. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 and **P < .01 relative to the saline group.

Subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric postcapillary venules. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6), 0.1 nM (n = 5), or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). Four hours later, responses of leukocyte rolling flux (A), leukocyte rolling velocity (B), leukocyte adhesion (C), and leukocyte emigration (D) were quantified. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 and **P < .01 relative to the saline group.

Histologic examination was carried out in the exposed tissue to determine the type of leukocytes recruited by Ang II (Figure 3). Lymphocytes and monocytes were the predominant cells adherent on the arteriolar endothelium after 4-hour exposure to Ang II (Figure 3B-D). Interestingly, at this time, some leukocytes were emigrating through the arteriolar endothelium (Figure 3E). By contrast, within the postcapillary venules, most of the adherent leukocytes on the vascular wall were neutrophils (Figure 3I).

NF-κB DNA-binding activity was significantly increased at 4 hours after Ang II intraperitoneal injection in the exposed tissue. Ang II caused a 1.7 ± 0.2-fold increase compared with saline-injected animals for the same period of time (n = 5; P < .01).

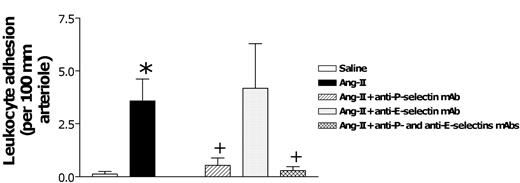

Once this model was established, we next examined the adhesive mechanism underlying Ang II-induced arteriolar leukocyte adhesion and leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in post-capillary venules. Figure 4 summarizes the role of P- and E-selectin on Ang II-induced arteriolar leukocyte adhesion. Although administering the blocking anti-P-selectin mAb (RMP-1) reduced the adhesion response by 88% in arterioles, the antibody against E-selectin function (RME-1) had no effect. In contrast, combined treatment with antibodies against P-selectin (RMP-1) and E-selectin (RME-1) reduced Ang II-induced arteriolar adhesion to basal levels (Figure 4).

Effects of anti-P-selectin and anti-E-selectin mAbs on subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric arterioles. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6) or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). In further groups of animals, 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of 1 nM Ang II, rats were treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (n = 5), anti-E-selectin mAb (n = 5), or a combination of both (n = 4). Four hours later, arteriolar leukocyte adhesion responses were quantified. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 relative to the saline group. +P < .05 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

Effects of anti-P-selectin and anti-E-selectin mAbs on subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric arterioles. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6) or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). In further groups of animals, 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of 1 nM Ang II, rats were treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (n = 5), anti-E-selectin mAb (n = 5), or a combination of both (n = 4). Four hours later, arteriolar leukocyte adhesion responses were quantified. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 relative to the saline group. +P < .05 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

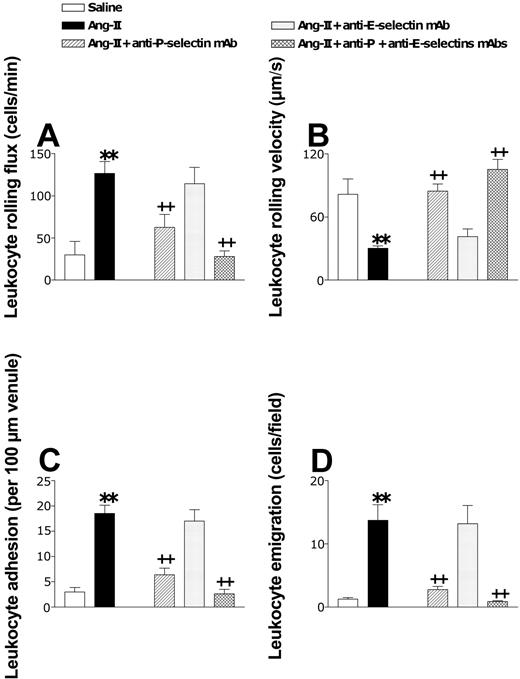

In the postcapillary venules, Ang II-induced leukocyte rolling flux, adhesion, and emigration were inhibited by 66%, 78%, and 88%, respectively, when animals were pretreated with the function-blocking anti-P-selectin mAb (RMP-1) (Figure 5). As found in the arteriolar endothelium exposed to Ang II, administering a neutralizing mAb against E-selectin (RME-1) did not modify Ang II-induced leukocyte responses. Combining these 2 mAbs reduced all these parameters to baseline levels (Figure 5). In addition, the reduction in venular leukocyte rolling velocity induced by this peptide was also reversed by a function-blocking mAb against P-selectin and by a combination of these 2 mAbs directed against both selectins (Figure 5B).

Effects of anti-P-selectin and anti-E-selectin mAbs on subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric postcapillary venules. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6) or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). In other groups of animals, 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of 1 nM Ang II, rats were treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (n = 5), anti-E-selectin mAb (n = 5), or a combination of both (n = 4). Four hours later, responses of leukocyte rolling flux (A), leukocyte rolling velocity (B), leukocyte adhesion (C), and leukocyte emigration (D) were quantified. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. **P < .01 relative to the saline group. ++P < .01 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

Effects of anti-P-selectin and anti-E-selectin mAbs on subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric postcapillary venules. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6) or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). In other groups of animals, 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of 1 nM Ang II, rats were treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (n = 5), anti-E-selectin mAb (n = 5), or a combination of both (n = 4). Four hours later, responses of leukocyte rolling flux (A), leukocyte rolling velocity (B), leukocyte adhesion (C), and leukocyte emigration (D) were quantified. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. **P < .01 relative to the saline group. ++P < .01 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

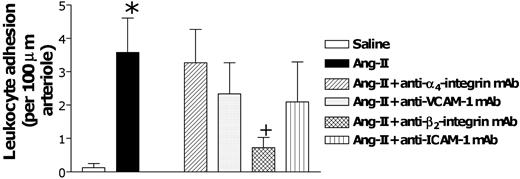

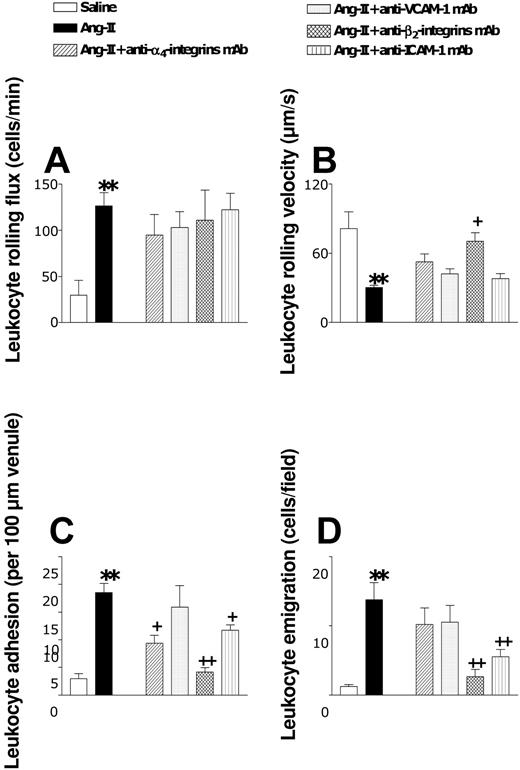

We next examined the involvement of α4- and β2-integrins and of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1. Animals were pretreated with function-blocking antibodies directed against these CAMs before Ang II intraperitoneal injection. Only β2-integrin blockade was able to reduce (83%) the arteriolar leukocyte adhesion elicited by this peptide (Figure 6). In postcapillary venules, none of these treatments affected the increase in leukocyte rolling flux elicited by Ang II (Figure 7A). However, Ang II-induced increases in venular leukocyte adhesion were significantly diminished by pretreatment of the animals with mAbs directed against α4- and β2-integrins and against ICAM-1 (Figure 7C). Leukocyte emigration in this vascular bed was only affected when the function of the β2-integrins or ICAM-1 was blocked (Figure 7D). The lack of effect of VCAM-1 function on the leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions induced by Ang II (Figure 7) was significant.

Effects of anti-α4-integrin, anti-VCAM-1, anti-β2-integrin, and anti-ICAM-1 mAbs on subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric arterioles. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6) or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). In other groups of animals, 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of 1 nM Ang II, rats were treated with anti-α4-integrin mAb (n = 5), anti-VCAM-1 mAb (n = 4), anti-β2-integrin mAb (n = 5), or anti-ICAM-1 mAb (n = 5). Four hours later, arteriolar leukocyte adhesion responses were quantified. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 relative to the saline group. +P < .05 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

Effects of anti-α4-integrin, anti-VCAM-1, anti-β2-integrin, and anti-ICAM-1 mAbs on subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric arterioles. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6) or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). In other groups of animals, 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of 1 nM Ang II, rats were treated with anti-α4-integrin mAb (n = 5), anti-VCAM-1 mAb (n = 4), anti-β2-integrin mAb (n = 5), or anti-ICAM-1 mAb (n = 5). Four hours later, arteriolar leukocyte adhesion responses were quantified. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 relative to the saline group. +P < .05 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

Effects of anti-α4-integrin, anti-VCAM-1, anti-β2-integrin, and anti-ICAM-1 mAbs on subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric postcapillary venules. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6) or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). In other groups of animals, 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of 1 nM Ang II, rats were treated with anti-α4-integrin mAb (n = 5), anti-VCAM-1 mAb (n = 4), anti-β2-integrin mAb (n = 5), or anti-ICAM-1 mAb (n = 5). Four hours later, responses were quantified for leukocyte rolling flux (A), leukocyte rolling velocity (B), leukocyte adhesion (C), and leukocyte emigration (D). Results are represented as mean ± SEM. **P < .01 relative to the saline group. +P < .05 and ++P < .01 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

Effects of anti-α4-integrin, anti-VCAM-1, anti-β2-integrin, and anti-ICAM-1 mAbs on subacute (4-hour) Ang II-induced leukocyte responses within rat mesenteric postcapillary venules. Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline (n = 6) or 1 nM Ang II (n = 6). In other groups of animals, 15 minutes before intraperitoneal administration of 1 nM Ang II, rats were treated with anti-α4-integrin mAb (n = 5), anti-VCAM-1 mAb (n = 4), anti-β2-integrin mAb (n = 5), or anti-ICAM-1 mAb (n = 5). Four hours later, responses were quantified for leukocyte rolling flux (A), leukocyte rolling velocity (B), leukocyte adhesion (C), and leukocyte emigration (D). Results are represented as mean ± SEM. **P < .01 relative to the saline group. +P < .05 and ++P < .01 relative to the 1 nM Ang II group.

Immunohistochemical studies revealed that when the mesenteric tissue was subjected to 4-hour saline exposure, almost no arterioles stained positively for P-selectin, E-selectin, and VCAM-1 (Table 1). In contrast, ICAM-1 was present in moderate amounts. In the arteriolar endothelium, after 4-hour Ang II exposure, P-selectin and VCAM-1 were clearly up-regulated, ICAM-1 expression was increased, and E-selectin was weakly though significantly up-regulated (Table 1). The percentage of postcapillary venules staining positively for P-selectin, E-selectin, and VCAM-1 in saline-treated animals was consistently low, but constitutive expression of ICAM-1 was found (Table 1). Ang II exposure for 4 hours increased P-selectin, E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 expression in this vascular bed (Table 1).

Effect of 1-nM Ang II intraperitoneal injection on P-selectin, E-selectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 expression in the rat mesenteric arterioles and postcapillary venules

. | Arteriole, % . | . | Venule, % . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAM . | Saline . | Ang II . | Saline . | Ang II . | ||

| P-selectin | 6.7 ± 4.2 | 66.7 ± 6.7* | 10.0 ± 4.5 | 70.0 ± 11.3* | ||

| E-selectin | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 23.3 ± 6.1† | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 36.7 ± 6.1* | ||

| VCAM-1 | 6.7 ± 4.2 | 56.7 ± 12.0* | 6.7 ± 4.2 | 63.3 ± 6.1* | ||

| ICAM-1 | 26.7 ± 4.2 | 50.0 ± 8.5† | 40.0 ± 7.3 | 63.3 ± 14.6† | ||

. | Arteriole, % . | . | Venule, % . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAM . | Saline . | Ang II . | Saline . | Ang II . | ||

| P-selectin | 6.7 ± 4.2 | 66.7 ± 6.7* | 10.0 ± 4.5 | 70.0 ± 11.3* | ||

| E-selectin | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 23.3 ± 6.1† | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 36.7 ± 6.1* | ||

| VCAM-1 | 6.7 ± 4.2 | 56.7 ± 12.0* | 6.7 ± 4.2 | 63.3 ± 6.1* | ||

| ICAM-1 | 26.7 ± 4.2 | 50.0 ± 8.5† | 40.0 ± 7.3 | 63.3 ± 14.6† | ||

Rats were treated intraperitoneally with saline or 1 nM Ang II. Four hours later, the exposed mesentery was isolated and further fixed in paraformaldehyde. Immunohistochemical localization of P-selectin, E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 was accomplished using a modified avidin and biotin immunoperoxidase technique. Positive staining was defined as an arteriole or a venule displaying brown reaction product. Results are representative of 6 experiments for each treatment and are expressed as percentages of CAM expression (mean ± SEM).

P < .01.

P < .05 relative to the saline group.

In vitro it was demonstrated that direct stimulation of peripheral leukocytes with Ang II did not result in increased αMβ2-integrin expression20 ; however, a significant decrease in Ang II-induced arteriolar and venular leukocyte adhesion was observed when animals were pretreated with an mAb against β2-integrins. Therefore, we wanted to investigate whether leukocytes that had emigrated in response to this peptide had increased expression of the αMβ2-integrin. We observed that though intraperitoneal injection of Ang II did not affect the expression of αMβ2-integrins in rat peripheral blood neutrophils or monocytes, a significant increase in the expression of this leukocyte CAM was detected in both leukocyte subsets once they emigrated to the peritoneal cavity (rat monocytes, 112.2 ± 10.3 vs 141.9 ± 4.5 mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]; P < .01) (rat neutrophils, 215.0 ± 18.8 vs 414.5 ± 64.0 MFI; P < .01).

Discussion

Leukocyte recruitment to the arterial wall is important in pathophysiologic states such as atherosclerosis and hypertension, where Ang II seems to play a critical role.17,18 Leukocyte-endothelium interactions are generally observed in postcapillary venules but are rarely observed in arterioles of tissues prepared for intravital microscopy. The present study shows, for the first time, that 4-hour exposure to Ang II at subvasoconstrictor and physiologically relevant doses (1 nM) causes arteriolar leukocyte adhesion in vivo in the rat mesenteric microcirculation, and this effect is mediated through interaction with its AT1 receptor subtype. Interestingly, we did not observe this effect under acute (1-hour) stimulation with Ang II.20 It was necessary to stimulate the mesenteric arterioles with Ang II for several hours so as to obtain a significant enhancement of this parameter. Furthermore, mononuclear cells were found to be the primary cells attached to the arteriolar endothelium when it was stimulated with Ang II for 4 hours, together with the endothelial infiltration of some of these cells. A further increase in arteriolar leukocyte adhesion was encountered after 24-hour exposure to the peptide. Additionally, when leukocytes adhered to the arteriolar wall after Ang II exposure, a clear impairment in endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine was also detected. Thus, the finding that mononuclear leukocytes adhered to these microvessels after Ang II stimulation may have relevance regarding inappropriate monocyte adhesion in vascular abnormalities that adversely affect arteriolar function. Indeed, we hypothesize that this observation could be extrapolated to other vascular territories that are prone to the development of atherosclerotic lesions, including sites of low or fluctuating shear, such as coronary arteries, curvatures, or branch points. These findings provide evidence of a causal link between this peptide hormone and the onset of mononuclear leukocyte adhesion, perhaps in pathophysiologic conditions in which Ang II plasma levels can be rapidly elevated and maintained for extended times. Therefore, Ang II may be critical for the onset and progression of atherosclerotic lesions. Nevertheless, its role in chronic conditions and in different species remains a subject for future studies.

Once it was established that NF-κB activation was implicated in the leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions induced by 4-hour stimulation with Ang II, we studied the CAMs involved in these responses. Selectins mediate the primary interaction between the leukocytes and the endothelium.5,6 In the present study, we found that P-selectin mediates the arteriolar leukocyte adhesion elicited by Ang II and that P- and E-selectin were significantly up-regulated in the arteriolar endothelium. To our knowledge, this is the first report that involves P-selectin in the arteriolar leukocyte adhesion caused by this peptide hormone. In vitro, Gräfe et al32 could only find a role for E-selectin in Ang II-induced leukocyte responses in the arterial endothelium, which might be explained by the inability of cultured endothelial cells to express P-selectin after several passages.33 Selectins mediate the initial tethering and the subsequent rolling of leukocytes. However, rolling leukocytes were not observed at the arteriolar level after 4-hour Ang II stimulation. The absence of this leukocyte-endothelial cell interaction in mesenteric arterioles might be explained by the fact that integrins on mononuclear leukocytes are rapidly activated, causing immediate adhesion. In this context, Luscinskas et al34 found that monocytes in vitro do not roll but rapidly adhere, albeit to venular endothelial cells, after stimulation with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).

The delayed leukocyte adhesion encountered in arterioles compared with that found in venules in response to Ang II may be caused by different activation mechanisms. In postcapillary venules, the early response of neutrophil accumulation is primarily mediated by the direct effect of Ang II on endothelial cells through the expression of P-selectin.20 In arterioles, leukocyte adhesion perhaps requires the additional release of other inflammatory mediators. One possible candidate may be interleukin-4 (IL-4). Ang II receptors are present on mononuclear cells,35 and it can promote their activation.16 Activated mononuclear cells may produce different cytokines, such as IL-4, which increases P-selectin expression through a transcriptionally dependent mechanism with kinetics that are delayed compared with the action of other cytokines, such as TNF-α.36 In addition, IL-4 can cause eosinophils and mononuclear cells, but not neutrophils, to adhere to the endothelium37,38 and CC-chemokines such as MCP-1 and MCP-4 to be released, resulting in the selective accumulation of mononuclear cells39,40 even though P-selectin is up-regulated.

In the sequential adhesive cascade that mediates the trafficking of leukocytes from blood to sites of inflammation, leukocytes must adhere firmly to the endothelium before transmigrating. Leukocyte activation precedes firm adhesion and is mediated by previous interactions of leukocytes with selectins and chemoattractants.5,6 Two types of integrins are involved in this process—β2-integrins and α4-integrins. In this study a significant decrease in Ang II-induced leukocyte adhesion in arterioles and postcapillary venules was observed after administration of an anti-β2-integrin mAb, a finding not previously reported. Although direct Ang II stimulation caused no changes in β2-integrin expression on the leukocyte surface,20 it is possible that Ang II promoted β2-integrin activation. In addition, this peptide hormone can elicit the release of endogenously generated chemotactic mediators that may be implicated in this interaction, increasing the expression of these CAMs.41-44 Other leukocyte subtypes are recruited in response to Ang II in arterioles and postcapillary venules, suggesting differences in the activation mechanisms and in the chemoattractants released by the 2 endothelia, a finding that our group is now investigating. Nonselective chemoattractants such as platelet-activating factor (PAF) and leukotriene B4 (LTB4) have been implicated in the venular leukocyte recruitment elicited by Ang II,44 which might explain the neutrophil accumulation elicited by this peptide hormone in this vascular bed. Conversely, in response to Ang II, mRNA for MCP-1 is preferentially expressed in arteries.18 Recently, it was demonstrated that blocking the MCP-1 pathway limits Ang II-induced progression of atherosclerotic lesions in hypercholesterolemic mice and reduces gene expression of RANTES and various CC-chemokine receptors in the mouse aorta.45 Therefore, Ang II-induced MCP-1 release might account for the ability of mononuclear leukocytes to activate and selectively adhere to the arterial vessels. The main endothelial ligand for β2-integrins is ICAM-1, and increased ICAM-1 expression in response to Ang II has been described in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs).46 In this work, pretreatment with an anti-ICAM-1 mAb did not affect the arteriolar leukocyte adhesion induced by Ang II but partially reduced the leukocyte adhesion encountered in postcapillary venules. These results suggest the involvement of a non-ICAM-1 endothelial cell ligand or ligands for β2-integrins, such as ICAM-2 or fibrinogen.5,6,47

α4-integrins play an important role in leukocyte adhesion to the vascular endothelium. In the present study, however, Ang II-induced arteriolar leukocyte adhesion was not affected by functional blockade of this CAM, despite mononuclear leukocytes being the predominant cells attached to these vessels. In contrast, a clear role for α4-integrins was observed in the leukocyte adhesion to postcapillary venules elicited by this peptide, despite neutrophils being the primary cells recruited in these vessels. Conversely to expression in humans, rat neutrophils do express functional α4- and β1-integrins,48 which might explain this observation. VCAM-1 is thought to be the primary ligand for α4-integrin, and its up-regulation by Ang II has been clearly demonstrated in the present study and in previous studies.49 However, pretreating the animals with an anti-VCAM-1 mAb did not affect the leukocyte responses elicited by Ang II. Because it was used at higher doses than those necessary to completely block its function,29 these observations raise the possibility that, in this case, increased VCAM-1 expression does not correlate with a functional role for this CAM, as reported by other investigators with other stimuli.50 This suggests the existence of functionally important alternative α4-integrin ligands in mediating Ang II-induced leukocyte accumulation in vivo. In fact, a number of other potential ligands of α4-integrin other than VCAM-1 have been shown to bind to this integrin, such as mucosal addressin MadCAM-1, CS-1 domain of fibronectin, and the matrix protein osteopontin.51-53

Finally, leukocytes migrate through the endothelium in arteries and localize subendothelially. However, the use of intravital microscopy did not allow us to distinguish whether the cells were attached to the arteriolar endothelium or whether they had already emigrated and localized under the intima. Histologic examination of the tissue after 4-hour exposure to Ang II revealed that some mononuclear cells infiltrated the arterioles and emigrated through the endothelium. Nevertheless, Ang II-induced leukocyte emigration was clearly observed in postcapillary venules after 4-hour exposure to the peptide. This effect was partially mediated through β2-integrin-ICAM-1 interaction because the administration of mAbs directed against these CAMs significantly reduced this leukocyte response. Furthermore, leukocytes that emigrated to the peritoneal cavity in response to Ang II clearly presented up-regulation of this β2-integrin.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated here for the first time in vivo that Ang II induces arteriolar leukocyte adhesion within 4 hours at subvasoconstrictor and physiologically relevant doses. Hence, Ang II may play a critical role in primary leukocyte attachment to the arterial wall. This effect primarily depends on increased P-selectin and β2-integrin expression. It may be a key to understanding mononuclear leukocyte adhesion in human vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and may implicate Ang II in the onset of this process.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 25, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2974.

Supported by grants PM 98-205 and SAF 2002-01482 from CICYT, Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia, by grant MT-7684 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (A.C.I.), and by a grant from the Spanish Ministerio de Educacion, Cultura y Deporte (Y.N.A.N., M.M.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal