Abstract

Efforts to change the fate of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and progenitor cells (HPCs) in vitro have met with limited success. We hypothesized that previously utilized in vitro conditions might result in silencing of genes required for the maintenance of primitive HSCs/HPCs. DNA methylation and histone deacetylation are components of an epigenetic program that regulates gene expression. Using pharmacologic agents in vitro that might possibly interfere with DNA methylation and histone deacetylation, we attempted to maintain and expand cells with phenotypic and functional characteristics of primitive HSCs/HPCs. Human marrow CD34+ cells were exposed to a cytokine cocktail favoring differentiation in combination with 5aza 2′deoxycytidine (5azaD) and trichostatin A (TSA), resulting in a significant expansion of a subset of CD34+ cells that possessed phenotypic properties as well as the proliferative potential characteristic of primitive HSCs/HPCs. In addition, 5azaD- and TSA-pretreated cells but not the CD34+ cells exposed to cytokines alone retained the ability to repopulate immunodeficient mice. Our findings demonstrate that 5azaD and TSA can be used to alter the fate of primitive HSCs/HPCs during in vitro culture.

Introduction

Modifications of chromatin such as DNA methylation and histone acetylation are important for regulating gene function.1-4 Silencing of genes has been shown to be accompanied by DNA methylation of a gene's promoter and by histone deacetylation in the region containing the genes of interest with inhibition of DNA methylation or histone deacetylation reversing the silencing effect. Specific patterns of DNA methylation of genes and histone acetylation are known to be associated with transcriptional regulation and modification of chromatin structure.5 Histone acetylation has also been shown to have a profound effect on the normal transition from a fetal to an adult hematopoietic cellular differentiation program during ontogeny.6 Numerous reports have shown that the proliferative and self-renewal capacity of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and progenitor cells (HPCs) decreases progressively with differentiation, resulting in cells belonging to specific multiple hematopoietic lineages.7,8 There is evidence that early HSCs express a promiscuous set of transcription factors and an open chromatin structure required to maintain their multipotentiality, which is progressively quenched as these cells progress down a particular pathway of differentiation.9 The mechanisms that govern these stem cell fate decisions are likely under tight control but remain potentially alterable. Although the global gene expression profiles for HSCs have recently been described, very little is known about the dynamics of gene expression necessary for HSC fate decisions.10-12 We hypothesized that these processes associated with differentiation may be mediated by DNA methylation and histone deacetylation allowing stable silencing of a large fraction of the genome, thus causing the transcriptional machinery to focus on those genes essential for the expression and maintenance of the differentiated phenotype.2,13

5azacytidine and its analogs as well as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs) each have dramatic effects on transcriptional regulation.1-4 These 2 classes of drugs in combination may be capable of synergistically reactivating developmentally silenced genes.13-15 HSCs are quiescent cells that are capable of exiting G0/G1 following exposure to early acting cytokines including stem cell factor (SCF), FLT-3 ligand, and thrombopoeitin (TPO).16,17 There has been very limited success in controlling this process of HSC commitment and differentiation in vitro beyond HSCs undergoing a limited number of cell divisions.18,19 We have developed a model system to assess the role of 5aza 2′deoxycytidine (5azaD) and trichostatin A (TSA) in modifying HSC/HPC fate decisions.

Materials and methods

Isolation of human CD34+ cells

Cryopreserved cadaveric adult human bone marrow (BM) mononuclear cells (MNCs) were rapidly thawed at 37°C and slowly diluted dropwise in RMPI (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, MD) containing 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and 0.1 mg/mL Dnase I (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) before further purification, and left to stand for 45 minutes at room temperature.

In other experiments, fresh mononuclear cells, isolated from bone marrow aspirated from healthy human volunteers after informed consent was obtained according to the guidelines of the institutional review board of the University of Illinois at Chicago, were utilized. CD34+ cells were immunomagentically enriched using a magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) CD34+ isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the MNCs were washed and resuspended in Ca++-free and Mg++-free Dulbecco modified phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; Biowhittaker) supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and 2 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA). Cells were incubated with hapten-labeled anti-CD34+ monoclonal antibody (mAb; QBEND-10; Miltenyi Biotec) in the presence of Fc blocking reagent, and then with anti-hapten coupled to microbeads. Labeled cells were filtered through a 30-μm nylon mesh and separated using a high-gradient magnetic separation column. Magnetically retained cells were then flushed out and used for the experiments. These cells were eluted and stained using a mAb against a different epitope of CD34 (HPCA 2) to determine the purity of CD34+ cell–enriched BM and analyzed for phenotype and purity using flow cytometric methods (see “Phenotypic analysis by flow cytometry”). The purity of the CD34+ populations routinely was 90% ± 2.3%.

Ex vivo cultures

To promote cell division of isolated CD34+ cells, a stroma-free suspension culture was established as previously described.20 Tissue-culture dishes (35 mm; Costar, Corning, NY) were initially seeded with 1 × 105 CD34+ cells/well in 2.5 mL Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; Biowhittaker) containing 30% FBS and a cocktail of cytokines specifically thought to promote exit from G0/G1 in primitive HSC populations that consisted of 100 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL FLT-3 ligand, 100 ng/mL TPO, and 50 ng/mL interleukin 3 (IL-3) (all were gifts from Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA). Cells were maintained in the media and incubated at 37° C in a 100%-humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48 hours. After an initial 16 hours of incubation, cells were then exposed to the demethylating agent 5azaD (Sigma) at a concentration of 10-6 M. After 48 hours, cells were washed and then equally distributed to new tissue-culture dishes in 2.5 mL IMDM supplemented with 30% FBS containing cytokines known to promote terminal differentiation of HSCs into multiple hematopoietic lineages. The cocktail of cytokines consisted of 100 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL granulocytemonocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), 50 ng/mL IL-3, 50 ng/mL IL-6, and 5 U/mL recombinant erythropoietin (EPO; Amgen). Cells at this time point were exposed to TSA (Sigma) at 5 ng/mL and the culture was continued for an additional 7 days. At the end of the culture period viable cells were enumerated using the trypan blue exclusion method. In other studies, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; Sigma) was used at a concentration of 200 μg/mL and added at the 16-hour time point instead of 5azaD and the cultures carried on as described previously in this paragraph without the addition of TSA. In additional experiments, primary marrow CD34+CD90+ cells were isolated using mAb staining and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) with a FACSVantage (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and treated with 5azaD and TSA to examine whether the effect of these agents is directed to a purified HSC population.

Combined bisulfite restriction analysis (COBRA) assay and bisulfite sequence analysis

DNA was prepared from cultured CD34+ cells (0.5-2.0 × 106 total cells) using the QIAamp DNA blood Minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. The purified DNA was digested with 10 to 20 units HindIII at 37° C for 1 hour followed by 2 extractions with a 50:50:1 mixture of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol saturated with 0.5 M Tris, pH 7.5. The digested DNA was precipitated overnight at -20° C in the presence of 2.5 volumes ethanol and 0.3 M sodium acetate, pH 7.0. DNA was harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in 70% ethanol, and dissolved in H2O. Denaturation was performed by incubation of 1 to 2 μg DNA in 10 to 20 μL 0.3 M NaOH at 37° C for 20 minutes. Bisulfite modification was performed by the addition of 200 μL bisulfite solution (2.5 M sodium metabisulfite, 140 mM hydroquinone) prepared according to the method as described,21-23 followed by incubation for 4 hours at 50° C. The bisulfite-modified DNA was purified using the Wizard DNA Clean up System (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Desulphonation was performed by the addition of one-tenth volume 3 M NaOH followed by incubation at 37° C for 20 minutes. The desulphonated DNA was precipitated in the presence of 2.5 volumes ethanol; 0.3 M Na acetate; and 20 μg glycogen at -20° C overnight. For COBRA (combined bisulfite restriction analysis), a 201-bp fragment of the γ-globin promoter region was amplified by 2 rounds of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using doubly nested primers. Primers for the first round of amplification were AAAAGAAGTTTTGGTATTTTTTATGATGGG (30-mer; sense) and TCCTCCAACATCTTCCACATTCACCTTAC (29-mer; antisense). Primers for the second round were TGGGAGAAGAAAATTAGTTAAAGGG (25-mer;sense) and AATCAAAACAAAACTAACCAACCC (24-mer; antisense). PCR was performed using hot-start conditions according to the following scheme: 2 cycles at 94° C for 2 minutes, 50° C for 3 minutes, 72° C for 2 minutes; 33 cycles at 94° C for 2 minutes, 50° C for 2 minutes, 72° C for 2 minutes; 1 cycle at 94° C for 2 minutes, 50° C for 2 minutes, 72° C for 7 minutes. PCR product (5-10 μL) was digested with 10 to 20 units Hinf1 at 37° C for 2 hours. The PCR product is cleaved by Hinf1 into 2 fragments of 56 bp and 145 bp only if the CpG residue at -256 is methylated in the original DNA sample. Digested products were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (5% gel), visualized by staining with ethidium bromide, and quantified by densitometry. Methylation of the ϵ- and γ-globin promoters was measured by bisulphite sequence analysis. Following bisulfite modification, a γ-globin promoter fragment containing 5 CpG residues at -54, -51, +5, +16, and +48 was amplified using nested PCR. An additional fragment containing 3 CpG residues was also amplified from the ϵ-globin promoter. PCR products were cloned in the pCR4 vector (TOPO TA cloning kits; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Mini-prepped DNA from individual random clones was sequenced using an ABI Prism 300 Genetic Analyzer by the DNA Sequencing Facility of the University of Illinois at Chicago Research Resources Center.

Phenotypic analysis by flow cytometry

After 9 days of culture, expanded marrow CD34+ cells were analyzed for cells expressing the phenotype of primitive HSCs flow cytometrically. Cells were stained with anti-human CD34+ mAb conjugated either to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE) and another mAb including anti-CD38, anti-CD117, anti-CD90. To determine the lineage-positive cells, a panel of mAbs all conjugated to FITC (anti-CD2, anti-CD14, anti-CD15, anti-CD19, and anti-GlyA; all antibodies were purchased from Becton Dickinson) were utilized. All analyses were paired with the corresponding matched isotype control of the specific mAb used. All staining and washes were performed in DPBS (Biowhittaker) and 0.5% BSA (Sigma). Immediately prior to FACS anaylsis 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI; Sigma) was added for the exclusion of nonviable cells for phenotypic anaylsis. Using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson), at least 10 000 live cells were acquired for each analysis.

Re-isolation of CD34+CD90- and CD34+CD90+ cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA and determination of their differentiation potential

After 9 days of ex vivo culture of marrow CD34+ cells in the presence of 5azaD and TSA and the cytokine combination described in “Ex vivo cultures,” cells were sorted using a FACSVantage into 2 populations based on CD90 expression (CD34+CD90+ and CD34+CD90- cells). Each subset of cells was placed in a secondary culture containing SCF, IL-3, IL-6, GM-CSF, TPO, and EPO to allow these cells to terminally differentiate. At the end of 7 days of secondary culture (9 + 7, total 16 days), cytospin preparations (Shandon, Runeorn, United Kingdom) of the cultured cells were stained with Wright-Giemsa for morphologic analysis. The cells obtained from these secondary cultures were also analyzed for phenotypic markers characteristic of the various blood lineages including CD11b, CD14, CD41, and CD71 using flow cytometry and assayed for their ability to form hematopoietic colonies in vitro.

Colony-forming cell assays

Colony-forming cells (CFCs) were assayed under standard conditions in semisolid media as previously described.24 Briefly, 1 × 103 primary CD34+ cells or unfractionated cultured cells exposed to different conditions used following 9 days of culture were plated in duplicate cultures containing one mL IMDM with 1.1% methylcellulose, 30% FBS, 5 × 10-5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Methocult; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), and a cocktail of growth factors including 100 ng/mL SCF, 5 U/mL EPO, 50 ng/mL IL-3, 50 ng/mL IL-6, and 50 ng/mL GM-CSF (Amgen). The cells were plated into 35-mm tissue-culture dishes (Costar), and after 14 days of incubation at 37° C in a 100%-humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, the colonies were scored with an inverted microscope following standard criteria.25

Cobblestone area–forming cell assays (CAFCs)

The ability of primitive HSC to form cobblestone areas (CAs) in long-term stromal cell–based marrow cultures has been used as an in vitro surrogate progenitor HSC assay.17,24-27 CD34+ cells after 9 days of culture from each condition were plated in limiting dilution in flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Costar) onto confluent, irradiated (7000 cGy) monolayers of the murine stromal fibroblast line M2-10B4 (a gift from Dr C. Eaves, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Each well contained 200 μL of a 50:50 mixture of IMDM and RPMI with 10% FBS and a cocktail of growth factors, including 100 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), 50 ng/mL IL-3, 50 ng/mL IL-6, and 50 ng/mL GM-CSF (Amgen). The cultures were fed weekly by replacement of one half of the culture volume with fresh medium containing the above cytokines at 2 times the previously defined concentration. After 5 weeks of culture in a humidified incubator at 37° C containing 5% CO2, the number of CAs were ennumerated. The CAFC frequency was computed by means of minimization of chi regression to the cell number at which 37% of wells were negative for CA formation, with 95% statistical precision using L-Calc (limiting dilution calculation) software (Stem Cell Technologies).27

Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) labeling to assess cell division

Freshly isolated CD34+ cells were labeled for 10 minutes at 37° C with 0.5 μmol CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in DPBS (Biowhittiker), a cytoplasmic dye that is equally diluted between daughter cells that are a product of a cell division, and washed 3 times with 10% FBS RMPI 1640. CFSE-labeled cells were then cultured as mentioned in “Ex vivo cultures” for 9 days and were analyzed for a progressive decline of fluorescence intensity, using a FACS Caliber cytometer (Becton Dickinson) on day 5 and day 9 following previously reported protocols.28

NOD/SCID assay for human marrow repopulating cells

Immunodeficient nonobese diabetic/ltsz-scid/scid (NOD/SCID) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were maintained as previously described.29 All NOD/SCID mice were kept under sterile conditions in the microisolator cages and were provided with autoclaved food and acidified water. Mice were given 300 cGy total body gamma irradiation and human grafts were injected via the tail vein. Various doses of primary marrow CD34+ cells following 9 days of culture with cytokines with or without 5azaD and TSA treatment were also injected. Cytokines including SCF, IL-3, and GM-CSF at 5 μg/mouse were injected intraperitoneally on alternate days following injection of human grafts during the first week of transplantation. Sulfamethoxazole (40 mg/mL) and trimethoprim (8 mg/mL; SMX/TMZ; Elkins-Sinn, Cherry Hill, NJ) were added to the drinking water for 3 days after injection and then subsequently for 3 days beginning the second week after the transplantation. Mice were killed after 7 to 8 weeks. Femurs and tibias were flushed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; Biowhittaker) with 2% FBS (Hyclone Laboratories) and 0.02% sodium azide, and cell counts were performed. Cells were preincubated with 1 mg/mL human gamma globulin in staining to block human Fc receptors. Murine Fc receptors were blocked by a second incubation of the cells in 2.4G2 (an anti–mouse Fc receptor mAb). Marrow cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to detect human cell engraftment as previously described.29 Briefly, to quantitate the total number of human cells present an aliquot of cells was stained with anti-CD45-FITC (Becton Dickinson) and anti-CD71-FITC (Becton Dickinson). This aliquot was also stained with anti-CD19-PE (Becton Dickinson) and cyanine-5-succinimidyl–labeled anti-CD34 (Becton Dickinson). The marrow cells were also plated in methylcellulose as previously described. Hematopoietic colonies were then pooled and stained with a mAb against human CD33 and human C-D45 (Becton Dickinson) to assess the presence of human cells.

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as the mean ± the standard error from the mean. Statistical significance was determined with the paired Student t test with significance at a P value of less than .05.

Results

Methylation status of marrow CD34+ with and without 5azaD and TSA treatment

To determine the methylation status of treated and untreated CD34+ marrow cells, COBRA was used to quantitate the DNA methylation of a CpG residue located at position -256 within the γ-globin promoter region. Primary CD34+ cells (day 0) initially were methylated at this promoter site (90%). These cells were then cultured for 5 days under various conditions outlined (Table 1). Methylation occurred in 87% of cells cultured for 5 days with cytokines alone, suggesting that the status of this promoter was unchanged throughout the culture period. By contrast, 58% of the cells treated with cytokines and sequential addition of 5azaD and TSA were methylated after culture (Table 1), indicating that these drugs are capable of altering cellular methylation patterns in vitro. Bisulfite sequence analysis of 5 CpG sites within the γ-globin gene promoter and 3 CpG sites within the ϵ-globin promoter was performed to confirm and extend the results of the COBRA assay. Six clones were sequenced from both the cells exposed to cytokines alone and from the cells exposed to cytokines and sequential 5azaD and TSA. Clones from the cells exposed to cytokines alone were completely methylated (100%) at all sites in all clones. In the cells exposed to sequential 5azaD and TSA, 21 (70%) of 30 CpG sites within the γ-globin promoter were methylated, and 12 (67%) of 18 sites were methylated within the ϵ-globin promoter (Table 1). It is important to point out that hypomethylation of the γ-globin gene promoter likely has little influence on stem cell behavior. These studies were, however, performed to show that 5azaD with or without TSA was capable of achieving hypomethylation of a known gene.

Effect of drug treatments on DNA methylation status

. | . | % methylation† . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell population . | % methylation* . | γ . | ϵ . | |

| Primary CD34+ cells‡ | 90 | NA | NA | |

| Cytokines alone§ | 87 | 100 | 100 | |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD | 32 | NA | NA | |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD/TSA | 58 | 70 | 67 | |

. | . | % methylation† . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell population . | % methylation* . | γ . | ϵ . | |

| Primary CD34+ cells‡ | 90 | NA | NA | |

| Cytokines alone§ | 87 | 100 | 100 | |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD | 32 | NA | NA | |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD/TSA | 58 | 70 | 67 | |

The table shows the effect of drug treatment on methylation status on position -256 of the γ-promotor region.

NA indicates not available.

Each value in this column represents the calculated methylation percent by densitometry by COBRA analysis of γ-globin gene

Bisulfite sequence analysis showing the percentage of methylated clones on 2 separate promoter sites of the ϵ- and γ-globin genes

Primary cells are the uncultured CD34+ cells selected from human marrow

CD34+ cells were cultured for 5 days in the cytokines IL-3, TPO, SCF, and FLT-3

Phenotype of CD34+ cells following 5azaD and TSA treatment

Next, we investigated the phenotype of marrow CD34+ cells prior to and after treatment with cytokines in vitro for a period of 9 days (Table 2). A 2-step culture system was set up. The cells were initially cultured in cytokines that promote HSC division to ensure their cycling and thus allow theoretically for the incorporation of 5azaD which was added after 16 hours of this culture. At 48 hours, TSA was added and the cytokines were changed to a combination which promotes terminal differentiation. This was done in order to detect a change in phenotype and function in the presence of an extreme external milieu favoring differentiation rather than HSC proliferation and self-renewal. During culture in cytokines alone, a progressive decline in the percentage and absolute number of CD34+ cells was observed as well as the percentage of CD34+ cells expressing a primitive HSC phenotype (CD90+, CD38-, c-kitlo, lin-; data not shown). In particular there was a significant decrease in the absolute number of CD34+CD90+ cells in these cultures (Table 3). By contrast, the CD34+ cells exposed to the same cytokines and sequential 5azaD and TSA retained the primitive HSC phenotype (Table 2) resulting in an expansion of CD34+CD90+ cell numbers (Table 3). Cells exposed to cytokines and to either 5azaD or TSA alone had a more limited expansion of CD34+CD90+ cell numbers (Table 3). To show that this effect could not be attributed merely to cytotoxicity, 5-FU was added to cultures instead of the 5azaD and TSA. 5-FU treatment has previously been utilized to select for primitive human progenitor cells in vitro.30 The CD34+CD90+ cell number in the 5-FU–treated cultures decreased significantly after 9 days (Table 3) so that by day 9 no CD34+CD90+ cells were observed. Marrow CD34+ cells following 9 days of culture exposed to 5azaD and TSA resulted in a 2.5-fold expansion of the CD34+CD90+ cell population.

Phenotype of CD34+ cells prior to and following drug treatment

Condition . | % CD90+ . | % CD117+ . | % CD38- . | % Lin-* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary CD34+ cells† | 26.0 ± 7.5† | 48.0 ± 6.4‡ | 8.7 ± 4.3‡ | 53.0 ± 16.2‡ |

| Cytokines plus sequential 5azaD and TSA | 77.0 ± 3.7 | 65.0 ± 20.0 | 18.3 ± 7.0 | 98.0 ± 0.7 |

Condition . | % CD90+ . | % CD117+ . | % CD38- . | % Lin-* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary CD34+ cells† | 26.0 ± 7.5† | 48.0 ± 6.4‡ | 8.7 ± 4.3‡ | 53.0 ± 16.2‡ |

| Cytokines plus sequential 5azaD and TSA | 77.0 ± 3.7 | 65.0 ± 20.0 | 18.3 ± 7.0 | 98.0 ± 0.7 |

The table shows the phenotype of CD34+ cells prior to and after exposure to 5azaD and TSA. Each value represents the mean of 3 experiments ± the standard error of the mean. There was no significant difference between the 2 cell populations as related to the expression of CD38, CD117, and lineage markers.

Lineage-negative represents those cells that do not express phenotypic markers associated with terminally differentiated cells (CD2, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD19, glycophorin A)

There is a significant increase in the percentage of CD90+ in the cytokines and sequential 5azaD- and TSA-treated culture when compared with the primary cells (P < .01, student paired t test)

Effects of drug treatment on numbers of CD34+ and CD34+CD90+ cells

Culture conditions . | Total mononuclear cell number, × 104 . | Absolute CD34+ number, × 104 . | Absolute CD34+CD90+ number, × 104 . | Fold expansion of CD34+CD90+ cells* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines alone | 640.0 ± 17 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.4† | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| Cytokines plus 5-FU | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD | 32.0 ± 5.0 | 10.0 ± 4.0 | 4.0 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 0.8 |

| Cytokines plus TSA | 470.0 ± 87.0 | 19.0 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD/TSA | 24.0 ± 4.0 | 12.0 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 2.0† | 2.5 ± 0.7† |

Culture conditions . | Total mononuclear cell number, × 104 . | Absolute CD34+ number, × 104 . | Absolute CD34+CD90+ number, × 104 . | Fold expansion of CD34+CD90+ cells* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines alone | 640.0 ± 17 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.4† | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| Cytokines plus 5-FU | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD | 32.0 ± 5.0 | 10.0 ± 4.0 | 4.0 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 0.8 |

| Cytokines plus TSA | 470.0 ± 87.0 | 19.0 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD/TSA | 24.0 ± 4.0 | 12.0 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 2.0† | 2.5 ± 0.7† |

The table shows the effect of drug treatment on numbers of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Each value represents the mean of 3 experiments ± the standard error of the mean.

Fold change is calculated as the change in CD34+CD90+ cell numbers of the treated cells as compared with the primary cell numbers

There was a significant increase in the number of CD34+CD90+ cells between the cells exposed to sequential 5azaD and TSA and the cells exposed to cytokines alone (P < .05, paired t test)

CFC potential of cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA

To ensure that a discordance between phenotype and function of the drug-treated progenitor cells did not exist, we evaluated the functional properties of these cells using CFC and CAFC assays, which are used to quantitate the number of differentiated and primitive HPCs, respectively. In addition, the ability of these various cell populations to engraft in vivo and differentiate into multiple hematopoietic lineages in immunodeficient NOD/SCID mice (SCID repopulating assays) was used as a surrogate assay for cells with marrow repopulating potential, a unique characteristic of primitive HSCs.

CD34+ cells treated with cytokines alone for 9 days contained dramatically reduced numbers of assayable progenitors in comparison to primary cells (Table 4). By contrast, unfractionated cells from cultures treated with cytokines and sequential 5azaD and TSA had dramatically greater numbers of HPCs than cultures receiving cytokines alone. Significantly, the drug-treated cultures contained greater numbers of multilineage progenitor cells than even the primary cells (Table 4). By contrast, cells assayed from the cultures treated with cytokines and 5-FU contained no assayable HPCs. The plating efficiency of CD34+ cells assayed immediately after selection (primary CD34+ cells) was 12.2% ± 0.5%, whereas that of the unfractionated cells, derived from the primary CD34+ cells, after 9 days of culture in cytokines alone was 0.8% ± 0.2%. The plating efficiency of the unfractionated cultured cells (50% CD34+ cells), derived from the primary CD34+ cells, exposed to cytokines in combination with 5azaD and TSA was 9.7% ± 0.2%, which was comparable to that of the primary CD34+ (92.5% pure)–selected cell population.

Ability of CD34+ cells exposed to 5azaD and or TSA to form hematopoietic colonies

Condition . | % CD34+ cells . | CFU-GM* . | BFU-E* . | CFU-MIX* . | Total number of colonies/plate* . | Plating efficiencies*† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary cells | 92.5 ± 2.5 | 52.0 ± 4.2 | 60.0 ± 1.8 | 10.0 ± 2.9 | 122.0 ± 4.9 | 12.2 ± 0.5 |

| Cytokines alone | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 7.8 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.25 ± 0.25 | 8.0 ± 2.0 | 0.8 ± 0.2‡ |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD | 31 ± 9.4 | 73.0 ± 0.25 | 4 ± 1.5 | 20.8 ± 9.3 | 97.8 ± 11.1 | 9.8 ± 1.1 |

| Cytokines plus TSA | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 13.0 ± 6.6 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 14.3 ± 8.1 | 1.4 ± 0.8 |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD/TSA | 50 ± 8.7 | 74.0 ± 4.1 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 21.0 ± 6.0 | 97.0 ± 2.0 | 9.7 ± 0.2‡ |

| Cytokines plus 5-FU | 26 ± 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Condition . | % CD34+ cells . | CFU-GM* . | BFU-E* . | CFU-MIX* . | Total number of colonies/plate* . | Plating efficiencies*† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary cells | 92.5 ± 2.5 | 52.0 ± 4.2 | 60.0 ± 1.8 | 10.0 ± 2.9 | 122.0 ± 4.9 | 12.2 ± 0.5 |

| Cytokines alone | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 7.8 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.25 ± 0.25 | 8.0 ± 2.0 | 0.8 ± 0.2‡ |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD | 31 ± 9.4 | 73.0 ± 0.25 | 4 ± 1.5 | 20.8 ± 9.3 | 97.8 ± 11.1 | 9.8 ± 1.1 |

| Cytokines plus TSA | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 13.0 ± 6.6 | 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 14.3 ± 8.1 | 1.4 ± 0.8 |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD/TSA | 50 ± 8.7 | 74.0 ± 4.1 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 21.0 ± 6.0 | 97.0 ± 2.0 | 9.7 ± 0.2‡ |

| Cytokines plus 5-FU | 26 ± 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

The table shows the ability of CD34+ cells exposed to 5azaD and or TSA to form hematopoietic colonies. All values are presented as mean ± the standard error of the mean.

Each number represents the mean of 2 experiments

Plating efficiency is defined as total number of (hematopoietic colonies/total cells plated) × 100

There is a significant increase in the total number of colonies when sequential addition of 5azaD and TSA is compared with cytokines alone (P<.01)

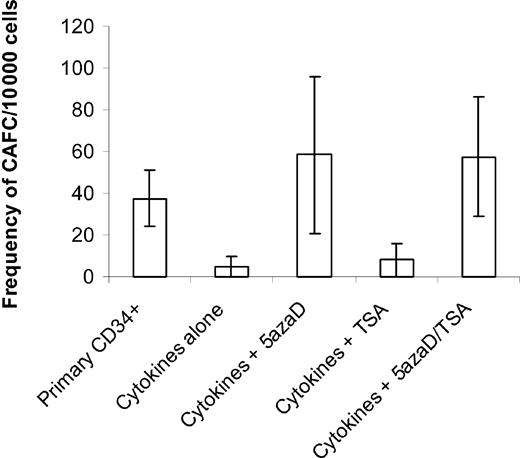

CAFCs assayed from 5azaD- and TSA-exposed cultures

To determine if the drug-treated (sequential 5azaD and TSA) CD34+ cells also contained more primitive HPCs, cultured cells were assayed for their ability to form CAs in long-term stromal cell–based marrow cultures (Figure 1). The CAFC assay is a well-established surrogate assay for primitive HPCs, which resemble HSCs. The primary CD34+ cells had a frequency of 37.5 ± 13.5 CAFCs per 10 000 CD34+ cells plated, while the unfractionated cells generated by exposure to cytokines alone demonstrated a 7.5-fold reduction in that frequency (5 ± 5 CAFCs per 10 000 cells). By contrast, the unfractionated cells generated by exposure of CD34+ cells to cytokines and sequential 5azaD and TSA enjoyed a 1.5-fold increase in the number of CAFCs (57.5 ± 28.6 CAFCs per 10 000 cells) over that of the purified primary CD34+ cells. Cells exposed to 5azaD alone achieved a 1.6-fold (58.5 ± 37.6 CAFCs per 10 000 cells) increase in the CAFC numbers, indicating that demethylation might play a critical role in reactivating genes at the level of the CAFCs. By contrast, cultures treated with TSA alone contained comparable numbers of CAFCs as cultures receiving cytokines alone (Figure 1).

Frequency of CAFCs after 9 days of culture in different conditions. Either primary CD34+ cells or cells cultured in a cytokine combination in the presence or absence of 5azaD and TSA for 9 days were analyzed for their ability to form CAFCs. The number of CAs was expressed out of 10 000 cells plated. CAFC frequency was computed using minimization by regression to the cell number at which 37% of wells showed negative CAFC growth with 95% statistical precision. The bar graph represents mean ± SE of 2 experiments done in limiting dilution where each concentration of cells is tested 24 times.

Frequency of CAFCs after 9 days of culture in different conditions. Either primary CD34+ cells or cells cultured in a cytokine combination in the presence or absence of 5azaD and TSA for 9 days were analyzed for their ability to form CAFCs. The number of CAs was expressed out of 10 000 cells plated. CAFC frequency was computed using minimization by regression to the cell number at which 37% of wells showed negative CAFC growth with 95% statistical precision. The bar graph represents mean ± SE of 2 experiments done in limiting dilution where each concentration of cells is tested 24 times.

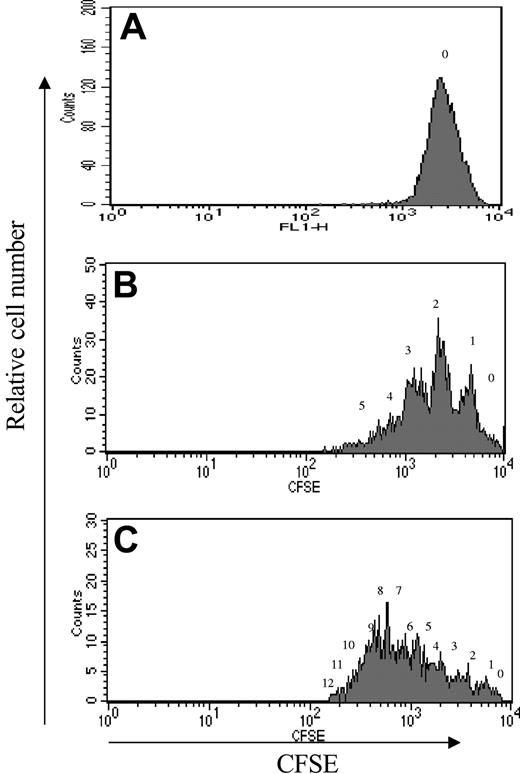

Cell division of CD34+CD90+ cells in culture

In order to determine whether the increase in CD34+CD90+ cells in the culture exposed to 5azaD and TSA was due to a retention of the quiescent population of HSCs, we examined the cell division history of CD34+CD90+ cells generated in vitro using CFSE staining. CD34+CD90+ cells present in the culture were analyzed for progressive loss of fluorescence intensity of CFSE after 5 and 9 days of incubation (Figure 2). The CD34+CD90+ cell population underwent multiple cell divisions after 5 and 9 days of incubation. In fact after 9 days of culture there were no CD34+CD90+ cells that had not divided. These studies demonstrate that the phenotype and functional effects attributed to 5azaD and TSA are not due to preservation of quiescent cells but rather occur subsequent to multiple cell divisions by the cultured CD34+CD90+ cells. In order to determine whether the effect of these pharmacologic agents was directed against the CD34+CD90+ or CD34+CD90- cells, these cell populations were isolated and pretreated individually with 5azaD and TSA and incubated for 9 days as previously described (Table 5). After 9 days the numbers of CD34+CD90+ cells were increased 1.3-fold in the cultures initiated with isolated CD34+CD90+ cells. Since these CD34+CD90+ cells were undergoing active division (Figure 2), this effect was a consequence of HSC self-replication rather than quiescence. Surprisingly, a significant population of CD34+CD90-cells became CD34+CD90+ after drug treatment. Since the increase in the CD34+CD90+ cell number was similar when one combined the resultant cellular products of the cultures initiated with subpopulations of CD34+ cells treated to that observed in cultures of unfractionated CD34+ cell population, the increase in CD34+CD90+ cells could be accounted for by 2 simultaneously acting mechanisms: (1) selfreplication of CD34+CD90+ cells, and (2) conversion of CD34+CD90- cells to CD34+CD90+ cells.

CFSE-labeled cell division history of CD34+ CD90+ after 9 days of culture. Cell division history of CD34+CD90+ exposed to 5azaD and TSA with cytokine cocktail (described in “Materials and methods”) after 5 and 9 days of culture labeled with CFSE. Each panel shows a representative flow cytometry profile for CFSE fluorescence intensity as a function of cell number for each day studied. (A) Uncultured marrow CD34+ cells. (B) CD34+CD90+ cells after 5 days of culture treated with 5azaD and TSA. (C) CD34+CD90+ cells after 9 days of culture treated with 5azaD and TSA. The number above each peak indicates the number of cell divisions undergone by cells within each peak of CFSE fluorescence.

CFSE-labeled cell division history of CD34+ CD90+ after 9 days of culture. Cell division history of CD34+CD90+ exposed to 5azaD and TSA with cytokine cocktail (described in “Materials and methods”) after 5 and 9 days of culture labeled with CFSE. Each panel shows a representative flow cytometry profile for CFSE fluorescence intensity as a function of cell number for each day studied. (A) Uncultured marrow CD34+ cells. (B) CD34+CD90+ cells after 5 days of culture treated with 5azaD and TSA. (C) CD34+CD90+ cells after 9 days of culture treated with 5azaD and TSA. The number above each peak indicates the number of cell divisions undergone by cells within each peak of CFSE fluorescence.

Phenotypic analysis of CD34+CD90+ and CD34+CD90- cells treated with 5azaD and TSA

. | . | Following ex vivo culture for 9 days . | . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting cell subset . | Total starting CD34+CD90+ cell counts, × 104* . | Total cell counts, × 104 . | % CD34+CD90+ . | Number of CD34+CD90+, × 104 . | Fold expansion of CD34+CD90+ . | |||

| CD34+CD90+ | 1.5 (1.5) | 2.25 | 82.2 | 1.85 | 1.3 | |||

| CD34+CD90- | 3.5 (0) | 3.0 | 51.4 | 1.5 | NA | |||

| CD34+ | 11.0 (3.5) | 56.0 | 9.7 | 5.5 | 1.6 | |||

. | . | Following ex vivo culture for 9 days . | . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting cell subset . | Total starting CD34+CD90+ cell counts, × 104* . | Total cell counts, × 104 . | % CD34+CD90+ . | Number of CD34+CD90+, × 104 . | Fold expansion of CD34+CD90+ . | |||

| CD34+CD90+ | 1.5 (1.5) | 2.25 | 82.2 | 1.85 | 1.3 | |||

| CD34+CD90- | 3.5 (0) | 3.0 | 51.4 | 1.5 | NA | |||

| CD34+ | 11.0 (3.5) | 56.0 | 9.7 | 5.5 | 1.6 | |||

The table shows the effect of 5azaD and TSA on purified CD34+ marrow cells sorted using FACSVantage based on CD90 expression. This represents cells of a representative study. Similar results were obtained in an additional experiment. NA indicates not applicable.

Each number represents the total number of cells started at the beginning of the culture period. The number in parentheses represents the number of CD34+CD90+ cells at the start of the culture

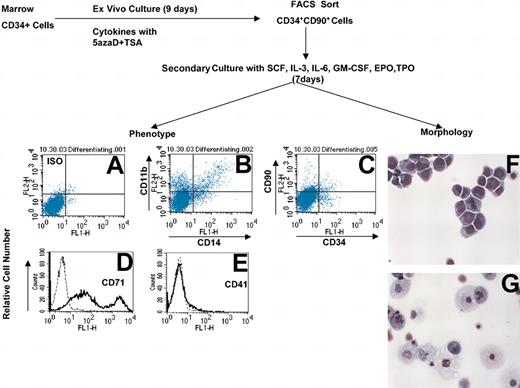

Differentiation potential of CD34+CD90+ cells re-isolated from cultures exposed to 5azaD and TSA

To further evaluate the differentiative potential of cells generated following 9 days of culture in the presence of cytokines and treatment with 5azaD and TSA, cells were sorted into 2 subsets using a FACSVantage (CD34+CD90+ and CD34+CD90- cells). These cells were placed in a secondary culture containing IL-3, SCF, TPO, GM-CSF, EPO, and IL-6 for an additional 7 days to assess their ability to terminally differentiate. The re-isolated CD34+CD90+ cells were capable of differentiation into cells belonging to all blood lineages (Figure 3B-E). Morphologic examination of the cells derived from the CD34+CD90+ cells that were exposed to 5azaD and TSA (Figure 3F) revealed that 68% of the cells were blastlike forms while the culture that had been exposed to the same cytokines but no 5azaD and TSA was composed of primarily terminally differentiated cells, macrophages (54%) and normoblasts (44%) (Figure 3G). In addition, CD34+CD90+ as well as CD34+CD90- cells obtained after 9 days in culture were assayed for HPCs. When plated in methylcellulose these cells formed colonies composed of cells belonging to all blood lineages (Table 6). Only the CD34+CD90+ subset however, contained CFU-mix colonies and had a far higher plating efficiency in comparison to the CD34+CD90- cells (13.2% versus 7.2%). Furthermore, the cells generated from the CD34+CD90+ cells that had been re-isolated from cultures treated with 5azaD and TSA and then cultured in differentiating cytokines alone for an additional 7 days still retained the ability to form colonies in vitro after a total of 16 days of culture (plating efficiency 2.4%) (data not shown).

CD34+CD90+ cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA are capable of differentiating into multiple blood cell lineages. Displayed is the schema used to evaluate the differentiation potential of CD34+CD90+ cells after exposure to 5azaD and TSA. After 9 days of initial culture (described in “Materials and methods”) cells were sorted into 2 subsets, CD34+CD90+ and CD34+CD90-, and then placed in a secondary culture supplemented with IL-3, IL-6, GM-CSF, TPO, SCF, and EPO. The phenotype of cells was determined by staining with monoclonal antibodies directed toward CD41, CD71, CD11b, CD14, CD34, and CD90. Each panel shows a representative flow cytometric profile with each of these monoclonal antibodies: (A) isotype matched control; (B) CD11b and CD14; and (C) CD34+ and CD90+. (D) mAb stain with CD71 (dotted line is the matched isotype control; the continuous line represents CD71 mAb staining). (E) Single antibody stain with CD41 (dotted line is the matched isotype control; the continuous line represents CD41 mAb staining). (F-G) Cytospin preparations were stained with Giemsa and Wright stain and were viewed with a light microscope (original magnification × 400). Each panel is represented as follows: (F) CD34+CD90+ cells after 16 days of culture with pretreatment with 5azaD and TSA; and (G) marrow CD34+ cells cultured for total of 16 days, not exposed to 5azaD and TSA.

CD34+CD90+ cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA are capable of differentiating into multiple blood cell lineages. Displayed is the schema used to evaluate the differentiation potential of CD34+CD90+ cells after exposure to 5azaD and TSA. After 9 days of initial culture (described in “Materials and methods”) cells were sorted into 2 subsets, CD34+CD90+ and CD34+CD90-, and then placed in a secondary culture supplemented with IL-3, IL-6, GM-CSF, TPO, SCF, and EPO. The phenotype of cells was determined by staining with monoclonal antibodies directed toward CD41, CD71, CD11b, CD14, CD34, and CD90. Each panel shows a representative flow cytometric profile with each of these monoclonal antibodies: (A) isotype matched control; (B) CD11b and CD14; and (C) CD34+ and CD90+. (D) mAb stain with CD71 (dotted line is the matched isotype control; the continuous line represents CD71 mAb staining). (E) Single antibody stain with CD41 (dotted line is the matched isotype control; the continuous line represents CD41 mAb staining). (F-G) Cytospin preparations were stained with Giemsa and Wright stain and were viewed with a light microscope (original magnification × 400). Each panel is represented as follows: (F) CD34+CD90+ cells after 16 days of culture with pretreatment with 5azaD and TSA; and (G) marrow CD34+ cells cultured for total of 16 days, not exposed to 5azaD and TSA.

CFC potential of re-isolated CD34+CD90+ cells from cultured cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA

Cell subset . | CFU-GM . | BFU-E . | CFU-MIX . | Total . | Plating efficiency . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34+CD90+ | 56 | 7 | 3 | 66 | 13.2 |

| CD34+CD90- | 15 | 21 | 0 | 36 | 7.2 |

Cell subset . | CFU-GM . | BFU-E . | CFU-MIX . | Total . | Plating efficiency . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34+CD90+ | 56 | 7 | 3 | 66 | 13.2 |

| CD34+CD90- | 15 | 21 | 0 | 36 | 7.2 |

After 9 days of culture, cells were sorted into 2 subsets according to expression of CD90. Cells (500) were plated in 1 mL methylcellulose in duplicates and scored after 14 days. Each value represents the mean number of colonies scored from duplicate cultures.

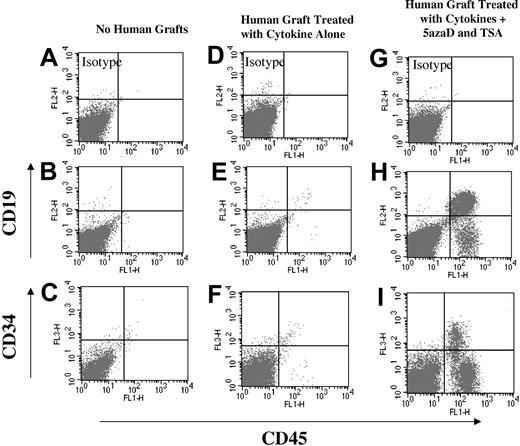

Repopulating potential of cultured cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA

The ability of human HSCs to engraft and differentiate into multiple hematopoietic lineages in vivo is an established surrogate functional HSC assay.29 Primary CD34+ cells (pretreatment control) engrafted within NOD/SCID mice and were capable of generating multiple human hematopoietic lineages in vivo (data not shown) while cells exposed to cytokines alone (Figure 4) or cytokines and TSA (data not shown) no longer possessed such marrow repopulating capability. However, both cells exposed to cytokines and 5azaD alone (data not shown) or cytokines and sequential 5azaD and TSA following 9 days of culture retained the ability to engraft NOD/SCID mice and to generate cells belonging to multiple human hematopoietic lineages to a degree similar to that in primary cells (Figure 4).

FACS analysis of marrow cells isolated from NOD/SCID mice 7 weeks after injection of human cell grafts. Cells were stained for human CD45, CD19, CD41, and CD34 to assess multilineage engraftment. (A-C) Analysis of a mouse (n = 1) that did not receive any human cell graft (negative control). (D-F) Analysis of the marrow from mice (n = 4) receiving cells exposed to cytokines alone. (G-I) Analysis of the marrow from mice (n = 3) receiving cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA. (A) Isotype negative control. (B) CD19 PE and CD45 FITC negative control. (C) CD34 PE and CD45 FITC negative control. (D) Isotype cytokines alone. (E) CD19 PE and CD45 FITC cytokines alone. (F) CD34 PE and CD45 FITC exposed to cytokines alone. (G) Isotype exposed to 5azaD and TSA. (H) CD19 PE and CD45 FITC of cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA. (I) CD34 PE and CD45 FITC exposed to 5azaD and TSA.

FACS analysis of marrow cells isolated from NOD/SCID mice 7 weeks after injection of human cell grafts. Cells were stained for human CD45, CD19, CD41, and CD34 to assess multilineage engraftment. (A-C) Analysis of a mouse (n = 1) that did not receive any human cell graft (negative control). (D-F) Analysis of the marrow from mice (n = 4) receiving cells exposed to cytokines alone. (G-I) Analysis of the marrow from mice (n = 3) receiving cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA. (A) Isotype negative control. (B) CD19 PE and CD45 FITC negative control. (C) CD34 PE and CD45 FITC negative control. (D) Isotype cytokines alone. (E) CD19 PE and CD45 FITC cytokines alone. (F) CD34 PE and CD45 FITC exposed to cytokines alone. (G) Isotype exposed to 5azaD and TSA. (H) CD19 PE and CD45 FITC of cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA. (I) CD34 PE and CD45 FITC exposed to 5azaD and TSA.

After sacrificing the mice, marrow cells from each of these groups were plated in semisolid media in the presence of human cytokines and the number of secondary hematopoietic colonies enumerated. These studies were performed in order to determine if the transplanted human grafts continued to possess the ability to generate secondary progenitor cells. Only marrow cells from mice receiving primary CD34+ cells or cultures treated with 5azaD alone or sequential 5azaD and TSA produced significant numbers of secondary hematopoietic colonies (Table 7) in vitro. The colonies were then pooled and stained with a mAb directed against human CD45 and CD33 in order to determine if colonies were composed of human or murine cells (Table 7). The colonies cloned from the marrow of mice receiving sequential 5azaD- and TSA-treated human grafts contained greater numbers of human hematopoietic cells than the mice receiving grafts treated with 5azaD alone. This suggests that sequential addition of 5azaD and TSA may play a role in preserving and reactivating gene expression patterns required for the maintenance of marrow repopulating potential despite several cell divisions occurring during ex vivo culture.

Hematopoietic colonies cloned from NOD/SCID mouse marrow

Human grafts . | % human cells . | Estimated number of human colonies* . |

|---|---|---|

| Primary CD34+ cells | 88 | 47 |

| Cytokines alone | 0 | 0 |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD | 12 | 9 |

| Cytokines plus TSA | 0 | 0 |

| Cytokines plus sequential 5azaD and TSA | 91 | 26 |

Human grafts . | % human cells . | Estimated number of human colonies* . |

|---|---|---|

| Primary CD34+ cells | 88 | 47 |

| Cytokines alone | 0 | 0 |

| Cytokines plus 5azaD | 12 | 9 |

| Cytokines plus TSA | 0 | 0 |

| Cytokines plus sequential 5azaD and TSA | 91 | 26 |

The table shows the number of colonies after plating marrow cells from mice that received human grafts 7 weeks earlier.

The estimated number of human colonies is determined by the percentage of human cells composing the pooled hematopoietic colonies from a group of mice that stained positively with mAbs against CD45/CD33 antibodies using FACS analysis multiplied by the total number of colonies enumerated

We further investigated the repopulating activity of these ex vivo–cultured cells by assessing the marrow repopulating potential of various doses of primary and cultured cells in NOD/SCID mice. Individual mice were scored as positive only when the number of human (CD45+) cells present 8 weeks after transplantation constituted more than or equal to 0.1% of the total nucleated mouse marrow cells (Table 8). The CD34+ cells exposed to cytokines alone for 9 days did not show any hematopoietic engraftment capacity at any cell dose given. By contrast, the CD34+ cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA for 9 days maintained multilineage hematopoietic engraftment capabilities (CD19+, CD45+, CD33+, and CD34+ cells). It is important to point out that 95% of the primary marrow cells were CD34+ while only 60% of the cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA after 9 days of culture were CD34+ by flow cytometric analysis. Thus the actual number of CD34+ cells in grafts of cultured cells was less than that of grafts containing primary CD34+ cells.

Engraftment of various numbers of human marrow CD34+ cells treated with 5azaD and TSA in NOD/SCID mice

Cell dose injected . | Primary CD34+ (95)* . | Cytokines alone (2.9)† . | Cytokines plus 5azaD/TSA (56.4)‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × 106 | 2/2 | 0/3 | 1/2 |

| 1 × 105 | 3/3 | NA | 1/3 |

| 1 × 104 | 1/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| 1 × 103 | 0/3 | NA | 0/3 |

| 1 × 102 | 0/3 | NA | 0/3 |

Cell dose injected . | Primary CD34+ (95)* . | Cytokines alone (2.9)† . | Cytokines plus 5azaD/TSA (56.4)‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × 106 | 2/2 | 0/3 | 1/2 |

| 1 × 105 | 3/3 | NA | 1/3 |

| 1 × 104 | 1/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| 1 × 103 | 0/3 | NA | 0/3 |

| 1 × 102 | 0/3 | NA | 0/3 |

This table shows the marrow repopulating potential of various doses plus cells injected from 3 different conditions. Numbers in parentheses indicate the percentage of CD34+ cells in the population injected at each dose. Data represent number of mice engrafted/total number of mice injected. Individual mice were scored as positive only when the number of human (CD45+) cells present 6 to 8 weeks after transplantation constituted ≥ 0.1% of the total marrow population by flow cytometry. NA indicates not available.

Primary CD34+ cells represent a pretreatment control, not cultured

Untreated CD34+ marrow cells, cytokines alone, were cultured for 9 days

5azaD- and TSA-treated cells were cultured for 9 days

Discussion

Epigenetic events play important roles in many biologic functions, including transcriptional regulation and cell programming which occur during gametogenesis.1 This critical biologic process has been linked to events including aging, neoplasia, and a growing number of developmental disorders in man.3,31 HSCs possess the capacity to self-renew and differentiate into multiple hematopoietic lineages throughout the lifespan of an individual. This is a complex process that involves a hierarchy of HSCs, which can be influenced by a variety of external regulatory factors. Whether the fate of an individual HSC is determined by random or stochastic events or can actually be defined by external influences remains an important area of investigation.32,33 To date, attempts to create an in vitro environment that favors HSC self-replication rather than commitment and differentiation has resulted in limited success.7,16,19,30,34

Although the molecular signature that defines an HSC has recently been described, the patterns of gene expression that lead to HSC self-replication rather than commitment remain unkown.11,12 Primitive HSCs are thought to maintain an open chromatin structure that permits access to the entire HSC developmental program while more differentiated cells along the hematopoietic hierarchy are thought to characteristically undergo a stepwise progression of epigenetic events that controls transcriptional events for each stage and class of progenitor cells.9 HSCs promiscuously express a set of transcription factors that are restricted as the process of commitment to a particular pathway of differentiation occurs.7,9,35 These events likely involve the activation and or silencing of yet-to-be-identified groups of pivotal genes.

We have used 2 classes of drugs, DNA hypomethylating agents (5azaD) and HDACI (TSA) to explore the influences of these agents on decisions determining HSC fate. Hypomethylation is a molecular mechanism by which previously silenced genes can be reactivated while HDACIs maintain acetylation of histones thereby altering chromatin structure to promote gene expression.5,36 Our studies show that sequential addition of 5azaD and TSA in the presence of cytokines, which favor differentiation, results rather in the retention of stem cell phenotype, number, and function. It has been demonstrated that there is a discordance between phenotype and function in culture-expanded cells.37 Recently, the CD34+CD90+ cell subset after in vitro culture has been shown to be the most reliable predictor for SCID repopulating potential.38 Although the effects of 5azaD in part could be explained by its ability to induce HSC cytotoxicity and thereby select for a primitive subset of HSC, this explanation is unlikely to account solely for our observations. A similar preservation of HSC phenotype, number, and function was not achieved with treatment with 5-FU, a cytotoxic agent frequently utilized to select for primitive progenitor cells and HSCs in vivo and in vitro.30 Following the exposure of CD34+ cells to 5-FU, the numbers of CD34+ cells radically decreased and never recovered in the presence of the cytokine combination utilized.

It is important to point out that the addition of TSA alone to the cultured cells resulted in preservation of CD34+ cell number but not function, while the addition of 5azaD alone preserved cell number and function of primitive HSCs. The combination of 5azaD and TSA yielded the highest number of CD34+CD90+ cells after 9 days of culture despite being in the presence of a cytokine cocktail that favored terminal differentiation. In addition, there were more secondary human colonies cloned from NOD/SCID mouse marrow that received 5azaD- and TSA-treated grafts than 5azaD-treated grafts, suggesting that TSA in conjunction with 5azaD further increased the number of cells responsible for SCID repopulating activity and thus plays a role at this level in HSC hierarchy. It has been shown that initial addition of 5azaD may unlock genes that are not readily accessible by HDACIs, and that the addition of an HDACI causes robust gene re-expression.39 DNA methylation appears to be a dominant process and that demethylation caused by low doses of drugs are capable of synergistically interacting with histone deacetylases resulting in the re-expression of silenced genes.40 This may explain why TSA addition alone was unable to preserve the function of primitive HSCs.

Whether the CD34+ cells exposed to 5azaD and TSA acquire a unique gene expression pattern crucial for maintenance of primitive HSCs remains to be determined. It appears likely however, that the transcriptional program normally associated with in vitro terminal differentiation of CD34+ cells has been interrupted briefly, possibly by the reactivation of genes associated with the preservation of phenotypically identifiable HSC populations. It has been reported previously that following a limited number of cell divisions HSCs lose their phenotypic characteristics, clonogenic potential, and SCID repopulating potential.41 However, in our current study, CD34+ cells, despite being in conditions favoring terminal differentiation and having undergone more than 12 divisions following 9 days of the culture period, still contained both primitive and differentiated HPCs and retained SCID repopulating potential. In contrast, CD34+ cells cultured under the same conditions without 5azaD and TSA did not contain any detectable clonogenic cells in vitro or SCID repopulating cells. This redirection of the fate of primitive HSCs may be associated with the alteration of the methylation status of DNA. Methylation is capable of changing the interactions between proteins and DNA, which leads to alterations in chromatin structure and either a decrease or increase in the rate of transcription.42 Specific DNA methylation patterns have been reported to be responsible for gene expression patterns associated with specific tissues.3,4,36 We have shown that hypomethylation was achieved in the γ-globin gene promoter that we used as a marker for changes in methylation status. It is likely that other pivotal genes have been affected by the drug treatments that require identification in the future.

Actual HSC fate decisions may be governed by the expression patterns of transcription factors that may be under the control of methylation and deacetylation of chromatin, while commitment or differentiation might be triggered and regulated by external regulatory pathways, activated by interactions of HSCs with cytokines or the marrow microenvironment. Once these gene expression patterns are known, small molecules might be identified that would favor their activation leading to the in vitro maintenance or expansion of not only HSCs but possibly stem cells belonging to a variety of other somatic tissues. Since the alteration of HSC fate described here occurred in the presence of a cytokine combination that favors differentiation, it appears likely that the sequential drug treatments implemented resulted either in dedifferentaion of cells driven toward their terminal fate or interruption of the ongoing differentiation process.43

This model of HSC behavior offers a new paradigm by which to elucidate the behavior of a stem cell. Such strategies may lead to novel approaches resulting in in vitro stem cell expansion or promotion of gene expression of a transgene following stem cell modification using a variety of gene delivery systems. Knowledge of epigenetic events that govern HSC fate may also result in a more complete understanding of the basic properties of normal as well as malignant HSCs.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 19, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2431.

Supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the state of Illinois.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

Hetal Patel and Wenxin Pang are acknowledged for their technical assistance. Raphael Nunez is acknowledged for his assistance with cell sorting.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal