Abstract

The first immune cell to arrive at the site of infection is the neutrophil. Upon arrival, neutrophils quickly initiate microbicidal functions, including the production of antimicrobial products and proinflammatory cytokines that serve to contain infection. This allows the acquired immune system enough time to generate sterilizing immunity and memory. Neutrophils detect the presence of a pathogen through germ line-encoded receptors that recognize microbe-associated molecular patterns. In vertebrates, the best characterized of these receptors are Toll-like receptors (TLRs). We have determined the expression and function of TLRs in freshly isolated human neutrophils. Neutrophils expressed TLR1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10—all the TLRs except TLR3. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) treatment increased TLR2 and TLR9 expression levels. The agonists of all TLRs expressed in neutrophils triggered or primed cytokine release, superoxide generation, and L-selectin shedding, while inhibiting chemotaxis to interleukin-8 (IL-8) and increasing phagocytosis of opsonized latex beads. The response to the TLR9 agonist nonmethylated CpG-motif-containing DNA (CpG DNA) required GM-CSF pretreatment, which also enhanced the response to the other TLR agonists. Finally, using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR), we demonstrate a chemokine expression profile that suggests that TLR-stimulated neutrophils recruit innate, but not acquired, immune cells to sites of infection. (Blood. 2003;102:2660-2669)

Introduction

Neutrophils are the most abundant immune cell found in human blood. These cells quickly arrive at sites of infection and form the first line of defense following infection. Neutrophils possess a large variety of antimicrobial effector functions as well as the ability to produce cytokines to initiate inflammatory responses and chemokines to induce trafficking of immune cells.1

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are type 1 transmembrane receptors that play an important role in innate immune recognition of pathogens.2 Recognition of conserved molecular patterns found on microbes by these invariant, germ line-encoded receptors leads to a signal transduction cascade that results in cellular activation and cytokine release in both immune and nonimmune cells.

Because neutrophils are the prototypical innate immune cell and TLRs are the prototypical innate immune receptor, we and others have started to investigate the role of individual TLRs in neutrophil function.3-5 In this report, we have investigated the role of a panel of TLRs in a number of innate immune functions of freshly isolated human neutrophils. Human neutrophils express most of the TLRs so far described: TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. Signaling through these receptors (triggered by purified stimuli for these receptors) results in the production of interleukin-8 (IL-8), triggers the shedding of L-selectin on their surface, primes for N-formylatedmethionine-leucine-phenylalanine peptide (fMLF)-mediated superoxide production, increases the rate of phagocytosis, and decreases IL-8-induced chemotaxis. We have also examined the transcription of a number of cytokines and chemokines using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) in neutrophils stimulated with purified TLR agonists.

Previous reports demonstrate an increase in neutrophil function upon granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) treatment, and a recent report showed synergy between GM-CSF and TLR2.4 We were able to confirm and extend these findings to other TLRs. We observed enhanced expression of TLR2 and TLR9 following GM-CSF treatment. Neutrophil activation in response to the TLR9 agonist nonmethylated CpG-motif-containing DNA (CpG DNA) was undetectable without GM-CSF pretreatment. We also demonstrate enhanced responses to the other TLR agonists in GM-CSF-pretreated neutrophils, suggesting that increased receptor expression is not the only mechanism resulting in TLR/GM-CSF receptor synergy.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Human and murine IL-4 and GM-CSF were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Zymosan A (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli K12) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). LPS was further purified from contaminant lipoproteins normally found in commercially available LPS preparations by double phenol extraction.6 Synthetic lipopeptide Pam3-Cys-Ser-Lys4 was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA). Flagellin (fliC) was purified from Salmonella typhimurium as previously described.7 The flagellin preparation used in these studies contained less than 0.2 pg/mL LPS per microgram of protein as assayed by Limulus amoebocyte assay. This purified flagellin activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with TLR5 but not with TLR2 or TLR4 (data not shown). Polyinosine-polycytidylic acid (poly I:C) (dsRNA) was purchased from Pharmacia (Uppsala, Sweden). R848 (resiquimod hydrochloride) was purchased from GL Synthesis (Worcester, MA) and resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Oligodeoxynucleotide CpG-A (GGTGCATCGATGCAGGGGGG) was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless stated otherwise.

Human neutrophil isolation

The experiments conducted in this report were performed with human neutrophils isolated from 5 different individuals. Aside from the numbers of neutrophils recovered, there were no noticeable differences in the cells isolated from different individuals. A total of 10 to 20 mL human blood was isolated from healthy donors using 1 to 2 mL heparin to prevent clotting. All subsequent steps were performed at 4°C or on ice. The blood was diluted 1:1 with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) with 2% Dextran T500 (Pharmacia) and incubated 30 minutes to sediment red blood cells. The upper phase was transferred to a new tube and density fractionated using Histopaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich). The pellet was transferred to a new tube and resuspended in RBC lysis buffer and then washed with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% low-endotoxin fetal bovine serum (FBS). Typical recovery was 3 to 5 million neutrophils per milliliter of collected blood. Purity was more than 95% as measured by differential count following Diff-Quick staining. Neutrophils were isolated before each experiment and used immediately. Cell morphology was inspected microscopically to rule out cell preparations that had become activated during isolation.

TLR stimulation

Neutrophils were isolated as above and diluted to 1 × 106 cells per milliliter. LPS, lipopeptide, flagellin, and zymosan were sonicated for 5 minutes prior to use. TLR agonists were used at the following concentrations unless otherwise noted: LPS, 100 ng/mL; lipopeptide, 100 ng/mL; poly I:C, 50 μg/mL; flagellin, 300 ng/mL; CpG DNA, 50 μg/mL; zymosan, 50 μg/mL; R848, 10 μM. Neutrophils were stimulated in 48-well tissue-culture plates, and cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1 hour unless otherwise noted. GM-CSF pretreatment was performed similarly using 50 ng/mL recombinant human GM-CSF (Peprotech) and incubated for 1.5 hours unless otherwise noted. Supernatants were used in subsequent enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) to measure cytokine levels, and the cells were labeled for surface molecules or lysed in RLT buffer (Qiagen) for RNA extraction.

QPCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen). Briefly, after DNase I (Invitrogen) treatment, 1 μg total RNA from each sample was used as template for the reverse transcription reaction; 100 μL cDNA was synthesized using Oligo(dT)15, random hexamers, and Multiscribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany). All samples were reverse transcribed under the same conditions (25°C for 10 minutes, 48°C for 30 minutes) and from the same reverse transcription master mix to minimize differences in reverse transcription efficiency. All oligonucleotide primers for QPCR were synthesized by Invitrogen. The primers used are listed in Table 1. Oligonucleotide primers were designed using Primer Express software 1.0 (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The QPCR reaction was performed in 25 μL with 2 μL cDNA, 12.5 μL 2 × SYBR Green master mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and 250 nmol sense and antisense primer. The QPCR reactions were performed in optical 96-well strips with optical caps using the MX4000 Multiplex quantitative PCR system (Stratagene). The same thermal profile conditions were used for all primer sets. The reaction conditions were as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. Emitted fluorescence for each reaction was measured 3 times during the annealing/extension phase, and amplification plots were analyzed using MX4000 software version 3.0 (Stratagene). A series of standards was prepared by performing 10-fold serial dilutions of full-length cDNAs in the range of 20 million copies to 2 copies per QPCR reaction. Quantity values (ie, copies) for gene expression were generated by comparison of the fluorescence generated by each sample with standard curves of known quantities. Next, the calculated number of copies was divided by the number of copies of β2-microglobulin. β2-microglobulin was selected as a normalizing gene empirically, because it has stable expression levels in the conditions tested. In addition, we saw no significant changes in the QPCR results when the data were normalized using another constitutively transcribed gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Primers used for QPCR

Human mRNA . | Forward primer . | Reverse primer . | Accession no. . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL1/GRO-α | ACGTGAAGTCCCCCGGAC | GCCCATTCTTGAGTGTGGCT | NM_001511 |

| CXCL8/IL-8 | CTGGCCGTGGCTCTCTTG | CCTTGGCAAAACTGCACCTT | NM_000584 |

| CXCL9/MIG | TGCAAGGAACCCCAGTAGTGA | GGTGGATAGTCCCTTGGTTGG | NM_002416 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | TGAAATTATTCCTGCAAGCCAA | CAGACATCTCTTCTCACCCTTCTTT | NM_001565 |

| CXCL11/I-TAC | CAAGGCTTCCCCATGTTCA | CCACTTTCACTGCTTTTACCCC | NM_005409 |

| CXCL13/BCA | GACGCTTCATTGATCGAATTCA | TTCCAGACTATGATTTCTTTTCTTGG | NM_006419 |

| CCL2/MCP-1 | CTCTGCCGCCCTTCTGTG | TGCATCTGGCTGAGCGAG | NM_002982 |

| CCL3/MIP-1α | AGCTGACTACTTTGAGACGAGCA | CGGCTTCGCTTGGTTAGGA | NM_002983 |

| CCL4/MIP-1β | CTGCTCTCCAGCGCTCTCA | GTAAGAAAAGCAGCAGGCGG | NM_002984 |

| CCL5/RANTES | GACACCACACCCTGCTGCT | TACTCCTTGATGTGGGCACG | NM_002985 |

| CCL19/MIP-3β | GGCACCAATGATGCTGAAGA | GAAGTTCCTCACGATGTACCCAG | NM_006274 |

| CCL20/MIP-3α | TCCTGGCTGCTTTGATGTCA | TCAAAGTTGCTTGCTGCTTCTG | NM_004591 |

| IL-1β | ACGAATCTCCGACCACCACT | CCATGGCCACAACAACTGAC | M15330 |

| IL-4 | GGCAGTTCTACAGCCACCATG | GCCTGTGGAACTGCTGTGC | M23442 |

| IL-6 | GACCCAACCACAAATGCCA | GTCATGTCCTGCAGCCACTG | M14584 |

| IL-10 | GGTGATGCCCCAAGCTGA | TCCCCCAGGGAGTTCACA | U16720 |

| IL-12 p40 | CGGTCATCTGCCGCAAA | CAAGATGAGCTATAGTAGCGGTCCT | M65272 |

| IFN-α | GGTGCTCAGCTGCAAGTCAA | GCTACCCAGGCTGTGGGTT | J00207 |

| IFN-β | CAGCAATTTTCAGTGTCAGAAGC | TCATCCTGTCCTTGAGGCAGT | M28622 |

| IFN-γ | CCAACGCAAAGCAATACATGA | CGCTTCCCTGTTTTAGCTGC | J00219 |

| TNF | GGTGCTTGTTCCTCAGCCTC | CAGGCAGAAGAGCGTGGTG | M10988 |

| β-defensin-1 | GCAGTGGAGGGCAATGTCTC | TTCCCTCTGTAACAGGTGCCTT | NM_005218 |

| β-defensin-2 | TGATGCCTCTTCCAGGTGTTT | GGATGACATATGGCTCCACTCTTA | AF040153 |

| β-defensin-3 | TTATTGCAGAGTCAGAGGCGG | CGAGCACTTGCCGATCTGTT | AF516673 |

| α-defensin-1 | TCCCAGAAGTGGTTGTTTCCC | TCCTTGAGCCTGGATGCTTT | NM_004084 |

| TLR1 | CTGGTATCTCAGGATGGTGTGC | TTGGAGTTCTTCTAAGGGTATGTTCC | NM_003263 |

| TLR2 | GGCCAGCAAATTACCTGTGTG | AGGCGGACATCCTGAACCT | NM_003264 |

| TLR3 | TCCCAAGCCTTCAACGACTG | TGGTGAAGGAGAGCTATCCACA | NM_003265 |

| TLR4 | CTGCAATGGATCAAGGACCA | TTATCTGAAGGTGTTGCACATTCC | XM_057452 |

| TLR5 | TCGAGCCCCTACAAGGGAA | CACTGAGACTCTGCTATACAAGCTA | NM_003268 |

| TLR6 | CTATTGTTAAAAGCTTCCATTTTGT | ACCTGAAGCTCAGCGATGTAGTTC | NM_006068 |

| TLR7 | TTACCTGGATGGAAACCAGCTAC | TCAAGGCTGAGAAGCTGTAAGCTA | NM_016562 |

| TLR8 | GAGAGCCGAGACAAAAACGTTC | TGTCGATGATGGCCAATCC | NM_016610 |

| TLR9 | TGGTGTTGAAGGACAGTTCTCTC | CACTCGGAGGTTTCCCAGC | NM_017442 |

| TLR10 | GAAAGGTTCCCGCAGACTTG | TGGAGTTGAAAAAGGAGGTTATAG | NM_030956 |

| β2-microglobulin | CTCCGTGGCCTTAGCTGTG | TTTGGAGTACGCTGGATAGCCT | AF072097 |

Human mRNA . | Forward primer . | Reverse primer . | Accession no. . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL1/GRO-α | ACGTGAAGTCCCCCGGAC | GCCCATTCTTGAGTGTGGCT | NM_001511 |

| CXCL8/IL-8 | CTGGCCGTGGCTCTCTTG | CCTTGGCAAAACTGCACCTT | NM_000584 |

| CXCL9/MIG | TGCAAGGAACCCCAGTAGTGA | GGTGGATAGTCCCTTGGTTGG | NM_002416 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | TGAAATTATTCCTGCAAGCCAA | CAGACATCTCTTCTCACCCTTCTTT | NM_001565 |

| CXCL11/I-TAC | CAAGGCTTCCCCATGTTCA | CCACTTTCACTGCTTTTACCCC | NM_005409 |

| CXCL13/BCA | GACGCTTCATTGATCGAATTCA | TTCCAGACTATGATTTCTTTTCTTGG | NM_006419 |

| CCL2/MCP-1 | CTCTGCCGCCCTTCTGTG | TGCATCTGGCTGAGCGAG | NM_002982 |

| CCL3/MIP-1α | AGCTGACTACTTTGAGACGAGCA | CGGCTTCGCTTGGTTAGGA | NM_002983 |

| CCL4/MIP-1β | CTGCTCTCCAGCGCTCTCA | GTAAGAAAAGCAGCAGGCGG | NM_002984 |

| CCL5/RANTES | GACACCACACCCTGCTGCT | TACTCCTTGATGTGGGCACG | NM_002985 |

| CCL19/MIP-3β | GGCACCAATGATGCTGAAGA | GAAGTTCCTCACGATGTACCCAG | NM_006274 |

| CCL20/MIP-3α | TCCTGGCTGCTTTGATGTCA | TCAAAGTTGCTTGCTGCTTCTG | NM_004591 |

| IL-1β | ACGAATCTCCGACCACCACT | CCATGGCCACAACAACTGAC | M15330 |

| IL-4 | GGCAGTTCTACAGCCACCATG | GCCTGTGGAACTGCTGTGC | M23442 |

| IL-6 | GACCCAACCACAAATGCCA | GTCATGTCCTGCAGCCACTG | M14584 |

| IL-10 | GGTGATGCCCCAAGCTGA | TCCCCCAGGGAGTTCACA | U16720 |

| IL-12 p40 | CGGTCATCTGCCGCAAA | CAAGATGAGCTATAGTAGCGGTCCT | M65272 |

| IFN-α | GGTGCTCAGCTGCAAGTCAA | GCTACCCAGGCTGTGGGTT | J00207 |

| IFN-β | CAGCAATTTTCAGTGTCAGAAGC | TCATCCTGTCCTTGAGGCAGT | M28622 |

| IFN-γ | CCAACGCAAAGCAATACATGA | CGCTTCCCTGTTTTAGCTGC | J00219 |

| TNF | GGTGCTTGTTCCTCAGCCTC | CAGGCAGAAGAGCGTGGTG | M10988 |

| β-defensin-1 | GCAGTGGAGGGCAATGTCTC | TTCCCTCTGTAACAGGTGCCTT | NM_005218 |

| β-defensin-2 | TGATGCCTCTTCCAGGTGTTT | GGATGACATATGGCTCCACTCTTA | AF040153 |

| β-defensin-3 | TTATTGCAGAGTCAGAGGCGG | CGAGCACTTGCCGATCTGTT | AF516673 |

| α-defensin-1 | TCCCAGAAGTGGTTGTTTCCC | TCCTTGAGCCTGGATGCTTT | NM_004084 |

| TLR1 | CTGGTATCTCAGGATGGTGTGC | TTGGAGTTCTTCTAAGGGTATGTTCC | NM_003263 |

| TLR2 | GGCCAGCAAATTACCTGTGTG | AGGCGGACATCCTGAACCT | NM_003264 |

| TLR3 | TCCCAAGCCTTCAACGACTG | TGGTGAAGGAGAGCTATCCACA | NM_003265 |

| TLR4 | CTGCAATGGATCAAGGACCA | TTATCTGAAGGTGTTGCACATTCC | XM_057452 |

| TLR5 | TCGAGCCCCTACAAGGGAA | CACTGAGACTCTGCTATACAAGCTA | NM_003268 |

| TLR6 | CTATTGTTAAAAGCTTCCATTTTGT | ACCTGAAGCTCAGCGATGTAGTTC | NM_006068 |

| TLR7 | TTACCTGGATGGAAACCAGCTAC | TCAAGGCTGAGAAGCTGTAAGCTA | NM_016562 |

| TLR8 | GAGAGCCGAGACAAAAACGTTC | TGTCGATGATGGCCAATCC | NM_016610 |

| TLR9 | TGGTGTTGAAGGACAGTTCTCTC | CACTCGGAGGTTTCCCAGC | NM_017442 |

| TLR10 | GAAAGGTTCCCGCAGACTTG | TGGAGTTGAAAAAGGAGGTTATAG | NM_030956 |

| β2-microglobulin | CTCCGTGGCCTTAGCTGTG | TTTGGAGTACGCTGGATAGCCT | AF072097 |

Flow cytometry

Surface expression of various markers was assessed using CellQuest analysis software on a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) flow cytometer. Surface expression was determined using the following fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies: CD62L-PE (PharMingen, San Diego, CA), TLR1-PE, TLR2-PE, TLR4-PE, TLR9-PE, CD16-FITC (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), CXCR1-PE, and CXCR2-PE (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

L-selectin shedding

Neutrophils were isolated and stimulated as described above for 1 hour. Cells were harvested and stained with monoclonal antibody (mAb) for L-selectin (CD62L) and isotype control in parallel. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Superoxide generation

Neutrophils were isolated as described above at 106 cells per milliliter and treated with 50 ng/mL GM-CSF for 90 minutes, followed by TLR agonist stimulation for 30 minutes; 100 μL of the cells was added to 96-well culture plates. The cells were diluted 1:1 with media containing 50 μM cytochrome c (Sigma), with or without 0.1 μM fMLF (Sigma), with or without 60 U/mL superoxide dismutase (SOD; Sigma). The cells were incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes. The cells were then chilled on ice, centrifuged, and 150 μL of the supernatant recovered for measurements of absorbance at 550 nm. SOD-inhibitable superoxide generation is expressed as follows: (A550 without SOD - A550 with SOD).

Chemotaxis

Neutrophils were prepared as above at 106 cells per milliliter. Cells were diluted 1:1 with 2.5 μM BCECF-AM (2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6-)-carboxyfluorescein, acetoxymethyl ester) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in RPMI 1640 and subject to TLR agonists or GM-CSF for 1 hour at 37°C. Next, the cells were washed twice and resuspended at 5 × 105 cells per milliliter in chemotaxis media (RPMI 1640, 1% bovine serum albumin). Chemotaxis assays were performed on plastic chemotaxis chambers (Neuro Probe, Gaithersburg, MD; no. 106-5) containing 100 ng/mL IL-8 in chemotaxis media in the lower chamber and 20 μL of the neutrophil suspension (10 000 cells total). The chamber was then placed in a tissue-culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 1 hour. Cells that had transmigrated to the bottom chamber were counted using a Cytofluor fluorescence plate reader (480 nm excitation, 530 nm emission) and cell numbers were quantitated using a standard curve. Results were confirmed by manual count of at least one of the triplicate wells in each group.

Phagocytosis assay

Latex beads (1 μM polystyrene, carboxylate modified, red fluorescent biotin labeled) were opsonized with 1 mg/mL antibiotin immunoglobulin G (IgG) and human AB serum for 1 hour at 37°C. Next, they were washed 2 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The opsonized latex beads were then added to suspended neutrophils at a ratio of 25:1 and placed at 4°C to determine binding or 37°C to initiate phagocytosis. The samples were washed twice in PBS by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes. After washing, the samples were fixed with 10% formalin and viewed with a Nikon fluorescent microscope or analyzed by flow cytometry. The data are expressed as the percentage of cells that had internalized at least one latex bead (percent phagocytic) as well as by the number of internalized latex beads per 100 phagocytes × 100 (phagocytic index).

Results

TLR expression in freshly isolated human neutrophils

TLRs are important innate immune receptors, and the early innate immune response involves the influx of neutrophils. To determine the expression of TLRs in freshly isolated human neutrophils, we performed flow cytometry and quantitative PCR.

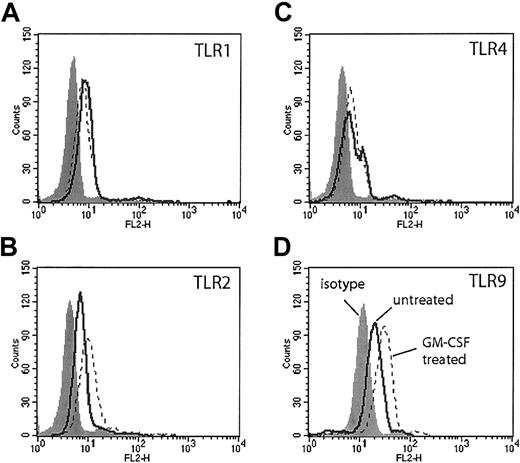

Flow cytometry with commercially available antibodies to TLRs 1, 2, 4, and 9 demonstrated modest expression of these TLRs in freshly isolated human neutrophils (Figure 1, solid lines). Cells stained for TLR9 were first permeabilized, because TLR9 is expressed in intracellular vesicles.8 GM-CSF treatment for 90 minutes resulted in a modest increase in TLR2 staining as previously described (Figure 1B, dotted line). We also observed a similar increase in TLR9 staining following GM-CSF treatment (Figure 1D, dotted line). There was no increase in the staining of TLR4 or TLR1 following GM-CSF treatment (Figure 1A,C, dotted line).

TLR expression on human neutrophils measured by flow cytometry. Human neutrophils were incubated in RPMI 1640 with or without GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 90 minutes. Cells were stained with antibodies specific for human TLR1 (A), TLR2 (B), TLR4 (C), and TLR9 (D) (solid lines indicate untreated; dotted lines, GM-CSF treated) or their isotype controls (gray histogram). Neutrophils stained with antibodies to TLR9 were first permeabilized. Representative of experiments performed on 3 donors.

TLR expression on human neutrophils measured by flow cytometry. Human neutrophils were incubated in RPMI 1640 with or without GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 90 minutes. Cells were stained with antibodies specific for human TLR1 (A), TLR2 (B), TLR4 (C), and TLR9 (D) (solid lines indicate untreated; dotted lines, GM-CSF treated) or their isotype controls (gray histogram). Neutrophils stained with antibodies to TLR9 were first permeabilized. Representative of experiments performed on 3 donors.

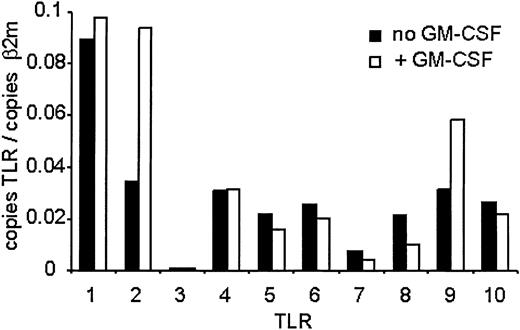

Because antibodies for flow analysis of other TLRs were not available, we measured expression using quantitative real-time PCR (QPCR) using specific primers to each TLR (Figure 2). QPCR analysis revealed expression of TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10 and low expression of TLR7. There was no expression of TLR3. GM-CSF pretreatment resulted in about 2.5-fold increase in TLR2 message levels and about 2-fold increase in TLR9 levels. No other TLR mRNA increased following treatment, while the mRNAs of TLRs 5, 6, 7, 8, and 10 decreased to varying extents. These results reveal an increase in both mRNA and protein levels of TLR2 and TLR9 in freshly isolated human neutrophils following GM-CSF treatment.

TLR expression on human neutrophils measured by QPCR. Human neutrophils were isolated and treated with GM-CSF as described in Figure 1. RNA was harvested from the cells, and mRNA levels for the TLRs were determined by QPCR and are depicted as the number of copies of the gene per copies of the control mRNA β2-microglobulin. Representative of experiments performed on 3 donors.

TLR expression on human neutrophils measured by QPCR. Human neutrophils were isolated and treated with GM-CSF as described in Figure 1. RNA was harvested from the cells, and mRNA levels for the TLRs were determined by QPCR and are depicted as the number of copies of the gene per copies of the control mRNA β2-microglobulin. Representative of experiments performed on 3 donors.

We have also performed QPCR to determine the TLRs expressed on murine (C57BL/6) bone marrow-derived neutrophils and found that they also express all TLRs tested with the exception of TLR3 (data not shown).

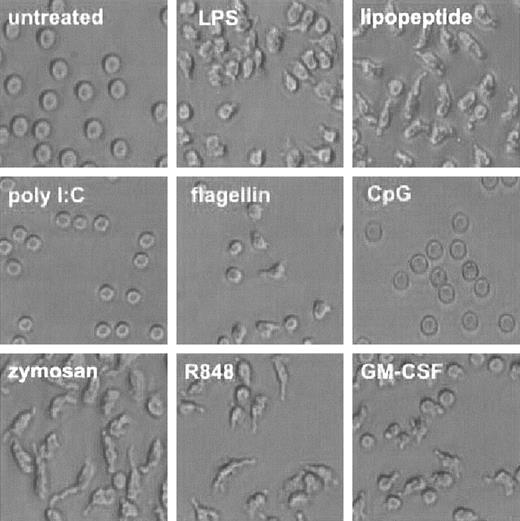

TLR function—alteration in cell shape

During the course of our investigation, we noted a dramatic change in the shape of neutrophils treated with TLR agonists (Figure 3). Human neutrophils maintained a round, phase-lucent appearance when cultured for 1 hour in plastic multiwell plates. Upon administration of TLR agonists for 1 hour, the neutrophils appeared to adhere loosely to the plastic and take on an asymmetrical appearance. Poly I:C, the agonist for TLR3, which is not expressed in these cells, failed to elicit a change in appearance. CpG DNA also did not elicit a change in cell shape, although we detected significant intracellular expression of TLR9, its cognate receptor. GM-CSF alone also elicited this change in appearance.

TLR agonists induce change in cell shape. Human neutrophils were isolated and treated with TLR agonists or GM-CSF as described in Figure 1. Cells were photomicrographed using phase contrast optics (original magnification, × 300). Representative of experiments performed on 3 donors.

TLR agonists induce change in cell shape. Human neutrophils were isolated and treated with TLR agonists or GM-CSF as described in Figure 1. Cells were photomicrographed using phase contrast optics (original magnification, × 300). Representative of experiments performed on 3 donors.

TLR function—IL-8 production

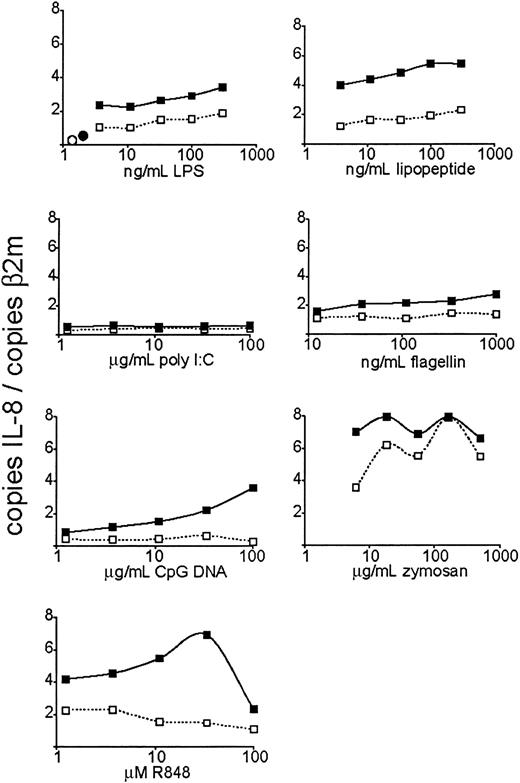

To measure TLR function in neutrophils and to be able to compare the response to various TLR stimuli, we first performed a dose response with agonists for TLR4 (lipopolysaccharide, or LPS9 ), TLR3 (poly I:C, a double-stranded RNA [dsRNA] analog10 ), TLR2/1 (Pam3CSK4, an artificial triacylated lipopeptide11-14 ), TLR5 (flagellin7 ), TLR7 and TLR8 (R848, an imidazoquinoline pharmaceutical compound15,16 ), TLR9 (nonmethylated CpG oligodeoxynucleotide17 ), and TLR2/6 (zymosan, an S cerevisiae cell wall particle18 ) and measured IL-8 mRNA expression after 3 hours of stimulation by quantitative real-time PCR (QPCR, Figure 4). Stimulation of TLRs 4, 2/1, 5, 7, 8, and 2/6 induced a robust, dose-responsive IL-8 mRNA accumulation. CpG DNA (TLR9 agonist) did not trigger an increase in IL-8 mRNA levels unless the cells were pretreated with GM-CSF. GM-CSF pretreatment also increased the magnitude of the IL-8 transcriptional response to the other active TLR stimuli, even in cases where GM-CSF did not increase the expression of the specific TLR mRNA. Poly I:C, the TLR3 agonist, did not trigger IL-8 mRNA increase regardless of GM-CSF pretreatment—a result consistent with the lack of TLR3 expression in neutrophils. IL-8 mRNA expression at the highest dose of R848 was reduced. This may be due to the cytotoxic effects of the carrier (DMSO). The dose responses of IL-8 mRNA transcription to stimulation dose were quite different between different stimuli—for instance, R848 demonstrating a steeper curve than flagellin. This may be due to a number of factors, such as bioavailability and stability of the stimuli in vitro, and differences in maximum signal strength between different TLRs (perhaps due to differences in receptor expression levels).

Dose-dependent induction of IL-8 expression by TLR agonists. Human neutrophils were isolated and stimulated at the indicated doses of TLR agonists. After 3 hours of TLR stimulation, the cells were harvested for RNA. Expression of IL-8 was determined by QPCR and depicted as the number of copies of IL-8 message per copies of the control mRNA β2-microglobulin. ○ indicates untreated cells; •, GM-CSF alone; □, cells treated with indicated TLR agonist; and ▪, cells pretreated with GM-CSF and treated with the indicated TLR agonist. Data are representative of 4 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

Dose-dependent induction of IL-8 expression by TLR agonists. Human neutrophils were isolated and stimulated at the indicated doses of TLR agonists. After 3 hours of TLR stimulation, the cells were harvested for RNA. Expression of IL-8 was determined by QPCR and depicted as the number of copies of IL-8 message per copies of the control mRNA β2-microglobulin. ○ indicates untreated cells; •, GM-CSF alone; □, cells treated with indicated TLR agonist; and ▪, cells pretreated with GM-CSF and treated with the indicated TLR agonist. Data are representative of 4 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

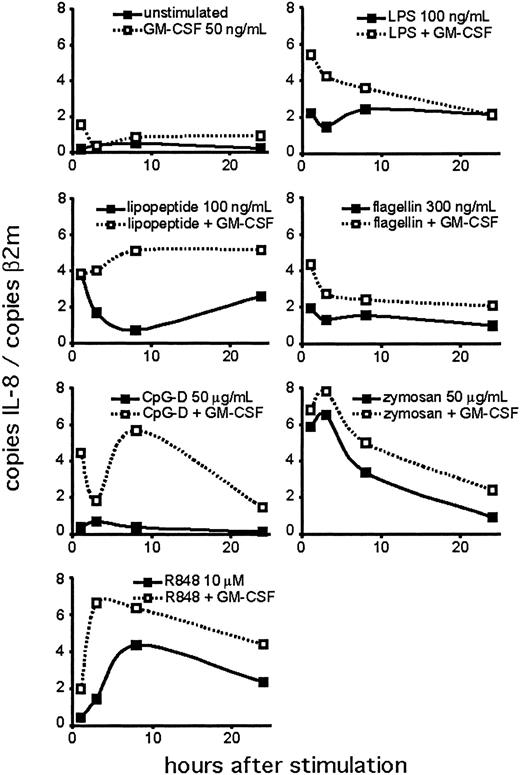

Next, we performed a time course experiment to determine the kinetics of the neutrophil response to TLR agonists (Figure 5). We detected IL-8 mRNA at the earliest time point tested (1 hour). In many cases, IL-8 mRNA was maximal at 1 to 3 hours, with levels persisting above untreated cells for the duration of the assay. This may reflect the continued stimulation of the TLRs during the course of the experiment. CpG treatment did not induce the production of IL-8 mRNA at any time point unless the neutrophils were pretreated with GM-CSF. IL-8 mRNA levels changed in different patterns for different agonists, although this may reflect the relative stability of the agonists in culture.

Time course of TLR agonist-induced IL-8 expression. Human neutrophils were isolated and stimulated, with or without 90 minutes of pretreatment with GM-CSF. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points for RNA. Expression of IL-8 was determined by QPCR and depicted as the number of copies of IL-8 message per copies of the control mRNA β2-microglobulin. Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

Time course of TLR agonist-induced IL-8 expression. Human neutrophils were isolated and stimulated, with or without 90 minutes of pretreatment with GM-CSF. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points for RNA. Expression of IL-8 was determined by QPCR and depicted as the number of copies of IL-8 message per copies of the control mRNA β2-microglobulin. Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

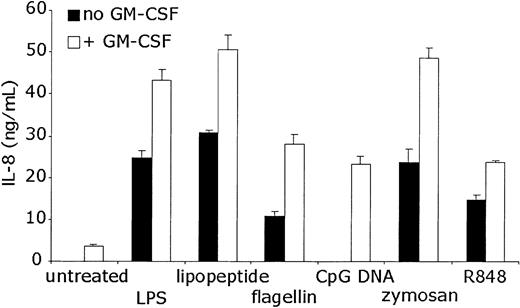

To determine whether the increases in IL-8 mRNA levels were accompanied by protein production, ELISA was performed on the supernatants of neutrophils stimulated with TLR agonists for 24 hours. The results were consistent with the RNA data (Figure 6). GM-CSF alone resulted in modest but measurable IL-8 production. TLR stimulation without GM-CSF pretreatment induced significant IL-8 protein production. GM-CSF pretreatment followed by TLR stimulation resulted in increased IL-8 protein levels over either stimulus alone. ELISA data again demonstrated that IL-8 protein production by CpG DNA treatment in neutrophils is completely dependent on GM-CSF pretreatment.

Measurement of TLR agonist-induced IL-8 protein production. Human neutrophils were stimulated as in Figure 4. Supernatants of the stimulated cells were collected after the cells were removed by centrifugation. ELISA was performed to detect human IL-8. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Data are representative of 5 similar experiments conducted on 3 donors.

Measurement of TLR agonist-induced IL-8 protein production. Human neutrophils were stimulated as in Figure 4. Supernatants of the stimulated cells were collected after the cells were removed by centrifugation. ELISA was performed to detect human IL-8. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Data are representative of 5 similar experiments conducted on 3 donors.

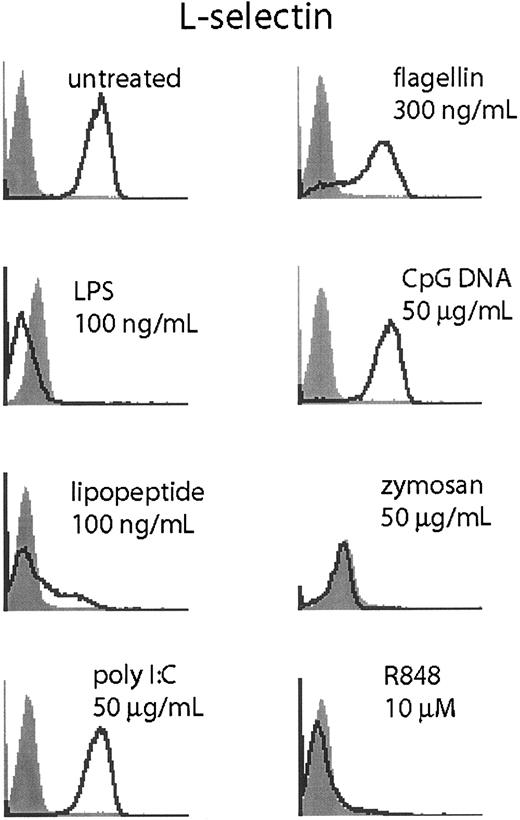

TLR stimulation triggers L-selectin shedding

Neutrophils shed L-selection upon activation through proteolytic cleavage.19,20 To determine if TLR stimulation could elicit L-selectin shedding in neutrophils, we measured L-selectin by flow cytometry following TLR stimulation (Figure 7).

TLR stimulation triggers L-selectin shedding. Human neutrophils were stimulated for 1 hour at the indicated doses of TLR agonist and harvested. Cells were stained for L-selectin (CD62L, open histogram) or isotype control (filled histogram). Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

TLR stimulation triggers L-selectin shedding. Human neutrophils were stimulated for 1 hour at the indicated doses of TLR agonist and harvested. Cells were stained for L-selectin (CD62L, open histogram) or isotype control (filled histogram). Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

Stimulation with LPS, lipopeptide, zymosan, and R848 triggered rapid (1 hour) and robust loss of surface L-selectin staining. Flagellin triggered L-selectin shedding in only a fraction of the cells, while poly I:C and CpG DNA did not affect L-selectin staining. We were unable to determine if GM-CSF costimulation or pretreatment would result in enhanced L-selectin cleavage because GM-CSF alone at doses as low as 200 pg/mL was sufficient to abolish L-selectin staining (data not shown).

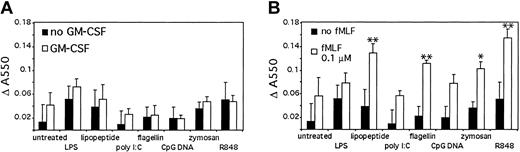

TLR signaling primes superoxide generation by fMLF

An important antimicrobial response of neutrophils is superoxide generation.21-24 Therefore, we tested superoxide generation after TLR stimulation (Figure 8A). Stimulation with TLR agonists alone elicited only modest superoxide dismutase (SOD)-inhibitable cytochrome c oxidation. There was a modest increase in measured superoxide production with GM-CSF pretreatment for LPS, lipopeptide, and zymosan.

TLR stimulation primes superoxide generation. (A) Human neutrophils were stimulated for 1 hour in the presence of cytochrome c, with or without 90 minutes of pretreatment with GM-CSF. Superoxide generation was determined by measuring SOD-inhibitable change in absorbance at 550 nm. (B) Human neutrophils were isolated and stimulated for 1 hour in the presence of cytochrome c. The cells were further stimulated with 0.1 μM fMLF for 15 minutes and superoxide generation determined as above. *P < .1, **P < .05, as determined by Student t test, compared with cells treated with fMLF alone. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

TLR stimulation primes superoxide generation. (A) Human neutrophils were stimulated for 1 hour in the presence of cytochrome c, with or without 90 minutes of pretreatment with GM-CSF. Superoxide generation was determined by measuring SOD-inhibitable change in absorbance at 550 nm. (B) Human neutrophils were isolated and stimulated for 1 hour in the presence of cytochrome c. The cells were further stimulated with 0.1 μM fMLF for 15 minutes and superoxide generation determined as above. *P < .1, **P < .05, as determined by Student t test, compared with cells treated with fMLF alone. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

Because the superoxide responses to TLR stimuli were modest, we next measured the ability of TLR agonists to prime subsequent fMLF stimulation (Figure 8B). The TLR agonists lipopeptide, flagellin, zymosan, and R848 primed neutrophils for subsequent fMLF-induced superoxide generation compared with neutrophils not given TLR agonists. LPS, poly I:C, and CpG DNA did not prime the neutrophils. This lack of priming by LPS has previously been described by Kurt-Jones et al.4

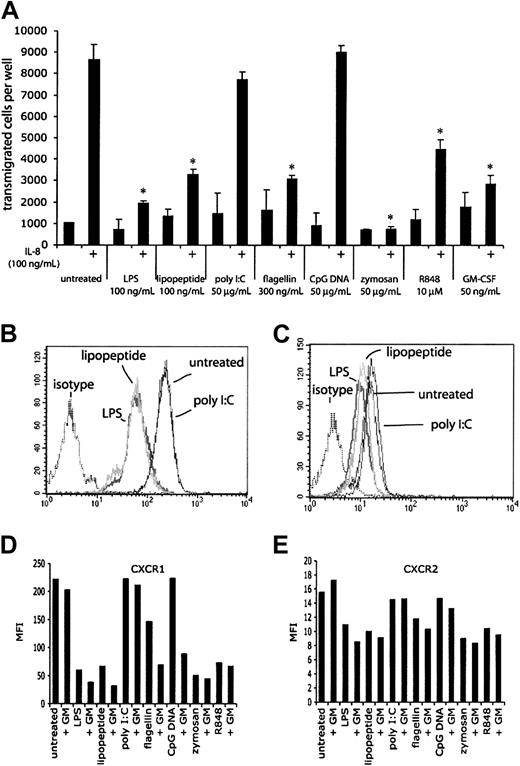

TLR stimulation reduces chemotaxis of neutrophils

The early infiltration of neutrophils at sites of infection suggests that chemotaxis is an important part of neutrophil function. To determine the effects of TLR stimulation on chemotaxis, neutrophils were stimulated with purified TLR agonists or GM-CSF for 1 hour, and their ability to chemotax to IL-8 (100 ng/mL) was measured (Figure 9A). After 1 hour, approximately 85% of freshly isolated neutrophils transmigrated in response to IL-8. Neutrophils that had been treated with GM-CSF displayed greatly reduced chemotaxis to IL-8, as did neutrophils that had been stimulated with LPS, lipopeptide, flagellin, and R848. Manual counts of the transmigrated cells gave similar results obtained by the fluorescent plate reader (data not shown). Neutrophils treated with poly I:C or CpG DNA did not display reduced chemotaxis to IL-8, consistent with the lack of response to these agonists in previous experiments. The ability of GM-CSF to make neutrophils responsive to CpG DNA could not be measured in this assay, because GM-CSF treatment alone inhibited chemotaxis. TLR stimulation or GM-CSF treatment did not significantly alter background chemokinesis (about 10% of input cells) in these experiments. The effect of zymosan on chemotaxis may not be solely attributed to signaling through TLRs, because the neutrophils were full of engulfed particles that could affect their ability to transmigrate across the filter. Because the neutrophils themselves make IL-8 in response to TLR agonists, a potential mechanism for this reduced chemotaxis may be due to receptor desensitization by autocrine IL-8 signaling. Although we measured robust IL-8 mRNA within 1 hour of TLR stimulation, we were unable to detect IL-8 protein in cell supernatants at this time point, suggesting that this mechanism is not likely (data not shown). Another mechanism by which TLR signaling inhibits IL-8-induced chemotaxis is the production of other chemokines (and nonprotein chemoattractants) by the stimulated neutrophils. Signals from one or more neutrophil-derived chemoattractants may be sufficient to desensitize CXCR1/2 without having levels of any one chemoattractant that is detectable by ELISA. Another possibility is that TLR signaling causes the production of other cytokines that may indirectly inhibit the response to IL-8. A fourth possible mechanism is an effect on surface CXCR1/2 expression following TLR stimulation. Indeed, LPS has been previously described to induce a loss of surface CXCR1/2 on neutrophils.25 We detected a loss of surface CXCR1 and CXCR2 staining after 2 hours of TLR stimulation (Figure 9B-E), suggesting that loss of surface chemokine receptor expression may help explain the reduction in chemotaxis to IL-8. The reduction in surface expression was accompanied by a reduction in the magnitude of Ca2+ flux in response to IL-8 but not fMLF, suggesting that the TLR effect is specific to CXCR1/2 (data not shown). Interestingly, GM-CSF treatment of neutrophils alone resulted in reduced chemotaxis to IL-8 without reduced surface expression of CXCR1 or CXCR2, suggesting that there may be additional mechanisms that contribute to the reduction in IL-8-induced chemotaxis following TLR stimulation.

TLR agonist-mediated effects on chemotaxis. (A) The ability of human neutrophils treated with TLR agonists to chemotax to IL-8 was measured in Neuro Probe chemotaxis chambers. Cells that had transmigrated through the filter were quantitated using a fluorescent plate reader. Microscopy and manual cell counts gave similar results. *P < .005, as determined by Student t test, compared with untreated cells responding to IL-8. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors. CXCR1 (B) and CXCR2 (C) expression on neutrophils was assessed by flow cytometry following 2 hours of stimulation with LPS, lipopeptide, and poly I:C. Isotype controls for treated cells were not significantly different from untreated cells. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) for expression of CXCR1 (D) and CXCR2 (E) of neutrophils following 2 hours of stimulation with the indicated TLR stimulus, with or without 90 minutes of pretreatment with GM-CSF.

TLR agonist-mediated effects on chemotaxis. (A) The ability of human neutrophils treated with TLR agonists to chemotax to IL-8 was measured in Neuro Probe chemotaxis chambers. Cells that had transmigrated through the filter were quantitated using a fluorescent plate reader. Microscopy and manual cell counts gave similar results. *P < .005, as determined by Student t test, compared with untreated cells responding to IL-8. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors. CXCR1 (B) and CXCR2 (C) expression on neutrophils was assessed by flow cytometry following 2 hours of stimulation with LPS, lipopeptide, and poly I:C. Isotype controls for treated cells were not significantly different from untreated cells. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) for expression of CXCR1 (D) and CXCR2 (E) of neutrophils following 2 hours of stimulation with the indicated TLR stimulus, with or without 90 minutes of pretreatment with GM-CSF.

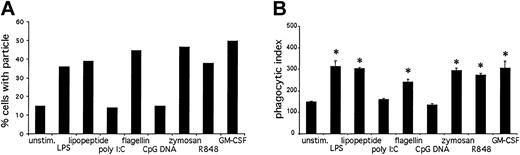

TLR stimulation increases neutrophil phagocytosis

Another important neutrophil immune function is the phagocytosis of foreign particles.26 To determine the effects of TLR stimulation on phagocytosis, we measured the ability of neutrophils to internalize opsonized latex particles (Figure 10). Stimulation with LPS, lipopeptide, flagellin, zymosan, R848, and GM-CSF resulted in an increase in phagocytosis as measured by flow cytometry (Figure 10A) as well as microscopy (Figure 10B). Poly I:C and CpG DNA had no effect on phagocytosis. We could not measure phagocytosis on GM-CSF-primed, CpG DNA-treated neutrophils, because GM-CSF alone enhanced phagocytosis.

TLR agonist-mediated effects on phagocytosis. Opsonized latex beads were incubated with prestimulated neutrophils at a ratio of 25:1 for 30 minutes at 37°C. Phagocytosis was measured by flow cytometry (A) and microscopy (B). Data are presented as percent of cells in the bead-positive gate (A) or number of internalized particles per 100 cells × 100 (B). *P < .01, as determined by Student t test, compared with untreated cells. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate samples. Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

TLR agonist-mediated effects on phagocytosis. Opsonized latex beads were incubated with prestimulated neutrophils at a ratio of 25:1 for 30 minutes at 37°C. Phagocytosis was measured by flow cytometry (A) and microscopy (B). Data are presented as percent of cells in the bead-positive gate (A) or number of internalized particles per 100 cells × 100 (B). *P < .01, as determined by Student t test, compared with untreated cells. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate samples. Data are representative of 3 similar experiments conducted on 2 donors.

Differential gene activation by TLRs in neutrophils

One of the prevailing thoughts about TLRs' role in immunity is that they identify the nature of the infection and help to tailor the subsequent immune reaction to best deal with the particular pathogen type. To determine if different TLR stimuli induce differential gene induction in neutrophils, we performed QPCR on neutrophils treated with different TLR stimuli and measured the transcriptional response for a number of chemokines and cytokines (Tables 2-3).

Differential gene induction by TLR agonists in neutrophils

TLR agonist inducible . | Constitutively expressed . | No/low expression . |

|---|---|---|

| IL-8 | IFN-α, -β, -γ | IL-4 |

| MIP-1α | TNF | IL-6 |

| MIP-1β | β-defensins-1, -2, -3 | IL-10 |

| MIP-3α | α-defensin-1 | MIG |

| GRO-α | MCP-1 | IP-10 |

| IL-1β | IL-12 p40 | I-TAC |

| RANTES | ||

| MIP-3β | ||

| BCA-1 |

TLR agonist inducible . | Constitutively expressed . | No/low expression . |

|---|---|---|

| IL-8 | IFN-α, -β, -γ | IL-4 |

| MIP-1α | TNF | IL-6 |

| MIP-1β | β-defensins-1, -2, -3 | IL-10 |

| MIP-3α | α-defensin-1 | MIG |

| GRO-α | MCP-1 | IP-10 |

| IL-1β | IL-12 p40 | I-TAC |

| RANTES | ||

| MIP-3β | ||

| BCA-1 |

Total RNA was isolated from primary human neutrophils (1 × 106 cells) stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL), lipopeptide (100 ng/mL), poly I:C (50 μg/mL), flagellin (300 ng/mL), CpG DNA (50 μg/mL), zymosan (50 μg/mL), R848 (10 μM), and GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 1 hour. Expression of chemokines and cytokines was quantified by QPCR. Table lists genes induced after TLR stimulation, genes expressed constitutively with no induction after TLR stimulation, and genes not expressed or expressed at very low levels with no induction after TLR stimulation.

Genes induced by TCR agonists in neutrophils

. | MIP-1α . | . | MIP-1β . | . | MIP-3α . | GRO-α . | . | IL-1β . | . | IL-8 . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.002 | (100) | 0.008 | (100) | 0.000 | 0.016 | (100) | 0.033 | (100) | 0.318 | (100) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.001 | (0.6) | 0.002 | (0.3) | 0.000 | 0.032 | (2.0) | 0.281 | (8.5) | 0.490 | (1.5) | |||||

| LPS | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.110 | (50.0) | 0.376 | (50.0) | 0.017 | 0.090 | (5.6) | 1.000 | (30.3) | 2.568 | (8.1) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.030 | (13.4) | 0.406 | (53.9) | 0.011 | 0.099 | (6.1) | 1.506 | (45.7) | 3.119 | (9.8) | |||||

| Lipopeptide | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.050 | (22.7) | 0.114 | (15.2) | 0.033 | 0.068 | (4.2) | 2.380 | (72.2) | 5.986 | (18.8) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.026 | (11.7) | 0.285 | (37.9) | 0.020 | 0.074 | (4.6) | 2.220 | (67.3) | 7.021 | (22.0) | |||||

| Poly I:C | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.004 | (1.9) | 0.008 | (1.0) | 0.000 | 0.013 | (0.8) | 0.031 | (1.0) | 0.562 | (1.8) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.002 | (0.9) | 0.003 | (0.4) | 0.000 | 0.041 | (2.6) | 0.351 | (10.7) | 0.510 | (1.6) | |||||

| Flagellin | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.045 | (20.6) | 0.104 | (13.9) | 0.020 | 0.053 | (3.3) | 0.323 | (9.8) | 1.516 | (4.8) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.015 | (7.0) | 0.197 | (26.2) | 0.000 | 0.075 | (4.7) | 1.816 | (55.1) | 4.283 | (13.5) | |||||

| CpG DNA | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.001 | (0.6) | 0.009 | (1.1) | 0.000 | 0.022 | (1.4) | 0.089 | (2.7) | 0.180 | (0.6) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.002 | (1.1) | 0.138 | (18.3) | 0.008 | 0.076 | (4.7) | 0.834 | (25.3) | 3.144 | (9.9) | |||||

| Zymosan | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.088 | (40.0) | 0.171 | (22.7) | 0.012 | 0.069 | (4.3) | 0.514 | (15.6) | 4.696 | (14.7) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.072 | (32.8) | 0.268 | (35.6) | 0.020 | 0.121 | (7.6) | 1.366 | (41.4) | 4.381 | (13.8) | |||||

| R848 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.210 | (95.3) | 0.299 | (39.8) | 0.015 | 0.072 | (4.5) | 0.889 | (27.0) | 1.987 | (6.2) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.305 | (138.5) | 0.525 | (69.7) | 0.023 | 0.096 | (6.0) | 2.130 | (64.6) | 6.735 | (21.1) | |||||

. | MIP-1α . | . | MIP-1β . | . | MIP-3α . | GRO-α . | . | IL-1β . | . | IL-8 . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.002 | (100) | 0.008 | (100) | 0.000 | 0.016 | (100) | 0.033 | (100) | 0.318 | (100) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.001 | (0.6) | 0.002 | (0.3) | 0.000 | 0.032 | (2.0) | 0.281 | (8.5) | 0.490 | (1.5) | |||||

| LPS | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.110 | (50.0) | 0.376 | (50.0) | 0.017 | 0.090 | (5.6) | 1.000 | (30.3) | 2.568 | (8.1) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.030 | (13.4) | 0.406 | (53.9) | 0.011 | 0.099 | (6.1) | 1.506 | (45.7) | 3.119 | (9.8) | |||||

| Lipopeptide | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.050 | (22.7) | 0.114 | (15.2) | 0.033 | 0.068 | (4.2) | 2.380 | (72.2) | 5.986 | (18.8) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.026 | (11.7) | 0.285 | (37.9) | 0.020 | 0.074 | (4.6) | 2.220 | (67.3) | 7.021 | (22.0) | |||||

| Poly I:C | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.004 | (1.9) | 0.008 | (1.0) | 0.000 | 0.013 | (0.8) | 0.031 | (1.0) | 0.562 | (1.8) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.002 | (0.9) | 0.003 | (0.4) | 0.000 | 0.041 | (2.6) | 0.351 | (10.7) | 0.510 | (1.6) | |||||

| Flagellin | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.045 | (20.6) | 0.104 | (13.9) | 0.020 | 0.053 | (3.3) | 0.323 | (9.8) | 1.516 | (4.8) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.015 | (7.0) | 0.197 | (26.2) | 0.000 | 0.075 | (4.7) | 1.816 | (55.1) | 4.283 | (13.5) | |||||

| CpG DNA | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.001 | (0.6) | 0.009 | (1.1) | 0.000 | 0.022 | (1.4) | 0.089 | (2.7) | 0.180 | (0.6) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.002 | (1.1) | 0.138 | (18.3) | 0.008 | 0.076 | (4.7) | 0.834 | (25.3) | 3.144 | (9.9) | |||||

| Zymosan | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.088 | (40.0) | 0.171 | (22.7) | 0.012 | 0.069 | (4.3) | 0.514 | (15.6) | 4.696 | (14.7) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.072 | (32.8) | 0.268 | (35.6) | 0.020 | 0.121 | (7.6) | 1.366 | (41.4) | 4.381 | (13.8) | |||||

| R848 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 0.210 | (95.3) | 0.299 | (39.8) | 0.015 | 0.072 | (4.5) | 0.889 | (27.0) | 1.987 | (6.2) | |||||

| Plus GM-CSF | 0.305 | (138.5) | 0.525 | (69.7) | 0.023 | 0.096 | (6.0) | 2.130 | (64.6) | 6.735 | (21.1) | |||||

Data are presented as copies of mRNA over copies of β2-microglobulin. Parentheses indicate fold induction over untreated.

We found that TLR agonists induced only a subset of chemokines and cytokines in neutrophils that we and others have reported to be up-regulated in human dendritic cells after TLR stimulation.27 Neutrophils stimulated with TLR agonists expressed chemokines active on monocytes/natural killer (NK) cells (MIP-1α/CCL3, MIP-1β/CCL4), neutrophils (IL-8/CXCL8, GRO-α/CXCL1), and immature dendritic cells (MIP-3α/CCL20). These chemokines were previously reported to be expressed in neutrophils,28-35 implying that neutrophils participate in the recruitment of innate immune cells to sites of infection. Some genes were not inducible but were constitutively expressed such as the Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-12 p40), and α/β-defensins. Other genes demonstrated no or low expression regardless of TLR stimulation, such as chemokines active on T cells (MIG/CXCL9, IP-10/CXCL10, I-TAC/CXCL11), B cells (BCA-1/CXCL13), mature dendritic cells (MIP-3β/CCL19), and the Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-10). Chemokines that attract T or B cells were not induced in stimulated neutrophils, suggesting that neutrophils on their own do not induce the migration of acquired immune cells to sites of infection. Furthermore, we found an essentially identical pattern of chemokines and cytokines produced by neutrophils regardless of with which TLR agonists they are treated (unlike dendritic cells27 ), suggesting that neutrophils do not instruct the acquired immune system to tailor the response to suit the type of infection encountered.

Consistent with our previous experiments, poly I:C or CpG DNA stimulation did not induce cytokine or chemokine expression in neutrophils. Again, GM-CSF pretreatment restored the ability of CpG DNA to induce gene expression.

Discussion

In this report, we describe the expression and function of the known TLRs in freshly isolated human neutrophils. TLR signaling is an important factor in host defense,36 and our data suggest that TLR function in neutrophils is a significant contributor to their importance. Our study provides a comprehensive set of data for TLR stimulation in human neutrophils that confirms and extends results reported by others.4,37 Our result showing increases in TLR2 message after GM-CSF treatment agrees with that of Kurt-Jones et al,4 while our result demonstrating TLR4 expression in neutrophils agrees with Muzio et al.38 In a manner similar to TLR2, we observed an increase in TLR9 staining and mRNA levels following GM-CSF treatment. We also demonstrate expression and functions of TLRs 1, 5, 6, 7, and 8 in human neutrophils and demonstrate that GM-CSF also increases the magnitude of the response to agonists for these receptors.

Although largely replaced with G-CSF, GM-CSF has been used in the past to treat patients with prolonged neutropenia to prevent infectious complications.39 Although there is no doubt that the efficacy of this treatment is in part due to GM-CSF's ability to increase neutrophil numbers, our data also suggest that GM-CSF's ability to enhance neutrophil responses to TLR stimulation may also contribute to the efficacy of this treatment.

Freshly isolated circulating neutrophils express all known TLRs with the exception of TLR3. Although not usually associated with viral infections, neutrophilia is associated with certain respiratory viral infections.40-42 TLR3-mediated recognition of double-stranded RNA is a potential mechanism of identifying viruses and viral infections, yet neutrophils do not express this receptor and are unresponsive to double-stranded RNA. It is unclear by which mechanism neutrophils would directly recognize virally infected host cells.

In a previous report, Kurt-Jones et al4 described the synergistic effect of GM-CSF treatment prior to TLR2 stimulation. This was explained by the increased expression of TLR2 after GM-CSF treatment. We also observed increased TLR2 as well as TLR9 expression after GM-CSF treatment. However, we feel that increased receptor expression alone does not completely explain the enhanced response to TLR stimulation following GM-CSF treatment because GM-CSF pretreatment also results in the enhancement of responses through TLRs whose expression does not increase following pretreatment. It is likely that effects other than increased receptor expression, such as altered localization or activation of signaling molecules, also play a role in TLR/GM-CSFR synergy. We do not rule out the contribution of increased receptor expression, and our data suggest that it does plays a role, because the GM-CSF-mediated increase on TLR2 and TLR9 responses is larger than that of the other TLRs. Kurt-Jones et al also described a lack of priming of superoxide generation by LPS. We also see little to no priming by LPS, though LPS on its own was able to trigger a modest superoxide response. This suggests that the reports in the literature regarding the ability of LPS to prime superoxide responses may be due to lipopeptide contamination frequently found in commercial LPS preparations.

Whereas TLR2-mediated signaling results in a weak response that can be increased with GM-CSF pretreatment, the TLR9-mediated recognition of CpG DNA is essentially nonexistent without pretreatment. Why this exquisite dependence on GM-CSF priming exists only for TLR9-mediated signals is unclear, though it is tempting to speculate that endogenous ligands for TLR9 (CpG DNA) are more prevalent than endogenous ligands for other TLRs, and thus the response must be tightly regulated. A potential mechanism for this GM-CSF induciblity of TLR9 function arises from the subcellular localization of TLR9 compared with the other TLRs—while other TLRs have access to the external environment through their plasma membrane localization, TLR9 is expressed in intracellular vesicles. GM-CSF's ability to up-regulate phagocytosis (and perhaps pinocytosis) would allow TLR9 to recognize internalized hypomethylated CpG DNAs. This suggests that fluid phase uptake of DNA is nonexistent in unstimulated neutrophils and is increased following GM-CSF treatment—a possibility that we are currently investigating.

Two important neutrophil functions, chemotaxis and phagocytosis, have been described to be influenced by TLRs. Although we have not been able to demonstrate a direct role for TLRs in either of these functions, we have been able to demonstrate a reduction in chemotaxis to IL-8 and an increase in the phagocytosis of opsonized latex beads upon TLR stimulation in neutrophils. The reduction of chemotaxis is reminiscent of the defect in neutrophil chemotaxis found in patients with sepsis43,44 and suggests this may be due to TLR stimulation of circulating neutrophils. It is tempting to speculate that reduction in neutrophil migration into sites of infection following sepsis-induced TLR stimulation contributes to the complications, including secondary infections, seen in septic patients. Overall, these findings are consistent with the notion that once neutrophils are in the presence of a pathogen, there is less need for that neutrophil to continue to migrate in response to inflammatory chemokines and rather a need for antimicrobial functions, such as phagocytosis, superoxide generation, and the production of cytokines and chemokines.

Our results regarding chemotaxis do not replicate results recently published by Fan and Malik describing an increase in chemotaxis following TLR4 stimulation.5 We have repeated our experiments using the higher cell numbers, higher LPS concentration, higher IL-8 concentration, and longer incubation times used by Fan et al, and we continue to detect reduced chemotaxis to IL-8 in TLR-agonist treated neutrophils (data not shown). The differences in the findings may be due to differences in the chemotaxis protocols used in the 2 laboratories, because we count cells that have migrated through the filter to the lower chamber while Fan et al have counted cells adhered to the filter. Because we observe up to 80% of the input cells migrating to the lower chamber, we are unsure of the significance of counting only those cells that have adhered to the filter. Additionally, our results are consistent with the previously described chemotactic defects seen in neutrophils from patients with sepsis43,44 as well as in neutrophils treated in vitro25 with LPS or neutrophils from mice treated systemically45 with LPS.

Our QPCR experiments demonstrated expression of innate immune chemokines by neutrophils. This is consistent with the concept that once neutrophils migrate to sites of infection, they simultaneously conduct antimicrobial functions while producing chemokines to trigger migration of other immune cells, such as more neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, NK cells, and immature dendritic cells. Interestingly, neutrophils stimulated with TLR agonists do not express chemokines that induce migration of T or B cells, in marked contrast to TLR stimulation on dendritic cells. There has been a previous report demonstrating the production of the T-cell-attracting chemokines IP-10, I-TAC, and MIG in neutrophils stimulated with LPS, but this required costimulation with interferon-γ (IFN-γ).46 This would allow neutrophils to participate in the production of these chemokines in the presence of IFN-γ-producing cells, but TLR stimulation alone does not trigger the production of these chemokines in neutrophils.

A popular hypothesis to explain the existence of multiple TLRs in mammalian genomes is that they allow the innate immune system to identify the class of pathogen encountered in order to subsequently tailor the immune response to best deal with that pathogen.2 A key prediction of this hypothesis is differential responses to stimulation of different TLRs. We have previously reported a difference between TLR4 and TLR5 signaling in human dendritic cells (DCs),27 which was due to autocrine signals from type 1 interferons. We detect no significant differences in gene induction following stimulation of neutrophils with different TLR agonists, suggesting neutrophils on their own do not participate in the “classification” of pathogens and subsequent tailoring of the immune response. However, this does not rule out the possibility that classification of pathogens by TLRs is determined by the response of different cell types, each expressing a different pattern of TLRs. Although the stimulation of any TLR on a single cell type may result in the same response, each class of pathogen could stimulate a different set of host cells, thereby eliciting a different set of immune responses evolutionarily tailored to deal with that pathogen.

The ability of purified TLR agonists to activate neutrophil functions strongly suggests that TLRs are an important pattern recognition receptor in the function of neutrophils. In this report, we have demonstrated that neutrophils express TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. TLR stimulation on neutrophils can result in the shedding of L-selectin, reduction in chemotaxis, increased phagocytosis, priming of superoxide generation, and the production of a number of cytokines and chemokines. Interestingly, many neutrophil functions can be elicited by purified TLR agonists recognized through specific TLRs, demonstrating that the cellular response to TLR stimulation is more varied than the initiation of proinflammatory gene expression or increase in T-cell costimulatory receptors. These results strongly suggest that TLRs are the primary pathogen recognition receptors on neutrophils.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 26, 2003; DOI 10 .1182/blood-2003-04-1078.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01-CA69212 and P01-DK50305 (A.D.L.), T32-AR07258 (F.H.), and T32-HL07874 (T.K.M.).

F.H. and T.K.M. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal