Abstract

Although the functions of granzymes A and B have been defined, the functions of the other highly expressed granzymes (Gzms) of murine cytotoxic lymphocytes (C, D, and F) have not yet been evaluated. In this report, we describe the ability of murine GzmC (which is most closely related to human granzyme H) to cause cell death. The induction of death requires its protease activity and is characterized by the rapid externalization of phosphatidylserine, nuclear condensation and collapse, and single-stranded DNA nicking. The kinetics of these events are similar to those caused by granzyme B, and its potency (defined on a molar basis) is also equivalent. The induction of death did not involve the activation of caspases, the cleavage of BID, or the activation of the CAD nuclease. However, granzyme C did cause rapid mitochondrial swelling and depolarization in intact cells or in isolated mitochondria, and this mitochondrial damage was not prevented by cyclosporin A pretreatment. These results suggest that granzyme C rapidly induces target cell death by attacking nuclear and mitochondrial targets and that these targets are distinct from those used by granzyme B to cause classical apoptosis.

Introduction

Although a large number of granzyme (Gzm) genes have been identified in the mouse (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, K, and M),1 the functions of only 2 of these enzymes (GzmA and GzmB) have been clearly defined.2-4 When either GzmA or GzmB is introduced into target cells with perforin, cell death is induced.5,6 However, the critical cellular substrates for these 2 enzymes are clearly different. Granzyme B (GzmB) is an aspase,7,8 and it is known to cleave and activate several caspases immediately upon target cell entry, including caspase-3 and -8.2 GzmB also cleaves ICAD, which leads to the activation of caspase-activated DNase (CAD).9,10 Finally, GzmB is known to cleave and activate BID, which translocates to the mitochondria and facilitates the organization of a mitochondrial pore created by BAX, BAK, or both, which is followed by cytochromec (cyt c) release and apoptosome assembly.11-16 GzmB can also induce rapid mitochondrial depolarization independently of BAX and BAK, in cooperation with an unknown cellular factor.16 Granzyme A (GzmA), on the other hand, is a tryptase, and its known substrates include histone H1,17 nuclear lamins,18 and SET, a nucleosome assembly protein that is part of a large endoplasmic reticulum-associated complex.19 The precise contributions of these substrates to GzmA-induced cell death are not yet clear.

Mice have more granzyme genes than humans. Although both species have Gzms A and K in tightly linked clusters,20 the genes linked with GzmB are different in the 2 species. In the human GzmB cluster, GzmB lies upstream of granzyme H (GzmH),21 which has chymase specificity.22 The mouse GzmB cluster is more complex. The GzmB gene lies upstream from Gzms C, F, G, D, and E (5′ → 3′).23 All the genes are in the same transcriptional orientation, and all are expressed in cytotoxic lymphocytes to varying extents. In cytotoxic T cells activated in vitro with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (or with one-way mixed-lymphocyte reactions), the predominant granzymes expressed are A and B. However, in lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cell preparations and natural killer (NK) cell lines, Gzms C, D, and F are also expressed at high levels, along with A and B.23 The patterns of granzyme gene expression with different in vivo activation protocols have not yet been clearly defined. Even though Gzms C, D, and F can be highly expressed, their functions are unknown, and we have therefore referred to these enzymes as the orphan granzymes.2

The human orphan granzyme GzmH lies just downstream from GzmB and is maximally expressed in the LAK/NK environment.24,25 The murine orphan granzyme gene most closely related to GzmH is GzmC, which is also the first gene found downstream from GzmB in the mouse genome.23 In this report, we show that GzmC is capable of causing cell death. It induces many features of target cell apoptosis in a reconstituted in vitro system, but several of these features are distinct from those produced by GzmB. GzmC does not cause target cell death by activating caspases, BID, or ICAD, but it does cause direct effects on mitochondria that lead to swelling and depolarization. Therefore, GzmC is a functional protease in the cytotoxic lymphocyte repertoire, inducing target cell death with a mechanism that is different from that of granzyme A or B.

Materials and methods

Recombinant granzymes and perforin purification

Recombinant GzmC (rGzmC) was synthesized in Pichia pastoris and purified as previously described for rGzmB.26 Mutant rGzmCSer184Ala was produced as described for rGzmBSer183Ala.9 rGzmC production was detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)/Western blot analysis.

Perforin was purified from murine NK cell line 37.12, derived from an NK lymphoma in transgenic mice containing the human GzmH promoter linked to simian virus 40 (SV40)–Tag.25 Frozen cell pellets (5 × 107 cells) were suspended in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 1.0% Triton-X 100), sonicated, and dialyzed twice for 1 hour in low-salt perforin buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid]) at 4°C. The lysate was centrifuged at 10 000g and loaded onto an Accell cation exchange column (Waters) for purification by affinity chromatography, eluting 1-mL fractions using a linear 0.2- to 0.8-M NaCl gradient. Fractions with lytic activity on sheep red blood cells were tested for tryptase and aspase activity using the colorimetric substrates BLT esterase and Box-Ala-Ala-Asp-SBzl, respectively.4,26 27 Granzyme-free perforin eluted at approximately 0.5 to 0.6 M NaCl. The granzyme-free fractions with perforin activity were pooled, filtered, and stored at 80°C.

Antibodies

Polyclonal rabbit antimouse GzmA and GzmB antibodies were previously described.4,28 The polyclonal rabbit anti-GzmC antibody was generated by immunization with a peptide (CESQFQSSYNRAN, residues 174-186); it does not react with LAK cell extracts from mice deficient in Gzms B, C, D, and F.23 Rat antihuman perforin (Kamiya Biomedical Company, Seattle, WA) was used to detect murine perforin.4

Cellular viability assay

YAC-1, EL4, TA3, and P815 cell lines were cultured in K5 media.29 Log-phase target cells were harvested, washed twice, and resuspended at 2 × 105/mL in prewarmed red blood cell (RBC) buffer (modified Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks balanced salt solution [HBSS] supplemented with 0.01 M HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-2-ethanesulfonic acid; pH 7.5] and 0.4% bovine serum albumin [BSA]). Recombinant granzyme (0-2 μM), 1 μg purified perforin, and Ca2+ (3.8 mM CaCl2and 0.81 mM MgSO4 in RBC buffer) were added sequentially to 105 target cells in a final volume of 100 μL at 37°C. In some experiments, this reaction was proportionally scaled up to increase the yield of treated target cells. As negative controls for every experiment, target cells were untreated or treated with perforin, rGzmB, or rGzmC alone. To assess cell viability, 105 YAC-1 (H-2a) cells were mixed with 0 to 1000 nM recombinant granzyme and purified perforin, incubated at 37°C for 1 hour, and plated in duplicate with limiting dilution in 96-well microplates that were incubated at 37°C for 14 days. As a surrogate marker for viability, 0.25 μg 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) was added to target cells at the end of the assay, and cells were evaluated with a FACScan flow cytometer and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–annexin V conjugate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to assess phosphatidylserine externalization. YAC-1 target cells (105 cells) were treated with perforin and 1 μM rGzm B or C and were incubated for 5, 15, 30, or 60 minutes at 37°C. The cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry as described.30

Caspase activity studies were performed as previously described.9 YAC-1 cells (2 × 105) were pretreated with 100 μM D-fmk or the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle for 30 minutes at 37°C. Next, cells were treated with 1 μM granzyme plus perforin and harvested after 5, 15, 30, or 60 minutes of incubation at 37°C. Lysates were prepared, and Ac-DEVD-AMC (acetyl-DEVD-7-amino-4-methyl coumarin) cleavage was measured using a Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA) HTS7000 spectrofluorometer.

Flow–TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) was performed with the ApopTag Fluorescein Direct In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Intergen, Purchase, NY), as described.9 YAC-1 cells were treated with perforin, and 1 μM rGzm B or C was treated for the times indicated. To assess DNA fragmentation, 2 × 105 YAC-1 cells were loaded with rGzmB or rGzmC (1 μM) and incubated for 1 or 2 hours at 37°C. Genomic DNA was extracted and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis as described.9 Genomic DNA was also radiolabeled in the Klenow 32P-dATP incorporation assay as previously described.31 Denatured DNA samples were subjected to alkaline agarose electrophoresis, and the dried gel was autoradiographed.

Immunofluorescence and light microscopy

YAC-1 target cells (105) were treated with perforin and 1 μM rGzm B or C and incubated at 37°C for 5, 15, 30, or 60 minutes. All cells (100μL) were immobilized onto a microscope slide with a cytospin apparatus (Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA) at 200 rpm for 3 minutes and were air dried for 10 minutes. Cells were treated with modified Wright-Giemsa stain (Sigma, St Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cyt c immunodetection was performed as previously described.16

Electron microscopy

YAC-1 target cells (2 × 105) were treated with perforin and 1 μM rGzm B or C for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed and fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer on ice for 30 minutes and were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. Embedding in Polybed 812 (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) and thin-sectioning on a Reichert-Jung ultra microtome (Vienna, Austria) were performed at the Electron Microscopy Facility (Department of Cell Biology and Physiology, Washington University School of Medicine). Images were viewed with a Zeiss EM 902 electron microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Recombinant BID and DFF45/ICAD cleavage

Recombinant BID, the rabbit polyclonal anti-BID antibody, recombinant human ICAD, and the anti-human ICAD antibody have been previously described.9,32 Recombinant proteins and granzymes were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EGTA (ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid). Proteins were then separated on SDS gels, and Western blot analysis was performed as described.16

Swelling and membrane potential of isolated mitochondria

Volumetric and membrane potential changes of mitochondria isolated by standard differential centrifugation from Balb/c mouse livers and incubated in experimental buffer (125 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-MOPS (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane–3-[N-Morpholino]propanesulphonic acid), 1 mM Pi, 5 mM glutamate, 2.5 mM malate, 10 μM EGTA-Tris [pH 7.4]) were performed as previously described.16

Release of mitochondrial matrix entrapped dyes

Mitochondria (10 mg/mL) were loaded with 10 μM calcein-AM (acetoxymethyl ester) or rhod-2-am for 30 minutes at 25°C in isolation buffer in the dark, washed, and resuspended in isolation buffer. Mitochondrial matrix esterases cleave the acetoxymethyl moiety, thereby generating the fluorescent calcein and rhod-2 that remain entrapped in the mitochondrial matrix.33 34 Calcein and rhod-2 are of 622.54 molecular weight (MW) and 869.06 MW, respectively. Loaded mitochondria (0.5 mg/mL) incubated in experimental buffer was treated as described in the legend to Figure 6. After 30 minutes, mitochondria were sedimented by centrifugation at 14 000g for 3 minutes. Calcein and rhod-2 fluorescence were measured in the pellet and in the supernatant at 25°C in a Perkin Elmer LS50B spectrofluorometer, with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 488 ± 5 and 540 ± 5 nm for calcein and 540 ± 5 and 580 ± 5 nm for rhod-2.

Real-time mitochondrial membrane potential imaging in situ

Real time Δψm imaging of wild-type murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) loaded with 10 nM tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) in the presence of the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein inhibitor verapamil was performed exactly as previously described.16 Images were stored and analyzed, and data were normalized as previously described.16

Results

GzmC can induce cell death

Recombinant mature GzmC (rGzmC) and attenuated GzmC (rGzmC-Ser184Ala, an active site serine-to-alanine point mutant) were expressed in P pastoris and purified by cation exchange chromatography.26 The comparable GzmB mutant, rGzmB-Ser183Ala, has attenuated proteolytic activity against a tetrapeptide substrate (Boc-Ala-Ala-Asp-SBzl) and its protein substrates caspase-3 and ICAD.9 Perforin was partially purified from the adherent NK cell line 37.12.25 The electrophoretic mobility and abundance of each purified enzyme was verified on silver-stained SDS-PAGE gels (Figure1A). The identity of perforin and the recombinant granzymes was confirmed by Western blot analysis. The partially purified perforin used in these studies did not contain detectable quantities of granzyme A, B, or C (Figure 1B). Because neither the peptide nor the protein substrates of murine rGzmC have been identified, no enzymatic assay for this protein is available. For this reason, all experiments comparing GzmB and GzmC were performed using equimolar amounts of these proteins.

Purification of recombinant granzymes and NK cell-derived perforin.

(A) Recombinant granzymes were produced and purified (0.5 μg), and equivalent amounts (1 μg) of rGzmA, rGzmB, rGzmBSer183Ala, rGzmC, and rGzmCSer184Ala were separated on an SDS-PAGE reducing gel and visualized by silver staining. (B) Western blots. NK cell line lysates (25 μg) and 0.5 μg of partially purified perforin, rGzmA, rGzmB, rGzmBSer183Ala, rGzmC, and rGzmCSer184Ala were electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE gels. Western blot analysis was performed using polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse GzmA, B, and C and the rat antihuman perforin antibody (1:2000 each).

Purification of recombinant granzymes and NK cell-derived perforin.

(A) Recombinant granzymes were produced and purified (0.5 μg), and equivalent amounts (1 μg) of rGzmA, rGzmB, rGzmBSer183Ala, rGzmC, and rGzmCSer184Ala were separated on an SDS-PAGE reducing gel and visualized by silver staining. (B) Western blots. NK cell line lysates (25 μg) and 0.5 μg of partially purified perforin, rGzmA, rGzmB, rGzmBSer183Ala, rGzmC, and rGzmCSer184Ala were electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE gels. Western blot analysis was performed using polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse GzmA, B, and C and the rat antihuman perforin antibody (1:2000 each).

A plating assay was performed to evaluate the clonogenic potential of cells treated with granzymes and perforin. Purified perforin efficiently traffics recombinant granzymes into target cells.9 YAC1 target cells were treated with purified perforin and each recombinant granzyme for 1 hour at 37°C. Subsequently, the cells were plated by limiting dilution and cultured for 2 weeks to allow for the outgrowth of individual cells so that clonogenic potential could be quantitated. Similar reductions in clonogenic potential were observed in target cells treated with perforin plus 50 nM rGzmB or C. In contrast, cells treated with perforin only or with each granzyme by itself caused no reduction in clonogenic potential. Granzyme protease activity was required for the induction of target cell death because the attenuated mutant granzymes (rGzmB-Ser183Ala and rGzmC-Ser184Ala) did not alter the clonogenic potential of treated cells (Figure 2A). Given that these mutations attenuate the activities of the proteases but do not eliminate them, high doses (greater than 500 nM) of the mutant enzymes also induce cell death, though less efficiently (data not shown).

Active recombinant GzmC delivered by perforin causes target cell death.

(A) Target cell viability. YAC1 cells were treated with a fixed dose of purified perforin (Pfn; 1 μg) or recombinant granzymes alone as negative controls. Cells were treated with 50 nM rGzmB, rGzmBSer183Ala, rGzmC, or rGzmCSer184Ala plus perforin and were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Next, samples were plated using limiting dilution in duplicate 96-well microplates and were incubated for 14 days at 37°C. The percentage of total plated cells that formed clones is plotted as the mean ± SEM. This experiment was repeated 4 times with similar results. (B) (top row) YAC1 cells (105) were treated with nothing, perforin, rGzmB, or rGzmC alone for 1 hour at 37°C. Forward scatter properties and 7-AAD staining were quantified by flow cytometry. (bottom rows) YAC1 cells, treated with perforin plus increasing doses of rGzmB or rGzmC for 1 hour at 37°C, were stained with 7-AAD and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Dose-response. (Left panel) Percentages of 7-AADlo target cells, obtained from panel C, are shown for increasing doses of granzymes. (Right panel) At the end of the 1-hour assay, target cells were plated in duplicate using limiting dilution. The percentage of total plated cells that yielded clones was quantified at 14 days. This experiment was repeated 4 times with similar results.

Active recombinant GzmC delivered by perforin causes target cell death.

(A) Target cell viability. YAC1 cells were treated with a fixed dose of purified perforin (Pfn; 1 μg) or recombinant granzymes alone as negative controls. Cells were treated with 50 nM rGzmB, rGzmBSer183Ala, rGzmC, or rGzmCSer184Ala plus perforin and were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Next, samples were plated using limiting dilution in duplicate 96-well microplates and were incubated for 14 days at 37°C. The percentage of total plated cells that formed clones is plotted as the mean ± SEM. This experiment was repeated 4 times with similar results. (B) (top row) YAC1 cells (105) were treated with nothing, perforin, rGzmB, or rGzmC alone for 1 hour at 37°C. Forward scatter properties and 7-AAD staining were quantified by flow cytometry. (bottom rows) YAC1 cells, treated with perforin plus increasing doses of rGzmB or rGzmC for 1 hour at 37°C, were stained with 7-AAD and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Dose-response. (Left panel) Percentages of 7-AADlo target cells, obtained from panel C, are shown for increasing doses of granzymes. (Right panel) At the end of the 1-hour assay, target cells were plated in duplicate using limiting dilution. The percentage of total plated cells that yielded clones was quantified at 14 days. This experiment was repeated 4 times with similar results.

Target cells loaded with rGzmB or C exhibited a dose-dependent loss of membrane integrity that was quantifiable with flow cytometry. The cell-impermeable molecule 7-AAD is a cytometric probe for cells with membrane damage.30 Flow cytometric analyses of YAC1 target cells are illustrated in dot plots comparing forward scatter (x-axis) and 7-AAD staining (y-axis). Untreated cells or those treated with perforin or granzymes alone are mostly large and viable (ie, forward scatterhi/7-AADlo) and are found in the lower right quadrant of the dot plot (Figure 2B, top row). YAC1 target cells treated with rGzmB and perforin became smaller and 7-AADhi. Comparable changes occurred with rGzmC, and equivalent enzyme concentrations of rGzmC caused similar effects. Both rGzmB and C are potent inducers of cell death—the delivery of perforin and 50 nM or 100 nM rGzmB or C results in fewer than 10% or 1% viable target cells, respectively (Figure 2C, right panel). In contrast, treatment of YAC1 cells with perforin and 1 or 3 μM purified human cathepsin G, neutrophil elastase, or proteinase 3 did not cause any changes in 7-AAD positivity (S. Raptis and T.J.L., unpublished, 2001).

Membrane damage measured with flow cytometry was also directly compared with clonogenic efficiency. As noted previously, the percentage of 7-AADlo YAC1 cells declined significantly after the addition of perforin and rGzm B or C (Figure 2C, left panel). The loss of membrane integrity after 1 hour of treatment correlated strongly with reduced clonogenic efficiency. However, at very low concentrations of granzymes, 7-AAD staining underestimated the loss of clonogenic efficiency, perhaps because some 7-AAD low cells were committed to die, but had not yet experienced membrane changes. Similar data were acquired using 3 other target cell lines (EL4, P815, TA3) and cultured (MEFs; data not shown). Combinations of rGzms B and C were also delivered to YAC-1 cells by fixing the dose of one (50 nM) and increasing the other (50-1000 nM). The 7-AAD changes induced by the 2 proteases were additive, suggesting that rGzmB and C activate independent pathways (data not shown).

Features of GzmC-induced death

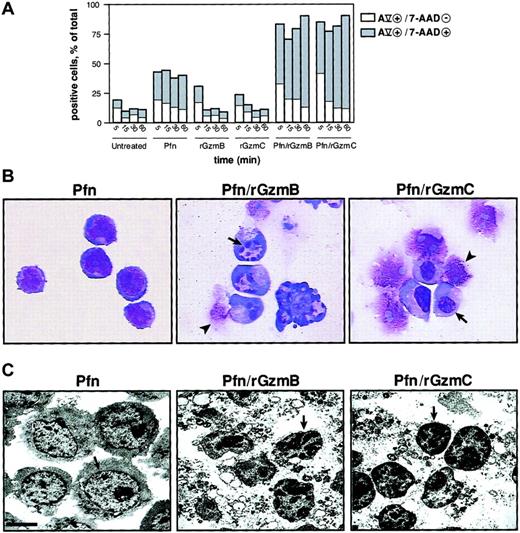

The membrane phospholipid phosphatidylserine (PS) translocates from the inner to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane in the early phase of apoptosis and precedes the loss of membrane integrity. Cells that are annexin Vhi and 7-AADlo indicate PS externalization in cells that are beginning to undergo apoptosis35; a significant percentage of YAC1 cells treated with perforin and rGzmB or C at 37°C for 5 minutes exhibited this staining pattern. At later time points, the proportion of cells at a later stage of apoptosis (ie, double-positive) was substantially expanded; these changes did not occur in untreated cells or in cells treated with rGzmB or C alone. However, perforin alone caused some cells to become annexin Vhi or 7-AADhi, or both, probably because of the limited membrane damage caused by this protein (Figure 3A). Nuclear condensation is a morphologic hallmark of apoptosis. Wright-Giemsa staining of YAC1 cells treated with perforin and rGzmB demonstrated GzmB-dependent nuclear collapse and fragmentation. The appearance of the condensed nuclei differed for rGzmC, however, because nuclear collapse was not accompanied by fragmentation in most cells (Figure 3A). Cells treated with perforin alone, rGzmB alone, or rGzmC alone were identical in appearance to untreated cells (Figure 3B and data not shown). Low magnification (× 2850) transmission electron microscopy revealed chromatin condensation induced by rGzmB or C. Nuclear condensation and chromatin clumping was not detected in untreated cells or in those treated with perforin alone or granzymes alone. Cytoplasmic vacuolization and disruption also occurred in cells treated with perforin plus GzmB or C (Figure 3C).

Phosphatidylserine externalization and nuclear condensation occur in GzmC-induced apoptosis.

(A) Percentage of target cells with single-positive annexin Vhi (AV) versus double-positive AVhi/7-AADhi staining. YAC1 target cells were treated with perforin and 1μM rGzmB or rGzmC at 37°C for 5, 15, 30, or 60 minutes. Additionally, target cells were exposed to nothing, perforin, rGzmB, or rGzmC alone. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) YAC1 cells were treated with perforin alone or perforin plus 1 μM rGzmB or rGzmC for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cell suspensions were immobilized onto microscope slides, stained by Wright-Giemsa, and visualized by light microscopy (× 100 magnification). Cells treated with perforin showed a normal morphologic appearance. Target cells that were untreated or treated with granzymes only resembled perforin-treated cells (data not shown). Nuclear collapse (arrows) was observed, as was late cell disruption (arrowheads). (C) Transmission electron microscopy of YAC1 cells incubated with perforin and granzymes as in panel B revealed chromatin condensation (arrows) and cytoplasmic disruption (bar represents 2.5 μm). Perforin-treated cells were identical to untreated cells or to cells treated with granzymes only (data not shown).

Phosphatidylserine externalization and nuclear condensation occur in GzmC-induced apoptosis.

(A) Percentage of target cells with single-positive annexin Vhi (AV) versus double-positive AVhi/7-AADhi staining. YAC1 target cells were treated with perforin and 1μM rGzmB or rGzmC at 37°C for 5, 15, 30, or 60 minutes. Additionally, target cells were exposed to nothing, perforin, rGzmB, or rGzmC alone. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) YAC1 cells were treated with perforin alone or perforin plus 1 μM rGzmB or rGzmC for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cell suspensions were immobilized onto microscope slides, stained by Wright-Giemsa, and visualized by light microscopy (× 100 magnification). Cells treated with perforin showed a normal morphologic appearance. Target cells that were untreated or treated with granzymes only resembled perforin-treated cells (data not shown). Nuclear collapse (arrows) was observed, as was late cell disruption (arrowheads). (C) Transmission electron microscopy of YAC1 cells incubated with perforin and granzymes as in panel B revealed chromatin condensation (arrows) and cytoplasmic disruption (bar represents 2.5 μm). Perforin-treated cells were identical to untreated cells or to cells treated with granzymes only (data not shown).

GzmC induces DNA nicking during the induction of cell death

We next wanted to determine whether rGzmC-mediated death involves DNA damage, another hallmark of apoptosis. Flow-TUNEL quantifies terminal deoxynucleotidyl terminase (TdT)–catalyzed incorporation of fluorescein-labeled nucleotides into the free 3′-OH DNA ends at the single cell level. As shown in Figure 4A, nearly 50% of YAC1 cells treated with perforin plus rGzmC were TUNEL positive after 5 minutes, increasing to 75% at 60 minutes. rGzmB and C both induced rapid TUNEL positivity with equal efficiency, but rGzmB-treated cells were slightly more TUNEL positive at 30 and 60 minutes. Minimal TdT labeling occurred in cells exposed to perforin or granzymes only.

GzmC induces single-strand DNA nicking.

(A) Flow-TUNEL analysis was performed on YAC1 cells treated with perforin plus 1 μM rGzmB (○) or rGzmC (▿) for the times specified. Untreated YAC1 cells (■) and cells incubated with perforin (▵), rGzmB (∗), or rGzmC (⋄) alone were also analyzed for FITC-TUNEL positivity. (B) YAC1 target cells were untreated or treated with perforin, rGzmB, rGzmC, perforin plus rGzmB, or perforin plus rGzmC (1 μM). Genomic DNA was harvested after incubation at 37°C for 1 or 2 hours and was visualized on an ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel. To estimate cell viability in the same experiment, the percentage of 7-AADlo target cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (values for each sample are shown below each line). (C) Genomic DNA from YAC1 target cells treated as in panel B were radiolabeled with 32P-dATP by the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. DNA fragments were separated with denaturing alkaline gel electrophoresis and autoradiographed.

GzmC induces single-strand DNA nicking.

(A) Flow-TUNEL analysis was performed on YAC1 cells treated with perforin plus 1 μM rGzmB (○) or rGzmC (▿) for the times specified. Untreated YAC1 cells (■) and cells incubated with perforin (▵), rGzmB (∗), or rGzmC (⋄) alone were also analyzed for FITC-TUNEL positivity. (B) YAC1 target cells were untreated or treated with perforin, rGzmB, rGzmC, perforin plus rGzmB, or perforin plus rGzmC (1 μM). Genomic DNA was harvested after incubation at 37°C for 1 or 2 hours and was visualized on an ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel. To estimate cell viability in the same experiment, the percentage of 7-AADlo target cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (values for each sample are shown below each line). (C) Genomic DNA from YAC1 target cells treated as in panel B were radiolabeled with 32P-dATP by the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. DNA fragments were separated with denaturing alkaline gel electrophoresis and autoradiographed.

To assess whether rGzmC-induced DNA nicking was associated with oligonucleosomal fragmentation, we next evaluated target cell genomic DNA on agarose gels. Oligonucleosomal DNA laddering was induced by perforin plus rGzm B (Figure 4B) but failed to occur in target cells treated with perforin plus rGzmC for 1 or 2 hours. The same samples were analyzed by flow cytometry to ensure that cellular death had occurred: few 7-AADlo target cells persisted following treatment with perforin and either rGzm B or C, as expected (Figure 4B; percentages of 7-AADlo cells shown below each lane/treatment condition). These data suggested that GzmC-induced death is associated with single-stranded DNA nicking, not double-stranded cleavage. Nicked DNA can be radiolabeled with 32P-dATP using the Klenow polymerase; single-stranded nicked fragments can then be resolved with denaturing alkaline gel electrophoresis and autoradiography, as shown in Figure 4C. Extensive DNA nicking was revealed in cells treated with perforin plus rGzmC. The double-strand DNA breaks created by GzmB-activated CAD were also labeled, as predicted. DNA extracted from untreated cells, or cells treated with perforin or granzymes only, was not extensively nicked (Figure4C).

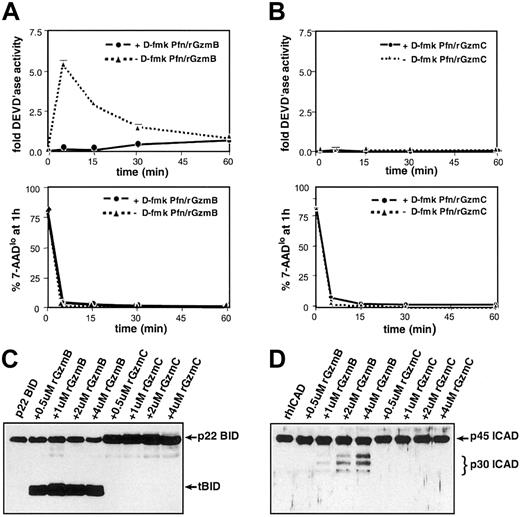

GzmC causes cell death without activating caspases, BID, or ICAD

Freshly prepared protein extracts derived from YAC1 cells treated with perforin plus rGzmB transiently generated significant DEVD'ase activity (measuring caspases-2, -3, and -7) (Figure 5A, top panel). High concentrations (greater than 25 μM) of D-fmk, a broad-spectrum fluoromethylketone-conjugated peptide inhibitor, completely inhibit caspase activity induced by rGzmB.9 When target cells were pretreated with 100 μM D-fmk, GzmB-induced DEVD'ase activity was not detected (Figure 5A, top panel). At every time point, samples were removed for 7-AAD–based cytometric analyses to estimate the target cell viability. GzmB caused a rapid reduction in the percentage of viable (ie, 7-AADlo) target cells regardless of caspase inhibition (Figure 5A, lower panel). In contrast, there was no measurable DEVD'ase activity produced in cells treated with perforin plus rGzmC (Figure 4B, top panel). Similarly, perforin plus rGzmC caused a rapid reduction in cell viability regardless of whether cells were pretreated with D-fmk (Figure B, lower panel). Beyond 60 minutes, advanced target cell destruction makes analysis of caspase activity impossible.

GzmC does not cleave or activate GzmB substrates.

(A) GzmB-induced caspase-3 activity in target cells. (top panel) YAC1 cells were pretreated with a fixed dose (100 μM) of the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor D-fmk or the DMSO vehicle for 30 minutes at 37°C. Next, the cells were treated with perforin plus 1 μM rGzmB and incubated at 37°C for 5, 15, 30, or 60 minutes. Cellular lysates were prepared, and DEVD-AMC cleavage was measured in triplicate using a spectrofluorometer. (bottom panel) Before target cell harvest at every time point, a fraction of each sample was stained with 7-AAD and quantified using flow cytometry to assess viability. (B) Absence of GzmC-induced caspase-3 activity. (top panel) As described in panel A, D-fmk– or DMSO-pretreated YAC1 cells were treated with perforin plus 1 μM rGzmC followed by fluorometric analysis. (bottom panel) Portions of the rGzmC-loaded samples were stained with 7-AAD and quantified with flow cytometry. (C) Full-length recombinant p22 BID was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes alone or with increasing concentrations of active rGzmB or rGzmC. Samples were harvested and electrophoresed on reducing SDS-PAGE gels. Western blot analysis was performed with a rabbit polyclonal anti-BID antibody. Only rGzmB directly processes p22 BID to the truncated BID (tBID) form. (D) rhICAD was processed as above in panel A and immunoblotted using a rabbit polyclonal anti-ICAD antibody. Only rGzmB processes ICAD to its p30 form.

GzmC does not cleave or activate GzmB substrates.

(A) GzmB-induced caspase-3 activity in target cells. (top panel) YAC1 cells were pretreated with a fixed dose (100 μM) of the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor D-fmk or the DMSO vehicle for 30 minutes at 37°C. Next, the cells were treated with perforin plus 1 μM rGzmB and incubated at 37°C for 5, 15, 30, or 60 minutes. Cellular lysates were prepared, and DEVD-AMC cleavage was measured in triplicate using a spectrofluorometer. (bottom panel) Before target cell harvest at every time point, a fraction of each sample was stained with 7-AAD and quantified using flow cytometry to assess viability. (B) Absence of GzmC-induced caspase-3 activity. (top panel) As described in panel A, D-fmk– or DMSO-pretreated YAC1 cells were treated with perforin plus 1 μM rGzmC followed by fluorometric analysis. (bottom panel) Portions of the rGzmC-loaded samples were stained with 7-AAD and quantified with flow cytometry. (C) Full-length recombinant p22 BID was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes alone or with increasing concentrations of active rGzmB or rGzmC. Samples were harvested and electrophoresed on reducing SDS-PAGE gels. Western blot analysis was performed with a rabbit polyclonal anti-BID antibody. Only rGzmB directly processes p22 BID to the truncated BID (tBID) form. (D) rhICAD was processed as above in panel A and immunoblotted using a rabbit polyclonal anti-ICAD antibody. Only rGzmB processes ICAD to its p30 form.

rGzmB efficiently cleaves p22 BID to p15 tBID, a key effector of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.11-14 16 rGzmC does not cleave recombinant p22 BID under the same conditions (Figure 5C). rGzmB directly processes the 45-kDa recombinant human ICAD (rhICAD) into its p30 form, but rhICAD was not cleaved with rGzmC under similar conditions (Figure 5D). Western blot analyses of proteins extracted from YAC1 cells treated with perforin and rGzm B or C verified that rGzmB rapidly processes caspase-3, BID, and ICAD, but that rGzmC does not (data not shown).

GzmC causes mitochondrial changes in intact cells undergoing apoptosis

The mitochondria of untreated cells were in a classical condensed state, with narrow cristae separated by an electron-dense matrix space, identical to the mitochondria of cells treated with perforin only or granzymes only (data not shown). Perforin plus rGzmB caused extensive cristae reorganization, resembling the early morphologic changes that occur after the induction of apoptosis with other mediators in vitro and in situ (Figure6A).36 Perforin plus rGzmC induced profound swelling of YAC1 mitochondria with cavitation and loss of cristae structure and outer membrane (OM) rupture.

GzmC induces target cell mitochondrial depolarization, swelling, and cyt

c release in intact cells. (A) High-magnification transmission electron microscopy (× 22 000). The arrows point to the mitochondria of YAC1 cells treated as described in Figure 2C (bar represents 0.4 μm). The mitochondria of untreated YAC1 cells or of cells incubated with granzymes alone has the same appearance as perforin-treated mitochondria (data not shown). (B) Representative pseudocolor-coded images of TMRM fluorescence intensity in murine embryonic fibroblasts at the beginning (left panels) and at the end of the acquisition sequence (right panels). Cells were treated with perforin alone or with perforin plus 4 μM GzmC. Where indicated, cells were preincubated with 2 μM CsA for 30 minutes. Bar represents 7 μm. (C) Quantitation of the TMRM fluorescence changes over mitochondrial regions. Where indicated by the arrows, perforin and 4 μM rGzmC, and then 2 μM FCCP (to induce complete depolarization), were added. Fluorescence intensity changes were quantified as described in “Experimental procedures.” (D) Immunofluorescence for cytc in YAC1 cells. YAC1 target cells were treated with perforin alone (i-ii), perforin plus 1 μM rGzmB (iii-iv), or perforin plus 1 μM rGzmC (v-vi) for 30 minutes and were immunostained for cytc (red). Duplicate images in the lower panels (ii,iv,vi) show nuclear staining by DAPI (blue). Note that target cells treated with perforin plus granzymes display diminished cyt cstaining and have apoptotic condensed nuclei. Untreated target cells and cells treated with granzymes alone resembled those treated with perforin only (i,ii, and data not shown).

GzmC induces target cell mitochondrial depolarization, swelling, and cyt

c release in intact cells. (A) High-magnification transmission electron microscopy (× 22 000). The arrows point to the mitochondria of YAC1 cells treated as described in Figure 2C (bar represents 0.4 μm). The mitochondria of untreated YAC1 cells or of cells incubated with granzymes alone has the same appearance as perforin-treated mitochondria (data not shown). (B) Representative pseudocolor-coded images of TMRM fluorescence intensity in murine embryonic fibroblasts at the beginning (left panels) and at the end of the acquisition sequence (right panels). Cells were treated with perforin alone or with perforin plus 4 μM GzmC. Where indicated, cells were preincubated with 2 μM CsA for 30 minutes. Bar represents 7 μm. (C) Quantitation of the TMRM fluorescence changes over mitochondrial regions. Where indicated by the arrows, perforin and 4 μM rGzmC, and then 2 μM FCCP (to induce complete depolarization), were added. Fluorescence intensity changes were quantified as described in “Experimental procedures.” (D) Immunofluorescence for cytc in YAC1 cells. YAC1 target cells were treated with perforin alone (i-ii), perforin plus 1 μM rGzmB (iii-iv), or perforin plus 1 μM rGzmC (v-vi) for 30 minutes and were immunostained for cytc (red). Duplicate images in the lower panels (ii,iv,vi) show nuclear staining by DAPI (blue). Note that target cells treated with perforin plus granzymes display diminished cyt cstaining and have apoptotic condensed nuclei. Untreated target cells and cells treated with granzymes alone resembled those treated with perforin only (i,ii, and data not shown).

The appearance of these striking morphologic changes prompted us to investigate mitochondrial function during GzmC-mediated apoptosis. We assessed mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) changes with real-time imaging using the potentiometric dye tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM). Treatment of MEFs with perforin plus rGzmC induced mitochondrial depolarization, whereas perforin alone had no effect (Figure 6B). The permeability transition pore (PTP) can mediate mitochondrial swelling and depolarization during the course of apoptosis.37 We therefore investigated whether the PTP inhibitor cyclosporin A (CsA) was capable of inhibiting the loss of Δψm induced by rGzmC. The TMRM fluorescence decrease (ie, depolarization) was not inhibited by CsA (Figure 6B). Quantitation of the TMRM fluorescence changes over mitochondrial regions showed that rGzmC caused a marked CsA-insensitive depolarization, approximately 10% to 15% greater than the depolarization induced by rGzmB in a similar experiment.16

Finally, we determined that these mitochondrial changes were ultimately followed by cyt c release during the late stages of GzmC-induced death. YAC1 cells were treated with perforin plus rGzmB or C for 30 minutes and then stained for cyt c and nuclear morphology (Figure 6D). Perforin plus rGzmC triggered cyt crelease from mitochondrial stores (Figure 6Diii vs 3), whereas cytc remained in the mitochondria of cells exposed to perforin alone (Figure 6Di). After release, the intensity of cyt cstaining is dimmer, probably because cyt c diffuses broadly into the cytoplasm.16

GzmC directly induces swelling and membrane depolarization in isolated mitochondria

Isolated mitochondria primed with a high concentration of Ca2+ (400 μM) undergo a sudden increase of inner mitochondrial membrane permeability because of opening of the PTP. A low concentration of Ca2+ does not cause swelling per se (monitored by side scatter at 545 nm; Figure7A). When rGzmC was added, the side scatter changes indicated that substantial swelling developed within 2 minutes. “High” doses of rGzmC are required to induce these changes because very large amounts of mitochondrial protein are treated with very small amounts of rGzmC (4 pmol rGzmC/1 mg mitochondria); these results cannot be directly compared with the concentrations of rGzmC used to induce cell death. Pretreatment with the PTP inhibitors CsA or adenosine diphosphate (ADP) plus oligomycin (not shown) did not affect rGzmC-induced swelling. In an identical experiment, the attenuated rGzmCSer184Ala mutant did not cause detectable swelling (data not shown). Of note, rGzmB did not directly induce measurable mitochondrial swelling in a similar experiment,16 further distinguishing the mitochondrial effects of these 2 enzymes.

GzmC directly causes mitochondrial swelling and depolarization in isolated mitochondria.

(A-B) Mitochondrial volume and membrane potential changes of purified murine liver mitochondria (MLM, 0.5 mg/mL) were monitored as described.16 In both panels, where indicated by the arrows, 40 μM Ca2+ and 4 μM rGzmC (black and gray traces) were added. Where noted (gray trace), 1 μM CsA was present from the beginning. In panel A, 400 μM Ca2+ (light gray trace) was added where indicated to induce complete swelling. In all the experiments depicted in panel B, complete depolarization was achieved by adding 400 nM FCCP where indicated. (C) Dose dependence of GzmC-induced mitochondrial swelling. The experiment was performed as in panel A, except that the indicated concentrations of rGzmC were added. (D) Ca2+ dependence of GzmC-induced swelling. The experiment was carried out as in panel A, except that the indicated Ca2+ concentrations were added before 4 μM rGzmC. Ca2+ concentrations of 50 μM or less did not cause detectable mitochondrial swelling. (E) Differential release of fluorescent dyes entrapped in the mitochondrial matrix by GzmC. Mitochondria loaded with 10 μM rhod-2-am or calcein-am were left untreated or were treated with 200 μM Ca2+ in the presence of 1 μM CsA, 2 μM mastoparan, or 4 μM rGzmC. After 30 minutes, mitochondria were pelleted, and calcein and rhod-2 fluorescence levels were measured in the pellet and in the supernatant. Data are normalized for the untreated mitochondria.

GzmC directly causes mitochondrial swelling and depolarization in isolated mitochondria.

(A-B) Mitochondrial volume and membrane potential changes of purified murine liver mitochondria (MLM, 0.5 mg/mL) were monitored as described.16 In both panels, where indicated by the arrows, 40 μM Ca2+ and 4 μM rGzmC (black and gray traces) were added. Where noted (gray trace), 1 μM CsA was present from the beginning. In panel A, 400 μM Ca2+ (light gray trace) was added where indicated to induce complete swelling. In all the experiments depicted in panel B, complete depolarization was achieved by adding 400 nM FCCP where indicated. (C) Dose dependence of GzmC-induced mitochondrial swelling. The experiment was performed as in panel A, except that the indicated concentrations of rGzmC were added. (D) Ca2+ dependence of GzmC-induced swelling. The experiment was carried out as in panel A, except that the indicated Ca2+ concentrations were added before 4 μM rGzmC. Ca2+ concentrations of 50 μM or less did not cause detectable mitochondrial swelling. (E) Differential release of fluorescent dyes entrapped in the mitochondrial matrix by GzmC. Mitochondria loaded with 10 μM rhod-2-am or calcein-am were left untreated or were treated with 200 μM Ca2+ in the presence of 1 μM CsA, 2 μM mastoparan, or 4 μM rGzmC. After 30 minutes, mitochondria were pelleted, and calcein and rhod-2 fluorescence levels were measured in the pellet and in the supernatant. Data are normalized for the untreated mitochondria.

We next assessed whether swelling was associated with mitochondrial depolarization. When mitochondria were added to buffer containing the potentiometric dye rhodamine 123, fluorescence dropped as the dye was accumulated in the matrix of polarized mitochondria (Figure 7B). Addition of 40 μM Ca2+ resulted in the expected transient depolarization because of the use of Δψm to take up Ca2+. The subsequent addition of rGzmC caused a CsA-insensitive fluorescence increase (ie, depolarization) that approached the maximum level attained with the protonophore FCCP (carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenyl hydrazone) (Figure 7B). As expected, the swelling of mitochondria incubated in saline buffers caused the release of cyt c from outer membrane rupture, which occurred 15 minutes after the rupture caused by treatment with GzmC alone (not shown).

We next investigated the dose and Ca2+ dependence of rGzmC-induced mitochondrial swelling. rGzmC caused CsA-insensitive mitochondrial swelling in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 6C). Because Ca2+ concentrations of 50 μM and less do not cause swelling per se (not shown), the Ca2+ dependence of GzmC-induced swelling can be studied by priming mitochondria with increasing Ca2+ concentrations and measuring the swelling induced by a fixed dose of rGzmC. GzmC-mediated swelling is Ca2+ dependent, reaching a maximum at a Ca2+concentration of 30 μM (Figure 7D).

Opening of the PTP is favored by mitochondrial Ca2+accumulation. In this regard, the Ca2+ dependence of GzmC-induced swelling resembled a characteristic feature of the PTP. However, the mitochondrial effects of GzmC were not blocked by PTP inhibitors (eg, CsA). We therefore decided to compare the size-exclusion properties of the mitochondrial pore(s) generated by GzmC with the properties of the PTP, induced either by high-dose Ca2+ or by the CsA-insensitive inducer mastoparan.38 Two fluorophores of different molecular weights, calcein (approximately 620 Da) and rhod-2 (approximately 860 Da), were loaded into the mitochondrial matrix. Openings of the inner mitochondrial membrane of exclusion sizes larger than the dye causes their release from the mitochondrial matrix. Opening of the PTP (which has an exclusion size of approximately 1500 Da) by 400 μM Ca2+ consistently induced a CsA-sensitive release of both dyes. Mastoparan also caused the release of calcein and rhod-2 from the mitochondrial matrix. However, rGzmC induced only the release of calcein, whereas rhod-2 was selectively retained in the mitochondrial matrix (Figure 7E). These data suggest that the pore opened by rGzmC differs from the classical PTP in its size-exclusion properties because it only allows the flux of solutes of smaller molecular weight.

Discussion

In this report, we describe the ability of murine GzmC to cause cell death. The induction of death requires its protease activity and is characterized by the rapid externalization of phosphatidylserine, nuclear condensation, and single-stranded DNA nicking. The kinetics of these events are similar to those caused by GzmB. The induction of death did not involve the production of activated caspases, the cleavage of BID, or the activation of the CAD nuclease. However, GzmC did cause rapid mitochondrial swelling and depolarization in intact cells or in isolated mitochondria, and this mitochondrial damage was not prevented by cyclosporin A pretreatment. These results suggest that GzmC rapidly induces target cell death by attacking nuclear and mitochondrial targets and that these targets are distinct from those used by GzmB to cause classical apoptosis.

The death induced by GzmC occurs rapidly, with kinetics similar to those observed for GzmB, and the potency of this enzyme (on a molar basis) is similar to that of GzmB. The induction of cell death by GzmB and C is not a generic property of all neutral serine proteases because 3 highly related neutrophil azurophil granule enzymes (neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase 3) all failed to induce cell death in this in vitro system. The characteristics of the cell death induced by GzmC have many of the hallmarks of apoptosis, but the death induced by GzmC is distinct from that of GzmB in several ways. First, nuclear condensation is not always associated with nuclear fragmentation. Second, the DNA damage appears to be single-stranded nicking, not oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation characteristic of CAD activation. Third, even though GzmC-induced death is associated with late cyt c release from damaged mitochondria, there is no evidence for caspase-3 activation during the early stages of apoptosis. Fourth, GzmB does not directly damage isolated mitochondria, but GzmC causes isolated mitochondria to rapidly depolarize and swell. All these differences strongly suggest that these 2 proteases induce cell death by attacking a different set of substrates.

The DNA damage caused by GzmC does not appear to involve the activation of CAD because oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation does not occur. This finding also makes it unlikely that GzmC causes DNA damage by releasing endonuclease G (EndoG) from mitochondria given that EndoG also causes oligonucleosomal DNA degradation.39 Instead, GzmC rapidly induces single-stranded DNA nicks in target cells. At least 2 different nucleases could potentially account for this finding. GzmA induces single-stranded DNA nicking by cleaving and activating a single-stranded DNase within the SET complex.19Alternatively, mitochondria contain a caspase-independent nuclease known as apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) that can be released from mitochondria during the induction of cell death.40 AIF causes a unique form of nuclear condensation that is similar to that observed for GzmC, and it causes long-range DNA nicking but not oligonucleosomal DNA laddering.41 For these reasons, it is possible that the mitochondrial release of AIF or the activation of the SET-associated DNase (or additional nucleases not yet described) may play roles in the nuclear changes observed with GzmC-induced death. Additional experimentation will be required to identify the responsible nucleases.

GzmC can rapidly induce mitochondrial swelling and depolarization in intact cells or on isolated mitochondrial preparations. Although GzmB can cause rapid mitochondrial depolarization in intact cells, it has no effect on isolated mitochondria, suggesting that it requires a cellular cofactor to cause mitochondrial damage.16 GzmC-induced swelling was amplified by small Ca2+ prepulses, reminiscent of the Ca2+ dependence of the PTP; however, PTP inhibitors did not block this swelling. This fact cannot be used to rule out a role for PTP because other inducers can operate in a Ca2+-dependent (but CsA-insensitive) fashion.38,42 Patch-clamp experiments revealed that the open conformation of the PTP displays a 1.8-nanoSiemens (nS) full conductance and a typical 0.9-nS subconductance state.43The 1.8-nS conductance corresponds to a pore exclusion size of approximately 1500 Da, whereas the 0.9-nS conductance is predicted to correspond to a cutoff of approximately 750 Da. Opening of the PTP in a subconductance mode permeant to Ca2+, but not to sucrose, has been reported in isolated mitochondria and intact cells.44 GzmC characteristics might reflect a selective opening of the PTP in a subconductance mode. The estimated pore size induced by GzmC, based on calcein flux (approximately 620 Da), is compatible with the PTP operating in its half-conductance mode. On the other hand, all PTP conductances disappear in the presence of CsA.43 44 It is therefore conceivable that the GzmC-induced inner mitochondrial (IM) pore has novel features that will become clearer with a subsequent full characterization. The late release of cyt c from GzmC-treated cells may be a consequence of direct damage to the inner mitochondrial membrane caused by GzmC, followed by rupture of the outer membrane with attendant release of all mitochondrial contents. Regardless, cyt crelease was not associated with the rapid activation of caspase-3 or with the activation of CAD. The dramatic drop in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels that occurs after treatment with perforin and rGzmC (data not shown) correlated with the sudden mitochondrial depolarization observed in situ; this change may also limit the ability of caspase to be activated.

A functional role of GzmC for cytotoxic lymphocyte-mediated target cell death has not yet been established. However, the GzmB knockout mouse produced in our laboratory several years ago displays dramatically reduced expressed of Gzms C, D, and F in the LAK cell compartment, presumably because of a so-called neighborhood effect from the retained PGK-neo cassette in the GzmB gene.23 We have recently removed the PGK-neo cassette from the GzmB gene using LoxP-Cre–mediated recombination and have created mice that are deficient for GzmB only (D. Thomas, R. Behl, and T.J.L., unpublished, 2001). Comparisons of the cytotoxic repertoires of the lymphocytes derived from these mice are in progress. However, preliminary experiments in an established graft-versus-host disease model strongly suggest that the mitigation of graft-versus-host disease previously observed with GzmB cluster-deficient lymphocytes45 may be attributed in part to the reduced expression of the orphan granzymes downstream from GzmB. These results support the idea that some of the orphan granzymes (perhaps including GzmC) are expressed in T cells that are activated in vivo and that they contribute significantly to the tissue damage associated with graft-versus-host disease. These results create a strong biologic foundation for the continued study of the orphan granzymes in the GzmB gene cluster.

The diversity of protease specificities of the granzymes is almost certainly a fail-safe mechanism for CTL to kill target cells that express inhibitors of GzmB. Virus-infected cells46,47and tumor cells48,49 are known to express serpin inhibitors of GzmB, and adenovirus expresses a decoy substrate for GzmB that is an efficient inhibitor.50 When these GzmB-specific inhibitors are present, granzymes with different specificities (such as A or C) may still be able to induce target cell death by activating alternative death pathways. This adaptation may be critical for survival of the host.

The results presented in this study clearly establish GzmC as an enzyme that can cause cell death. The specificity of this enzyme and its target cell substrates are unknown, but a strong rationale for the continued study of this enzyme is provided by the results described here. The unique pattern of nuclear and mitochondrial damage induced by this enzyme suggests that it will prove to be an important tool for understanding an alternative apoptotic pathway. The physiologic relevance of this pathway is suggested by the GzmB cluster knockout model, but proof of its importance awaits the development and description of the GzmC loss-of-function mouse.

We thank Mia Sorcinelli for skillful technical assistance and Nancy Reidelberger for expert editorial assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 19, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2485.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK49786 (T.J.L.) and CA50239 (S.J.K.). L.S. is a Human Frontier Science Program Long Term Fellow.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Note added in proof

Bailey and Kelly51 first showed that a T-cell clone that expressed granzymes B and C exhibited less cytotoxicity when its granzyme C expression was inhibited by an antisense approach.

Author notes

Timothy J. Ley, Division of Oncology, Washington University, Campus Box 8007, 660 South Euclid Ave, St Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: tley@im.wustl.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal