The recently published crystal structure of the external domains of αVβ3 confirms the prediction that the aminoterminal portion of αV, which shares 40% homology with αIIb, folds into a β-propeller structure and that the 4 calcium-binding domains are positioned on the bottom of the propeller. To gain insight into the role of the calcium-binding domains in αIIb biogenesis, we characterized mutations in the second and third calcium-binding domains of αIIb in 2 patients with Glanzmann thrombasthenia. One patient inherited a Val298Phe mutation in the second domain, and the other patient inherited an Ile374Thr mutation in the third domain. Mammalian cell expression studies were performed with normal and mutant αIIb and β3 cDNA constructs. By flow cytometry, expression of αIIb Val298Phe/β3 in transfected cells was 28% of control, and expression of αIIbIle374Thr/β3 was 11% of control. Pulse-chase analyses showed that both mutant pro-αIIb subunits are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and degraded. Mutagenesis studies of the Val298 and Ile374 residues showed that these highly conserved, branch-chained hydrophobic residues are essential at these positions and that biogenesis and expression of αIIbβ3 is dramatically affected by structural variations in these regions of the calcium-binding domains. Energy calculations derived from a new model of the αIIb β-propeller indicate that these mutations interfere with calcium binding. These data suggest that the αIIb calcium-binding domains play a key structural role in the β-propeller, and that the structural integrity of the calcium-binding domains is critical for integrin biogenesis.

Introduction

The platelet glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa (integrin αIIbβ3) receptor plays a key role in platelet aggregation. Inherited abnormalities of αIIbβ3 result in Glanzmann thrombasthenia, a variably severe mucocutaneous bleeding disorder.1,2 Conversely, inhibition of αIIbβ3 with antagonist drugs can prevent the thrombotic complications of percutaneous coronary interventions and acute coronary syndromes.3

Mutations in either αIIb or β3 can result in Glanzmann thrombasthenia because the subunits must form a calcium-dependent complex for normal biogenesis and surface expression.4-6The αIIb subunit contains 4 calcium-binding domains, and mutations within or adjacent to the first and fourth domains, as well as between the second and third domains, have been reported to disrupt αIIbβ3 biogenesis by preventing receptor transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi.7-11

The recent publication of the crystal structure of the external domains of αVβ3 confirmed the prediction of Springer, based on computer modeling, that the amino terminus of αV folds into a 7-bladed β-propeller.12,13 The 40% sequence homology between αIIb and αV makes it likely that these integrin α-subunit siblings share the same basic structural elements. Each blade is composed of 4 β strands, which are connected by loops extending either above or below the plane of the propeller. The 4 calcium-binding domains are located in loops extending below propeller blades 4 to 7. The calcium-binding domains were originally described as being similar to EF hand structures, but more recent data from computer modeling and the crystallographic structure of αVβ3 indicate that the domains are β-hairpin loops.12-15 This has structural significance in that β-hairpin turns can play an important role in the initial folding of complex β structures.16

In the present study, we describe data on 2 patients with Glanzmann thrombasthenia. One has a mutation in the second calcium-binding domain of αIIb, and the other has a mutation in the third calcium-binding domain. Both of these mutations (Val298Phe and Ile374Thr) are shown to be at key structural residues within the calcium-binding domains, and both interfere with αIIbβ3 biogenesis, thus potentially linking these phenomena. In fact, molecular modeling simulations indicate that both mutations interfere with calcium coordination and thus suggest that structurally intact calcium-binding domains are essential for αIIbβ3 biogenesis, heterodimer stability, and surface expression.

Patients, materials, and methods

Case reports

Patient M was diagnosed as having Glanzmann thrombasthenia at 1 year of age based on typical laboratory findings and clinical history.17 Neither of his parents had any bleeding symptoms and there was no family history of bleeding. His parents originated from Puerto Rico and Canada, and there was no known consanguinity. Patient C was diagnosed as having Glanzmann thrombasthenia at 8 years of age based on typical laboratory findings and clinical history. His family history is significant for his father and his 2 siblings having bleeding symptoms, whereas his mother is asymptomatic. His paternal aunt and her child also had bleeding symptoms. The mother's family originated from Sicily and the father's from Naples. There was no known consanguinity. Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Cornell Medical Center, and University of Massachusetts Medical School; informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Surface expression of platelet glycoprotein (GP) Ib, αIIbβ3, and αVβ3 receptors

Platelet preparation and quantitative assessment of surface receptors by radiolabeled antibody binding was performed as previously described.18 Platelet surface GPIb was assessed by the binding of the murine monoclonal antibody (mAb) 6D119; αIIbβ3 was assessed by the binding of the complex-dependent murine mAb 10E520 and the Fab fragment of the mouse/human chimeric mAb 7E321,22 (which also reacts with αVβ3); and αVβ3 was assessed by the binding of the murine mAb LM60923 (provided by Dr D. Cheresh, Scripps Institute, La Jolla, CA).

Immunoblot analyses

Lysates of platelets and transfected cells were prepared as previously described.18,24,25 Immunoblot analyses of solubilized platelet and transfected cell proteins were performed by separating the proteins by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then electrotransferring them onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA), as previously described.18,24 The membranes were then incubated with a murine mAb specific for the heavy chain of mature αIIb, PMI-126,27 (provided by Dr M. Ginsberg, Scripps Institute), or a murine mAb specific for β3, 7H2.28Secondary labeling was performed using either a gold-conjugated antimouse IgG antibody with enhancement of the gold stain using a silver reagent (AuroProbe Forte kit, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ), or using a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated rabbit antimouse κ light chain–specific antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA).

DNA sequence analysis

gDNA was isolated from whole blood using the Puregene system (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN), per the manufacturer's instructions. Oligonucleotide primers (Operon Technologies, Alameda, CA) were designed for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of one or more exons; one primer of each set was biotinylated for the purification of ssDNA for sequence analysis. The primers used for PCR and sequence analyses of αIIb are listed in Tables1 and 2. PCR amplification of the exons encoding αIIb was performed by adding about 100 ng gDNA, 0.2 μM biotinylated primer, 0.6 μM nonbiotinylated primer, 0.2 mM deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (AmpliTaq; PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane]-HCl, pH 8.3, in a total volume of 50 μL. Reaction tubes were preheated to 96°C for 5 minutes, followed by successive rounds of 94°C for 45 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds for 30 cycles, with a final extension time of 10 minutes at 72°C. The ssDNA was isolated for direct sequence analysis using a magnetic bead purification system (Dynal, Lake Success, NY). Sequencing was performed using Sequenase Version 2.0 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The reaction products were electrophoresed in an 8% denaturing acrylamide gel and exposed to film.

Primers for PCR amplification of αIIb29

| Exon . | Name* . | Antisense primer 5′→3′† . | Name . | Sense primer 5′→3′ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | B1A | XTGCTGCTCTCTCCCAATACCCCAAC | 1S | CCTGTGGAGGAATCTGAA |

| 2 + 3 | B3A | XAGACTTGGGCTCCTCCTGGCCCCAG | 2SII | ACGGTGGTCTGTGAGGTGTCATTG |

| 4 | B4A | XCAAGCCGTCGCGAGTGGG | 4S | CAATCGGGGGCAGGGACAC |

| 5 + 6 | 6A | GAAAATATCCGCAACTGGAG | B5S | XTCCCTTCACCCCTGGGCTGACCCCT |

| 7 | B9A | XTTGTCAGCCTGAGAACTGGGATAAG | 7SII | TTCTGGCGGCTATTATTTCTTAGG |

| 8 + 9 | B9A | XTTGTCAGCCTGAGAACTGGGATAAG | 8/9SII | CTCCGTTTTTCCATCTGCACAATG |

| 10 + 11 | 10/11AII | GAGGGGCAGCTCTGGTAATTTG | B10S | XTCACCTGGAGTGGGAGGTTGCTTTG |

| 12 | 12S2 | GAGAGCAAGGGTCGAGGAGAT | B12A | XCTGTTAACCCCTCTGCAGCAAGTAG |

| 13 | B13A | XCTTGGCACTTCCAGCGAATGTCCAA | 13SII | CACTTTGCACCCCTTTCCTA |

| 14 + 15 | B15A | XCTGAGGTCCCAGATCCTTTAAGGCC | 14S2 | CTGGGAAGATGAGATGAGGA |

| 16 | B17A | XCTCCCAGCCCTGCCAATCCCCTGCC | 16SII | GTGTCCTACCTCAGACCAAG |

| 17 | B17A | XCTCCCAGCCCTGCCAATCCCCTGCC | 17SII | CTCAGAAGCTATGTGAGTGGC |

| 18 | B18A | XTACATTGTGACTTGGCACTAACCCT | 18S | CAGGTGCCTACTGGCCAG |

| 19 + 20 | B20A | XAGCCAAGGCTCCAGTGCCTCCCAGG | 19S | CAAGCCCACTGTTTTCCT |

| 21 | 21A | AGAACTATGTGGCTCTAA | B21S | XCAGACCTTCCAAGGGAGCTTAAATA |

| 22 | B22A | XCCTGGCCTCGAAAGACCCTTCTGTA | 22S | AGGCCACATTCAGGGCAG |

| 23 + 24 | B24AII | XAAGGTGGATGCTGAGGTGAAGACCA | 23SII | CCTAGAGGAAGTTCTTTCCCAGGTC |

| 25 | B26AII | XCAAGTGTCTTTCAGCTCACCCCAGA | 25S | GGTATTGGGGAGCCTCGC |

| 26 | B26AII | XCAAGTGTCTTTCAGCTCACCCCAGA | 26SII | CCTGTCAACCCTCTCAAGGTAAGAG |

| 27 | B27A | XCTCCCAGAGCAAAGTGGTCCCGGCC | 27S | CCTTCTGCGTTGGGTCCT |

| 28 | B28A | XCTTTTCTGGCTGGGCACTGACTGGG | 28SII | ATTAGGTCAGAGGCAGGGCTTC |

| 29 | 29AII | TGGTCCCTGGATTACCCACTTG | B29S | XTGTGAAAGGCAGGTGTCAAGGTGAC |

| 30 | B30A | XCAATGGAACAGCTCCAACCCAAAGC | 30S | CTGCGCTGGTCCAGGGAG |

| Exon . | Name* . | Antisense primer 5′→3′† . | Name . | Sense primer 5′→3′ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | B1A | XTGCTGCTCTCTCCCAATACCCCAAC | 1S | CCTGTGGAGGAATCTGAA |

| 2 + 3 | B3A | XAGACTTGGGCTCCTCCTGGCCCCAG | 2SII | ACGGTGGTCTGTGAGGTGTCATTG |

| 4 | B4A | XCAAGCCGTCGCGAGTGGG | 4S | CAATCGGGGGCAGGGACAC |

| 5 + 6 | 6A | GAAAATATCCGCAACTGGAG | B5S | XTCCCTTCACCCCTGGGCTGACCCCT |

| 7 | B9A | XTTGTCAGCCTGAGAACTGGGATAAG | 7SII | TTCTGGCGGCTATTATTTCTTAGG |

| 8 + 9 | B9A | XTTGTCAGCCTGAGAACTGGGATAAG | 8/9SII | CTCCGTTTTTCCATCTGCACAATG |

| 10 + 11 | 10/11AII | GAGGGGCAGCTCTGGTAATTTG | B10S | XTCACCTGGAGTGGGAGGTTGCTTTG |

| 12 | 12S2 | GAGAGCAAGGGTCGAGGAGAT | B12A | XCTGTTAACCCCTCTGCAGCAAGTAG |

| 13 | B13A | XCTTGGCACTTCCAGCGAATGTCCAA | 13SII | CACTTTGCACCCCTTTCCTA |

| 14 + 15 | B15A | XCTGAGGTCCCAGATCCTTTAAGGCC | 14S2 | CTGGGAAGATGAGATGAGGA |

| 16 | B17A | XCTCCCAGCCCTGCCAATCCCCTGCC | 16SII | GTGTCCTACCTCAGACCAAG |

| 17 | B17A | XCTCCCAGCCCTGCCAATCCCCTGCC | 17SII | CTCAGAAGCTATGTGAGTGGC |

| 18 | B18A | XTACATTGTGACTTGGCACTAACCCT | 18S | CAGGTGCCTACTGGCCAG |

| 19 + 20 | B20A | XAGCCAAGGCTCCAGTGCCTCCCAGG | 19S | CAAGCCCACTGTTTTCCT |

| 21 | 21A | AGAACTATGTGGCTCTAA | B21S | XCAGACCTTCCAAGGGAGCTTAAATA |

| 22 | B22A | XCCTGGCCTCGAAAGACCCTTCTGTA | 22S | AGGCCACATTCAGGGCAG |

| 23 + 24 | B24AII | XAAGGTGGATGCTGAGGTGAAGACCA | 23SII | CCTAGAGGAAGTTCTTTCCCAGGTC |

| 25 | B26AII | XCAAGTGTCTTTCAGCTCACCCCAGA | 25S | GGTATTGGGGAGCCTCGC |

| 26 | B26AII | XCAAGTGTCTTTCAGCTCACCCCAGA | 26SII | CCTGTCAACCCTCTCAAGGTAAGAG |

| 27 | B27A | XCTCCCAGAGCAAAGTGGTCCCGGCC | 27S | CCTTCTGCGTTGGGTCCT |

| 28 | B28A | XCTTTTCTGGCTGGGCACTGACTGGG | 28SII | ATTAGGTCAGAGGCAGGGCTTC |

| 29 | 29AII | TGGTCCCTGGATTACCCACTTG | B29S | XTGTGAAAGGCAGGTGTCAAGGTGAC |

| 30 | B30A | XCAATGGAACAGCTCCAACCCAAAGC | 30S | CTGCGCTGGTCCAGGGAG |

B indicates biotinylated.

X, biotin.

Primers for sequencing αIIb

| Exon . | Name . | Sequence primer 5′→3′ . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1S2 | GGGAAGGAGGAGGAGCTG |

| 2 + 3 | 2S | CTGGGATACGCTGGAATC |

| 3S | GGGCTTCAGCGCCCCAC | |

| 4 | 4S2 | GGCCAGGAGGAGCCCAAGTCT |

| 5 + 6 | 5A | CTGGAAGGGAAGTCCTGAGG |

| 5/6A | CAAAGCGGTCTCCTTCGG | |

| 7 | 7S | CGTGCCCATCCGTACACC |

| 8 + 9 | 8/9SII | CTCCGTTTTTCCATCTGCACAATG |

| 9S | CTGGAAAAGACTAATTTG | |

| 10 + 11 | 10A | TATTCTGAAGTCTCAGTTCC |

| 10/11A | CAACTGGGTAGGGGTGGG | |

| 12 | 12S | CCCTGGTCCAGTCCCATG |

| 12SII | TGTTCCTGCAGCCGCGAG | |

| 13 | 13S | CAATCAGCCACTTCCTTT |

| 14 + 15 | 14/15S | CCCCATACCCTAATCGCC |

| 15S | AGGCCAGGAGGAGCCACA | |

| 16 | 16S3 | GTGAGCTGGTGAGGAGGC |

| 17 | 17S | ACTCCCCCGGAGGCTGGCCAG |

| IIbL | CTAAATGCCGAGCTGCAGCTG | |

| 18 | 18S | CAGGTGCCTACTGGCCAG |

| 19 + 20 | 19S2 | GTAATCCCTAAACCTCACACA |

| 20SII | CTTTCTGCCTATCATACCTGC | |

| 21 | 21A2 | AATCTGGTTATTCATGAG |

| 22 | 22S2 | TCCTAAGTGGGGCACTTG |

| 23 + 24 | 23S3 | AAAGTCACTGGGCTGGTG |

| 24S2 | CTCACAGGCCAATCAGGG | |

| 25 | 25S3 | TGGCTGGGGTGAGCGGG |

| 26 | 26S | CCAACCACCGGGGCACCT |

| 27 | 27S3 | GGGTGGGGGATGATGGGGTG |

| 28 | 28S | CGGGTGTGGGACCTGGAC |

| 29 | 29A | AGGGCAGAGCCAAGCCTGTG |

| 30 | 30S2 | AGCATACTTCCTCACATGTGC |

| Exon . | Name . | Sequence primer 5′→3′ . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1S2 | GGGAAGGAGGAGGAGCTG |

| 2 + 3 | 2S | CTGGGATACGCTGGAATC |

| 3S | GGGCTTCAGCGCCCCAC | |

| 4 | 4S2 | GGCCAGGAGGAGCCCAAGTCT |

| 5 + 6 | 5A | CTGGAAGGGAAGTCCTGAGG |

| 5/6A | CAAAGCGGTCTCCTTCGG | |

| 7 | 7S | CGTGCCCATCCGTACACC |

| 8 + 9 | 8/9SII | CTCCGTTTTTCCATCTGCACAATG |

| 9S | CTGGAAAAGACTAATTTG | |

| 10 + 11 | 10A | TATTCTGAAGTCTCAGTTCC |

| 10/11A | CAACTGGGTAGGGGTGGG | |

| 12 | 12S | CCCTGGTCCAGTCCCATG |

| 12SII | TGTTCCTGCAGCCGCGAG | |

| 13 | 13S | CAATCAGCCACTTCCTTT |

| 14 + 15 | 14/15S | CCCCATACCCTAATCGCC |

| 15S | AGGCCAGGAGGAGCCACA | |

| 16 | 16S3 | GTGAGCTGGTGAGGAGGC |

| 17 | 17S | ACTCCCCCGGAGGCTGGCCAG |

| IIbL | CTAAATGCCGAGCTGCAGCTG | |

| 18 | 18S | CAGGTGCCTACTGGCCAG |

| 19 + 20 | 19S2 | GTAATCCCTAAACCTCACACA |

| 20SII | CTTTCTGCCTATCATACCTGC | |

| 21 | 21A2 | AATCTGGTTATTCATGAG |

| 22 | 22S2 | TCCTAAGTGGGGCACTTG |

| 23 + 24 | 23S3 | AAAGTCACTGGGCTGGTG |

| 24S2 | CTCACAGGCCAATCAGGG | |

| 25 | 25S3 | TGGCTGGGGTGAGCGGG |

| 26 | 26S | CCAACCACCGGGGCACCT |

| 27 | 27S3 | GGGTGGGGGATGATGGGGTG |

| 28 | 28S | CGGGTGTGGGACCTGGAC |

| 29 | 29A | AGGGCAGAGCCAAGCCTGTG |

| 30 | 30S2 | AGCATACTTCCTCACATGTGC |

Mutagenesis

Mutant αIIb cDNA constructs were generated using the splice by overlap extension PCR method as previously described.25The overlapping sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers used for the synthesis of the Val298Phe (985G>T) mutation were 5′CTGTCACTGACTTCAACGG3′ (sense) and 5′GTTGAAGTCAGTGACAGCC3′ (antisense) and the overlapping primers used for the Ile374Thr (1214T>C) mutation were 5′TGACACTGCAGTGGCTGC3′ (sense) and 5′CTGCAGTGTCATTGTAGCC3′ (antisense). The nucleotide substitutions are underlined. Control αIIb cDNA in the pcDNA3 mammalian cell expression vector (Invitrogen/Novex, Carlsbad, CA) was used as a template. The final PCR fragments carrying the mutations were ligated into the TA vector (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's instructions for sequence analysis to confirm the nucleotide substitution and identify any PCR artifacts. The TA vectors containing the PCR fragments were digested with Pml-1 and Cla-1 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) for ligation of the 600-bp fragments into control pcDNA3/αIIb vectors in which the same fragments were removed. Maxi-preparations (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) of the mutant αIIb/pcDNA3 cDNA constructs were performed for transfection and expression in mammalian cells.

Cell transfection and flow cytometry

Control and mutant αIIbβ3 receptors were expressed in human 293T cells. For transfection, cells were grown to 80% confluency in 100-mm tissue culture dishes. Control or mutant αIIb/pcDNA3 and β3/pcDNA3 cDNA constructs (6-8 μg each) were added with Lipofectamine according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). After 24 hours, cells from each dish were replated into 2 dishes. After 48 hours, cells (4 × 105/sample) were incubated with primary antibody for 30 minutes on ice followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled secondary antibody for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were washed, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) with LYSYS II software (Becton Dickinson). Background controls were cells incubated with secondary FITC-labeled antibody alone. Transfection efficiencies were monitored by determining the levels of β3 expressed as αVβ3 with the small amount of αV constitutively present in the 293T cells. In all experiments, the levels of αVβ3 expression were within 9% of control levels (means ± SDs of 3 experiments).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analyses

At 48 hours after transfection, cells were lysed in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), and protease inhibitors (0.025 μg/mL Pefabloc, 20 μM leupeptin, 10 μg/mL E64, 5 μg/mL pepstatin; Roche Molecular Biochemicals) for 30 minutes on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 10 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C and supernatants were precleared with protein A- or G-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) at 4°C for 30 minutes. Total protein was quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) detection method (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equivalent amounts of protein (400 μg) were incubated with the murine antihuman αIIb mAbs B1B530 31 (provided by Dr M. Poncz, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) and M-148 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 18 hours at 4°C. Protein G-Sepharose was added and incubated for 1.0 hours at 4°C. The Sepharose-antibody complexes were washed twice with lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl. The immunoprecipitates were released from the Sepharose beads by incubation in SDS sample buffer and electrophoresed under reducing conditions. The separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes and immunoblotted with the murine antihuman αIIb mAb PMI-1. Secondary labeling was with an HRP-conjugated rabbit antimouse κ light chain–specific antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) and membranes were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Pulse-chase analysis

The levels of αIIb and β3 subunits in 293T transfected cells (36 hours) were determined by immunoprecipitation of whole cell lysates using equivalent trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitable counts (about 1.5 × 106 counts/sample). Cells (5 × 105/60 mm tissue culture well; 2 wells/group) were incubated in methionine/cysteine-free medium for 30 minutes, labeled with 35S-methionine/cysteine-containing medium (300 μCi/well [11.1 MBq/well]) for 15 minutes, and chased with fresh medium containing unlabeled methionine and cysteine (1 mg/mL each). Cells were harvested at 0-, 2-, 4-, 8-, and 24-hour time points and immunoprecipitations were performed, as described (see “Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analyses”), using the αIIb-specific mAbs B1B530,31 and M-148 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and the β3-specific mAb AP332 (provided by Dr P. Newman, Blood Center S.E. Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI; 4 μg each mAb/sample). Samples (reduced) were subjected to SDS-PAGE (7.5% gel) and the dried gels were exposed to film.

Molecular modeling

The structure of the αIIb β-propeller was modeled using the coordinates from the crystal structure of αV obtained from the Brookhaven Protein Database, PDB entry 1JV2.13Sequences were aligned using the Homology module of InsightII (Accelrys, San Diego, CA). The αV and αIIb propeller regions (residues 1-439 and 1-451, respectively) share 68% sequence similarity. The regions of highest homology are the calcium-binding domains and the novel “cage” motif residues immediately preceding them; these regions share more than 80% sequence similarity. The regions of poorest homology are the loops representing the upper surface of the second and third propeller blades. Coordinates were assigned to the αIIb β-propeller using the Homology module of InsightII. Where the sequences of αV and αIIb were identical, coordinates were simply assigned. Most of the nonhomologous regions were short (3-5 residue) loops. For each of these segments, a minimum of 20 short loop structures was generated that included at least 4 homologous residues flanking the loop at each end. Loops were chosen for the model that had the lowest energy and best superposition with the flanking residues whose coordinates had already been assigned. The 3 remaining nonhomologous regions were 3 larger loops, namely the 4-1 and 2-3 loops of blade 2 and the 4-1 loop of blade 3; because these loops are larger, more loop structures were generated (a minimum of 50) with at least 6 flanking residues on each end. Because these last 3 loops are above the propeller and thus furthest away from the calcium-binding domains, no further structural refinement was performed. Energy minimization was carried out on this final model in successive steps using InsightII. First, the splicing sites between the homologous regions and nonhomologous loops were energy minimized using the steepest descent method with a force constant to close the gaps and backbone angle constraints to conserve appropriate side-chain orientation. Then the inserted loops themselves were minimized, also using the steepest descent method. After this step, the CHARMM force field was used for final energy minimization using the Adopted Basis Newton-Raphson method.33 For evaluation of mutational defects, the individual amino acids were changed in the αIIb β-propeller model and energy was minimized again with the Adopted Basis Newton-Raphson method using CHARMM. Two sets of electrostatic potentials were calculated using CHARMM, one set using a constant dielectric and another set using a distance-dependent dielectric. All calculations were carried out in vacuo.

Results

Platelet surface receptor and immunoblot analyses

Patient M.

To assess the surface expression of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 receptors on the patient's platelets, radiolabeled antibody-binding studies were performed. The bindings of the anti-GPIbα mAb 6D1 to the platelets of patient M, his father, and his mother were 151%, 119%, and 93%, respectively, of the control value (Table3). The bindings of antibodies 10E5 (anti-αIIbβ3) and c7E3 Fab (anti-αIIbβ3 + αVβ3) to the platelets of patient M were 6% and 3% of normal, respectively. The binding of these antibodies to the platelets of the patient's parents ranged from 39% to 67% of normal. The binding of antibody LM609 (anti-αVβ3) to the platelets of patient M, his father, and his mother was 114%, 78%, and 113% of normal, respectively. The reduced binding of antibodies to αIIbβ3 and the normal/increased binding of antibodies to αVβ3 indicate an abnormality in αIIb.

Platelet surface receptors

| Family members . | 6D13-150anti-GPIb . | 10E5 anti-αIIbβ3 . | 7E3 anti-αIIbβ3 + αvβ3 . | LM609 anti-αvβ3 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient M | 151 | 6 | 3 | 117 |

| Father | 119 | 58 | 67 | 78 |

| Mother | 93 | 39 | 52 | 113 |

| Patient C | 125 | 7 | 8 | 130 |

| Father | 117 | 7 | 9 | 65 |

| Mother | 92 | 54 | 56 | 100 |

| Sibling-1 | 109 | 7 | 8 | 108 |

| Sibling-2 | 121 | 8 | 10 | 125 |

| Family members . | 6D13-150anti-GPIb . | 10E5 anti-αIIbβ3 . | 7E3 anti-αIIbβ3 + αvβ3 . | LM609 anti-αvβ3 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient M | 151 | 6 | 3 | 117 |

| Father | 119 | 58 | 67 | 78 |

| Mother | 93 | 39 | 52 | 113 |

| Patient C | 125 | 7 | 8 | 130 |

| Father | 117 | 7 | 9 | 65 |

| Mother | 92 | 54 | 56 | 100 |

| Sibling-1 | 109 | 7 | 8 | 108 |

| Sibling-2 | 121 | 8 | 10 | 125 |

Expressed as percent of normal.

By immunoblot analysis, both αIIb and β3 subunits were detected in the patient's platelet lysates, but at reduced levels compared to a healthy control and samples from both parents (Figure1A). Mature αIIb subunits were detected, indicating normal processing of αIIb.

Immunoblots of platelet αIIb and β3 for patients M and C.

Platelets were solubilized in SDS, electrophoresed into a 7% polyacrylamide gel under reduced (αIIb) and nonreduced (β3) conditions, and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes. Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed as judged by the staining of the gel after electrophoresis for platelet myosin heavy chain (Mr about 200 000). Membranes analyzed for αIIb were incubated with the mAb PMI-1, and membranes analyzed for β3 were incubated with the mAb 7H2.28 (A) Samples from patient M and his mother and father. (B) Samples from patient C and his 2 siblings.

Immunoblots of platelet αIIb and β3 for patients M and C.

Platelets were solubilized in SDS, electrophoresed into a 7% polyacrylamide gel under reduced (αIIb) and nonreduced (β3) conditions, and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes. Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed as judged by the staining of the gel after electrophoresis for platelet myosin heavy chain (Mr about 200 000). Membranes analyzed for αIIb were incubated with the mAb PMI-1, and membranes analyzed for β3 were incubated with the mAb 7H2.28 (A) Samples from patient M and his mother and father. (B) Samples from patient C and his 2 siblings.

Patient C.

To assess the surface expression of αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 receptors on the platelets of patient C, the same radiolabeled antibody-binding studies were performed. The bindings of the anti-GPIbα mAb 6D1 to the platelets of the patient, his father, mother, and 2 siblings were 125%, 117%, 92%, 109%, and 121%, respectively, of the control value (Table 3). The bindings of antibodies 10E5 (anti-αIIbβ3) and c7E3 Fab (anti-αIIbβ3 + αVβ3) to the platelets of patient C were 7% and 8% of normal. Interestingly, the binding of antibodies 10E5 and 7E3 to the platelets of the patient's father and 2 siblings was also 10% or less of normal, whereas the binding of these antibodies to the platelets of the patient's mother were 54% and 56% of normal, respectively. The binding of antibody LM609 (anti-αVβ3) to the platelets of the patient and his family members was normal. These data are consistent with abnormalities in αIIb in the patient, his father, and 2 siblings.

By immunoblot analysis, it was found that the platelets of the patient and his 2 siblings contained both αIIb and β3, but at reduced levels compared with a healthy control (Figure 1B). In all samples, mature αIIb subunits were present, suggesting that pro-αIIbβ3 complexes did form and that pro-αIIb was processed during maturation of the receptor complex.

Mutation identification for patients M and C

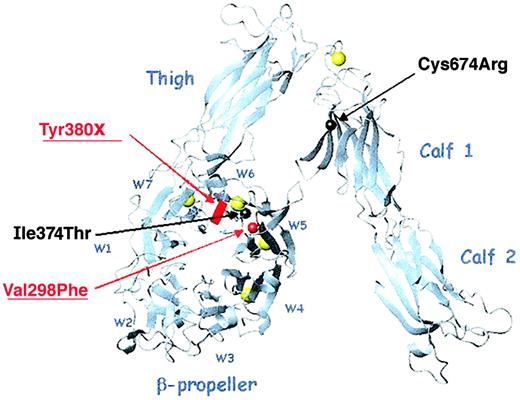

Direct sequence analyses of the genes encoding αIIb were performed on DNA isolated from leukocytes obtained from both patients and family members. Both patients are compound heterozygotes and the relative locations of each of their mutations is shown in a ribbon diagram of αV (Figure 2). Patient M inherited a Val298Phe missense mutation from his mother and a Tyr380X nonsense mutation from his father. The Val298Phe mutation, located in the second calcium-binding domain (propeller blade 5), was created by a G>T nucleotide substitution at position 985 of the pro-αIIb sequence encoded by exon 11. The Tyr380X mutation, located between the third and fourth calcium-binding domains, was created by an adenine nucleotide insertion at position 1233 of the pro-αIIb sequence encoded by exon 13. This insertion creates a TAA stop codon at amino acid Tyr380. Patient C inherited an Ile374Thr missense mutation from his mother and a Cys674Arg mutation from his father. The Ile374Thr mutation, located in the third calcium-binding domain (blade 6), was created by a T>C nucleotide substitution at position 1214 of the pro-αIIb sequence encoded by exon 13. The Cys674Arg mutation was created by a T>C nucleotide substitution at position 2113 of the pro-αIIb sequence encoded by exon 21. Sequence analyses of DNA from the father and 2 siblings of patient C showed that his father was homozygous for the Cys674Arg missense mutation and both siblings were compound heterozygous for the Cys674Arg and Ile374Thr missense mutations (data not shown).

Ribbon diagram of the αV subunit showing the relative locations of the αIIb mutations of patients M and C.

The αIIb and αV subunits share 40% sequence homology. This ribbon diagram of αV shows the relative positions of the 4 αIIb mutations, which are indicated by spheres (missense mutation) or a block (nonsense mutation) centered on the amino acid α-carbons (red and underlined for patient M, black for patient C). The β-propeller blades are designated W1-W7; the calcium atoms are shown in yellow. Three mutations lie within the β-propeller domain, blades W5 and W6, and the fourth is within the calf-1 domain. This image was generated with MOLMOL36 from the PDB file 1JV2.13

Ribbon diagram of the αV subunit showing the relative locations of the αIIb mutations of patients M and C.

The αIIb and αV subunits share 40% sequence homology. This ribbon diagram of αV shows the relative positions of the 4 αIIb mutations, which are indicated by spheres (missense mutation) or a block (nonsense mutation) centered on the amino acid α-carbons (red and underlined for patient M, black for patient C). The β-propeller blades are designated W1-W7; the calcium atoms are shown in yellow. Three mutations lie within the β-propeller domain, blades W5 and W6, and the fourth is within the calf-1 domain. This image was generated with MOLMOL36 from the PDB file 1JV2.13

The Val298Phe mutation of patient M and the Ile374Thr mutation of patient C are the first to be reported within the second and third calcium-binding domains of the αIIb subunit. The other 2 mutations were not further characterized. The Tyr380X mutation in patient M presumably results in a truncated protein of about 42 kDa. Because the anti-αIIb mAb we used, PMI-1, recognizes an epitope distal to this region of αIIb,34 we would not detect such a fragment; thus, we are uncertain as to the biosynthesis and stability of such a fragment. The Cys674Arg mutation in patient C has been characterized in another patient with Glanzmann thrombasthenia and was shown to affect receptor biogenesis, resulting in about 10% of normal levels of surface expression.35

Expression of mutant αIIbβ3 receptors in mammalian cells

Mutant receptor expression on the cell surface of transfected 293T cells was very low. Thus, only 13% ± 5% of cells expressing the αIIbVal298Phe mutation were positive by flow cytometry using the anti-αIIbβ3 mAb 10E5, and only 5% ± 3% of cells expressing the αIIbIle374Thr mutation were positive. In sharp contrast, 46% ± 12% of cells transfected with the normal receptors were positive by flow cytometry (data not shown).

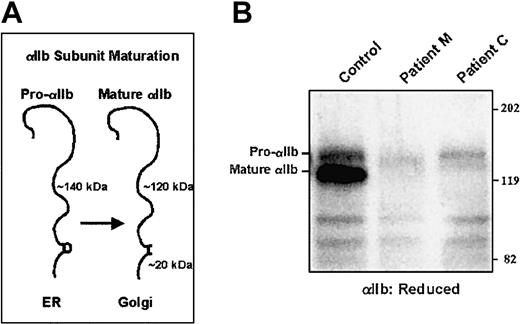

To analyze the levels of pro-αIIb subunits expressed in 293T cells transfected with normal and mutant αIIbβ3 receptors, protein analyses were performed. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-αIIb mAbs that recognize pro-αIIb and mature αIIb subunits. To identify mature αIIb subunits, the samples were electrophoresed under reduced conditions and immunoblotted with an anti-αIIb mAb (Figure 3). The majority of αIIb subunits in cells expressing normal αIIbβ3 receptors were processed to mature αIIb. In cells expressing either the Val298Phe or the Ile374Thr αIIb mutations, αIIb expression was dramatically reduced and only pro-αIIb subunits were detected. Because surface expression of both mutants was very low, as judged by flow cytometry, we infer that the proteins seen on immunoblot most likely represent defective αIIb subunits that are retained in the cell.

Immunoblot for αIIb of 293T cells transfected with mutant αIIbβ3 receptors.

Cells were solubilized in Triton X-100, electrophoresed into a 7% polyacrylamide gel under reduced conditions, and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes. Equal amounts of protein (150 μg), as determined by the BCA assay, were loaded per lane. The membrane was analyzed for αIIb using the mAb PMI-1. (A) Schematic diagram showing the processing and molecular weights of pro-αIIb in the endoplasmic reticulum and of mature αIIb in the Golgi. (B) Immunoblot of αIIb showing pro-αIIb and mature forms of control and mutant subunits.

Immunoblot for αIIb of 293T cells transfected with mutant αIIbβ3 receptors.

Cells were solubilized in Triton X-100, electrophoresed into a 7% polyacrylamide gel under reduced conditions, and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes. Equal amounts of protein (150 μg), as determined by the BCA assay, were loaded per lane. The membrane was analyzed for αIIb using the mAb PMI-1. (A) Schematic diagram showing the processing and molecular weights of pro-αIIb in the endoplasmic reticulum and of mature αIIb in the Golgi. (B) Immunoblot of αIIb showing pro-αIIb and mature forms of control and mutant subunits.

Pulse-chase analyses were performed to assess the mechanisms responsible for the reduced levels of mutant αIIb (Figure4). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-αIIb mAbs that recognize pro-αIIb and mature αIIb subunits. Cells expressing normal αIIbβ3 receptors show a normal maturation pattern. At time 0, only pro-αIIb and trace amounts of β3 subunits are detectable. By 2 hours, mature αIIb heavy-chain subunits are detectable, showing that pro-αIIb subunits have undergone processing and cleavage to form heavy and light chains. By 24 hours, only mature αIIbβ3-receptor complexes are detectable. The same analyses were performed on cells expressing αIIbβ3 receptors containing the Val298Phe and Ile374Thr mutations. In both cases, only pro-αIIb subunits were detected, and only at the early time points, suggesting that they were retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and subsequently degraded.

Pulse-chase analysis of transfected cells expressing control and mutant αIIbβ3 receptors.

Cells were cotransfected with cDNA constructs expressing control or mutant (Val298Phe and Ile374Thr) αIIb and control β3 subunits for 36 hours. Following preincubation in methionine/cysteine-free medium, cells were labeled with 35S-methionine/cysteine (300 μCi/well [11.1 MBq]) containing medium for 15 minutes and chased in medium containing methionine and cysteine (1 mg/mL each). Cells were harvested at the indicated time points. Using equivalent TCA precipitable counts (about 1.5 × 106 counts/sample), cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using a combination of αIIb-specific mAbs, B1B530 31 and M-148 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 4 μg each/sample) that recognize pro-αIIb and mature αIIb subunits. Samples were electrophoresed under reduced conditions and dried gels were exposed to film. Bands representing pro-αIIb, mature αIIb, and β3 are shown by arrows.

Pulse-chase analysis of transfected cells expressing control and mutant αIIbβ3 receptors.

Cells were cotransfected with cDNA constructs expressing control or mutant (Val298Phe and Ile374Thr) αIIb and control β3 subunits for 36 hours. Following preincubation in methionine/cysteine-free medium, cells were labeled with 35S-methionine/cysteine (300 μCi/well [11.1 MBq]) containing medium for 15 minutes and chased in medium containing methionine and cysteine (1 mg/mL each). Cells were harvested at the indicated time points. Using equivalent TCA precipitable counts (about 1.5 × 106 counts/sample), cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using a combination of αIIb-specific mAbs, B1B530 31 and M-148 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 4 μg each/sample) that recognize pro-αIIb and mature αIIb subunits. Samples were electrophoresed under reduced conditions and dried gels were exposed to film. Bands representing pro-αIIb, mature αIIb, and β3 are shown by arrows.

Determining the role of the hydrophobic amino acids Val298 and Ile374 in αIIbβ3 biogenesis

Because the Val298Phe and Ile374Thr mutations disrupt biogenesis of the receptor complex, additional amino acid substitutions were analyzed at these sites. Figure 5A shows a schematic of an αIIb calcium-binding loop, including the 3 residues proximal to the loop (−3, −2, −1), and the relative locations of the patients' Val298Phe and Ile374Thr substitutions. The additional mutations that were created at these sites are shown in the boxes.

Effect of replacing residues Val298 and Ile374 with different amino acids on the maturation and processing of pro-αIIb to mature αIIb.

Cells were cotransfected with cDNA constructs expressing control or mutant αIIb and control β3 subunits for 36 hours. Whole cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with antibodies to αIIb (B1B5 and M-148). Immunoblots were performed with another antibody to αIIb (PMI-1). Bands representing pro-αIIb and mature αIIb are shown by arrows. (A) Schematic model of a calcium-binding loop showing residues numbered −3 to −1 and 1-12. The amino acid sequences of the second and third calcium-binding domains of αIIb are shown. The Val298 and Ile374 residues are underlined and the amino acids in the putative N-linked glycosylation site created by the Ile374Thr mutation are bracketed. The amino acid substitutions for residues Val298, Ile374, and Asn372 are shown in the boxes. (B) Immunoblot of cells expressing amino acid substitutions for residue Val298. (C) Immunoblot of cells expressing amino acid substitutions for residue Ile374. (D) Immunoblot of cells expressing amino acid substitutions for Ile374 and Asn372.

Effect of replacing residues Val298 and Ile374 with different amino acids on the maturation and processing of pro-αIIb to mature αIIb.

Cells were cotransfected with cDNA constructs expressing control or mutant αIIb and control β3 subunits for 36 hours. Whole cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with antibodies to αIIb (B1B5 and M-148). Immunoblots were performed with another antibody to αIIb (PMI-1). Bands representing pro-αIIb and mature αIIb are shown by arrows. (A) Schematic model of a calcium-binding loop showing residues numbered −3 to −1 and 1-12. The amino acid sequences of the second and third calcium-binding domains of αIIb are shown. The Val298 and Ile374 residues are underlined and the amino acids in the putative N-linked glycosylation site created by the Ile374Thr mutation are bracketed. The amino acid substitutions for residues Val298, Ile374, and Asn372 are shown in the boxes. (B) Immunoblot of cells expressing amino acid substitutions for residue Val298. (C) Immunoblot of cells expressing amino acid substitutions for residue Ile374. (D) Immunoblot of cells expressing amino acid substitutions for Ile374 and Asn372.

Cells expressing receptors with either the Val298Phe mutation of patient M or the Val298Ala amino acid substitution show similar results, with greatly reduced levels of mature αIIb and a small amount of pro-αIIb (Figure 5B). In sharp contrast, cells expressing receptors containing the Val298Leu amino acid substitution had a level of mature αIIb similar to that of the control cells. These data show that replacing the branched-chain hydrophobic amino acid valine with the structurally similar leucine residue maintains αIIb maturation, but replacement with a smaller hydrophobic residue, such as alanine, or the bulkier hydrophobic phenylalanine, with its aromatic side chain, prevents αIIb maturation.

Cells expressing receptors with the Ile374Thr mutation of patient C had a markedly reduced level of pro-αIIb and virtually no mature αIIb (Figure 5C). Replacement of the branched-chain hydrophobic amino acid isoleucine with leucine or valine resulted in the expression of near-normal levels of mature αIIb subunits. Pro-αIIb was also detected in the Ile374Leu and Ile374Val mutants at levels greater than control, but the percentage of αIIb in the pro-αIIb form relative to mature was dramatically reduced when compared with the Ile374Thr mutation. Because isoleucine is the largest of the branched-chain amino acids, and because leucine and valine rescued αIIb maturation only partially, the large branched-side chain of isoleucine is likely to be a key structural requirement at this position.

The pro-αIIb subunits containing the Ile374Thr amino acid substitution migrated slightly slower in SDS-PAGE than the normal pro-αIIb subunits (Figure 5C-D), raising the possibility that the new N-linked glycosylation site created by the mutation (Figure 5A) is actually glycosylated. To explore this possibility further, 2 additional cDNA constructs were made: (1) Ile374Ser, which also creates an N-linked glycosylation site, and (2) Asn372Gln/Ile374Thr, which does not create an N-linked glycosylation site, but retains both the charge of the N and the patient's Ile374Thr mutation. Cells expressing receptors with the Ile374Ser substitution, like those with the patient's Ile374Thr substitution, showed only pro-αIIb subunits that migrated slower than control (Figure 5D). Cells expressing receptors with both the Ile374Thr mutation of patient C and the additional Asn372Gln substitution had pro-αIIb subunits that migrated normally, but no mature αIIb was detected. Because the elimination of the newly created N-linked glycosylation site did not restore maturation of the pro-αIIb subunit, these data show that the biosynthetic defect of patient C is due to the Ile374Thr amino acid substitution, and not additional glycosylation.

Surface expression of mutant receptors

To assess whether the amino acid substitutions that restored αIIb maturation also restored surface expression of αIIbβ3 complexes, flow cytometry was performed using the complex-dependent mAb, 10E5 (Figure 6). Receptors were detected on 33% of the control cells, whereas less than 10% of the cells transfected with Val298Phe or Ile374Thr bound 10E5. With the Val298Leu, Ile374Leu, and Ile374Val αIIb substitutions, all of which are branched-chain hydrophobic residues, αIIbβ3 was detected on 22%, 20%, and 31% of cells, respectively.

Effect of replacing αIIb residues Val298 and Ile374 with different amino acids on the surface expression of αIIbβ3 receptors.

Flow cytometry was performed on 293T cells cotransfected with αIIb constructs containing control, Val298 and Ile374, or substituted (Val298Phe, Val298Leu, Ile374Thr, Ile374Leu, Ile374Val) amino acid residues and a control β3 construct. Cells were incubated with the complex-dependent mAb, 10E5, then with FITC-labeled secondary antibody (shaded) and flow cytometry was performed. Background controls were cells incubated with secondary antibody alone (unshaded). Percentages indicate percent positive of gated cells.

Effect of replacing αIIb residues Val298 and Ile374 with different amino acids on the surface expression of αIIbβ3 receptors.

Flow cytometry was performed on 293T cells cotransfected with αIIb constructs containing control, Val298 and Ile374, or substituted (Val298Phe, Val298Leu, Ile374Thr, Ile374Leu, Ile374Val) amino acid residues and a control β3 construct. Cells were incubated with the complex-dependent mAb, 10E5, then with FITC-labeled secondary antibody (shaded) and flow cytometry was performed. Background controls were cells incubated with secondary antibody alone (unshaded). Percentages indicate percent positive of gated cells.

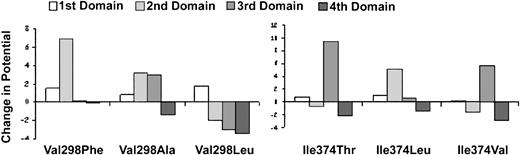

The Val298Phe and Ile374Thr mutations adversely affect the electrostatic potentials of the calcium-binding domains as judged by a molecular model of the αIIb β-propeller

Because calcium binding is dependent on electrostatic interactions, we could assess the potential effects of the calcium-binding domain mutations on calcium binding in a molecular model by calculating their effects on the electrostatic potential at the calcium positions in the domains (Figure7). An increase in potential (more positive charge) would decrease the domain's ability to bind calcium, whereas a decrease in potential (more negative charge) would increase the domain's ability to bind calcium. The Val298Phe and Ile374Thr mutations resulted in striking increases in electrostatic potential at the second and third calcium positions, respectively, with little effect on the potentials at the other calcium positions. These data suggest that both mutations impair calcium binding. The Val298Ala mutation, which did not rescue the expression of αIIbβ3, resulted in increased electrostatic potentials at the second and third calcium positions, with a minimal decrease in electrostatic potential at the fourth calcium position. In contrast, the Val298Leu mutation, which rescued αIIbβ3 expression, not only prevented the increased electrostatic potential caused by the Val298Phe mutation at the second calcium position, but actually decreased the potential relative to control at the third and fourth calcium positions.

Effect of αIIb mutations on electrostatic potential.

The electrostatic potential was calculated at each of the 4 calcium positions in the αIIb β-propeller model. The Glanzmann thrombasthenia mutations Val298Phe and Ile374Thr, and the experimental mutations Val298Ala, Val298Leu, Ile374Leu, and Ile374Val were then inserted into the model and the electrostatic potentials were calculated. The relative change in electrostatic potential resulting from each mutation is depicted for each calcium position as a positive or negative bar. The normal electrostatic potential at each calcium position is arbitrarily set to 0. A positive change in electrostatic potential of more than 2 (the charge of calcium) would be expected to decrease the ability of calcium to bind, whereas a negative change in electrostatic potential would increase the ability of calcium to bind.

Effect of αIIb mutations on electrostatic potential.

The electrostatic potential was calculated at each of the 4 calcium positions in the αIIb β-propeller model. The Glanzmann thrombasthenia mutations Val298Phe and Ile374Thr, and the experimental mutations Val298Ala, Val298Leu, Ile374Leu, and Ile374Val were then inserted into the model and the electrostatic potentials were calculated. The relative change in electrostatic potential resulting from each mutation is depicted for each calcium position as a positive or negative bar. The normal electrostatic potential at each calcium position is arbitrarily set to 0. A positive change in electrostatic potential of more than 2 (the charge of calcium) would be expected to decrease the ability of calcium to bind, whereas a negative change in electrostatic potential would increase the ability of calcium to bind.

The Ile374Leu mutation, which rescued αIIbβ3 expression, eliminated the increased electrostatic potential caused by the Ile374Thr mutation at the third calcium position, but it did increase the potential at the second calcium position. The Ile374Val mutation, which also rescued αIIbβ3 expression, partially reduced the increase in electrostatic potential at the third calcium position, and decreased the electrostatic potential at the fourth calcium position.

Discussion

We have characterized 2 new αIIb calcium-binding domain mutations in patients with Glanzmann thrombasthenia and have identified structural elements within the calcium-binding domains that are essential for both maintaining an electrostatic potential conducive to calcium binding and for αIIbβ3-receptor biogenesis. Both the Val298Phe and the Ile374Thr mutations result in the expression of pro-αIIb subunits that are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and degraded. Mutagenesis studies show that other branched-chain amino acids can substitute for valine at residue 298 (position 2 of the second calcium-binding domain), and for isoleucine at residue 374 (position 10 of the third calcium-binding domain). However, neither the larger phenylalanine nor the smaller alanine can substitute for valine at position 298, indicating stringent structural specifications for this position. The Ile374Thr mutation creates a new N-linked glycosylation site, but our data show that αIIbβ3 biogenesis is disrupted by the amino acid substitution, and not the additional glycosylation. Both mutations lie within clusters of highly conserved hydrophobic residues within the αIIb calcium-binding domains. Because the mutated residues are hydrophobic, their side chains are unable to directly participate in calcium coordination. However, calculations using a molecular model of αIIb show that both Glanzmann mutations dramatically affect the electrostatic potential in their respective calcium-binding domains, and that these changes are corrected by mutations that rescue αIIbβ3 expression. Together these data suggest that these 2 new mutations disrupt αIIb biogenesis by altering the structure of the calcium-binding domains and interfering with calcium binding, thereby disrupting a critical role played by the domains in biogenesis.

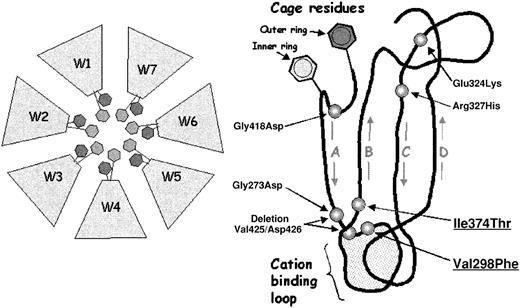

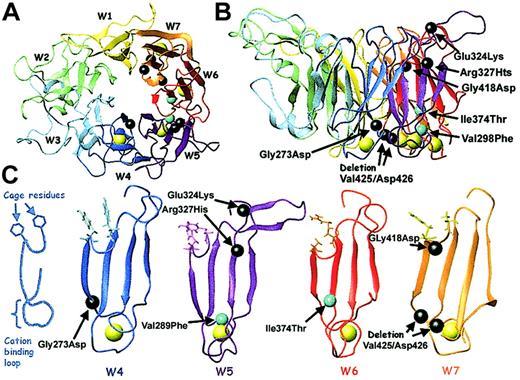

By using the molecular model of the αIIb β-propeller, previous findings regarding mutations within or near the calcium-binding domains may now be re-examined in light of their structural proximity to both the calcium-binding domains and to the cage motif. Figure 8 is a schematic of the β-propeller domain of αIIb showing the top of the β-propeller and the relative positions of the aromatic cage residues.

Mutations within the αIIb calcium-binding domains.

(Left) Schematic of the β-propeller domain of αIIb and αv showing the central cage motif. The blades are labeled W1 through W7. The cage motif comprises 2 concentric rings of predominantly aromatic residues, which line the upper, inner rim of the propeller core. Each blade contributes 2 residues to the cage structure, represented here by hexagons. (Right) Schematic of one blade of the αIIb β-propeller derived from molecular modeling, showing the relative locations of 7 Glanzmann thrombasthenia mutations that lie within blades W4-W7. The blade is viewed from the side, with the 2 cage residues indicated and the calcium-binding loop at the bottom. Starting from the cage residues, the 4 antiparallel β-strands of the blade form the legs of a “W.” Seven mutations reported to be in or near the calcium-binding domains (including the 2 from this study, underlined) are shown in their relative positions: Gly273Asp from W4; Val298Phe, Glu324Lys, and Arg327His from W5; Ile374Thr from W6; and Gly418Asp and deletion Val425/Asp426 from W7.7-11

Mutations within the αIIb calcium-binding domains.

(Left) Schematic of the β-propeller domain of αIIb and αv showing the central cage motif. The blades are labeled W1 through W7. The cage motif comprises 2 concentric rings of predominantly aromatic residues, which line the upper, inner rim of the propeller core. Each blade contributes 2 residues to the cage structure, represented here by hexagons. (Right) Schematic of one blade of the αIIb β-propeller derived from molecular modeling, showing the relative locations of 7 Glanzmann thrombasthenia mutations that lie within blades W4-W7. The blade is viewed from the side, with the 2 cage residues indicated and the calcium-binding loop at the bottom. Starting from the cage residues, the 4 antiparallel β-strands of the blade form the legs of a “W.” Seven mutations reported to be in or near the calcium-binding domains (including the 2 from this study, underlined) are shown in their relative positions: Gly273Asp from W4; Val298Phe, Glu324Lys, and Arg327His from W5; Ile374Thr from W6; and Gly418Asp and deletion Val425/Asp426 from W7.7-11

The cage motif is comprised of 2 concentric rings of predominantly aromatic residues, which line the upper, inner rim of the propeller core. Each blade contributes 2 residues to the cage structure. The 4 antiparallel β strands of each blade form the legs of a “W.” The β sheet begins at the inner blade edge with the 2 aromatic cage residues. The first strand (A) feeds directly into the calcium-binding loop and the remaining 3 strands (B-D) form the β sheet and outer blade edge. Seven mutations reported to be in or near the calcium-binding domains (including the 2 from this study) are shown in their relative positions: Gly273Asp from W4; Val298Phe, Glu324Lys, and Arg327His from W5; Ile374Thr from W6; and Gly418Asp and deletion Val425/Asp426 from W7.7-11

A molecular model of the αIIb β-propeller was constructed to analyze the structural effects of the calcium-binding domain mutations (Figure 9). The 2 mutations reported in this paper and the Gly273Asp7 mutation lie within the highly conserved hydrophobic regions flanking the calcium-binding β-hairpin loops. These presumably exert their effects by disrupting the β-hairpin loop stability. The fourth mutation, deletion Val425/Asp426,10 deletes the primary calcium-coordination residue, Asp426, and has been shown to disrupt calcium binding.37 The Gly418Asp8 mutation falls within the highly conserved cage structure and eliminates the universally conserved glycine hinge separating the inner and outer ring residues. This mutation was also shown to disrupt calcium binding.37 The finding that this relatively distant mutation (8 residues away and on the opposite propeller face) profoundly affects calcium binding is evidence of the structural intimacy between the calcium binding loops and the cage motif.

Model of the αIIb β-propeller showing calcium-binding mutations and cage residues.

A model of the αIIb β-propeller was generated as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” (A) Top view of the propeller showing the 7 blades (W1-W7), the 4 calcium ions (yellow), and the locations of 7 reported calcium-binding domain mutations (black and cyan spheres; mutations identified in this study are cyan). (B) Side view of the propeller with the mutations labeled. (C) Blades W4-W7 are viewed from the side. The 2 critical cage residues are displayed. A sphere centered on the amino acid α-carbon identifies the positions of each calcium-binding domain mutation. This figure was generated with MOLMOL.36

Model of the αIIb β-propeller showing calcium-binding mutations and cage residues.

A model of the αIIb β-propeller was generated as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” (A) Top view of the propeller showing the 7 blades (W1-W7), the 4 calcium ions (yellow), and the locations of 7 reported calcium-binding domain mutations (black and cyan spheres; mutations identified in this study are cyan). (B) Side view of the propeller with the mutations labeled. (C) Blades W4-W7 are viewed from the side. The 2 critical cage residues are displayed. A sphere centered on the amino acid α-carbon identifies the positions of each calcium-binding domain mutation. This figure was generated with MOLMOL.36

Our calculations of electrostatic potential suggest that both the Val298Phe and Ile374Thr mutations disrupt calcium binding in their respective domains by increasing the local electrostatic potential. Conversely, the Val298Leu and both Ile374Leu and Ile374Val mutations reverse the electrostatic effects of the Val298Phe and Ile374Thr mutations, respectively. The αIIb and αV propeller regions share 68% homology, with more than 80% homology in the calcium-binding regions. Therefore, our model is likely to have the greatest accuracy in these regions. The major structural differences between αIIb and αV lie in the upper loops of W2 and W3: the 4-1 and 2-3 loops of blades W2 and the 4-1 loop of W3. Interestingly, these same loops are implicated in ligand binding.40

The α-integrin calcium-binding domains have all of the structural characteristics of β-hairpin loops, consisting of a charged loop with a glycine hinge, flanked by groups of hydrophobic residues.15 Branched-chain hydrophobic residues are highly conserved at positions 2 and 10-12 in all 18 of the currently identified integrin α subunits.41-50 The β-hairpin loops play important roles in protein folding and stability, enhancing the folding rate and structural stability of entire β-sheet structures.16 The β-hairpin turns are stabilized by both hydrogen bonding between the strand backbones and by hydrophobic interactions among the flanking residues.51 The mutations at positions Val298 and Ile374 fall within the highly conserved clusters of hydrophobic residues flanking the αIIb calcium-binding domains, and thus it is likely that the mutations exert their effects by destabilizing the β-hairpin loops. Based on data from other systems,52 it is likely that in the calcium-rich lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, nascent calcium-binding domains are likely to fold around the available calcium ions immediately upon translocation.53 Thus, the β-hairpin calcium-binding domains may be crucial for the proper folding of the entire β-propeller, which is the site of interaction between the α- and β-integrin subunits.

An intimate structural relationship is also apparent between the calcium-binding domains and the novel cage motif, which forms the central contact point between the 2 subunits. The cage structure is comprised of 2 concentric rings of aromatic residues encircling the top rim of the central propeller pore. Each propeller blade contributes 2 hydrophobic residues to each ring (Figure 8). Arg261 of the β3-A domain extends through the rings of aromatic residues and is captured by hydrophobic interactions with the aromatic residues.13Because the Val298Phe and Ile374Thr mutations do not introduce any changes in charge, the observed changes in electrostatic potential represent a subtle repositioning of the side chains in the surrounding regions, which includes the cage motif. Consequently, structural disruption of the calcium-binding loops could result in structural alterations of the cage motif that affect the conformation and stability of the αIIb-β3 interface. In support of this hypothesis is the observation that none of the α-β heterodimers containing the Val298Phe, Ile374Thr, Gly273Asp, Gly418Asp, or deletion Val425/Asp426 mutations were recognized by complex-dependent mAbs, even though they do not prevent coimmunoprecipitation of the α-β heterodimer by subunit-specific mAbs.7,8 10 This indicates that although these mutant αIIb subunits can form a complex with β3, the complexes are not in their native conformations.

Previously, the effects of 3 Glanzmann thrombasthenia mutations (Figures 8-9: Gly273Asp, Gly418Asp, deletion Val425/Asp426) on calcium binding were analyzed by terbium luminescence.37 Short polypeptides were generated that represented the individual αIIb calcium-binding domains with and without the mutations. Based on the techniques of Cierniewski,38 tyrosine and tryptophan residues were substituted at positions 7 and 11 of each of the calcium-binding domains in the peptides to enhance the luminescence energy of the bound terbium. The Gly418Asp and deletion Val425/Asp426 mutations both resulted in loss of terbium luminescence, reflecting loss of calcium binding. When these mutations were tested in longer peptides that comprised all 4 calcium-binding domains, they also abrogated calcium binding. No change in terbium luminescence was noted, however, in the Gly273Asp peptide, which was interpreted as indicating that the mutation did not result in defective calcium binding. This finding is contradictory to the findings of the present study, in that the Gly273Asp mutation inserts a charged residue into the hydrophobic cluster of residues flanking the first calcium-binding domain. Calculations based on our molecular model suggest that such a mutation would disrupt calcium binding. We believe, however, that our data and those regarding the Gly273Asp mutation can be reconciled based on 2 considerations.

First, the Gly273Asp mutant was only tested in the short peptide, and thus it was not subjected to the steric interactions that accompany the close packing in the propeller region. Second, the tyrosine to tryptophan substitution made at position 11 to enhance terbium luminescence may have affected the results. In both αV and our model of αIIb the hydrophobic residues at positions −1 and 11 in the β-hairpin calcium-binding loops are close enough to interact (Figure 5A). The Gly273Asp substitution places an aspartic acid at position −1, which would not be expected to interact with the tyrosine at position 11. However, aspartic acid can interact with the imino group of tryptophan.39 Thus, the tryptophan substitution may have inadvertently prevented the Gly273Asp mutation from disrupting cation binding.

In conclusion, through combining protein expression and mutagenesis studies with the newly available crystal structure data and molecular modeling, we have identified structural elements of the α-integrin calcium-binding domains that are essential for both calcium binding and αIIbβ3-receptor biogenesis. This study supports the hypothesis that the calcium-binding domains play an essential structural role in integrin biogenesis by facilitating the early folding process of αIIb and conferring stability to the cage motif during αIIbβ3-heterodimer formation.

We thank Drs Ginsberg, Poncz, and Newman for the generous supply of monoclonal antibodies. We are grateful to Drs Harel Weinstein, Ernest Mehler, and Mihaly Mezei in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, for the use of their computer facility and assistance with molecular modeling software.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 7, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2266.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant HL 19278 (B.S.C.); American Heart Association Heritage Affiliate Ilma F. Kern Foundation in honor of John Halperin, MD; The Charles Slaughter Foundation (D.L.F); and a fellowship from an Institutional National Research Service Award, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute T32 HL07824-06 (to W.B.M.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Deborah L. French, Box 1079 Hematology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1 Gustave L. Levy Pl, New York, NY 10029; e-mail: debbie.french@mssm.edu.

![Fig. 4. Pulse-chase analysis of transfected cells expressing control and mutant αIIbβ3 receptors. / Cells were cotransfected with cDNA constructs expressing control or mutant (Val298Phe and Ile374Thr) αIIb and control β3 subunits for 36 hours. Following preincubation in methionine/cysteine-free medium, cells were labeled with 35S-methionine/cysteine (300 μCi/well [11.1 MBq]) containing medium for 15 minutes and chased in medium containing methionine and cysteine (1 mg/mL each). Cells were harvested at the indicated time points. Using equivalent TCA precipitable counts (about 1.5 × 106 counts/sample), cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using a combination of αIIb-specific mAbs, B1B53031 and M-148 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 4 μg each/sample) that recognize pro-αIIb and mature αIIb subunits. Samples were electrophoresed under reduced conditions and dried gels were exposed to film. Bands representing pro-αIIb, mature αIIb, and β3 are shown by arrows.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/6/10.1182_blood-2002-07-2266/4/m_h80633989004.jpeg?Expires=1764955700&Signature=OS843V6Xcs~aJvtvOBRwpED7O8DKgGRWAfi7w2wJQ7Y2y86Sb-wx~0lDD-nP3aqcEWpZvzpxP1fS3t1h-9lyuEwoRl2T3lTmq23hXRa2mhrx~tODxX2L9CmwbonKsgSKyxnjuARfkd08ZCNO0oFP7aDdqKar8IUkUHOU3wpWnjN-7kbzKXFkr-PF0dsf7o9-bcT--ytzC16nLaP3AurZCsaJIClNVbxFRt1WlRhhGgpf8Ybj5dTKqiK52OjT8QLy3klKKVqYtP-vwSiUqkmRaHoPu5quVqbvUOHBbmmzAgZ9P9bvA0iBOS1O-jAmzpXDz-bFBHWGD8bHFBue1unIJg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal