Abstract

Because of the central role of the transcription factor nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB) in cell survival and proliferation in human multiple myeloma (MM), we explored the possibility of using it as a target for MM treatment by using curcumin (diferuloylmethane), an agent known to have very little or no toxicity in humans. We found that NF-κB was constitutively active in all human MM cell lines examined and that curcumin, a chemopreventive agent, down-regulated NF-κB in all cell lines as indicated by electrophoretic mobility gel shift assay and prevented the nuclear retention of p65 as shown by immunocytochemistry. All MM cell lines showed consitutively active IκB kinase (IKK) and IκBα phosphorylation. Curcumin suppressed the constitutive IκBα phosphorylation through the inhibition of IKK activity. Curcumin also down-regulated the expression of NF-κB–regulated gene products, including IκBα, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, cyclin D1, and interleukin-6. This led to the suppression of proliferation and arrest of cells at the G1/S phase of the cell cycle. Suppression of NF-κB complex by IKKγ/NF-κB essential modulator-binding domain peptide also suppressed the proliferation of MM cells. Curcumin also activated caspase-7 and caspase-9 and induced polyadenosine-5′-diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) cleavage. Curcumin-induced down-regulation of NF-κB, a factor that has been implicated in chemoresistance, also induced chemosensitivity to vincristine and melphalan. Overall, our results indicate that curcumin down-regulates NF-κB in human MM cells, leading to the suppression of proliferation and induction of apoptosis, thus providing the molecular basis for the treatment of MM patients with this pharmacologically safe agent.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a B-cell malignancy characterized by the latent accumulation in bone marrow of secretory plasma cells with a low proliferative index and an extended life span.1 MM accounts for 1% of all cancers and more than 10% of all hematologic cancers. Various agents used for the treatment of myeloma include combinations of vincristine, Bis-2-chloroethylnitrosourea (BCNU), melphalan, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, and prednisone or dexamethasone.2 Usually, patients younger than 65 years are treated with high-dose melphalan with autologous stem-cell support, and older patients who cannot tolerate such intensive treatment receive standard-dose oral melphalan and prednisone. Despite these treatments, this malignancy remains incurable, with a complete remission rate of 5% and a median survival of 30 to 36 months.3 4

The dysregulation of the apoptotic mechanism in plasma cells is considered a major underlying factor in the pathogenesis and subsequent chemoresistance in MM. It is established that interleukin-6 (IL-6), produced in either an autocrine or a paracrine manner, has an essential role in the malignant progression of MM by regulating the growth and survival of tumor cells.5,6 The presence of IL-6 leads to constitutive activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription–3 (Stat3), which in turn results in expression of high levels of the antiapoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma–xL (Bcl-xL).7Bcl-2 overexpression, another important characteristic of the majority of MM cell lines,8 rescues these tumor cells from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis.4 Furthermore, treatment of MM cells with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) activates nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB), induces secretion of IL-6, induces expression of various adhesion molecules, and promotes proliferation.9 Besides, MM cells have been shown to express the ligand for the receptor that activates NF-κB (receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand [RANKL]), a member of the TNF superfamily, which could mediate MM-induced osteolytic bone disease.10-12

One of the potential mechanisms by which MM cells could develop resistance to apoptosis is through the activation of nuclear transcription factor NF-κB.13,14 Under normal conditions, NF-κB is present in the cytoplasm as an inactive heterotrimer consisting of p50, p65, and IκBα subunits. On activation, IκBα undergoes phosphorylation and ubiquitination-dependent degradation by the 26S proteosome, thus exposing nuclear localization signals on the p50-p65 hetrodimer, leading to nuclear translocation and binding to a specific consensus sequence in the DNA (5′-GGGACTTTC-3′). The binding activates gene expression, which in turn results in gene transcription.15The phosphorylation of IκBα occurs through the activation of IκB kinase (IKK).16 The IKK complex consists of 3 proteins: IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ/NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO).16 IKKα and IKKβ are the kinases that are capable of phosphorylating IκBα, whereas IKKγ/NEMO is a scaffold protein that is critical for the IKKα and IKKβ activity. Extensive research during the past few years has indicated that NF-κB regulates the expression of various genes that play critical roles in apoptosis, tumorigenesis, and inflammation.17 Some of the NF-κB–regulated genes include IκBα, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, bcl-xL, cyclo-oxegenase–2 (COX-2), IL-6, and the adhesion molecules intercellular adhesion molecule–1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule–1 (VCAM-1), and endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule–1 (ELAM-1). Recently, it was reported that NF-κB is constitutively active in MM cells, leading to bcl-2 expression, which rescues these cells from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis.4,18 Because MM cells express IL-6, various adhesion molecules, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2,4-6,8,19which are all regulated by NF-κB,17 and because their suppression can lead to apoptosis, we propose that NF-κB is an important target for MM treatment.

To identify a pharmacologically safe and effective agent with which to block constitutive NF-κB in MM, we selected curcumin (diferuloylmethane). We can cite the following reasons: (1) Curcumin has been shown by us and others to suppress NF-κB activation induced by various inflammatory stimuli.20,21 (2) Curcumin inhibits the activation of IKK activity needed for NF-κB activation.22-24 (3) Curcumin has been shown to down-regulate the expression of various NF-κB–regulated genes, including bcl-2, COX2, matrix metalloproteinase–9 (MMP-9), TNF, cyclin D1, and the adhesion molecules.20-27 (4) Curcumin has been reported to induce apoptosis in a wide variety of cells through sequential activation of caspase-8, beta-interaction domain (BID) cleavage, cytochrome-C release, caspase-9, and caspase-3.28-30 (5) Numerous studies in animals have demonstrated that curcumin has potent chemopreventive activity against a wide variety of different tumors.31,32 (6) Administration of curcumin in humans, even at 8 g per day in phase 1 clinical trials, has been shown to be quite safe.33

Our results demonstrate that all MM cell lines expressed constitutively active NF-κB, which was suppressed by curcumin through inhibition of IKK activity. This led to down-regulation of expression of gene products regulated by NF-κB, thus suppressing proliferation and inducing apoptosis in MM cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Human MM cell lines U266, RPMI 8226, and MM.1 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD). Cell lines U266 (ATCC no. TIB-196) and RPMI 8226 (ATCC no. CCL-155) are plasmacytomas of B-cell origin. U266 is known to produce monoclonal antibodies and IL-6.5,34 RPMI 8226 produces only immunoglobulin light chains, and there is no evidence for heavy chain or IL-6 production. The MM.1 (also called MM.1S) cell line, established from the peripheral blood cells of a patient with immunoglobulin A (IgA) myeloma, secretes lambda light chain, is negative for the presence of EBV gene, and expresses leukocyte antigen human lymphocyte antigen (HLA)–DR, proliferation cell antigen (PCA-1), and T9 and T10 antigens.35 MM.1R is a dexamethasone-resistant variant of MM.1 cells36 and was kindly provided by Dr Steve T. Rosen of Northwestern University Medical School (Chicago, IL).

The rabbit polyclonal antibodies to IκBα, p50, p65, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, polyadenosine-5′-diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP), and annexin V kit were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (CA). Antibodies against cleaved PARP, phospho-IκBα, procaspase-7, and procaspase-9 and the polynucleotide kinase kit were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Anti-IKKα and anti-IKKβ antibody ware kindly provided by Imgenex (San Diego, CA). Goat antirabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA); goat antimouse HRP was purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY); and goat antirabbit Alexa 594 was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Cell-permeable NEMO– binding domain (NBD) peptide NH2-DRQIKIWFQNRRMKWKKTALDWSWLQTE-CONH2, and the control peptide NEMO-C (NH2-DRQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK-CONH2) were kind gifts from Imgenex. Curcumin, vincristine, melphalan, caspase inhibitors (N-Acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-CHO [Ac-DEVD-CHO] or N-Acetyl-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-CHO [Ac-YVAD-CHO]), Hoechst 33342, and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St Louis, MO). Curcumin was prepared as a 20-mM solution in dimethyl sulfoxide and then further diluted in cell culture medium. RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.4% trypan blue vital stain, and antibiotic-antimycotic mixture were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Protein A/G–sepharose beads were obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL); γ-P32–adenosine triphosphate (γ-P32–ATP) was from ICN Pharmaceuticals (Costa Mesa, CA). A human IL-6 kit was purchased from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA). Apo Logix carboxyfluorescein caspase detection kit was a gift from Cell Technology (Minneapolis, MN).

Cell culture

All the human multiple myeloma cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1 × antibiotic-antimycotic. U266, MM.1, and MM.1R were cultured in 10% FBS, whereas cell line RPMI 8226 was grown in 20% FBS.34-37 Occasionally cells were tested by Hoechst staining and by custom polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for mycoplasma contamination.

Preparation of nuclear extracts for NF-κB

The nuclear extracts were prepared according to Schreiber et al.38 Briefly, 2 × 106 cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and suspended in 0.4 mL hypotonic lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors for 30 minutes. The cells were then lysed with 12.5 μL 10% Nonidet P-40. The homogenate was centrifuged, and supernatant containing the cytoplasmic extracts was stored frozen at −80°C. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 25 μL ice-cold nuclear extraction buffer. After 30 minutes of intermittent mixing, the extract was centrifuged, and supernatants containing nuclear extracts were secured. The protein content was measured by the Bradford method. If the nuclear extracts were not used immediately, they were stored at −80°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay for NF-κB

NF-κB activation was analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as described previously.39 In brief, 8 μg nuclear extracts prepared from curcumin-treated or untreated cells were incubated with 32P end-labeled 45-mer double-stranded NF-κB oligonucleotide from human immunodeficiency virus–1 long terminal repeat (5′-TTGTTACAAGGGACTTTCCGCT GGGGACTTTCCAG GGAGGCGTGG-3′; underlining indicates NF-κB binding site) for 15 minutes at 37°C, and the DNA-protein complex was resolved in a 6.6% native polyacrylamide gel. The radioactive bands from the dried gels were visualized and quantitated by the PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) with the use of ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Immunocytochemistry for NF-κB p65 localization

Curcumin-treated MM cells were plated on a glass slide by centrifugation with the use of a Cytospin 4 (Thermoshendon, Pittsburgh, PA), air dried for 1 hour at room temperature, and fixed with cold acetone. After a brief washing in PBS, slides were blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 1 hour and then incubated with rabbit polyclonal antihuman p65 antibody (dilution, 1:100). After overnight incubation, the slides were washed and then incubated with goat antirabbit IgG–Alexa 594 (1:100) for 1 hour and counterstained for nuclei with Hoechst (50 ng/mL) for 5 minutes. Stained slides were mounted with mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals) and analyzed under an epifluorescence microscope (Labophot-2; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Pictures were captured by means of Photometrics Coolsnap CF color camera (Nikon, Lewisville, TX) and MetaMorph version 4.6.5 software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown PA).

Western blot

First, 30 to 50 μg cytoplasmic protein extracts, prepared as described,40 were resolved on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel. After electrophoresis, the proteins were electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% nonfat milk, and probed with antibodies against either IκBα, phospho-IκBα, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or cyclin D1 (1:3000) for 1 hour. Thereafter, the blot was washed, exposed to HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour, and finally detected by chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Arlington Heights, IL).

For detection of cleavage products of PARP, whole-cell extracts were prepared by lysing the curcumin-treated cells in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane chloride], pH 7.4; 250 mM NaCl; 2 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], pH 8.0; 0.1% Triton-X100; 0.01 mg/mL aprotinin; 0.005 mg/mL leupeptin; 0.4 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]; and 4 mM NaVO4). Lysates were then spun at 14 000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove insoluble material. Lysates were resolved on 7.5% gel and probed with PARP antibodies. PARP was cleaved from the 116-kDa intact protein into 85-kDa and 40-kDa peptide products. To detect cleavage products of procaspase-7 and procaspase-9, whole-cell extracts were resolved on 10% gel and probed with appropriate antibodies.

IκB kinase assay

The IκB kinase assay was performed by a modified method as described earlier.41 Briefly, 200 μg cytoplasmic extracts were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg anti-IKKα and anti-IKKβ antibodies each, and the immune complexes so formed were precipitated with 0.01 mL protein A/G–sepharose beads for 2 hours. The beads were washed first with lysis buffer and then with the kinase assay buffer (50 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid] pH 7.4, 20 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)). The immune complex was then assayed for the kinase activity with the use of kinase assay buffer containing 20 μCi (0.74 MBq)] γ-P32–ATP, 10 μM unlabeled ATP, and 2 μg glutathione S-transferase–IκBα per sample (1-54). After incubation at 30°C for 30 minutes, the reaction was stopped by boiling the solution in 6 × SDS sample buffer. Then, the reaction mixture was resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE. The radioactive bands of the dried gel were visualized and quantitated by PhosphorImager. To determine the total amount of IKK complex in each sample, 60 μg cytoplasmic protein was resolved on a 7.5% acrylamide gel and then electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane; the membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk protein for 1 hour and then incubated with either anti-IKKα or anti-IKKβ antibodies for 1 hour. The membrane was then washed and treated with HRP-conjugated secondary antimouse IgG antibody and finally detected by chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

MTT assay

The antiproliferative effects of curcumin against different MM cell lines were determined by the MTT dye uptake method as described earlier.42 Briefly, the cells (5000 per well) were incubated in triplicate in a 96-well plate in the presence or absence of indicated test samples in a final volume of 0.1 mL for 24 hours at 37°C. Thereafter, 0.025 mL MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well. After a 2-hour incubation at 37°C, 0.1 mL extraction buffer (20% SDS, 50% dimethylformamide) was added; incubation was continued overnight at 37°C; and then the optical density (OD) at 590 nm was measured by means of a 96-well multiscanner autoreader (Dynatech MR 5000, Chantilly, VA), with the extraction buffer as blank. The following formula was used: Percentage cell viability = (OD of the experiment samples/OD of the control) × 100.

Thymidine incorporation assay

The antiproliferative effects of curcumin were also monitored by the thymidine incorporation method. For this, 5000 cells in 100 μL medium were cultured in triplicate in 96-well plates in the presence or absence of curcumin for 24 hours. At 6 hours before the completion of experiment, cells were pulsed with 0.5 μCi (0.0185 MBq)3H-thymidine, and the uptake of 3H-thymidine was monitored by means of a Matrix-9600 β-counter (Packard Instruments, Downers Grove, IL).

Flow cytometric analysis

To determine the effect of curcumin on the cell cycle, MM cells were treated for different times, washed, and fixed with 70% ethanol. After incubation overnight at −20°C, cells were washed with PBS prior to staining with propidium iodide (PI), and then suspended in staining buffer (10 μg/mL PI; 0.5% Tween-20; 0.1% RNase in PBS). The cells were analyzed by means of a fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) Vantage flow cytometer that uses the CellQuest acquisition and analysis programs (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Cells were gated to exclude cell debris, cell doublets, and cell clumps.

To determine the apoptosis, curcumin-treated cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, resuspended in 100 μL binding buffer containing fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry. As curcumin also emits the fluorescence in the same range as FITC, unstained treated cells were also analyzed in parallel.

Determination of IL-6 protein

Cell-free supernatants were collected from untreated or curcumin-treated cultures of multiple myeloma cells. Aliquots of 100 μL were removed, and IL-6 contents were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (BioSource International).

Results

Human MM U266, RPMI 8226, MM.1, and MM.1R cell lines used in our study are well characterized.34-37 We used them to investigate the effect of curcumin on constitutively active NF-κB, NF-κB–regulated gene expression, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. The timing and dose of curcumin used to down-regulate NF-κB had no effect on cell viability.

Curcumin suppresses constitutive NF-κB expressed by multiple myeloma cells

We first investigated the NF-κB status in 4 different MM cell lines by EMSA. The results shown in Figure1 indicate that all 4 cell lines expressed constitutively active NF-κB, resolved as an upper and a lower band. We then investigated the effect of curcumin on constitutively active NF-κB. We first examined the dose of curcumin required for complete suppression of NF-κB. For this, all the MM cell lines were treated with different concentrations of curcumin for 4 hours and then examined for NF-κB by EMSA. Densitometric analysis of the retarded radiolabeled probe showed a decrease in NF-κB DNA-binding activity. These results showed that 50 μM curcumin was sufficient to fully suppress the constitutive NF-κB activation in U266 (Figure 1A), MM.1 (Figure 1B), MM.1R (Figure 1C), and RPMI 8226 (Figure 1D). We then examined the minimum duration of exposure to curcumin required for suppression of NF-κB. For this, cells were incubated with 50 μM curcumin for different periods of time, and the nuclear extracts were prepared and examined for NF-κB by EMSA. The results showed that curcumin down-regulated constitutive NF-κB in all 4 cell lines but with different kinetics. Complete down-regulation of NF-κB occurred at 4 hours in U266 (Figure1E), MM.1 (Figure 1F), and MM.1R (Figure 1G) cells, whereas it took 8 hours to down-regulate NF-κB in RPMI 8226 cells (Figure 1H). Curcumin down-regulated only the upper band and not the lower band of NF-κB in most cases. In the case of RPMI 8226 cells, both bands were down-regulated.

Effect of curcumin on constitutive nuclear NF-κB in multiple myeloma cells.

Curcumin inhibits constitutive nuclear NF-κB in multiple myeloma cells. (A-D) Dose responses of NF-κB to curcumin treatment in U266 (panel A), MM.1 (panel B), MM1R (panel C), and RPMI 8226 (panel D) cells. First, 2 × 106 cells per milliliter were treated with the indicated concentration of curcumin for 4 hours and tested for nuclear NF-κB by EMSA as described. (E-I) The effect of exposure duration on curcumin-induced NF-κB suppression in U266 (panel E), MM.1 (panel F), MM.1R (panel G), and RPMI 8226 (panel H) cells. Cells were treated with curcumin (50 μM) for the indicated times and tested for nuclear NF-κB by EMSA as described. The binding of NF-κB to the DNA is specific and consists of p50 and p65 subunits (panel I). Nuclear extracts were prepared from U266 cells (2 × 106/mL), incubated for 30 minutes with different antibodies or unlabeled NF-κB oligonucleotide probe, and then assayed for NF-κB by EMSA.

Effect of curcumin on constitutive nuclear NF-κB in multiple myeloma cells.

Curcumin inhibits constitutive nuclear NF-κB in multiple myeloma cells. (A-D) Dose responses of NF-κB to curcumin treatment in U266 (panel A), MM.1 (panel B), MM1R (panel C), and RPMI 8226 (panel D) cells. First, 2 × 106 cells per milliliter were treated with the indicated concentration of curcumin for 4 hours and tested for nuclear NF-κB by EMSA as described. (E-I) The effect of exposure duration on curcumin-induced NF-κB suppression in U266 (panel E), MM.1 (panel F), MM.1R (panel G), and RPMI 8226 (panel H) cells. Cells were treated with curcumin (50 μM) for the indicated times and tested for nuclear NF-κB by EMSA as described. The binding of NF-κB to the DNA is specific and consists of p50 and p65 subunits (panel I). Nuclear extracts were prepared from U266 cells (2 × 106/mL), incubated for 30 minutes with different antibodies or unlabeled NF-κB oligonucleotide probe, and then assayed for NF-κB by EMSA.

Because NF-κB is a family of proteins, various combinations of Rel/NF-κB protein can constitute an active NF-κB heterodimer that binds to a specific sequence in DNA.15 To show that the retarded band visualized by EMSA in MM cells was indeed NF-κB, we incubated nuclear extracts from MM cells with antibody to either the p50 (NF-κB1) or the p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-κB. Both shifted the band to a higher molecular mass (Figure 1I), thus suggesting that the major NF-κB band in MM cells consisted of p50 and p65 subunits. A nonspecific minor band was observed in some MM cell lines; this was not supershifted by the antibody. Neither preimmune serum nor the irrelevant antibody as anti–cyclin D1 had any effect. Excess unlabeled NF-κB (100-fold), but not the mutated oligonucleotides, caused complete disappearance of the band.

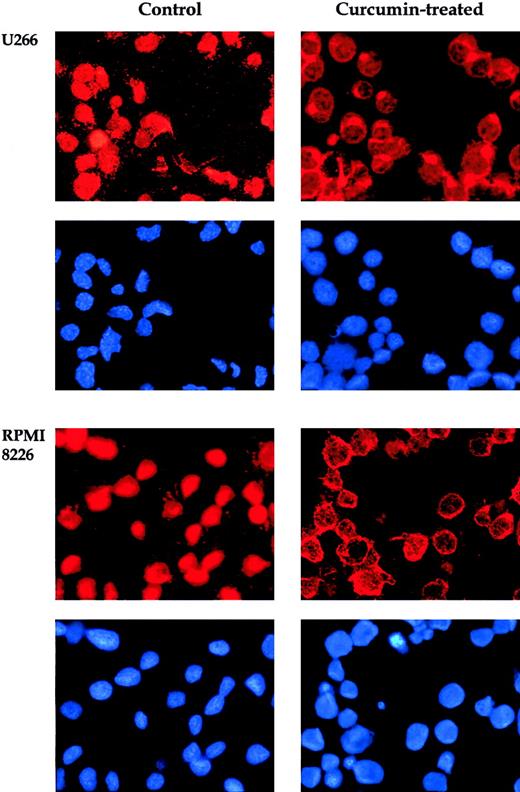

When NF-κB is activated, the p65 subunit of the NF-κB–containing transactivation domain is translocated to the nucleus.15In the inactive state, the p65 subunit of NF-κB is retained in the cytoplasm. To confirm that curcumin suppresses nuclear retention of p65, we used immunocytochemistry. Curcumin-treated and untreated cells were cytospun on a glass slide, immunostained with antibody p65, and then visualized by the Alexa-594–conjugated second antibody as described in “Materials and methods.” The results in Figure2 clearly demonstrate that curcumin prevented the translocation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB to the nucleus in all 4 MM cell lines. These cytologic findings were consistent with the NF-κB inhibition observed by means of EMSA.

Effect of curcumin on p65.

Curcumin induces redistribution of p65. U266 and RPMI 8226 cells were incubated alone or with curcumin (50 μM) for 4 hours and then analyzed for the distribution of p65 by immunocytochemistry. Red stain indicates the localization of p65, and blue stain indicates nucleus. Original magnification, × 200).

Effect of curcumin on p65.

Curcumin induces redistribution of p65. U266 and RPMI 8226 cells were incubated alone or with curcumin (50 μM) for 4 hours and then analyzed for the distribution of p65 by immunocytochemistry. Red stain indicates the localization of p65, and blue stain indicates nucleus. Original magnification, × 200).

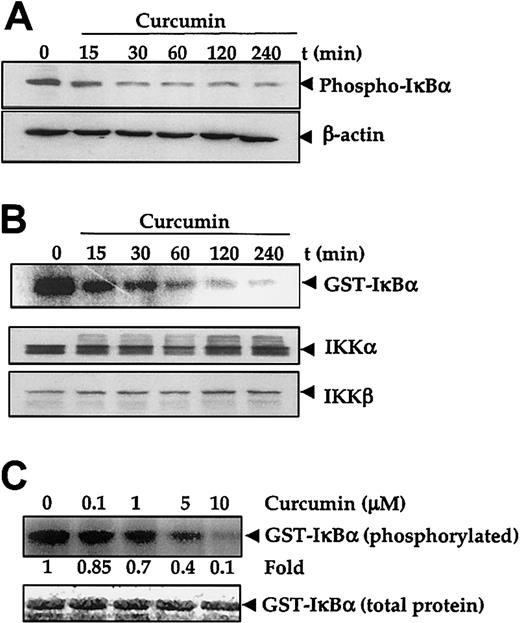

Curcumin inhibits IκBα phosphorylation and IκB kinase activity

The degradation of IκBα and subsequent release of NF-κB (p65 to p50) requires prior phosphorylation at Ser32 and Ser36 residues.43 Therefore, to investigate whether the inhibitory effect of curcumin is mediated through the alteration of phosphorylation of IκBα, U266 cells were treated with curcumin, and their protein extracts were checked for phospho-IκBα expression. Results in Figure 3A show that untreated U266 cells constitutively expressed Ser32-phosphorylated IκBα. Upon curcumin treatment, the phosphorylated IκBα content decreased rapidly.

Effect of curcumin on IκBα phosphorylation and IκB kinase.

Curcumin inhibits IκBα phosphoryalation and IκB kinase. (A-B) First, 5 × 106 U266 cells per 2.5 mL were treated with curcumin (50 μM) for the indicated times. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared for checking the level of phosphorylated IκBα by Western blotting (panel A), or IKK was immunoprecipitated and the kinase assay was performed (panel B) to check the IKK activity (upper panel), or Western blotting was performed for the analysis of total IKKα and IKKβ proteins in cytoplasmic extracts (lower panel). (C) Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from 5 × 106 U266 cells, IKK was immunoprecipitated, and kinase assay was performed in the absence or presence of the indicated concentration of curcumin (upper panel). Lower panel indicates the amount of glutathione S–transferase (GST)–IκBα protein stained with Coomassie blue in each well in the same dried gel.

Effect of curcumin on IκBα phosphorylation and IκB kinase.

Curcumin inhibits IκBα phosphoryalation and IκB kinase. (A-B) First, 5 × 106 U266 cells per 2.5 mL were treated with curcumin (50 μM) for the indicated times. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared for checking the level of phosphorylated IκBα by Western blotting (panel A), or IKK was immunoprecipitated and the kinase assay was performed (panel B) to check the IKK activity (upper panel), or Western blotting was performed for the analysis of total IKKα and IKKβ proteins in cytoplasmic extracts (lower panel). (C) Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from 5 × 106 U266 cells, IKK was immunoprecipitated, and kinase assay was performed in the absence or presence of the indicated concentration of curcumin (upper panel). Lower panel indicates the amount of glutathione S–transferase (GST)–IκBα protein stained with Coomassie blue in each well in the same dried gel.

Phosphorylation of IκBα is mediated through IKK.43 In vitro kinase assay using immunoprecipitated IKK from untreated U266 cells and the GST-IκBα as substrate showed constitutive IKK activity, whereas under similar conditions immunoprecipitated IKK from curcumin-treated cells showed a decreased kinase activity that corresponded to the duration of curcumin treatment (Figure 3B upper panel). However, immunoblotting analysis of the cell extracts of untreated and curcumin-treated cells showed no significant change in the protein levels of the IKK subunits IKKα and IKKβ in treated cells (Figure 3B middle and lower panels).

IKK has been shown to be regulated by several upstream kinases.43 44 Whether curcumin inhibited IKK activity directly or suppressed the activation of IKK was investigated. To determine if curcumin acted as a direct inhibitor of IKK activity, the IKK was immunoprecipitated from untreated U266 cells and then treated with different concentrations of curcumin for 30 minutes. After the treatment, the samples were examined for IKK activity with the use of GST-IκBα as a substrate. Results in Figure 3C (upper panel) showed that curcumin directly inhibited the IKK activity in a dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that curcumin is a direct inhibitor of IKK. Because we did not use purified IKK, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that curcumin suppressed an upstream kinase required for IKK activation.

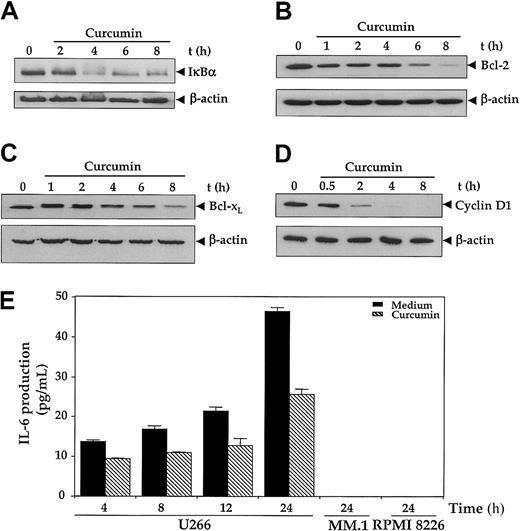

Curcumin down-regulates the expression of NF-κB–regulated gene products

Because IκBα, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and cyclin D1 have all been shown to be regulated by NF-κB,17we examined the effect of curcumin on the expression of these gene products by immunoblotting. As depicted in Figure4, all 4 gene products were expressed in U266 cells. The treatment of cells with curcumin down-regulated the pools of IκBα (Figure 4A), Bcl-2 (Figure 4B), Bcl-xL(Figure 4C), and cyclin D1 (Figure 4E) proteins in a time-dependent manner, although the kinetics of suppression followed by each protein were different. Cyclin D1 showed the most abrupt and complete depletion within 4 hours of curcumin. Bcl-2 also showed a complete decline, but it achieved the lowest level by 8 hours. On the other hand, IκBα and Bcl-xL showed only a partial decline.

Effect of curcumin on NF-κB–regulated gene products.

First, 2 × 106 U266 cells were treated with curcumin (50 μM) for the indicated times, and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared. (A-D) Then, 60 μg cytoplasmic extracts were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gel, electrotransferred on a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed for the following: IκBα (panel A); Bcl-2 (panel B); Bcl-xL (panel C); and cyclin D1 (panel D). The same blots were stripped and reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody to show equal protein loading (lower panels). (E) Curcumin down-regulates IL-6 production. U266, MM.1, or RPMI 8226 cells (2 × 106/mL) were treated with curcumin (10 μM); supernatants were harvested after 24 hours, and levels of IL-6 were assayed by IL-6 ELISA kit as described in “Materials and methods.” Values are mean IL-6 levels (error bars indicate standard deviations SDs) obtained from 3 independent treatments of cell with curcumin.

Effect of curcumin on NF-κB–regulated gene products.

First, 2 × 106 U266 cells were treated with curcumin (50 μM) for the indicated times, and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared. (A-D) Then, 60 μg cytoplasmic extracts were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gel, electrotransferred on a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed for the following: IκBα (panel A); Bcl-2 (panel B); Bcl-xL (panel C); and cyclin D1 (panel D). The same blots were stripped and reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody to show equal protein loading (lower panels). (E) Curcumin down-regulates IL-6 production. U266, MM.1, or RPMI 8226 cells (2 × 106/mL) were treated with curcumin (10 μM); supernatants were harvested after 24 hours, and levels of IL-6 were assayed by IL-6 ELISA kit as described in “Materials and methods.” Values are mean IL-6 levels (error bars indicate standard deviations SDs) obtained from 3 independent treatments of cell with curcumin.

Interleukin-6 is another NF-κB–regulated gene17 and has been shown to serve as a growth factor for MM cells.5-7 As shown in Figure 4E, U-266 cells produced a significant amount of IL-6 protein in a time-dependent manner whereas neither MM.1 nor RPMI 8226 produced any detectable amount of IL-6 as measured by the ELISA method. Curcumin treatment inhibited the production of IL-6 by U266 cells.

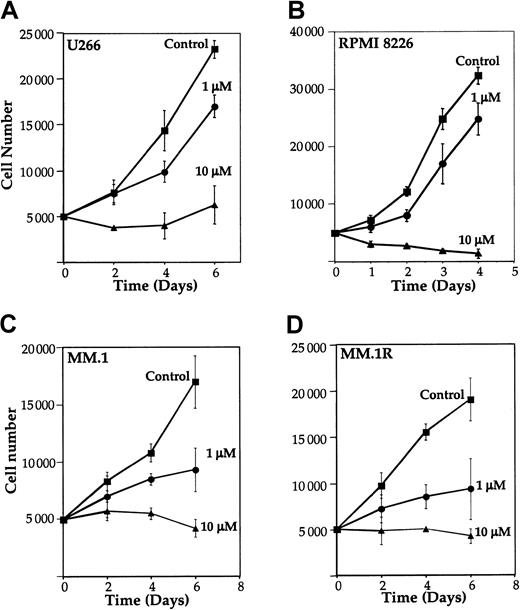

Curcumin suppresses the proliferation of MM cells

Because NF-κB has been implicated in cell survival and proliferation,13 14 we examined the effect of curcumin on proliferation of MM cell lines. U266, RPMI 8226, MM.1, and MM.1R cells were cultured in the presence of different concentrations of curcumin, and the number of viable cells examined by trypan blue dye-exclusion method. Results in Figure 5 show that curcumin at a concentration as low as 1 μM inhibited growth by 27%, 23%, 45%, and 51% in U266 (Figure 5A), RPMI 8226 (Figure 5B), MM.1 (Figure 5C), and MM.1R (Figure 5D), respectively. At 10 μM, curcumin completely suppressed the growth in all cell lines. These results indicate that curcumin suppresses the proliferation of all MM cell lines tested, including MM.1R (the line resistant to dexamethasone-induced apoptosis).

Effect of curcumin on the growth of human multiple myeloma cells.

Curcumin inhibits the growth of human multiple myeloma cells. U266 (panel A), RPMI 8226 cells (panel B), MM.1 (panel C), or MM.1R (panel D) (5000 cells per 0.1 mL) were incubated at 37°C with curcumin (1 μM and 10 μM) for the indicated time, and the viable cells were counted by means of the standard trypan blue dye-exclusion test. The results are shown as the means (± SDs) cell count from triplicate cultures.

Effect of curcumin on the growth of human multiple myeloma cells.

Curcumin inhibits the growth of human multiple myeloma cells. U266 (panel A), RPMI 8226 cells (panel B), MM.1 (panel C), or MM.1R (panel D) (5000 cells per 0.1 mL) were incubated at 37°C with curcumin (1 μM and 10 μM) for the indicated time, and the viable cells were counted by means of the standard trypan blue dye-exclusion test. The results are shown as the means (± SDs) cell count from triplicate cultures.

We also examined the antiproliferative effects of curcumin by thymidine incorporation in U266 cells. Curcumin suppressed thymidine incorporation within 24 hours in a dose-dependent manner (Figure6A). The MTT method (which indicates the mitochondrial activity of the cells) showed that curcumin suppressed the mitochondrial activity of U266 cells within 24 hours, and the suppression occurred in a dose-dependent manner (Figure6B).

Effect of curcumin on growth and apopotosis in human multiple myeloma cells.

Curcumin inhibits the growth of human multiple myeloma cells and induces apoptosis. (A) U266 cells (5000/0.1 mL) were incubated with different concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours, and cell proliferation assay was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are shown as means (± SDs) percentage of [3H]-thymidine incorporation of triplicate cultures compared with the untreated control. (B) U266 cells (5000/0.1 mL) were incubated with different concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours, and cell viability was determined by the MTT method, as described in “Materials and methods.” The results are shown as the means (± SDs) percentage viability from triplicate cultures. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of annexin V–FITC–stained cells after treatment with different concentrations of curcumin. U266 cells were incubated alone or with the indicated concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours; thereafter, cells were either left unstained (left panels) or stained with annexin V–FITC (right panels). Unstained cells exhibited autofluorescence because of curcumin.

Effect of curcumin on growth and apopotosis in human multiple myeloma cells.

Curcumin inhibits the growth of human multiple myeloma cells and induces apoptosis. (A) U266 cells (5000/0.1 mL) were incubated with different concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours, and cell proliferation assay was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are shown as means (± SDs) percentage of [3H]-thymidine incorporation of triplicate cultures compared with the untreated control. (B) U266 cells (5000/0.1 mL) were incubated with different concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours, and cell viability was determined by the MTT method, as described in “Materials and methods.” The results are shown as the means (± SDs) percentage viability from triplicate cultures. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of annexin V–FITC–stained cells after treatment with different concentrations of curcumin. U266 cells were incubated alone or with the indicated concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours; thereafter, cells were either left unstained (left panels) or stained with annexin V–FITC (right panels). Unstained cells exhibited autofluorescence because of curcumin.

Curcumin induces apoptosis in MM cells

We investigated whether suppression of NF-κB in MM cells also leads to apoptosis. The curcumin-induced apoptosis was examined by the annexin V method. Annexin V binds to those cells that express phosphatidylserine on the outer layer of the cell membrane, a characteristic feature of cells entering apoptosis. This allows for live cells (unstained with either fluorochrome) to be discriminated from apoptotic cells (stained only with annexin V).45 To check this, U266 cells were treated for 24 hours with different concentrations of curcumin and then stained with annexin V–FITC. Results in Figure 6C show a dose-dependent increase in cells positive for annexin V, indicating the onset of apoptosis in curcumin-treated cells.

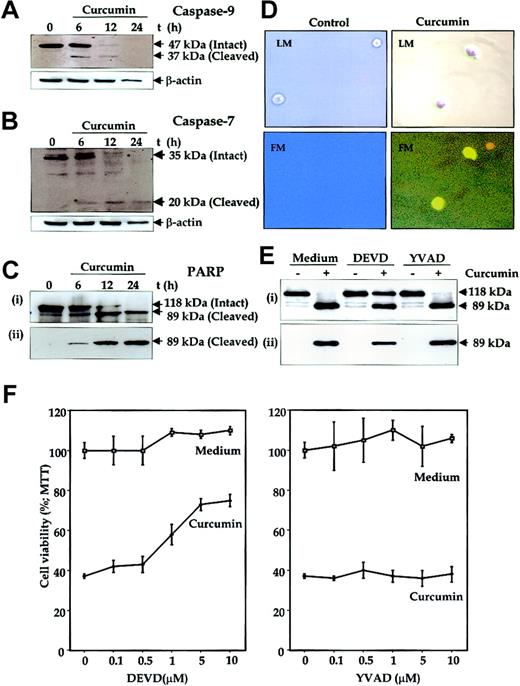

Another hallmark of apoptosis is activation of caspases. To determine this, U266 cells were treated with curcumin for different periods of time, and whole-cell extracts were prepared and analyzed for activation of caspase-9 (an upstream caspase) and caspase-7 (a downstream caspase) and for cleavage of PARP, a well-known substrate for caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7.46 Immunoblot analysis of the extracts from cells treated with curcumin for different times clearly showed a time-dependent activation of caspase-9 (Figure7A), as indicated by the disappearance of a 47-kDa band and the appearance of a 37-kDa band. Similarily, the Western blot analysis also showed an activation of caspase-7 (Figure7B), as indicated by the disappearance of a 35-kDa band and the appearance of a 20-kDa band. Activation of downstream caspases led to the cleavage of a 118-kDa PARP protein into an 89-kDa fragment, another hallmark of cells undergoing apoptosis (Figure 7C), whereas untreated cells did not show any PARP cleavage. Antibodies that recognize only the cleaved 89-kDa PARP species increased with an increase in duration of curcumin treatment (Figure 7C lower panel). These results clearly suggest that curcumin induced apoptosis in MM cells.

Mediation of curcumin-induced apoptosis of human multiple myeloma cells through caspase activation.

(A-C) U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were incubated in the absence or presence of curcumin (50 μM) for the indicated times. The cells were washed, and total proteins were extracted by lysing the cells. Then, 60 μg extracts were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gel, electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with anti–caspase-9 (panel A); anti–caspase-7 (panel B); anti-PARP (panel Ci); and anti–cleaved PARP (panel Cii) antibodies as described in “Materials and methods.” (D) Detection of caspase activation by fluorescence microscopy. Untreated or curcumin-treated U266 cells (12 hours) were examined for caspase activation by Apo Logix carboxyfluorescein caspase detection kit. Cells were analyzed under light microscopy (LM) and by fluorescence microscopy (FM). Green fluorescence indicates activated caspases. Original magnification, × 200. (E) Suppression of curcumin-induced PARP cleavage by caspase-3 inhibitor. U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were preincubated with caspase inhibitors Ac-DEVD-CHO (10 μM) or Ac-YVAD-CHO (10 μM) for 2 hours and then treated with curcumin (50 μM) for 24 hours. Thereafter, cell extracts were prepared and analyzed for PARP cleavage by using either anti-PARP antibody (i) or antibodies that recognize only cleaved PARP (ii) as described in “Materials and methods.” (F) Caspase-3 inhibitor protects cells from curcumin-induced cytotoxicity. U266 cells (5000/0.1 mL) were incubated with different concentrations of caspase inhibitors Ac-DEVD-CHO or Ac-YVAD-CHO for 2 hours and then treated with curcumin. After 24 hours, cell viability was determined by the MTT method, as described in “Materials and methods.” The results are shown as the means (± SDs) percentage viability from triplicate cultures.

Mediation of curcumin-induced apoptosis of human multiple myeloma cells through caspase activation.

(A-C) U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were incubated in the absence or presence of curcumin (50 μM) for the indicated times. The cells were washed, and total proteins were extracted by lysing the cells. Then, 60 μg extracts were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gel, electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with anti–caspase-9 (panel A); anti–caspase-7 (panel B); anti-PARP (panel Ci); and anti–cleaved PARP (panel Cii) antibodies as described in “Materials and methods.” (D) Detection of caspase activation by fluorescence microscopy. Untreated or curcumin-treated U266 cells (12 hours) were examined for caspase activation by Apo Logix carboxyfluorescein caspase detection kit. Cells were analyzed under light microscopy (LM) and by fluorescence microscopy (FM). Green fluorescence indicates activated caspases. Original magnification, × 200. (E) Suppression of curcumin-induced PARP cleavage by caspase-3 inhibitor. U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were preincubated with caspase inhibitors Ac-DEVD-CHO (10 μM) or Ac-YVAD-CHO (10 μM) for 2 hours and then treated with curcumin (50 μM) for 24 hours. Thereafter, cell extracts were prepared and analyzed for PARP cleavage by using either anti-PARP antibody (i) or antibodies that recognize only cleaved PARP (ii) as described in “Materials and methods.” (F) Caspase-3 inhibitor protects cells from curcumin-induced cytotoxicity. U266 cells (5000/0.1 mL) were incubated with different concentrations of caspase inhibitors Ac-DEVD-CHO or Ac-YVAD-CHO for 2 hours and then treated with curcumin. After 24 hours, cell viability was determined by the MTT method, as described in “Materials and methods.” The results are shown as the means (± SDs) percentage viability from triplicate cultures.

To further demonstrate the activation of caspases by curcumin in situ, we also labeled the cells with a cell-permeable carboxyfluorescein analog of benzyloxycarbonylalanylaspartic acid fluoromethyl ketone (zVAD-FMK; a general caspase inhibitor) that irreversibly binds to the activated caspases and gives a green fluorescence in the same range as FITC. Untreated cells did not show any fluorescence, but curcumin-treated cells showed an intense fluorescence, indicating the presence of active caspases in these cells (Figure 7D).

To determine whether caspase activation is needed for curcumin-induced PARP cleavage, U266 cells were treated with curcumin in the presence of caspase inhibitors Ac-DEVD-CHO (caspase-3 inhibitor) or Ac-YVAD-CHO (caspase-1 inhibitor) and analyzed for PARP cleavage. As shown in Figure 7E, caspase-3 inhibitor suppressed the curcumin-induced PARP cleavage whereas caspase-1 inhibitor did not.

To further determine whether caspase activation is needed for the suppression of cell growth induced by curcumin, U266 cells were treated with caspase inhibitors Ac-DEVD-CHO or Ac-YVAD-CHO and then examined for curcumin-induced cytotoxicity by the MTT method. Results shown in Figure 7F demonstrate a dose-dependent protection of cells from curcumin-induced cytotoxicity by caspase-3 inhibitor but not by caspase-1 inhibitor. These results, thus suggest that caspase-3 activation is essential for curcumin-induced cytotoxicity.

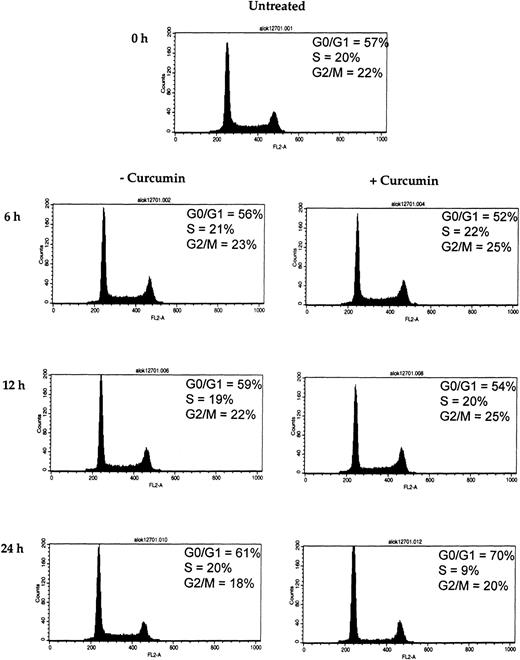

Curcumin arrests the cells at the G1/S phase of the cell cycle

D-type cyclins are required for the progression of cells from the G1 phase of the cell cycle to S phase (DNA synthesis).47 Because we observed a rapid decline of cyclin D1 in curcumin-treated MM cells, we wished to determine the effect of curcumin on U266 cell cycle. Flow cytometric analysis of the DNA from curcumin-treated cells showed a significant increase in the percentage of cells in the G1 phase, from 61% to 70%, and a decrease in the percentage of cells in the S phase, from 20% to 9%, within 24 hours of curcumin (10 μM) treatment (Figure8). These results clearly show that curcumin induces G1/S arrest of the cells.

Effect of curcumin on cells at G1/S phase of the cell cycle.

Curcumin arrests the cells at G1/S phase of the cell cycle. U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were incubated in the absence or presence of curcumin (10 μM) for the indicated times. Thereafter, the cells were washed, fixed, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed for DNA content by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.”

Effect of curcumin on cells at G1/S phase of the cell cycle.

Curcumin arrests the cells at G1/S phase of the cell cycle. U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were incubated in the absence or presence of curcumin (10 μM) for the indicated times. Thereafter, the cells were washed, fixed, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed for DNA content by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods.”

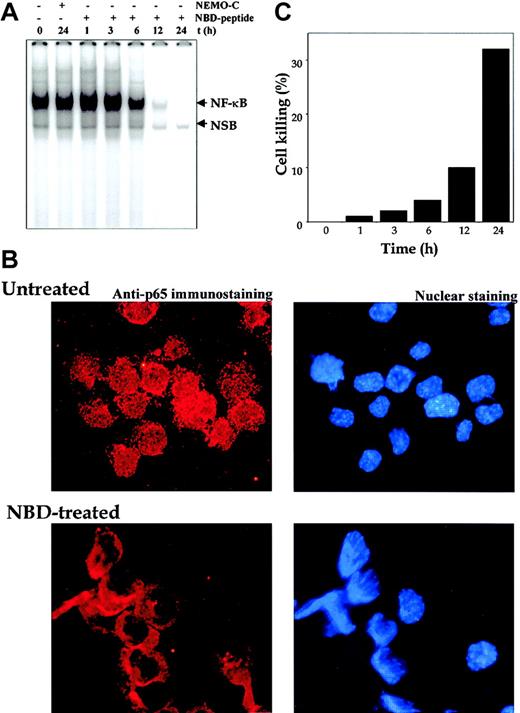

NEMO-binding domain (NBD) peptide suppresses constitutive NF-κB and proliferation of MM cells

IKK is composed of IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (also called NEMO). The amino-terminal α-helical region of NEMO has been shown to interact with the C-terminal segment of IKKα and IKKβ.16 A small peptide from the C-terminus of IKKα and IKKβ NEMO has been shown to block this interaction. To make it cell permeable, the NBD peptide was conjugated to a small sequence from the antennapedia homeodomain. This peptide has been shown to specifically suppress NF-κB activation. The peptide without the antennapedia homeodomain protein sequence was used as a control.

Our results to this point have shown that curcumin suppressed constitutive NF-κB, which in turn led to suppression of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis. To establish that NF-κB suppression is linked to proliferation and apoptosis, we used the NBD and control peptide. As shown in Figure9A, treatment of U266 cells with NEMO control peptide had no effect, whereas NBD peptide suppressed the constitutive NF-κB in a time-dependent manner, with complete suppression occurring at 12 hours. The suppression of NF-κB activation in MM cells was also independently confirmed by the immunocytochemistry. The results indicated a decrease in the nuclear pool of the p65 subunit of NF-κB (Figure 9B). Suppression of NF-κB by NBD peptide also led to inhibition of cell proliferation of U266 cells. Approximately 32% suppression of cell growth was observed after NBD treatment for 24 hours (Figure 9C). These results thus suggest that NF-κB suppression is indeed linked to the antiproliferative effects in MM cells.

Effect of NBD peptide on human multiple myeloma cells.

NEMO-binding domain (NBD) peptide inhibits constitutive NF-κB and induces cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma cells. (A) U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were treated with the indicated concentrations of NEMO control or NBD peptide (100 μM) for the indicated times. Nuclear extracts were checked for the presence of NF-κB DNA-binding activity by EMSA. (B) Untreated or NBD peptide–treated (100 μM; 12 hours) U266 cells were cytospun, and p65 immunocytochemistry was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Red stain indicates the localization of p65, and blue stain indicates nucleus. Original magnification, × 200). (C) U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were treated with the indicated concentrations of NEMO control or NBD peptide (100 μM) for the indicated times, and cell viability was monitored by the trypan blue dye-exclusion method. The percentage of cell killing was determined as follows: Percentage killing = (number of trypan blue stained cells/total cells) × 100.

Effect of NBD peptide on human multiple myeloma cells.

NEMO-binding domain (NBD) peptide inhibits constitutive NF-κB and induces cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma cells. (A) U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were treated with the indicated concentrations of NEMO control or NBD peptide (100 μM) for the indicated times. Nuclear extracts were checked for the presence of NF-κB DNA-binding activity by EMSA. (B) Untreated or NBD peptide–treated (100 μM; 12 hours) U266 cells were cytospun, and p65 immunocytochemistry was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Red stain indicates the localization of p65, and blue stain indicates nucleus. Original magnification, × 200). (C) U266 cells (2 × 106/mL) were treated with the indicated concentrations of NEMO control or NBD peptide (100 μM) for the indicated times, and cell viability was monitored by the trypan blue dye-exclusion method. The percentage of cell killing was determined as follows: Percentage killing = (number of trypan blue stained cells/total cells) × 100.

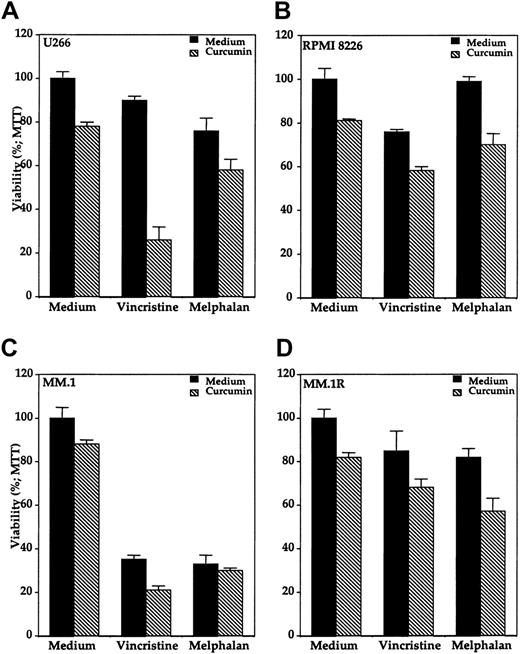

Curcumin potentiates the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents

Because NF-κB has been implicated in chemoresistance of cells, we investigated the effects of curcumin on chemosensitivity. We investigated the effect of curcumin on the cytotoxic effects of vincristine and melphalan against various multiple myeloma cell lines. These 2 chemotherapeutic agents showed variable cytotoxic effects in different multiple myeloma cell lines when treated alone (Figure10). MM.1 cells were clearly most sensitive to both the drugs (Figure 10C). The presence of curcumin enhanced the cytotoxic effects of both vincristine and melphalan against all the multiple myeloma cell lines. For instance, U266 cells were least sensitive to vincristine, but the presence of curcumin enhanced the cytotoxicity from below 10% to greater than 70% (Figure10A). When compared with MM.1 cells, dexamthasone-resistant MM.1R cells were also found to be relatively resistant to both vincristine as well as melphalan. The treatment of these chemoresistant cells with curcumin enhanced the cytotoxic effects of both the chemotherapeutic agents (Figure 10D). As a control, curcumin had minimal cytotoxic effect on normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells under these conditions (data not shown). These results indicate that curcumin may sensitize the multiple myeloma cells to the cytotoxic effects of vincristine and melphalan.

Effect of curcumin on cytotoxicity of vincristine and melphalan in human MM cells.

Curcumin potentiates the cytotoxic effect of vincristine and melphalan in human multiple myeloma cells. Multiple myeloma cells (10 000/0.1 mL), U266 (panel A), RPMI 8226 (panel B), MM.1 (panel C), and MM.1R (panel D) were incubated with either medium, vincristine (50 μM), or melphalan (10 μM) in the absence (black bars) or presence (hatched bars) of curcumin (10 μM) for 24 hours, and then the cell viability was determined by the MTT method as described. Values are means (± SDs) of triplicate cultures.

Effect of curcumin on cytotoxicity of vincristine and melphalan in human MM cells.

Curcumin potentiates the cytotoxic effect of vincristine and melphalan in human multiple myeloma cells. Multiple myeloma cells (10 000/0.1 mL), U266 (panel A), RPMI 8226 (panel B), MM.1 (panel C), and MM.1R (panel D) were incubated with either medium, vincristine (50 μM), or melphalan (10 μM) in the absence (black bars) or presence (hatched bars) of curcumin (10 μM) for 24 hours, and then the cell viability was determined by the MTT method as described. Values are means (± SDs) of triplicate cultures.

Discussion

Because of the central role of NF-κB in cell survival and proliferation, we explored this transcription factor as a target for the treatment of MM by using curcumin (diferuloylmethane). Our results indicate that NF-κB is constitutively active in all the human MM cell lines examined and that curcumin down-regulated the nuclear pool, or active form, of NF-κB and suppressed constitutive IκBα phosphorylation, IKK kinase activity, and expression of the NF-κB–regulated gene products IκBα, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, cyclin D1, and interleukin-6. This led to the suppression of proliferation, arrest of cells at the G1/S phase boundary of the cell cycle, and induction of apoptosis as indicated by the activation of caspase-7 and caspase-9 and PARP cleavage. Curcumin also induced chemosensitivity to vincristine and melphalan.

Our results indicate that all 4 MM cell lines (U266, RPMI 8226, MM.1, and MM.1R) expressed constitutively active NF-κB. These results are in agreement with 2 recent reports by Feinman et al4and Ni et al,18 who showed constitutive NF-κB in U266 and RPMI 8226 cells by EMSA. We now show that MM.1 and MM.1R, a dexamethasone-resistant cell line, also express constitutive NF-κB. Our results differ from those of Hideshima et al,48 who showed lack of constitutively active NF-κB in MM.1S (same as MM.1). Because the constitutive activation of NF-κB leads to nuclear translocation of p65, we confirmed the presence of nuclear p65 in all the cell lines by immunocytochemistry. Why do MM cells constitutively express NF-κB? Our results indicate that MM cells exhibit constitutively active IKK, the kinase required for NF-κB activation. This is the first report to show an elevated IKK activity in MM cells. Why these cells express an elevated IKK is, however, not clear at present.

We found that curcumin suppressed constitutive NF-κB activation in all 4 MM cell lines. These results are in agreement with previous reports from our laboratory and others that curcumin is a potent inhibitor of NF-κB activation.20-27 Curcumin inhibits NF-κB activation by blocking the constitutively active IKK present in MM cells. Because curcumin inhibited IKK activity both inside the cells and in vitro, we suggest that curcumin may be a direct inhibitor of IKK. Because we did not use recombinant enzyme, we cannot completely rule out the possibility of indirect inhibition of IKK by curcumin. In any case, curcumin appears to suppress IKK activation, which leads to inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation, as reported here, and thus abrogation of IκBα degradation. Our results are in agreement with previous reports that showed inhibition of IKK by curcumin in colon cancer cells and macrophages.22,24 A recent report showed that PS-1145, a rationally designed IKK inhibitor, blocked TNF-induced NF-κB activation in MM.1 cells.48 Because MM.1 cells in our study constitutively expressed NF-κB, no TNF induction was required. The concentration of curcumin required to block IKK activity in the cells was comparable to that reported for PS-1145.48

We found that suppression of NF-κB by curcumin down-regulated the expression of several gene products regulated by NF-κB. The expression of IκBα, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, IL-6, and cyclin D1,14,17,49 whose synthesis is known to be regulated by NF-κB, was suppressed by curcumin. We found that only U266 cells produced IL-6. Neither RPMI 8226 nor MM.1 produced any detectable IL-6. Previous reports on the production of IL-6 by these MM cell lines has been controversial.49-52

The suppression of cell proliferation by curcumin in MM cells is in agreement with our previous reports that curcumin-induced suppression of NF-κB leads to inhibition of cellular proliferation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma50 and acute myelogenous leukemia.51 Our results on the antiproliferative effects of curcumin are in agreement with those of Hideshima et al,48 who showed that PS-1145, an IKK blocker, inhibits cell proliferation. These workers reported that 50 μM PS-1145 inhibits the proliferation of the MM cell lines MM.1S, RPMI-8226, and U266 by less than 50%. In contrast, we found almost complete inhibition of proliferation of all these cell lines with as little as 10 μM curcumin.

Several potential mechanisms could explain why NF-κB down-regulation by curcumin leads to suppression of proliferation of MM cells. One of the potential mechanisms involves suppression of IL-6 production as shown in our studies. Numerous studies indicate that IL-6 is a potent growth factor for MM.5-7,52 Whether it is a paracrine or an autocrine growth factor for MM cells is highly controversial.6,52 In our studies it is unlikely, however, that curcumin suppressed the growth of MM cells through suppression of IL-6 production because 3 of the 4 cell lines examined produced no detectable IL-6. It is also unlikely that curcumin inhibits cell growth through down-regulation of the constitutively active Stat3 signaling because the proliferation of cells that do not express constitutively active Stat3 (eg, RPMI 8226) are also inhibited by curcumin.7 In our study, curcumin down-regulated expression of bcl-2 and bcl-xL, the proteins that have been implicated in the cell survival of MM cells.4 8Thus, it is possible that down-regulation of bcl-2 and bcl-xL by curcumin could lead to suppression of cell proliferation.

We also found that MM cells overexpress cyclin D1, another NF-κB–regulated gene, and that this expression is down-regulated by curcumin. The overexpression of cyclin D1 has been noted in a wide variety of tumors,53 but its role in MM cells has not been reported. Given that cyclin D1 is needed for cells to advance from the G1 to the S phase of the cell cycle, it is not surprising we found that curcumin induced G1/S arrest and thus caused suppression of cell proliferation.

Suppression of NF-κB by curcumin also led to apoptosis of MM cells, as indicated by activation of caspases and cleavage of PARP. These results are in agreement with reports indicating that NF-κB mediates antiapoptotic effects.13 18 Down-regulation of NF-κB also sensitized MM cells to vincristine and melphalan. Even the MM.1R cells, which have been shown to be resistant to dexamethasone, were sensitive to curcumin.

MM is an incurable, aggressive B-cell malignancy, and more than 90% of MM patients become chemoresistant. Several agents have been tested in the search for more effective treatment of MM. Besides curcumin, these include PS341 (a proteosome inhibitor) and thalidomide (an inhibitor of TNF production).54,55 Nonspecific drug toxicity is one of the major problems in drug development. Numerous studies have shown that curcumin is pharmacologically safe. It was recently demonstrated in phase 1 clinical trials that humans can tolerate up to 8 g curcumin per day when it is taken orally.33 Additionally, curcumin has been shown to down-regulate the expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and ELAM-1, all NF-κB–regulated gene products21 that have been implicated in activation of stromal cells by MM cells. TNF, another cytokine known to play a pathologic role in MM,9 has also been shown to be down-regulated by curcumin.27 The results presented here clearly demonstrate that curcumin can suppress NF-κB, IKK, bcl-2, bcl-xL, cyclin D1, and cell proliferation in MM cells. Our studies provide enough rationale for considering curcumin worthy of clinical trial in patients with multiple myeloma.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 5, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1320.

Supported by the Clayton Foundation for Research (B.B.A.) and by Leukemia-Lymphoma Society grant 6153-02 (N.D.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Bharat B. Aggarwal, Cytokine Research Section, Department of Bioimmunotherapy, Box 143, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: aggarwal@mdanderson.org.

![Fig. 6. Effect of curcumin on growth and apopotosis in human multiple myeloma cells. / Curcumin inhibits the growth of human multiple myeloma cells and induces apoptosis. (A) U266 cells (5000/0.1 mL) were incubated with different concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours, and cell proliferation assay was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are shown as means (± SDs) percentage of [3H]-thymidine incorporation of triplicate cultures compared with the untreated control. (B) U266 cells (5000/0.1 mL) were incubated with different concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours, and cell viability was determined by the MTT method, as described in “Materials and methods.” The results are shown as the means (± SDs) percentage viability from triplicate cultures. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of annexin V–FITC–stained cells after treatment with different concentrations of curcumin. U266 cells were incubated alone or with the indicated concentrations of curcumin for 24 hours; thereafter, cells were either left unstained (left panels) or stained with annexin V–FITC (right panels). Unstained cells exhibited autofluorescence because of curcumin.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/3/10.1182_blood-2002-05-1320/4/m_h80333772006.jpeg?Expires=1765987192&Signature=D1jl6aDozKdoQWpUcOeoNdgYMRYR8RMqJDLyiAYWuOMbCblfbQw7IfKbH4ekALUhv8JWDAq02krgCwTH~zNEL1Ql4F2l0vXzSdMrOYuxMJ-80BOJwhAjJdZsVbbFZvOzKBksCYQP9B1xQ~kn~49smTvcFslEezzCm9wghTgPLHYbkh68UaQDIGA-F2xtFfJ542v81OAy-b6WDvwad22Wh8r8jaaxDohVG~3VNIxlVFc4XdCaBfgaY4ImLREAkz~4Hnnv2UnrfNAylFz2tPCxY0YbEk-dHZAUhxSEPsIfEtwb2hBo-KAewz9t5t9kbA8qvndMZjCAuhVHXi485ZBNFQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal