Abstract

Despite the clinical success of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) in the treatment of lymphoma, there remains considerable uncertainty about its mechanism of action. Here we show that the ability of mAbs to translocate CD20 into low-density, detergent-insoluble membrane rafts appears to control how effectively they mediate complement lysis of lymphoma cells. In vitro studies using a panel of anti–B-cell mAbs revealed that the anti-CD20 mAbs, with one exception (B1), are unusually effective at recruiting human complement. Differences in complement recruitment could not be explained by the level of mAb binding or isotype but did correlate with the redistribution of CD20 in the cell membrane following mAb ligation. Membrane fractionation confirmed that B1, unlike 1F5 and rituximab, was unable to translocate CD20 into lipid rafts. In addition, we were able to drive B1 and a range of other anti–B-cell mAbs into a detergent-insoluble fraction of the cell by hyper–cross-linking with an F(ab′)2 anti-Ig Ab, a treatment that also conferred the ability to activate lytic complement. Thus, we have shown that an important mAb effector function appears to be controlled by movement of the target molecule into membrane rafts, either because a raft location favors complement activation by mAbs or because rafts are more sensitive to complement penetration.

Introduction

The success of the chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb), rituximab (Ritux), in treating B-cell malignancies and, more recently, autoimmune diseases has continued to focus attention on antibody effector mechanisms in order to explain how this mAb operates in vivo.1-4 What makes anti-CD20 mAbs so clinically effective is not clear, however, at least in vitro, they mediate both complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and, unlike many other anti–B-cell mAbs, are also able to mediate growth arrest and apoptosis in certain cell lines.5-9 At present, it is not known which of these mechanisms predominates in vivo or in fact whether anti-CD20 mAbs are able to use different effector mechanisms, according to where the target cells are located or their stage of differentiation. The most persuasive evidence supporting natural effector (ADCC and CDC) mechanisms in the therapeutic response comes from work in primates showing that an IgG4 variant of Ritux, unlike the clinically approved IgG1, was unable to deplete normal B cells.10 Since this IgG4 variant would be unable to recruit natural effectors effectively but should retain the binding and cross-linking functions needed for any direct cytotoxic activity, including the signaling of apoptosis, these data point toward CDC and ADCC as the major effectors in vivo. However, in vitro experiments show that signaling activity is often enhanced by hyper–cross-linking either using anti-Ig antisera or FcγR-bearing cells, such as ADCC effector cells, or with anti-CD20 mAb multimers.8,11 Thus, it is conceivable that switching the isotype of Ritux may have reduced transmembrane signaling by interfering with the hyper–cross-linking following FcγR-Fc interactions. The importance of FcγR in vivo also is supported by elegant work from Clynes et al12 using FcγR-deficient mice, which indicated that FcγR on macrophages are critical to the ability of mAbs to control subcutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Similarly, interesting clinical data now has revealed that non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patients expressing the high-affinity variant of FcγRIIIa (158V allotype) respond better to Ritux than those carrying the low-affinity 158F allotype.13 Thus, there is data to support a role for FcγR-bearing effectors in mediating the activity of anti-CD20 mAbs.

In contrast, understanding the role of complement in anti-CD20 therapy is more problematic, and while complement is consumed during Ritux treatment and appears to be responsible for much of the associated toxicity, its importance as an effector mechanism is still controversial.14-19 One of the main arguments against complement being a major effector is that the therapeutic activity of Ritux does not appear to correlate with the expression levels of the complement defense molecules CD55 or CD59.15Interestingly, however, a brief report of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients receiving Ritux showed that cells circulating 8 weeks after treatment did have increased CD59 expression, consistent with the idea that they had been subject to complement selection.20 Furthermore, most studies on anti-CD20 mAb effector mechanisms have tended to consider ADCC and CDC as separate processes and thus exclude any possible cooperative activity, for example, where complement opsonization might be important for phagocytosis and regulation of immune responses. It is also unknown whether products arising from complement activation, such as the membrane attack complex (MAC), could have important signaling functions via glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)–linked receptors that might modulate signaling activity provided by anti-CD20 mAbs.21 22

The CD20 molecule is without known function or ligand, and knock-out mice show no obvious phenotype.23 It is a 33 to 37-kDa nonglycosylated surface phosphoprotein that is predicted to cross the plasma membrane 4 times, leaving a single detectable extracellular loop and the N- and C-termini inside the cell.24,25 CD20 probably exists in an oligomeric form in the plasma membrane, where it may either assist in, or directly contribute to, the formation of cellular ion channels.26,27 Until recently, blocking studies showed very limited epitope diversity in the extracellular loop of CD20, with only 2 overlapping epitopes, one recognized by the vast majority of anti-CD20 mAbs, and a second recognized by a unique reagent, 1F5.28 However, Deans and colleagues26 have just revealed a more complex situation, placing 16 anti-CD20 mAbs into 4 different subgroups according to their ability to bind to a crucial alanine-X-proline motif in the CD20 extracellular loop. These mAbs also could be grouped by their ability to translocate CD20 into the detergent-insoluble lipid microdomains, generally known as “rafts” (most mAbs), trigger extensive homotypic cellular adhesion (3 mAbs), or perform both of these activities (1 mAb). In our previous work we found that a similar panel of anti-CD20 mAbs could be subdivided into mAbs that were effective or not at inducing CDC and speculated that these functions might be related to the ability of the mAbs to translocate into membrane rafts.29 In the current study we show a close relationship between the ability of a mAb to translocate CD20 into lipid rafts and to activate lytic complement. Thus, it appears that a key effector function of a mAb may be related to its ability to redistribute target antigen into specific compartments of the plasma membrane.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Human cell lines were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC, Salisbury, United Kingdom) and maintained in antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 medium with fetal calf serum (Myoclone, 10%), glutamine (2 mM), and pyruvate (1 mM) (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom) at 37°C, 5% CO2. BCL1-3B3 is a mouse cell line derivative of the BCL1 tumor maintained in tissue culture under the conditions described above.

Antibody production and labeling

The mAbs used are shown in Table1. mAb-producing hybridomas were expanded in tissue culture and purified on Protein A column. F(ab′)2fragments of IgG were produced by standard pepsin digestions.34 Flow cytometry and 125I-labeled mAb binding were as described previously.35

Sources, specificities, and isotypes of antibodies used in study

| mAb . | Specificity . | Isotype . | Source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2H7 | CD20 | IgG2b | Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom |

| IF5 | CD20 | IgG2a | ECACC Hybridoma |

| B1 | CD20 | IgG2a | Coulter, Miami, FL |

| HI47 | CD20 | IgG3 | ECACC Hybridoma |

| Rituximab | CD20 | Chimeric Hu Fc | IDEC, San Francisco, CA |

| AT80 | CD20 | IgG1 | In-house |

| LT20 | CD20 | IgG1 | In-house |

| MB1/7 | CD37 | IgG1 | Richard Miller30 |

| WR17 | CD37 | IgG2a | Keith Moore31 |

| AT13/5 | CD38 | IgG1 | In-house |

| IB4 | CD38 | IgG2a | Fabio Malavasi32 |

| F3.3 | MHC II | IgG1 | In-house |

| A9-1 | MHC II | IgG2a | In-house |

| CAMPATH-1H | CD52 | Chimeric Hu Fc | Geoff Hale33 |

| mAb . | Specificity . | Isotype . | Source . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2H7 | CD20 | IgG2b | Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom |

| IF5 | CD20 | IgG2a | ECACC Hybridoma |

| B1 | CD20 | IgG2a | Coulter, Miami, FL |

| HI47 | CD20 | IgG3 | ECACC Hybridoma |

| Rituximab | CD20 | Chimeric Hu Fc | IDEC, San Francisco, CA |

| AT80 | CD20 | IgG1 | In-house |

| LT20 | CD20 | IgG1 | In-house |

| MB1/7 | CD37 | IgG1 | Richard Miller30 |

| WR17 | CD37 | IgG2a | Keith Moore31 |

| AT13/5 | CD38 | IgG1 | In-house |

| IB4 | CD38 | IgG2a | Fabio Malavasi32 |

| F3.3 | MHC II | IgG1 | In-house |

| A9-1 | MHC II | IgG2a | In-house |

| CAMPATH-1H | CD52 | Chimeric Hu Fc | Geoff Hale33 |

CDC assay

Serum for complement lysis was prepared as follows: blood from healthy volunteers was allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 to 60 minutes and then centrifuged at 900g for 20 minutes. Serum was harvested and then either used fresh or stored at −80°C. To determine the CDC activity of the various mAbs, elevated membrane permeability was assessed using a rapid and simple propidium iodide (PI) exclusion assay, as previously described.36

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis

mAbs were directly conjugated to bisfunctional N-hydrosuccinimidyl (NHS)–ester derivatives of Cy3 and Cy5 (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) as described in the manufacturer's instructions. The labeled mAb was isolated using a PD10-Sephadex G25 column. Molar ratios of coupling were determined spectrophotometrically from ε552 = 150/mM/cm for Cy3, ε650 = 250/mM/cm for Cy5, and ε280 = 170/mM/cm for protein, and ranged from 5- to 8-fold excess dye/protein. Aggregates were removed by centrifugation.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) analysis was based on the method described previously.37 Cells were resuspended at 3 × 106 cells/mL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/1% heat-inactivated mouse and human serum, and equimolar donor (Cy3)–conjugated and acceptor (Cy5)–conjugated mAbs were combined and added to the cell suspension (10 μg/mL, final). Cells were incubated for 50 minutes in the dark, on ice, or at 37°C. Each experiment included cells labeled with donor- and acceptor-conjugated mAbs after preincubation with a 20-fold molar excess of unconjugated mAbs, and cells labeled with donor- or acceptor-conjugated mAbs in the presence of equimolar unlabeled mAbs. FRET was assessed using flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The fluorescence intensities at 585 nm (FL2) and 650 nm (FL3), both excited at 488 nm, and the fluorescence intensity at 661 nm (FL4), excited at 635 nm, were detected and used to calculate FRET according to the equation below, where A is acceptor (Cy5) and D is donor (Cy3). All values obtained were corrected for autofluorescence:

FRET = FL3(D, A) − FL2(D, A)/a − FL4(DA)/b, where: a = FL2(D)/FL3(D), and b = FL4(A)/FL3(A).

Correction parameters were obtained using data collected from single-labeled cells, and side scatter was used to gate out dead cells. FRET between donor and acceptor mAbs on the cells is expressed as acceptor sensitized emission at 488 nm.37Larger FRET efficiencies suggest closer association of the donor and acceptor mAbs or a high density of acceptor mAbs in the vicinity of donor mAbs.38 39

Preparation of lipid raft fractions and Western blotting

Monoclonal Ab (1 μg/106 cells) was added to cells at 37°C. Following 20 minutes' incubation, cells were pelleted and lysed in ice-cold 1.0% Triton X-100 in 2-[N-morpholino] ethanesulfonic acid (MES)–buffered saline (25 mM MES, pH 6.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/mL aprotinin, 5 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid]). Lipid raft fractions were then prepared by sucrose density gradient centrifugation as described by Deans et al.40 Fractions were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto polyvinylidenefluoride membranes, and incubated with primary antibody (mouse anti-CD20, clone 7D1, or anti-Lyn rabbit polysera; Serotec, United Kingdom), followed by horseradish-peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham Biosciences). Blots were visualized using ECL+plus (Amersham Biosciences).

Assessment of raft-associated antigen by Triton X-100 insolubility

As a rapid assessment of antigen presence in raft microdomains, we used a flow cytometry method based on Triton X-100 insolubility at low temperatures, as described previously.41 42 In brief, cells were washed in RPMI/1% BSA and resuspended at 2.5 × 106/mL. Cells were then incubated with 10 μg/mL of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated mAbs for 15 minutes at 37°C, washed in cold PBS/1% BSA/20 mM sodium azide, and then the sample divided in half. One half was maintained on ice to allow calculation of 100% surface antigen levels, while the other was treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes on ice to determine the proportion of antigens remaining in the insoluble raft fraction. Cells were then maintained at 4°C throughout the remainder of the assay, washed once in PBS/BSA/azide, resuspended, and assessed by flow cytometry as detailed above. Similar results were obtained using indirect methods of detection. To determine the constitutive level of raft association of target antigens, cells were first treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes on ice and washed in PBS/BSA/azide prior to binding of FITC-labeled mAbs. To assess whether more antigen could be moved into the Triton X-100–insoluble fraction by additional cross-linking, cells were incubated with FITC-mAb as before, washed, and then divided into 4 samples. Two of these samples were incubated with goat anti–mouse Ig F(ab′)2 fragments for 15 minutes on ice. After washing, one of the cross-linked and one of the non–cross-linked samples were lysed in Triton X-100 and washed as detailed above, prior to flow cytometry.

Transfection of YFP-Hu CD20 and confocal microscopy

A chimera of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fused to the C-terminal region of human CD20 (YFP-Hu20) was constructed by fusing full-length human CD20 into the pEYFP-C1 plasmid (Clontech, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) via XhoI and BamHI sites. YFP-Hu20 transfections of BCL1-3B3 cells were carried out using the GenePorter reagent (Gene Therapy System, San Diego, CA) and transfectants selected with geneticin (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) and identified by flow cytometry.

For visual redistribution studies, cells were stimulated with mAbs (10 μg/mL) for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then cytospun, fixed (3.7% paraformaldehyde), washed, and mounted in Mowiol (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, San Diego, CA) with 0.1% Citifluor (Agar Scientific, Stanstead, United Kingdom). YFP-HuCD20 clustering was visualized using a Leica SP2 confocal microscope (Bannockburn, IL).

Results

CD20 mAb mediates potent recruitment of complement

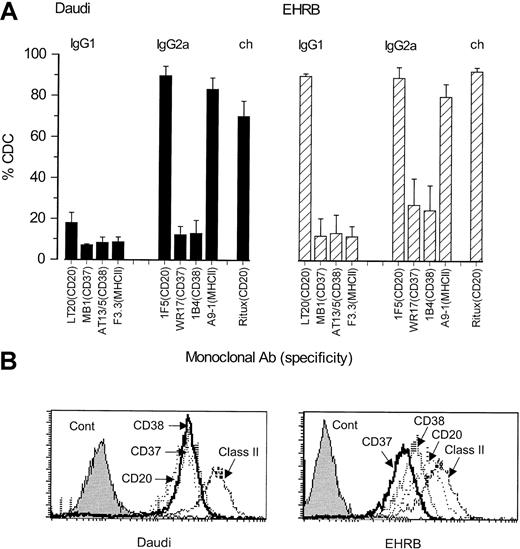

Recently, we have been struck by the unusual potency with which CD20 mAbs recruit human complement for the lysis of B-cell lymphoma cells. Figure 1 shows CDC results for a panel of IgG1 and IgG2a isotype mAbs directed at CD20, CD37, CD38, and MHCII. Ritux (chimeric Ab, with human IgG1κ constant domains) is included as a positive control. Against both Daudi and EHRB cells, the rodent anti-CD20 mAbs were consistently the most active of these reagents in CDC, usually mediating lysis of approximately 90% of the target cells. Such results cannot be explained by the relative levels of binding, because flow cytometric analysis showed that the anti-MHCII mAb bound at the highest levels (Figures 1B and 5 show the mean fluorescence intensity [MFI] of these mAbs) and yet were not the most active. The differences in potency were most striking when comparing IgG1 isotype mAbs, because under these conditions only the CD20 reagents initiated detectable CDC (18% and 90% lysis of Daudi and EHRB cells, respectively).

CDC activity and binding levels of various antibodies directed to the B-cell surface.

(A) CDC induced by a panel of mouse IgG1 and IgG2a isotype mAbs directed at CD20, CD37, CD38, and MHCII. Daudi (▪) or EHRB (▨) cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with mAbs (10 μg/mL) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Normal human serum (NHS, 20% vol/vol) was then added as a source of complement and the cells incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Cell lysis was assessed by flow cytometry using a PI exclusion assay, and the level of CDC expressed as PI-positive cells as a percentage of total cells. The results show the means and SDs of 3 separate experiments. (B) Surface expression of CD20, CD37, CD38, and MHCII antigens on Daudi or EHRB cells. Daudi or EHRB cells (5 × 105/mL) were incubated with mAbs (10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at room temperature, then washed and incubated with goat anti–mouse IgG F(ab′)2 FITC for 30 minutes on ice, prior to washing and analysis by flow cytometry.

CDC activity and binding levels of various antibodies directed to the B-cell surface.

(A) CDC induced by a panel of mouse IgG1 and IgG2a isotype mAbs directed at CD20, CD37, CD38, and MHCII. Daudi (▪) or EHRB (▨) cells (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with mAbs (10 μg/mL) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Normal human serum (NHS, 20% vol/vol) was then added as a source of complement and the cells incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Cell lysis was assessed by flow cytometry using a PI exclusion assay, and the level of CDC expressed as PI-positive cells as a percentage of total cells. The results show the means and SDs of 3 separate experiments. (B) Surface expression of CD20, CD37, CD38, and MHCII antigens on Daudi or EHRB cells. Daudi or EHRB cells (5 × 105/mL) were incubated with mAbs (10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at room temperature, then washed and incubated with goat anti–mouse IgG F(ab′)2 FITC for 30 minutes on ice, prior to washing and analysis by flow cytometry.

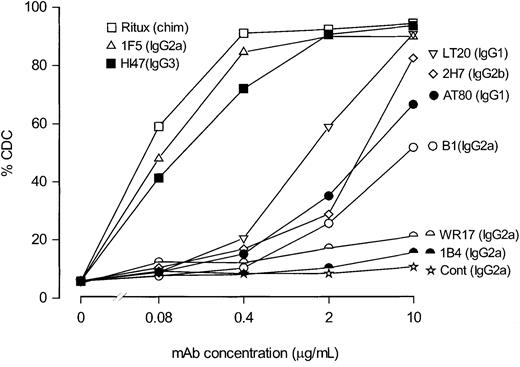

Potency of different anti-CD20 mAbs in complement-mediated lysis

To investigate whether this high CDC activity was a property of all anti-CD20 mAbs, we compared a large panel of anti-CD20 mAbs that included the clinically relevant Ritux and B1 reagents. Figure2 shows that the mAbs could be divided into 2 distinct groups by this assay: the first, which included Ritux, 1F5, and HI47, contained reagents that were potent in CDC; the second, which included AT80, 2H7, LT20, and B1, contained those with relatively poor cytolytic activity. In most cases such activity is explicable on the basis of mAb isotype with human IgG1, mouse IgG2a, and IgG3 performing well, and mouse IgG1 and IgG2b performing poorly. It is important to bear in mind that even this poorly performing group was surprisingly active given that mouse IgG1 mAbs are generally considered unable to recruit human complement.43 44 Indeed, these mAbs were more active than those carrying the mouse IgG2a isotype, directed to the CD37 and CD38 antigens. The one exception in this distribution was B1, which, despite being a mouse IgG2a, performs poorly in CDC. It also should be noted that kinetics of CDC were examined in preliminary experiments, which revealed that optimal lysis with 1F5 was observed as early as 5-10 minutes after the addition of serum. However, our CDC assays were routinely performed for 30-45 minutes to allow suboptimal mAbs to induce their maximal CDC activity. Longer durations (ie, > 45 minutes) were not assessed to minimize other forms of cell death, for example, apoptosis.

Dose dependence of CDC activity with different anti-CD20 mAbs.

To determine the relative efficacy with which various anti-CD20 mAbs evoked CDC, mAbs were titrated from 10 to 0.08 μg/mL and incubated with EHRB cells for 15 minutes; NHS was added at 20% and assessed for CDC activity as detailed in the legend to Figure 1. As controls, anti-CD37 (WR17) and anti-CD38 (1B4) mAbs were included and assessed in the same manner.

Dose dependence of CDC activity with different anti-CD20 mAbs.

To determine the relative efficacy with which various anti-CD20 mAbs evoked CDC, mAbs were titrated from 10 to 0.08 μg/mL and incubated with EHRB cells for 15 minutes; NHS was added at 20% and assessed for CDC activity as detailed in the legend to Figure 1. As controls, anti-CD37 (WR17) and anti-CD38 (1B4) mAbs were included and assessed in the same manner.

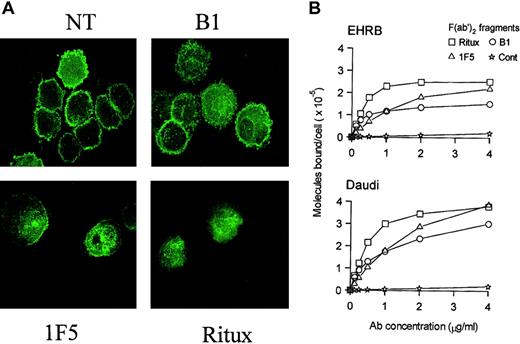

Binding properties of CD20 mAbs on B-cell lines

We next investigated the relative binding activity of these mAbs using radiolabeled F(ab′)2 fragments to see if this might explain the differences in complement activity. Figure3A shows saturation curves that confirmed the binding constants for Ritux (5-8 × 10-9 M), B1 (3-6 × 10-9 M), and 1F5 (1-3 × 10-8 M) on Daudi and EHRB cells. Each mAb gave a range of affinities, indicating interexperimental variation and binding activity on different cell lines. Radiolabeled IgG gave similar curves (results not shown, except for 1F5 IgG binding to EHRB cells), showing that the Fc region was not involved in binding to the cells. The surprising finding was that B1 and Ritux, despite binding to the same target CD20 loop with high affinity, saturated at different levels, with Ritux binding almost twice as many molecules on each cell. 1F5 has a weaker binding affinity but, despite generating flatter binding curves, eventually reaches similar levels of binding to those achieved by Ritux. These differences are the subject of ongoing investigation. Despite these distinct binding patterns, we do not believe that they explain the observed differences in CDC activity, mainly because 1F5 and Ritux gave clear cytotoxic activity at concentrations well below their binding maxima. For example, Figure 2 shows that even at 0.08 μg/mL, a concentration that would have achieved less than 20% Ritux or 10% 1F5 saturation (Figure 3A), we recorded at least 50% lysis for Ritux and 1F5. In contrast, B1 could achieve this level of lytic activity only when added at 10 μg/mL, representing 125 times less potency. We conclude that at saturation, B1 is capable of reaching levels on the cell that should mediate CDC as effectively as 1F5 or Ritux.

Binding and redistribution properties of different anti-CD20 antibodies.

(A) Binding of 125I-labeled F(ab′)2 fragments of 1F5, Ritux, and B1 anti-CD20 mAbs to EHRB and Daudi cells.125I-labeled F(ab′)2 fragments of anti-CD20 or control (anti-CD3) mAbs were incubated with Daudi or EHRB cells for 2 hours at 37°C. The exception to this is the curve for IF5 binding to Daudi cells, for which 125I-labeled whole IgG was used. The cell-bound and free 125I-labeled mAbs were then separated by centrifugation through phthalate oils and the cell pellets together with bound antibody counted for radioactivity. (B) 1F5 and Ritux, but not B1, induce clustering of YFP-HuCD20 in BCL1-3B3–transfected cells upon binding to CD20. BCL1-3B3 cells transfected with YFP-HuCD20 were incubated with various anti-CD20 mAbs for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then cytospun onto slides and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. YFP-HuCD20 clustering was visualized using confocal microscopy. Representative images from 3 separate experiments are shown (original magnification, × 100). During this investigation we performed microscopic examination of anti-CD20 mAbs binding to cells using FITC-mAbs. These experiments revealed clear differences in the distribution of CD20.

Binding and redistribution properties of different anti-CD20 antibodies.

(A) Binding of 125I-labeled F(ab′)2 fragments of 1F5, Ritux, and B1 anti-CD20 mAbs to EHRB and Daudi cells.125I-labeled F(ab′)2 fragments of anti-CD20 or control (anti-CD3) mAbs were incubated with Daudi or EHRB cells for 2 hours at 37°C. The exception to this is the curve for IF5 binding to Daudi cells, for which 125I-labeled whole IgG was used. The cell-bound and free 125I-labeled mAbs were then separated by centrifugation through phthalate oils and the cell pellets together with bound antibody counted for radioactivity. (B) 1F5 and Ritux, but not B1, induce clustering of YFP-HuCD20 in BCL1-3B3–transfected cells upon binding to CD20. BCL1-3B3 cells transfected with YFP-HuCD20 were incubated with various anti-CD20 mAbs for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then cytospun onto slides and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. YFP-HuCD20 clustering was visualized using confocal microscopy. Representative images from 3 separate experiments are shown (original magnification, × 100). During this investigation we performed microscopic examination of anti-CD20 mAbs binding to cells using FITC-mAbs. These experiments revealed clear differences in the distribution of CD20.

During this investigation we performed microscopic examination of anti-CD20 mAb binding to cells using FITC-mAb. These experiments revealed clear differences in the distribution of CD20 bound by the different mAbs, in that B1 bound over the cell surface homogeneously, while other anti-CD20 mAbs appeared to bind in clusters, revealed by punctate staining (data not shown). In order to investigate this phenomenon more closely, we used a mouse cell line (BCL1-3B3) transfected to express YFP-tagged human CD20, which bypasses any variation in mAb-FITC conjugation and the need of secondary amplifying reagents. These data reveal (Figure 3B) that, as in the Burkitt lines, B1 caused minimal redistribution of CD20 upon binding, while other anti-CD20 mAbs such as Ritux and 1F5 caused marked clustering of YFP-CD20.

Redistribution of CD20 and anti-CD20 mAbs on target cells

The reorganization of CD20 in the plasma membrane following binding by mAbs is likely to be important in providing the appropriate distribution of Fc regions for the recruitment of C1q and the triggering of the classical pathway of complement. To examine this reorganization further, we used FRET analysis to measure the molecular proximity of anti-CD20 mAbs on intact Daudi and EHRB cells. In these experiments, separate batches of each anti-CD20 mAb were labeled with Cy3 or Cy5 and energy transfer values obtained for 50:50 mixtures of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled mAbs (eg, B1 Cy3 + B1 Cy5). For comparison, 3 other non-CD20 mAb specificities were similarly assessed (MHCII, CD37, and CD38). A high FRET value indicates close proximity of neighboring Cy3- and Cy5-labeled mAbs38 39 and can be caused either by mAb binding to a surface molecule that is expressed at high density or by mAb ligation causing redistribution and closer association of the molecular target. Figure 4A shows histograms from a typical experiment, illustrating FRET data for Ritux and B1 (open histograms) compared with controls (shaded histograms). The clear shift in the open histogram with Ritux represents demonstrable FRET due to the close proximity of the acceptor and donor-labeled mAbs. In comparison, B1 generated insignificant levels of FRET. These experiments were performed 3 times with the panel, and the results are presented as a bar chart in Figure 4B. The results show that while Ritux and 1F5 were very effective in this assay, with Ritux recording between 50 and 70 FRET units on EHRB and Daudi cells, respectively, B1, which was poor at activating complement, was completely inactive in generating a FRET signal. In this regard, it performed like anti-CD37 and anti-CD38 mAbs, other targets that are relatively poor in CDC. For both Ritux and 1F5, the levels of FRET were higher at 37°C than at 4°C. Because the plasma membrane is more mobile at higher temperatures, these results are consistent with FRET values being dependent on molecular reorganization in the plasma membrane rather than on antigen density. Conversely, mAb binding to MHCII gave only a modest level of FRET, which was not greatly enhanced at 37°C, indicating that these FRET values were predominantly due to the high surface expression of MHCII. Thus, these results indicate a good correlation between the ability of a mAb to perform CDC and to mediate FRET.

Comparison of the abilities of antibodies to redistribute antigens on the cell surface assessed by FRET and Triton X-100 insolubility.

Analysis of CD20 FRET (A and B) and the association of CD20 into membrane rafts (C) in the presence of various anti-CD20 mAbs. (A) Homoassociation analysis of CD20 with B1 and Ritux mAb. Daudi cells were labeled with equimolar mixtures of Cy5 (acceptor)–conjugated mAbs and either unconjugated mAbs (filled histograms) or Cy3 (donor)–conjugated mAbs (open histograms) for 50 minutes at 37°C. Associations were estimated by flow cytometric analysis as described in “Materials and methods.” (B) Comparison of FRET with anti-CD20, anti-MHCII (A9-1), anti-CD37 (WR17), and anti-CD38 (1B4). EHRB and Daudi cells were labeled with equimolar mixtures of Cy3 (donor)– and Cy5 (acceptor)–conjugated mAb pairs for 50 minutes at 4°C (▩) or 37°C (▪) as indicated. Associations were estimated by flow cytometric analysis as described in “Materials and methods.” Data illustrate FRET values ± SEMs, expressed in terms of Cy5 emission at 488 nm, for 3 independent experiments for CD20, MHCII, CD37, and CD38 homoassociation as indicated. (C) Daudi cells were treated with anti-CD20 mAbs (B1, Ritux, 1F5, as indicated) or left untreated (Cont, Ct/Lyn), lysed after 20 minutes in 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer, and fractionated on a discontinuous sucrose gradient as described in “Materials and methods.” Gradient fractions were resolved on 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate gels, and Western blots developed using 7D1 primary antibody to identify CD20 or rabbit anti-Lyn polyclonal antisera. The pelleted fraction from each sucrose density gradient did not contain CD20 (data not shown).

Comparison of the abilities of antibodies to redistribute antigens on the cell surface assessed by FRET and Triton X-100 insolubility.

Analysis of CD20 FRET (A and B) and the association of CD20 into membrane rafts (C) in the presence of various anti-CD20 mAbs. (A) Homoassociation analysis of CD20 with B1 and Ritux mAb. Daudi cells were labeled with equimolar mixtures of Cy5 (acceptor)–conjugated mAbs and either unconjugated mAbs (filled histograms) or Cy3 (donor)–conjugated mAbs (open histograms) for 50 minutes at 37°C. Associations were estimated by flow cytometric analysis as described in “Materials and methods.” (B) Comparison of FRET with anti-CD20, anti-MHCII (A9-1), anti-CD37 (WR17), and anti-CD38 (1B4). EHRB and Daudi cells were labeled with equimolar mixtures of Cy3 (donor)– and Cy5 (acceptor)–conjugated mAb pairs for 50 minutes at 4°C (▩) or 37°C (▪) as indicated. Associations were estimated by flow cytometric analysis as described in “Materials and methods.” Data illustrate FRET values ± SEMs, expressed in terms of Cy5 emission at 488 nm, for 3 independent experiments for CD20, MHCII, CD37, and CD38 homoassociation as indicated. (C) Daudi cells were treated with anti-CD20 mAbs (B1, Ritux, 1F5, as indicated) or left untreated (Cont, Ct/Lyn), lysed after 20 minutes in 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer, and fractionated on a discontinuous sucrose gradient as described in “Materials and methods.” Gradient fractions were resolved on 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate gels, and Western blots developed using 7D1 primary antibody to identify CD20 or rabbit anti-Lyn polyclonal antisera. The pelleted fraction from each sucrose density gradient did not contain CD20 (data not shown).

On the basis of this information, we decided to investigate the association of CD20 with lipid rafts. It is known that, without cross-linking, CD20 is not associated with rafts and is readily soluble in nonionic detergents such as TX-100, at low temperatures.40,45 We investigated the distribution of CD20 between the raft and nonraft membrane fractions using the sucrose gradient fractionation method described by Deans and colleagues.40 Figure 4C shows that following sucrose gradient fractionation of Triton X-100–solubilized Daudi cells, CD20 molecules are confined to high-density fractions 6-8. Cells treated with B1 for 30 minutes showed a similar CD20 distribution to untreated cells, in fractions 6-8. In contrast, cells treated with Ritux or 1F5 showed a distinct shift in CD20 distribution with a significant proportion now found in the lower density fractions 4, or 3 and 4, respectively, coincident with where membrane rafts are expected to occur. To verify the location of rafts in our preparations, we reprobed the membranes for Lyn (Figure 4C), a known raft marker that, as expected, was found in the low-density fractions.3-5 Thus, it appears that the ability of anti-CD20 mAbs to demonstrate FRET and activate complement shows a tight correlation with the ability to redistribute CD20 into membrane rafts. The distinct redistribution of CD20 to fraction 4 following cross-linking with Ritux, compared with fractions 3 and 4 with 1F5 treatment, was a consistent but unexplained finding (Figure 4B).

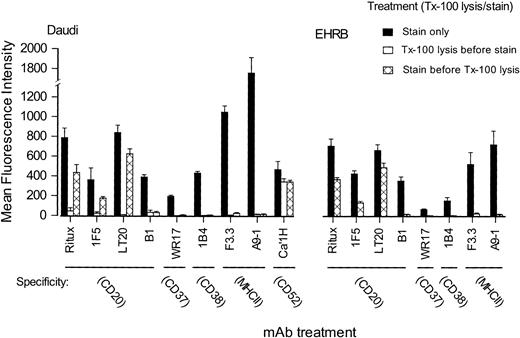

CD20 becomes Triton X-100–insoluble when cross-linked by mAbs

To continue these investigations and study a range of other antigen specificities without having to perform sucrose gradient sedimentation and Western blotting, we moved to a flow cytometric method in which cells are treated with dilute Triton X-100 before or after staining with fluorescent mAbs.41 42 Under the conditions used, it is possible to remove nonraft lipid and most of the cytoplasm from the cells, leaving only the insoluble parts of the cell together with the lipid rafts. Figure 5shows staining of Daudi and EHRB cells, first using mAbs on intact cells (solid bars), then on cells that have been treated with Triton X-100 before staining with mAbs (open bars, not shown for EHRB), and finally for cells stained with mAbs and then treated with Triton X-100 (hatched bars). The results clearly show that in all cases except one, treating with Triton X-100 removes all cell-associated molecules, making them unavailable for staining. The one exception is Campath (CD52), which is GPI-linked and therefore constitutively associated with the outer leaflet of rafts. The GPI-linked molecules CD55 and CD59 are similarly retained following such treatment (data not shown). These results are consistent with raft material being retained with the Triton X-100–treated cells in this technique. EHRB cells do not express GPI-linked proteins and therefore do not express CD52. In contrast to this situation, when the cells were stained with these mAbs before being treated with Triton X-100 (hatched bars), we found that most anti-CD20 mAbs remained with the cells. Furthermore, B1, the one anti-CD20 mAb that did not move CD20 into rafts, also failed to remain with the Triton X-100–treated cells. All other mAb specificities, with the exception of CD52, failed to remain with the Triton X-100 insoluble fraction.

Triton X-100 insolubility of different surface antigens before and after binding of mAbs.

Daudi or EHRB cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL FITC-mAbs for 15 minutes at 37°C, before washing and dividing the sample in half. One half was maintained on ice in PBS (▪), allowing calculation of 100% binding levels, while the other was treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 (labeled Tx-100) for 15 minutes on ice (▩; stained before Triton X-100 lysis). Cells then were washed once, resuspended, and assessed by flow cytometry. To determine levels of constitutively Triton X-100–insoluble antigens, cells were treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes on ice and washed prior to staining with FITC-mAbs (■; Triton X-100 lysis before staining). Shown are the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values for each sample. Error bars show ± SD of triplicate samples.

Triton X-100 insolubility of different surface antigens before and after binding of mAbs.

Daudi or EHRB cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL FITC-mAbs for 15 minutes at 37°C, before washing and dividing the sample in half. One half was maintained on ice in PBS (▪), allowing calculation of 100% binding levels, while the other was treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 (labeled Tx-100) for 15 minutes on ice (▩; stained before Triton X-100 lysis). Cells then were washed once, resuspended, and assessed by flow cytometry. To determine levels of constitutively Triton X-100–insoluble antigens, cells were treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes on ice and washed prior to staining with FITC-mAbs (■; Triton X-100 lysis before staining). Shown are the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values for each sample. Error bars show ± SD of triplicate samples.

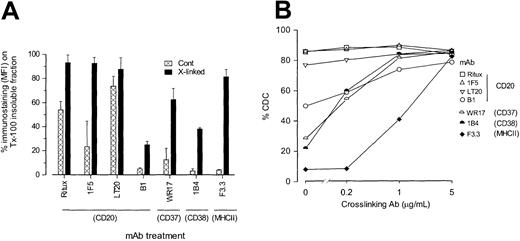

Given that the ability of anti-CD20 mAbs to move CD20 into rafts appeared to correlate with the ability to cross-link neighboring CD20 molecules, we next asked if more surface molecules became associated with the Triton X-100 insoluble fraction as they were cross-linked. Figure 6A shows very clearly that as the primary mAbs became cross-linked with F(ab′)2 fragments of polyclonal anti-Ig Abs, so more molecules were able to remain with the cells following treatment with Triton X-100. Under these conditions, all mAbs, including B1, showed a proportion of binding remaining following detergent treatment. In the most striking case, 80% of MHCII molecules remained with the Triton X-100–treated cells following hyper–cross-linking of the mAbs, whereas only 4% remained when additional cross-linking was not added. In contrast, B1 appeared the most reluctant to move into the insoluble fraction, and in this case about 25% of the mAbs remained after the detergent treatment.

Ability of cross-linking to enhance Triton X-100 insolubility and CDC activity of different antigens.

(A) To assess whether more antigen could be moved into the Triton X-100–insoluble fraction by additional cross-linking, EHRB cells were incubated with FITC-mAbs as before, washed, and then divided into 4. Two of these samples were incubated with goat anti–mouse IgG F(ab′)2 fragments for 15 minutes on ice to facilitate cross-linking. After washing, one of the cross-linked and one of the non–cross-linked samples were lysed in Triton X-100 and washed as detailed above, and the remaining 2 samples retained to determine total binding with and without cross-linking. Results were then expressed as the percent of antigen retained in the Triton X-100–insoluble fraction using the equations: (MFI Triton X-100 insoluble/MFI total) × 100 and (MFI cross-linked Triton X-100/MFI cross-linked total) × 100 for non–cross-linked and cross-linked, respectively. Error bars represent SD of results for at least 3 experiments. (B) To assess whether cross-linking could enhance CDC activity, mAb (10 μg/mL) was bound to cells for 15 minutes at room temperature as before and then washed once, prior to addition of cross-linking agent at a range of concentrations (0, 5, 1, 0.2 μg/mL) for 10 minutes at room temperature. NHS (5% vol/vol) was then added and CDC measured as described in the legend to Figure 1. Similar data were obtained in 3 experiments.

Ability of cross-linking to enhance Triton X-100 insolubility and CDC activity of different antigens.

(A) To assess whether more antigen could be moved into the Triton X-100–insoluble fraction by additional cross-linking, EHRB cells were incubated with FITC-mAbs as before, washed, and then divided into 4. Two of these samples were incubated with goat anti–mouse IgG F(ab′)2 fragments for 15 minutes on ice to facilitate cross-linking. After washing, one of the cross-linked and one of the non–cross-linked samples were lysed in Triton X-100 and washed as detailed above, and the remaining 2 samples retained to determine total binding with and without cross-linking. Results were then expressed as the percent of antigen retained in the Triton X-100–insoluble fraction using the equations: (MFI Triton X-100 insoluble/MFI total) × 100 and (MFI cross-linked Triton X-100/MFI cross-linked total) × 100 for non–cross-linked and cross-linked, respectively. Error bars represent SD of results for at least 3 experiments. (B) To assess whether cross-linking could enhance CDC activity, mAb (10 μg/mL) was bound to cells for 15 minutes at room temperature as before and then washed once, prior to addition of cross-linking agent at a range of concentrations (0, 5, 1, 0.2 μg/mL) for 10 minutes at room temperature. NHS (5% vol/vol) was then added and CDC measured as described in the legend to Figure 1. Similar data were obtained in 3 experiments.

Monoclonal antibodies mediate complement lysis more efficiently when transferred into the detergent-insoluble fraction of the cell membrane

Finally, we asked if cross-linking a primary mAb in this way not only shifted the target to the more insoluble part of the plasma membrane but also changed the ability of the mAb to activate complement. Figure 6B shows that for all mAbs investigated, additional cross-linking with F(ab′)2 anti-Ig promoted CDC. This was particularly striking in the case of the anti-MHCII IgG1 mAb, which, without cross-linking, was unable to lyse cells but became as potent as Ritux when cross-linked with 5 μg/mL F(ab′)2 anti-Ig. Similar potentiation in CDC was obtained when the IgG2a mAb against CD37 (WR17) and CD38 (1B4) were treated with just 1 μg/mL F(ab′)2 anti-Ig. Interestingly, the B1 mAb (IgG2a) against CD20, which was least inclined to move into the Triton X-100 insoluble fraction following cross-linking (Figure 6A), also showed an appreciable improvement in CDC activity following the addition of the polyclonal cross-linker. Thus, in each case, a treatment that is known to drive Ab:Ag complexes into a detergent-insoluble fraction, which includes membrane rafts, improves the ability of mAbs to recruit lytic complement.

Discussion

The ability of mAbs to recruit and activate complement at the cell surface is dependent not only on isotype and target density but also the lateral mobility of Ab:Ag complexes in the plasma membrane and the distance between the target epitope and the lipid bilayer.46 Thus, the specificity of mAbs can have profound and subtle influences on the efficiency with which complement is recruited. Here we have shown that anti-CD20 mAbs are unusually effective at recruiting complement for the lysis of neoplastic B cells and that this activity is closely linked to the ability of the mAbs to translocate CD20 into membrane rafts following ligation.26,40 45 All but one of the anti-CD20 mAbs were effective in mediating CD20 raft translocation and in recruiting human complement in CDC assays. The exception, B1, was unable to deliver CD20 into rafts and, despite being of a complement-activating isotype (IgG2a) and causing C1s and C3 deposition equivalent to 1F5 in solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay experiments (data not shown), failed to lyse cells in CDC.

It is not clear why translocation of Ab:Ag complexes into lipid rafts should influence the ability of mAbs to activate complement so markedly, even to the point where mouse IgG1 anti-CD20 isotypes, which normally activate human complement comparatively poorly, were able to lyse malignant B cells.43,44 Because of the requirement for at least 2-headed binding to engage and activate C1q, the most straightforward explanation is that concentrating mAbs into a comparatively small area of the plasma membrane provides an ideal density of juxtaposed Fc regions for engaging the C1q heads, thereby triggering the classical complement pathway.47,48 Our FRET data give good support for this suggestion, showing that ligation of CD20 by complement-lytic mAbs is associated with a sharp rise in FRET, consistent with the Ab:Ag complexes becoming redistributed into rafts. A second possibility is that the cholesterol-rich environment provided by rafts is advantageous for complement activation through C3 deposition or by providing a region of the membrane that is more susceptible to penetration by MAC, perhaps because the lipid is more rigid or the MAC are less likely to be removed by internalization. Previous work supports this, showing that red blood cells became more susceptible to lysis as their cholesterol content was increased.49 50 We are currently investigating these 2 possibilities by asking whether the relative potency of anti-CD20 mAbs lies in their ability to activate C1, that is, provide an optimal Fc binding platform, or in the efficiency with which they use MAC, that is, membrane penetration. It is interesting that most complement-defense molecules, being GPI-linked, are constitutively associated with rafts and consequently ideally placed to protect cells from any damage focused on the rafts.

Cross-linking of cell-surface antigen by fluid-phase antibody, with subsequent aggregation and lateral movement of Ab:Ag complexes, has long been associated with the phenomenon of antigenic modulation, whereby the cell acquires resistance to complement lysis induced by that antibody.51 This process can be inhibited with azide or by using univalent mAbs that are unable to provide cross-linking activity.52 With many target antigens, such as the thymus leukemia antigen TL and the B-cell receptor BCR, the redistribution of Ab:Ag complexes is followed by their internalization and degradation, leaving the cell free of target antigen. Thus, antigenic modulation and internalization often has been cited as one of the reasons certain mAb specificities fail to perform in the clinic and may partly explain why anti-CD20 mAbs, which do not modulate or internalize even in vivo,53 are effective in CDC and clinically successful. Interestingly, we have shown previously that when the target antigen concerned is the BCR on leukemic B lymphoblasts, anti–complement modulation was established in 2 to 5 minutes following exposure to anti-Ig at 37°C and appeared to require only limited surface reorganization of Ab:Ag complexes on the cell surface.54 55 This modulated state occurred sufficiently rapidly to protect the cell when lytic syngeneic complement was present and persisted in the presence of “patched” Ab:Ag complexes on the surface. It is not clear at this stage what relationship this patched material has to lipid rafts, but recent cell signaling studies show that the BCR can become raft-associated following cross-linking in some B-cell types. The situation in the current work appears quite different, since here we find that redistribution of anti-CD20:CD20 complexes on the cell surface was required for full CDC activity. Furthermore, the complement-activating activity of other anti–B-cell mAbs (anti-CD37, -CD38, and -MHCII) also was promoted following cross-linking with F(ab′)2 anti-Ig and movement into the detergent insoluble fraction of the plasma membrane. Thus, our earlier observations, taken in conjunction with the present report, suggest that a critical decision may be made when Ab:Ag complexes, presumably with their attached C1, are reorganized into lipid rafts. Complement lysis is either potentiated, as in the case of anti-CD20 and some other anti–B-cell mAbs (current work), or it is diminished, as can occur with anti-BCR and anti-TL Abs in certain cells. Further work will be required to understand the processes that control these molecular decisions.

Recently, Polyak and Deans26 showed that recognition of CD20 by most mAbs depends on an alanine and a proline at positions 170 and 172, respectively, in the extracellular loop of human CD20. Simply introducing these 2 residues into the equivalent positions of the mouse sequence reconstituted the binding of a range of mAbs, including B1 and Ritux. However, although this work underlined the subtleties in epitope specificity for anti-CD20 mAbs and showed that mAbs with apparently similar specificities can have quite distinct functions, it did not reveal which features of a mAb controlled translocation of CD20 into rafts. CD20 is an unusual plasma membrane molecule in terms of its ability to translocate into lipid rafts following ligation by mAbs.40,45 Most surface molecules either are constitutively associated with rafts, such as GPI-linked receptors, or remain excluded from rafts even following mAb ligation. In the current work we confirmed CD52 to be constitutively present in rafts, while CD37, CD38, and MHCII are excluded even after ligation by mAbs. There are only 2 published examples, B1 and Bly1, of mAbs that do not deliver CD20 into rafts.26 However, data presented here suggest that following hyper–cross-linking with polyclonal F(ab′)2anti-Ig, B1 was at least partially translocated into the detergent-insoluble fraction of the cell. Simultaneously, B1 became more active in CDC and interestingly, hyper–cross-linking other B-cell targets in this way, such as MHCII, CD37, and CD38, also delivered them into a detergent-insoluble fraction and improved CDC activity. Thus, movement of membrane proteins into rafts appears directly related to the degree of cross-linking provided by the ligating agents, and we suggest that this unusual property of CD20 in part relates to the degree of cross-linking that most anti-CD20 mAbs are able to provide to CD20 on the surface of B cells.

An alternative explanation for the unusual activity of CD20 may relate to its topology within the plasma membrane. Evidence from a number of studies has suggested that CD20 exists as a multimer in the surface membranes of B cells, with 4 self-associated CD20 monomers or with a mixture of CD20 monomers and other plasma membrane molecules.26,27 Polyak et al45 identified a short stretch of membrane proximal sequence in the cytoplasmic carboxyl tail of CD20 that appears important for redistribution into rafts following mAb ligation. One postulated function for such a motif is promoting oligomerization of CD20, perhaps via protein-protein interactions. Thus, one may envisage that CD20 resides in nonraft regions of the membrane, perhaps as multimers, as inactive or incomplete ion channels. Ligation by most anti-CD20 mAbs causes efficient cross-linking of neighboring molecular complexes, resulting in aggregation of CD20 molecules and translocation into rafts. However, perhaps in the case of rare mAbs such as B1, the recognized epitope favors a different mode of binding. Studies using radiolabeled Fab′ (not shown) and F(ab′)2 fragments (Figure 3) show that B1 binds to cells bivalently. The most logical explanation for our findings is that B1 binds 2 CD20 molecules within a single CD20 multimer, while other anti-CD20 mAbs tend to engage neighboring CD20 multimers. A similar situation has been described for anti–V region mAb binding to surface IgM, with some mAbs preferring to bind between BCR and others engaging both Fab arms on the same BCR.56The functional consequences of such binding were seen in the readiness with which these 2 types of reagent caused redistribution of the BCR into patches and caps and in the propensity with which they evoked apoptosis.57 Interestingly, in the current work, binding studies showed that at equilibrium, approximately half as many radiolabeled B1 molecules bound as did Ritux and 1F5 (Figure 3A), supporting the proposal that B1 binds in an unusual configuration.

It is not known at this time whether translocation of CD20 into membrane rafts is important for the activity of anti-CD20 mAbs in patients. Although the potency of Ritux indicates that mAbs that move CD20 into rafts can be highly therapeutic, there is currently little convincing evidence that complement plays a significant part in this activity.14,15 However, what is not clear is whether a humanized version of B1, because it does not move CD20 into rafts, would provide a more or less potent reagent. While B1 has been used extensively in clinical trials, its role has been as a carrier for radioactive 131I, tositumomab, with little consideration for its potential intrinsic therapeutic activity.58 Only an extremely limited amount of patient data are available for unlabeled B1, acquired as part of a study to measure the contributions of the mAbs and the targeted radioisotope in the therapeutic activity of radioiodinated B1.59 Interestingly, the results show that, even as a “naked” mAb, B1 is capable of inducing objective responses in NHL patients, including a number of complete responses. Thus, although the study also showed that B1 generated a number of human anti–mouse antibody responses, it indicated a surprising level of activity for a rodent mAb. For the future, a humanized version of B1 might be an interesting reagent for development, since it should have many of the beneficial properties of Ritux, including the ability to induce ADCC29,60 and apoptosis7,8,29,60 (and M.S.C. et al., unpublished results, June 2001), but might avoid some of the adverse toxic activity that arises when Ritux activates complement.14

We wish to express our gratitude to all members of the Tenovus Cancer Laboratory who provided expert technical support and valuable discussion. We are also indebted to Drs Richard Miller, Geoff Hale, and Fabio Malavasi for generously providing mAbs. We wish to thank Mr Roger Alston (Biomedical Imaging Unit) for assistance with confocal microscopy.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 19, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1761.

Supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), Tenovus of Cardiff, Cancer Research United Kingdom, and the Leukaemia Research Fund.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Martin J. Glennie, Tenovus Laboratory, Cancer Sciences Division, General Hospital, Southampton, SO16 6YD, United Kingdom; e-mail: mjg@soton.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal