p16 and p15, 2 inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases, are frequently hypermethylated in hematologic neoplasias. Decitabine, or 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine, reverts hypermethylation of these genes in vitro, and low-dose decitabine treatment improves cytopenias and blast excess in ∼50% of patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). We examined p15and p16 methylation status in bone marrow mononuclear cells from patients with high-risk MDS during treatment with decitabine, using a methylation-sensitive primer extension assay (Ms-SNuPE) to quantitate methylation, and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and bisulfite-DNA sequencing to distinguish individually methylated alleles. p15 expression was serially examined in bone marrow biopsies by immunohistochemistry. Hypermethylation in the 5′ p15 gene region was detected in 15 of 23 patients (65%), whereas the 5′ p16 region was unmethylated in all patients. Among 12 patients with hypermethylation sequentially analyzed after at least one course of decitabine treatment, a decrease in p15 methylation occurred in 9 and was associated with clinical response. DGGE and sequence analyses were indicative of hypomethylation induction at individual alleles. Immunohistochemical staining for p15 protein in bone marrow biopsies from 8 patients with p15 hypermethylation revealed low or absent expression in 4 patients, which was induced to normal levels during decitabine treatment. In conclusion, frequent, selectivep15 hypermethylation was reversed in responding MDS patients following treatment with a methylation inhibitor. The emergence of partially demethylated epigenotypes and re-establishment of normal p15 protein expression following the initial decitabine courses implicate pharmacologic demethylation as a possible mechanism resulting in hematologic response in MDS.

Introduction

The 5-methylcytosine distribution patterns in DNA are frequently altered during cellular transformation.1CpG island hypermethylation can coexist with global or gene-specific demethylation in malignant cells,2-5 resulting in transcriptional inactivation (“silencing”) if it occurs in a promoter region. Expression of tumor suppressor genes (TSG) containing CpG-rich islands can be down-regulated by de novo methylation in primary tumors in vivo.1 5-7 Several TSGs altered by hypermethylation encode genes involved in cell cycle regulation (eg, Rb, p16, p15, VHL). Inactivation of TSGs by hypermethylation thus provides a novel therapeutic opportunity based on restoration of gene function and growth control in malignant cells by induction of demethylation.

5-Azacytidine and 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine), 2 potent inhibitors of cytosine methylation,8 have shown strong antileukemic activity9 in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In addition, both induce trilineage responses in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) at dose levels allowing for outpatient management, with moderate myelotoxicity and no significant nonhematologic toxicity. In a recent report of a clinical phase 3 study, 5-Azacytidine altered the natural course of MDS.10 Decitabine results in a 49% to 53% hematologic and a 31% cytogenetic response rate in high-risk MDS.11-13 Activity of demethylating agents in myeloid malignancies may hypothetically be due to induction of differentiation,14 cytotoxicity,15 or changes in the rate of apoptosis. Conceivably, these pathways could be triggered by up-regulation of eg, growth-control genes silenced via hypermethylation.

p15, a target of transforming growth factor-β signaling,16 is an inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinase-417,18 and a negative regulator of the G1/S progression within the cell cycle.19p15 is highly homologous to and colocalized withp16 within a ∼25-kb region on the short arm of human chromosome 9. Unlike in solid tumors, the 5′ region of p15but not p16 is frequently methylated in AML5,7and MDS.20,21 Selective p15 hypermethylation was also observed in a mouse model of radiation-induced malignant lymphoma.22 23 To determine whether the hypermethylated 5′ region of p15 was demethylated in MDS patients undergoing low-dose decitabine treatment, we examined it in 23 patients.

A methylation-sensitive single nucleotide primer extension (Ms-SNuPE) assay was used, since it is quantitative even when measuring a low degree of methylation.24 25 To address whether partially demethylated epigenotypes are newly generated during treatment (indicative of allele-specific hypomethylation), denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and sequence analyses were performed. Immunohistochemistry for p15 protein was performed on bone marrow cells with p15 hypermethylation. Reversal of p15hypermethylation in responding MDS patients was associated with partially demethylated epigenotypes and induction of p15re-expression. Hypermethylated p15 (and other methylated genes) may be a therapeutic target of the DNA methylation-inhibitory activity of decitabine in MDS.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient samples

Bone marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs) were collected from MDS patients before and during treatment with decitabine (kindly provided by Pharmachemie B.V., Haarlem, The Netherlands) within a phase 2 study12 approved by the local ethics committee, after obtaining informed written consent. Samples from 23 patients (10 men and 13 women, median age, 65 years; range, 52-80 years) were analyzed prior to treatment and when bone marrow studies were done according to study protocol or clinical course. Control samples included peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) and bone marrow MNCs from healthy donors, CD34+-enriched normal peripheral blood progenitor cells from patients with breast cancer, leukemic blasts from a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), and sperm DNA.

Hematologic responses of the decitabine-treated MDS patients were defined as described12: complete remission was defined as a normocellular or slightly hypocellular marrow with fewer than 5% blasts and hemoglobin (Hb) level higher than 11 g/dL; granulocyte numbers higher than 1.0 × 109/L; and platelet count greater than 100 × 109/L. Partial remission was defined as a greater than 50% decrease in the number of bone marrow myeloblasts and a trilineage response (increase in Hb level by more than 2 g/dL, in platelet count by more than 50 × 109/L, and in granulocyte count by more than 1.0 × 109/L). Hematologic improvement was defined as an improvement of 1 to 3 lineages of the peripheral cell counts but not enough to qualify for a partial remission.12 Blast reduction was defined by at least a 20% reduction relative to the initial bone marrow blast count in case of blast excess. Stable disease was defined by the absence of complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR), hematologic improvement, or blast reduction but without clear disease progression.

Ms-SNuPE analysis

Two micrograms of DNA (isolated using standard protocols) was digested with EcoRI (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) and treated with sodium bisulfite for 16 hours as described.26 Methylation analysis was performed using the methylation-sensitive single nucleotide primer extension (Ms-SNuPE) assay.24,27 Primers have been described.27Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for the p15 andp16 promoters were performed in 25 μL total volume under conditions described previously.27 PCR products were gel-purified (QiaQuick; Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and the template was resuspended in 20 to 40 μL volume of H2O. Ms-SNuPE reactions were performed in a 10 μL volume, and 50 to 100 ng of DNA was incubated in a final concentration of 1 × PCR buffer, 1 μM of each Ms-SNuPE primer, and 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) of either [32P]dCTP or [32P]dTTP. One unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) complexed with Taq polymerase antibody (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA) in a 1:1 ratio was used in the PCR reaction. Primer extension conditions were 95°C for 2 minutes, 46.5°C for 2 minutes, and 72°C for 1minute. Using a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (7 M urea), a band in the C lane resulting from the Ms-SNuPE labeling represents the amount of methylated cytosines (signal from quantitative incorporation of [32P]dCTP), while a band in the T lane is the product of [32P]dTTP incorporation at an unmethylated cytosine molecule at one of the 3 CpG sites examined (12-, 14-, and 17-bp bands represent the signals of the 3 oligonucleotides of respective lengths).27p15 methylation (given in percentages below the C lanes) was determined by quantifying the radioactive signal incorporated into the 3 labeled primers during the primer extension step of Ms-SNuPE. Counts were measured using a phosphorimager. The average of the 3 CpG sites was calculated, subtracted from the lane background, and expressed as a C/C + T ratio.

Bisulfite-DGGE analysis

Collective amplification of methylated and unmethylatedp15 alleles (between positions −47 and +215 relative to the transcription start site) was performed by a PCR reaction using previously described guanine-cytosine (GC)–clamped primers.28 PCR was carried out in a final volume of 25 μL containing 100 to 200 ng bisulfite-treated DNA, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM cresol red, 12% sucrose, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.4 μM each primer, and 0.8 units of AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Gaithersburg, MD). The PCR reaction was initiated by “hot start,” followed by 39 cycles at 94°C for 20 seconds, 55°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. Normal peripheral blood cells (normal PBCs) and in vitro methylated DNA served as negative and positive controls, respectively. Fifteen microliters of the PCR product was loaded onto a 10% denaturant/6% polyacrylamide-70% denaturant/12% polyacrylamide double-gradient gel (100% denaturant = 7 M urea and 40% formamide). The gel was run at 110 V for 16 hours in 1 × Tris acetate/EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) buffer at 56°C, methylated alleles migrate farther than unmethylated alleles. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV transillumination.

Bisulfite genomic sequencing

For subcloning and sequencing of individual alleles, bisulfite-treated genomic DNA was amplified with primers for the 5′ region of p15 (as described above) or exon 2 ofp16, respectively.29 Purified PCR products were subcloned using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Individual clones were grown and DNA was prepared using mini-prep kits. Up to 10 individual clones of each bisulfite preparation were subjected to automated sequencing in both directions using an ABI Sequencer (Foster City, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Serially obtained, calcium acetate glutaraldehyde formaldehyde (CGF)–fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections from 5 healthy individuals (bone marrow donors) and 10 patients withp15 hypermethylation were incubated with a polyclonal anti-p15 antibody (K-18; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) diluted 1:75 as described.303-amino-9-ethylcarbazole served as chromogen using the avidin-biotin method (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections were counterstained with Meyer hemalaun (Sigma). Staining of myeloid precursors was scored semiquantitatively by visual inspection for 3 categories: −, completely negative or only few dispersed positive cells; +, a moderate number of cells stained positive; ++, the majority or all cells stained positive.

Simultaneous detection of p15 and CD34 protein on bone marrow biopsies was achieved by double-staining with p15antibody (labeled by the avidin-biotin complex method) and human CD34 monoclonal antibody QBEND10 (Immunotech, Marseille, France) labeled by alkaline phosphatase antialkaline phosphatase (APAAP) method as described.31

Results

Hypermethylation of the p15/INK4B 5′ region is frequent in high-risk MDS

Bone marrow MNCs from 23 patients with intermediate/high-risk MDS32 were analyzed for p15 methylation prior to decitabine treatment. Three CpG nucleotides within a 170-bp region extending into p15 exon 1 and part of a CpG island were subjected to Ms-SNuPE analysis. Normal peripheral blood and bone marrow MNCs exhibit between 1% and 10% methylation of the 5′ regions ofp15 and p16.24 27 A conservative, arbitrary cutoff of 15% methylation was therefore chosen to define hypermethylation. p15 methylation of greater than 15% was observed in 15 of 23 patients (median, 29%; range, 16%-54%, Table1). Hypermethylation occurred in all French-American-British (FAB) subtypes and thus was not limited to the presence of excess bone marrow blasts. Thep16 promoter region showed minimal hypermethylation in any patient (median, 3%; range, 1%-10%).

Frequent hypermethylation of the 5′ region of p15 but not p16 in patients with MDS

| Patient . | Age/sex . | MDS subtype . | Bone marrow blasts (%) . | Cytogenetic risk . | IPSS . | 1-mCp15 (%) . | 1-mCp16 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | 72/M | CMMoL | 15 | INT | High | 48 | 4 |

| 002 | 80/M | RAEB-t | 30 | Poor | High | 10 | 5 |

| 003 | 76/F | RAEB-t | 25 | Poor | High | 27 | 6 |

| 004 | 65/F | RA | < 5 | INT | INT-1 | 27 | 3 |

| 005 | 64/M | RAEB | 8 | INT | INT-2 | 35 | 1 |

| 006 | 73/M | CMMoL | 2 | NN | INT-1 | 28 | 8 |

| 007 | 75/F | RAEB-t | 25-30* | Poor | High | 48 | 2 |

| 008 | 64/M | RAEB-t | 30 | INT | High | 29 | 3 |

| 009 | 64/M | RAEB-t | 21 | NN | High | 12 | 1 |

| 010 | 55/F | RA | < 5 | Poor | INT-2 | 27 | 10 |

| 011 | 78/M | RA | < 5 | Good | INT-1 | 4 | 1 |

| 012 | 75/F | RAEB | 15 | INT | INT-2 | 32 | 1 |

| 013 | 72/F | RAEB | 20 | Poor | High | 27 | ND |

| 014 | 61/F | RA | < 5 | NN | INT-1 | 16 | 2 |

| 015 | 52/F | RAEB | 9 | NN | INT-1 | 8 | 4 |

| 016 | 64/M | RAEB-t | 30 | Poor | High | 45 | 8 |

| 017 | 64/M | CMMoL | < 5 | NN | INT-1 | 5 | 1 |

| 018 | 62/F | sAML | 60 | Poor | — | 54 | 4 |

| 019 | 62/F | RAEB | 20 | INT | High | 28 | 1 |

| 020 | 69/F | RAEB-t | 24 | NN | High | 10 | 9 |

| 021 | 61/M | RAEB-t | 28 | Poor | High | 13 | 1 |

| 022 | 78/F | sAML | 41 | ND | — | 42 | ND |

| 023 | 34/F | RA | < 5 | Poor | INT-2 | 7 | ND |

| Patient . | Age/sex . | MDS subtype . | Bone marrow blasts (%) . | Cytogenetic risk . | IPSS . | 1-mCp15 (%) . | 1-mCp16 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | 72/M | CMMoL | 15 | INT | High | 48 | 4 |

| 002 | 80/M | RAEB-t | 30 | Poor | High | 10 | 5 |

| 003 | 76/F | RAEB-t | 25 | Poor | High | 27 | 6 |

| 004 | 65/F | RA | < 5 | INT | INT-1 | 27 | 3 |

| 005 | 64/M | RAEB | 8 | INT | INT-2 | 35 | 1 |

| 006 | 73/M | CMMoL | 2 | NN | INT-1 | 28 | 8 |

| 007 | 75/F | RAEB-t | 25-30* | Poor | High | 48 | 2 |

| 008 | 64/M | RAEB-t | 30 | INT | High | 29 | 3 |

| 009 | 64/M | RAEB-t | 21 | NN | High | 12 | 1 |

| 010 | 55/F | RA | < 5 | Poor | INT-2 | 27 | 10 |

| 011 | 78/M | RA | < 5 | Good | INT-1 | 4 | 1 |

| 012 | 75/F | RAEB | 15 | INT | INT-2 | 32 | 1 |

| 013 | 72/F | RAEB | 20 | Poor | High | 27 | ND |

| 014 | 61/F | RA | < 5 | NN | INT-1 | 16 | 2 |

| 015 | 52/F | RAEB | 9 | NN | INT-1 | 8 | 4 |

| 016 | 64/M | RAEB-t | 30 | Poor | High | 45 | 8 |

| 017 | 64/M | CMMoL | < 5 | NN | INT-1 | 5 | 1 |

| 018 | 62/F | sAML | 60 | Poor | — | 54 | 4 |

| 019 | 62/F | RAEB | 20 | INT | High | 28 | 1 |

| 020 | 69/F | RAEB-t | 24 | NN | High | 10 | 9 |

| 021 | 61/M | RAEB-t | 28 | Poor | High | 13 | 1 |

| 022 | 78/F | sAML | 41 | ND | — | 42 | ND |

| 023 | 34/F | RA | < 5 | Poor | INT-2 | 7 | ND |

Methylation of both 5′ regions was measured by Ms-SNuPE as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.”

MDS subtypes: RA indicates refractory anemia; RAEB, refractory anemia with excess of blasts; RAEB-t, refractory anemia with excess of blasts in transformation. CMMoL indicates chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; sAML, progression to secondary acute myeloid leukemia at time of treatment start; NN, normal karyotype; cytogenetic risk, cytogenetic risk score (good: normal karyotype, −Y, del [5q], del [20q]; poor: complex [at least 3 abnormalities] or chromosome 7 anomalies; intermediate [INT]: other abnormalities); IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System32;

C (%), methylation status in percentage measured by Ms-SNuPE; ND, not determined.

Bone marrow histology.

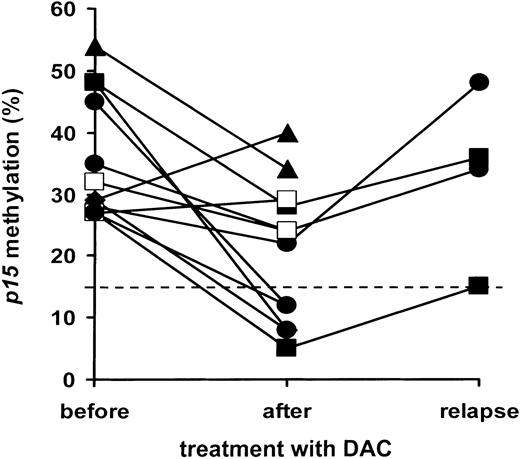

Reversal of p15 hypermethylation in MDS by decitabine treatment

Of 23 MDS patients receiving one or more courses of low-dose decitabine,12 19 were evaluable for changes inp15 methylation, 2 had disease progression prior to start, one died prior to evaluation after course 1, and one had progressive cytopenia and declined a second bone marrow aspirate. As shown for a representative patient in Figure 1, initial p15 hypermethylation (45%) was reduced to 33% following the first course of decitabine, with reduction to 12% after 3 subsequent courses. Of 12 patients with p15hypermethylation prior to decitabine treatment, 9 showed at least a 25% decrease, to a median of 16% (range, 5%-34%). In one case, the decrease was less than 25%; in 2 cases, p15 methylation increased (Figure 2). Patients without initialp15 hypermethylation showed no changes in methylation levels during continued treatment. Hematologic responses are given in Table2: p15 promoter hypermethylation was frequently reversed with response to decitabine treatment and associated with complete remissions, but was not a prerequisite for other hematologic responses (partial remission in patient 015).

Reduction of p15 hypermethylation in a patient with high-risk MDS treated with decitabine.

Ms-SNuPE analysis was performed on bone marrow MNCs of patient 016 (RAEB-t, refractory anemia with excess of blasts in transformation) before (pre), after one (DAC1) and 4 courses (DAC4) of decitabine treatment, respectively. CML-145 (peripheral blood MNCs from a patient with blast crisis CML and known p15hypermethylation27), normal peripheral blood cells (white blood cells [WBCs]), and sperm DNA served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Using a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (7 M urea), a band in the C lane resulting from the Ms-SNuPE labeling represents the amount of methylated cytosines (signal from quantitative incorporation of [32P]dCTP), while a band in the T lane is the product of [32P]dTTP incorporation at an unmethylated cytosine molecule at one of the 3 CpG sites examined (12-, 14-, and 17-bp bands represent the signals of the 3 oligonucleotides of respective lengths).27p15methylation (given in percentages below the C lanes) was determined by quantifying the radioactive signal incorporated into the 3 labeled primers during the primer-extension step of Ms-SNuPE. Counts were measured using a phosphorimager. The average of all 3 CpG sites was calculated, subtracted from the lane background, and expressed as a C/C + T ratio as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.”

Reduction of p15 hypermethylation in a patient with high-risk MDS treated with decitabine.

Ms-SNuPE analysis was performed on bone marrow MNCs of patient 016 (RAEB-t, refractory anemia with excess of blasts in transformation) before (pre), after one (DAC1) and 4 courses (DAC4) of decitabine treatment, respectively. CML-145 (peripheral blood MNCs from a patient with blast crisis CML and known p15hypermethylation27), normal peripheral blood cells (white blood cells [WBCs]), and sperm DNA served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Using a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (7 M urea), a band in the C lane resulting from the Ms-SNuPE labeling represents the amount of methylated cytosines (signal from quantitative incorporation of [32P]dCTP), while a band in the T lane is the product of [32P]dTTP incorporation at an unmethylated cytosine molecule at one of the 3 CpG sites examined (12-, 14-, and 17-bp bands represent the signals of the 3 oligonucleotides of respective lengths).27p15methylation (given in percentages below the C lanes) was determined by quantifying the radioactive signal incorporated into the 3 labeled primers during the primer-extension step of Ms-SNuPE. Counts were measured using a phosphorimager. The average of all 3 CpG sites was calculated, subtracted from the lane background, and expressed as a C/C + T ratio as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.”

p15 methylation changes in MDS during treatment with decitabine.

p15 methylation (averaged and given as percentage as described in legend to Figure 1) was plotted before and after treatment with decitabine, as well as at relapse for some patients. Results of treatment courses are plotted separately for 12 patients with initialp15 methylation of more than 15% (A). Methylation as determined after ■, 1 course of decitabine; ▴, 2 courses of decitabine; ▪, 3 courses of decitabine; ●, 4 to 6 courses of decitabine (where possible at evaluation of the final course).

p15 methylation changes in MDS during treatment with decitabine.

p15 methylation (averaged and given as percentage as described in legend to Figure 1) was plotted before and after treatment with decitabine, as well as at relapse for some patients. Results of treatment courses are plotted separately for 12 patients with initialp15 methylation of more than 15% (A). Methylation as determined after ■, 1 course of decitabine; ▴, 2 courses of decitabine; ▪, 3 courses of decitabine; ●, 4 to 6 courses of decitabine (where possible at evaluation of the final course).

Reversal of p15 hypermethylation and hematologic response of high-risk MDS patients after decitabine treatment

| Patient . | HypermC reversal . | Hematologic response . | DAC courses . | Survival (mo) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | Yes | Blast reduction, hematologic improvement | 6 | 27 |

| 002 | NM | Progression to AML | 4 | 7 |

| 003 | Yes | Complete remission | 5 | 16 |

| 004 | ND | Progressive cytopenia | 1 | 50 |

| 005 | Yes | Blast reduction | 4 | 15 |

| 006 | Yes | Hematologic improvement | 4 | 15 |

| 007 | Yes | Complete remission | 4 | 13 |

| 008 | No | Progression to AML | 1 | 11 |

| 009 | NM | Blast reduction, hematologic improvement | 4 | 31 |

| 010 | No | Progressive cytopenia | 1 | 10 |

| 011 | NM | Hematologic improvement | 2 | 38 |

| 012 | No | Progression to AML | 1 | 1 |

| 013 | Yes | Complete remission | 4 | 21 |

| 014 | ND | Toxic death | 1 | 2 |

| 015 | NM | Partial remission | 6 | 18 |

| 016 | Yes | Blast reduction, tril hematologic improvement | 6 | 44 |

| 017 | NM | Stable disease | 2 | 52 |

| 018 | Yes | Blast reduction | 2 | 5 |

| 019 | Yes | Blast reduction, hematologic improvement | 6 | 73 |

| 020 | NM | Blast reduction, hematologic improvement | 6 | 75 |

| 021 | NM | Progression to AML | 1 | 5 |

| 022 | ND | No decitabine treatment | — | 2 |

| 023 | ND | No decitabine treatment | — | 32+ |

| Patient . | HypermC reversal . | Hematologic response . | DAC courses . | Survival (mo) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | Yes | Blast reduction, hematologic improvement | 6 | 27 |

| 002 | NM | Progression to AML | 4 | 7 |

| 003 | Yes | Complete remission | 5 | 16 |

| 004 | ND | Progressive cytopenia | 1 | 50 |

| 005 | Yes | Blast reduction | 4 | 15 |

| 006 | Yes | Hematologic improvement | 4 | 15 |

| 007 | Yes | Complete remission | 4 | 13 |

| 008 | No | Progression to AML | 1 | 11 |

| 009 | NM | Blast reduction, hematologic improvement | 4 | 31 |

| 010 | No | Progressive cytopenia | 1 | 10 |

| 011 | NM | Hematologic improvement | 2 | 38 |

| 012 | No | Progression to AML | 1 | 1 |

| 013 | Yes | Complete remission | 4 | 21 |

| 014 | ND | Toxic death | 1 | 2 |

| 015 | NM | Partial remission | 6 | 18 |

| 016 | Yes | Blast reduction, tril hematologic improvement | 6 | 44 |

| 017 | NM | Stable disease | 2 | 52 |

| 018 | Yes | Blast reduction | 2 | 5 |

| 019 | Yes | Blast reduction, hematologic improvement | 6 | 73 |

| 020 | NM | Blast reduction, hematologic improvement | 6 | 75 |

| 021 | NM | Progression to AML | 1 | 5 |

| 022 | ND | No decitabine treatment | — | 2 |

| 023 | ND | No decitabine treatment | — | 32+ |

Reversal of p15 hypermethylation was defined as at least 25% reduction of methylation (relative to hypermethylation of more than 15% prior to treatment as given in Table 1). Thus, for the 7 patients with initial methylation of no more than 15%, reversal of hypermethylation was not measurable (NM). The total number of courses administered is given. Hematologic responses were defined as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.”12 Survival (in months) was from start of decitabine treatment (patients 001-021) or from diagnosis (patients 022, 023). For patient 001 at relapse and patient 018 during progression, p15 methylation was determined from peripheral blood MNCs because bone marrow MNCs were not available. ND indicates not done; —, no decitabine treatment; hematologic response not given because of early progression to AML (patient 022) and allogeneic transplantation as first line therapy (patient 023). Follow-up was until August 1, 2001.

Decitabine induces changes in the distribution of hypermethylated p15 epigenotypes in vivo

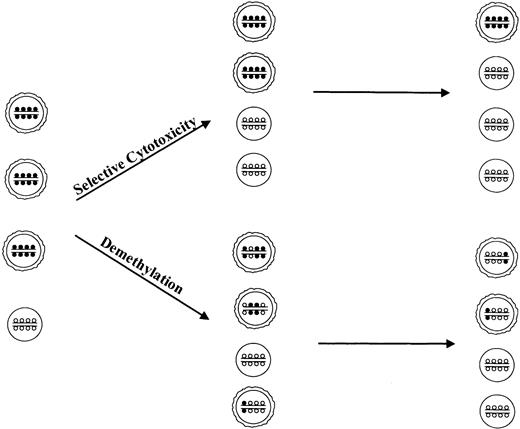

At the estimated steady-state serum levels of 0.1 to 0.5 μM decitabine,33-35 demethylation of several genes occurs in vitro5,23,36-38 and in rodent models.38 Bulkp15 demethylation during decitabine treatment may reflect emergence of normal hematopoietic progenitors with suppression of clonal cells, reduction of methylation in hypermethylatedp15 alleles of clonal cells (depicted schematically in Figure 3), or a combination of both. Thus, 2 general mechanisms of action may be hypothesized: blast removal by selective cytotoxicity results in a reduction of the dysplastic clone and allows expansion of normal bone marrow precursor cells (Figure 3, upper panel); or inhibition of maintenance methylation during each cell division leads to progressive exchange of methylcytosines for cytosines at individual alleles and, after several cell divisions, to a decrease in cells with highly methylated alleles and to expansion of normal hematopoietic cells (Figure 3, lower panel).

Possible mechanisms of action of methylation inhibitors in MDS.

Single circle indicates normal hematopoetic precursor bone marrow cells; 2 circles, cells from myelodysplastic clone; small open circles, cytosine; small closed circles, methylcytosine.

Possible mechanisms of action of methylation inhibitors in MDS.

Single circle indicates normal hematopoetic precursor bone marrow cells; 2 circles, cells from myelodysplastic clone; small open circles, cytosine; small closed circles, methylcytosine.

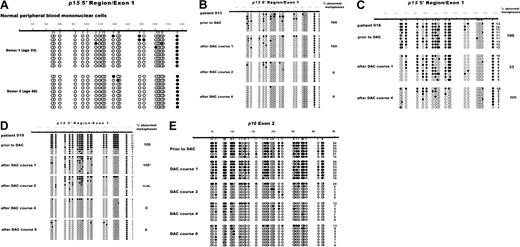

Individual, clonotypic p15 epigenotypes can be detected by DGGE: migration distances of unmethylated, fully methylated, and partially methylated alleles differ with differences in melting temperatures.28 Methylation at 27 CpG residues in a region of the 5′ p15 gene that is nonoverlapping with the Ms-SNuPE amplicon was examined in bone marrow cells from 7 patients withp15 hypermethylation. Normal hematopoietic cells (bone marrow MNCs, CD34+-enriched peripheral blood progenitor cells [PBPCs], PBL) served as negative controls. Hypermethylation was observed in 6 of 7 MDS patients (ie, 87% concordance between DGGE and Ms-SNuPE). In 4 cases, distinct bands indicative of several partially methylated epigenotypes were detectable (shown for 2 patients in Figure 4). In the remaining 2 patients, hypermethylation appeared as an indistinct smear (not shown), similar to the heterogenous pattern of multiple epigenotypes described in AML.28 Cells from patient 019 (panel A) and patient 013 (panel B) prior to treatment had diminished intensity of the top band (representing unmethylated alleles), compared to PBL control, and multiple bands representing partially methylated alleles. Following one course of treatment, this pattern was clearly altered, with novel, distinct bands closer to the top band, without significant reduction in bone marrow blast percentage. After 2 and more courses of treatment, the top band indicating unmethylatedp15 alleles predominated, and blast suppression occurred. These results are indicative of novel, partly demethylated epigenotypes being generated during the initial treatment courses of decitabine.

Methylation changes of the 5′ p15 gene during decitabine treatment visualized by DGGE.

(A) Bone marrow cells of patient 019 before and after courses 1, 2, and 6 of DAC treatment were analyzed by DGGE as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” The PCR reaction was initiated by “hot start,” followed by 39 cycles at 94°C for 20 seconds, 55°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. Normal PBCs and in vitro methylated DNA served as negative and positive controls, respectively. Methylated alleles migrate farther than unmethylated alleles. The percentage of bone marrow blasts (relative to the nonerythroid cell fraction) is given below each lane. (B) Bone marrow cells of patient 013 before treatment and after courses 1 and 2 were analyzed by DGGE as described above.

Methylation changes of the 5′ p15 gene during decitabine treatment visualized by DGGE.

(A) Bone marrow cells of patient 019 before and after courses 1, 2, and 6 of DAC treatment were analyzed by DGGE as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” The PCR reaction was initiated by “hot start,” followed by 39 cycles at 94°C for 20 seconds, 55°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. Normal PBCs and in vitro methylated DNA served as negative and positive controls, respectively. Methylated alleles migrate farther than unmethylated alleles. The percentage of bone marrow blasts (relative to the nonerythroid cell fraction) is given below each lane. (B) Bone marrow cells of patient 013 before treatment and after courses 1 and 2 were analyzed by DGGE as described above.

Clonal analysis of variably methylated alleles by bisulfite DNA sequencing

Clonal analysis of MDS cells by culturing in semisolid media is often hampered by their low clonogenicity. To perform a clonal analysis not of cells but of single DNA molecules, individual p15alleles from 3 MDS patients with informative chromosomal abnormalities and from 2 healthy individuals were subcloned and sequenced following PCR amplification of bisulfite-treated DNA.

In the 2 healthy individuals, the 5′ region of p15 was almost completely unmethylated in all alleles except for a single CpG in the 3′ end of the cloned molecules, which was almost always methylated (Figure 5A). Individualp15 alleles of 3 MDS patients analyzed before decitabine treatment revealed a variable degree of methylated CpGs relative to all CpGs sequenced, averaging from 20% (patient 013, Figure 5B, upper rows) to 61% (patient 016, Figure 5C) and 76% (patient 019, Figure5D). In each patient, the percentage of methylated moieties in individual alleles was reduced after the first course of decitabine treatment, to 10%, 39%, and 22%, respectively. At evaluation after 4 courses (patient 013, 016) and 6 courses (patient 019), methylation patterns in most or all alleles analyzed were identical to those of healthy individuals. Metaphase cytogenetics done at different treatment points revealed 100% abnormal metaphases before treatment in each patient. These were replaced by 100% (patient 013, 019) normal metaphases at the last time point analyzed (Figure 5B-D, bottom rows). Persistence of abnormal metaphases (100% in patient 013 and 019, 33% in patient 016) was noted after the first treatment course, when partially demethylated alleles were first detectable.

Variable hypermethylation of individual p15 alleles is reduced by repeated courses of decitabine.

Analysis of p15 (5′ region, A-D) and p16(exon 2, E) methylation status was determined by sequencing of individual alleles subcloned from bisulfite-treated, PCR-amplified DNA. Normal peripheral blood cells of 2 healthy individuals (A) and bone marrow MNCs from MDS patients 013 (B), 016 (C), and 019 (D,E) were analyzed. Each row represents a single cloned allele. ○, nonmethylated CpG; ●, methylated CpG. Numbering of nucleotides is according to published sequences. Count of methylated CpGs is given for each clone. Bone marrow aspirates for evaluation of hematologic and cytogenetic response were performed between 5 and 8 weeks (median, 6 weeks) after a treatment course. Percent of abnormal metaphases are given on the right. Metaphase cytogenetics were performed as described elsewhere.13 *Cytogenetics were performed on a second aspirate done 47 days later. nm, no metaphases obtained due to lack of dividing cells.

Variable hypermethylation of individual p15 alleles is reduced by repeated courses of decitabine.

Analysis of p15 (5′ region, A-D) and p16(exon 2, E) methylation status was determined by sequencing of individual alleles subcloned from bisulfite-treated, PCR-amplified DNA. Normal peripheral blood cells of 2 healthy individuals (A) and bone marrow MNCs from MDS patients 013 (B), 016 (C), and 019 (D,E) were analyzed. Each row represents a single cloned allele. ○, nonmethylated CpG; ●, methylated CpG. Numbering of nucleotides is according to published sequences. Count of methylated CpGs is given for each clone. Bone marrow aspirates for evaluation of hematologic and cytogenetic response were performed between 5 and 8 weeks (median, 6 weeks) after a treatment course. Percent of abnormal metaphases are given on the right. Metaphase cytogenetics were performed as described elsewhere.13 *Cytogenetics were performed on a second aspirate done 47 days later. nm, no metaphases obtained due to lack of dividing cells.

A comparative analysis was also performed on the p16 3′ coding region. This region has been shown to both remethylate more readily than the p16 promoter region in vitro39 and to be methylated to a variable degree in cells from leukemia patients.29 A comparison of fully versus partially methylated alleles of p15 (Figure 5D) and p16exon 2 (Figure 5E) after one course of treatment showed partial demethylation in the p15 5′ region but not in the p16exon 2 region of patient 019, also implying cytosine demethylation at individual alleles.

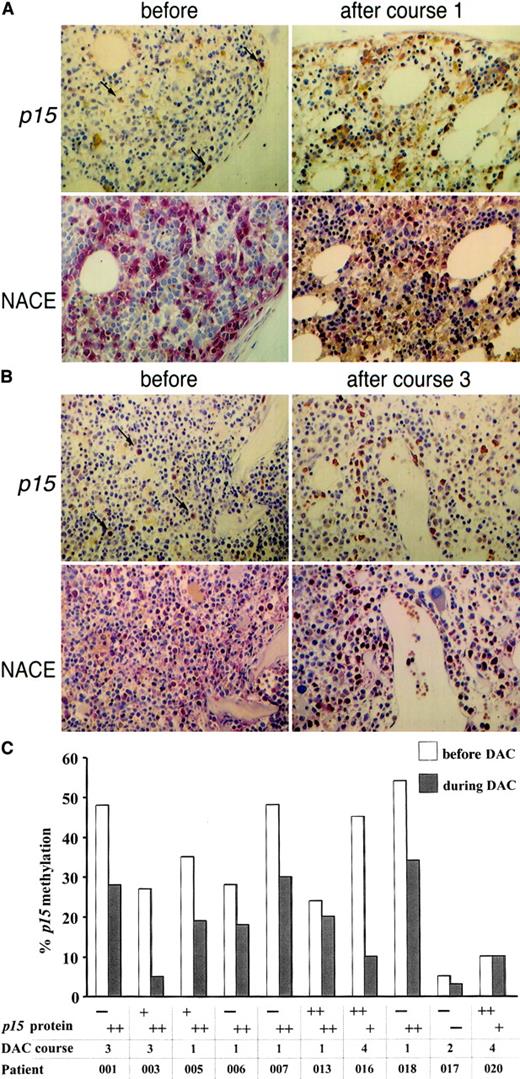

p15 expression is induced in myeloid precursor cells during decitabine treatment

p15 hypermethylation is frequently associated with reduced or absent p15 expression in leukemic cells and cell lines.23,40-43 We examined p15 expression immunohistochemically in fixed-trephine bone marrow biopsies. Among 5 healthy individuals, p15 positivity was scored in the majority of cells in 3 and in a moderate number of cells in 2. As previously described,30 cytoplasmic p15 protein was predominantly detected in granulocyte precursor cells but not in erythroid cells and megakaryocytes (data not shown). p15staining was then performed on serial biopsies from 10 MDS patients (shown for 2 patients in Figure 6A-B). In 4 of 8 cases with p15 hypermethylation, cytoplasmicp15 expression was very low or absent prior to treatment, whereas in the other 4 patients and in 2 patients without hypermethylation, p15 levels were comparable to normal bone marrow (Figure 6C). Following 1 to 3 courses of decitabine,p15 expression was induced to high levels in all 4 patients with initially low or absent expression and persisted in the 6 patients with p15 expression prior to decitabine. Expression was restricted to granulocyte precursor cells, and their abundance in the bone marrow did not change significantly with treatment (Figure 6A-B). Serial cytogenetics revealed persistence of the chromosomal abnormalities in all metaphases from patients 001, 005, and 018 with induction of p15 expression, suggesting that bothp15 methylation and expression were altered in the same clone.

p15 protein expression in MDS bone marrow cells is up-regulated with p15 demethylation during decitabine treatment.

(A) Bone marrow biopsy from patient 006 before (left) and after (right) 1 course of treatment; magnification, × 40. Upper panel:p15 staining; lower panel: granulocytes and precursors detected by naphthol AS-D-chloroacetate esterase (NACE) staining. Arrows indicate p15 staining in isolated cells prior to treatment. (B) Patient 001 before (left) and after (right) 3 courses of treatment. Immunohistochemical staining of myeloid precursors was scored semiquantitatively by visual inspection for 3 categories: −, completely negative or only few dispersed positive cells; +, a moderate number of cells stained positive; ++, the majority or all cells stained positive. (C) 8 patients with p15 hypermethylation (> 15%) were examined for p15 expression prior to treatment (white columns) and at time of maximal hypomethylation (gray columns) and 2 patients with p15 methylation lower than 15%. An abnormal karyotype was present prior to treatment in all patients except 006, 017, and 020. Complete reversion to normal karyotype at time of maximal hypomethylation (gray columns, course number given below) occurred only in patient 003.

p15 protein expression in MDS bone marrow cells is up-regulated with p15 demethylation during decitabine treatment.

(A) Bone marrow biopsy from patient 006 before (left) and after (right) 1 course of treatment; magnification, × 40. Upper panel:p15 staining; lower panel: granulocytes and precursors detected by naphthol AS-D-chloroacetate esterase (NACE) staining. Arrows indicate p15 staining in isolated cells prior to treatment. (B) Patient 001 before (left) and after (right) 3 courses of treatment. Immunohistochemical staining of myeloid precursors was scored semiquantitatively by visual inspection for 3 categories: −, completely negative or only few dispersed positive cells; +, a moderate number of cells stained positive; ++, the majority or all cells stained positive. (C) 8 patients with p15 hypermethylation (> 15%) were examined for p15 expression prior to treatment (white columns) and at time of maximal hypomethylation (gray columns) and 2 patients with p15 methylation lower than 15%. An abnormal karyotype was present prior to treatment in all patients except 006, 017, and 020. Complete reversion to normal karyotype at time of maximal hypomethylation (gray columns, course number given below) occurred only in patient 003.

To address whether CD34+ blasts show changes inp15 expression during treatment, double-staining of bone marrow biopsies against p15 and CD34 was done in 3 patients with excess of CD34+ blasts. In each case, the majority of CD34+ cells were negative for p15 (data not shown). This pattern did not change in sequential biopsies from 2 patients after 1 and 3 courses of decitabine (DAC), respectively, which had both persistence of CD34 cells and up-regulation of p15, indicating that p15 is not expressed by CD34+ blasts but in more mature myeloid elements.

Discussion

Silencing of proliferation-associated genes by aberrant hypermethylation is commonly found in neoplasia. Reversion ofp16 hypermethylation by 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine results in decreased proliferation and tumorigenicity of tumor cell lines and in animal models.5,23,38,39 Therefore, clinical application of DNA methylation inhibitors such as decitabine and 5-Azacytidine may influence gene-specific hypermethylation in vivo. We asked whether the clinical activity of decitabine in MDS was associated with DNA demethylation and reversal of silencing of thep15 gene, an inhibitor of G1/S progression.18,19 The choice of p15 was prompted by recent reports describing a greater than 50% incidence of hypermethylation in the 5′ flanking region of p15 in MDS20,21 and AML,5,23,28,41 with decreased or absent p15 mRNA expression in 50% to 70% of primary AML samples.42 43

The present analysis confirmed hypermethylation of p15upstream sequences in the majority of MDS patients, which was absent in normal hematopoietic precursor and mature cells, implying thatp15 hypermethylation did not merely reflect an early maturation stage of the cells. Our results with 3 different methylation detection assays implicate 5′ methylation of p15as a regional43 rather than site-specific phenomenon. The recruitment of corepressors and histone deacetylases to stretches of densely methylated sequences by MeCP244 45 offers an explanation for the effect of a densely methylated CpG-rich regulatory region upon transcription.

Reversal of p15 hypermethylation was observed in 9 of 12 patients treated with decitabine and was associated with hematologic responses (including 3 CRs) in all 9 patients. Hematologic responses including one PR were seen in 4 of 7 patients lacking p15hypermethylation, implying that other mechanisms may have been operative. Previous studies using other methylation assays described a close association between the percentage of bone marrow blasts in MDS and p15 hypermethylation.20 21 Since we determined the p15 methylation status in unsorted bone marrow MNCs, excess blasts might be the major source of hypermethylatedp15 moieties. However, hypermethylation was also detectable in 4 of 7 patients with fewer than 5% bone marrow blasts (Table 1) and in peripheral blood MNCs not containing blasts (data not shown), suggesting that p15 methylation may be an early event preceding manifest blast expansion in MDS.

Kinetics of p15 methylation and blast percentage in the bone marrow during treatment showed emergence of fewer methylated alleles despite the persistence of blast excess and cytogenetic abnormalities. DGGE and direct sequencing of cloned molecules were indicative of induction of partial demethylation at individual alleles, as was lack of p16 exonic demethylation (Figure 5E). In 2 elegant studies also addressing the longstanding issue of pharmacological demethylation versus selection of methylated cells through cytotoxicity, increased globin expression in erythroid cells induced by 5-Azacytidine treatment was demonstrated on single erythroid colonies46 and by in situ hybridization,47respectively. In the present study, immunohistochemistry was performed on serially obtained bone marrow biopsies with p15hypermethylation. In 4 of 8 patients, abnormally low or absentp15 expression prior to treatment was up-regulated to levels found in normal bone marrow after 1 to 3 courses of decitabine and was paralleled by hypomethylation. Persistence of chromosomal markers provided further indication that demethylation occurred in cells of the abnormal clone and did not merely reflect emergence of nonclonal hematopoietic cells. Another study also described lack ofp15 expression in the majority of clonal leukemic cells in the presence of high-density p15 methylation43; however, p15 expression despite methylation of most alleles was also noted and discussed. The observed emergence of hypomethylated alleles with concurrent up-regulation of p15 expression in bone marrow cells provides the first example of gene-specific action of a demethylating antineoplastic agent in the clinical setting. However, demethylation of p15 (and other genes) during treatment with these agents does not necessarily mean that this is the main mechanism of action of this drug in vivo.

Nyce48 investigated drug-induced DNA methylation changes using several antileukemic agents. In vitro exposure (adenocarcinoma cells [HTB-54] and human rhabdomyosarcoma cells [CCI-136], human T lymphocytes [MOLT-4]) to topoisomerase II inhibitors, microtubule inhibitors, antimetabolites, hydroxyurea and 6-thioguanin, and in vivo (cytarabine and hydroxyurea) treatment resulted not in demethylation but hypermethylation of DNA. Drug-induced DNA hypermethylation could be blocked by pre-exposure to hypomethylating agents administered at nontoxic to mildly toxic concentrations.48

Acute leukemias40,49 and colorectal carcinomas50 frequently exhibit a methylator phenotype at multiple genomic loci. p15 is both informative for this phenotype in AML40,42 and a plausible candidate target for the action of DNA methylation inhibitors, since re-establishment of its inducible expression may reasonably be expected to restore control of blast proliferation in MDS. Prospective analysis of a larger patient series is necessary to determine if in MDS a methylator phenotype is predictive for complete response to methylation inhibitors. Sincep15 is unlikely to be the only hypermethylated gene in MDS, establishing other molecular targets of the pharmacologic action of these drugs is important. Their clinical application may not be limited to myeloid neoplasias, and even lower doses may still have demethylating activity. Thus, studies identifying other genes51 that are hypermethylated in MDS and targeted by demethylating agents are warranted.

Supported by Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (grant 99.032.1), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant Lu 429/5-1), and Deutscher Verein zur Förderung der Leukämie-und Tumorforschung e.V.

M.D., T.T.N., and C.N. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Michael Lübbert, Department of Hematology/Oncology, University of Freiburg Medical Center, Hugstetter Str 55, D-79106 Freiburg, Germany; e-mail:luebbert@mm11.ukl.uni-freiburg.de.

![Fig. 1. Reduction of p15 hypermethylation in a patient with high-risk MDS treated with decitabine. / Ms-SNuPE analysis was performed on bone marrow MNCs of patient 016 (RAEB-t, refractory anemia with excess of blasts in transformation) before (pre), after one (DAC1) and 4 courses (DAC4) of decitabine treatment, respectively. CML-145 (peripheral blood MNCs from a patient with blast crisis CML and known p15hypermethylation27), normal peripheral blood cells (white blood cells [WBCs]), and sperm DNA served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Using a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (7 M urea), a band in the C lane resulting from the Ms-SNuPE labeling represents the amount of methylated cytosines (signal from quantitative incorporation of [32P]dCTP), while a band in the T lane is the product of [32P]dTTP incorporation at an unmethylated cytosine molecule at one of the 3 CpG sites examined (12-, 14-, and 17-bp bands represent the signals of the 3 oligonucleotides of respective lengths).27 p15methylation (given in percentages below the C lanes) was determined by quantifying the radioactive signal incorporated into the 3 labeled primers during the primer-extension step of Ms-SNuPE. Counts were measured using a phosphorimager. The average of all 3 CpG sites was calculated, subtracted from the lane background, and expressed as a C/C + T ratio as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.”](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/8/10.1182_blood.v100.8.2957/4/m_h82023248001.jpeg?Expires=1765912325&Signature=iQMKY3Y9vBzH4a-kf8-Y3GPPH-YMsX4wKIUlnMeOXLgm2RKM~ynUlZY50YEHUMftFIszf~b5xt8jNDvF3ReuU3k0sLKRQvg04D3mi5L-kRm42b6splI3RIX~jqqtYrfGzPuhZYq~oeLN9lDvRYTRYrd5w3mFcn8tZjXMtzNJxATNbpy2C3aRL9vNLAARACfPBWjIHq0ROVxTb8UBANuA8ZQjfJ~RctvPC3NyjjRat8vzcNXAw2myAK9-NIohofoyoLinUfOAq04L~SADzSt8DATScXnLRUHs-fqrOmRmPdQ-R6gPR1V2MniXKaPCFZX~fTB1eSkNCdQ0LZmfddxvCw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal