Platelets are formed from mature megakaryocytes (MKs) and arise from the development of long and thin cytoplasmic extensions called proplatelets. After platelet release, the senescent MKs (nucleus surrounded by some cytoplasm) undergo cell death by apoptosis. To explore the precise role of apoptosis in proplatelet formation, we grew human MKs from CD34+ cells and assessed the possible role of caspases. Proteolytic maturation of procaspase-3 and procaspase-9 was detected by immunoblots in maturing MKs as well as in proplatelet-bearing MKs and senescent MKs. Cleavage of caspase substrates such as gelsolin or poly adenosine diphosphate (ADP)–ribose polymerase (PARP) was also detected. Interestingly, activated forms of caspase-3 were detected in maturing MKs, before proplatelet formation, with a punctuate cytoplasmic distribution, whereas a diffuse staining pattern was seen in senescent and apoptotic MKs. This localized activation of caspase-3 was associated with a mitochondrial membrane permeabilization as assessed by the release of cytochrome c, suggesting an activation of the intrinsic pathway. Moreover, these MKs with localized activated caspase-3 had no detectable DNA fragmentation. In contrast, when apoptosis was induced by staurosporine, diffuse caspase activation was seen; these MKs had signs of DNA fragmentation, and no proplatelet formation occurred. The pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD.fmk as well as more specific inhibitors of caspase-3 and caspase-9 blocked proplatelet formation, whereas an inhibitor of calpeptin had no effect. Overexpression of Bcl-2 also inhibited proplatelet formation in maturing MKs. Thus, localized caspase activation is causal to proplatelet formation. We conclude that proplatelet formation is regulated by a caspase activation limited to only some cellular compartments.

Introduction

Megakaryocytopoiesis is a unique process, which leads to platelet production that has 2 unique characteristics.1 First, the megakaryocyte (MK), the direct platelet precursor, is a polyploid cell.2 This polyploidization occurs by a process called endomitosis, corresponding to nuclear endoreplication without cytokinesis.3,4 At the end of polyploidization, MKs complete their cytoplasmic maturation to finally shed platelets. Second, platelets are anucleate cells formed by the fragmentation of the MK cytoplasm.5 Until recently, platelet formation was poorly understood. It was first believed that demarcation membranes, internal membranes of the MK, determined platelet territories corresponding to future platelets, which would be liberated via cytoplasmic fragmentation.6,7 However, Radley and colleagues5,8 demonstrated that demarcation membranes were internal invaginations of the cytoplasmic membrane and rather served as a reservoir of cytoplasmic membrane permitting the extension of long pseudopods. Such cytoplasmic extensions contain all the platelet organelles including mitochondria and have been termed “proplatelets.” Using in vitro cultures in presence of thrombopoietin (TPO), it has now been clearly demonstrated that platelets are released from proplatelets,9-11 confirming a hypothesis originally formulated by Becker and De Bruyn.12Proplatelet formation requires profound changes in the organization of the cytoskeleton,10,11,13,14 which may be regulated by the nuclear factor–erythroid 2 (NF-E2) transcription factor.15 16

In vivo platelet formation does not occur directly in the marrow. MKs either entirely migrate into the circulation17 or extrude proplatelets into bone marrow sinusoids; these extensions are subsequently fragmented into platelets. After release of platelets, the MK nucleus, its envelope, and its adjacent cytoplasm usually remain in the marrow and are subsequently phagocytosed by macrophages.18 These denuded MKs have been called senescent MKs, and Zauli et al19 have suggested that senescent MKs correspond to apoptotic cells. However, the precise in vitro relationship between MK apoptosis and the proplatelet formation process is elusive. Intriguingly, in transgenic mice overexpressing Bcl-2 under the control of a hematopoietic cell–specific promoter, a 2-fold reduction in platelet numbers was found, although MK numbers remained unchanged.20 A similar observation was obtained in mice with a homozygous deletion of the proapoptotic geneBim.21 Moreover, terminal differentiation associated with loss of the nucleus (as it occurs in lens cells and keratinocytes and during erythropoiesis) might be regulated by caspases, a class of proteases usually activated during apoptosis.22-26 Caspase activation may result from the ligation of plasma membrane receptors such as CD95 (the extrinsic pathway) or from the activation of a cytosolic caspase activation complex, the apoptosome (the intrinsic pathway).27 The apoptosome is activated when cytochrome c (Cyt-c) is released from mitochondria and gains access to cytosolic apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1), which in turn activates procaspase-9. Therefore, the intrinsic pathway involves a critical Bcl-2–controlled step of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (MMP).28

In this paper, we report that proplatelet formation is the consequence of a caspase-dependent mechanism that appears to be localized in the cytoplasm.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) R-PE-HPCA2 (anti-CD34) (Becton Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France), fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC) and R-phycoerythrin (RPE) anti-CD41a mAb; R-PE anti–Bcl-2 mAb; and FITC- and R-PE-isotype controls (all from Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) were used for flow cytometry . The following Abs were used for Western blot and immunofluorescence: rabbit antiactivated caspase-3 (caspase-3a) polyclonal Ab, rabbit antiactivated caspase 9 (caspase-9a) polyclonal Ab, rabbit anti–procaspase-3 polyclonal Ab (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); rabbit anti–caspase-3 polyclonal Ab (CPP-32; Pharmingen); an anti-CD63 mAb (Beckmann Coulter, Villepinte, France); an anti–Cyt-c mAb (6H2.B4, Pharmingen); anti–poly adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribose polymerase (PARP) mAb (Oncogene, Boston, MA); antigelsolin mAb (Transduction Laboratories, Le Pont de Claix, France); and an anti–von Willebrand factor (VWF) mAb (gift from Dr D. Meyer, INSERM U143, Kremlin Bicêtre, France).

For indirect immunofluorescence, donkey tetramethyl rhodamine (TRITC)–labeled antimouse, TRITC-labeled antigoat, or FITC-labeled antirabbit F(ab′) 2 fragments (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) were used.

z-VAD-fluoromethylketone (fmk) was obtained from Biomolecular Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA) and staurosporin (STS) from Sigma Chemical (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). The calpain inhibitor I (Ac-Leu-Leu-norleucinal), the z-DEVD.fmk (caspase–3/7 inhibitor), and the z-LEDH.fmk (caspase-9 inhibitor) were obtained from Alexis (San Diego, CA).

In vitro generation of megakaryocytic cells

Blood CD34+ cells were isolated from leukapheresis samples performed on patients after mobilization, from umbilical cord blood, and from bone marrow of healthy patients undergoing hip surgery, as previously reported.29 Briefly, cells were separated over a Ficoll-metrizoate gradient (Biochrom KG, Berlin, Germany) and CD34+ cells were then isolated using the immunomagnetic beads technique (mini MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France), in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. The purity of CD34+ cells recovered was determined by flow cytometry and was greater than 80%. CD34+ cells were cultured in serum-free media supplemented with 10 ng/mL polyethylene glycol recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF), a truncated form of TPO (a gift from Kirin Brewery, Tokyo, Japan). CD34+CD41+ cells were subsequently sorted with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) Vantage cytometer (Becton Dickinson) at day 8 of culture and then grown in 96-well plates in a 100 μL volume in the presence of 10 ng/mL PEG-rHuMGDF in the presence or absence of different caspase inhibitors and 2 μM STS. Proplatelet-displaying MKs were defined as cells exhibiting one or more cytoplasmic processes with areas of constriction. The percentage of MKs with such processes was quantified by enumerating 500 cells per well with an inverted microscope at a magnification of × 200.

Cell staining protocols

Cells were cytospun onto slides at 550 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 4 minutes and processed as previously reported.30 Briefly, cells were subsequently fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at RT for 5 minutes, and blocked with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) prior to incubation with the anti–caspase-3a and anti–procaspase-3 or anti-VWF Abs. After 3 washes, cells were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies. DNA was then labeled with 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in Vectashield (Vector, Burlingame, CA) or Hoechst 33342 (Sigma Chemical) and slides were mounted. In some experiments, cells were stained by PhiPhiLux-G1D2, green fluorescence, a caspase-3 substrate (Alexis), in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. Cells were subsequently washed, fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, treated by 0.1% Triton X-100 for 3 minutes, and incubated with the anti-VWF Ab, which was revealed by a TRITC-conjugated donkey-antimouse Ab. For simultaneous assessment of DNA fragmentation and caspase 3 activation, a double staining was performed using the anti–caspase-3a Ab and the terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) technique. Briefly, after 1 hour's adherence on polylysine-coated slides at 37°C, MKs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT. Cells were rehydrated with Tris buffer saline and then permeabilized by 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes and washed. The anti–caspase-3 staining was performed as above, followed by the TUNEL technique according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Oncogene).

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100 treatment (Sigma Chemical). Cells were washed, incubated with the R-PE anti–Bcl-2 mAb, washed again, and analyzed on a FACSort (Becton Dickinson).

Conventional and confocal microscopy

Conventional examination of samples was performed with a fluorescence microscope equipped with the appropriate filter combinations (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Confocal microscopy was performed on a Leica TC-SP (Leica Microsystems, Rueil Malmaison, France) equipped with an Argon Krypton laser and an Argon laser mounted on an inverted Leica DM IFBE microscope with a UV 100 × 1.4NA oil objective. To avoid cross-talk between different fluorochromes, images were acquired in a sequential fashion.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested at indicated times, washed with PBS, and lysed in Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) buffer. Protein concentration was determined with Bio-Rad protein assay (Biorad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts were boiled for 5 minutes in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5% glycerol, 5% mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 0.05% bromophenol blue) and subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond; Biorad) and blocked overnight at 4°C in PBS, 0.1% Tween, containing 5% nonfat dried milk. Blots were incubated with an anti–caspase-3 polyclonal Ab (CPP-32; Pharmingen), an anti–caspase-9 polyclonal Ab (Cell Signaling Technology), an antigelsolin mAb (Transduction Laboratories), and an anti-PARP (Oncogene) mAb and detected with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Bioscience Europe, Orsay, France). Filters were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL kit; Amersham).

Retroviral plasmid constructs

The MFG-GFP plasmid was constructed by inserting a green fluorescent protein (GFP) insert (pIRES-EGFP; Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) into Nco1-BamH1 restriction sites of MFG backbone plasmid 27 under the control of the retroviral long terminal repeats (LTR) promoter. To construct the MFG-Bcl-2/internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)/GFP (MFG-BIG), 2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–amplified fragments containing, respectively, the 0.9 kilobase (kb) of the human Bcl-2 cDNA flanked byNco1-EcoR1 restriction sites and the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) IRES flanked byEcoR1-Nco1 restriction sites, were coinserted into the Nco1 site of the MFG-GFP plasmid. A Nco1 site generating a consensus Kozak sequence which replaced the original Bcl-2 ATG in order to strengthen the traduction.

Generation and culture of producer lines

The TELCeB6 packaging cell line (kindly provided by F. L. Cosset, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Villeurbanne, France) was cotransfected with the MFG and p respiratory syncytial virus glycoprotein G (pRSV) neoplasmids (10/1) using DOTAP (1,2-dioleoyl trimethylammonium propane), according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Gibco BRL, Invitrogen, Groningen, the Netherlands). After G418 selection (Gibco BRL; 1 mg/mL) and cloning, supernatants were collected and tested for their ability to transduce NIH3T3 cells. The best producer clone for each construct was identified by Southern blot. The titers obtained were 2.5 × 106 plaque-forming units (pfu)/mL for the MFG-BIG retrovirus and 5 × 106pfu/mL for MFG-GFP retrovirus.

MK infection

CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence of PEG-rHuMGDF. At day 6, 3 × 105 cells were cocultured for 2 days at 37°C in 6-well plates containing subconfluent monolayers of either MFG-BIG or MFG-GFP virus-producing cells. Coculture medium consisted of α–minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco BRL) in the presence of PEG-rHuMGDF. Nonadherent cells were sorted 48 hours later after incubation with the R-PE anti-CD41a mAb.

Results

Caspase inhibition blocks proplatelet formation

Studies using animal models have suggested that caspase inhibition induces thrombocytopenia. We therefore hypothesized that a platelet release defect might be due to an inhibition of proplatelet formation. Indeed, in the absence of formation of such extensions, a decrease in platelet release is observed. We therefore cultured human CD34+ cells in a liquid serum-free culture system in the presence of TPO until day 7. At day 8, a purified MK population (CD34+/CD41a+) was sorted by flow cytometry and cultured in 96-well tissue culture plates to quantify proplatelet-displaying MKs.29 Cells were then cultured in the presence of TPO, with or without caspaselike inhibitors (z-VAD.fmk, z-LEDH.fmk, z-DEVD.fmk) or an apoptosis inducer (STS). Control MKs had a round morphology until day 8, when some MKs began to change their form (Figure1A) and harbored long extensions, corresponding to proplatelet formation from day 9 to day 14 (Figure1B,C,E). Similar results were obtained for adult blood–derived MKs from day 10 to day 14 and for cord blood–derived MKs from day 12 to day 16, although the percentage of MKs exhibiting proplatelet formation was lower than that observed with peripheral blood and bone marrow MK cultures. The use of the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD.fmk, over a dose range of 50 to 100 μM added at day 8 in the culture medium, led to an almost complete inhibition of proplatelet formation (Figure 1D-F). In contrast, when MKs had started to display proplatelets, the addition of z-VAD.fmk had almost no effect on further proplatelet production. No differences were observed between control MKs and MKs cultured in the presence ofz-VAD.fmk in terms of viability, assessed by 7 amino–actinomycin D (7-AAD). The use of STS led to cell death and no proplatelet formation occurred. To further investigate the contribution of the 2 main caspases involved in the intrinsic pathway, we used the caspase-9 inhibitor z-LEDH.fmk and the caspase-3 inhibitor z-DEVD.fmk. Both these inhibitors reduced proplatelet formation, but to a slightly lesser extent than z-VAD.fmk (Figure 1E,F). In striking contrast, calpain inhibitor I had no significant effects on proplatelet formation (Figure 1F).

Inhibition of platelet formation by caspase inhibitors.

CD34+ cells purified from marrow were cultured in the presence of TPO. CD34+CD41+ cells were FACS-purified, as detailed in “Materials and methods.” at day 8 of culture. The sorted cells were further cultured in the presence of TPO with or without caspase inhibitors (Z-VAD.fmk, Z-LEDH.fmk, or Z-DEVD.fmk) or the apoptosis inducer STS. Representative micrographs of MKs at day 8 in the presence of TPO (A); at day 12 in the presence of TPO (B,C [C illustrates a proplatelet-forming MK at day 12 at a higher magnification]); and at day 12 in the presence of TPO plus 50 μM z-VAD.fmk (D). Original magnification, × 100. The kinetics of proplatelet formation in the presence or absence of different caspase inhibitors and STS is also shown (E). Results are means of 3 independent determinations; 3 experiments gave identical results. In panel F, the effects of calpeptin, Z-VAD, DEVD, and LEHD on proplatelet formation are compared at day 12 of culture in 3 experiments.

Inhibition of platelet formation by caspase inhibitors.

CD34+ cells purified from marrow were cultured in the presence of TPO. CD34+CD41+ cells were FACS-purified, as detailed in “Materials and methods.” at day 8 of culture. The sorted cells were further cultured in the presence of TPO with or without caspase inhibitors (Z-VAD.fmk, Z-LEDH.fmk, or Z-DEVD.fmk) or the apoptosis inducer STS. Representative micrographs of MKs at day 8 in the presence of TPO (A); at day 12 in the presence of TPO (B,C [C illustrates a proplatelet-forming MK at day 12 at a higher magnification]); and at day 12 in the presence of TPO plus 50 μM z-VAD.fmk (D). Original magnification, × 100. The kinetics of proplatelet formation in the presence or absence of different caspase inhibitors and STS is also shown (E). Results are means of 3 independent determinations; 3 experiments gave identical results. In panel F, the effects of calpeptin, Z-VAD, DEVD, and LEHD on proplatelet formation are compared at day 12 of culture in 3 experiments.

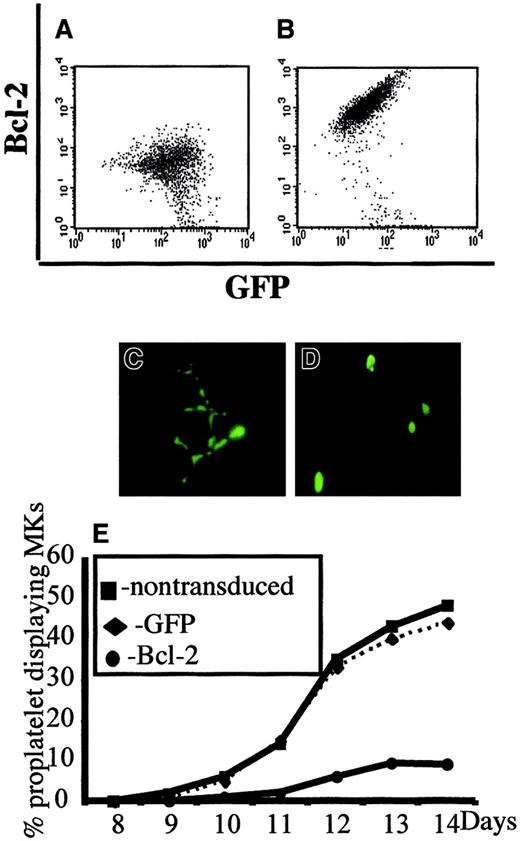

In a second set of experiments, we overexpressed Bcl-2 in MKs to investigate whether Bcl-2, by its ability to inhibit MMP and mitochondria-mediated caspase activation, could block platelet formation. CD34+ cells were cocultured with a TELCeB6 producer cell clone containing either the MFG-GFP (control) or MFG-BIG vector. The latter cell line produces a bicistronic retrovirus containing a bicistronic vector coding for Bcl-2 and GFP cDNAs separated by an IRES. After 2 days of coculture, cells were sorted by flow cytometry into CD41a+/GFP+ and CD41a+/GFP− populations and were cultured in 96-well tissue culture plates in the presence of TPO. The efficacy of Bcl-2 expression was assessed by flow cytometry and a correlation was confirmed between Bcl-2 and GFP expression (Figure2A,B). We then enumerated proplatelet-displaying MKs in different conditions (Figure 2C-E). No detrimental effect of GFP expression was observed in the samples cocultured with the MGF-GFP packaging cell line, because the frequency of proplatelet-displaying MKs was identical between the CD41+/GFP+ and CD41+/GFP− cell populations (Figure 2C,E). In contrast, overexpression of Bcl-2 led to a significant decrease in the percentage of proplatelet-displaying MKs as compared with CD41+/GFP− cells (Figure 2D,E). In addition, no proplatelet formation was observed in MKs expressing the highest level of Bcl-2 and GFP (Figure 2D). Together, these experiments strongly suggest that proplatelet formation is regulated by a mechanism involving mitochondria and caspase activation; however, induction of cell death does not lead to proplatelet formation.

Inhibition of platelet formation by Bcl-2 overexpression.

Bone marrow CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence of TPO. At day 6, cells were cocultured for 2 days with cells producing either the MFG-GFP or MFG-BIG virus. MKs transduced by the retroviral vectors were sorted on the expression of CD41 (R-PE) and GFP. GFP+ CD41+ and CFP−CD41+ cells were subsequently cultured with TPO and proplatelet formation was studied. Panels A and B: analysis by flow cytometry of the correlation between GFP and Bcl-2 expression in MFG-GFP–transduced cells (A) and MFG-BIG–transduced cells (B). In these cells a linear relationship between GFP and Bcl-2 is observed. Panels C and D: representative MKs obtained after MFG-GFP and MFG-BIG transduction. Proplatelet-forming MKs expressing GFP are found after transduction with the MFG-GFP virus (C), while MKs expressing GFP remain round after transduction with the MFG-BIG virus (D). Original magnification, × 150. Panel E: Kinetics of proplatelet formation in Bcl-2–overexpressing MKs. The graph shows a significant inhibition of proplatelet formation by Bcl-2–overexpressing MKs (one experiment made in triplicate). Experiments were repeated 3 times and yielded similar results each time.

Inhibition of platelet formation by Bcl-2 overexpression.

Bone marrow CD34+ cells were cultured in the presence of TPO. At day 6, cells were cocultured for 2 days with cells producing either the MFG-GFP or MFG-BIG virus. MKs transduced by the retroviral vectors were sorted on the expression of CD41 (R-PE) and GFP. GFP+ CD41+ and CFP−CD41+ cells were subsequently cultured with TPO and proplatelet formation was studied. Panels A and B: analysis by flow cytometry of the correlation between GFP and Bcl-2 expression in MFG-GFP–transduced cells (A) and MFG-BIG–transduced cells (B). In these cells a linear relationship between GFP and Bcl-2 is observed. Panels C and D: representative MKs obtained after MFG-GFP and MFG-BIG transduction. Proplatelet-forming MKs expressing GFP are found after transduction with the MFG-GFP virus (C), while MKs expressing GFP remain round after transduction with the MFG-BIG virus (D). Original magnification, × 150. Panel E: Kinetics of proplatelet formation in Bcl-2–overexpressing MKs. The graph shows a significant inhibition of proplatelet formation by Bcl-2–overexpressing MKs (one experiment made in triplicate). Experiments were repeated 3 times and yielded similar results each time.

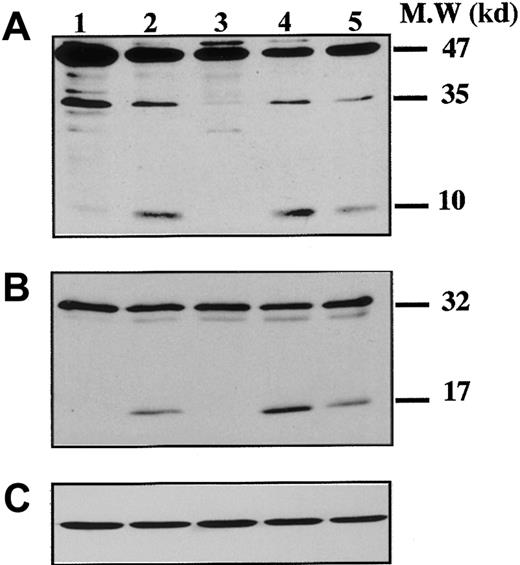

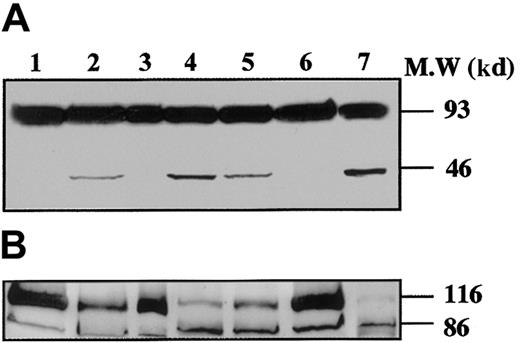

Caspase activation during MK maturation

To demonstrate that caspases were effectively activated during proplatelet formation, we performed Western blots with Abs directed against caspase-9 on samples from marrow CD34+–derived MKs at different days of culture (Figure 3). At day 8 of culture, the anti–caspase-9 Ab recognized a 47-kd band, corresponding to unprocessed procaspase-9, and a 35-kd band, corresponding to the cleaved form (Figure 3A). The small cleavage fragment (10 kd) was not detected, suggesting that only a minor fraction of procaspase 9 was cleaved. In contrast, at day 12 (lane 2), presence of the 10-kd form was markedly increased, as it was also after STS treatment. At day 12 the proteolytic maturation of procaspase-9 was totally inhibited by z-VAD.fmk. Procaspase-3 (32 kd) was found to be cleaved to yield the active form (17 kd) (Figure 3B), while in contrast, no processed caspase-3 was detected at earlier time points (day 6 or 8). As before, the proteolytic maturation of caspase-3 was totally inhibited by z-VAD.fmk. At day 6 of the culture the caspase-3 substrate, gelsolin, was essentially found in its native form (93 kd) (Figure 4A), while at days 11 and 13 it was partially cleaved into a 46-kd form when the MKs were shedding platelets. This process was reversed by z-VAD.fmk and was increased following STS treatment. Similar results were obtained for PARP, another executioner caspase substrate (Figure 4B). PARP was essentially found in its native form (116 kd) at day 6 of culture. It was partially cleaved into an 86-kd apoptotic-related cleavage fragment when platelet-shedding MKs were present. Together, these experiments demonstrate a functional activation of caspase during MK maturation, before the terminal phase of its life span.

Kinetics of caspase cleavage during MK differentiation.

Bone marrow CD34+ cells were cultured as in Figure 1. Western blot analyses were performed with anti–human caspase-9 (A) and anti–human caspase-3 (B) Abs. Equal loading was checked by stripping the membranes and reprobing with antiactin mAb (C). Positions of molecular mass markers are indicated at the right. Note that the 10-kd subunit of caspase-9 and the 17-kd active subunit of caspase-3 are not found in MKs lysed at day 8 (lane 1), detected when MKs are shedding platelets at day 12 of culture (lane 2). This cleavage is inhibited by z-VAD.fmk (lane 3), is increased by STS treatment (lane 4), and is also found later in culture, at day 13 (lane 5). Experiments were repeated twice and yielded similar results.

Kinetics of caspase cleavage during MK differentiation.

Bone marrow CD34+ cells were cultured as in Figure 1. Western blot analyses were performed with anti–human caspase-9 (A) and anti–human caspase-3 (B) Abs. Equal loading was checked by stripping the membranes and reprobing with antiactin mAb (C). Positions of molecular mass markers are indicated at the right. Note that the 10-kd subunit of caspase-9 and the 17-kd active subunit of caspase-3 are not found in MKs lysed at day 8 (lane 1), detected when MKs are shedding platelets at day 12 of culture (lane 2). This cleavage is inhibited by z-VAD.fmk (lane 3), is increased by STS treatment (lane 4), and is also found later in culture, at day 13 (lane 5). Experiments were repeated twice and yielded similar results.

Time-course of gelsolin and PARP processing during MK differentiation.

CD34+ cells were cultured during 6 days (lane 1), 11 days (lanes 2-4), and 13 days (lanes 5-7), in the presence of TPO only (lanes 1, 2, 5), TPO and Z-VAD.fmk from day 8 to day 11 (lanes 3 and 6) or TPO and STS during the last 12 hours (lanes 4 and 7). Cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting with antigelsolin mAb (A) or anti-PARP antibody (B). Full-length gelsolin (A) and PARP (B) (migrating at 93 kd and 116 kd, respectively) and their cleavage products (46 kd and 86 kd, respectively) are indicated. The cleaved subunit was not detected when cells were cultured for 6 days in the presence of TPO (lane 1) and was present in mature MKs (lanes 2 and 5). This process is completely reverted by the inhibitor z-VAD.fmk (lanes 3 and 6), and the cleaved form is increased after STS treatment (lanes 4 and 7).

Time-course of gelsolin and PARP processing during MK differentiation.

CD34+ cells were cultured during 6 days (lane 1), 11 days (lanes 2-4), and 13 days (lanes 5-7), in the presence of TPO only (lanes 1, 2, 5), TPO and Z-VAD.fmk from day 8 to day 11 (lanes 3 and 6) or TPO and STS during the last 12 hours (lanes 4 and 7). Cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting with antigelsolin mAb (A) or anti-PARP antibody (B). Full-length gelsolin (A) and PARP (B) (migrating at 93 kd and 116 kd, respectively) and their cleavage products (46 kd and 86 kd, respectively) are indicated. The cleaved subunit was not detected when cells were cultured for 6 days in the presence of TPO (lane 1) and was present in mature MKs (lanes 2 and 5). This process is completely reverted by the inhibitor z-VAD.fmk (lanes 3 and 6), and the cleaved form is increased after STS treatment (lanes 4 and 7).

Early caspase activation occurs before proplatelet formation and is sequestered in the cytoplasm of maturing MKs

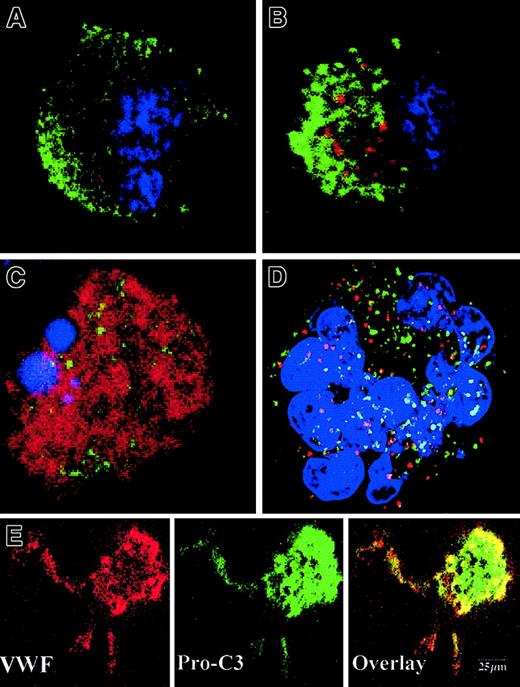

To precisely determine the relationship between caspase activation and proplatelet formation, we investigated the precise kinetics of caspase activation at the cellular level. A confocal analysis revealed the presence of activated caspase-3 (caspase-3a) in a fraction of the day-8 round MKs, which continued to be detected until day 13 (Figure5A,B). This labeling was granular with a variable number of patches, from 4 or 5 to 100. This labeling did not colocalize with the anti-VWF (Figure 5B) or the anti-CD63 staining (Figure 5D), suggesting that caspase-3a was not localized in α-granules or in lysosomes. In contrast, a diffuse caspase-3a staining was detected in senescent MKs (Figure 5C) or in MKs induced to undergo apoptosis by STS. In MKs associated with a diffuse caspase-3 activation, VWF staining was weak in contrast to the MKs with a localized activation of caspase-3 (compare Figures 5B and 5C). We next questioned whether the procaspase-3 was present in the whole cell or compartmentalized in the cytoplasm, using an anti–procaspase-3 Ab. As expected, the proenzyme form of the procaspase-3 was present in the whole cell, including proplatelets, with a diffuse staining (Figure5E). We then quantified the number of MKs with a granular labeling with an anti–caspase-3a Ab. Their number was low at day 7 (6%, n = 2) and peaked between day 10 and day 12 (30%, n = 10), prior to maximum platelet shedding. Caspase activation under a granular form was increased in MKs shedding platelets (about 50%) in comparison with the other round MKs. This suggests that localized activation of the caspase-3 precedes proplatelet formation and persists during this process. Similar experiments were performed with an antiactivated caspase-9 antibody. Although labeling was much weaker, some MKs exhibited the characteristic patchy appearance (data not shown).

Activated caspases are localized in the cytoplasm of maturing MKs.

Mobilized blood CD34+ cells were cultured as in Figure 1. Panels A-D: labeling with the anti–caspase-3a Ab (red). In panels A-C, a double labeling was performed between the anti–caspase-3a Ab (red) and the anti-VWF Ab (green). DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Cells were examined by confocal microscopy and an overlay representation is shown. Results illustrate a typical section. Round maturing MKs may have either no labeling with the anti–caspase-3 Ab (A) or a granular pattern of staining (B). This granular labeling does not colocalize with the anti-VWF staining. In panel C, an apoptotic MK, as shown by the DAPI labeling, has a diffuse staining by the anti–caspase-3a Ab. In panel D, a double labeling between the anti–caspase-3a Ab (red) and anti-CD63 Ab (green) is illustrated. No colocalization between these 2 labelings was found. Panel E: labeling with an anti–procaspase-3 Ab (green). Two-color immunofluorescence localization of procaspase-3 (green) and VWF (red). Note that procaspase-3 is present in the cytoplasm of proplatelet-forming MKs, including the proplatelets with a diffuse staining pattern. Original magnification, × 1000.

Activated caspases are localized in the cytoplasm of maturing MKs.

Mobilized blood CD34+ cells were cultured as in Figure 1. Panels A-D: labeling with the anti–caspase-3a Ab (red). In panels A-C, a double labeling was performed between the anti–caspase-3a Ab (red) and the anti-VWF Ab (green). DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Cells were examined by confocal microscopy and an overlay representation is shown. Results illustrate a typical section. Round maturing MKs may have either no labeling with the anti–caspase-3 Ab (A) or a granular pattern of staining (B). This granular labeling does not colocalize with the anti-VWF staining. In panel C, an apoptotic MK, as shown by the DAPI labeling, has a diffuse staining by the anti–caspase-3a Ab. In panel D, a double labeling between the anti–caspase-3a Ab (red) and anti-CD63 Ab (green) is illustrated. No colocalization between these 2 labelings was found. Panel E: labeling with an anti–procaspase-3 Ab (green). Two-color immunofluorescence localization of procaspase-3 (green) and VWF (red). Note that procaspase-3 is present in the cytoplasm of proplatelet-forming MKs, including the proplatelets with a diffuse staining pattern. Original magnification, × 1000.

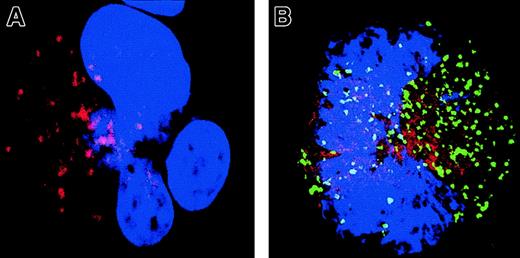

Early caspase activation is functional but does not lead to cell death

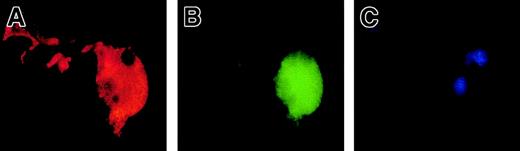

To demonstrate a functional activation of caspase-3, we used a fluorescent substrate of caspase-3, PhiPhiLux. Cultured cells were stained with an anti-VWF Ab and PhiPhiLux. A fraction of mature MKs (about 10%) at day 10, including platelet-shedding MKs (Figure6A-C), were labeled by the PhiPhiLux. None of the mature MKs exhibited clear signs of apoptosis, based on the chromatin condensation. Moreover, we performed double staining with an Ab specific to activated caspase-3, and DNA strand breaks revealed by the TUNEL reaction. Senescent MKs or STS-induced apoptotic MKs with diffuse caspase-3a exhibited DNA fragmentation (Figure7A-C), while in contrast, the MKs with patchy and discrete activated caspase-3 retained their DNA integrity (Figure 7D-F).

A cleavage of a caspase-3 substrate (PhiPhiLux) is observed in proplatelet-displaying MKs.

Mobilized blood CD34+ cells were cultured as in Figure 1. A proplatelet-displaying MK at day 12 shows a diffuse staining pattern with PhiPhiLux (A, green fluorescence), predominantly in the perinuclear area. Labeling in the proplatelet is weak. The VWF (red fluorescence) is present in the whole cytoplasm, including proplatelets (B). (C): Nucleus stained with DAPI. Original magnification, × 630.

A cleavage of a caspase-3 substrate (PhiPhiLux) is observed in proplatelet-displaying MKs.

Mobilized blood CD34+ cells were cultured as in Figure 1. A proplatelet-displaying MK at day 12 shows a diffuse staining pattern with PhiPhiLux (A, green fluorescence), predominantly in the perinuclear area. Labeling in the proplatelet is weak. The VWF (red fluorescence) is present in the whole cytoplasm, including proplatelets (B). (C): Nucleus stained with DAPI. Original magnification, × 630.

No DNA fragmentation is detected in MKs with a localized activation of caspase-3.

A double staining between the anti–caspase-3a Ab (red) and the TUNEL technique (green) was performed. The nucleus was labeled with DAPI. Panels A-C: an apoptotic MK that exhibited a condensed chromatin (B) is stained in green by the TUNEL technique (C). This MK has a diffuse and strong labeling by the anti–caspase-3a Ab (A). In panels D- F, a maturing MK is illustrated. Chromatin does not show signs of condensation (E). No DNA fragmentation is detectable by the TUNEL technique (F). However, a granular pattern of labeling by the anti–caspase-3a Ab is observed (D). Original magnification, × 630.

No DNA fragmentation is detected in MKs with a localized activation of caspase-3.

A double staining between the anti–caspase-3a Ab (red) and the TUNEL technique (green) was performed. The nucleus was labeled with DAPI. Panels A-C: an apoptotic MK that exhibited a condensed chromatin (B) is stained in green by the TUNEL technique (C). This MK has a diffuse and strong labeling by the anti–caspase-3a Ab (A). In panels D- F, a maturing MK is illustrated. Chromatin does not show signs of condensation (E). No DNA fragmentation is detectable by the TUNEL technique (F). However, a granular pattern of labeling by the anti–caspase-3a Ab is observed (D). Original magnification, × 630.

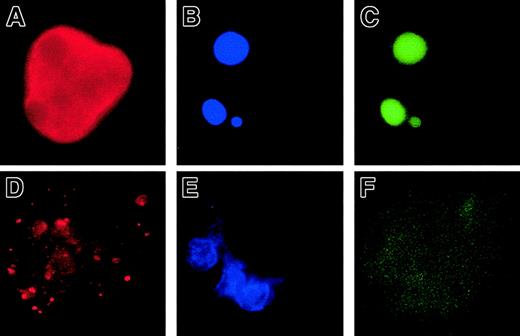

Signs of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (MMP) are present in MKs with a localized activation of caspase

To confirm that caspase activation involves a critical Bcl-2–controlled step, we explored the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway of caspase activation. Cyt-c release was measured using double immunostaining with antibodies specific for Cyt-c (TRITC) and caspase-3a (Figure 8). In MKs having no detectable caspase-3 activation, staining with the anti–Cyt-c was strong and punctuate (Figure 8A). Cyt-c and Bcl-2 have the same pattern of labeling, suggesting that Cyt-c is mainly localized in mitochondria (data not shown). In contrast, MKs that exhibited a patchy activation of caspase-3 had a much weaker and diffuse staining, suggesting that Cyt-c is released from mitochondria and gains access into the cytosol (Figure 8B). A similar observation was made in MKs with a diffuse caspase-3 activation and nuclear signs of apoptosis, although Cyt-c expression was at the threshold of detection.

Localized caspase-3 activation in maturing MKs is associated with a cytosol release of Cyt-c.

A double staining between the anti–caspase-3 Ab (green) and Cyt-c Ab (red) was performed. Cells were counterstained with DAPI and examined by confocal microscopy. An overlay illustration of the labeling is shown. A MK without signs of localized caspase-3 activation (A) has a typical granular labeling with the anti–Cyt-c Ab (red). This pattern of labeling corresponds to labeling in mitochondria when double labeling is performed with an anti–Bcl-2 Ab (data not shown). In contrast, in an MK having granular labeling with the anti–caspase-3 Ab (green; B), labeling with the anti–Cyt-c (red) is weaker and more diffuse, demonstrating signs of MMP in this cell. Original magnification, × 1000.

Localized caspase-3 activation in maturing MKs is associated with a cytosol release of Cyt-c.

A double staining between the anti–caspase-3 Ab (green) and Cyt-c Ab (red) was performed. Cells were counterstained with DAPI and examined by confocal microscopy. An overlay illustration of the labeling is shown. A MK without signs of localized caspase-3 activation (A) has a typical granular labeling with the anti–Cyt-c Ab (red). This pattern of labeling corresponds to labeling in mitochondria when double labeling is performed with an anti–Bcl-2 Ab (data not shown). In contrast, in an MK having granular labeling with the anti–caspase-3 Ab (green; B), labeling with the anti–Cyt-c (red) is weaker and more diffuse, demonstrating signs of MMP in this cell. Original magnification, × 1000.

Taken together, these experiments clearly demonstrate an activation of caspase preceding proplatelet formation. However, active forms of caspases were specifically localized in granules; this compartmentalization was lost in apoptotic MKs. Sequestration of caspase activation may lead to regional cell death (sparing proplatelets), while extended activation would lead to death of the entire cell.

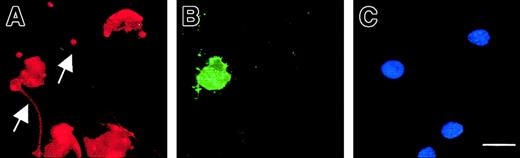

Signs of apoptosis are also compartmentalized on the plasma membrane surface of MKs shedding platelets

Exposure of phosphatidylserine residues on the plasma membrane surface (determined with annexin V) was not detectable in maturing MKs, except in MKs exhibiting features of apoptosis (Figure9). In proplatelet-displaying MKs, surface phosphatidylserine was detected on the cell membrane except along the proplatelets. Proplatelets disrupted from MKs were also negative for surface phosphatidylserine.

Compartmentalized membrane exposure of phosphatidylserine in proplatelet-displaying MKs.

Live 13-day-old budding MKs were stained with FITC–annexin V (B) and counterstained with a R-PE anti-CD41 mAb (A) as well as Hoechst 3324 (C). Note that in the entire MK-forming platelet, the proplatelets (arrow) does not stain with annexin V, although the central part of the MK is positive for annexin V, indicating localized membrane phosphatidylserine exposure. The arrowhead points to a proplatelet (annexin negative) originating from another MK that is not shown in this field. In the other MKs, no staining with FITC–annexin V is observed. Scale bar equals 20 μm.

Compartmentalized membrane exposure of phosphatidylserine in proplatelet-displaying MKs.

Live 13-day-old budding MKs were stained with FITC–annexin V (B) and counterstained with a R-PE anti-CD41 mAb (A) as well as Hoechst 3324 (C). Note that in the entire MK-forming platelet, the proplatelets (arrow) does not stain with annexin V, although the central part of the MK is positive for annexin V, indicating localized membrane phosphatidylserine exposure. The arrowhead points to a proplatelet (annexin negative) originating from another MK that is not shown in this field. In the other MKs, no staining with FITC–annexin V is observed. Scale bar equals 20 μm.

Discussion

Platelet release depends on the formation of MK cytoplasmic extensions called proplatelets. In the absence of such extensions, only a few, if any, platelets are released.16 The appearance of proplatelets delineates 2 main regions in mature MKs, with distinct fates: proplatelets, which will engender functional platelets in the blood flow,5,10,11 and the central area of the MK surrounding the nucleus, which will give rise to senescent MKs. This denuded MK remains in the bone marrow, undergoes an apoptotic process, and is phagocytosed by macrophages.18,19 Previous studies have suggested that at the terminal phase of the MK life span, platelet production and MK apoptosis are closely related events.19Moreover, nitric oxide–induced apoptosis facilitates platelet production during the final stages of megakaryocytopoiesis.31

Here, we provide evidence that activation of the apoptotic cell machinery is directly involved in differentiation and platelet shedding: its activation is necessary not only for cell death but also for the formation of proplatelets. The first line of evidence that platelet formation has some similarities to apoptosis is that proplatelet formation was associated with a cleavage of caspase-9 and caspase-3 in MKs derived from cord blood, mobilized blood, or bone marrow CD34+ cells. Procaspase-3 cleavage gave rise to the enzymatically active caspase-3 fragment because gelsolin and PARP were cleaved when MKs were shedding platelets. The second line of evidence is that the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD.fmk could inhibit proplatelet formation. This process was temporally controlled. Indeed, once proplatelet formation had been initiated,z-VAD.fmk had few, if any, effects. However,z-VAD.fmk is also capable of inhibiting calpain, which has recently been reported to promote apoptosislike events during platelet activation.32-34 However, proplatelet formation is not a calpain-dependent process, because a calpain inhibitor had no inhibitory effect. Furthermore, overexpression of Bcl-2 in CD41+ cells largely blocked proplatelet formation. This result also supports the contention that the thrombocytopenia observed in Bcl-2 transgenic mice is related to an inhibition of platelet production.20

A surprising finding was related to the granular distribution of caspase-3a in the cytoplasm of mature MKs. Staining with Abs against caspase-3a revealed a discrete punctuate distribution, which did not colocalize with VWF, a marker of α-granules, or CD63, a marker of lysosomes. Procaspase-3 was present in the cytosol of mature MKs, including in proplatelets. This is in agreement with recent results showing that all components of the apoptosome, including procaspase-9, procaspase-3, Apaf-1, and Cyt-c, are present in platelets.32,35 In senescent MKs or after STS-induced apoptosis, activated forms of caspases were present in the cytosol of MKs, suggesting that a diffuse caspase activation leads to apoptosis without proplatelet formation, whereas a restricted caspase activation may induce differentiation. This result also suggests that during late differentiation a subcellular caspase-3 activation would lead to proplatelet formation, whereas after proplatelet formation caspase activation switches from a localized to a diffuse form, which induces apoptosis in senescent MKs. The organelles in which activated caspase-3 is present remain to be determined, but it has been shown that caspase-3a may be sequestered into cytoplasmic inclusions in epithelial cells undergoing apoptosis.36 This sequestration may prevent cell damage and thus maintain the cell integrity. It has been suggested that this sequestration is associated with disassembly of the cytoskeleton, which may be important for proplatelet formation. The mechanism involved in this subcellular activation or sequestration of caspases is presently unknown. An interesting finding was that the activation of caspase-3 was associated with signs of MMP (release of Cyt-c through the outer membrane), suggesting that the mitochondrial pathway regulates this process.

The mechanism of proplatelet formation may mimic the blebbing that is observed at the onset of apoptosis.37,38 However, in contrast to blebbing, which is coupled to whole-cell death, platelet shedding is associated with regional cell death. Proplatelet formation is related to profound changes in the cytoskeleton, including activation of microtubules,5,10,13,39 polymerization of actin, and phosphorylation of myosin.11,14,40,41 Several cytoskeleton molecules or actin regulators, such as gelsolin, regulators of Rho family guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases), or their effectors, have been described as substrates of caspases during apoptosis.42-48 In particular, it has been shown that Rho-kinase cleavage by caspase-3 is responsible for apoptotic membrane blebbing by inhibiting myosin phosphatase.49-51Thus, it seems likely that caspase activation during proplatelet formation may lead to alteration in the actin cytoskeleton and myosin function, triggering a complex cytoplasm reorganization which, in contrast to blebbing, also involves cytoplasmic organelles. At present, we cannot exclude the possibility that some nonexecutioner caspases are also involved in this process. For example, it has been recently shown that caspase-14 is associated with keratinocyte terminal differentiation.25

From these experiments it can be hypothesized that a compartmentalization of caspase activation occurs during MK differentiation, which leads to proplatelet formation. This compartmentalization may affect not only the cytoplasm but also the plasma membrane. Indeed, phosphatidylserine exposure was detectable only on the cytoplasmic membrane around the nucleus, not on proplatelets (data not shown). Expression of phosphatidylserine on the external plasma membrane triggers phagocytosis,52 in agreement with the fate of the senescent MKs.18 After proplatelet formation and platelet shedding, a complete activation of the apoptotic machinery subsequently leads to apoptosis in senescent MKs. Overall, this is reminiscent of the function of caspases during terminal erythroid differentiation26 and in the enucleation of other cell types.22,23 However, there is also increasing evidence that caspase-3 may play an important role in terminal differentiation of cells that remain nucleated53(also Sordet et al, manuscript submitted for publication).

In conclusion, limited caspase activation is directly implicated in proplatelet formation. Characterization of the molecules that regulate this process will provide new insights into the mechanisms linking differentiation and apoptosis and may allow us to better understand the mechanisms of congenital or acquired thrombocytopenia.

We thank Héléne Gilgenkrantz (U129, Institut Cochin de Génétique Moléculaire, Paris, France) for providing the MFG-BIG and MFG-GFP virus-producing cells; Valérie Schiavon (U362, Villejuif, France) for cell sorting experiments; Didier Métivier (CNRS, Unité Mixte de Recherche 1599, Villejuif) for confocal analysis; Catherine Boccacio (Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif) for providing cytapheresis samples; and Jean Luc Pallacio and Didier Letailleur (Beauvais, France) for providing bone marrow samples. We are grateful to Pierre Golstein (Centre d'Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy, Marseille, France), for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript and to Dr Jonathan Dando for greatly improving the English.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 7, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0686.

Supported by grants from INSERM, the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (N.D.), la Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (W.V. and G.K.), and the European Commission (G.K.).

E.D. and Y.Z. contributed equally to this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Najet Debili, INSERM U362, Institut Gustave Roussy, Institut Fédératif de Recherche 54, F-94805, Villejuif, France; e-mail: denali@igr.fr.

![Fig. 1. Inhibition of platelet formation by caspase inhibitors. / CD34+ cells purified from marrow were cultured in the presence of TPO. CD34+CD41+ cells were FACS-purified, as detailed in “Materials and methods.” at day 8 of culture. The sorted cells were further cultured in the presence of TPO with or without caspase inhibitors (Z-VAD.fmk, Z-LEDH.fmk, or Z-DEVD.fmk) or the apoptosis inducer STS. Representative micrographs of MKs at day 8 in the presence of TPO (A); at day 12 in the presence of TPO (B,C [C illustrates a proplatelet-forming MK at day 12 at a higher magnification]); and at day 12 in the presence of TPO plus 50 μM z-VAD.fmk (D). Original magnification, × 100. The kinetics of proplatelet formation in the presence or absence of different caspase inhibitors and STS is also shown (E). Results are means of 3 independent determinations; 3 experiments gave identical results. In panel F, the effects of calpeptin, Z-VAD, DEVD, and LEHD on proplatelet formation are compared at day 12 of culture in 3 experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/4/10.1182_blood-2002-03-0686/6/m_h81622960001.jpeg?Expires=1767714953&Signature=1WyuRZIRLe-f1veiGQIPI4VbCkhXazeTUKwxwP90baabNPT0rgEAZ6A-T4r08--11XM~c7zj8exJOaoKS8V2hw4D~viz9DaYzWL6yvfhOtmWhuzkOxfPHzrKqv1u9HTeFhGMBKJFEDcWkczC3Q5QbmM6lvKPqVNdstE6p5x4GlPKJWcjT4vpBceDayyuGjCDaxrOGIxiXB7exzKUpNPvIeMH4gdeDlEfR0fwPdfx8O6gAYQAvamMAPWz-5hk3YWGD2uzkGRi6vdVxazqQ3jjCJIUlvdVh48P3vC-HHfPmftvFyqA1wlK~QPurMxybj4hCiCn6h7-V4c6HIRUutHtyA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal