Platelet activation by thrombin or thrombin receptor-activating peptide (TRAP) results in extensive actin reorganization that leads to filopodia emission and lamellae spreading concomitantly with activation of the Rho family small G proteins, Cdc42 and Rac1. Evidence has been provided that direct binding of Cdc42-guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and Rac1-GTP to the N-terminal regulatory domain of the p21-activated kinase (PAK) stimulates PAK activation and actin reorganization. In the present study, we have investigated the relationship between shape change and PAK activation. We show that thrombin, TRAP, or monoclonal antibody (MoAb) anti-FcγRIIA IV.3 induces an activation of Cdc42 and Rac1. The GpVI ligand, convulxin (CVX), that forces platelets to lamellae spreading efficiently activates Rac1. Thrombin, TRAP, MoAb IV.3, and CVX stimulate autophosphorylation and kinase activity of PAK. Inhibition of Cdc42 and Rac1 with clostridial toxin B inhibits PAK activation and lamellae spreading. The cortical-actin binding protein, p80/85 cortactin, is constitutively associated with PAK in resting platelets and dissociates from PAK after thrombin stimulation. Inhibition of PAK autophosphorylation by toxin B prevents the dissociation of cortactin. These results suggest that Cdc42/Rac1-dependent activation of PAK may trigger early platelet shape change, at least in part through the regulation of cortactin binding to PAK.

Introduction

The actin cytoskeleton plays an important role in defining cell shape and morphology. Actin-rich filopodia and lamellipodia protrusions are thought to depend on the activation of small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) of the Rho subfamily, Cdc42 and Rac1, respectively.1,2 In platelets, stimulation by thrombin induces filopodia extension and lamellae spreading supported by massive actin polymerization. Subsequently to early shape change, platelets reorganize adhesion points mainly focused on integrin αIIbβ3 with emergence of stress fibers submitted to a regulation by Rho. In an attractive model of permeabilized platelets, it has been demonstrated that the introduction of a dominant-negative mutant N17Rac1 prevents exposure of actin filament barbed ends caused by thrombin, whereas a constitutively active mutant V12Rac1 promotes exposure of actin ends that precedes nucleation of new actin filaments.3 One work demonstrates that Cdc42 and Rac accumulate in activated GTP-bound forms in response to thrombin and that Cdc42 associates with actin cytoskeleton, whereas Rac relocalizes to the plasma membrane.4 However, except that Cdc42 and Rac1 must be activated before actin assembly, the steps between their activation and platelet actin remodeling are less known.

The p21-activated kinases (PAKs) are serine/threonine kinases that have been proposed as downstream effectors of those GTPases.5,6 At least 4 isoforms have been reported in mammals. PAKs exhibit a N-terminal regulatory domain with a GTPase-binding cassette, a proline-rich domain that binds SH3-containing proteins and a C-terminal kinase domain. The regulatory mechanisms of PAK activation have been extensively studied and result both from binding of Cdc42-GTP and Rac-GTP and autophosphorylation of serine/threonine residues in the regulatory domain that leads to opening of the molecule, transphosphorylation of threonine 423 in PAK1 or threonine 402 in PAK2, and substrate access to the kinase domain.7-9 Evidence has been provided that integrin interaction with extracellular matrix promotes the activation of Rac1/Cdc42 and PAK in the NIH 3T3 cell line,10 and it has been hypothesized that PAK also plays an important role in regulating actin stress fiber disassembly and, thus, the turnover of focal complexes. These effects are in part mediated through PAK phosphorylation and inhibition of the myosin light chain kinase11 and also through an upstream regulation of the focal adhesion adapter protein paxillin.12 In platelets aggregated in response to thrombin, PAK2 is rapidly activated.13 This finding suggests that PAK activation may play a primary role in extensive cytoskeleton reorganization in platelets.

The aim of the present work was to investigate the relationship between PAK activation and early platelet shape change prior to aggregation. Filopodia formation and lamellae spreading have been obtained from platelets stimulated through G-coupled protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1) by thrombin or thrombin receptor-activating peptide (TRAP) and through the low-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin G (IgG)–bearing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) FcγRIIA.14 In contrast, the ITAM (Gp)VI ligand, convulxin (CVX)15-17 only induces extensive lamellae spreading. Our results show that Cdc42/Rac1-dependent activation of PAK is necessary for lamellae spreading. Furthermore, the cortical actin-binding protein, cortactin that contributes to actin polymerization, is under the control of PAK activation.

Materials and methods

Agonists and antibodies

Human α-thrombin was purchased from Diagnostica Stago (Franconville, France) and TRAP (SFLLRNPNQKYEPF) was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Collagen suspension was from Biodata Corporation (Hatboro, PA). Monoclonal IV.3 antibody to FcγRIIA was from Medarex (Annandale, NJ), and convulxin was purified from the crude venom ofCrotallus durissus terrificus (Latoxan, Valence, France) as previously described.17 Platelet activation inhibitor prostaglandin E1 (PGE1), the calpain inhibitor, calpeptin, and the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–phalloidin toxin from Amanita phalloides were purchased by Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Antibodies for immunoblot or immunoprecipitation were the following: the rabbit polyclonal antihuman PAK2 directed to N-terminal amino acids 2 to 22, which partially cross-reacts with human PAK1, the rabbit polyclonal antirat PAK1/2 directed against C-terminal amino acids 525 to 544, which reacts with human PAK1 and PAK2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); the rabbit polyclonal antiphosphoPAK1/2 (Threonine 423/Threonine 402; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); the monoclonal anti-Rac1 (clone 23A8) antibody; and the monoclonal anti-p80/85 cortactin (clone 4F11) from Upstate Biotechnologies (Lake Placid, NY). The rabbit polyclonal anti-Cdc42 antibody was a gift from Dr Ph. Chavrier (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The monoclonal anti-G actin antibody and the sheep antimouse IgG F(ab′)2 were from Sigma-Aldrich. Rabbit anti–glutathione-S-transferase (GST) was provided by Dr P. Mayeux (Département d'Hématologie, Institut Cochin, Paris, France). Lethal toxin (LT) purified to homogeneity fromClostridium sordellii (strain IP82)18,19 and toxin B from Clostridium difficile prepared according to von Eichel-Streiber et al20 were obtained from Dr M. Popoff (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France).

Platelet isolation and stimulation

Platelets were isolated from venous blood collected from healthy volunteer donors. Blood was collected on 42 mM trisodium citrate, 42 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) as anticoagulant (1 volume anticoagulant/6 volumes blood). Prostaglandin E1 (1 μM) was added before isolation. Platelet-rich plasma was collected by centrifugation at 150g for 15 minutes at 20°C and diluted in wash buffer (10 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], pH 6.6, 136 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 25 mM glucose, 4.2 mM EDTA, 4.2 mM trisodium citrate, and 1 μM PGE1). Platelet suspension was centrifuged at 750g for 15 minutes at 20°C, and the pellet was resuspended in wash buffer without PGE1 for an additional centrifugation in the same conditions. Finally, platelets were recovered in suspension buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 136 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 25 mM glucose) at the concentration of 4 to 5 × 108 platelets/mL before stimulation with 0.5 UI/mL thrombin, 10 μM TRAP, 250 pmol/L convulxin, or 2 μg/mL IV.3 monoclonal antibody followed by 30 μg/mL sheep antimouse IgG F(ab′)2 at 37°C, without stirring. In some experiments, platelets were preincubated for 2 hours at 37°C with 1 μg/mL LT or toxin B before stimulation.

Flow cytometry

For quantification of actin polymerization, 50 μL of resting or stimulated platelets were fixed with 1.8% paraformaldehyde (PFA), washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4, and then incubated with 10 μM FITC-phalloidin for 30 minutes at room temperature in 0.02% Triton X-100 buffer. After 2 washes, samples were resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS pH 7.4 and analyzed by using an Epics Profile flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). Fluorescence signals were set in logarithmic gain. Fluorescence emission was monitored by using a 550-nm (FL1) band pass filter. Results were expressed as relative fluorescence emission intensity (RFI) of stimulated to resting platelets.

Confocal microscopy

After stimulation, with or without pretreatment with 1μg/mL LT or toxin B, platelets were fixed with 1.8% PFA for 5 minutes at room temperature, washed twice in PBS pH 7.40, and settled on glass slides. Platelets were labeled with 10 μM FITC-phalloidin for 30 minutes in 0.02% Triton X-100 containing PBS, washed twice in PBS, and mounted in Mowiol. Immunolocalization of Rac1, PAK, and cortactin was performed on PFA-fixed platelets settled on glass slides. Platelets were permeabilized in 0.03% saponin-containing PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 minutes at room temperature and then incubated with specific primary antibodies (1-10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 4°C. After 2 washes in PBS (pH 7.4), Rac1 and cortactin labeling was revealed by incubation with a goat antimouse-FITC secondary antibody, and PAK labeling was detected by incubation with a goat antirabbit-rhodamine secondary antibody (DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Purified irrelevant mouse or rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as negative controls. Fluorescent images (magnification × 100) were taken with a confocal krypton/argon laser scanning microscope (MRC-100, Bio-Rad, Hemel, Hempstead, UK) attached to a diaphot 300 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Production of GST-fused recombinant proteins and purification of recombinant human cortactin

The GTPase-binding domain (PBD) of human PAK1 (amino acids 67-150), PAK1 wild type (full length) in fusion with GST cloned into the bacterial expression vector pGEX-4T3 and PAK1 T423E (active mutant) in pCMV6m was a gift from Dr G. Bokoch (Scripps Institute, La Jolla, CA). PAK1 T423E cDNA was inserted into pGEX-4T3. GST-cortactin cloned into PXZ-122 was a gift from Dr X. Zhan (American Red Cross, Rockville, MD). GST-fused proteins were coupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads and stored at −80°C as a 50% suspension in 25 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)–HCl, pH 7.4, 0.2 mM DTT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), 1 mM MgCl2, and 5% glycerol. Recombinant human (rHu) cortactin was purified on a glutathione-Sepharose column and cleaved from GST by thrombin.

Affinity precipitation using GST-fused proteins

Precipitation of activated Rac1 or Cdc42 was performed according to Benard et al.21 Platelets were lysed in 25 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and protease inhibitors. Cytoskeletal and NP-40–soluble fractions were separated by centrifugation at 10 000g for 20 minutes. PBD-GST was used to trap Rac1-GTP or Cdc42-GTP in 100 μL NP-40–soluble fraction. Incubation was performed after addition of 200 μL binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT, 30 mM MgCl2, 40 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) for 1 hour at 4°C. The bead pellet was then washed 3 times in binding buffer, twice with the same buffer without Nonidet P-40, and finally resuspended in 20 μL Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were separated by 12% sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted by using either monoclonal anti-Rac1 antibody or polyclonal anti-Cdc42 antibody. In some experiments, cytoskeletal and NP-40–soluble fractions were analyzed for the expression of Cdc42 by direct immunoblotting. As controls, lysates were incubated with 100 μM either nonhydrolysable GTPγS or guanosine diphosphate (GDP) before precipitation on PBD-GST beads, and both bead pellets and supernatants were analyzed. Immunoblots were revealed with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom).

GST-PAK1WT and GST-PAK1T423E or GST-cortactin were used to pull down cortactin or PAK, respectively, from platelets lysed in solubilization buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 5 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 mM benzamidine, 10 μg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot

After stimulation, platelets were lysed in 3× solubilization buffer for 20 minutes on ice. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 4°C for 10 minutes at 10 000g and precleared by incubation for 1 hour at 4°C with 20 μL protein G–Sepharose 4B packed beads. In some experiments, lysates were sonicated and incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with DNase I (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). Immunoprecipitations were performed for 2 hours in ice with 5 μg/mL polyclonal anti-PAK2 or monoclonal anticortactin antibodies. Immune complexes were collected on 25 μL protein G–Sepharose 4B packed beads during 1 hour at 4°C under agitation. Beads were washed 3 times in 1× solubilization buffer and twice in the same buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Proteins were solubilized in Laemmli buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for specific immunoblotting.

PAK in vitro kinase assay

PAK was immunoprecipitated as described above. Dried beads were recovered in 1 × kinase buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MnCl2, 0.4 mM DTT). Purified myelin basic protein (MBP; 1 μg) or 5 μg purified rHu cortactin was added, and the reaction was started by the addition of a mixture of 20 μM MgCl2-adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and 0.185 MBq (5 μCi) γ[32P]-ATP (specific activity, 111 TBq/mmol) in 40 μL 1× kinase buffer for 20 minutes at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 10 μL 5 × Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were boiled for 5 minutes and analyzed on 12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane before exposure for 2 hours at −80°C onto Kodak film. Signals on autoradiographies were quantified by using the Visio-Mic system (Genomic, Collonges-sous-Saleve, France). After decrease of radioactivity, PAK was quantified by immunoblot with anti-PAK1/2 antibody.

Statistical analysis

Results for flow cytometry experiments were expressed as mean ± SD and compared by using the Student ttest.

Results

Time course of actin polymerization and reorganization in activated platelets

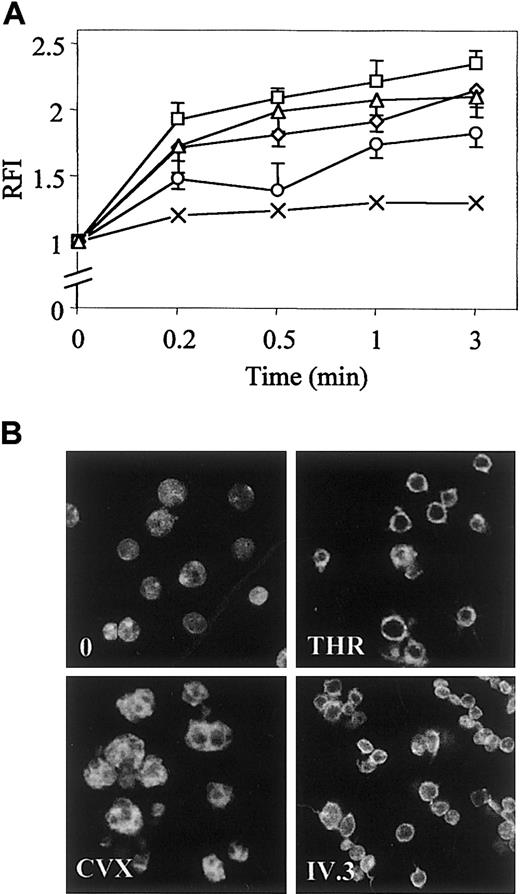

Phalloidin binding to polymerized actin during platelet shape change stimulated by optimal concentrations of various activators was quantified by flow cytometry analysis. Platelets were activated through PAR-1 receptor by thrombin (THR) or TRAP, through GpVI by CVX or ITAM-containing receptor FcγRIIA by monoclonal IV.3 antibody followed by stimulation of FcγRIIA clustering with antimouse IgG F(ab′)2. In the presence of THR (0.5 UI/mL), TRAP (10 μM), or IV.3 (2 μg/mL), the relative fluorescence emission intensity (RFI) was already maximal after 0.5 minutes of stimulation, although it reached its maximum after 1 minute of stimulation with CVX (250 pmol/L). THR, TRAP, IV.3, and CVX induced a 1.8-, 2.2-, 2.0-, and 1.7-fold increase of the content of polymerized actin after 1 minute of stimulation, respectively (Figure1A). Spatial organization of polymerized actin was visualized by confocal microscopy (Figure 1B). After stimulation for 1 minute with thrombin or IV.3, platelets emitted few thin and short filopodia, and actin was rearranged as a cortical ring under the plasma membrane that spread lamellae. CVX induced extensive platelet spreading as assessed by the presence of a marked ring of actin without evidence of filopodia. These results established that CVX specifically leads platelets to spread that clearly differ from the physiologic aspect of filopodia and lamellae.

Time course of actin polymerization and spatial reorganization in stimulated platelets.

(A) After stimulation with 0.5 UI/mL THR (⋄), 10 μM TRAP (■), 250 pmol/L CVX (○), 2 μg/mL monoclonal IV.3 antibody followed by clustering of FcγRIIA with 30 μg/mL antimouse IgG F(ab′)2 for an additional 1 minute (▵) or control immunoglobulin (×), platelets were fixed in 1.8% paraformaldehyde, labeled with 10 μM FITC-phalloidin in 0.02% Triton X-100 buffer, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as ratios of mean fluorescence intensity (RFI) of stimulated to resting platelets and reported as means (± SD) of RFI from at least 6 experiments. (B) Platelets stimulated for 1 minute were also analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (× 100). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Time course of actin polymerization and spatial reorganization in stimulated platelets.

(A) After stimulation with 0.5 UI/mL THR (⋄), 10 μM TRAP (■), 250 pmol/L CVX (○), 2 μg/mL monoclonal IV.3 antibody followed by clustering of FcγRIIA with 30 μg/mL antimouse IgG F(ab′)2 for an additional 1 minute (▵) or control immunoglobulin (×), platelets were fixed in 1.8% paraformaldehyde, labeled with 10 μM FITC-phalloidin in 0.02% Triton X-100 buffer, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as ratios of mean fluorescence intensity (RFI) of stimulated to resting platelets and reported as means (± SD) of RFI from at least 6 experiments. (B) Platelets stimulated for 1 minute were also analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (× 100). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Time course of Cdc42 and Rac1 activation after stimulation with thrombin, TRAP, CVX, or IV.3

Because of the role of Cdc42 and Rac1 in actin reorganization, we studied the level of Cdc42-GTP and Rac1-GTP during stimulation by thrombin, TRAP, CVX, or IV.3. We used the PAK1 binding domain in fusion with GST (PBD-GST) to trap Cdc42 and Rac1 in their GTP-bound form from the detergent-soluble fraction of platelets. In the presence of exogenously added GTPγS, full activation of Cdc42 or Rac1 was obtained. No residual Cdc42 or Rac1 was detected in the supernatants. In the presence of an excess of GDP, Cdc42 and Rac1, maintained in an inactive state, were unable to bind to PBD-GST beads and remained in the supernatants (Figure 2A). These results validate the specificity of PBD-GST beads for the detection of Cdc42-GTP and Rac1-GTP.

Activation of Cdc42 and Rac1 in platelets.

(A) Specific interaction of Cdc42-GTP or Rac1-GTP with PBD. Platelet lysates were incubated with 100 μM GTPγS or GDP and clarified before precipitation on PBD-GST beads. Supernatants (S) were separated from bead pellets (P) by centrifugation and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and specific immunoblotting (IB). (B) Time course of Cdc42 or Rac1 activation in stimulated platelets. After stimulation with 0.5 UI/mL THR (⋄), 10 μM TRAP (■), 250 pmol/L CVX (○), or 2 μg/mL monoclonal IV.3 antibody followed by 30 μg/mL antimouse IgG F(ab′)2 (▵), platelets were lysed in 1% NP-40 buffer. Pull-down of GTP-bound Cdc42 or Rac1 on PBD-GST beads was performed. (Upper panel) Representative anti-Cdc42 or anti-Rac1 immunoblots. (Lower panel) Quantification of Cdc42-GTP or Rac1-GTP expressed as mean ± SD of 3 separated experiments. (C) Expression of Cdc42 in cytoskeleton pellets (P) and NP-40–soluble supernatants (S) of CVX- or IV.3-stimulated platelets. NP-40–insoluble and –soluble fractions were separated by centrifugation (10 000g for 20 minutes at 4°C), and samples corresponding to 15 × 106 platelets were analyzed for Cdc42 expression by immunoblotting. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Activation of Cdc42 and Rac1 in platelets.

(A) Specific interaction of Cdc42-GTP or Rac1-GTP with PBD. Platelet lysates were incubated with 100 μM GTPγS or GDP and clarified before precipitation on PBD-GST beads. Supernatants (S) were separated from bead pellets (P) by centrifugation and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and specific immunoblotting (IB). (B) Time course of Cdc42 or Rac1 activation in stimulated platelets. After stimulation with 0.5 UI/mL THR (⋄), 10 μM TRAP (■), 250 pmol/L CVX (○), or 2 μg/mL monoclonal IV.3 antibody followed by 30 μg/mL antimouse IgG F(ab′)2 (▵), platelets were lysed in 1% NP-40 buffer. Pull-down of GTP-bound Cdc42 or Rac1 on PBD-GST beads was performed. (Upper panel) Representative anti-Cdc42 or anti-Rac1 immunoblots. (Lower panel) Quantification of Cdc42-GTP or Rac1-GTP expressed as mean ± SD of 3 separated experiments. (C) Expression of Cdc42 in cytoskeleton pellets (P) and NP-40–soluble supernatants (S) of CVX- or IV.3-stimulated platelets. NP-40–insoluble and –soluble fractions were separated by centrifugation (10 000g for 20 minutes at 4°C), and samples corresponding to 15 × 106 platelets were analyzed for Cdc42 expression by immunoblotting. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

In platelets stimulated by thrombin or TRAP, both Cdc42-GTP and Rac1-GTP accumulated from 0.2 minutes of stimulation. After FcγRIIA activation, Rac1 was also rapidly activated, although Cdc42-GTP was only transiently detected. The amount of Rac1-GTP increased slowly until 3 minutes following treatment by CVX, whereas activated Cdc42 was quite undetectable (Figure 2B, upper panel). Quantification by densitometry analysis shows that thrombin or TRAP induced a 2- or 3-fold increase of the amount of Cdc42-GTP and a 2.5- or 3.6-fold increase of the amount of Rac1-GTP, after 3 minutes. Both IV.3 and CVX were stimulated by the accumulation of Rac1-GTP (Figure 2B, lower panel). Although Cdc42 was present in the detergent-soluble supernatants and did not translocate efficiently to the cytoskeleton fraction (Figure 2C), less than a 1.5-fold increase or no increase of Cdc42-GTP was observed after FcγRIIA or GpVI activation, respectively. These results show that filopodia and subsequent lamellipodia formation induced by thrombin, TRAP, or IV.3 coincides with the activation of Cdc42 and Rac1. CVX that produces extensive lamellae only activates Rac1.

Activation of PAK

Direct binding of the GTP-bound form of Cdc42 and/or Rac1 to the regulatory domain of PAK resulted in the activation of the kinase.5 In an attempt to compare the amount of activated PAK in stimulated platelets, we used an in vitro phosphorylation assay, allowing the analysis of PAK autophosphorylation and kinase activity toward MBP as an exogenous substrate. As shown in Figure3A, thrombin (0.5 UI/mL), as well as TRAP (10 μM), CVX (250 pmol/L), or IV.3 (2 μg/mL) induced an efficient autophosphorylation of PAK and an increase in MBP phosphorylation, after 3 minutes of stimulation. Anti-PAK1/2 immunoblot showed that the amounts of immunoprecipitated PAK were equal.

Activation of PAK.

(A) PAK autophosphorylation and kinase activity in stimulated platelets. PAK was immunoprecipitated from platelets stimulated as indicated for 3 minutes at 37°C and incubated with 1 μg MBP in the presence of 20 μM MgCl2-ATP and 0.185MBq (5 μCi) γ[32P]-ATP. Autophosphorylated PAK was visualized as a 65-kDa phosphoprotein, and its kinase activity was evaluated by phosphorylation of MBP (pMBP). The amount of immunoprecipitated PAK was controlled by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblotting. (B) Time course of PAK activation in thrombin-stimulated platelets. Platelets were stimulated for 0 to 3 minutes at 37°C, and PAK activation was evaluated as in vitro kinase activity toward MBP. Total PAK (arrow) was quantified by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblotting (left). Autophosphorylation of PAK in THR-stimulated platelets (1 minute) detected by direct immunoblotting with anti-phosphoPAK1/2 Thr423/Thr402 (pPAK; right). (C) Quantification of PAK activity during the time course of thrombin stimulation by densitometry analysis. Results are expressed as a ratio of pMBP to total PAK and reported as means ± SEM of 3 separate experiments (*P < .05). Controls with rabbit irrelevant IgG is shown in lane C.

Activation of PAK.

(A) PAK autophosphorylation and kinase activity in stimulated platelets. PAK was immunoprecipitated from platelets stimulated as indicated for 3 minutes at 37°C and incubated with 1 μg MBP in the presence of 20 μM MgCl2-ATP and 0.185MBq (5 μCi) γ[32P]-ATP. Autophosphorylated PAK was visualized as a 65-kDa phosphoprotein, and its kinase activity was evaluated by phosphorylation of MBP (pMBP). The amount of immunoprecipitated PAK was controlled by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblotting. (B) Time course of PAK activation in thrombin-stimulated platelets. Platelets were stimulated for 0 to 3 minutes at 37°C, and PAK activation was evaluated as in vitro kinase activity toward MBP. Total PAK (arrow) was quantified by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblotting (left). Autophosphorylation of PAK in THR-stimulated platelets (1 minute) detected by direct immunoblotting with anti-phosphoPAK1/2 Thr423/Thr402 (pPAK; right). (C) Quantification of PAK activity during the time course of thrombin stimulation by densitometry analysis. Results are expressed as a ratio of pMBP to total PAK and reported as means ± SEM of 3 separate experiments (*P < .05). Controls with rabbit irrelevant IgG is shown in lane C.

The time course of PAK activation was followed in thrombin-stimulated platelets (Figure 3B, left). Quantification of pMBP to total PAK by densitometry analysis showed that MBP phosphorylation increased until 3 minutes (Figure 3C). The occurrence of PAK autophosphorylation in platelets stimulated by THR for 1 minute was confirmed by direct immunoblot with anti-pPAK1/2 (Thr423/Thr402) antibody (Figure 3B, right). These results demonstrate that platelet agonists induce an activation of PAK that correlates with activation of the GTPases.

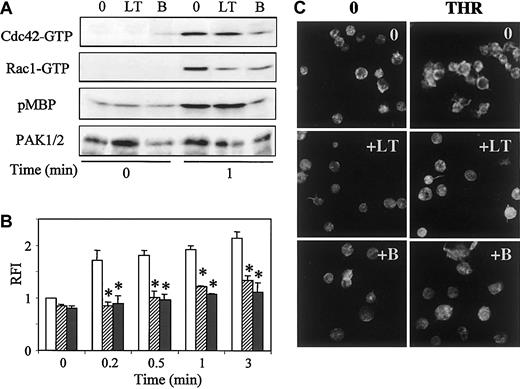

Inhibition of thrombin-induced activation of Cdc42/Rac1 blocks PAK activation

Considering that PAK activation by thrombin was linked to early and sustained activation of Cdc42 and Rac1, we investigated whether small G protein activation would be necessary for PAK activation. To test this hypothesis, we used membrane-permeable clostridial toxins to inactivate Cdc42 or Rac1. Large molecular weight cytotoxins (250-300 kDa) such as toxin B from C difficile and lethal toxin (LT) from C sordellii possess a glucosyltransferase activity, allowing glucosylation and, thus, inactivation of small G proteins. Indeed, toxin B and LT affect different intracellular target proteins. Toxin B has been reported to inactivate Rho, Rac, and Cdc42, whereas the targets of LT, isolated from strain IP-82, are p21Ras, Ral, Rap, and Rac proteins.22 23 Platelets pretreated or not with LT or toxin B were stimulated with thrombin, and, subsequently, the amounts of activated Cdc42, Rac1, and PAK were determined. We observed that the level of Rac1-GTP after a 1-minute stimulation with thrombin was decreased in platelets pretreated with LT compared with untreated cells. Toxin B was also found to efficiently reduce Rac1 activity. The activation of Cdc42 was decreased by a pretreatment with toxin B but not with LT. Phosphorylation of MBP was unaffected by the presence of LT, whereas toxin B did not permit the activation of PAK over the basal level (Figure 4A). A complete blockage of PAK activity results from a decrease of the amount of both Cdc42-GTP and Rac1-GTP. This finding suggests that full activation of both Cdc42 and Rac1 is required for stimulation of PAK activity.

Effects of LT or toxin B on Cdc42, Rac1, or PAK activation and actin reorganization induced by thrombin.

Prior to stimulation with thrombin for 1 minute, platelets were incubated or not with 1 μg/mL LT or toxin B for 2 hours at 37°C. (A) Pull-down of Cdc42-GTP or Rac1-GTP was performed on PBD-GST, and PAK kinase activity was tested by in vitro phosphorylation of MBP. Quantification of immunoprecipitated PAK was performed by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblot. (B,C) Platelets, preincubated with vehicle (open bars), LT (hatched bars), or toxin B (dark bars), were permeabilized and labeled with 10 μM FITC-phalloidin before analysis by (B) flow cytometry (mean ± SEM; *P < .05) or (C) confocal fluorescence microscopy (× 100). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Effects of LT or toxin B on Cdc42, Rac1, or PAK activation and actin reorganization induced by thrombin.

Prior to stimulation with thrombin for 1 minute, platelets were incubated or not with 1 μg/mL LT or toxin B for 2 hours at 37°C. (A) Pull-down of Cdc42-GTP or Rac1-GTP was performed on PBD-GST, and PAK kinase activity was tested by in vitro phosphorylation of MBP. Quantification of immunoprecipitated PAK was performed by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblot. (B,C) Platelets, preincubated with vehicle (open bars), LT (hatched bars), or toxin B (dark bars), were permeabilized and labeled with 10 μM FITC-phalloidin before analysis by (B) flow cytometry (mean ± SEM; *P < .05) or (C) confocal fluorescence microscopy (× 100). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Inhibition of Cdc42 and Rac1 blocks actin polymerization and shape change induced by thrombin

The effects of LT or toxin B were tested on the amount of polymerized actin in phalloidin-labeled platelets by flow cytometry. We observed that, whereas LT or toxin B had no significant effect on the content of preexisting polymerized actin in platelets at rest (time 0), they both inhibited early movements of actin after stimulation by thrombin (Figure 4B).

The distribution of polymerized actin was studied after treatment with toxin B or LT by confocal microscopy (Figure 4C). In unstimulated platelets, no obvious modification in platelet shape was observed after toxin B or LT treatment. After a 1-minute stimulation with thrombin, LT inhibited the aspect of spread platelets and prevented the formation of the cortical ring of polymerized actin. Toxin B also blocked actin rearrangement. These results indicate that activation of Cdc42 and/or Rac1 is necessary for thrombin-induced shape change.

Cortactin is constitutively associated with PAK and dissociated from PAK after thrombin stimulation

Cortactin is an ubiquitous cortical-actin binding protein highly present at the cell periphery, within membrane ruffles and lamellipodia.24 In Swiss 3T3 cells, it has been demonstrated that dominant-negative N17Rac1 blocks cortactin translocation to the membrane ruffles and that introduction of an active form of PAK1 stimulated this translocation.25 These observations suggest that translocation of cortactin is controlled by the Rac1/PAK pathway. Thus, we investigated whether cortactin would interact with PAK. In vitro pull-down experiments showed that cortactin associated with GST-PAKWT (full length) and not with the constitutively active mutant GST-PAKT423E in resting platelets. In addition, PAK associated with GST-cortactin (Figure5A). In vivo coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that cortactin was constitutively associated with PAK (Figure 5B, left) and, conversely, that PAK coimmunoprecipitated with cortactin in resting platelets (data not shown). Furthermore, cortactin dissociated from PAK after a 1-minute stimulation with thrombin. These results suggest that activated PAK, either the active mutant or the PAK activated by thrombin, loses its ability to bind cortactin. When platelets were incubated with toxin B, PAK autophosphorylation induced by thrombin was inhibited, and the binding of cortactin to PAK was restored (Figure 5C). This result confirms that the interaction of cortactin with PAK is regulated by PAK phosphorylation and that PAK activation causes cortactin dissociation.

Constitutive association of cortactin with PAK in resting platelets.

(A) In vitro association of PAK and cortactin. Pull-down experiments were performed from resting platelets on GST-fused proteins bound to Sepharose beads. The left immunoblots (IB) show the pull-down of cortactin on GST-PAKWT (full length) or GST-PAKT423E (active mutant). The right blots show the pull-down of PAK on GST-cortactin. Anti-GST immunoblots are shown as controls. (B) In vivo association of cortactin with PAK. (Left) Coprecipitation of cortactin with PAK in resting platelets and dissociation of cortactin after thrombin stimulation. PAK was immunoprecipitated from the detergent-soluble fraction of platelets stimulated with thrombin for 0, 0.2, or 1 minute at 37°C. Associated cortactin was revealed by immunoblotting. (Right) Effect of DNase I on the association of cortactin with PAK in resting platelets. Unstimulated platelet lysates were treated for 45 minutes at 37°C with 0 to 20 μM DNase I, and PAK was immunoprecipitated (IP). Cortactin and actin were revealed by specific immunoblot. Anti-PAK1/2 immunoblot is shown as a control of the amount of immunoprecipitated PAK. (C) Effect of toxin B (1 μg/mL for 2 hours at 37°C) on the association of cortactin with PAK. PAK activity was evaluated as an in vitro autophosphorylation assay, and associated cortactin was revealed by specific immunoblotting. Controls with irrelevant rabbit immunoglobulins are shown in lane C. Results are representative of 2 or 3 separate experiments.

Constitutive association of cortactin with PAK in resting platelets.

(A) In vitro association of PAK and cortactin. Pull-down experiments were performed from resting platelets on GST-fused proteins bound to Sepharose beads. The left immunoblots (IB) show the pull-down of cortactin on GST-PAKWT (full length) or GST-PAKT423E (active mutant). The right blots show the pull-down of PAK on GST-cortactin. Anti-GST immunoblots are shown as controls. (B) In vivo association of cortactin with PAK. (Left) Coprecipitation of cortactin with PAK in resting platelets and dissociation of cortactin after thrombin stimulation. PAK was immunoprecipitated from the detergent-soluble fraction of platelets stimulated with thrombin for 0, 0.2, or 1 minute at 37°C. Associated cortactin was revealed by immunoblotting. (Right) Effect of DNase I on the association of cortactin with PAK in resting platelets. Unstimulated platelet lysates were treated for 45 minutes at 37°C with 0 to 20 μM DNase I, and PAK was immunoprecipitated (IP). Cortactin and actin were revealed by specific immunoblot. Anti-PAK1/2 immunoblot is shown as a control of the amount of immunoprecipitated PAK. (C) Effect of toxin B (1 μg/mL for 2 hours at 37°C) on the association of cortactin with PAK. PAK activity was evaluated as an in vitro autophosphorylation assay, and associated cortactin was revealed by specific immunoblotting. Controls with irrelevant rabbit immunoglobulins are shown in lane C. Results are representative of 2 or 3 separate experiments.

In an attempt to determine whether the interaction between PAK and cortactin may depend on the state of actin polymerization, we incubated resting platelet lysates with increasing concentrations of DNase I that depolymerizes F-actin. DNase I forms a very tight 1:1 complex with G-actin, prevents interaction between myosin and G-actin, and blocks the dynamics of filament elongation.26 The level of cortactin that coprecipitated with PAK increased with the enhancement of DNase I concentration (Figure 5B, right). This finding suggests that only a fraction of cortactin is in association with PAK. Furthermore, it could not be excluded that the constitutive association of cortactin with PAK may be indirect because actin has been found to coimmunoprecipitate with these proteins.

In vitro phosphorylation of cortactin by PAK

In addition to efficient tyrosine phosphorylation by Src, it has been established that cortactin is also phosphorylated on serine or threonine residues. We performed in vitro phosphorylation assays with immunoprecipitated PAK in the presence of bacterially produced and purified recombinant cortactin. As shown in Figure6, recombinant cortactin was phosphorylated by thrombin-activated PAK, whereas it remained unphosphorylated when PAK was immunoprecipitated from resting platelets. This finding suggests that cortactin is an in vitro substrate for PAK.

In vitro phosphorylation of cortactin by PAK.

PAK was immunoprecipitated (IP) from platelets stimulated or not with THR (0.5 UI/mL) as indicated and incubated with 5 μg purified rHu cortactin in the presence of 20 μM MgCl2-ATP and 0.185MBq (5 μCi) γ[32P]-ATP. Phosphocortactin (pCortactin) was revealed by autoradiography. PAK was quantified by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblot (IB). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

In vitro phosphorylation of cortactin by PAK.

PAK was immunoprecipitated (IP) from platelets stimulated or not with THR (0.5 UI/mL) as indicated and incubated with 5 μg purified rHu cortactin in the presence of 20 μM MgCl2-ATP and 0.185MBq (5 μCi) γ[32P]-ATP. Phosphocortactin (pCortactin) was revealed by autoradiography. PAK was quantified by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblot (IB). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

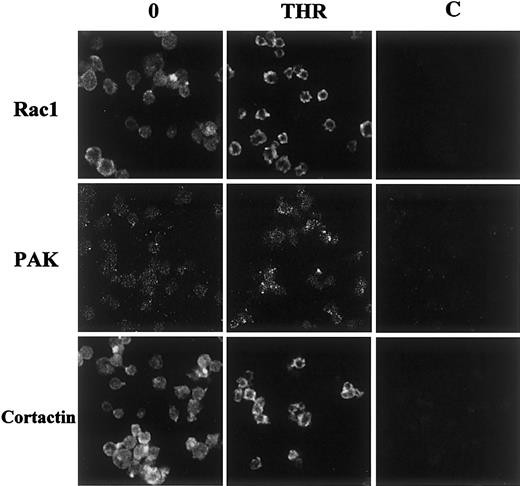

Immunolocalization of Rac1, PAK, and cortactin in thrombin-activated platelets

Because of the disruption of the interaction between PAK and cortactin after thrombin stimulation, we performed immunofluorescence studies to precise their subcellular localization. Rac1 and cortactin appeared homogeneously distributed in resting platelets. After stimulation, they moved to the submembrane region, forming a ring of fluorescence in the vicinity of lamellae and also invaded filopodia. PAK was sparsely distributed in resting platelets and focused near the membrane after stimulation. Similar results were obtained in TRAP-stimulated platelets. These results confirm that cortactin and PAK are differentially distributed throughout stimulated platelets and that both Rac1 and cortactin relocalize into lamellipodia (Figure7).

Immunolocalization of Rac1, PAK, and cortactin in thrombin-stimulated platelets.

Resting or stimulated platelets (0.5 UI/mL thrombin for 1 minute at 37°C) were fixed and labeled with 1-10 μg/mL anti-Rac1 MoAb, anti-PAK1/2 rabbit polyclonal antibody, or anti-cortactin monoclonal antibody for 30 minutes at 4°C. After washes in PBS (pH 7.40), samples were labeled with either secondary goat antimouse antibodies coupled to FITC or secondary goat antirabbit antibodies coupled to rhodamine. Samples were analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (×100). Controls with irrelevant mouse or rabbit IgGs are shown in (C). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Immunolocalization of Rac1, PAK, and cortactin in thrombin-stimulated platelets.

Resting or stimulated platelets (0.5 UI/mL thrombin for 1 minute at 37°C) were fixed and labeled with 1-10 μg/mL anti-Rac1 MoAb, anti-PAK1/2 rabbit polyclonal antibody, or anti-cortactin monoclonal antibody for 30 minutes at 4°C. After washes in PBS (pH 7.40), samples were labeled with either secondary goat antimouse antibodies coupled to FITC or secondary goat antirabbit antibodies coupled to rhodamine. Samples were analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (×100). Controls with irrelevant mouse or rabbit IgGs are shown in (C). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Discussion

In the present work, we show that lamellae spreading induced by thrombin, TRAP, monoclonal IV.3 antibody, or CVX correlates with the activation of PAK. Furthermore, inhibition of both Cdc42 and Rac1 with clostridial toxin B inhibits PAK activation by thrombin and platelet shape change. In resting platelets, the cortical actin-binding protein, cortactin, is constitutively associated with PAK, and the disruption of cortactin association with PAK is concomitant with the occurrence of lamellae spreading in response to thrombin. Inhibition of PAK activation by toxin B prevents the dissociation of cortactin.

Small G protein activation is commonly observed after ligand binding to heterotrimeric G protein–coupled receptors for bombesin or bradykinin or to tyrosine kinase receptors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and insulin receptors.1,2,27 In platelets, Cdc42 and Rac1 activation occurs after stimulation of G-coupled PAR-1 by TRAP or thrombin.4,28 Rac is also activated in response to collagen.28 Fcγ/FcγRIIA receptor-mediated phagocytosis in leucocytes requires Cdc42 and Rac activation,29,30 and we show, here, that the clustering of FcγRIIA, in platelets, increases the amount of Rac1-GTP and, in a lesser extent, Cdc42-GTP. In addition, we show that specific activation of the major receptor for collagen, GpVI, by CVX induces the activation of Rac1. Considering that Gq-coupled PAR-1 stimulates phospholipase C β (PLCβ) and that both FcγRIIA and GpVI implicate the tyrosine kinase Syk in the activation of PLCγ2.15,31 Rac activation, at least, is downstream of PLC activation and, consequently, on a raise of intracellular calcium, as suggested previously.28However, the mechanism of Rac activation is not unique. Rac activation through GpVI may require phosphatidylinositol 3′ (PI-3) kinase that is necessary for full activation of PLCγ2, although it is independent of PI-3 kinase after thrombin or TRAP.4,28 32Inhibition of Cdc42 and Rac1 by clostridial toxin B blocks thrombin-induced filopodia extension and lamellae spreading, confirming that they are events dependent on Cdc42 and Rac1.

PAK activity is also regulated through heterotrimeric G-coupled receptors, and, in platelets, PAK2 is activated by thrombin.6,13 In a recent paper, Suzuki-Inoue et al32 demonstrate that PAK, concomitantly with Rac, is activated during platelet spreading on immobilized collagen. This activation is dependent on integrin α2β1and possibly on GpVI. Here, we show that PAK is activated in response to TRAP, monoclonal IV.3 antibody, and the GpVI ligand, CVX. The activation of PAK by thrombin is dependent on Cdc42 and Rac1, because it is blocked when GTPases are inhibited by toxin B. It has been suggested that membrane relocalization of PAK strongly enhances its GTPase-dependent activation, for instance, in the neuronal PC12 cell line.33 This may increase its accessibility to high local concentrations of GTP-bound forms of Cdc42 and Rac1 and facilitates PAK autophosphorylation. It is interesting to note that PAK relocalizes near the platelet membrane (Figure 7) as well as Rac1 that moves to the edge of the cell.4 Thus, the subcellular localization of PAK may also be important for full activation in platelets.

For the first time, we show, here, that the cortical actin-binding protein, cortactin, is constitutively associated with PAK in resting platelets and that PAK autophosphorylation by thrombin correlates with the disruption of this interaction. Cortactin is an important regulator of actin filament polymerization. Recent evidence has been provided that cortactin colocalizes with F-actin and the Arp2/3 complex in lamellipodia structures, where it can promote the nucleation of new actin filaments, as demonstrated in proliferating NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and in MDA breast cancer cells with amplification of the gene at chromosome 11q13.34,35 In thrombin-stimulated platelets, cortactin translocates to the cytoskeleton fraction.36Furthermore, in Swiss 3T3 cells, cortactin is known to translocate from the cytosol to the F-actin at the membrane ruffles under the control of Rac1.25 Thus, cortactin relocalization in platelets could also be under the control of Rac1. Our present data suggest that the subcellular localization of a pool of cortactin is dependent on PAK activation. This suggestion is assessed by the fact that (1) cortactin is unable to associate with an active mutant of PAK in vitro, (2) a pool of cytosolic cortactin dissociates from PAK after activation of PAK by thrombin, and (3) dissociation is inhibited by inhibition of PAK autophosphorylation by toxin B. Furthermore, in the absence of PAK activation in resting platelets, the enhancement of the pool of unpolymerized actin after DNase I treatment also increases the pool of cortactin associated with PAK. Thus, the size of the pool of cytosolic cortactin stably associated with PAK may vary, depending on the degree of actin polymerization.

Cortactin is a well-known substrate for the tyrosine kinase Src.24 In a previous paper, we have shown that cortactin translocation to the detergent-insoluble cytoskeleton fraction could not be inhibited by the Src family kinase inhibitor PP2, suggesting that cortactin relocalization in the vicinity of F-actin may be independent of tyrosine phosphorylation.36 In addition, it has been shown that p85 cortactin is heavily charged with phosphate on serine and threonine residues.37 In colon carcinoma cells with cortactin gene amplification, p85 spontaneously relocalizes to the cell periphery at focal contacts with the matrix. Here, we show that bacterially produced recombinant cortactin is phosphorylated in vitro by thrombin-activated PAK and that cortactin colocalizes with Rac1 to the ring of actin filaments in lamellae, in the same conditions of stimulation. Taken together, these data suggest that the determinant for cortactin relocalization is rather a serine/threonine than a tyrosine phosphorylation. As previously published, the Nf2tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, is phosphorylated by PAK2. Unphosphorylated merlin localizes in the microvilli of the normal kidney epithelial cell line, LLC-PK1, although it relocalizes to larger membrane protrusions when phosphorylated.38 Thus, PAK is able to influence the subcellular localization of its substrates.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin by Src has been demonstrated to down-regulate its ability to bind F-actin in vitro.39However, the influence of serine/threonine phosphorylation on cortactin F-actin binding activity is not known. Interestingly, it has been recently shown that the intermediate filament protein, vimentin, when phosphorylated by PAK, loses its potential to form 10-nm filaments.40 In contrast, PAK phosphorylates and activates the LIM kinase that inhibits the activity of cofilin, an actin depolymerization factor, thus, facilitating actin polymerization.41 Whether serine/threonine phosphorylation of cortactin by PAK may influence its actin filament growth-promoting activity remains to be determined.

In conclusion, we show, in this work, that cortical actin reorganization in lamellae is supported by the Cdc42/Rac1/PAK pathway and is concomitant to the disruption of cortactin binding to PAK.

We thank Dr M. F. Carlier (CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France), Prof E. Cramer (Département d'Hématologie, Institut Cochin, Paris) for helpful discussions, F. Heutte for confocal microscopy, and A.-L. Roupie for assistance in manuscript preparation.

Supported by a fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (C.V.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Michaëla Fontenay-Roupie, Laboratoire d'Hématologie, Hôpital Cochin, 27, rue du Faubourg Saint-Jacques, F75679 Paris, Cedex 14, France; e-mail:fontenay@cochin.inserm.fr.

![Fig. 3. Activation of PAK. / (A) PAK autophosphorylation and kinase activity in stimulated platelets. PAK was immunoprecipitated from platelets stimulated as indicated for 3 minutes at 37°C and incubated with 1 μg MBP in the presence of 20 μM MgCl2-ATP and 0.185MBq (5 μCi) γ[32P]-ATP. Autophosphorylated PAK was visualized as a 65-kDa phosphoprotein, and its kinase activity was evaluated by phosphorylation of MBP (pMBP). The amount of immunoprecipitated PAK was controlled by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblotting. (B) Time course of PAK activation in thrombin-stimulated platelets. Platelets were stimulated for 0 to 3 minutes at 37°C, and PAK activation was evaluated as in vitro kinase activity toward MBP. Total PAK (arrow) was quantified by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblotting (left). Autophosphorylation of PAK in THR-stimulated platelets (1 minute) detected by direct immunoblotting with anti-phosphoPAK1/2 Thr423/Thr402 (pPAK; right). (C) Quantification of PAK activity during the time course of thrombin stimulation by densitometry analysis. Results are expressed as a ratio of pMBP to total PAK and reported as means ± SEM of 3 separate experiments (*P < .05). Controls with rabbit irrelevant IgG is shown in lane C.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/13/10.1182_blood.v100.13.4462/4/m_h82423531003.jpeg?Expires=1767735271&Signature=zhiHgMWlDeN88GDxY4TeRSU56-HfWjg-rL18ghvn6QUBK3IDIDMw25-W25elPtr3lrPmB76aTf0MAGFGsCgrfrmRxi8haB~mnn8EnHnZLkuwBtbGeTrBV67GZoKHaog6C3ketdDNCxjm4bTHPXVZ461f6yHo4-KNXrcK2rks6a1mPPbSlAtvVUjhLAHl1iA3PdoWEsCwKl~bf2XRldP0Gdh-toxM7groxbeIyIFM4xspQVydeSsP1dN0pXYTCR6p6XuEQA3lNzpLmVnLL8-15bWgPanb9AUgLgrWhbuNPmgW-~cmNqjo3Hewm359G5CqgTDuuO9P4bXwoSDTvld7zA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. In vitro phosphorylation of cortactin by PAK. / PAK was immunoprecipitated (IP) from platelets stimulated or not with THR (0.5 UI/mL) as indicated and incubated with 5 μg purified rHu cortactin in the presence of 20 μM MgCl2-ATP and 0.185MBq (5 μCi) γ[32P]-ATP. Phosphocortactin (pCortactin) was revealed by autoradiography. PAK was quantified by anti-PAK1/2 immunoblot (IB). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/13/10.1182_blood.v100.13.4462/4/m_h82423531006.jpeg?Expires=1767735271&Signature=307SgBXMNJ3j-J1D4cgATIPn~bkIz7Gd2yrVLJj8~HdMMu0LaMWi7e9zw~yG8ioaEfFggVYVcVOMKldU2poQiW01xubN7ZdajATyVqI4ZGBqGYlsiOfFkp4S3BCo4NOjW5HqgPKebIQpnUvY2uwuTC0SholhYpliUyOH8fycWvgVugeRVcZNUzbvuCRU-UDQ4osVv7kRZgBiyiJeIyCXfvJY6HRxml-QPMyypRKCWX9ZF9dngqJk6o4sUHXx6S7nLy2cCtR9Bn5EWWoE8T8M3liSodZmnae6wJ8GzNTX6Okr4~sHvZD1q~1yPeqTddB5M0~5schYJhNop2pgiYy67A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal