Abstract

To lower treatment-related mortality and toxicity of conventional marrow transplantation, a nonmyeloablative regimen using 200 cGy total-body irradiation (TBI) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) combined with cyclosporine (CSP) for postgrafting immunosuppression was developed. To circumvent possible toxic effects of external-beam γ irradiation, strategies for targeted radiation therapy were investigated. We tested whether the short-lived (half-life, 46 minutes) α-emitter bismuth 213 (213Bi) conjugated to an anti-CD45 monoclonal antibody (mAb) could replace 200 cGy TBI and selectively target hematopoietic tissues in a canine model of nonmyeloablative DLA-identical marrow transplantation. Biodistribution studies using iodine 123–labeled anti-CD45 mAb showed uptake in blood, marrow, lymph nodes, spleen, and liver. In a dose-escalation study, 7 dogs treated with the 213Bi–anti-CD45 conjugate (213Bi dose, 0.1-5.9 mCi/kg [3.7-218 MBq/kg]) without marrow grafts had no toxic effects other than a mild, reversible suppression of blood counts. On the basis of these studies, 3 dogs were treated with 0.5 mg/kg 213Bi-labeled anti-CD45 mAb (213Bi doses, 3.6, 4.6, and 8.8 mCi/kg [133, 170, and 326 MBq/kg]) given in 6 injections 3 and 2 days before grafting of marrow from DLA-identical littermates. The dogs also received MMF (10 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily the day of transplantation until day 27 afterward) and CSP (15 mg/kg orally twice daily the day before transplantation until 35 days afterward). The therapy was well tolerated except for transient elevations in levels of transaminases in 3 dogs, followed by, in one dog, ascites. All dogs had prompt engraftment and achieved stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism, with donor contributions ranging from 30% to 70% after more than 27 weeks of follow-up. These results will form the basis for additional studies in animals and later the design of clinical trials using213Bi as a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen with minimal toxicity.

Introduction

Allogeneic marrow transplantation provides a potential cure for a variety of hematologic and nonhematologic diseases. To avoid mortality and toxic effects associated with myeloablative marrow transplantation, a nonmyeloablative marrow transplantation regimen was developed in a canine model. The regimen uses 200 cGy total-body irradiation (TBI) before and administration of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) combined with cyclosporine (CSP) for immunosuppression after transplantation.1 The combination of MMF and CSP given after transplantation controlled not only graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) but was also found to be essential for maintenance of the donor graft (ie, control of host-versus-graft reaction). The results of the preclinical studies have been successfully translated into the clinic to treat elderly or medically infirm patients with hematologic malignant diseases who were not eligible to receive high-dose conventional grafts.2

Although the TBI dose used in these studies was low, there remains concern about the possible late toxic effects of γ radiation, especially in patients given transplants to treat nonmalignant diseases, eg, sickle cell disease. To reduce the risk of radiation toxicity, strategies to target radiation precisely to the marrow have been investigated.3,4 Studies with β-emitting radionuclides, particularly iodine 131 (131I), have shown the feasibility of this approach, first in an animal model5and later in clinical trials.6 However, β-particle–emitting radionuclides are not optimal for targeting hematopoietic cells because the range of the β particles (1-4 mm) is much greater than the diameter of the cells being targeted and dose rates are generally low.7 Thus, most of the energy is deposited away from the target cells. Consequently, high quantities of radioactivity are required and marked side effects are observed.

The α-emitting radionuclides8-10 are an attractive alternative to β-emitting radionuclides, particularly in targeting cells of the hematopoietic system.11 Importantly, α particles have very high energy (ie, 4-9 MeV) and deposit this energy over only a few cell diameters (ie, 40-90 μm). Owing to the high linear energy transfer (LET), α emitters are very cytotoxic, requiring only a few nuclear hits to induce cell death.12Although several preclinical studies have been conducted with antibody-targeted α-emitting radionuclides,11,13-18 the first clinical studies, which involve acute myeloid leukemia and glioblastoma multiforma as targets, began only recently.19 20

In the study reported here, an α-emitting radionuclide, bismuth 213 (213Bi), was coupled to an anti-CD45 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and used as conditioning for marrow transplantation in a canine model. 213Bi has a half-life (t1/2) of 46 minutes and is available from an actinium 225 (225Ac) generator system. The CD45 antigen was chosen to target hematopoietic tissues effectively because it is the most broadly expressed hematopoietic antigen and is not internalized or shed.21The anti-CD45 mAb was conjugated with the diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) derivative, cyclohexyl (CHX)–A",22 because this chelate provides efficient radiolabeling of 213Bi and has been shown to be stable in vivo.16,17 19 The data reported here indicate that the 213Bi–anti-CD45 conjugate can replace external-beam TBI in conditioning dogs for marrow transplantation.

Materials and methods

Dogs

Litters of beagles and minimongrel–beagle crossbreeds were either raised at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, WA) or purchased from other commercial kennels in the United States. The dogs were quarantined for 1 month and judged to be disease free before study. All were immunized against distemper, leptospirosis, hepatitis, papilloma virus, and parvovirus. The median weight of the dogs was 11.3 kg (range, 6.3-15.7 kg), and the median age was 24 months (range, 12-48 months). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center approved the experimental protocol. The study was performed in accordance with the principles outlined in the Guide for Laboratory Animals Facilities and Care of the National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council. The kennels were certified by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

The mAbs

For radiolabeling, we used the anti-CD45 mAb CA12.10C12 (IgG1).25 For flow cytometry, mAbs against canine CD45 (CA12.10C12; IgG1), CD4 (CA13.1.E4; IgG1),26 CD8 (CA9.JD3; IgG2a),26 and T-cell receptor (TCR)αβ (CA15.9D5; IgG1)27 were used. The anti-CD3 mAb CA17.6B3 (IgG2b) was provided by Dr Peter Moore (School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis). In addition, we used antibodies against canine CD44 (S5; IgG1)28 and canine myeloid cells (DM5; IgG1).29 The mAb 31A (IgG1) directed to mouse Thy-1 receptor (not cross-reactive with canine cells) was used as the irrelevant isotype control.30 These mAbs were produced and purified at the Biologics Production Facilities of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center as described previously.27 In addition, the commercially available antibodies against human CD14 (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA) cross-reacting with canine CD1431 and a goat antimouse (Fab′)2–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Biosource International) were used. The mAbs were either biotinylated or FITC conjugated according to standard protocols.

Conjugation of the anti-CD45 antibody with benzyl–CHX-A"–DTPA

The anti-CD45 mAb (CA12.10C12) was conjugated with the isothiocyanate form of the metal-binding chelate CHX-A"–DTPA after rigorous demetallation of the antibody, glassware, and solvents.22 In the demetallation, the anti-CD45 mAb (5 mg) was dialyzed by using a Slide-A-Lyzer 10K cassette (Pierce, Rockford, IL) against 1 L metal-free HEPES buffer, with a minimum of 5 buffer changes over 3 days at 4°C. All buffers used were prepared with metal-free (18 MΩ) water passed over a column of Chelex-100 resin (250 g/12 L). Five grams of Chelex-100 resin was added to each buffer change. The demetallated mAb was removed from dialysis and placed in an acid-washed microcentrifuge tube, and care was taken to ensure that no metals were introduced.

To 1.2 mL (31 nM) of the metal-free mAb (3.87 mg/mL) was added 30 μL (464 nM) isothiocyanatobenzyl–CHX-A" solution (22.4 mg/mL in dimethyl sulfoxide), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 18 hours. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was placed in a dialysis cassette, dialyzed against 3 × 1 L metal-free citrate buffer (50 mM sodium citrate, 150 mM sodium chloride [NaCl], and 0.05% sodium azide adjusted to pH 5.5) for 2 days and against 150 mM NaCl for 1 day and then stored at 4°C until used.

The number of chelates was evaluated by a spectrophotometric assay using yttrium–arsenazo III complex at 652 nm (1-4 chelates per protein).32 A single batch of antibody conjugated with CHX-A"–DTPA was prepared for all the studies in dogs, and the number of chelates per mAb for that batch was 3.6. Flow cytometry was conducted to compare the mAb–CHX-A" with the unconjugated antibody to determine whether the binding had been affected by conjugation.

Radiolabeling of the anti-CD45 mAb–CHX-A" conjugate with123I

The mAb–CHX-A" conjugate was labeled with 123I in 2 portions under comparable conditions. In the labelings, 125 μL sodium phosphate (0.5 M; pH 7.4) was added to 600 μL of a 1.31 mg/mL solution of mAb–CHX-A" conjugate in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To the resultant solution were added 30 μL 123I (6.4 or 6.9 mCi [237 or 255 MBq] in 0.1 N sodium hydroxide) and 75 μL of a 1 mg/mL solution of Chloramine-T in water. After 5 minutes at room temperature, the reaction was stopped with 7.5 μL of a 10 mg/mL solution of sodium metabisulfite in water. The reaction mixture was then placed on a PD-10 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and eluted in 1-mL fractions with PBS. Protein fractions (2 and 3) were combined to yield 3.3 mCi (122 MBq; 52%) and 3.22 mCi (119 MBq; 47%). The 2 products were combined, and 4.91 mCi (182 MBq) of this mixture was injected.

Radiolabeling of the mAb–CHX-A" conjugate with213Bi

The 225Ac nitrate was purchased on a column from the Department of Energy (Oak Ridge, TN). The 213Bi was obtained from 225Ac (t1/2, 10 days) by eluting the generator column with 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) with use of a dual-syringe pump system. As the elution proceeded, the213Bi-HCl solution was mixed with water (in a plastic chamber) and run across a MP-50 cation exchange column. The213Bi was trapped on the ion exchange column, and the column was removed from the generator system. The column was then eluted with 0.1 N hydrogen iodide, and the pH of the eluant was adjusted to 4.2 to 4.5 by using 3 M NH3OAc (Ultrex grade). A 200-μg quantity of the mAb–CHX-A" conjugate in saline was then mixed with the eluted 213Bi. After 2 to 5 minutes, the labeled antibody was purified on a size-exclusion column (PD-10). Labeling the mAb–CHX-A" with 213Bi was achieved in 80% to 95% (decay corrected) yields.

To determine the radiochemical purity, a small drop of the213Bi-labeled mAb–CHX-A" conjugate was analyzed by using instant thin-layer chromatography (ITLC) on an ITLC SG strip (Gelman, Ann Arbor, MI) and allowed to air dry. The dry ITLC strip was placed in a development chamber containing a small amount of 80% methanol and 20% 10 mM DTPA in water. When the solvent had nearly reached the top of the strip, it was air dried, cut in sections, and counted in a γ counter. The percentage of bound activity was obtained by dividing the activity in the first half of the strip (from point of spotting) by the total activity on the plate (× 100).

Flow cytometry

To assess antigen saturation with the 213Bi-labeled antibody and to quantitate the leukocyte subsets, either whole blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) prepared by Ficoll-Hypaque density-gradient centrifugation (density, 1.074) were used for analyses by flow cytometry.28 Then, 10 μg/mL of the respective FITC-conjugated mAb was added to 1 × 106 cells resuspended in 50 μL 15% horse serum (HS) and Hanks buffered salt solution (HBSS) or 50 μL whole blood. The suspension was incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes and washed once with cold HBSS supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated HS. If whole blood was used, red blood cells were lysed with a hemolytic buffer containing EDTA. The cells were washed 2 times, resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Pharmacokinetic studies

Saturation of the CD45 antigen by the injected mAb was assessed by flow cytometry. PBMCs were obtained from heparinized blood of study dogs before and at various intervals after mAb infusion and stained with anti-CD45 mAb directly conjugated to FITC or a goat antimouse (Fab′)2–FITC. Saturation was evaluated by comparing the fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with anti-CD45–FITC with that of goat antimouse (Fab′)2-FITC.

Plasma levels of the mAb were measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).33 Briefly, 96-well polyvinyl plates were coated with goat antimouse IgG and incubated with plasma from the infused dogs after blocking with 5% nonfat milk in PBS. Goat antimouse IgG horseradish peroxidase was used as the secondary antibody and 2,2′ azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) as the color reagent. Plates were read with a Vmax microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA) at 405 nm. Plasma obtained from dogs before infusion served as controls, and standard curves with known concentrations of mAb were established.

Mixed leukocyte cultures

To assess leukocyte function in mixed leukocyte cultures (MLCs) before and after transplantation,34 PBMCs from the dogs were resuspended in Waymouth medium supplemented with 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% l-glutamine and 20% heat-inactivated, pooled normal dog serum. Responder cells (1 × 105/well) and irradiated (2200 cGy) stimulator cells (1 × 105/well) were cocultured in triplicate in round-bottomed, 96-well plates for 6 days at 37°C in a humidified 5% carbon dioxide air atmosphere. In triplicates used as positive controls, 4 μg concanavalin was added to responder cells on day 3. On day 6, cultures were pulsed with 1 μCi (37 kBq) tritium-thymidine for 18 hours before harvesting. Tritium-thymidine uptake was measured as mean counts per minute for the 3 replicates by using a β-scintillation counter (Packard BioScience Company, Meriden, CT).

Natural killer cell cytotoxicity assay

To evaluate natural killer (NK) cell activity before and after transplantation, we conducted chromium-release assays.35PBMCs served as effectors, and cells from a canine thyroid adenocarcinoma cell line served as targets. Effector-to-target ratios of 60:1, 30:1, and 15:1 in triplicate wells were used. The percentage of cytotoxicity (percentage of specific lysis) was calculated by using the mean value of triplicate cultures: % specific lysis = [(experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release)] × 100. Spontaneous release was determined in wells with target cells and medium alone. Maximum release was determined in wells with target cells and 2% Triton X.

Biodistribution and dosimetry estimates

To assess the biodistribution, retention, and clearance of213Bi-labeled antibody and to estimate the radiation absorbed doses to major organs per unit of administered activity, one dog was injected with 4.9 mCi (181 MBq) 123I-labeled anti-CD45 mAb–CHX-A" conjugate. Because of difficulties in imaging213Bi, we used 123I to determine the pharmacokinetic parameters of the antibody. This was possible because the CD45 antigen is not internalized or shed and 213Bi is not released from the CHX-A" chelate in vivo. Blood samples were obtained from the dog at various times after injection and counted in a γ counter to evaluate the blood concentration and clearance over time of the 123I–anti-CD45 conjugate. These counts were corrected for decay, and percentages of the injected immunoconjugate dose per gram of blood were calculated.

Serial γ-camera images were also obtained of the whole body, liver, spleen, bladder, and marrow at 3 minutes and 1, 2, 3, and 20 hours after injection. For each organ, counts from the123I-labeled immunoconjugate were compared with the known standard, background counts were subtracted, and corrections were made for scatter and attenuation by tissue in the dog. To obtain precise measurements of the concentrations of 123I–mAb conjugate in the principal organs and tissues for cross-comparison with the γ-camera counts, the dog was euthanized 22 hours after injection and samples of each tissue were obtained, counted in a γ counter, and corrected for background and decay against a known standard. These data, together with measurements obtained from serial γ-camera images at early time points (3 minutes to 20 hours) were used to evaluate the concentrations of antibody and to construct time-activity curves for the whole dog and for its principal organs. These decay-corrected time-activity curves yielded biologic pharmacokinetic parameters for the antibody. The parameters were used to estimate the relevant uptake, retention, and clearance of 213Bi-labeled antibody.

The radiation absorbed dose was then calculated according to the following standard formula: D (absorbed dose, cGy) = 0.0512 E f Ao/m ∫ B(t) dt, where E is the average α energy (8.37 MeV), f is the fractional yield of α particles per decay (1.0), Ao is the initial activity of the organ (mCi, where 1 mCi = 37 MBq), m is the mass of the source organ (grams), and B(t) is the activity of the 213Bi in the tissue (integrated from time zero to infinity in units of mCi hours). We assumed complete energy absorption in the source organ and single-exponential retention and clearance of 213Bi over time to complete decay.

Dose-escalation study of 213Bi

A dose-escalation study was conducted in 7 dogs not given marrow grafts, after treatment with 213Bi-labeled anti-CD45 at increasing doses of radiation (0.1-5.9 mCi [3.7-218 MBq/kg]213Bi/kg) and various doses of antibody (Table1). The aim of the study was to evaluate hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic toxic effects of α radiation. For this purpose, daily peripheral blood samples were obtained to study changes in blood cell counts, hematopoietic cell saturation, cell subsets (flow cytometric analyses for CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, TCRαβ+, CD14+, CD45+, and myeloid cells [DM5+]), and results of kidney- and liver-function tests. The rates of decline and recovery of peripheral blood counts in the dogs were compared with those in historical controls given 200 and 300 cGy external-beam TBI, respectively,36 to estimate the dose equivalents of radiation delivered by 213Bi that resulted in comparable hematologic cytotoxicity. Starting with the fourth dog, a dose of unlabeled anti-CD45 mAb was injected first to prevent nonspecific tissue binding of the radiolabeled mAb. Nonspecific tissue binding was observed in previous studies with β-emitting radiolabeled mAbs and was easily corrected by adding unlabeled mAb, which reduced early hepatic uptake by up to 80%.37

Dogs given 213Bi without marrow grafts

| Dog . | Weight (kg) . | Anti-CD45 mAb (mg/kg) . | 213Bi (mCi/kg) . | [MBq/kg] . | “Cold” mAb (mg/kg) . | No. of injections . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E543 | 15.7 | 0.1 | 0.10 | [3.7] | None | 1 |

| E462 | 13.7 | 0.1 | 0.17 | [6.3] | None | 2 |

| E492 | 10.3 | 0.1 | 0.68 | [25] | None | 2 |

| E194 | 12.0 | 1.0 | 1.9 | [70] | 0.125 | 6 |

| E553 | 11.3 | 0.4 | 2.1 | [78] | 0.022 | 6 |

| E533 | 12.5 | 0.5 | 3.7 | [137] | 0.056 | 6 |

| E521 | 11.1 | 0.6 | 5.9 | [218] | 0.05 | 6 |

| Dog . | Weight (kg) . | Anti-CD45 mAb (mg/kg) . | 213Bi (mCi/kg) . | [MBq/kg] . | “Cold” mAb (mg/kg) . | No. of injections . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E543 | 15.7 | 0.1 | 0.10 | [3.7] | None | 1 |

| E462 | 13.7 | 0.1 | 0.17 | [6.3] | None | 2 |

| E492 | 10.3 | 0.1 | 0.68 | [25] | None | 2 |

| E194 | 12.0 | 1.0 | 1.9 | [70] | 0.125 | 6 |

| E553 | 11.3 | 0.4 | 2.1 | [78] | 0.022 | 6 |

| E533 | 12.5 | 0.5 | 3.7 | [137] | 0.056 | 6 |

| E521 | 11.1 | 0.6 | 5.9 | [218] | 0.05 | 6 |

213Bi indicates bismuth 213; and mAb, monoclonal antibody.

DLA-identical marrow grafts

On the basis of the results of the dose-escalation studies, we chose a total dose of 0.5 mg/kg anti-CD45 mAb administered in 6 injections on days 3 to 2 before grafting, as appropriate for transplantation studies. Three dogs received total doses of 3.6, 4.6, and 8.8 mCi/kg (133, 170, and 326 MBq/kg) 213Bi-labeled anti-CD45 mAb. On day 0, the dogs were given marrow grafts intravenously (mean, 4.7 × 108 mononuclear cells/kg) from their DLA-identical littermates (Table2). MMF (10 mg/kg given subcutaneously twice daily on days 0 to 27) and CSP (15 mg/kg given orally twice daily on the day before grafting until day 35 afterward) were administered to provide postgrafting immunosuppression.1 Supportive care was given after transplantation as described previously.38Hematopoietic engraftment was determined by recovery of peripheral blood granulocyte and platelet counts after the postirradiation nadirs. Donor and host cell chimerism was assessed by using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based assay of polymorphic (CA)ndinucleotide repeats.39 Digitalized images of the PCR gels were obtained by using the storage phosphorimaging technique.40 This allowed estimation of the proportion of donor-specific DNA among host DNA from digitalized gel pictures with use of image-analyzing software (ImageQuant; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The densities of the donor (D)–specific band and the host (H)–specific band were added as total (T) events (T = D + H). The percentage of donor-origin DNA was calculated as (D)/(T) × 100%. This technique allowed detection of 2.5% to 97.5% donor cell chimerism.1

Dogs given 213Bi-anti-CD45 mAb (0.5 mg/kg) and DLA-identical marrow grafts

| Dog . | Weight (kg) . | Anti-CD45 mAb (mg/kg) . | 213Bi (mCi/kg) . | [MBq/kg] . | Marrow MNCs (× 108/kg) . | GVHD . | Donor chimerism in MNCs (% range) . | Survival (wk)* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E889 (R) | 10.8 | 0.5 | 4.6 | [170] | 5.3 | No | 30-70 | > 39 |

| E886 (D) | ||||||||

| E805 (R) | 11.2 | 0.5 | 3.6 | [133] | 4.4 | No | 40-50 | > 39 |

| E806 (D) | ||||||||

| E885 (R) | 6.3 | 0.5 | 8.8 | [326] | 4.5 | No | 40-95 | > 27 |

| E893 (D) |

| Dog . | Weight (kg) . | Anti-CD45 mAb (mg/kg) . | 213Bi (mCi/kg) . | [MBq/kg] . | Marrow MNCs (× 108/kg) . | GVHD . | Donor chimerism in MNCs (% range) . | Survival (wk)* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E889 (R) | 10.8 | 0.5 | 4.6 | [170] | 5.3 | No | 30-70 | > 39 |

| E886 (D) | ||||||||

| E805 (R) | 11.2 | 0.5 | 3.6 | [133] | 4.4 | No | 40-50 | > 39 |

| E806 (D) | ||||||||

| E885 (R) | 6.3 | 0.5 | 8.8 | [326] | 4.5 | No | 40-95 | > 27 |

| E893 (D) |

213Bi indicates bismuth 213; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MNCs, mononuclear cells; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; R, recipient; and D, donor.

All dogs were euthanized on completion of the study.

At the completion of the study, the dogs were euthanized and complete autopsies, including histologic examinations, were performed to assess marrow engraftment, GVHD, hematopoietic recovery, and possible toxic effects.

Results

Imaging, biodistribution, and dose estimation using123I–anti-CD45

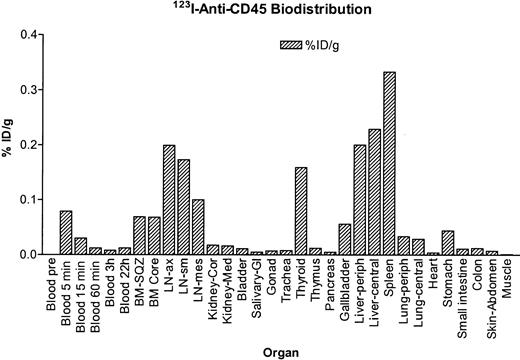

Dog E510 was injected with 123I-labeled anti-CD45 mAb–CHX-A" conjugate, and serial images were obtained with a γ camera. The blood clearance findings for the123I–anti-CD45 conjugate are shown in Figure1. A rapid clearance presumably due to rapid binding of circulating mAb to cellular CD45 was noted in the first 3 hours after injection. To standardize the quantification from the γ-camera images, the dog was euthanized and samples from organs were counted. As was observed in the images, the highest uptake was obtained in blood, marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, and liver (Figure2). From the data obtained, time-activity curves were prepared for the radiolabeled mAb conjugate, and the uptake, retention, and clearance of 213Bi-labeled mAb conjugate were estimated. The absorbed radiation doses for principal organs were calculated from the data. Among the nontarget organs, the liver received the highest dose, which was estimated to be 3.3 cGy/mCi.

Blood clearance of the 123I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate.

Clearance of 123I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate from blood after injection in dog E510, measured as percentage of injected dose (ID) per gram of blood.

Blood clearance of the 123I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate.

Clearance of 123I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate from blood after injection in dog E510, measured as percentage of injected dose (ID) per gram of blood.

Biodistribution of the 123I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate.

Tissue concentration of 123I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate in dog E510 at 22 hours after injection, measured as percentage of injected dose (ID) per gram of tissue.

Biodistribution of the 123I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate.

Tissue concentration of 123I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate in dog E510 at 22 hours after injection, measured as percentage of injected dose (ID) per gram of tissue.

Dose-escalation study of 213Bi–anti-CD45

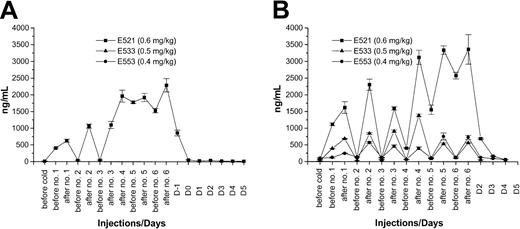

Seven dogs received injections of 0.1 to 5.9 (3.7-218 MBq/kg) mCi/kg 213Bi-labeled anti-CD45 (Table 1). The first 3 dogs received one injection with 0.1 mg/kg mAb labeled with 0.10 mCi/kg (3.7 MBq/kg), 0.17 mCi/kg (6.3 MBq/kg), and 0.68 mCi/kg (25 MBq/kg)213Bi, respectively. No significant effects on peripheral blood counts were observed (data not shown). Because CD45 antigen saturation was not achieved at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg mAb, the fourth dog was given 1.0 mg/kg mAb divided into 6 injections on days 3 and 2 before transplantation with a total of 1.9 mCi/kg (70 MBq/kg)213Bi. Saturation of the CD45 antigen on hematopoietic cells was observed by the fourth of the 6 injections (Figure3A). Therefore, 3 other dogs were subsequently given 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6 mg/kg mAb divided in 6 injections and labeled with 2.1, 3.7, and 5.9 mCi/kg (78, 137, and 218 MBq/kg)213Bi, respectively. Antigen saturation was not reached with 0.4 to 0.5 mg/kg mAb. However, with a dose of 0.6 mg/kg mAb, antigen saturation was again reached after 4 injections (Figure 3B). The injections were well tolerated, with no observable side effects. In these last 4 dogs, distinct declines in peripheral blood counts were observed.

Plasma concentration of 213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate.

Plasma concentration as determined by ELISA of213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate before and after each injection. (A) Findings in dog E194, which received a total of 1.0 mg/kg anti-CD45 mAb. (B) Plasma concentrations in the 3 subsequent dogs, which received between 0.4 and 0.6 mg/kg of the mAb without reaching antigen saturation with 0.4 to 0.5 mg/kg.

Plasma concentration of 213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate.

Plasma concentration as determined by ELISA of213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate before and after each injection. (A) Findings in dog E194, which received a total of 1.0 mg/kg anti-CD45 mAb. (B) Plasma concentrations in the 3 subsequent dogs, which received between 0.4 and 0.6 mg/kg of the mAb without reaching antigen saturation with 0.4 to 0.5 mg/kg.

To estimate the corresponding TBI dose equivalent to the administered antibody-targeted radiation dose, blood cell changes in historic control dogs treated with 200 and 300 cGy external-beam γ TBI without marrow rescue36 were compared with those in the 4 dogs treated with 1.9 to 5.9 mCi/kg (70-218 MBq/kg)213Bi–anti-CD45 (Figure 4). In dogs E194 and E553, the nadirs were less pronounced because they received a lower dose of radiation (1.9 and 2.1 mCi/kg (70 and 78 MBq/kg), respectively), with early antigen saturation in E194. In E533 and E521, neutropenia (neutrophil count < 0.5 × 109/L) was observed between days 6 and 16. The declines in the peripheral granulocyte counts were steeper and occurred earlier in the 213Bi-treated dogs. From these comparisons, we estimated the radiation dose of 3.7 to 5.9 mCi/kg (137-218 MBq/kg) 213Bi delivered to the marrow to be equivalent to 200 to 300 cGy external-beam (cobalt 60) TBI.

Comparison of peripheral blood granulocyte counts after TBI and radioimmunotherapy.

Granulocyte counts in 4 dogs given the anti-CD45 mAb (0.4-1.0 mg/kg) coupled to 1.9 to 5.9 mCi (70-218 MBq/kg) 213Bi/kg without marrow rescue compared with granulocyte counts in control dogs given 200 cGy external-beam γ TBI (A) and control dogs given 300 cGy TBI without marrow rescue (B).36

Comparison of peripheral blood granulocyte counts after TBI and radioimmunotherapy.

Granulocyte counts in 4 dogs given the anti-CD45 mAb (0.4-1.0 mg/kg) coupled to 1.9 to 5.9 mCi (70-218 MBq/kg) 213Bi/kg without marrow rescue compared with granulocyte counts in control dogs given 200 cGy external-beam γ TBI (A) and control dogs given 300 cGy TBI without marrow rescue (B).36

DLA-identical marrow grafts

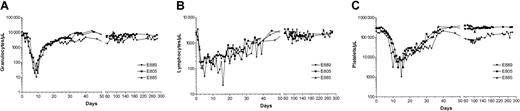

On the basis of the results of the dose-escalation studies, we targeted a 213Bi dose of more than 4 mCi/kg (148 MBq/kg) labeled to 0.5 mg/kg anti-CD45 mAb for the marrow transplantation studies. Three dogs received 3.6, 4.6, and 8.8 mCi/kg (133, 170, and 326 MBq/kg) 213Bi-labeled anti-CD45 mAb, respectively, followed by DLA-identical marrow grafts. Table 2 shows the results of the allogeneic marrow transplantations. Antigen saturation was not reached, as indicated by flow cytometry and ELISA assays (data not shown). The granulocyte nadirs were reached by days 4 to 5 after transplantation, with 10 to 30 granulocytes/μL. Thrombocytopenia (< 20 × 109/L platelets) occurred between days 5 and 22, necessitating 1 to 3 platelet transfusions in each dog. The dogs had a rapid hematopoietic recovery, with neutrophil counts above 0.5 × 109/L on days 7 to 9 (Figure5).

Peripheral blood granulocyte, lymphocyte, and platelet counts in dogs treated with nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation.

Counts of granulocytes, lymphocytes, and platelets in the 3 dogs treated with 0.5 mg/kg 213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb conjugated to 4.6 to 8.8 mCi/kg (170-326 MBq/kg) 213Bi.

Peripheral blood granulocyte, lymphocyte, and platelet counts in dogs treated with nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation.

Counts of granulocytes, lymphocytes, and platelets in the 3 dogs treated with 0.5 mg/kg 213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb conjugated to 4.6 to 8.8 mCi/kg (170-326 MBq/kg) 213Bi.

All 3 dogs showed mixed hematopoietic chimerism in peripheral blood as early as 2 to 3 weeks after transplantation. Figure6 illustrates the treatment regimen, peripheral blood cell changes, and results of microsatellite marker studies in one representative dog. The mixed chimerism was stable in all dogs, with values for donor cells ranging from 30% to 60% through the end of study. Quantitation of the T-cell, granulocyte, and monocyte recoveries by flow cytometry showed rapid return to pretransplantation levels by day 50. The dogs also had normal T-cell and NK cell functions as measured by MLCs and NK assays within 2 months after transplantation (Figure 7). There were no observable acute toxic effects during injection of the radioimmunoconjugate.

Nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation with213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb and MMF-CSP.

Treatment scheme, hematologic values, and microsatellite marker studies of chimerism in dog E889, which was given a transplant of marrow from the DLA-identical littermate E886 after conditioning with 4.6 mCi/kg (170 MBq/kg) 213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb and MMF-CSP for posttransplantation immunosuppression.

Nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation with213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb and MMF-CSP.

Treatment scheme, hematologic values, and microsatellite marker studies of chimerism in dog E889, which was given a transplant of marrow from the DLA-identical littermate E886 after conditioning with 4.6 mCi/kg (170 MBq/kg) 213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb and MMF-CSP for posttransplantation immunosuppression.

NK assay and MLC of sample from dog E889.

(A) Cytotoxicity is expressed as percentage of specific lysis for the NK assay. For the MLC, tritium-thymidine uptake was measured as mean counts per minute of triplicates before transplantation (B) and 34 days afterward (C).

NK assay and MLC of sample from dog E889.

(A) Cytotoxicity is expressed as percentage of specific lysis for the NK assay. For the MLC, tritium-thymidine uptake was measured as mean counts per minute of triplicates before transplantation (B) and 34 days afterward (C).

No signs of GVHD were observed. The transplants were clinically well tolerated, but reversible elevations in plasma levels of liver enzymes, especially alkaline phosphatase (AP) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), occurred in 2 dogs (E889 and E805) between days 40 and 100, without any clinical abnormalities in liver function (Figure8). In all dogs, the values for bilirubin and creatinine remained normal throughout the transplantation (data not shown). In the dog given the highest dose of 213Bi (E885), a different pattern was observed, with marked elevations in AP, ALT, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels after day 120 and development of ascites and signs of liver failure. On day 163, liver ultrasonography and liver biopsy were performed. On ultrasound assessment, the liver appeared very small, and a decreased portal venous flow velocity suggested portal hypertension. The liver biopsy showed no histologic abnormality apart from slight signs of sinusoidal fibrosis. Because of intractable ascites, the dog was euthanized on day 191. The autopsy showed a very small, though macroscopically normal liver. Histologic examination showed signs of marked periportal fibrosis, irregular sinusoidal fibrosis, and Kupffer cell aggregates.

Liver-enzyme levels in dogs treated with nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation.

Shown are values for AP, AST, ALT, and γ-glutamyltransferase in the 3 dogs given transplants and the 213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate.

Liver-enzyme levels in dogs treated with nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation.

Shown are values for AP, AST, ALT, and γ-glutamyltransferase in the 3 dogs given transplants and the 213Bi–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate.

At the end of the study (days 277 and 279), the remaining 2 dogs (E889 and E805) were euthanized and extensive autopsies performed. No abnormalities, including no signs of GVHD, were found.

Discussion

The aim of these studies was to replace external-beam γ TBI with radioimmunotherapy with 213Bi in a canine model of nonmyeloablative marrow transplantation. Studies of biodistribution of the 213Bi–anti-CD45 conjugate demonstrated that this construct is able to target hematopoietic tissues selectively. In a dose-escalation study, a dose of the radioimmunoconjugate equivalent to 200 to 300 cGy TBI was determined. In ensuing experiments with allogeneic marrow grafting after conditioning with the213Bi–anti-CD45 conjugate and posttransplantation immunosuppression using MMF and CSP, we demonstrated that this regimen allowed stable, long-term engraftment of DLA-identical marrow from littermates.

Several β-emitting radioisotopes have been investigated for radioimmunotherapy in the conditioning for marrow transplantation. Studies in mice and macaques using 131I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugates found that this construct can deliver radiation specifically to hematopoietic tissue. This targeted delivery of radiation resulted in 2 to 3 times more radiation delivered to the marrow, up to 12 times more to the spleen, and 2 to 8 times more to the lymph nodes compared with the liver, lungs, or kidneys.5,41 Successful clinical trials using this 131I–anti-CD45 mAb conjugate in addition to TBI in HLA-matched, related allogeneic or autologous marrow transplantation in patients with acute leukemias or myelodysplastic syndromes followed.6 A similar approach used rhenium 188–labeled anti-CD66 combined with 1200 cGy TBI or busulfan and high-dose cyclophosphamide with or without thiotepa in autologous or allogeneic marrow grafting in patients with acute myeloid leukemias or myelodysplastic syndromes.42 These studies demonstrated the feasibility of selectively targeting the hematopoietic system with radioimmunotherapy, although always in combination with conventional external-beam irradiation. Ruffner et al43 showed in a mouse model that 131I–anti-CD45 conjugate can replace a substantial part of, but not all TBI, delivering a biologic equivalent to 800 cGy TBI. Rather than attempting to optimize the use of β-emitting radionuclides in marrow-conditioning regimens, we thought it reasonable to study the use of α-emitting radionuclides in radioimmunotherapy to replace the 200 cGy TBI in the current nonmyeloablative regimen.

We chose to investigate the use of α-emitting radionuclides because they offer several physical characteristics that could make them superior to the previously employed β-emitting radionuclides in targeting hematopoietic cells. An α particle has an energy of 5 to 8 MeV delivered within a 40- to 80-μm radius, thereby limiting the effective treatment to several cell diameters and minimizing nonspecific irradiation of surrounding tissues. The high LET and the limited ability of cells to repair DNA damage from α radiation account for the high relative biologic effectiveness and cytotoxicity of α particles. For example, at doses of 100 to 200 cGy, α radiation may be 5 to 100 times more effective than γ or β radiation.11 The α-emitting radionuclide we chose was213Bi. This radionuclide has a t1/2 of 46 minutes, 8.35 MeV energy, a maximum range of 81 μm, and a LET of 102 keV/μm.13 It is commercially available in a225Ac-213Bi generator system.8Only a few preclinical studies have compared the efficacy and toxicity of β and α emitters in a mouse model, and they demonstrated a favorable profile for 213Bi compared with yttrium 90 (90Y).44,45 Despite these advantages, there are certain limitations to the use of 213Bi, particularly its limited availability and high cost. Also, its short t1/2 makes its use logistically challenging. In addition, the issue of possible carcinogenicity needs further evaluation.46

We selected CD45 as the target antigen because it is the most widely expressed antigen on malignant and nonmalignant hematopoietic tissues and it has a high density on hematopoietic cell surfaces.47,48 About 200 000 copies of the CD45 antigen are expressed on the average circulating leukocyte. This high antigen density is important because it permits the use of readily achievable specific activities of antibodies labeled with the short half-lived213Bi. CD45 is a tyrosine phosphatase that is critical for activation mediated by T- and B-cell antigen receptors, and it is expressed on all leukocytes, including their precursors in the marrow.21,49 Our data on the biodistribution of CD45-targeted radiation in dogs when using an 123I–CD45 radioimmunoconjugate are consistent with the results of Matthews et al5 41 showing a very high uptake of the radioimmunoconjugate in blood, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and spleen. Among nontarget organs, the liver received the highest dose, probably because of nonspecific uptake of the radioimmunoconjugate by Kupffer cells.

The efficacy and toxicity of the radioimmunoconjugate are highly influenced by the labeling technique used. The conjugates must be thermodynamically stable and kinetically inert to avoid deposition of radiobismuth in the kidney or other nontarget organs. The very short t1/2 of 213Bi and its highly energetic α-particle emission limit the methods used for radiolabeling. In previous studies, DTPA chelates that incorporated a CHX group in their structure produced conjugates that were labeled rapidly and were resistant to release of radiobismuth in vivo.45,50-52Because of these results, we chose to use the CHX-A"–DTPA22 conjugate for our studies. Reliable and stable labeling of mAbs with indium 111, 90Y,212Bi, and 213Bi can be performed by using the CHX-A"–DTPA chelator.45 50-53 With this method, we have conducted more than 100 labelings, obtaining 85% to 93% decay-corrected isolated yields within 30 minutes.

Multiple factors, including antigen distribution, antibody dose, labeled radiation activity, and nonspecific tissue binding influence the in vivo pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. To best account for the numerous variables present, we conducted in vivo dose-escalation studies. First, an antibody dose targeting enough antigens to deliver the necessary irradiation effectively without reaching antigen saturation (to prevent the circulation of unbound radiolabeled antibody) had to be determined. After dose-escalation studies, we chose a dose of 0.5 mg/kg CD45 mAb for further experiments. With this amount of mAb, a radiation dose corresponding to 200 to 300 cGy TBI (determined by comparing hematology data from treated dogs with findings in historic controls36 treated with TBI) could be administered. Of note, there were steeper declines in blood counts in the 213Bi-treated dogs, presumably because of the immediate elimination of all targeted cells without sparing already committed peripheral progenitor cells. These results are in contrast to those with external-beam photon irradiation, after which certain hematopoietic precursor cells might still be able to mature and appear in the circulating blood, thereby delaying the decline in peripheral blood counts.

To determine whether radioimmunotherapy with the described213Bi–anti-CD45 conjugate can replace TBI in the nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, we performed marrow-transplantation studies in 3 dogs. Stable and rapid engraftment occurred in all 3 dogs, with mixed chimerism levels ranging from 30% to 70% donor cells after 1 month. In all dogs, this level of chimerism was sustained through the end of study, although only a short course of immunosuppression therapy with MMF and CSP (28 and 37 days, respectively) was administered. The nadirs of platelet and neutrophil counts were lower than observed in dogs treated with 200 cGy TBI.1 The immune reconstitution evaluated by peripheral blood CD4+, CD8+, TCR+, granulocyte, and monocyte counts was rapid, with neutrophil levels above 0.5 × 109/L by day 8, platelet levels above 20 × 109/L by day 17, and pretransplantation T-cell levels reached after one month.

The treatment was clinically well tolerated, with no signs of hypersensitivity or other immediate side effects. The only possible toxic effects we observed were a transient elevation in liver-enzyme levels in 2 dogs and an elevation in liver-enzyme levels in conjunction with ascites in one dog. In dogs given transplants after conditioning with 200 cGy TBI only, no similar pattern of liver-enzyme alteration was observed, suggesting that this toxic effect was due to the radioimmunotherapy.1 Liver biopsies in the dog with ascites showed subtle signs of sinusoidal fibrosis, findings that were not sufficient to explain portal hypertension. On autopsy, the liver was found to be very small but macroscopically normal, with marked periportal and sinusoidal fibrosis on histologic examination. In the preclinical and clinical studies with 213Bi radioimmunoconjugates reported thus far, mild liver toxicity with transient increases in levels of transaminases was observed.54 In contrast, studies in mice showed renal and bone marrow toxic effects to be dose limiting.44,52 We did not observe any signs of renal toxicity, despite the potentially high avidity of free, unbound bismuth for the kidneys in the dogs treated with the radioimmunoconjugate, a result that reflects the high in vivo stability of the construct. This is consistent with findings by other investigators who used this bifunctional chelating agent for in vivo sequestration of bismuth isotopes.22,50,52 55

Because the liver was the nontarget organ that received the highest dose of radiation, the elevation in liver-enzyme levels could have been a sign of transient radiation damage to this organ. CD45 is not expressed on hepatocytes, but abundant cells of hematopoietic origin in the liver do express CD45, for example, Kupffer cells56(monocyte lineage) and circulating leukocytes, which comprise up to 20% of nonparenchymal cells.57 In addition, circulating immunoglobulins are nonspecifically taken up in the liver by Kupffer cells and endothelial cells, and this could lead to an increased radiation dose.58 Recently, a sinusoidal obstruction syndrome characterized by portal hypertension and intense sinusoidal fibrosis has been observed in patients after treatment with gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg; Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals, Madison, NJ), an anti-CD33–toxin conjugate.59,60 The histologic findings in the liver in these clinical cases were similar to the sinusoidal fibrosis in the dog in our study that was given the highest dose of radiation. The time from radiation exposure to signs of liver injury in our dogs was more than 30 days, suggesting not direct hepatocyte toxicity but activation of stellate cells, sinusoidal obstruction, and ischemic hepatocyte injury.61 Mechanisms possibly involved in this pathologic process are increased activity of matrix metalloproteinases and glutathione depletion.62Studies in animals demonstrated successful use of metalloproteinase inhibitors and glutathione to prevent such hepatic veno-occlusive disease.63-65 These agents could be of use in preventing the liver toxicity observed in the dogs in our study.

Previous studies have shown that the efficacy of radioimmunotherapy is influenced largely by the radionuclide used, the affinity of the antibody to the target antigen, the tissue distribution of the antigen, and the vascularization of the target tissue.11,66,67Given these prerequisites, radioimmunotherapy of hematopoietic tissue using an α emitter may provide greater efficacy than dose-equivalent external-beam radiation. The only clinical trial conducted thus far in which 213Bi as an α emitter was used in the treatment of myeloid leukemia used substantially lower amounts of activity labeled to the mAb—0.28 to 1.0 mCi/kg (10-37 MBq/kg)—whereas up to 8.8 mCi/kg was used in our experiments.68 Therefore, dose de-escalation is planned for further studies. This might also prevent the toxic effects observed in the dogs in this study.

In summary, we demonstrated that the 213Bi–anti-CD45 radioimmunoconjugate can be used to deliver selective radiation to hematopoietic tissue and, in combination with postgrafting immunosuppression therapy using MMF and CSP, allows stable engraftment of DLA-identical marrow grafts. This is the first report of successful marrow allografting after conditioning with radioimmunotherapy alone.

We thank George McDonald, MD, for reviewing the manuscript; Howard Shulman, MD, for performing the pathology studies; Michele Spector, DVM, and the technicians in the canine facilities of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Drs. Nash, Kiem, Zaucha, Georges, Junghanss, and Little, who participated in the weekend treatments; Marie-Terese Little, PhD, Stacy Zellmer, and Serina Gisburne for the DLA typing; the technicians of the hematology and pathology laboratories of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Dr Elizabeth Squires, Sangstat Medical Corporation, Menlo Park, CA, for the gift of oral CSP; Dr Sabine Hadulco, Roche Bioscience, Nutley, NJ, for the gift of MMF; Peter F. Moore, PhD, DVM, for providing the CA17.6B3 antibody; and MDS Nordion, Vancouver, British Columbia, for the gift of 123I.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 17, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0322.

Supported by a grant from the Gabrielle Rich Leukemia Foundation and in part by grants HL36444, CA78902, and CA15704 from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD. W.A.B. was supported by a fellowship from Deutsche Krebshilfe, Dr Mildred-Scheel-Stiftung für Krebsforschung.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Brenda M. Sandmaier, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave North, D1-100, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109-1024; e-mail: bsandmai@fhcrc.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal