Key Points

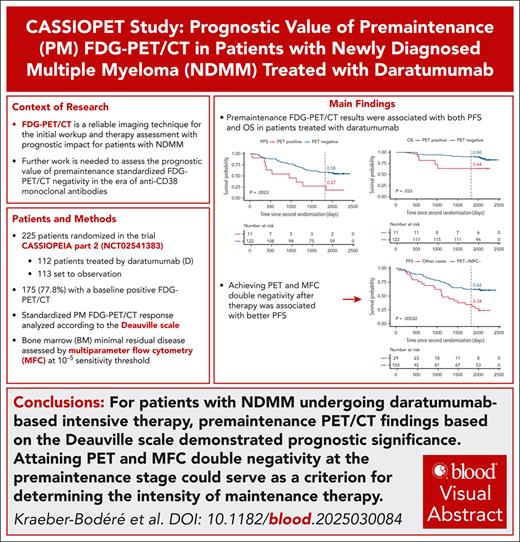

PM PET showed prognostic impact in daratumumab-treated patients.

Better PFS was shown for patients who were both PET- and MFC-negative.

Visual Abstract

The CASSIOPEIA trial demonstrated superior progression-free survival (PFS) with the addition of daratumumab to bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (D-VTd) induction/consolidation, and with daratumumab maintenance vs observation in transplant-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM). The companion study, CASSIOPET, assessed the prognostic value of premaintenance (PM) positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) response, based on the standardized Deauville score on PFS and overall survival (OS), in addition to bone marrow (BM) minimal residual disease (MRD) detection by multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) at 10–5 level. PM PET/CT was available for 225 patients: 112 patients treated with daratumumab after D-VTd (59) or bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTd; 53), and 113 patients followed by observation after D-VTd (56) or VTd (57). At PM, 92% of the 175 baseline PET-positive patients achieved PET negativity, with a longer PFS in univariate analysis (P = .019) and a major trend of prolonged OS (P = .056). In univariate analysis, patients who achieved both PET and MFC negativity were found to have a better PFS (P < .0001) than those who had at least 1 positive result. In daratumumab-treated patients, PM PET negativity was associated with prolonged PFS and OS in univariate analysis (P = .0023 and P = .033, respectively), and double MFC and PET negativity was independently associated with PFS by multivariate analysis (P = .0006). This study confirms the prognostic relevance of a PM PET response in patients with NDMM treated with daratumumab in addition to MRD detection by MFC at the BM level. This trial was registered at ww.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02541383.

Medscape Continuing Medical Education online

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology. Medscape, LLC is jointly accredited with commendation by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Successful completion of this CME activity, which includes participation in the evaluation component, enables the participant to earn up to 1.0 MOC points in the American Board of Internal Medicine's (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. Participants will earn MOC points equivalent to the amount of CME credits claimed for the activity. It is the CME activity provider's responsibility to submit participant completion information to ACCME for the purpose of granting ABIM MOC credit.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at https://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print the certificate. For CME questions, see page 3130.

Disclosures

CME questions author Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC, declares no competing financial interests.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will:

Describe the prognostic implications of premaintenance (PM) positron emission tomography (PET) among daratumumab-treated patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM), based on the final analysis of the CASSIOPET study

Describe the prognostic implications of PET and multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) negativity among all patients with NDMM, based on the final analysis of the CASSIOPET study

Describe the clinical implications of PET and MFC findings in patients with NDMM, based on the final analysis of the CASSIOPET study

Release date: December 18, 2025; Expiration date: December 18, 2026

Introduction

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) is a reliable imaging technique at initial workup and for response to therapy assessment of patients with symptomatic multiple myeloma (MM), with a major prognostic impact on progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) at each time point.1-6 PET/CT-positive features at diagnosis have been found to correlate with poorer outcomes, as well as PET/CT positivity before autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), after transplantation, and before maintenance.3-6 The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine Focus 4 expert consensus recommendations recommend 18F-FDG PET/CT as the gold-standard imaging technique to assess response to therapy in MM,7,8 and a PET/CT standardization based on the Deauville score (DS) for complete metabolic response (CMR) has been proposed.9 In addition, functional diffusion-weighted (DW)–magnetic resonance imaging with the calculation of the apparent diffusion coefficient value, even if not yet mentioned in the imaging guidelines, allows response to therapy assessment in MM as well, and the Myeloma Response Assessment and Diagnosis System criteria have been suggested for standardization of interpretation.10

Due to the impressive efficacy and deeper responses of new therapeutic strategies in transplant-eligible patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM), the IMWG consensus refined the response criteria, including the assessment of bone marrow (BM) minimal residual disease (MRD) using next-generation multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) or next-generation sequencing with sensitivities of 10–5 and 10–6. Although BM MRD negativity is associated with improved outcomes,11-14 relapse still occurs in patients who were negative, possibly due to the presence of extramedullary disease (EMD), residual medullary disease (eg, bone focal lesion [FL]) outside the site of BM sampling, or patchy BM involvement.15,16 The IMAJEM study showed that patients with BM MFC at 10–4 and PET/CT double negativity before maintenance achieved prolonged PFS compared to patients who were not double negative.5 This was confirmed in the more recent FORTE imaging substudy using standardized PET/CT CMR and BM MFC at 10–5.6 However, further work is needed, as no previous studies have reported on the usefulness of PET/CT and the validity of the CMR definition in the era of anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies, which are currently the standard of care.

The phase 3 CASSIOPEIA trial investigated the efficacy of daratumumab, a CD38-targeting monoclonal antibody, plus bortezomib/thalidomide/dexamethasone (D-VTd) vs bortezomib/thalidomide/dexamethasone (VTd) in transplant-eligible patients with NDMM.17-19 In CASSIOPEIA part 1, patients were randomized to receive 4 induction cycles, underwent ASCT, and 2 consolidation cycles of D-VTd or VTd. In part 2, patients who achieved a partial response (PR) or better after consolidation underwent a second randomization to observation-only or maintenance therapy with daratumumab monotherapy. Long-term follow-up results of CASSIOPEIA showed that daratumumab-based induction/consolidation followed by daratumumab maintenance resulted in the deepest and most durable MRD negativity, leading to superior PFS outcomes, confirming D-VTd induction and consolidation as the standard of care, and supporting the option of subsequent daratumumab monotherapy maintenance for transplant-eligible patients with NDMM.18,19

The first analysis (after part 1) of CASSIOPET, a companion study of CASSIOPEIA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02541383), reported after a median follow-up of 29.2 months in a subset of patients with baseline characteristics similar to the overall CASSIOPEIA population, confirmed the prognostic value of baseline PET/CT for PFS.20 Here, we report the final analysis of the CASSIOPET study, which assessed the prognostic value of premaintenance (PM) standardized PET/CT response based on DS in combination with BM MFC negativity at 10–5 threshold taken at the same time period.

Methods

Patients

The study design and eligibility criteria for the CASSIOPEIA trial have been previously published.17,18 Briefly, eligible patients were aged between 18 and 65 years, with NDMM, eligible for high-dose chemotherapy with ASCT, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 to 2, and adequate BM and organ function. In part 1, patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 4 cycles of 28-day pretransplant induction therapy and 2 cycles of 28-day posttransplant consolidation treatment with D-VTd or VTd. After induction, patients received cyclophosphamide and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to mobilize stem cells, followed by conditioning with melphalan and ASCT. The primary end point, stringent complete response, was evaluated 100 days after ASCT. In CASSIOPEIA part 2, patients achieving a PR or better 100 days after ASCT underwent a second 1:1 randomization to observation or maintenance therapy with IV daratumumab 16 mg/kg every 8 weeks, followed by observation until disease progression or for up to 2 years.

Among the patients randomized in CASSIOPEIA, patients were eligible for inclusion in CASSIOPET20 if they had undergone a PET/CT scan within 6 weeks before the first randomization in CASSIOPEIA. Patients were excluded if they were physically unable to access a PET/CT scanner or remain motionless for the duration of the scan, had uncontrolled diabetes, or had received steroids within 12 hours before the PET/CT scan. All patients provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by a local independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each study site.

PET/CT assessment

PET/CT scans were performed at baseline (before first dose) and PM (day 100 [±7 days] after ASCT) at each hospital. All patients fasted for ≥6 hours before the PET/CT scan. Dexamethasone was not to be administered within 12 hours before the PET/CT scan. Blood glucose levels were measured before 18F-FDG injection with a preferred glycemia level of ≤150 mg/dL, but up to 200 mg/dL was allowed. No insulin was administered within 2 hours before 18F-FDG injection, and no oral contrast medium was given. Patients could receive a mild oral sedative before the 18F-FDG injection if required. Whole-body imaging (from the top of the head to the feet, with arms along the body) was performed 55 to 75 minutes after the 18F-FDG injection. First, scout and low-dose CT data (head to feet) were acquired, followed by PET data acquisition, image reconstruction, and analysis.

The acquired imaging data were uploaded to a central electronic repository system (Keosys, Saint-Herblain, France) and analyzed using the Imagys platform. In accordance with the Italian Myeloma criteria for PET Use study criteria and previously published guidelines,1,2,9,21 a 5-point DS (range, 1-5) was used and applied to BM, bone FLs, EMD, and paramedullary disease (PMD). PET images were interpreted by an independent team of nuclear medicine physicians with extensive experience in MM and who were blinded to the randomization arm. CT acquisition was heterogeneous between centers, and the CT analysis was not an objective of this trial. The interpretation of the PET/CT scans did not include a separate evaluation of the CT scan; therefore, patients could have been PET negative but still have lytic lesions on the CT scan.

MRD assessment

Definition of response and relapse

CMR rate was defined as uptake less than or equal to the mediastinal blood pool in all baseline localizations, including diffuse BM, FLs, EMD, and PMD (DS1 or 2). Unconfirmed CMR (uCMR) was defined as uptake between the mediastinal blood pool and the liver background (DS3). Partial metabolic response (PMR) was defined as a decrease in the number and/or activity of diffuse BM, FLs, EMD, or PMD, but persistence of lesions or diffuse BM uptake above liver activity (DS4 or 5). Patients with stable disease had no significant change in FLs, EMD, or PMD from baseline. PET-positive patients were defined as those with PMR and stable disease, and PET-negative patients as those with CMR and uCMR.

End points and statistical analysis

The primary end point of the CASSIOPET study was PFS from the second randomization, defined as the time from PET/CT and MFC-MRD assessment 100 days after ASCT (after ASCT and consolidation therapy), and either confirmed as progressive disease according to IMWG criteria or death, in patients achieving both MFC-based MRD and PET/CT negativity vs patients not achieving double negativity. Secondary end points were: OS from second randomization defined as the time from PET/CT and MFC-MRD assessment 100 days after ASCT, and death in the overall population; PFS and OS in the subgroup of patients treated with daratumumab in induction, consolidation, or maintenance phase; and PFS and OS of patients achieving CMR compared with those achieving uCMR in the overall population. The Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to describe the distribution of PFS and OS, and PFS and OS comparisons were conducted using a log-rank test. Each variable was analyzed using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis.

The association between PET and MFC MRD was assessed by Fisher exact test and the Cramér ϕ coefficient, and between baseline parameters and PM PET response by Fisher exact test.

The statistical analysis was conducted using R (version 4.1.2).

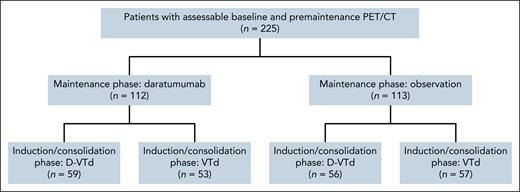

Results

A total of 1085 patients were enrolled in CASSIOPEIA part 1, and 886 patients were randomized in part 2.18 The current analysis of CASSIOPET was performed with a median follow-up of 80.1 months as the final results of CASSIOPEIA.18 Of the 886 patients randomized in CASSIOPEIA part 2, 225 had assessable baseline PET/CT and PM PET/CT (112 patients treated by daratumumab, including 59 after D-VTd and 53 after VTd; and 113 patients set to observation, including 56 after D-VTd and 57 after VTd; Figure 1). At baseline, 50 patients (22.2%) were PET negative, and 175 (77.8%) were PET positive, and were therefore included in the response assessment analysis. None of the 50 baseline PET-negative patients had a positive PM PET (no progressive disease), so response to therapy could not be assessed for these patients. PM MFC was assessable in 223 of the 225 patients, including 174 of the 175 patients with positive baseline PET. Key patient characteristics at study entry and baseline PET/CT results are shown in Table 1.

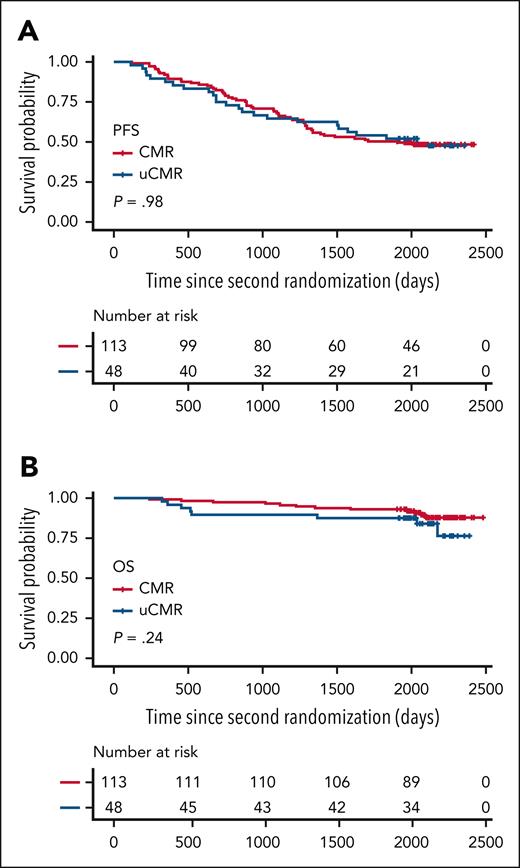

Of the 175 assessable patients with PET positivity at baseline, 113 (64.6%) reached CMR at PM, 48 (27.4%) reached uCMR, and 14 (8.0%) reached PMR (Table 2). Neither cytogenetics (P = .44) nor baseline PET patterns such as EMD or PMD (P = .20) were associated with PM PET response, whereas the presence of >10 FLs was associated with PM PET positivity (P < .01). Overall, 161 (92%) patients were PM PET negative and 14 (8%) PET positive, with a better PFS in univariate analysis for PET-negative vs PET-positive patients (hazard ratio [HR], 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25-0.90; P = .019) and a major trend toward better OS (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.12-1.07; P = .056; Table 3; Figure 2). The probabilities of PFS 5 years after randomization were 29% and 52% for PET-positive and PET-negative patients, respectively, and the probabilities of OS were 71% and 91% for PET-positive and PET-negative patients, respectively. No difference was observed between CMR and uCMR patients on PFS (P = .98) and OS (P = .24; Figure 3).

Survival according to PM PET. PFS (A,C) and OS (B,D) according to PM PET response in the overall population (A-B) and in daratumumab-treated patients (C-D).

Survival according to PM PET. PFS (A,C) and OS (B,D) according to PM PET response in the overall population (A-B) and in daratumumab-treated patients (C-D).

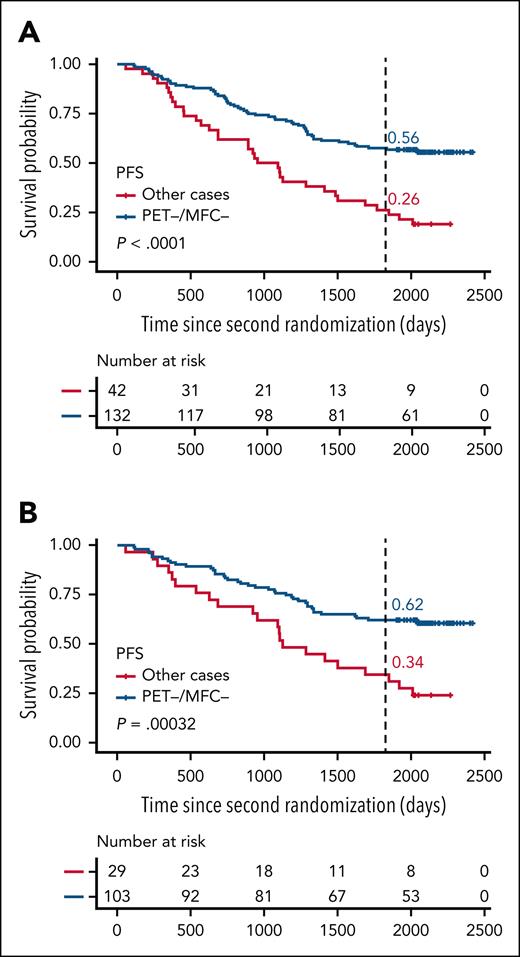

PM MFC was negative in 181 (81.2%) patients and positive in 42 (18.8%) patients, with better PFS in univariate analysis for MFC-negative vs MFC-positive patients (HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.25-0.57; P < .0001; Table 3; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website), but no difference in OS (P = .61; Table 3; supplemental Figure 1). In the subgroup of 174 patients with positive baseline PET, 132 (76.0%) patients were double MFC and PET negative at PM, 8 patients were MFC negative and PET positive (4.6%), 28 patients were MFC-positive and PET-negative (16.1%), and 6 patients were MFC and PET positive (3.4%; Table 2). In univariate analysis, a better PFS was observed for double MFC- and PET-negative patients as compared with others (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.26-0.60; P < .0001; Figure 4; supplemental Figures 2 and 3). Agreement between PM MFC and PET response was weak (0.17).

Survival according to PM PET and MFC. PFS according to PM PET and MFC in the overall population (A) and in daratumumab-treated patients (B): double PET- and MFC-negative patients vs other patients.

Survival according to PM PET and MFC. PFS according to PM PET and MFC in the overall population (A) and in daratumumab-treated patients (B): double PET- and MFC-negative patients vs other patients.

In the subgroup of 46 patients with EMD or PMD at baseline, 37 (80.4%) patients were PM MFC and PET negative (double negative), whereas 4 patients were MFC negative and PET positive (8.7%), 3 patients were MFC positive and PET negative (6.5%), and 2 patients were MFC and PET positive (4.3%). In this subgroup, a trend toward improved PFS was observed for double MFC- and PET-negative patients (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.20-1.14; P = .088), but no difference in PFS was observed between PET-negative and PET-positive patients (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.25-2.09; P = .54). This was also the case when only CMR (and not uCMR) was included in the definition of PET negativity (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.33-1.63; P = .44). However, MFC status (positive vs negative) remained of prognostic relevance in the univariate analysis (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.07-0.58; P = .001).

In the subgroup of 133 patients treated with daratumumab as induction/consolidation and/or maintenance, 122 (91.7%) patients were PM PET negative and 11 (8.3%) were PM PET positive (Table 2), with better PFS and OS in univariate analysis for PM PET-negative vs PM PET-positive patients (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17-0.71; P = .0023; and HR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.11-0.96; P = .033; Table 3; Figure 2). The probabilities of being free from progression 5 years after randomization were 27% and 58% for PET-positive and PET-negative patients, respectively, and the probabilities of OS at 5 years were 64% and 90% for PET-positive and PET-negative patients, respectively. PM MFC was negative in 109 (82.6%) patients and positive in 23 (17.4%) patients, with better PFS in univariate analysis for MFC-negative vs MFC-positive patients (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.23-0.68; P = .0005), but no difference in OS (P = .31; Table 3; supplemental Figure 1). Univariate analysis showed a better PFS for double MFC- and PET-negative patients compared with others in the daratumumab-treated patient group (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.24-0.67; P = .0003; Figure 4; supplemental Figures 2 and 3). In the daratumumab-treated patients, the probabilities of PFS 5 years after randomization were 62% for the double MFC- and PET-negative patients vs 34% for the other patients.

In a Cox multivariable analysis including PM PET negativity, PM MFC negativity, and Revised International Staging System (R-ISS) in the population treated by daratumumab, PM PET negativity was found to be independently associated with longer PFS (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19-0.80; P = .01) and OS (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.09-0.87; P = .027; Table 4). PM MFC negativity was also independently associated with longer PFS (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.22-0.69; P = .001). In a further Cox multivariate analysis considering PM double MFC and PET negativity with R-ISS, only PM double MFC and PET negativity remained independently associated with PFS (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.23-0.67; P = .0006), whereas a R-ISS score of III was associated with a shorter OS (HR, 6.08; 95% CI, 2.10-17.61; P = .0009; Table 5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the prognostic value of PM standardized PET/CT at the era of anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies, which is currently the standard of care in patients with NDMM. The present analysis showed that PM PET negativity based on DS was associated with PFS and OS in univariate analysis, specifically with an independent value on PFS and OS in patients receiving daratumumab in induction, consolidation, or maintenance therapy. Although the prognostic value of PM-positive PET/CT has previously been well established in patients with NDMM,5,6 the prognostic value of positive PM PET/CT in daratumumab-treated patients remained unknown.

Due to the high spatial genomic heterogeneity of MM, detection of MRD both inside and outside the BM is crucial to ensure complete eradication of tumor clones in all compartments, although the prevalence of patients with NDMM with negative BM MRD and positive posttreatment PET is low (5%-7%).2,22,23 In the IMAJEM study, double negativity after consolidation resulted in higher PFS rates at 3 years, and concordance between PET and MFC at the 10–4 threshold was found to be low.5 In the imaging substudy of the FORTE trial, agreement between CMR and MFC negativity at 10–5 was 0.76, and patients who achieved both PET/CT CMR and MFC negativity at PM showed significantly longer PFS compared with the overall population. The present analysis showed a weak agreement and a complementarity between PM PET/CT and MRD assessment by flow cytometry at the 10–5 level in patients receiving new intensive anti-CD38–based therapy, with an independent prognostic value on PFS of the PM double PET and MRD negativity. The complementarity between PET and MFC for the detection of MRD inside and outside the BM after therapy is reinforced in this study by the adverse prognostic impact on OS of PM PET positivity alone (especially in patients treated with daratumumab) and the stronger adverse prognostic impact on PFS of MFC positivity. These results suggest that, even if BM MFC may be affected by disease aggressiveness, MFC analysis of a local BM sample reflects the depth of response. In contrast, PM FDG PET/CT provides a whole-body cartography of tumor viability and metabolism, and thus probably affects OS because it reflects a more aggressive, therapy-resistant plasma cell clone. Finally, the results of this study highlight the crucial importance of achieving PET and MFC double negativity after therapy.

Standardization of criteria for interpretation of FDG PET/CT imaging after therapy is a critical issue. A joint analysis of 2 prospective randomized trials in patients with NDMM showed that the DS of FLs and BM uptake with liver background (DS < 4) as threshold was the best cutoff to define PET negativity.9 The prognostic value of the liver cutoff was confirmed in the present study as well as by the FORTE imaging substudy,6 despite the difference in PET negativity rate between the 2 prospective trials (92% vs 63%), with only patients with PR or better at PM according to IMWG response criteria enrolled in the second randomization of CASSIOPEIA. The high CMR rate observed in this study, compared with previous prospective studies, is probably due to the impressive efficacy of the anti-CD38–based therapy.17,18 We hypothesized in this study that patients achieving only DS of 3 (uCMR) in all pathological medullary and/or extramedullary sites at baseline might have worse PFS or OS compared with patients with “true” CMR (DS1-2) in the era of new very effective targeted therapies, but no difference in PFS and OS was found between CMR and uCMR patients, confirming the validity of the standardization of PET interpretation after therapy,9 and the prognostic relevance of the liver background as a reference (DS < 4) compared with the mediastinal blood pool.

The PM PMR rate was higher in the subgroup with EMD or PMD at baseline compared with the all-positive population (13% vs 8%), but interestingly, unlike MFC, PET negativity was not associated with outcome in this subgroup, whereas double MFC and PET negativity showed a trend toward an improved PFS. This result may be explained by the small number of patients, or by the fact that these patients have a very high-risk profile based on the baseline PET/CT biomarkers.24 Indeed, the first analysis of the CASSIOPET study showed that PMD and EMD were associated with a higher risk of relapse or death.20 Due to the lower sensitivity of PET compared with DW imaging, some patients who were considered PET negative after therapy could have been DW imaging positive, with decreased “cellular” apparent diffusion coefficient values persisting in small areas of residual masses. Moreover, we previously reported in a subgroup of the CASSIOPET population that patients with a high-risk GEP70 molecular signature had more frequent PMD than GEP70-negative patients (P = .003); PMD and IFM15 were independently associated with a lower level of PFS, the presence of both biomarkers defining a group of “double-positive” patients with a very high risk of progression.24 Furthermore, it has been reported that the discrepancy between BM next-generation sequencing or next-generation flow analysis and imaging MRD evaluation was higher in the patients with EMD or bone-related plasmacytomas,25 and that lesion size could be a surrogate marker of spatial genomic heterogeneity and negatively affect the outcome of patients with NDMM, independent of R-ISS, GEP70, and EMD.26

Baseline FDG PET/CT is negative in ∼10% to 20% of patients with symptomatic MM (related to low hexokinase-2 gene expression).20,27,28 The initial analysis of CASSIOPET showed that baseline PET/CT negativity, even if considered as a false negative for disease detection, could be considered for its favorable prognostic value.20 In such patients, FDG PET/CT is not recommended in clinical practice to assess response to therapy.29,30 In baseline FDG-negative patients, other functional imaging methods may be of interest for response assessment, such as C-X-C chemokine receptor 4–targeted PET/CT with [68Ga]Ga-PentixaFor, which has a higher medullary disease detection rate, tumor uptake, and target-to-background ratio than FDG PET/CT31 or DW-magnetic resonance imaging.10 However, prospective studies comparing the performance of these innovative imaging modalities for response assessment with the gold-standard FDG PET/CT are lacking, and their availability remains limited.

In conclusion, PM FDG PET/CT findings based on DS were associated with the outcomes of patients with NDMM in the era of daratumumab-based intensive therapy. Furthermore, PET/CT was complementary to BM MFC assessment at the 10−5 level with an independent prognostic value on PFS and OS. These findings support the integration of both PET/CT and BM MRD assessments into post-consolidation risk stratification, with the achievement of double negativity emerging as a potential criterion to guide maintenance intensity in NDMM.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study, the investigators who participated, staff members at the study sites, staff members who were involved in data collection and analyses, the data safety monitoring committee, and Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and Dutch-Belgian Cooperative Trial Group for Hematology Oncology (HOVON) team.

The CASSIOPET study was funded by the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and Dutch-Belgian Cooperative Trial Group for Hematology Oncology and was supported in part by the French National Research Agency (ANR) “France 2030 investment plan” (references Initiative–Sciences Innovation Territoire Economie Nantes Excellence Trajectory [ANR-16-IDEX-0007] and Laboratoires d'Excellence Development in Hemato-Oncology and Precision Nuclear Medicine) by financial support from the Pays de la Loire Region, and by a grant from Institut National du Cancer–Organisation de la Direction Générale de l’Offre de Soins–INSERM/ITMO Cancer_18011 (Site de Recherche Intégrée sur le Cancer Imaging and Longitudinal Investigations to Ameliorate Decision-Making).

Authorship

Contribution: F.K.-B. and P.M. were responsible for the conception of the work; S.Z., A.P., C.H., D.C., T.F., X.L., K.B., E.I., L.K., C.B., M.-D.L., M.C.M., C.B.-M., B.d.K., J.C., P.S., C.T., and P.M. collected data, and were responsible for the provision of study material or patients; F.K.-B., B.J., and T.C. collected and assembled the data; F.K.-B., B.J., C.T., C.B.-M., C.B., and T.C. analyzed and interpreted the data; T.C. performed the statistical analysis; and all authors wrote and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.Z. served in a consulting or advisory role for Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Janssen, Takeda, Oncopeptides, GSK, and Sanofi and received research funding from Takeda and Janssen (all paid to the institution). A.P. received honoraria from Adaptive, AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, GSK, Janssen, Menarini Stemline, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda. C.H. received honoraria from Celgene, Janssen, Amgen, and AbbVie. D.C. received honoraria from BMS. T.F. received honoraria from, served in a consulting or advisory role for, and served on a speakers’ bureau for Janssen. K.B. served in a consulting or advisory role for and received honoraria from Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, and Takeda. L.K. received honoraria from and served in a consulting or advisory role for Amgen, Janssen, Celgene, and Takeda and had travel, accommodation, or other expenses paid or reimbursed by Amgen and Janssen. M.C.M. received honoraria and research funding from BeiGene and Janssen and served on a speakers bureau for Siemens and Pfizer. M.-D.L. received honoraria from, served in a consulting or advisory role for, and had travel, accommodation, or other expenses paid or reimbursed by Amgen, Janssen, AbbVie, and Celgene. J.C. received honoraria and travel fees from and served in a consulting for Janssen, Sanofi, BMS, Pfizer, and Adaptive and received research support from Sanofi and BMS. P.S. received honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Karyopharm, and Pfizer and received research funding from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, and Karyopharm. P.M. received honoraria from and served in a consulting or advisory role for Janssen. C.T. received honoraria from and served in a consulting or advisory role for Janssen. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Françoise Kraeber-Bodéré, Service de Médecine Nucléaire, University Hospital Hôtel-Dieu, 1 Place Alexis-Ricordeau, 44093 Nantes Cedex 1, France; email: francoise.bodere@chu-nantes.fr.

References

Author notes

Original data are available upon reasonable request from the authors, Thomas Carlier (thomas.carlier@chu-nantes.fr) and Cyrille Touzeau (cyrille.touzeau@chu-nantes.fr).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.