CD20 is a 33-kD B-cell antigen that is expressed from the early pre–B-cell stage of development and is lost on differentiation of B cells into plasma cells. Because CD20 is expressed strictly by B cells, it is an attractive target for B-cell lymphoma therapy. Monoclonal antibodies to CD20 have been used successfully in the treatment of B-cell lymphomas. We hypothesized that a vaccine consisting of CD20 peptide sequences might be capable of inducing an active, specific, humoral immune response to the protein. Vaccine therapy would have the advantage of generating a polyclonal response to the antigen in contrast to the monoclonal response of an infused antibody. Balb/c mice were vaccinated with prototype vaccine constructs that consisted of peptides representing the human or mouse CD20 extracellular sequences conjugated to carrier proteins and mixed with QS21 adjuvant. Sera from the vaccinated mice demonstrated high-titer, specific antibodies to various epitopes on the immunizing peptides in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, weaker antibody binding to native CD20 on cells by flow cytometry, and antibody-mediated complement killing of CD20+ cells in some cases. Specific proliferation and secretion of interleukin 4 and interferon γ by mouse spleen cells in response to the immunizing peptides were also demonstrated. Mice vaccinated with the CD20 peptide keyhole limpet hemocyanin conjugates had a 25% decrease in CD19+ splenic B cells relative to control mice. These data indicate that a biologically active, specific immune response to CD20 can be elicited in mice vaccinated with CD20 peptide conjugates.

Introduction

CD20 is a 33-kD B-cell–specific antigen that is expressed from the early pre–B-cell stage of development and is lost on differentiation into plasma cells.1-3 The precise role of CD20 in B-cell biology is unclear, but CD20 is thought to be involved in B-cell activation and differentiation.4 CD20 has been proposed to have various functions, including mediation of B-cell signaling through kinases,5,6 as well as a role in regulating intracellular calcium.7 CD20 may be a part of protein complexes on the B-cell surface along with major histocompatibility complex II, CD40, and other molecules.8-10 Because CD20 is expressed strictly by B cells but not on early B-cell progenitors or plasma cells, it is an attractive target for the therapy of B-cell lymphoma.11 12

CD20 has a 44–amino acid extracellular domain that is a potential target for immunotherapy. Monoclonal antibodies to CD20 such as rituximab have proven to be an effective immunotherapy for B-cell lymphomas.13 Patients treated with rituximab show decreased peripheral B cells as well as complete tumor regressions in some cases.

Vaccines are an alternative immunotherapeutic approach for the treatment of lymphoma. One vaccination strategy under investigation is the use of the idiotype sequences on the unique immunoglobulin of patient lymphomas as an antigen conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH).14 15 Idiotype vaccination has been successful in mouse models as well as in pilot trials with patients, although it may be limited by the requirement for an individual vaccine for each patient.

Peptide vaccines have been the subject of preclinical and clinical studies for the treatment of various types of tumors, including melanoma, leukemia, and breast cancer.16-21 We hypothesized that a conjugate vaccine containing a peptide representing the CD20 extracellular domain would be capable of inducing an active, specific antibody response to CD20, which might be an alternative to passive infusional therapy. This active therapy might have the advantage of generating a polyclonal antibody response to the antigen in contrast to the monoclonal response of an infused antibody. Such a response might be more effective at recruiting effector responses, as well as less likely to be subject to escape by antigenic alterations.22 23 In addition, such a vaccine might be capable of inducing cellular immunity also, which in combination with the humoral response might more closely mimic the physiologic response mounted against foreign antigens. Further, an active therapy might induce immunologic memory of the antigen, which could reduce the need for, or frequency of, repeated treatments. However, such memory could also prove to be a limitation to such an approach because the target antigen is an autoantigen found on normal B cells, the source of antibody.

To test the hypothesis that peptide vaccination could generate specific responses to native externally exposed portions of the CD20 protein, we vaccinated healthy mice with peptides from the extracellular domain of CD20. We used peptides representing both the mouse and human CD20 sequences to test the possibility that xenogeneic vaccination might be more effective at breaking tolerance than vaccination with the “self” peptide. The peptides were conjugated to the immunogenic carrier protein KLH and other carriers and mixed with immunologic adjuvant to amplify CD4 help and humoral responses to the peptides. We show that it is possible to break tolerance to the CD20 peptide sequences by vaccination with the conjugate vaccine and to produce biologically active immune responses to CD20 in mice as evidenced by demonstration of B-cell depletion and complement cytotoxicity.

Materials and methods

Vaccine preparation

CD20 and P190 control peptides were synthesized and purified to more than 90% purity by Genemed Synthesis (South San Francisco, CA). The sequences were as follows: huCD20 sequence, CKI SHF LKM ESL NFI RAH TPY INI YNC EPA NPS EKN SPS TQY CY; msCD20 sequence, CTL SHF LKM RRL ELI QTS KPY VDI YDC EPS NSS EKN SPS TQY CN. P190 is a peptide representing the product of a chronic leukemia translocation and served as an irrelevant control peptide in these experiments. Each peptide (2 mg) in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide was reduced in 50 mM dithiothreitol at room temperature for 4 hours. Peptides were separated from the dithiothreitol by size exclusion chromatography on a 5-cm P10 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) column. Peptide was detected in the 0.5-mL fractions by spotting samples on a silica TLC plate (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) and spraying with 0.5% ninhydrin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in ethanol. Fractions containing peptide were pooled and added to 1 mg maleimide-activated KLH (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) and allowed to react for 4 hours at room temperature. Unconjugated peptide was separated from the KLH by using a Centricon-50 (Millipore, Bedford, MA), quantitated by measuring the absorbance of the washes at 220 nm in a spectrophotometer, and calibrated by comparison to a peptide standard curve. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) conjugates with peptide were prepared similarly, except that reduced peptides were conjugated to maleimide-activated BSA (Pierce Chemical). Peptide-avidin conjugates were prepared by mixing 1 mg N-terminal biotinylated peptide (Genemed Synthesis) with 1 mg Immunopure Avidin (Pierce Chemical) and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. To verify binding of the peptide to avidin, the conjugate was plated overnight in a 96-well plate, and the lack of binding of biotinylated-alkaline phosphatase was assayed (as described in “Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay”). Purified conjugates were stored in aliquots at −80°C.

Adjuvants

QS21 was supplied by Aquila Pharmaceuticals (Framingham, MA). For each dose, 10 μg of peptide conjugated to KLH and 10 μg QS21 were diluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a final volume of 0.1 mL. Alum was purchased from Pierce Chemical. For vaccinations using alum as an adjuvant, the peptide conjugate was mixed 1:1 (vol:vol) with the alum for 30 to 60 minutes at room temperature before injection. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG; Pasteur Mariaux Connaught Labs, Swiftwater, PA) was obtained from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center hospital pharmacy. For vaccinations using BCG as an adjuvant, 3 × 105 U/dose were added to 10 μg peptide conjugated to KLH. Murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and Flt3 ligand (FL) were gifts from Immunex (Seattle, WA). Vaccinations with conjugates and GM-CSF and FL were done on days 0, 7, and 21, and mice were bled for analysis of serum antibodies on day 28. GM-CSF (10 μg) was injected subcutaneously at the same site on the day before, the day of, and the day after each vaccination with peptide conjugates. For experiments combining FL with GM-CSF, 10 μg FL was injected at the same site on days −6, −4, −2, 0, 2, 4, 19, 21, and 23.

Mice and vaccinations

Healthy female Balb/c mice (7 weeks old; Charles River) were housed in the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center animal facility. Animals were cared for under institutional animal care protocols. The mice were each vaccinated subcutaneously with 10 μg (peptide) conjugated to KLH and mixed with various adjuvants. Except for GM-CSF and FL experiments, vaccinations were done on days 0, 7, 21, and 42, and mice were killed for analyses of serum, spleens, and lymph nodes on day 56.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The 96-well plates (Nunc, Naperville, IL) were coated with 20 ng antigen per well in PBS overnight at 4°C. The wells were blocked with 300 μL 2% BSA in PBS for 1.5 hours at 37°C. The plates were washed 5 times in PBS, and 100 μL mouse serum diluted in 2% BSA/PBS was added to duplicate wells. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 45 minutes and washed; 100 μL of a 1:1000 dilution of goat-antimouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) was added to each well. After washing, 100 μL of 1 mg/mL p-nitrophenylphosphate (Sigma) in diethanolamine/MgCl2 buffer was added per well, and the plates were read at 405 nm in an ELISA plate reader. Duplicate positive control wells of KLH and a standard polyclonal mouse anti-KLH serum were placed on each ELISA plate. ELISA data are expressed as a percentage of this control.

Proliferation assay

Spleens were removed from the mice and made into single cell suspensions by disruption between 2 frosted slides; red blood cells were removed by lysis with ammonium chloride buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA). After washing in RPMI, cells were resuspended in RPMI/5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and counted. Cells (2 × 105) were plated in triplicate in 96-well plates with 10 μg/mL immunizing or control peptides and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4 days. Eighteen hours after adding 0.037 MBq (1 μCi) per well of 3H thymidine (New England Nuclear, Billerica, MA), wells were harvested with a Skatron cell harvester, and samples were analyzed with a beta counter (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Cytokine ELISA

ELISA plates were coated with 100 ng/well rat antimouse interferon γ (IFN-γ; clone R4-6A2; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) or rat antimouse interleukin 4 (IL-4; clone 11B11; Pharmingen) overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed with PBS and blocked with 2%BSA/PBS per well for 2 hours at 37°C. Supernatants from cells cultured for 3 days with peptide as in the proliferation assay were harvested, and 0.1 mL supernatant, media control, or cytokine standards (Pharmingen) were added to the wells in duplicate. Plates were incubated for 18 hours at 4°C and washed; biotinylated rat antimouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2; Pharmingen) or rat antimouse IL-4 (clone BVD6-24G2) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. Signal was detected by addition of extravidin-alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) and p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma) in DEA buffer, followed by reading at 405 nm in an ELISA reader.

Flow cytometry

For analysis of B-cell depletion, cells from individual mouse spleens were blocked in 2% rabbit serum in RPMI on ice and stained with anti–CD19-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti–CD4-FITC, anti–CD8a-phycoerythrin (PE), or the appropriate isotype control (Pharmingen) on ice for 30 minutes. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACScaliber using Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). For CD19+ spleen cell analysis, groups were compared by using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test with Statview 4.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For analysis of mouse serum binding to Raji cells, 0.5 × 106 cells per condition were blocked with 5 μg/mL human intravenous immunoglobulin (Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ) in PBS for 20 minutes, washed, and incubated for 30 minutes on ice with either P190-KLH control mouse serum or huCD20-KLH mouse serum at a 1:10 dilution or 1 μg/tube B1-positive control antibody or IgG2a isotype control (Coulter) in RPMI/10% FBS. The samples were then washed 2 times with 2 mL PBS, followed by incubation with 50 μL of a 1:50 dilution of goat antimouse-FITC antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) for 30 minutes on ice. The cells were then washed 2 times, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde/PBS, and read and analyzed as above.

Complement assay

Ramos and HL60 cells were washed, and 25 μL of 1 × 106 cells/mL were plated per well in RPMI/10% FBS in round-bottom 96-well plates (Corning Costar). Antibody or serum dilution (25 μL) and 25 μL of a 1:5 dilution of baby rabbit complement (Pelfreeze, Brown Deer, WI) were added per well. All conditions were performed in duplicate. Plates were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C, and cells were immediately quantitated for viability by trypan blue exclusion and counting by using a hemacytometer. The experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

Results

Efficient induction of a specific, humoral response to CD20 peptide requires both KLH carrier and QS21 adjuvant

Generation of an immune response to the native CD20 was not straightforward because we expected to have to break tolerance to this widely expressed, cell-surface, protein antigen. A number of steps were taken to overcome this anticipated difficulty. We examined first the need for carrier protein, the requirement for adjuvants, and the role of the peptide sequences in immunogenicity. The CD20 peptide sequence was conjugated to the immunogenic carrier protein, KLH. In addition, peptide conjugates of both mouse and human CD20 peptide sequences were made to compare the efficiency of the xenogeneic sequence with that of the self-peptide in inducing an immune response to the mouse CD20 protein. Several adjuvants were tested.

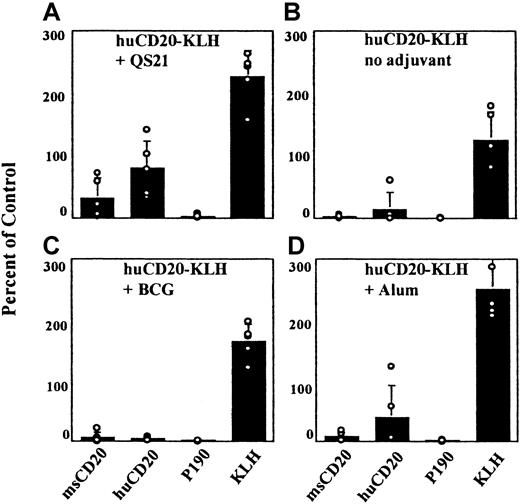

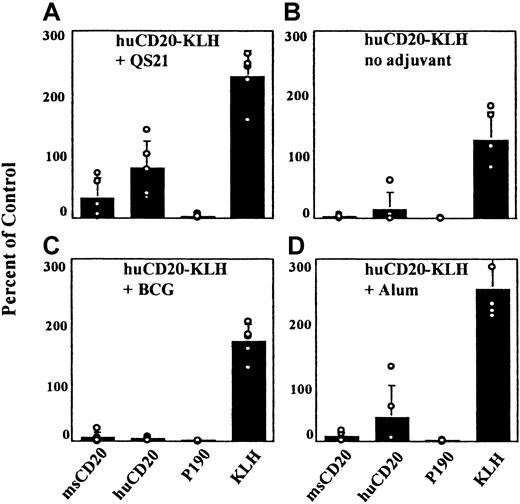

To establish which elements of the conjugate vaccine were important for a humoral response to the CD20 peptides in normal Balb/c mice, we tested the vaccine with and without each individual component. When the huCD20-KLH conjugate was injected without adjuvant, ELISA reactivity with the huCD20 peptide was nearly undetectable (Figure1B). Therefore, it was determined that adjuvant was a necessary component of this vaccine. Different adjuvants were then compared by vaccinating Balb/c mice with the huCD20-KLH conjugate and each adjuvant separately. The use of BCG as an adjuvant gave the lowest titers to the injected peptide (Figure 1C). When alum was used as the adjuvant, more reactivity was detected to the human CD20 peptide than with BCG (Figure 1D). Mice vaccinated with QS21 demonstrated consistently higher titers against the huCD20 peptide than mice vaccinated by using either alum or BCG (Figure 1A). Murine GM-CSF was also tested as an adjuvant with and without FL. Neither condition resulted in detectable titers to the immunizing peptide (data not shown). On the basis of these data, QS21 was chosen as the adjuvant for use in all subsequent experiments.

Serologic responses using different adjuvants.

Mice were vaccinated with the huCD20-KLH conjugate and the different adjuvants noted in the figure. Serum samples from the vaccinated mice were tested in an ELISA against the indicated antigens at a 1:200 dilution as described in “Materials and methods.” Open circles represent value for each individual mouse. Standard deviations of the mean are shown.

Serologic responses using different adjuvants.

Mice were vaccinated with the huCD20-KLH conjugate and the different adjuvants noted in the figure. Serum samples from the vaccinated mice were tested in an ELISA against the indicated antigens at a 1:200 dilution as described in “Materials and methods.” Open circles represent value for each individual mouse. Standard deviations of the mean are shown.

Mice vaccinated with the peptide and QS21 adjuvant, but without carrier, demonstrated minimal ELISA reactivity to both the msCD20 and the huCD20 peptides (Figure 2A), indicating that the carrier protein was also necessary for a strong and specific antibody response to the peptide. Mice vaccinated with the peptides conjugated to BSA rather than to KLH resulted in detectable, modest titers to the immunizing peptides as well. Further experiments in vivo with the BSA constructs, however, failed to show significant biologic effects (such as CD19+ B-cell depletion, data not shown). Therefore, BSA-based constructs were not pursued further.

Serologic response to different peptide conjugates or peptide alone with QS21.

Mice were vaccinated with the indicated conjugates or KLH only. Serum samples from the mice were tested in an ELISA against the indicated antigens at a 1:200 dilution as described in “Materials and methods.” This peptide specificity experiment was repeated 5 times with 5 mice in each group. Open circles represent value for each individual mouse. Standard deviations of the mean are shown.

Serologic response to different peptide conjugates or peptide alone with QS21.

Mice were vaccinated with the indicated conjugates or KLH only. Serum samples from the mice were tested in an ELISA against the indicated antigens at a 1:200 dilution as described in “Materials and methods.” This peptide specificity experiment was repeated 5 times with 5 mice in each group. Open circles represent value for each individual mouse. Standard deviations of the mean are shown.

The specificity of the humoral responses to the immunizing peptides was verified by vaccinating groups of mice with the huCD20-KLH, msCD20-KLH, or P190-KLH (control) peptide conjugates or KLH only with QS21 adjuvant. Sera from the mice demonstrated ELISA reactivity to the corresponding immunizing peptide (Figures 1A and 2B,C); in the case of the huCD20-KLH–vaccinated group there was cross-reactivity with the msCD20 peptide as well (Figure 1A). Control mice vaccinated with KLH only (without any conjugated peptide) in QS21 demonstrated a lack of reactivity to all peptides, as was expected (Figure 2D). Hence, peptide, carrier, and QS21 were all necessary to generate a high-titer, specific immune response to the peptides. The antibodies detected in the ELISA were of both the IgG and IgM subclasses. Without additional vaccination, the mice were capable of yielding high-titer responses in ELISA to 12 weeks.

A more detailed analysis of the antibody response to the mouse and human CD20 peptides in ELISA was done by using peptides representing the N- or C-terminal halves of the immunizing peptides. This analysis was done to determine which portions of the sequences were being recognized by the mouse immune system. The 22–amino acid C-terminal peptide contains 2 cysteine residues, which are expected to form a disulfide loop. Generally, the mice vaccinated with msCD20 peptide made an antibody response against the C-terminal portion of the immunizing peptide, which also recognized the C-terminal portion of the huCD20 peptide. This finding is curious because the antibodies do not recognize the full sequence of huCD20 in ELISA (Table1). The mice vaccinated with the huCD20 construct generated antibodies against the N- and C-terminal halves of human CD20, and, although they do cross-react to recognize the full-length msCD20 peptide, they do not recognize either half separately in ELISA.

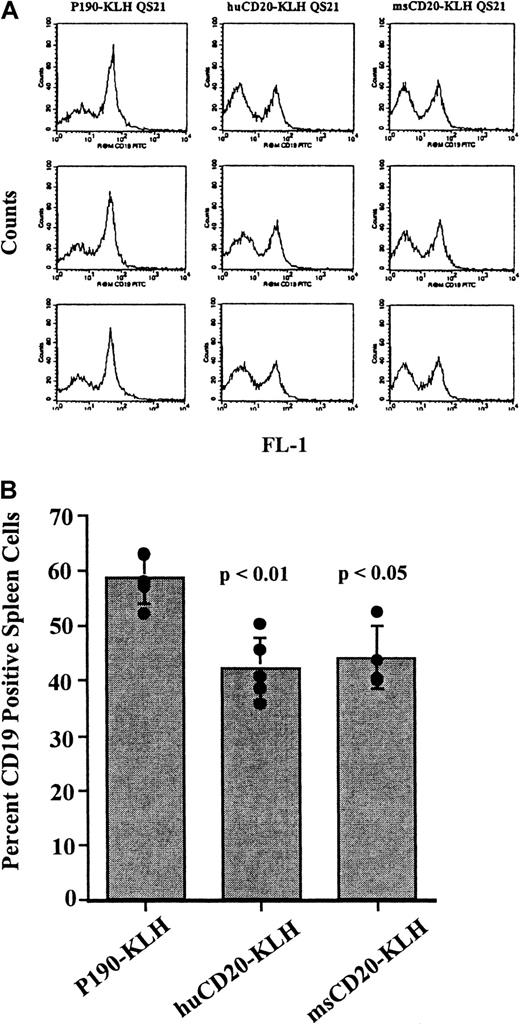

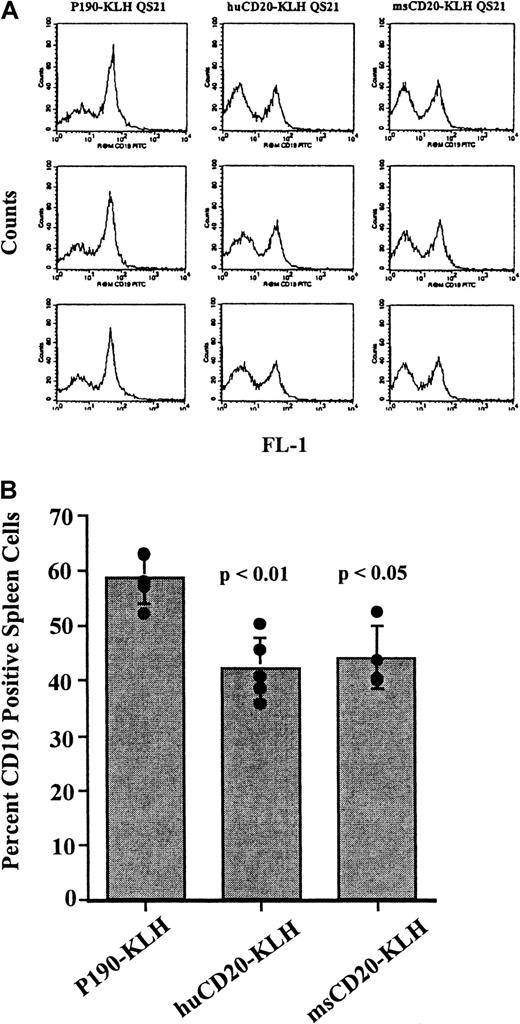

Vaccination of mice with CD20 peptide conjugates causes a decrease in CD19+ spleen cells

Mice were vaccinated 4 times over a 6-week period with huCD20-KLH, msCD20-KLH, or P190-KLH. Spleen cells from the vaccinated mice were stained with anti-CD19 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the effect of the vaccinations on the splenic B-cell population. CD19 was used as the marker for B cells because we were expecting to generate antibodies against CD20 through vaccination. Therefore, detection of B cells by use of an anti-CD20 antibody would have been complicated by competition and blocking by these serum antibodies for binding to the antigen. Spleens from the mice vaccinated with either huCD20-KLH or msCD20-KLH showed a decrease in the proportion of CD19+ cells when compared with those from the P190-KLH vaccine control group (P < .01 for huCD20-KLH,P < .05 for msCD20-KLH) at 8 weeks (Figure3A,B). Absolute numbers of CD19+ spleen cells were also significantly reduced in CD20-vaccinated mice in this experiment (45 × 106 ± 7.4 × 106 for QS21-injected control mice, 38 × 106 ± 13 × 106 for P190-KLH/QS21-injected control mice compared with 8.7 × 106 ± 3.4 × 106 for huCD20-KLH/QS21-injected mice, 14 × 106 ± 3.3 × 106 for msCD20-KLH/QS21-injected mice). Absolute numbers of CD4+and CD8+ T cells did not change significantly, although a general trend in a reduction of CD4+ cells was observed. Therefore, the reduction in the percentage of CD19+ cells appeared to be specific and not related to a corresponding increase in the T-cell population. Small decreases in CD19+ cells were seen in the pooled bone marrow cells of the mice vaccinated with huCD20-KLH compared with controls (data not shown). An additional experiment with a different lot of vaccine showed similar decreases in the proportion of CD19+ spleen cells (30% decrease for huCD20-KLH and 26% decrease for msCD20-KLH compared with P190-KLH-vaccinated controls).

Flow cytometry of CD19+ cells in spleens of vaccinated mice.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of spleen cells from mice vaccinated with huCD20-KLH, msCD20-KLH, or P190-KLH control conjugate stained with rat antimouse CD19-FITC antibody. The X-axis is CD19 fluorescence. The Y-axis is the number of cells. (B) Percentage of CD19+cells in each group of vaccinated mice calculated from the data obtained in A. Bar represents the mean value ± SD. Values from individual mice are represented by circles. P values are for P190-KLH versus huCD20-KLH, and P190-KLH versus msCD20-KLH. This experiment was done twice with similar results.

Flow cytometry of CD19+ cells in spleens of vaccinated mice.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of spleen cells from mice vaccinated with huCD20-KLH, msCD20-KLH, or P190-KLH control conjugate stained with rat antimouse CD19-FITC antibody. The X-axis is CD19 fluorescence. The Y-axis is the number of cells. (B) Percentage of CD19+cells in each group of vaccinated mice calculated from the data obtained in A. Bar represents the mean value ± SD. Values from individual mice are represented by circles. P values are for P190-KLH versus huCD20-KLH, and P190-KLH versus msCD20-KLH. This experiment was done twice with similar results.

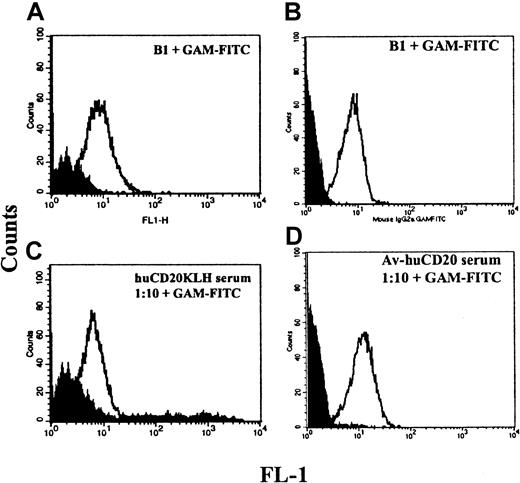

Binding of serum from vaccinated mice to native CD20 protein

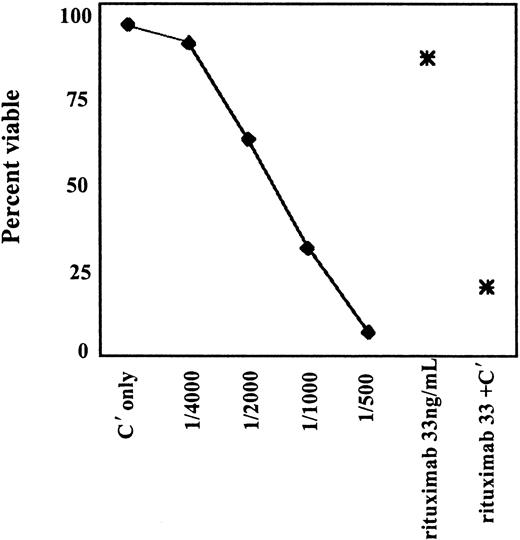

To investigate whether the mechanism of B-cell depletion in the vaccinated mice might be antibody mediated, the ability of the serum antibodies to recognize the native CD20 protein on the surface of the cells was tested by flow cytometry (Figure4). Binding of the serum to Raji, a CD20+ human B-cell lymphoma cell line, was seen in 6 of 10 mice in separate experiments. We hypothesized that one reason for only modest binding to native CD20 on cells with serum from KLH-conjugate vaccinated mice was that there were multiple ways that the peptide might be conjugated to the KLH and that this could result in the production of antibodies largely to a mixture of nonnative structures. To increase the likelihood for recognizing a native CD20 protein, we modified the vaccine to restrict the possible conformations of the peptide. This modification was done by biotinylating the N-terminal amino acid and using avidin as the carrier protein. Sera from 2 of 5 mice vaccinated with this modified vaccine displayed markedly improved binding to CD20+ cells (Figure 4C,D). In addition, these sera were capable of concentration-dependent complement-mediated killing of CD20+ B cells (Figure5). CD20− myeloid cells were not killed (not shown).

Serologic responses of the vaccinated mice to CD20+ cells.

(A) Staining of Raji cells with B1 anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody compared with isotype control (shaded). (B) Binding of mouse serum from a huCD20-KLH–vaccinated mouse compared with serum from a control mouse vaccinated with P190-KLH (shaded). Both sera were diluted 1:10. (C) Binding of B1 compared with isotype control. (D) Binding of serum from a mouse vaccinated with huCD20-avidin at 1:10 dilution and from a mouse vaccinated with avidin only (shaded).

Serologic responses of the vaccinated mice to CD20+ cells.

(A) Staining of Raji cells with B1 anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody compared with isotype control (shaded). (B) Binding of mouse serum from a huCD20-KLH–vaccinated mouse compared with serum from a control mouse vaccinated with P190-KLH (shaded). Both sera were diluted 1:10. (C) Binding of B1 compared with isotype control. (D) Binding of serum from a mouse vaccinated with huCD20-avidin at 1:10 dilution and from a mouse vaccinated with avidin only (shaded).

Complement-mediated killing of Ramos cells with serum from a mouse vaccinated with huCD20-avidin conjugate.

Serum plus complement was serially diluted as shown along the X-axis. Rituximab with complement (C′) was used as a positive control at 33 ng/mL, and rituximab or C′ alone was used as a negative control.

Complement-mediated killing of Ramos cells with serum from a mouse vaccinated with huCD20-avidin conjugate.

Serum plus complement was serially diluted as shown along the X-axis. Rituximab with complement (C′) was used as a positive control at 33 ng/mL, and rituximab or C′ alone was used as a negative control.

To investigate whether vaccination with the CD20 peptides might induce antibodies that recognize the same epitope as rituximab, we tested the ability of the CD20 peptides to be recognized by rituximab in an ELISA. CD20 peptides alone and N-terminal–biotinylated CD20 peptides bound to avidin were assayed in an indirect ELISA. Rituximab demonstrated binding to the huCD20 peptide with its orientation restricted on avidin and showed 5-fold less binding to msCD20-avidin and to the peptides alone. No binding of an irrelevant, humanized antibody was seen to either peptide, and rituximab did not bind to the P190 control peptide. Binding was peptide-concentration dependent and antibody-concentration dependent. These data indicate that this peptide might exist in various conformations, only a portion of which represent the epitope recognized by rituximab and that the huCD20 peptide with a restricted conformation better mimics the actual conformation of CD20 on the cell surface than a peptide with random conformations.

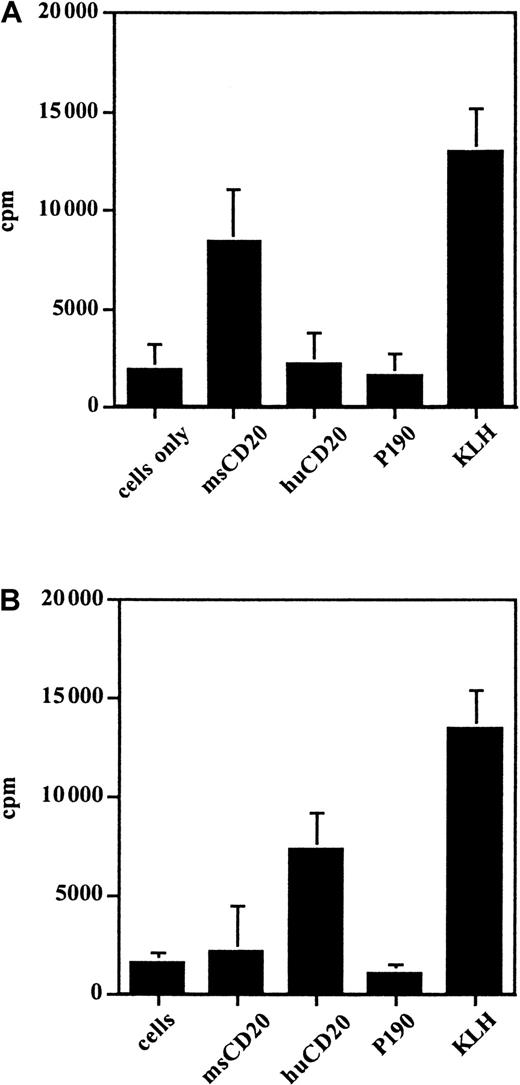

Proliferation of lymphocytes in response to the immunizing peptides

Lymphocytes from the spleens of the vaccinated mice were tested for proliferation in the presence of the CD20 peptides to determine if a T-cell response could be elicited and as a demonstration of the specificity of the cellular immune response for CD20. Lymphocytes from mice vaccinated with msCD20-KLH proliferated in the presence of msCD20 peptide and KLH but not in the presence of the control peptides. Lymphocytes from mice vaccinated with huCD20-KLH proliferated in the presence of huCD20 peptide and KLH (Figure6). In both cases the response to the immunogenic carrier protein KLH was higher than the response to the peptides, as expected. Lymphocytes from the vaccinated mice were also tested for specific secretion of IFN-γ and IL-4 by cytokine ELISA in response to the immunizing peptides. This test further demonstrated the specificity of the T-cell immune response to CD20 and confirmed that the cells involved in the proliferation were T cells. Production of both IFN-γ (1500-2000 pg/mL) and IL-4 (20-100 pg/mL) was seen in response to the respective immunizing peptides and KLH but not with P190 control peptide.

Proliferation of spleen cells from vaccinated mice in response to various antigens, including those as measured by incorporation of 3H-thymidine.

Splenocytes were from mice vaccinated with (A) msCD20-KLH and (B) huCD20-KLH. This experiment was done twice with similar results.

Proliferation of spleen cells from vaccinated mice in response to various antigens, including those as measured by incorporation of 3H-thymidine.

Splenocytes were from mice vaccinated with (A) msCD20-KLH and (B) huCD20-KLH. This experiment was done twice with similar results.

Discussion

Passive infusion of antibodies to CD20 has been shown to be therapeutically effective in patients with CD20+ B-cell malignancies. Our goal was to demonstrate that effective vaccination against CD20 peptides was possible and could result in an active, specific immune response to the CD20 molecule, a widely expressed self-antigen. We demonstrated that mice vaccinated with either the mouse or human CD20 peptides mounted antibody responses and T-cell proliferative and cytokine responses to the peptides. The antibodies detected were both IgG and IgM, indicating isotype switching and further suggesting the involvement of T-cell help in the immune response. Carrier protein and QS-21 adjuvant were each individually defined as important for a high-titer humoral immune response to the peptides. Finally, biologic activity was demonstrated by showing complement-mediated killing of B cells and that the proportion of splenic B cells decreased in mice vaccinated with CD20 peptide.

Alum, BCG, GM-CSF, and QS21 were tested as adjuvants initially because they are widely used in humans, and one goal ultimately was to prepare a vaccine suitable for human use. In this system, QS-21 gave the best antibody response to the peptides, with alum and BCG giving inferior responses. This finding is consistent with results previously published.24,25 The requirement for the peptide to be conjugated to an immunogenic carrier protein such as KLH was also demonstrated, and this requirement has also been seen in other vaccine systems.26 27

We designed the prototype vaccine based on the idea that 2 conserved cysteine residues were likely to dimerize to form an extracellular loop in the native CD20 molecule. We used a 44–amino acid peptide antigen that represented the entire extracellular region of CD20, which contains these cysteines. It was anticipated that the presence of the cysteine loop would restrict the conformation of the peptide and that the resulting peptide structure would encourage the production of antibodies that could recognize the native CD20 protein. This proved to be more difficult than anticipated. Mice vaccinated with the msCD20-KLH conjugate demonstrated a strong and specific antibody response to the msCD20 peptide. Mice vaccinated with the huCD20-KLH showed responses that not only recognized huCD20 peptide but also cross-reacted with the msCD20 peptide in the ELISA. Despite significant antibody titers to the peptides in ELISA, serum reactivity with the native protein on the cell surface as measured by flow cytometry was only modest and was not demonstrated with sera from all mice.

There are several explanations for the lack of a robust response to the cell surface protein. It is possible that the lack of strong binding to cells is due to the absorption of the antibodies that recognize native CD20 out of the serum by the normal CD20+ B cells in the circulation. If this is true, the antibodies that are detected in ELISA could be the low-affinity antibodies or antibodies remaining that were not capable of recognizing the 3-dimensional CD20 structure but are only capable of recognizing linear amino acid epitopes on the peptides in the ELISA plate. To address this possibility it would be interesting to vaccinate CD20 knockout mice with the peptide conjugates to determine if antibodies that recognize native CD20 are more abundant in the serum. Alternatively, CD20 may form multimers at the cell surface8 or undergo other tertiary changes that could alter the conformation of the extracellular region. It is also possible that the extracellular peptide sequences alone, despite the presence of the disulfide loop, do not provide an adequate 3-dimensional representation of the native CD20 as it exists in situ on the cell. Therefore, most of the easily detected humoral response may simply not be directed to the native protein. In addition, the epitopes on the native CD20, a widely expressed self-antigen, are likely to be strongly tolerizing in the animals, so that generating a response is difficult.

To investigate the possibility that the modest binding to native CD20 was due to the multiple nonnative conformations of peptide in the KLH-peptide vaccine and that this resulted in a very heterogeneous antiserum, we made a vaccine of biotinylated peptide with avidin as a carrier protein. In this case the peptide could only bind one way to the carrier protein with the cysteine loop directed outward, thus restricting the possible orientations of the peptide on the carrier. Mice that were vaccinated with this peptide-avidin vaccine generated antibodies that better recognized the CD20+ cells. Additionally, these sera were capable of mediating efficient complement killing of CD20+. This result gave support to our hypothesis that we could increase the humoral response directed to the native CD20 extracellular loop structure by restricting the orientation or conformation of the peptide. This finding also supports our explanation that the modest binding of serum from the KLH-conjugate mice was due in part to vaccination with a large mixture of peptide conformations.

Lymphocytes from mice vaccinated with msCD20-KLH proliferated in response to the msCD20 but not the huCD20 peptide. The lymphocytes from the mice vaccinated with the huCD20-KLH conjugate demonstrated proliferation in the presence of huCD20. Lymphocytes also demonstrated specific release of the helper T-cell cytokines IL-4 and IFN-γ in the presence of immunizing peptides. These data further support the involvement of T cells in the immune response to CD20 peptides. Moreover, the presence of T-cell help correlates with the IgG responses seen.

In mice vaccinated with the CD20 peptides conjugated to KLH, normal B cells were depleted by 25% compared with control mice. Detection of this decrease in the B cells is surprising, as one would anticipate that a healthy mouse would be able to constantly replace lost B cells and conceal any effect of the vaccination. Similarly, in preclinical trials of rituximab in monkeys, only partial depletion of B cells in the lymph nodes was seen.12

One concern with vaccinating against a normal B-cell antigen such as CD20 is that vaccination could result in prolonged autoimmunity to B cells. It is possible that successful immunization could lead to a brief or chronic CD20+ B-cell deficiency. The effect of such a B-cell depletion, however, is difficult to predict. Patients treated with rituximab (anti-CD20) who show prolonged B-cell depletion have not been shown to have significantly compromised immunity during the treatment period in which their normal B-cell levels are decreased.13,28 It is also unlikely that a significant anti-CD20 immune response could be sustained without constant re-immunization. Vaccine studies by other groups using KLH conjugate vaccines and QS-2129,30 have shown that antibodies resulting from vaccination can eventually drop to undetectable levels without repeated booster injections. We observed this as well (not shown). Although cells that express CD20 were depleted in our experiments, mice lacking the CD20 protein altogether have been generated, and these mice were found to be phenotypically normal and capable of producing immune responses.31 Also, the B-cell population would not necessarily be permanently depleted of CD20+ B cells even if a successful immunization occurred. If antibodies are an important mechanism of elimination of the B cells, depletion of CD20+ B cells might ultimately cause a decrease in the immune response to CD20 once the antibody-secreting CD20− plasma cells has dropped because of normal cell turnover. Taken together, these observations suggest that the temporary loss of CD20+ cells because of vaccination might not be associated with significant morbidity.

It is also possible that CD4+ T cells could be effectors of the anti-CD20+ B-cell response.32 This hypothesis is reasonable because lymphocyte proliferation and secretion of IL-4 and IFN-γ in response to the immunizing peptides were demonstrated. CD4 cells could also contribute to the anti-CD20 antibody response and possibly to an anti-CD20 CD8+ T-cell response. CD8-mediated cytotoxicity was not demonstrated by chromium-51 release assay, but, given the general insensitivity of this assay when using weakly immunogenic peptides without in vitro stimulation and expansion of CD8 cells, it is possible that a CD8 response was generated but not detected. CD4 T cells have been shown to mediate activation of cytotoxic macrophages, eosinophils, and natural killer cells in mouse models32,33 and have been shown to be important in the effector phase of tumor rejection in various mouse tumor models.34 35

It is intriguing that this vaccination approach against CD20 peptides was able to break tolerance and yield a strong humoral and proliferative response to the CD20 peptides and produce modest depletion of normal B cells in mice. Future work will better define the mechanisms of CD20+ B-cell elimination, the long-term effect of immunization against this self-antigen, and possible therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of murine B-cell lymphoma.

We thank Lawrence Lai, Tatiana Koronsvit, William Fox, and Sirpa Salo-Kostmayer for technical assistance.

Supported by grants RO1CA55349 and P01CA23766 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the Society of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and the Lymphoma Foundation. D.A.S. is a Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Science Professor.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

David A. Scheinberg, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10021.