Abstract

Chemokines are mediators in inflammatory and autoimmune disorders. Aminoterminal truncation of chemokines results in altered specific activities and receptor recognition patterns. Truncated forms of the CXC chemokine interleukin (IL)-8 are more active than full-length IL-8 (1-77), provided the Glu-Leu-Arg (ELR) motif remains intact. Here, a positive feedback loop is demonstrated between gelatinase B, a major secreted matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9) from neutrophils, and IL-8, the prototype chemokine active on neutrophils. Natural human neutrophil progelatinase B was purified to homogeneity and activated by stromelysin-1. Gelatinase B truncated IL-8(1-77) into IL-8(7-77), resulting in a 10- to 27-fold higher potency in neutrophil activation, as measured by the increase in intracellular Ca++concentration, secretion of gelatinase B, and neutrophil chemotaxis. This potentiation correlated with enhanced binding to neutrophils and increased signaling through CXC chemokine receptor-1 (CXCR1), but it was significantly less pronounced on a CXCR2-expressing cell line. Three other CXC chemokines—connective tissue-activating peptide-III (CTAP-III), platelet factor-4 (PF-4), and GRO-α—were degraded by gelatinase B. In contrast, the CC chemokines RANTES and monocyte chemotactic protein-2 (MCP-2) were not digested by this enzyme. The observation of differing effects of neutrophil gelatinase B on the proteolysis of IL-8 versus other CXC chemokines and on CXC receptor usage by processed IL-8 yielded insights into the relative activities of chemokines. This led to a better understanding of regulator (IL-8) and effector molecules (gelatinase B) of neutrophils and of mechanisms underlying leukocytosis, shock syndromes, and stem cell mobilization by IL-8.

Introduction

Gelatinase B, or MMP-9, belongs to the growing family of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). It is produced mainly by neutrophils but is also produced by various other blood-derived cell types—for example, monocytes, macrophages, eosinophils, and leukemic cells.1,2 Its production has been associated with various physiological and pathologic phenomena, such as leukocyte migration,3 bone resorption,4,5 cancer cell metastasis,6,7 and autoimmune disease.8Physiological production and function and pathologic activities of MMP, including gelatinase B, are regulated at several levels.9The best-known function for MMP is the degradation of extracellular matrix components. However, other substrates are also degraded by MMP.10 The definition of the substrates for different gelatinases has been hampered by the lack of selective production and isolation procedures to obtain pure proteases. This was circumvented here by using neutrophils as the source for gelatinase B. In contrast to other cell types, the latter do not produce gelatinase A or complexes of gelatinase B with tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP).11

Chemokines are low-molecular-mass proteins that exert potent chemoattractant activities on leukocytes and that have effects on angiogenesis and hematopoiesis. Based on the position of the 4 conserved cysteine residues, chemokines have been grouped into 2 major families. CXC chemokines with one residue between the first 2 cysteines are active on neutrophils, lymphocytes, or both. CC chemokines with 2 adjacent cysteines are active on a variety of cell types, including monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, and lymphocytes.12 13

Human interleukin-8 (IL-8) was identified as a potent neutrophil chemoattractant and a granulocytosis-promoting protein,14and it became one of the best-characterized CXC chemokines. In front of the first cysteine residue, IL-8 contains the Glu-Leu-Arg (ELR, amino-acid sequence in 1-letter code) motif, essential for its neutrophil chemotactic activity. Besides the chemoattractant activity on neutrophils, IL-8 triggers neutrophils to release the content of some of their granules.1

Different aminoterminal variants of natural IL-8 have been identified. For instance, IL-8(1-77) (AVLPRSAKELRCQC…), and IL-8(6-77) (SAKELRCQC…) were characterized as the major forms derived from endothelial cells or fibroblasts and leukocytes, respectively. Additional natural forms are IL-8(-2-77) (EGAVLPR…), IL-8(7-77), IL-8(8-77), and IL-8(9-77).15 In general, the shorter forms of IL-8 are more active than the full-length form.

Other members of the CXC chemokine family, containing the ELR-motif, are granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 (GCP-2), epithelial-cell–derived neutrophil attractant-78 (ENA-78), GRO-α, GRO-β, GRO-γ, and connective tissue-activating peptide-III (CTAP-III). CTAP-III is a chemotactically inactive, aminoterminally processed form of platelet basic protein. Further processing of CTAP-III by monocyte or neutrophil proteases yields the chemotactic neutrophil-activating peptide-2 (NAP-2).16,17 Processing of intact ENA-78 by cathepsin-G yields the most potent aminoterminal variant [ENA-78(9-78)] of this neutrophil chemotactic protein.18,19 Truncated natural variants of GRO-α and GRO-γ were found to be more active than their respective full-length forms, whereas limited aminoterminal processing of human GCP-2 does not affect its biologic activity.18Platelet factor-4 (PF-4) is a CXC chemokine without the ELR-motif and without clear chemoattractant activity. However, the latter has been shown to promote degranulation by neutrophils after pretreatment with tumor necrosis factor-α20 and to play a role in the regulation of angiogenesis.21

By analogy with IL-8, different natural truncation variants of CC chemokines have been isolated. A monocyte chemotactic protein-2 (MCP-2) form, which lacks 6 aminoterminal residues, was identified as a chemokine inhibitor.22 RANTES processed by dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26 lacks 2 aminoterminal residues and is a chemokine inhibitor with potent antihuman immunodeficiency virus activity.23 We here describe the processing of several chemokines by the secreted metalloproteinase gelatinase B, in contrast to the proteolytic processing by the membrane-anchored serine protease CD26.

Materials and methods

Purification of natural gelatinase B from human neutrophils to homogeneity

Natural gelatinase B was isolated from human neutrophils by a method modified from that of Masure et al.1 Human neutrophils were isolated from buffy coats (Red Cross, Antwerp, Belgium).18 After 20 minutes of preincubation with 3 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) at 37°C, 0.5 μmol/L fMLP and 3 mmol/L PMSF were added to stimulate degranulation during the next 20 minutes. The cell supernatants were harvested, filtered, loaded on a gelatin–Sepharose substrate affinity column (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), and eluted as described.1 The eluate was subsequently dialyzed against assay buffer (100 mmol/L Tris- HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.01% Tween 20). In the next step, the covalent heterodimeric complex of gelatinase B with neutrophil gelatinase B–associated lipocalin (NGAL) was removed by affinity chromatography on a monoclonal antibody directed against NGAL (courtesy of Dr T. Bratt and Dr N. Borregaard).24 The purity of gelatinase B was controlled by reducing and nonreducing sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie brilliant blue protein staining analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using a commercial Bradford assay (BioRad, Richmond, CA).25

Chemokines and chemokine receptors

To produce significant amounts of natural chemokines, human monocytes or mononuclear cells were purified from buffy coats and stimulated with bacterial lipopolysaccharide (2 μg/mL, fromEscherichia coli 0111:B4; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) and concanavalin A (2 μg/mL; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 48 hours at 37°C. Alternatively, purified human platelets were stimulated with thrombin for 24 hours at 37°C for the production of CTAP-III and PF-4.26 The conditioned media were processed through a 4-step purification schedule consisting of concentration on controlled pore glass or silicic acid, heparin or antibody affinity chromatography, cation-exchange chromatography, and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Purity and quantity of natural IL-8 (monocyte-derived), GRO-α (mononuclear cell–derived), CTAP-III, and PF-4 (platelet-derived) were checked by SDS-PAGE, automated Edman degradation on a pulsed liquid phase protein sequencer (477A/120A; PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.26 The Gln46 isoform of human MCP-2 with an aminoterminal pyroglutamic acid was expressed inE coli and purified as described.27 Recombinant human chemokines IL-8(1-77) and RANTES were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells, transfected with CXC chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1) or CXCR2, were kindly supplied by Dr J. M. Wang (National Cancer Institute-Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center, Frederick, MD).28 HEK cells were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 800 μg/mL geneticin.

Activation of gelatinase B by stromelysin-1

Stromelysin-1 (MMP-3; Biogenesis, Poole, UK) was activated with 2 mmol/L 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA) (from a 10× concentrated solution in dimethyl sulfoxide) for 5 hours at 37 °C, according to the instructions of the manufacturer. APMA was removed from the activated enzyme by ultrafiltration on membranes with a 10-kd cutoff (Millipore, Milford, MA) or by dialysis using the Slyde-A-Lyzer units (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Activation of 1 μmol/L gelatinase B was performed with 0.01 μmol/L APMA-activated stromelysin-1 for 4.5 hours in assay buffer at 37°C. The gelatinase B activity was controlled by gelatin zymography and by the conversion of the quenched fluorescent substrate Mca-Pro-Leu-Gly-Leu-Dpa-Ala-Arg-NH2 (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland).29

Digestion of chemokines with purified gelatinase B and detection of cleavage products

Chemokines (4 μmol/L) were incubated with activated neutrophil gelatinase B (0.4 μmol/L) in assay buffer (see above) at 37°C for 20 hours (unless otherwise indicated). Control experiments were conducted under identical conditions without gelatinase B (but with 0.004 μmol/L activated MMP-3). Gelatinase B inhibition experiments were performed at 1.5 μmol/L chemokine and 0.2 to 0.5 μmol/L gelatinase B in the same buffer with the following individual reagents: 15 mmol/L EDTA, 2 mmol/L o-phenantrolin, 0.25 μmol/L recombinant human TIMP-1 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), 2.6 μmol/L gelatinase B–inhibiting monoclonal antibody REGA-3G12,302 mmol/L pefabloc, 2 μg/mL E64, or 67 μg/mL aprotinin (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Chemokine cleavage products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and separated by reverse-phase HPLC on a C8-column using a gradient of CH3CN; absorbance was recorded at 220 nm. Resultant peptides were identified by aminoterminal sequencing and mass spectrometry analysis (see below). Resultant peptide sequences are indicated by one-letter codes, and the number of the first residue—derived from the mature protein—is indicated.

Mass spectrometry analysis of chemokines and chemokine cleavage products

Chemokines and peptides were, if required, first desalted using the C18 ZIPTIP (Millipore) and were subsequently diluted in 50% acetonitrile/50% H2O/0.1% acetic acid. These peptide solutions were analyzed by electrospray mass spectrometry (MS) on an ion trap (Esquire-LC, Brucker, Germany) or on a quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF-2; Micromass, Manchester, UK) apparatus. Sequencing of peptides was performed by tandem MS/MS on the ion trap apparatus. When C18 ZIPTIP was used for desalting chemokines, adducts were observed that were not present in preparations or samples prepared without the use of ZIPTIP; therefore, these adducts were not further considered. In addition, the aminoterminal sequence of specific chemokine peptides was further characterized by Edman degradation as described above.

Competition for 125I–IL-8 binding to CXC receptors

Purified granulocytes, HEK-CXCR1, or HEK-CXCR2 (2 × 106 cells in 200 μL) were incubated with125I–IL-8(6-77) (10 nCi; Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden) and with various concentrations of unlabeled IL-8(1-77) or IL-8(7-77) for 2 hours at 4°C in phosphate-buffered saline with 20 g/L bovine serum albumin. After 3 subsequent washes with 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline and 20 g/L bovine serum albumin, the cell-bound radioactivity was measured with a Triathler γ-counter (PerkinElmer, Norwalk, CT).

Detection of intracellular Ca++ concentrations

Intracellular Ca++ concentrations ([Ca++]i) were measured as described previously.18 Briefly, purified cells (107/mL) were loaded with the fluorescent indicator fura-2 (2.5 μmol/L fura-2/am; Molecular Probes Europe BV, Leiden, The Netherlands) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After 2 washes, cells were stored on ice at 106 cells/mL for a maximum of 1.5 hours. After excitation at 340 and 380 nm, fura-2 fluorescence was detected at 510 nm in an LS50B luminescence spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer) and used for the calculation of the [Ca ++]i.

In inhibition experiments, monoclonal anti-CXCR1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added at a concentration of 15 μg/mL during loading of the cells with fura-2 and during subsequent storage on ice and analysis.

Degranulation

Aliquots of 5 × 106 purified granulocytes, derived from healthy human blood donors, were stimulated in heat-inactivated human plasma with various concentrations of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were removed by centrifugation, and gelatinase B in the supernatant was analyzed by gelatin substrate zymography and subsequently quantified by scanning densitometry.31 Background levels of gelatinase B–zymolysis were subtracted from the zymolysis data obtained after neutrophil stimulation with IL-8(1-77) or IL-8(7-77).

Chemotaxis

Chemotactic activities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were compared in modified Boyden chemotaxis chambers as detailed previously.18 The chemotactic index was defined as the ratio of cells migrated toward the chemokine versus the cell numbers obtained with the excipiens.

Results

Preparation of natural gelatinase B

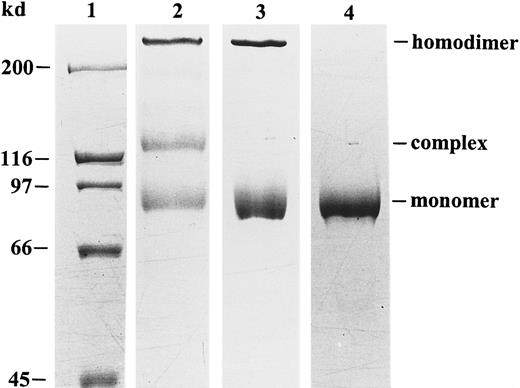

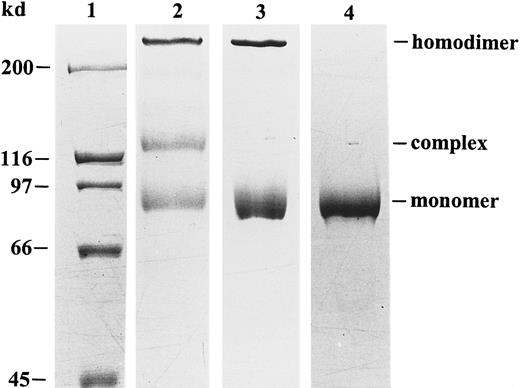

Human peripheral blood neutrophils were used to obtain natural gelatinase B devoid of gelatinase A contamination. Indeed, this cell type does not synthesize gelatinase A or TIMP, and it stores gelatinase B in its proenzyme form in granules. By degranulation, 3 forms of gelatinase B were released into the extracellular space: monomers, disulfide-linked homodimers, and heterodimers with NGAL.32With the use of an NGAL monoclonal antibody, the NGAL complex was removed and an electrophoretically pure preparation of gelatinase B was obtained (Figure 1) and used for all chemokine-processing experiments.

Purification and SDS-PAGE analysis of human neutrophil gelatinase B.

Natural gelatinase B, purified from human neutrophils, occurs in 3 different forms: monomers, disulfide-linked homodimers, and NGAL–gelatinase B complexes.32 Nonreducing SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining before (lane 2) and after (lane 3) removal of the NGAL–gelatinase B complex allows visualization of the positions of the monomers, the dimers, and the NGAL–gelatinase B complexes. After chemical reduction with β-mercaptoethanol, the dimer was dissociated into monomers in the electrophoretically pure preparation (lane 4). Relative molecular masses of the monomer, heterodimer, and homodimer were estimated to be 91, 125 and greater than 200 kd by comparison with the molecular mass markers (lane 1).

Purification and SDS-PAGE analysis of human neutrophil gelatinase B.

Natural gelatinase B, purified from human neutrophils, occurs in 3 different forms: monomers, disulfide-linked homodimers, and NGAL–gelatinase B complexes.32 Nonreducing SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining before (lane 2) and after (lane 3) removal of the NGAL–gelatinase B complex allows visualization of the positions of the monomers, the dimers, and the NGAL–gelatinase B complexes. After chemical reduction with β-mercaptoethanol, the dimer was dissociated into monomers in the electrophoretically pure preparation (lane 4). Relative molecular masses of the monomer, heterodimer, and homodimer were estimated to be 91, 125 and greater than 200 kd by comparison with the molecular mass markers (lane 1).

Processing of chemokines by gelatinase B

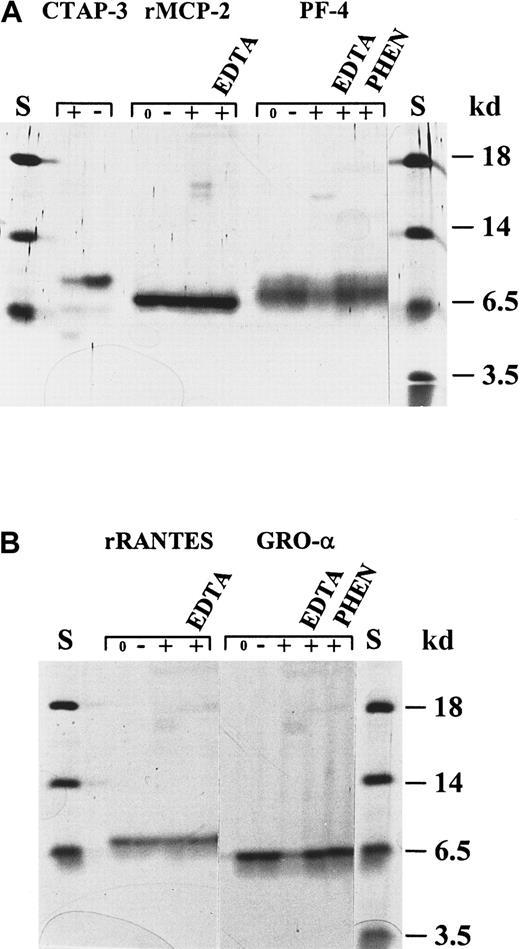

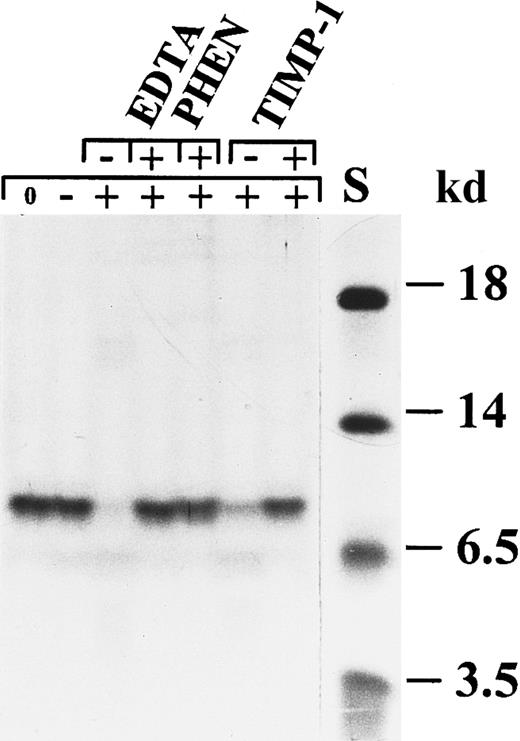

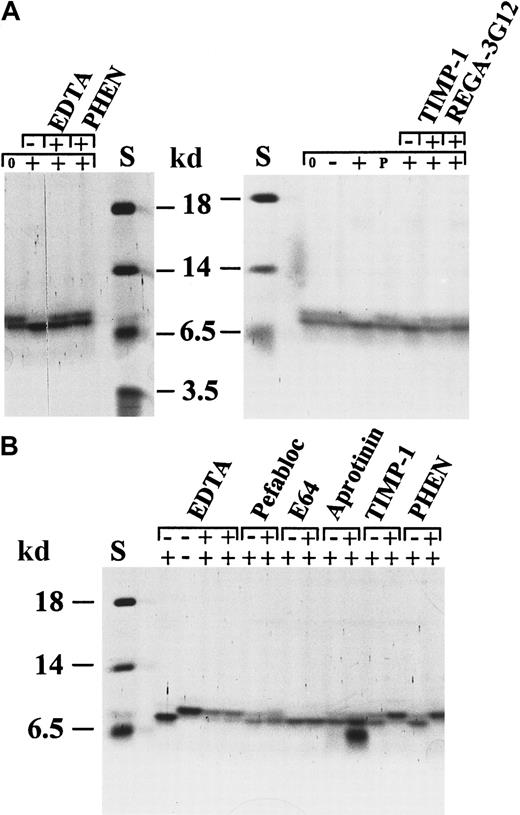

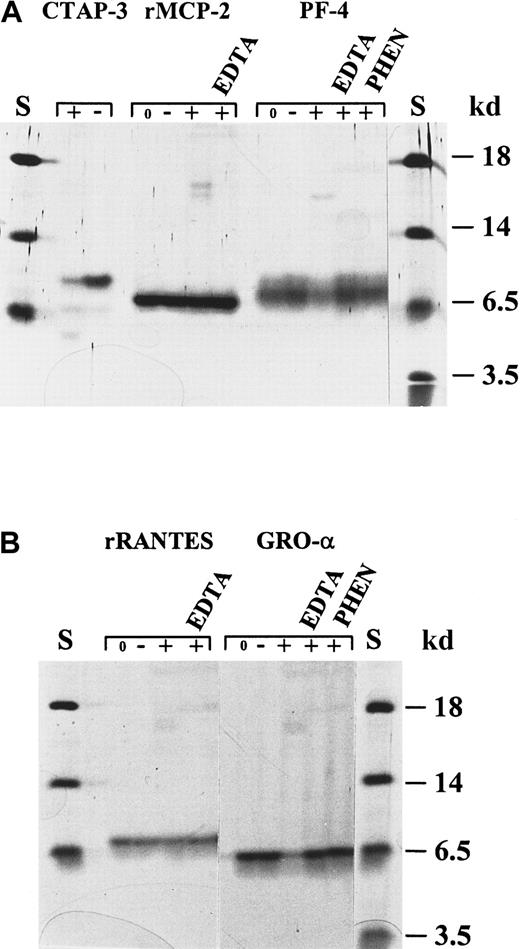

To investigate whether chemokines are processed by gelatinase B, different CXC and CC chemokines were incubated with pure activated neutrophil gelatinase B at 37°C for several time intervals (enzyme–substrate molar ratio, 1:10). Subsequently, the digestion products were identified by SDS-PAGE, aminoterminal sequencing, and mass spectrometry analysis. Two members of the CC chemokine family, RANTES and MCP-2, were not cleaved by gelatinase B (Figure2). PF-4, an ELR-negative CXC chemokine, and GRO-α, an ELR motif-containing CXC chemokine, were slowly degraded by gelatinase B; the conversions were still incomplete after a 24-hour incubation period (Figure 2). By aminoterminal sequence analysis, at least 2 gelatinase B cleavage sites could be identified in GRO-α, namely in front of Leu at position 7 (L7RCQCLQ…) and in front of Val at position 28 (V28KSPG…). CTAP-III was also degraded by gelatinase B (Figures 2, 3), and multiple cleavage sites were identified (Figure 4). To obtain this detailed information, the CTAP-III peptides were fractionated by RP-HPLC, and the individual fractions were analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS and MS/MS), protein sequence analysis, or both. Incubation of natural or recombinant IL-8(1-77) with gelatinase B resulted in the efficient removal of only 6 aminoterminal residues and, thus, in the formation of IL-8(7-77) with A7KELR… as the aminoterminal sequence (Figure 5, Table 1). Both IL-8 forms, intact and truncated, were analyzed by mass spectrometry, confirming the identity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) and excluding carboxyterminal processing of IL-8 by gelatinase B (Figure 6). IL-8(6-77) (S6AKELR…), present in the natural IL-8 preparations in addition to IL-8(1-77), was not converted by gelatinase B to IL-8(7-77), which is consistent with the fact that gelatinase B is not an exopeptidase (Table 1).

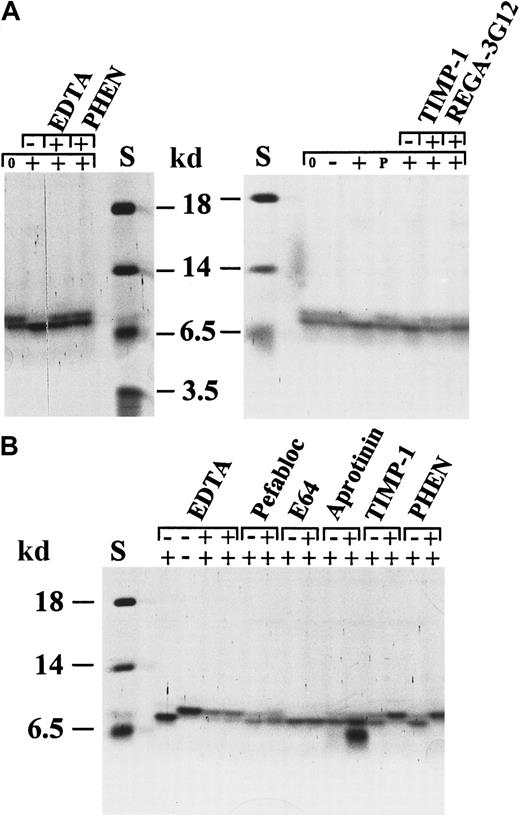

Processing of the chemokines CTAP-III, MCP-2, PF-4, RANTES, and GRO-α by activated neutrophil gelatinase B.

Different chemokines were incubated with activated gelatinase B and subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. (A) Recombinant human MCP-2 was not affected by treatment with gelatinase B. Natural human CTAP-III and PF-4 were slowly degraded by gelatinase B. Degradation of PF-4 was inhibited by EDTA and o-phenantrolin (PHEN) and was not observed after incubation with stromelysin-1 alone. (B) Recombinant RANTES was not affected by incubation with gelatinase B, whereas natural GRO-α was slowly degraded. Degradation of GRO-α was inhibited by EDTA and PHEN and was not observed after incubation with stromelysin-1. S indicates relative molecular mass standard; 0, no incubation; −, incubation with stromelysin-1 only; +, incubation with activated gelatinase B. Respective inhibitors are indicated at the top of each lane.

Processing of the chemokines CTAP-III, MCP-2, PF-4, RANTES, and GRO-α by activated neutrophil gelatinase B.

Different chemokines were incubated with activated gelatinase B and subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. (A) Recombinant human MCP-2 was not affected by treatment with gelatinase B. Natural human CTAP-III and PF-4 were slowly degraded by gelatinase B. Degradation of PF-4 was inhibited by EDTA and o-phenantrolin (PHEN) and was not observed after incubation with stromelysin-1 alone. (B) Recombinant RANTES was not affected by incubation with gelatinase B, whereas natural GRO-α was slowly degraded. Degradation of GRO-α was inhibited by EDTA and PHEN and was not observed after incubation with stromelysin-1. S indicates relative molecular mass standard; 0, no incubation; −, incubation with stromelysin-1 only; +, incubation with activated gelatinase B. Respective inhibitors are indicated at the top of each lane.

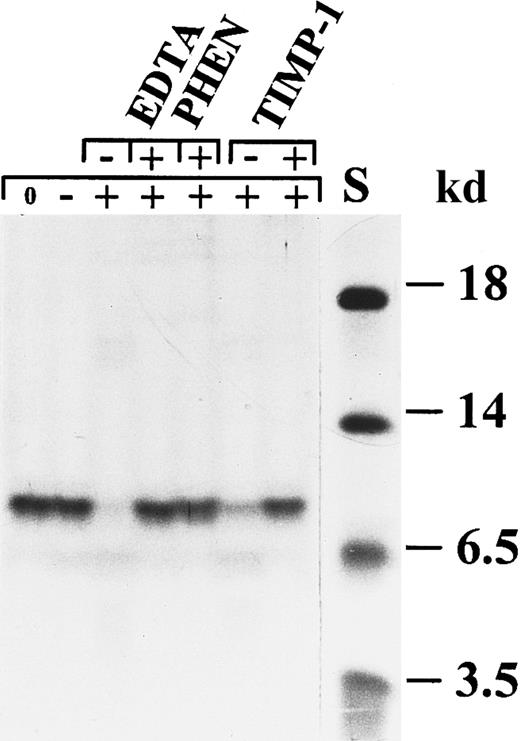

Degradation of CTAP-III by activated neutrophil gelatinase B.

CTAP-III was incubated with activated gelatinase B in the presence or absence of the metalloproteinase inhibitors EDTA,o-phenantrolin (PHEN), and TIMP-1. The 3 inhibitors separately inhibited the degradation completely. Stromelysin-1 alone was not able to degrade CTAP-III. S indicates molecular mass standard. The symbols + and − in the upper line indicate the presence or absence of the indicated inhibitors, whereas the symbols 0, −, and + in the line underneath indicate no incubation, incubation with stromelysin-1 alone, and incubation with stromelysin-1–activated gelatinase B, respectively.

Degradation of CTAP-III by activated neutrophil gelatinase B.

CTAP-III was incubated with activated gelatinase B in the presence or absence of the metalloproteinase inhibitors EDTA,o-phenantrolin (PHEN), and TIMP-1. The 3 inhibitors separately inhibited the degradation completely. Stromelysin-1 alone was not able to degrade CTAP-III. S indicates molecular mass standard. The symbols + and − in the upper line indicate the presence or absence of the indicated inhibitors, whereas the symbols 0, −, and + in the line underneath indicate no incubation, incubation with stromelysin-1 alone, and incubation with stromelysin-1–activated gelatinase B, respectively.

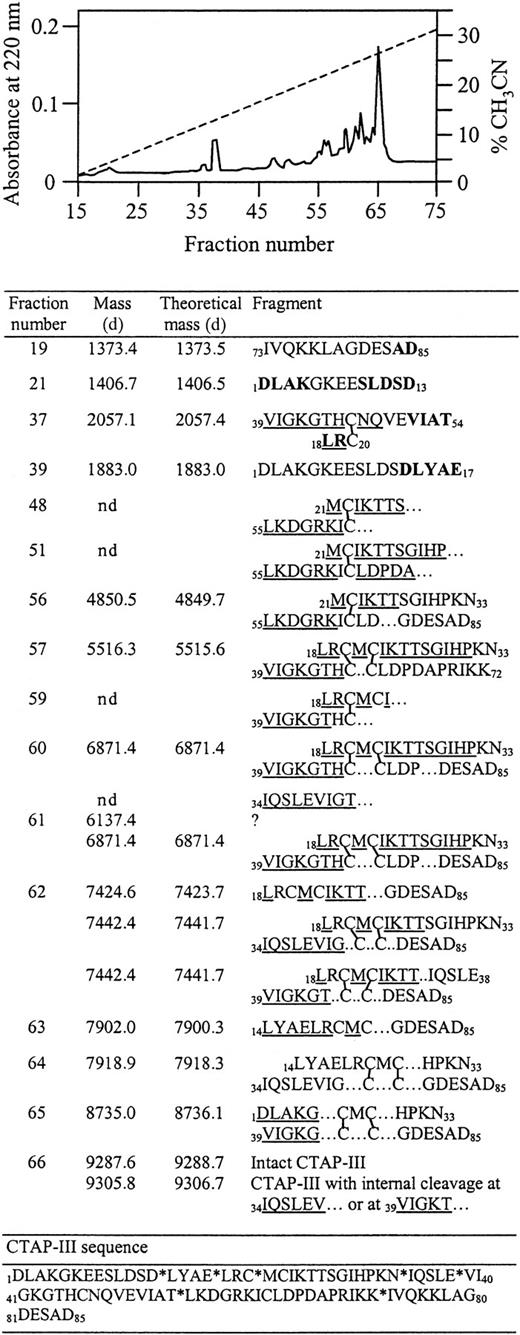

Determination of the cleavage sites in CTAP-III by gelatinase B.

After digestion of CTAP-III with gelatinase B, the reaction mixture was subjected to reverse-phase HPLC on a C8 column to separate the cleavage products into different fractions (top). Peptides were identified by aminoterminal sequencing and mass spectrometry analysis (bottom). Sequences in bold letters were determined by tandem MS/MS, and underlined sequences were determined by Edman degradation. Intact disulfide bridges (as determined by MS analysis) are indicated by lines between the cysteine pairs. The experimentally determined molecular mass of the fragments is compared with the calculated theoretical mass data. Positions of the cleavage sites are indicated by asterisks in the sequence of CTAP-III (lowest part of bottom panel). nd, not detectable.

Determination of the cleavage sites in CTAP-III by gelatinase B.

After digestion of CTAP-III with gelatinase B, the reaction mixture was subjected to reverse-phase HPLC on a C8 column to separate the cleavage products into different fractions (top). Peptides were identified by aminoterminal sequencing and mass spectrometry analysis (bottom). Sequences in bold letters were determined by tandem MS/MS, and underlined sequences were determined by Edman degradation. Intact disulfide bridges (as determined by MS analysis) are indicated by lines between the cysteine pairs. The experimentally determined molecular mass of the fragments is compared with the calculated theoretical mass data. Positions of the cleavage sites are indicated by asterisks in the sequence of CTAP-III (lowest part of bottom panel). nd, not detectable.

Specific conversion of IL-8(1-77) to IL-8(7-77) by activated neutrophil gelatinase B.

Natural IL-8 occurs as 2 protein variants, IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(6-77), which are separable by SDS-PAGE. Activated gelatinase B processes natural (A) and recombinant (B) human IL-8(1-77) to a shorter form, identified as IL-8(7-77) (Table 1). To illustrate that this conversion was by activated gelatinase B, various inhibitors were tested for their ability to inhibit the chemokine conversion. The metalloproteinase inhibitors EDTA, o-phenantrolin (PHEN), and TIMP-1 and the gelatinase B–inhibiting monoclonal antibody REGA-3G12 inhibited this conversion completely, but no effect was visible with the serine protease inhibitors pefabloc and aprotinin or with the thiolprotease inhibitor E64. Progelatinase B or stromelysin-1 alone was unable to process IL-8. In B, the first 2 lanes (with the controls of the EDTA inhibition) contain twice the amount of IL-8 as the other lanes. S indicates relative molecular mass standard. The + and − symbols in the upper line indicate the presence or absence of the indicated inhibitors, whereas symbols 0, −, +, or P in the lower line indicate no incubation, incubation with stromelysin-1 alone, incubation with activated gelatinase B, or incubation with progelatinase B, respectively.

Specific conversion of IL-8(1-77) to IL-8(7-77) by activated neutrophil gelatinase B.

Natural IL-8 occurs as 2 protein variants, IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(6-77), which are separable by SDS-PAGE. Activated gelatinase B processes natural (A) and recombinant (B) human IL-8(1-77) to a shorter form, identified as IL-8(7-77) (Table 1). To illustrate that this conversion was by activated gelatinase B, various inhibitors were tested for their ability to inhibit the chemokine conversion. The metalloproteinase inhibitors EDTA, o-phenantrolin (PHEN), and TIMP-1 and the gelatinase B–inhibiting monoclonal antibody REGA-3G12 inhibited this conversion completely, but no effect was visible with the serine protease inhibitors pefabloc and aprotinin or with the thiolprotease inhibitor E64. Progelatinase B or stromelysin-1 alone was unable to process IL-8. In B, the first 2 lanes (with the controls of the EDTA inhibition) contain twice the amount of IL-8 as the other lanes. S indicates relative molecular mass standard. The + and − symbols in the upper line indicate the presence or absence of the indicated inhibitors, whereas symbols 0, −, +, or P in the lower line indicate no incubation, incubation with stromelysin-1 alone, incubation with activated gelatinase B, or incubation with progelatinase B, respectively.

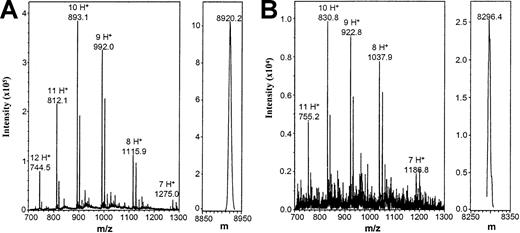

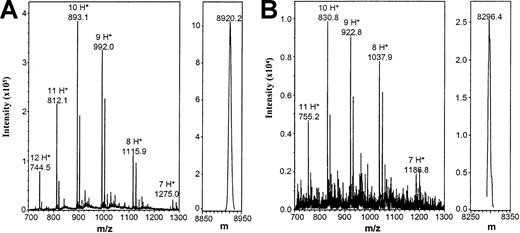

Mass spectrometry analysis of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77).

IL-8(1-77) (A) and IL-8(7-77) (B) were desalted and subjected to electrospray mass spectrometry analysis to exclude the possibility of carboxyterminal cleavage by gelatinase B. Unprocessed (m/z) and charge-deconvoluted (m) spectra are shown. Theoretical masses of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) are 8922.5 d and 8298.7 d, respectively. In the left panels, the m/z values for the differently charged ions are indicated, as are the number of protons (H+) they carry.

Mass spectrometry analysis of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77).

IL-8(1-77) (A) and IL-8(7-77) (B) were desalted and subjected to electrospray mass spectrometry analysis to exclude the possibility of carboxyterminal cleavage by gelatinase B. Unprocessed (m/z) and charge-deconvoluted (m) spectra are shown. Theoretical masses of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) are 8922.5 d and 8298.7 d, respectively. In the left panels, the m/z values for the differently charged ions are indicated, as are the number of protons (H+) they carry.

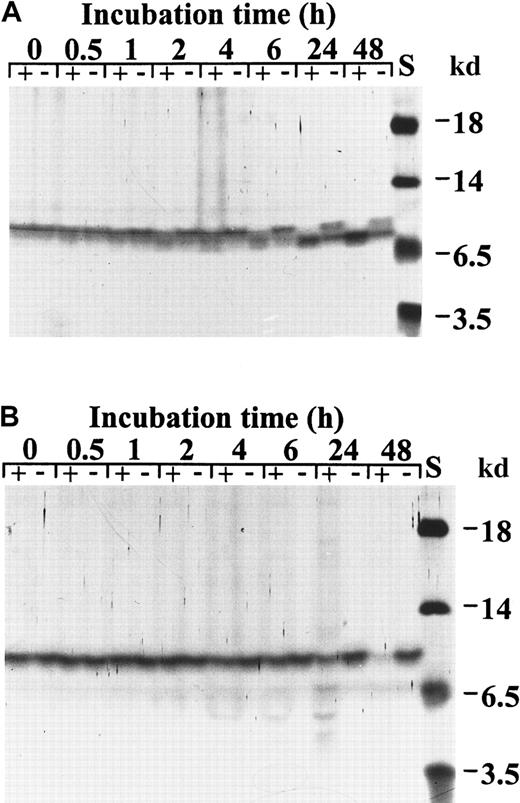

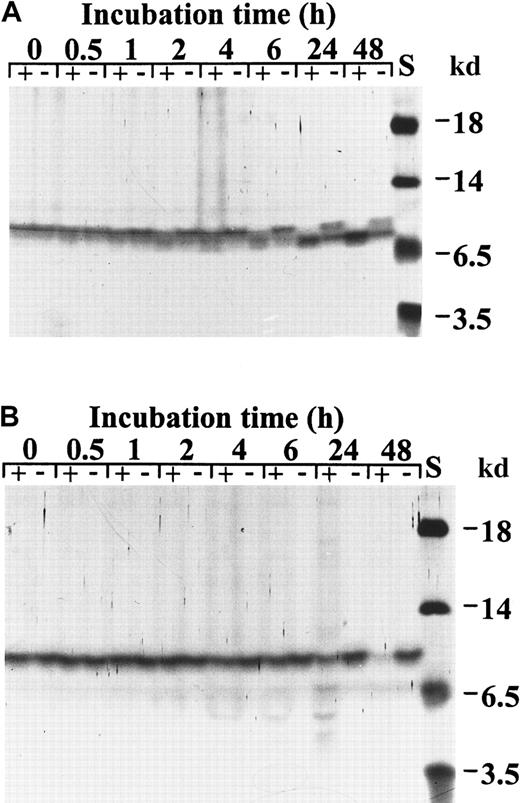

The kinetics of the cleavage of IL-8 and CTAP-III were also compared, and IL-8 was found to be processed more efficiently, with IL-8(7-77) already appearing after 1 hour of incubation and reaching 100% conversion after 24 hours. In contrast, the first cleavage products of CTAP-III appeared only after 2 hours, and the degradation was only completed after 48 hours (Figure 7).

Time course of the degradation of IL-8 and CTAP-III by activated gelatinase B.

Recombinant IL-8 (A) and natural CTAP-III (B) (both at 4 μmol/L) were incubated with activated neutrophil gelatinase B (0.4 μmol/L) at 37°C. A control sample was incubated with activated stromelysin-1 (0.004 μmol/L). Samples were taken at the indicated time intervals and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. S indicates relative molecular mass standard; the symbols − and + indicate incubation with stromelysin-1 alone and with activated gelatinase B, respectively.

Time course of the degradation of IL-8 and CTAP-III by activated gelatinase B.

Recombinant IL-8 (A) and natural CTAP-III (B) (both at 4 μmol/L) were incubated with activated neutrophil gelatinase B (0.4 μmol/L) at 37°C. A control sample was incubated with activated stromelysin-1 (0.004 μmol/L). Samples were taken at the indicated time intervals and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. S indicates relative molecular mass standard; the symbols − and + indicate incubation with stromelysin-1 alone and with activated gelatinase B, respectively.

To ascertain further that the observed cleavages were performed by the metalloproteinase gelatinase B, various types of inhibition studies were performed (Figures 2,3,5). For instance, the conversions of natural or recombinant IL-8 preparations were inhibited by the matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors EDTA, o-phenantrolin, TIMP-1, and by a specific gelatinase B–inhibiting monoclonal antibody (REGA-3G12),30 but not by the inhibitors for serine (pefabloc, aprotinin) or thiol proteases (E64) (Figure 5). The IL-8 conversion was not caused by the activated stromelysin-1 (used to convert progelatinase B into active gelatinase B), because control incubations with stromelysin-1 did not result in substrate cleavage. Finally, progelatinase B in its latent form did not process IL-8, which illustrates that the activation of progelatinase B is necessary for aminoterminal clipping of IL-8.

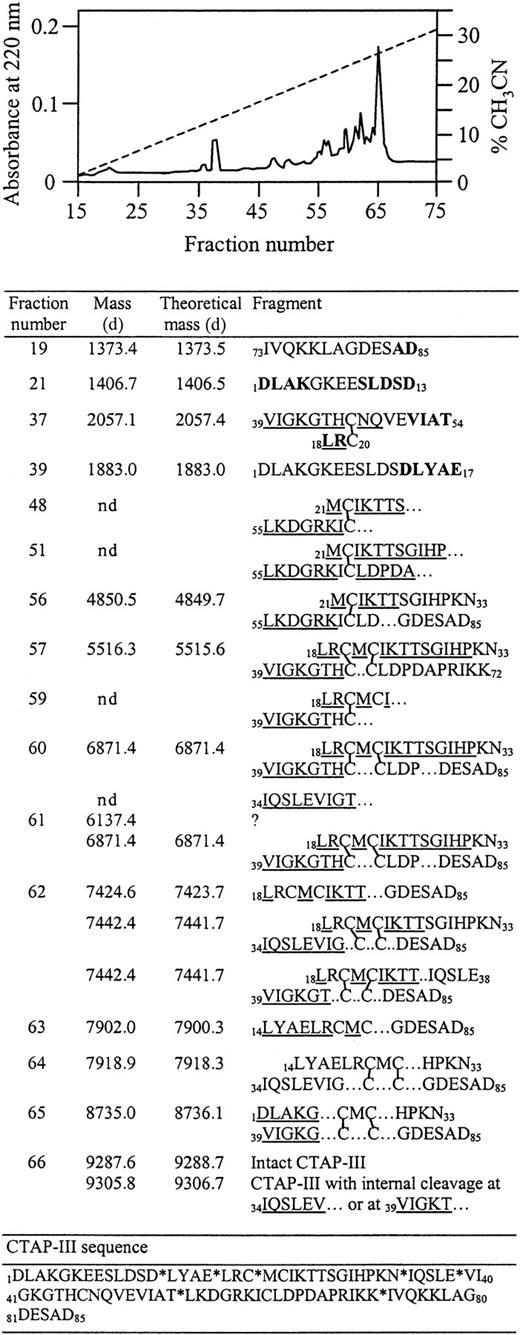

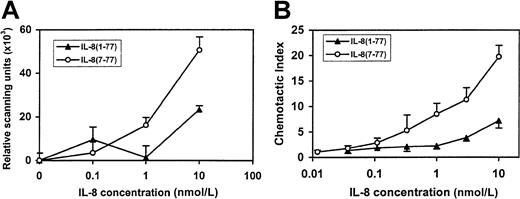

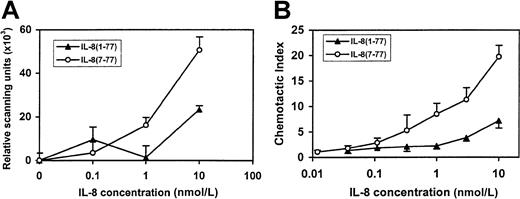

Effect of the processing by gelatinase B on the biologic activity of IL-8

Recombinant human IL-8(1-77) was converted by activated gelatinase B to IL-8(7-77), and the latter was repurified by reverse-phase HPLC. First, binding experiments were performed to compare the relative affinities of both IL-8 forms for their receptors on the surfaces of neutrophilic granulocytes. In comparison with intact IL-8(1-77), half-maximal binding of IL-8(7-77) on neutrophils was observed at concentrations more than 10 times lower (Figure8). In addition, the biologic activities of both IL-8 forms, IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77), were compared on neutrophilic granulocytes. Signal transduction by IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) through neutrophil receptors was analyzed by measuring the increase of [Ca++]i. It was found that IL-8(7-77) mobilized intracellular Ca++ at concentrations more than 20 times lower (minimal effective concentration, 0.018 nmol/L) than IL-8(1-77) (minimal effective concentration, 0.5 nmol/L) (Figure 8). Finally, degranulation and chemotaxis assays were performed on neutrophils (Figure9). A significant release of gelatinase B was induced by IL-8(7-77) at 1 nmol/L, whereas 10 nmol/L IL-8(1-77) was required to obtain a similar effect. This difference in potency was even more pronounced in neutrophil chemotaxis assays. IL-8(7-77) induced neutrophil chemotaxis from 0.1 nmol/L onward, whereas the minimal effective concentration of IL-8(1-77) was 2.7 nmol/L. In all 4 assays (binding, [Ca++]i-increase, gelatinase B release, and chemotaxis), it was reproducibly shown that IL-8(7-77) was 14, 27, 10, and 27 times, respectively, more active on neutrophils than IL-8(1-77).

Binding to and intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in neutrophils.

(A) Relative binding properties of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) to human neutrophils were compared. Neutrophils were incubated with125I–IL-8(6-77) and various concentrations of unlabeled IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77). The decrease in cell-bound radioactivity was used as a measure for competition by the unlabeled IL-8 forms and thus for their affinity to the cells. Mean and SEM (n = 4) are indicated. (B) Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were determined by measurement of the fluorescence of the dye fura-2 during stimulation with the IL-8 forms. One representative experiment of 2 is shown. Successive one-third dilutions of both IL-8 forms were analyzed until no increase of [Ca++]i could be measured. The detection limit in [Ca++]i increase was 15 nmol/L. Stimulation with IL-8(1-77) at 0.17 nmol/L and IL-8(7-77) at 0.006 nmol/L resulted in a [Ca++]i increase below the detection limit.

Binding to and intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in neutrophils.

(A) Relative binding properties of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) to human neutrophils were compared. Neutrophils were incubated with125I–IL-8(6-77) and various concentrations of unlabeled IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77). The decrease in cell-bound radioactivity was used as a measure for competition by the unlabeled IL-8 forms and thus for their affinity to the cells. Mean and SEM (n = 4) are indicated. (B) Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were determined by measurement of the fluorescence of the dye fura-2 during stimulation with the IL-8 forms. One representative experiment of 2 is shown. Successive one-third dilutions of both IL-8 forms were analyzed until no increase of [Ca++]i could be measured. The detection limit in [Ca++]i increase was 15 nmol/L. Stimulation with IL-8(1-77) at 0.17 nmol/L and IL-8(7-77) at 0.006 nmol/L resulted in a [Ca++]i increase below the detection limit.

Gelatinase B release and chemotactic activities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77).

(A) Purified granulocytes were incubated with various concentrations of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) for 30 minutes to induce the release of gelatinase B. Gelatinase B in the culture fluid of stimulated cells was analyzed by substrate zymography, quantified by scanning densitometry, and expressed in scanning units after the subtraction of background levels. Results are indicated as the mean (±SEM) of 3 independent experiments with neutrophil preparations from different donors. (B) The chemotactic activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) for neutrophils was compared in a modified Boyden chemotaxis chamber. Chemotactic indices are shown as the mean and the standard errors of mean of 4 independent experiments with cell preparations from different donors.

Gelatinase B release and chemotactic activities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77).

(A) Purified granulocytes were incubated with various concentrations of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) for 30 minutes to induce the release of gelatinase B. Gelatinase B in the culture fluid of stimulated cells was analyzed by substrate zymography, quantified by scanning densitometry, and expressed in scanning units after the subtraction of background levels. Results are indicated as the mean (±SEM) of 3 independent experiments with neutrophil preparations from different donors. (B) The chemotactic activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) for neutrophils was compared in a modified Boyden chemotaxis chamber. Chemotactic indices are shown as the mean and the standard errors of mean of 4 independent experiments with cell preparations from different donors.

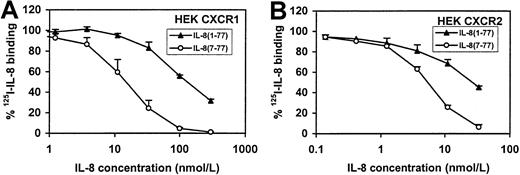

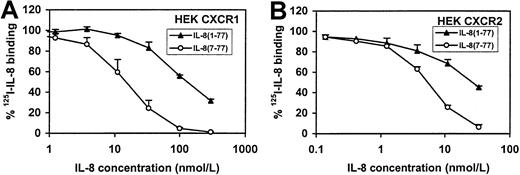

Because neutrophils have 2 IL-8 receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2,33 we analyzed the receptor-binding and intracellular Ca++-mobilizing capacities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) on both receptors separately. An anti-CXCR1 monoclonal antibody was found to inhibit both IL-8 forms in the intracellular Ca++-mobilization assay with neutrophils, showing that both IL-8 forms use at least CXCR1 (data not shown). Binding of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) to CXCR1 and CXCR2 were compared on cell lines separately transfected with either receptor (Figure10), whereas the effects of both ligands on intracellular Ca++-mobilization in CXCR transfectants are documented in Figure11. Our data on the receptor transfectants are in line with the data on human neutrophils and clearly show that both IL-8 forms use both receptor types. However, the difference in binding and intracellular Ca++-mobilizing capacity between IL-8(7-77) and IL-8(1-77) was 9-fold for CXCR1 transfectants, whereas for CXCR2 transfectants the difference (2.5- to 4-fold) between IL-8(7-77) and IL-8(1-77) was significantly less pronounced (P < .05, Student t test) than for CXCR1.

Binding of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) to CXCR1- and CXCR2-transfected cell lines.

IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were compared for their ability to compete with 125I–IL-8(6-77) for binding (see legend to Figure 8) to CXCR1- and CXCR2-transfected HEK cell lines (A and B, respectively). Mean and SEM (n = 4) are indicated.

Binding of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) to CXCR1- and CXCR2-transfected cell lines.

IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were compared for their ability to compete with 125I–IL-8(6-77) for binding (see legend to Figure 8) to CXCR1- and CXCR2-transfected HEK cell lines (A and B, respectively). Mean and SEM (n = 4) are indicated.

Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in CXCR1- and CXCR2-transfected cell lines.

Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing capacities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were compared on cell lines transfected with CXCR1 and CXCR2. In both cell lines, IL-8(7-77) was more active than IL-8(1-77), but this difference was more pronounced in CXCR1- (A) than in CXCR2- (B) transfected cell lines (P < .05). One representative experiment of 3 is shown. Successive one-third dilutions of both IL-8 forms were analyzed until no increase in [Ca++]i could be measured. Detection limits in [Ca++]i increase were 50 and 20 nmol/L for CXCR1 and CXCR2 transfectants, respectively. For each IL-8 variant and CXCR interaction, dosages giving a response below the detection limit of the [Ca++]i increase were included.

Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in CXCR1- and CXCR2-transfected cell lines.

Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing capacities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were compared on cell lines transfected with CXCR1 and CXCR2. In both cell lines, IL-8(7-77) was more active than IL-8(1-77), but this difference was more pronounced in CXCR1- (A) than in CXCR2- (B) transfected cell lines (P < .05). One representative experiment of 3 is shown. Successive one-third dilutions of both IL-8 forms were analyzed until no increase in [Ca++]i could be measured. Detection limits in [Ca++]i increase were 50 and 20 nmol/L for CXCR1 and CXCR2 transfectants, respectively. For each IL-8 variant and CXCR interaction, dosages giving a response below the detection limit of the [Ca++]i increase were included.

Discussion

IL-8, the most potent neutrophil-activating chemokine, stimulates the release of gelatinase B from neutrophils.1 Here it is demonstrated that gelatinase B processes IL-8 and other CXC chemokines and alters the specific activities and receptor usage. The best-known substrates for gelatinase B are denatured collagens (gelatins). Collagen types V and XI can also be cleaved by gelatinase B; however, it is unclear whether gelatinase B can cleave native full-length type IV collagen.34,35 Other extracellular matrix substrates include aggrecan,36 link protein,37 and elastin.38 Gelatinase B was also shown to degrade myelin basic protein, resulting in the release of encephalitogenic peptides.39 In addition to these structural components, other gelatinase B substrates are functional proteins. These include the serine-protease inhibitors α1-proteinase inhibitor, α1-antitrypsin, α1-antichymotrypsin,40,41 substance P,42 galactoside-binding proteins CBP30 and CBP35,43,44 and IL-1β, the latter of which is activated by gelatinase B.45

We report for the first time that several CXC chemokines, but not the CC chemokines RANTES and MCP-2, are substrates for activated gelatinase B. CTAP-III was degraded by gelatinase B, and 7 different cleavage sites were identified. In contrast, IL-8(1-77) was aminoterminally truncated by gelatinase B to IL-8(7-77). The effects of this selective cleavage were reflected by the enhanced biologic activities of IL-8 and mediated more through CXCR1 and less through CXCR2. We propose that a more than 10-fold increase in neutrophil activation by truncated IL-8 has consequences not only for chemotaxis but for other processes mediated by IL-8, such as leukocytosis regulation, stem cell mobilization, and (septic) shock syndromes characterized by high circulating levels of IL-846 and gelatinase B.47

Different aminoterminally processed forms of IL-8 from natural sources have been previously described. Endothelial cells and fibroblasts produce mainly IL-8(1-77), whereas mononuclear leukocytes produce mainly IL-8(6-77).48-51 Other natural forms of IL-8 also exist, and these include IL-8(2-77), IL-8(7-77), IL-8(8-77), and IL-8(9-77).15,48 Thrombin50 and plasmin52 have been shown to convert IL-8(1-77) to IL-8(6-77), whereas proteinase-3 from neutrophils cleaves IL-8(1-77) to produce IL-8(8-77).53 In general, shorter forms of IL-8 have been shown to be more active than longer forms, provided that the ELR motif remains intact. Compared to IL-8(1-77), IL-8(6-77) was shown to be 2 to 10 times more active in binding to neutrophils and in inducing the adhesion of neutrophils, chemotaxis, and degranulation.50,53-55 IL-8(8-77) and IL-8(9-77) were shown to be even more active than IL-8(6-77), but shorter forms, lacking an intact ELR motif, are inactive.54

Here it is shown that natural and recombinant IL-8(1-77) can be converted efficiently to IL-8(7-77) by activated neutrophil gelatinase B. This conversion is physiologically relevant because IL-8(7-77) has been recovered from leukocytes and fibroblasts15,48 and because IL-8 is able to induce degranulation of the specific and gelatinase B–containing granules from neutrophils.1,56 In contrast, azurophilic granules—containing, for example, proteinase-3, elastase, and cathepsin G—are not released on stimulation of neutrophils with IL-8 in the absence of synthetic cytochalasin B.56

In addition, IL-8(7-77) was found to be 10 to 27 times more active on human neutrophils than IL-8(1-77), as shown in binding experiments, [Ca++]i measurements, degranulation, and chemotaxis assays. This difference is more pronounced than that found by Nourshargh et al55 with IL-8(6-77) in comparison with IL-8(1-77) on rabbit neutrophils, but it is similar to the difference described by Schröder et al51 with IL-8(6-77) and IL-8(1-77) on human neutrophils. Because neutrophils contain both IL-8 receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, and because it was not yet known on which receptor the shorter IL-8 forms are more active, we also studied the Ca++-mobilizing activities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in cell lines transfected with CXCR1 or CXCR2. In CXCR1 transfectants, the difference (9-fold) in binding and Ca++-mobilization between IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) is in the same order as the difference observed in neutrophils. However, on CXCR2-transfected cells, IL-8(7-77) is only about 2.5 to 4 times more active than IL-8(1-77). Although it is uncertain that the binding of the chemokine to the receptors and the signal transduction are the same in normal cells as in transfectants, our results suggest that the aminoterminal truncation of IL-8 mainly affects binding and signaling through CXCR1. The biologic effect of the cleavage of IL-8 by gelatinase B may, therefore, be different for various target cell types. Indeed, some cell types are shown to contain predominantly one of either of the IL-8 receptors. For instance, the chemotaxis of mast cells in response to IL-8 is mediated through CXCR2 and not through CXCR1.57 Moreover, different functions have been ascribed to the 2 CXC chemokine-receptors on neutrophils. This implies that the effect of the truncation of IL-8 on its activity may vary, depending on the IL-8–induced function. For instance, though chemotaxis in response to GRO-α is mediated through CXCR2, it is not yet clear whether the chemotaxis in response to IL-8 is mediated through one or both receptors. Initially, it was shown to be mediated mainly through CXCR1,58 but the affinity of IL-8 for CXCR2 was found to be higher than for CXCR1, indicating that CXCR2 might be more important at low IL-8 concentrations.59 Other authors could not find any difference between CXCR1 and CXCR2 signaling for chemotaxis, granule release, or activation of mitogen-activating protein kinase in response to IL-8, but they reported that the induction of respiratory burst and phospholipase D activity in neutrophils is mediated only through CXCR1 and not through CXCR2.60-62 Interestingly, CXCR2 is strongly down-regulated during sepsis,63 so that neutrophil function may then become dependent on signaling through CXCR1.

Proteolytic activity of gelatinase B toward other chemokine substrates was also investigated. The CXC chemokines PF-4, GRO-α, and CTAP-III were slowly degraded, whereas the CC chemokines RANTES and MCP-2 were not affected by incubation with gelatinase B. Thus, gelatinase B seems to exercise a positive feedback loop on the IL-8–mediated triggering of neutrophils, mediated mainly through CXCR1. In contrast, for other ELR-positive CXC chemokines (CTAP-III, GRO-α), a negative effect is created by the degradation of these chemokines by gelatinase B. Interestingly, a serine protease from the azurophilic granules of the neutrophil, cathepsin G, has the opposite effect, because it degrades IL-8 slowly53 but activates ENA-7819 and converts CTAP-III to the CXCR2 ligand NAP-2.17Furthermore, it was recently shown that, after stimulation of neutrophils with lipopolysaccharide or tumor necrosis factor-α, CXCR1 and CXCR2 are down-regulated by proteolysis by a yet unidentified metalloproteinase. Finally, it is known that both receptors are internalized by neutrophils after activation with IL-8.64

The neutrophil is a terminally differentiated phagocyte that contains enzymes for target cell killing and for degradation of extracellular matrix components. Activation of neutrophils by CXC chemokines such as IL-8 leads to the secretion of proteases including gelatinase B. Our results show that the predominant member of the matrix metalloproteinases in neutrophils, gelatinase B, also contributes to enhanced IL-8 activity by a positive feedback loop. This finding is not only relevant to better understand physiopathological processes such as pyogenic infections and sepsis, it is relevant for clinical applications such as stem cell mobilization, in which both gelatinase B65 and IL-866 67 are involved.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sofie Struyf for her scientific contributions and René Conings, Jean-Pierre Lenaerts, and Willy Put for experimental help. We thank the F.W.O.-Vlaanderen for its support in acquiring the mass spectrometry equipment.

Supported by the Fortis Insurances AB, the Charcot Foundation, the “Geconcerteerde OnderzoeksActies,” and the National Fund for Scientific Research (F.W.O.-Vlaanderen), Belgium. P.V.d.S. is a research assistant and P.P. is a postdoctoral fellow of the F.W.O.-Vlaanderen.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Ghislain Opdenakker, Laboratory of Molecular Immunology, Rega Institute for Medical Research, University of Leuven, Minderbroedersstraat 10, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium.

![Fig. 8. Binding to and intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in neutrophils. / (A) Relative binding properties of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) to human neutrophils were compared. Neutrophils were incubated with125I–IL-8(6-77) and various concentrations of unlabeled IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77). The decrease in cell-bound radioactivity was used as a measure for competition by the unlabeled IL-8 forms and thus for their affinity to the cells. Mean and SEM (n = 4) are indicated. (B) Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were determined by measurement of the fluorescence of the dye fura-2 during stimulation with the IL-8 forms. One representative experiment of 2 is shown. Successive one-third dilutions of both IL-8 forms were analyzed until no increase of [Ca++]i could be measured. The detection limit in [Ca++]i increase was 15 nmol/L. Stimulation with IL-8(1-77) at 0.17 nmol/L and IL-8(7-77) at 0.006 nmol/L resulted in a [Ca++]i increase below the detection limit.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/96/8/10.1182_blood.v96.8.2673/5/m_h82000242008.jpeg?Expires=1767728576&Signature=OdpbtTJHdfhinjkM5OFlfIb92Q98ghCiZxPIYpAUUwnoU8R9C4gh3PkTklcRajwNNiW-ybI2iY2rVmYTFow902hyCYOYR09M8XLI-jad9lf9gGp9AIpe61AumehIa5imiOnYUyQY4n8vphPHiuPXF9eQv-rERh3IMo3hGTFx~8ehhEveRyZ34hSev4Q9~Wlsrb5-wp67NyugG12bMsMkviabS4X4uDH7ok9Q3lNfXGO~G6jV1J9vWqQxap8in5hxnp~7BbwMRCSmv84ccoEe5y7F8x-t1JVsiCd3uMq0Pb7OT2vWcIMqVNhNAhWcMbNiLN5jkE1AoYodLfpSmx1f~w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 11. Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in CXCR1- and CXCR2-transfected cell lines. / Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing capacities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were compared on cell lines transfected with CXCR1 and CXCR2. In both cell lines, IL-8(7-77) was more active than IL-8(1-77), but this difference was more pronounced in CXCR1- (A) than in CXCR2- (B) transfected cell lines (P < .05). One representative experiment of 3 is shown. Successive one-third dilutions of both IL-8 forms were analyzed until no increase in [Ca++]i could be measured. Detection limits in [Ca++]i increase were 50 and 20 nmol/L for CXCR1 and CXCR2 transfectants, respectively. For each IL-8 variant and CXCR interaction, dosages giving a response below the detection limit of the [Ca++]i increase were included.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/96/8/10.1182_blood.v96.8.2673/5/m_h82000242011.jpeg?Expires=1767728576&Signature=DRJGZqQ8nFdWdviIfjFxCojN1wRZR0zhtK4zFD1bE70ywj-U2cw3gytP94ubzeV9Mcvp3P95r1n~4x1NiF1XmRZxY77rGlWCXP11SC6unZQSUIL2inyDCdrV0hotiG9uG6LdBxCwre0cOV5J3IRiUHYcUUjkNU~j7ISEj7bb~1EI8rk41ztDNZkcWFYiiJLMMQl6PhjnZe~cyV1UpIIMg0De~9SK5CP97IUTASgmDx3NWMAA9fWIlqbTYmZv~YMAMOjBzLuXnXSOFN14eHE3VQG6gAfGZJ7ThHm0rCMUI0q8bJ~0Ii25mGwM5TyOUBwr06Xn7E85qTP0NrCyXFQRNw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 8. Binding to and intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in neutrophils. / (A) Relative binding properties of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) to human neutrophils were compared. Neutrophils were incubated with125I–IL-8(6-77) and various concentrations of unlabeled IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77). The decrease in cell-bound radioactivity was used as a measure for competition by the unlabeled IL-8 forms and thus for their affinity to the cells. Mean and SEM (n = 4) are indicated. (B) Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were determined by measurement of the fluorescence of the dye fura-2 during stimulation with the IL-8 forms. One representative experiment of 2 is shown. Successive one-third dilutions of both IL-8 forms were analyzed until no increase of [Ca++]i could be measured. The detection limit in [Ca++]i increase was 15 nmol/L. Stimulation with IL-8(1-77) at 0.17 nmol/L and IL-8(7-77) at 0.006 nmol/L resulted in a [Ca++]i increase below the detection limit.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/96/8/10.1182_blood.v96.8.2673/5/m_h82000242008.jpeg?Expires=1768247524&Signature=I5Qir3GzBkN~qYdsQx84l~eB-00~FkpBzDFNz2sYLUS5qBEEIViCzcQuK7Hzzyv8mIJUxcIx2-xk371eceDv-cA4Man8BvKzlWt~FSDejqGGUF2RcFd24YogM0UAvDOBB6KgwLZd0joBC6TWgajF5D2O68BZviQHkJlEFqQL3-WoaV7t3QEJDyqZYU7oOMWUF3kR~ccxz8yS-2mjvpgPMBRzDQP73C0vlKsBTu3RmxOSgFYkANq0WT4PGGnWu6KCUl7UZKd60USNh2dEtN0MWyGhPvjesmCcBAMCq1AE~oInr~Ah7Qs6tU44gjMr00Im-ZL~kuGTGwIOXGPdz9AZLQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 11. Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing activity of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) in CXCR1- and CXCR2-transfected cell lines. / Intracellular Ca++-mobilizing capacities of IL-8(1-77) and IL-8(7-77) were compared on cell lines transfected with CXCR1 and CXCR2. In both cell lines, IL-8(7-77) was more active than IL-8(1-77), but this difference was more pronounced in CXCR1- (A) than in CXCR2- (B) transfected cell lines (P < .05). One representative experiment of 3 is shown. Successive one-third dilutions of both IL-8 forms were analyzed until no increase in [Ca++]i could be measured. Detection limits in [Ca++]i increase were 50 and 20 nmol/L for CXCR1 and CXCR2 transfectants, respectively. For each IL-8 variant and CXCR interaction, dosages giving a response below the detection limit of the [Ca++]i increase were included.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/96/8/10.1182_blood.v96.8.2673/5/m_h82000242011.jpeg?Expires=1768247524&Signature=gSDuPDiF8LdDMGUKtpA0KRpN~wvrW1DS-7VJ1kFNxFyGf1Zob-QuCmfDFc38fzD3K~YhtTSaoObw7jd4B0BKiVRRduy11x3LuXacsx6tld~QFMSiT8THFzGqwGL0JgedQPlUwfKPlRwoDG10nWIweJNeWAtmRA2mZL68A6z-mP5ToaJCLzYpM9A5fe58UFkq1uEljt4TMY~TvN~dXHnCdgy6J0eSn1mBf3PIfI6YZfDnkMF81lJwFpFNOtZdh6egTJnXa6zlL3PY5CapHh9ZbkOumGPWsmS-7wnA4EKfIHjd7VY7fi2RMNnVjU40G8V99t7K4UavxGa0-BmFC9gpJw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)