Abstract

Among high-grade malignant non-Hodgkin's lymphomas the updated Kiel classification identifies three major B-cell entities: centroblastic (CB), B-immunoblastic (B-IB), and B-large cell anaplastic (Ki-1+) (now termed anaplastic large cell [CD30+], [B-ALC]). The clinical prognostic relevance of this distinction was evaluated in a randomized prospective treatment trial (COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 regimen randomly combined ± radiotherapy in complete responders) conducted in adult (age 15 to 75) patients with Ann Arbor stage II-IV disease (n = 219) diagnosed by optimal histomorphology (Giemsa staining) and by immunohistochemistry. Overall survival was significantly better in CB lymphoma as compared to B-IB (P = .0002) or B-ALC (P = .046). Relapse-free survival was worse for B-IB (P = .0003) as compared to CB lymphomas. The prognostic differences between CB and B-IB were confirmed by multivariate analyses including the risk factors of the International Index. Overall survival was significantly determined by performance status (P = .0003), serum-LDH (P = .036), and B-IB histology subtype (P = .036). Relapse-free survival was influenced by age (P = .007) and histological subtype (P = .007). Thus, the diagnosis of the CB and B-IB lymphomas by the histological criteria of the Kiel classification was identified as an independent prognostic factor in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.

NON-HODGKIN'S lymphomas (NHLs) constitute a heterogenous group of neoplasms some of which can be cured if they are identified early, typed accurately, and treated adequately at the time of diagnosis. Therefore, a precise histological diagnosis is crucial for the clinical management and ultimately for the fate of the patient. However, there was sofar no international agreement on the appropriate classification of NHL and particularly on the clinical relevance of distinguishing certain lymphoma subtypes, an example of which will be examined here.

Within high-grade malignant NHL as defined by the updated Kiel classification1,2 three major subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas are identified, namely centroblastic (CB) and B-immunoblastic (B-IB) as well as B-large cell anaplastic (Ki-1+), which is now more commonly called anaplastic large cell (CD30+) lymphoma (B-ALC). The REAL classification recently proposed by the International Lymphoma Study Group (ILGS)3 combines these lymphomas in the single category of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. One reason given for this is that members in the ILSG were unable to come to uniform results in a small informal reproducability study. Another reason is the day-to-day experience of pathologists that large cell lymphomas are difficult to evaluate on routine histological sections.

The usefullness of this new classification system3 4 is currently assessed in clinical treatment trials. This approach which involves uniformly staged patients subjected to a standardized therapy offers the chance to determine whether or not the distinction of histomorphological subtypes of large B-cell lymphomas is of clinical prognostic relevance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients' characteristics.In a prospective randomized multicenter therapy trial patients aged 15 to 75 years with unpretreated Ann Arbor stage II-IV high-grade malignant NHL were diagnosed according to the updated Kiel classification1,2 and were treated with the COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 regimen in combination with or without adjuvant radiotherapy for complete responders. Preliminary results of the trial have already been reported.5 Between 1986 and 1989, 593 qualified patients (all types of B-, T-, and null-cell high-grade malignant NHL but excluding HIV-associated NHL) were finally recruited to the trial from 92 centers and surviving patients were followed for a median of 3.5 years. Subject of the present report is only a subset of 219 patients with selected B-type NHL meeting the diagnostic specifications outlined below.

Diagnosis.All biopsy specimens continuously sent to the Kiel lymph node registry during the recruitment phase of the trial were diagnosed immediately by the criteria of the Kiel classification (excluding all cases not meeting the study's requirements) and then immunophenotypically subtyped (M.T. and H.G.) and reviewed in the final analysis. The vast majority of morphological diagnoses was in concordance with those established in the final review by one investigator (K.L.).

In the histopathological review of all cases in which sufficient paraffin block specimens were supplied by the participating centers, high-quality Giemsa stainings were performed. Additionally, an immunophenotypic analysis characterizing the CD3, CD20, CD30, CD45RO antigenic determinants was done as well as specific staining for κ-, λ- , and/or μ-Ig chain restriction. Immunohistochemistry was performed with the avidin-biotin-peroxydase technique6 for polyclonal antibodies against CD3, κ-, λ- , and μ-Ig chains. Monoclonal antibodies directed against CD20, CD30, and CD45R0 were stained by the APAAP method.7 In 12 cases of B-ALC B-cell monoclonality was further confirmed by demonstration of clonal rearrangements of Ig CDR III gene locus and T-cell receptor γ chain with a polymerase chain reaction based technique.8 9

Every case accepted to the present analysis was required to be positive for CD20 (L26) as B marker and negative for CD3 and CD45R0 as T markers and/or negative for the β-chain of the T-cell receptor. Thus, all tumors were immunohistologically proven B-cell lymphomas.

The histological diagnosis was based on the updated Kiel classification.1 2 The main histological criteria were the following1: Centroblastic lymphoma consists of sheets of typical centroblasts: medium sized to large blasts with a narrow rim of basophilic cytoplasm, a large round or oval nucleus, and multiple medium sized nucleoli close to the nuclear membrane.

Four subgroups of centroblastic lymphoma can be distinguished morphologically: monomorphic (composed mainly of centroblasts), polymorphic (consisting of centroblasts, immunoblasts, and other not well-characterized blasts), multilobated (presenting high numbers of blasts with multilobated nuclei), and centrocytoid (containing cells morphologically reminiscent of centrocytes but exhibiting a coarser chromatin, larger nuclei, and, in contrast to centrocytes, a narrow pale cytoplasm). In simultaneous secondary centroblastic lymphoma the development of centroblastic-centrocytic lymphoma concurred with the transformation into subsequent centroblastic lymphoma and features of both are discernible within one specimen.

Because centrocytoid centroblastic lymphoma is now considered an aggressive variant of mantle cell lymphoma (with the exception of a few cases that may indeed be true CB) and because simultaneous secondary centroblastic lymphoma does not appear to be an exclusively de novo arising high-grade lymphoma, both of these entities are excluded from the comparative analysis of CB, B-IB, and B-ALC and are delt with separately.

The rare cases of follicular centroblastic lymphoma were not included in this study.

Immunoblastic lymphoma consists of sheets of large immunoblasts. The wide cytoplasm is intensely basophilic and the nuclei are quite monotonous. Typically, the nucleus has a solitary large or multiple, mostly centrally located nucleoli. In some cases plasmacytic differentiation occurs.

In anaplastic large cell lymphoma the tumor cells are larger and more irregular than immunoblasts and the cytoplasm is less basophilic. A further characteristic feature is the cohesive growth pattern of the blasts which can frequently only be recognized in the well-fixed areas of the slides.

The entire process of pathological investigations was done in Kiel without any knowledge of the clinical data. These were collected simultaneously in Essen but were analyzed only after the final diagnoses had been established.

Study design and therapy.The study was performed as a prospective multicenter randomized trial according to the following protocol: Chemotherapy consisted of a sequential application of the COP-BLAM regimen10 but without dosis escalation (cyclophosphamide 400 mg/m2 intravenous (i.v.), doxorubicin 40 mg/m2 i.v., and vincristine 1 mg/m2 i.v. on day 1, bleomycin15 mg i.v. absolute dose day 15, procarbazine 100 mg/m2 orally, and prednisone 40 mg/m2 orally day 1 to 10), and the IMVP-16 regimen11 (ifosphamide 1,000 mg/m2 i.v. day 1 to 5, methotrexate 30 mg/m2 i.v. day 1 and 10, and etoposide 100 mg/m2 i.v. day 1 to 3). Patients attaining complete remission (CR) after three cycles of COP-BLAM continued for another two cycles (total of 5) followed by two cycles of IMVP-16. Patients who achieved only a partial reponse (PR) after the initial three courses were immediately switched to three to five cycles of IMVP-16 regimen. Patients in CR after chemotherapy were randomized to receive adjuvant involved field or main bulk radiotherapy (40 Gy). Excluded from randomization were those patients who presented with bulky disease (≥10 cm lymphoma) for whom radiotherapy was recommended.

Statistical analysis.Survival probabilities (Kaplan-Meier estimation), significance of observed differences (log rank and chi square tests), and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors (Cox proportional hazards regression) were determined according to standard procedures.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.By optimal histomorphology, 164 (75%) of 219 cases analyzed were diagnosed to be CB, 33 (15%) were B-IB, and 22 (10%) were B-ALC lymphomas. In CB lymphoma, 21 (13%) belonged to the monomorphic, 74 (45%) to the polymorphic, 28 (17%) to the multilobated, and 18 (11%) to the centrocytoid subtypes. Nineteen cases (12%) were identified as simultaneous secondary CB; four (2%) were not further subtyped. Because centrocytoid and simultaneous secondary CB do not correspond to de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, these 37 cases were evaluated separately, leaving 127 cases of true CB in the comparative analysis with B-IB and B-ALC (total of 182 cases).

Pretreatment characteristics of all patients with CB, B-IB, and B-ALC lymphomas, including the incidences of risk factors established in the International Index12 and the resulting risk group assessment are summarized in Table 1. Some differences between the lymphoma subtypes appear to be noteworthy: Male predominance is prominent in B-IB (2.8:1), a poor performance status (Karnofsky index) was more frequent in B-IB, and the incidence of abnormal LDH-values higher in B-IB and B-ALC as compared to CB lymphomas. This accounts for the higher frequency of risk groups 3/4 in B-IB (55%) and B-ALC (49%) than in CB (35%). Further differences include the affinity to multiple extranodal manifestations in B-IB, partcularly skeleton and/or skin involvement in B-IB and B-ALC, and the tendency towards bone marrow infiltration in CB. However, none of these comparisons resulted in statistical significance.

Response.Response and survival data are given in Table 2. The CR rate (after completion of chemotherapy) was higher for CB (57%) than B-ALC (45%) or B-IB (42%) (P = .26) and the rate of relapse was significantly lower for CB (29%) or B-ALC (30%) than for B-IB (70%) lymphoma patients (P = . 010). Complete remissions accumulated in the low-risk group (Table 1) of the International Index but the CR rates in this subset were almost identical for CB (37/47 [79%]) and B-IB or B-ALC (5/6 [83%] each) patients. Dynamic of response was determined by the first restaging evaluation after 3 cycles and the second restaging after completion (mostly 7 cycles) of chemotherapy. In CB rapid CR was achieved more often (47%) than in B-IB (36%) or in B-ALC (23%). However, this did not correlate directly to the rates of relapse which were equally low in CB and B-ALC as opposed to B-IB lymphoma. Early relapse (within the second phase of therapy) was most frequent in B-IB (9%). Differences in the completion of protocol therapy (6-8 cycles) between CB (77%), B-IB (73%), and B-ALC (86%) lymphomas were only discrete, frequencies of adjuvant radiotherapy (25%, 50%, and 50%, respectively) moderately higher in B-IB and B-ALC), and average dose intensity achieved did not vary for histological subtypes.

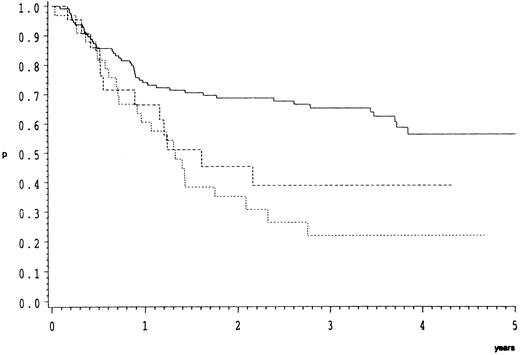

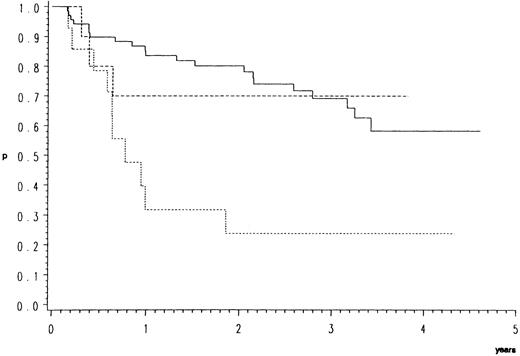

Survival.As compared to CB, the response data imply an inferior prognosis for B-ALC and even a worse one for B-IB lymphoma. This is indeed the case as illustrated by the overall (Fig 1) and relapse free survival probabilities (Fig 2). In the direct pairwise comparison, prognosis in CB lymphoma differs significantly from B-IB in overall (P = .0002) and relapse-free survival (P = .003) and slightly so from B-ALC in overall (P = .046) but not in relapse-free survival. Even if not significantly, overall and even more so relapse-free survival (P = .066) were better in B-ALC than B-IB.

Overall survival of 182 patients with high-grade malignant B-cell lymphomas treated by the COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 regimen (BMFT trial5 ); (patients at risk at 1/2/3/4 years). Lymphoma subtypes (Kiel classification): ———, centroblastic n = 127 (87/69/52/19); - - - -, B-anaplastic large cell (CD30+) n = 22 (13/8/4/1); ⋅⋅⋅⋅, B-immunoblastic n = 33 (20/8/5/4) P = .0005.

Overall survival of 182 patients with high-grade malignant B-cell lymphomas treated by the COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 regimen (BMFT trial5 ); (patients at risk at 1/2/3/4 years). Lymphoma subtypes (Kiel classification): ———, centroblastic n = 127 (87/69/52/19); - - - -, B-anaplastic large cell (CD30+) n = 22 (13/8/4/1); ⋅⋅⋅⋅, B-immunoblastic n = 33 (20/8/5/4) P = .0005.

Relapse-free survival of 96 patients with high-grade malignant B-cell lymphomas having achieved complete response by the COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 regimen (BMFT trial5 ); (patients at risk at 1/2/3/4 years). Lymphoma entities (Kiel classification): ———, centroblastic n = 72 (53/40/25/6); - - - -, B-anaplastic large cell (CD30+) n = 10 (7/5/3/3); ⋅⋅⋅⋅, B-immunoblastic n = 14 (4/3/3/2) P = .0025.

Relapse-free survival of 96 patients with high-grade malignant B-cell lymphomas having achieved complete response by the COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 regimen (BMFT trial5 ); (patients at risk at 1/2/3/4 years). Lymphoma entities (Kiel classification): ———, centroblastic n = 72 (53/40/25/6); - - - -, B-anaplastic large cell (CD30+) n = 10 (7/5/3/3); ⋅⋅⋅⋅, B-immunoblastic n = 14 (4/3/3/2) P = .0025.

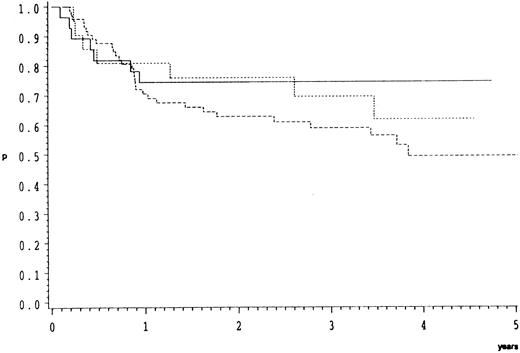

Morphological subgroups of CB lymphoma were analyzed separately. As depicted in Fig 3 overall survival did not differ significantly (P = .48) between these.

Overall survival of 123 patients with CB lymphoma treated by the COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 regimen (BMFT trial5 ) (patients at risk at 1/2/3/4 years). CB lymphoma subgroups (Kiel classification): ———, multilobated n = 28 (20/17/14/5); - - - -, polymorphic n = 74 (47/37/26/11); ⋅⋅⋅⋅, monomorphic n = 21 (16/12/10/2); P = .48.

Overall survival of 123 patients with CB lymphoma treated by the COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 regimen (BMFT trial5 ) (patients at risk at 1/2/3/4 years). CB lymphoma subgroups (Kiel classification): ———, multilobated n = 28 (20/17/14/5); - - - -, polymorphic n = 74 (47/37/26/11); ⋅⋅⋅⋅, monomorphic n = 21 (16/12/10/2); P = .48.

Centrocytoid and simultaneous secondary centroblastic lymphoma.The 18 cases of centrocytoid (cCB) and the 19 cases of simultaneous secondary CB (ssCB) identified in the treatment trial were evaluated separately and compared to the common CB cases (n = 127). Among the initial parameters, differences include a slightly higher median age (61 and 60 years in cCB and ssCB, respectively), and lower rate of LDH elevation (39% and 47%, respectively). Noteworthy are the high incidence of bone marrow infiltration (28%) in cCB and of gastrointestinal involvement in ssCB (42 %). Responses to chemotherapy (61% and 53%, respectively) were quite similar to the whole group of true CB (57%) and overall survival of cCB and ssCB as compared with the three subtypes of common CB did not differ significantly (P = .46).

Multivariate analysis of prognostic risk.To assess possible correlations of histological suptype to established prognostic risk factors, multivariate analyses were performed of the Kiel classification in combination with the parameters of the International Index (age >60 years, Karnofsky index ≤70 %, Ann Arbor stage III/IV, serum LDH > normal, number of extranodal manifestations ≥2).12 The results are given in Table 3. For overall survival the performance status is predominantly relevant, followed by B-IB histology and LDH while B-ALC histology looses impact. The relative risk associated with B-IB as compared to CB is almost identical to that correlated with LDH. Relapse-free survival is significantly and equally influenced by age and even more so by B-IB histology (relative risks of 1:2.70 and 1:3.00, respectively). In addition to individual factors, the histological entities were analyzed in comparison to risk groups. In view of the limited case numbers in B-IB and B-ALC, a meaningful evaluation was approached by forming risk categories from the combination of the low and low-intermediate (low-risk category) and the high-intermediate and high-risk groups (high-risk category) of the International Index. As shown in Table 3, overall and relapse-free survival is predominantly determined by these risk categories but the distinction of CB and B-IB histology retains significance.

These results show that the CB and B-IB histological subtype as defined by the Kiel classification constitutes an independent significant prognostic factor for overall survival and relapse-free survival. This remains valid even if the major initial adverse risk factors or risk groupings are taken into account.

DISCUSSION

A comprehensive experience in the management of clinically aggressive NHLs has been accumulated internationally and a multitude of treatment protocols have been developed and successfully applied.13 The direct comparison of therapy trials, though, was so far impeded by the incongruence of the histological classification systems applied of which the Working Formulation14 and Kiel classification1 2 have been most broadly used during the last years.

In randomized comparisons of different regimens significant survival advantages have only rarely been identified for a particular protocol15,16 or not at all.17-20 Moderate increases of standard chemotherapy dosages did not yet improve response or survival,17,18 but with the support of hematopoetic growth factors, relevant escalations of dosage, and dose intensity have become feasable.21-23 Additionally, selected patients were safely treated by myeloablative high-dose therapy followed by progenitor cell rescue but results presented to date yet remain controversial.24-26 Thus, a broad spectrum of therapeutic options is available. For the individual patient the choice of treatment depends on an initial estimation of prognostic risk for which numerous relevant parameters were identified.27 Only a minority, though, eg, β2 -microglobulin and the factors of the International Index, have already been confirmed by long-term observations in larger series and are readily available in routine clinical settings.

In this context, the possible prognostic relevance of histology has gained new attention which was sparked by the recently reported REAL classification.3,4 Among other aspects this proposal is remarkable for being the first to present a consensus supported by an international panel of hematopathologists as emphasized by subsequent commentaries28,29 in the vivid discussion about its crucial features and clinical applications.28-33 In the meantime, reassessment of diagnoses according to the REAL classification in larger clinical trials originally categorized by the Working Formulation have been reported34-36 illustrating the usefullness of the new proposal in clinical practice.

The present study addressed the question whether or not the combination of CB, B-IB, and B-ALC lymphomas distinguished by the Kiel classification1,2 in one category of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as defined by the REAL classification3 is clinically justified. Therefore, the relevant subgroup of patients treated in the prospective randomized COP-BLAM/IMVP-16 study5 were submitted to a detailed analysis. From the start of the trial, diagnoses were based on the Kiel classification, which was thereby approached in a prospective manner.

After completion of the study biopsy specimens were further investigated (M.T. and H.G.) and subjected to final review by the reference pathologist (K.L.). It should be emphasized that to establish the diagnosis of CB, B-IB, and B-ALC lymphomas rather subtle morphological and cytological details of NHL are readily distinguished in good quality Giemsa-stained routine specimens.1 Overcoming the difficulties in distiguishing the three main types of large B-cell lymphomas histologically is a matter of training and of high quality histological techniques. The diagnostic slides reviewed in this study were all derived from paraffin sections. However, it was generally not possible to evaluate the original slides from the various participating centers. Instead, new thin sections were always prepared for optimal Giemsa staining. This procedure can then be and was in this analysis supplemented by ancillary techniques such as immunohistochemistry and molecular genetical methods, which offer a promising approach to further investigations of the biology of these distinct lymphoma subtypes.

The histological diagnoses were then correlated with the clinical characteristics of the patients (Table 1). Observed differences never reached the border of statistical significance although the limited case series in B-IB and B-ALC preclude definite results in these comparisons. However, it appeared that B-IB patients tended to be males, presenting in a poorer performance status (Karnofsky index), with more advanced (bulky tumors, stage III/IV) and active disease (serum-LDH), with a higher incidence of skin or skeleton infiltration but less bone marrow involvement as compared to CB lymphomas. With the exception of male predominance, this pattern is also valid for B-ALC lymphomas although less pronounced. Similarily, the dynamic of response achievement slows down and complete response rates decline from CB (57%) to B-ALC (45%) to B-IB (42%) (P = .26) (Table 2). The stability of remissions achieved is identical in CB and B-ALC lymphomas but significantly worse in B-IB (P = .010). These response parameters could not be related to major variations of study protocol adherence (number of chemotherapy cycles, dose intensity, adjuvant radiotherapy).

The criteria of disease presentation at the time of diagnosis and the response to standard therapy imply a relevantly better long-term prognosis for CB as compared to B-ALC or even B-IB. This was indeed observed in univariate comparisons as also illustrated in Fig 1 by overall survival and in Fig 2 by relapse-free survival. In B-ALC poor response to induction therapy and an aggressive initial course of disease result in a worse survival than in CB (P = .046) while remissions achieved tend to be equally stable. On the other hand, the distinction of morphological subgroups of CB lymphoma did not influence overall survival (Fig 3).

The separately evaluated small series of centrocytoid CB that is now considered a variant of mantle cell lymphoma was indeed associated with a relatively high incidence of bone marrow infiltration–as would be expected for the low grade lymphoma. Similarily, simultaneous secondary CB had a high rate of gastrointestinal involvement not uncommon in centroblastic-centrocytic lymphoma from which it probably evolved. The relatively favorable overall survival for these two entities is noteworthy but clearly requires confirmation by larger case series.

To clarify whether the prognostic differences between CB, B-IB, and B-ALC might be explained by established general risk features, multivariate analyses were performed including the prognostic risk factors identified by the International Index (age, performance status, stage, serum-LDH, number of extranodal sites)12 or the combined risk categories defined by these factors (Table 3). In multivariate comparisons B-ALC looses independent influence on prognosis although the case series is probably too small to draw firmly supported conclusions. Although the performance status (Karnofsky index) is of predominant importance, the impact of CB or B-IB subtype on overall survival is also significant and equals that of the serum-LDH. Relapse-free survival is strongly influenced by advanced age but the distinction of CB and B-IB does retain relevance. Similar results are obtained in the evaluation of these lymphomas in the context with low and high-risk groupings. These histological subtypes thus constitute independent prognostic factors.

The morphological distinction between CB, B-IB, and B-ALC lymphomas can be shown to correspond to characteristic patterns of initial lymphoma manifestations and clinical behavior under standardized treatment conditions. The poor prognosis of immunoblastic as opposed to centroblastic lymphoma is indirectly supported already by the Working formulation,14 where based on clinical experiences, corresponding lymphomas were also assigned to different groupings.

The present analysis shows significant prognostic differences between centroblastic and B-immunoblastic lymphomas, and to B-anaplastic large cell (CD30+) in a modified form. These observations are suggestive of inherent biological, possibly genetically determined features of these lymphoma entities. The subsumption of these subtypes into one common category of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas as proposed by the REAL classification3 will miss the prognostic heterogeneity within this group and therefore will fail to identify patients who may require other than standard (eg, possibly early intensified) treatment. The morphological distinction of the CB, B-IB, and B-ALC entities in the Kiel classification1 2 of NHL bears significant prognostic relevance worthy of consideration in future experimental and clinical research strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We expressedly wish to thank the further contributors to the study (in alphabetical order, all in Germany): J. Beier, Bochum; V. Diehl, Cologne; W. Dornoff, Trier; W. Enne, Munich; W. Gassmann, Kiel; R. Haas, Heidelberg; A.R. Hanauske, Munich; J. Heise, Krefeld; R. Kuse, Hamburg; E. Lengfelder, Mannheim; M. Pfreundschuh, Homburg; C. Schadeck-Gressel, Duisburg; G. Schlimock, Augsburg; W. Schneider, Düsseldorf; C. Schöber, Hannover; H.J. Staiger, Karlsruhe; E. Terhardt, Duisburg; T. Wagner, Lübeck; W. Weber, Trier; M.G. Willems, Cologne; M. Wüllenweber, Neuss.

Supported by a grant from the German Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technologie (BMFT).

Address reprint requests to Marianne Engelhard, MD, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology, Universitätsklinikum Essen, Hufelandstraβe 55, D-45147 Essen, Germany.