Abstract

Dendritic cells (DC) are potent antigen-presenting cells (APC) with the capacity to stimulate a primary T lymphocyte immune response and are therefore of interest for potential immunotherapeutic applications. Freshly isolated DC or DC precursors may be preferable for studies of antigen uptake and the potential control of APC costimulator activity. In this report, we report that the monoclonal antibody CMRF-44 can be used to detect early DC differentiation. The majority of DC circulating in blood do not express any known DC lineage specific markers, but can be identified by CMRF-44 labeling after a brief period of in vitro culture. The sequential acquisition of DC activation antigens allows the identification of two stages of DC maturation/activation. Cytokines, especially granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF )α, enhance both phases of this process, whereas CD40-ligand trimer preferentially enhances the final DC maturation to a fully mature, activated phenotype. DC positively selected using CMRF-44 possess potent allostimulatory activity and are efficient at the uptake, processing, and presentation of soluble antigens for both primary and secondary immune responses. CMRF-44+ DC are also more potent than other APC types at restimulation of a chronic myeloid leukemia peptide specific T-cell clone. The use of a purified population of freshly isolated DC may be advantageous in attempts to initiate, maintain, and direct immune responses for immunotherapeutic applications.

DENDRITIC CELLS (DC) are specialist antigen-presenting cells (APC), which play a crucial role in the initiation of a primary immune response. The isolation of DC or their precursors from blood has been difficult in view of their scarcity and the absence of well-established DC lineage markers.1,2 Alternative means of obtaining DC have been explored and cells with DC-like characteristics have been generated by extended culture of blood, bone marrow, or cord blood precursor cells in the presence of cytokines, typically granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF )α or interleukin (IL)-4,3,4,5 resulting in expansion of cell numbers and differentiation of several lineages, including DC. While many of the cells generated in this manner share functional attributes of DC, these methods do not produce homogeneous populations and there are subtle phenotypic differences between these cells and DC isolated directly from blood or tonsil.6,7 Attempts have been made recently to clarify the leukocyte populations present and the conditions governing DC ontogeny,8 although how closely in vitro DC differentiation parallels in vivo events is less clear. It is possible that exposure to self or foreign antigen and the high cytokine levels during extended in vitro culture may result in aberrant DC function.

Immature DC have high antigen processing ability that is diminished on maturation.9 Therefore, freshly isolated blood DC may be more suitable to the development of immunotherapeutic regimens, as well as providing a suitable DC population for the study of antigen loading mechanisms and regulation of costimulator activity. However, isolation of immature DC from blood by methods involving negative selection do not yield a pure DC population. While expression of HLA class II can be used to identify DC precursors, this approach is not suitable for functional studies because of the effects of anti-class II antibodies on DC function.

The recent development of the CMRF-4410 and HB15a (CD83)6 monoclonal antibodies (MoAb), which recognize DC activation antigens, allows positive selection of DC populations from human blood for experimental and possibly clinical immunotherapeutic protocols. We report here that the CMRF-44 antigen is expressed early in the course of DC differentiation from a circulating precursor, and that by observing the differential expression of this antigen and CD83, intermediate stages of early DC differentiation can be identified and some of the factors that influence this process clarified. We were then able to test the hypothesis that the rapid upregulation of the CMRF-44 antigen may be exploited to prepare highly purified DC populations, which retain significant antigen processing activity. We show CMRF-44 purified DC have potent antigen presenting activity after pulsing with synthetic peptide and, therefore, hold promise for use in human immunotherapy protocols. As evidence accumulates that DC not only initiate the immune response, but may also influence the outcome of the T-lymphocyte response,11 the ability to purify and study DC at different states of differentiation/activation may be useful in manipulating APC function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monoclonal antibodies and immunolabeling.The MoAbs CMRF-15 (antierythrocyte α sialoglycoprotein, IgM), CMRF-31 (anti-CD14, IgG2a), CMRF-44 (IgM), and biotinylated CMRF-44 were produced in this laboratory. HB15a (anti-CD83, IgG2b) was a gift from Dr T. Tedder, Duke University, Durham, NC. The negative controls X63 (IgG1), Sal4 (IgG2b), Sal5 (IgG2a) were a gift from Professor H. Zola (Flinders Medical Center, Adelaide, Australia). Bu63 (CD86, IgG1) was a gift from Dr D. Hardie (University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK). HuNK-2 (anti-CD16, IgG2a) was a gift from Professor I. McKenzie (Austin Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia). WM54 (anti-CD33, IgG1) and WM15 (anti-CD13, IgG1) were a gift from Dr K. Bradstock (Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia). G28-5 (anti-CD40, IgG1), OKT3 (anti-CD3, IgG2a), HNK-1 (anti-CD57, IgM), and OKM1 (anti-CD11b, IgG1) were produced from hybridomas obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD). L307 (CD80, IgG1) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies to CD14 (leuM3, IgG2b), CD19 (leuM12, IgG1), CD34 (anti-HPCA–2, IgG1), HLA-DR (L243, IgG2a), and PerCP-avidin were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Mountain View, CA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated sheep antimouse immunoglobulin (FITC-SAM) was purchased from Silenus (Hawthorn, Australia).

Labeling was performed by standard techniques. Briefly, cells were incubated with saturating concentrations of primary antibody for 30 minutes at 4°C, washed twice, incubated with FITC-SAM for 30 minutes at 4°C, washed twice, blocked with 10% mouse serum for 5 minutes and then incubated with PE-conjugated or biotinylated second antibody. For biotinylated antibodies, a further washing step was followed by incubation with PE or PerCP-avidin for 30 minutes and a final washing before analysis or sorting on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) Vantage (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Samples that could not be analyzed immediately were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C.

Cell preparation.Blood was obtained from volunteer donors with appropriate informed consent according to Ethical Committee guidelines. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were prepared by isolation over sterile Ficoll/Hypaque (d = 1.077 g/mL; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) gradients. T lymphocytes for functional assays were prepared from PBMC by rosetting with neuraminidase-treated sheep erythrocytes, followed by Ficoll/Hypaque separation and erythrocyte lysis with distilled water.

Dendritic cell preparation.(1) For experiments involving phenotypic analysis of freshly isolated and cultured DC, freshly isolated PBMC were depleted of T lymphocytes as above and then labeled with a mix of CD3, CD11b, CD14, CD16, and CD19 MoAb. After incubation with goat antimouse Ig-coated magnetic microspheres (Miltenyi Biotech, Germany), labeled cells were removed by magnetic immunodepletion and the MoAb negative cells were then labeled with FITC-SAM and further purified by sorting using a FACS Vantage flow cytometer, if required. Two or three color immunofluorescent labeling was then used to identify DC on the basis of HLA-DR and/or CMRF-44 staining.

(2) For functional studies, DC were purified by positive selection using CMRF-44 labeling. Briefly, PB non-T cells were isolated as above and then cultured at 2 × 107/mL for 12 to 15 hours. Low density cells were then isolated by separation over a Nycodenz (Nycomed Pharma, Norway) gradient (d = 1.068 g/cm3 ) as previously described.12 Cells were washed three times and labeled sequentially with CMRF-44, FITC-SAM, and CD14-PE. CMRF-44++, CD14− cells were sorted to high purity and used for functional studies.

Cell lines.The HLA-DR1–restricted CD4 T-lymphocyte line (NG-1), which recognizes a chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)-specific peptide derived from the b3a2, bcr-abl fusion protein arising as a consequence of the 9:22 translocation was generated in this laboratory.13 NG-1 was maintained by periodic restimulation with b3a2 peptide plus autologous MNC feeder cells and was rested before use in antigen presentation experiments.

Medium and cytokines.Cell culture medium used unless otherwise stated was RPMI-1640 supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Life Technologies, Auckland, New Zealand). AIM-V medium (Life Technologies) was used for experiments performed in serum-free conditions. In some experiments, base media was supplemented with one of the following cytokines: IL-2 (100 U/mL), TNFα (20 ng/mL; both from Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland), IL-3 (20 ng/mL; R & D Systems, Oxford, UK), IFNγ (500 U/mL; Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany), IL-4 (25 ng/mL; Sigma, St Louis, MO), or GM-CSF (500 U/mL; Sandoz, Basel, Switzerland). Murine CD40-ligand trimer (mCD40-LT), which is capable of binding human CD40 (gift from Dr M. Widmer, Immunex, Seattle, WA) was used at 10 μg/mL.

Functional assays.Allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR): 105 T lymphocytes were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in 96-well plates with triplicate graduated numbers of sorted APC subsets obtained from a single allogeneic donor. Wells were pulsed for 12 hours with 0.5 μCi tritiated thymidine (Amersham International, Arlington Heights, IL) immediately before harvest at 5 days. Cells were harvested onto filter paper and thymidine incorporation was measured with a liquid scintillation counter. Data are expressed as mean counts per minute (CPM) of triplicate wells ± standard deviation (SD). Control wells containing T cells or APC alone incorporated <500 cpm of tritiated thymidine in all experiments.

Soluble protein or peptide presentation assays and autologous MLR: These assays were performed following previously published methods14 15 with minor modifications. Briefly, 105 T lymphocytes were cultured with 5,000 autologous APC without antigen or with 10 ng/mL keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH; Sigma) or 1 μg/mL tetanus toxoid (Commonwealth Serum Laboratory, Melbourne, Australia) in 96-well plates. Each well was harvested after 8 days following a 12-hour pulse with 0.5 μCi tritiated thymidine. Results are expressed as mean CPM of triplicate wells ± SD. For assays of peptide presentation, 2.5 × 104 NG-1 responder T lymphocytes were cultured with graduated doses of peptide pulsed (10 μg/mL) APC obtained from HLA-DRB1*0101 donors, and thymidine incorporation was assayed after 3 days.

RESULTS

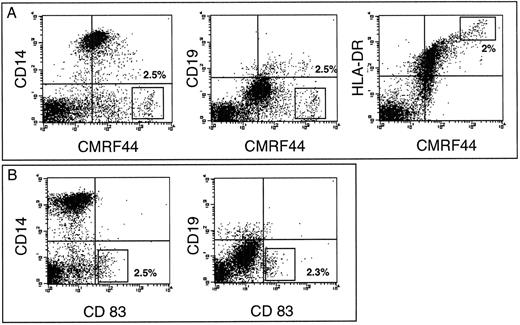

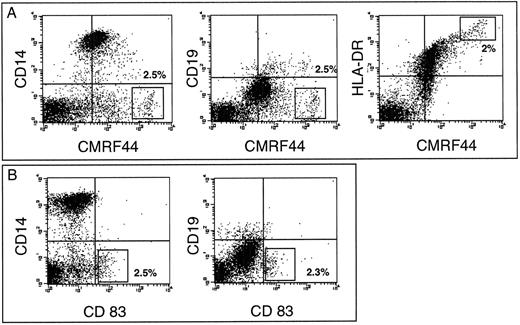

A CMRF-44 bright, putative DC population can be identified after in vitro culture of freshly isolated PBMC.We have previously established that CMRF-44 labels B lymphocytes, monocytes, and DC, but does not stain other blood cells.10 We now extend this data to show that a strongly CMRF- 44 positive, putative DC population is discriminated from CD19+ B lymphocytes and CD14+ monocytes by the intensity of CMRF-44 staining. Enumeration of the CMRF-44++ (bright) population after 24 hours of culture estimated the DC percentage at 0.2% to 1% of PBMC (n = 7). This percentage increased to 2% to 3% (n = 3) at 48 hours (Fig 1A). The CMRF 44++ (bright) population also express higher levels of HLA-DR than other cultured PBMC (Fig 1A). The relatively DC-specific CD83 antigen6 is recognized on a similarly sized population by HB15a labeling (Fig 1B). Ongoing maturation of precursors, further DC division, or preferential survival of DC probably accounts for the increase of CMRF-44 bright cells. The relative contribution and kinetics of these processes varied between individuals and may account for the variation in DC yields seen between individual donors. The CMRF-44 bright (non-B lymphocyte/monocyte population) was also generated in commercially prepared, (endotoxin-free) serum-free media (AIM V) (n = 5). Again, considerable interindividual variation in DC numbers was observed between donors, making it unlikely that this variability is solely due to idiosyncratic reactions to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or similar substances that may be present in serum.

CMRF-44 labels cultured peripheral blood DC. T-lymphocyte depleted PBMC were cultured for 48 hours and labeled with the MoAb indicated. The quadrants were placed according to isotype matched control staining performed at each time point. The percentage of cells with (A) the CMRF-44 bright or (B) HB15a+ phenotype (shown in rectangle) was 2% to 2.5% in this individual. Antibody labeling intensity is displayed across 4 decades of log fluorescence in all figures. Results are from one of three similar experiments.

CMRF-44 labels cultured peripheral blood DC. T-lymphocyte depleted PBMC were cultured for 48 hours and labeled with the MoAb indicated. The quadrants were placed according to isotype matched control staining performed at each time point. The percentage of cells with (A) the CMRF-44 bright or (B) HB15a+ phenotype (shown in rectangle) was 2% to 2.5% in this individual. Antibody labeling intensity is displayed across 4 decades of log fluorescence in all figures. Results are from one of three similar experiments.

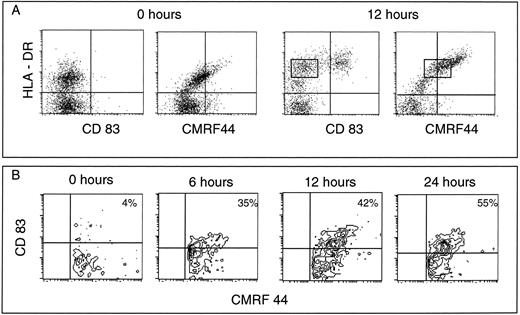

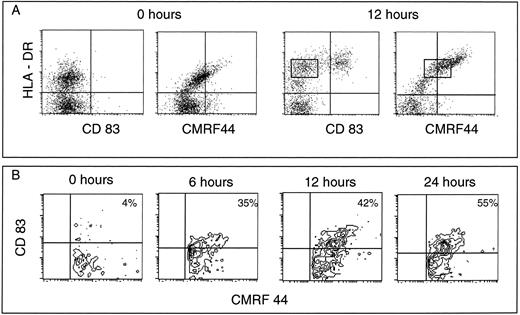

Small numbers of CMRF-44 positive DC are present in freshly isolated PBMC and DC rapidly upregulate CMRF-44 during in vitro culture.To examine the upregulation of the CMRF-44 and CD83 antigens on the putative blood DC precursor population, we prepared PBMC and depleted mature leukocyte populations as described in the Materials and Methods section. The resultant lineage negative population (typically < 4% of freshly isolated PBMC) included 30% to 80% HLA-DR positive cells. CMRF-44 labeled the most strongly HLA-DR staining cells before in vitro culture and subsequently labeled 50% to 80% of the HLA-DR positive cells after a short period of culture in serum containing medium (Fig 2A). The CD83 antigen was not expressed on these freshly isolated DC precursor populations initially, but was detected after culture on the HLA-DR bright cells (Fig 2A). The expression of the CMRF-44 antigen preceded that of the CD83 antigen (Fig 2B) at early time points, although beyond 24 hours, the percentage of cells labeled by CMRF-44 and HB15a was essentially the same (Fig 1A and B).

CMRF-44 positive blood DC can be detected before culture. (A) Mature lineage positive mononuclear cells were removed by magnetic immunodepletion. The resulting lineage negative cells were labeled before (0 hours) and after 12 hours culture. A lineage negative, CMRF-44 positive subpopulation is noted. The differential expression of the activation antigens recognized by CMRF-44, HB15a (CD83), and anti-HLA-DR antibodies allow the identification of distinct stages of early DC development (see text). The rectangle indicates the CMRF44+/CD83− stage of DC differentiation . (B) Time course labeling of cultured lineage negative cells gated on CMRF-44 positive cells showing the differential expression of the CMRF-44 and CD83 antigens. No CD83+/CMRF-44− cells were detected at any time point. Quadrants are placed according to isotype-matched negative controls such that <95% of events are excluded from the right-hand quadrants. Results are from one of three similar experiments.

CMRF-44 positive blood DC can be detected before culture. (A) Mature lineage positive mononuclear cells were removed by magnetic immunodepletion. The resulting lineage negative cells were labeled before (0 hours) and after 12 hours culture. A lineage negative, CMRF-44 positive subpopulation is noted. The differential expression of the activation antigens recognized by CMRF-44, HB15a (CD83), and anti-HLA-DR antibodies allow the identification of distinct stages of early DC development (see text). The rectangle indicates the CMRF44+/CD83− stage of DC differentiation . (B) Time course labeling of cultured lineage negative cells gated on CMRF-44 positive cells showing the differential expression of the CMRF-44 and CD83 antigens. No CD83+/CMRF-44− cells were detected at any time point. Quadrants are placed according to isotype-matched negative controls such that <95% of events are excluded from the right-hand quadrants. Results are from one of three similar experiments.

Three distinct phenotypic states of activation/maturation can be clearly identified in conjunction with changes in cell size. Progression from an HLA-DR positive, CMRF-44−/+ CD83- DC precursor population through an HLA-DR positive, CMRF-44+ CD83−/+ intermediate state to an HLA-DR bright CD83+ and CMRF-44++ mature DC was observed (Fig 2A). The HLA-DR+ lineage mix negative population possess the forward and side scatter characteristics of lymphocytes, the intermediate stage of CMRF-44+ cells fall between the lymphoid and monocytoid gates, and the CMRF-44++ cells are found in the monocyte gate (data not shown). The phenotype of these populations was analyzed and is summarized in Table 1 (data obtained from a minimum of three experiments per antigen). Of note, the CD40, CD80, and CD86 antigens increase in density on DC as they progress through these steps.

In the majority of experiments, an almost linear relationship between HLA-DR and CMRF-44 labeling was seen. It should be noted that the CMRF-44 antigen has been characterized as a glycolipid and distinguished from the currently known HLA-DR products11 and that CMRF-44 does not label HLA-DQ or DR-transfected L cells, or the small number of CD34 positive cells (known to be DR and DP positive) also present in the lineage negative, HLA-DR positive population.

The short-term development of DC can be augmented with additional cytokines.When PBMC preparations are cultured (as above), DC development may be supported by cytokines or other products released by mature cells, as well as serum additives in the culture media. The effect of cytokine supplementation on early DC differentiation was examined in the absence of mature leukocytes after freshly isolated, lineage mix negative cells (prepared as described earlier) had been cultured for 40 hours in the presence of additional cytokines. In contrast to the results seen in above, there was less DC differentiation and lower DC viability in serum-free conditions indicating that these lineage mix negative cells alone are either unable or not sufficiently stimulated to produce cytokines needed for this process. The addition of 10% FCS had a greater effect than any individual cytokine or TNFα, GM-CSF, and IL-4 combined (not shown).

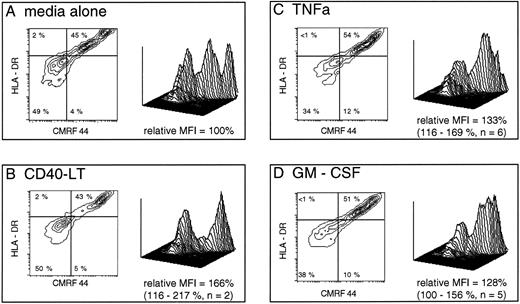

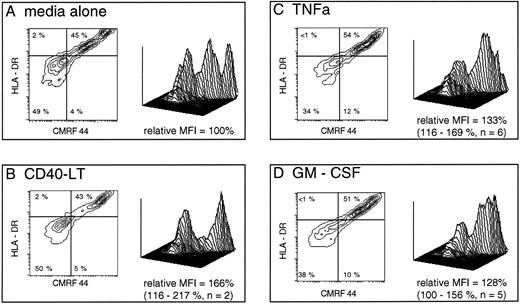

In the presence of 10% FCS, GM-CSF, and TNFα, both increased cell viability and consistently enhanced early maturation from early and intermediate DC precursors, as judged by both absolute CMRF-44 positive cell numbers and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CMRF-44 labeling (Fig 3). The increase in CMRF-44 expression induced by additional cytokines (relative to that induced in RPMI/10% FCS alone) was 135% of control with TNFα (95% confidence interval [CI], 110% to 155%) and 128% of control with GM-CSF (95% CI, 98% to 173%). IL-3 and IFNγ had a similar, but less marked effect on increasing the number of CMRF-44 and CD83 positive cells in some experiments. The presence of CD40-LT did not enhance the maturation from early DC precursors, but did increase the MFI of HLA-DR, CMRF-44 (Fig 3), and HB15a labeling (not shown) on the more mature DC.

Short-term development of CMRF-44++ DC in culture is augmented by additional signals. Freshly isolated PB lineage marker negative cells were prepared (as described in Materials and Methods) and were cultured for 40 hours in media alone or with additional cytokines as shown. The plots are gated on live cells (as assessed by forward and 90° light scatter characteristics) which expressed HLA-DR. A total of 10,000 events were collected in each case using identical gating criteria. The relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CMRF-44 labeling in each case was calculated using the formula: MFI CMRF-44 (media + cytokine) - MFI (control Ab)/MFI CMRF-44 (media alone) - MFI (control Ab) and expressed as a percentage. Additional GM-CSF or TNFα both increased the number of viable cells by up to 20% compared with media alone. Quadrants are placed as dictated by isotype matched control antibody (x axis) and at the level of class II expressed on these cells before culture (y axis). Percentages of cells falling into each quadrant are shown. The three-dimensional plots depict the same data and allows a comparison of the cytokine effect at each stage of DC development.

Short-term development of CMRF-44++ DC in culture is augmented by additional signals. Freshly isolated PB lineage marker negative cells were prepared (as described in Materials and Methods) and were cultured for 40 hours in media alone or with additional cytokines as shown. The plots are gated on live cells (as assessed by forward and 90° light scatter characteristics) which expressed HLA-DR. A total of 10,000 events were collected in each case using identical gating criteria. The relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CMRF-44 labeling in each case was calculated using the formula: MFI CMRF-44 (media + cytokine) - MFI (control Ab)/MFI CMRF-44 (media alone) - MFI (control Ab) and expressed as a percentage. Additional GM-CSF or TNFα both increased the number of viable cells by up to 20% compared with media alone. Quadrants are placed as dictated by isotype matched control antibody (x axis) and at the level of class II expressed on these cells before culture (y axis). Percentages of cells falling into each quadrant are shown. The three-dimensional plots depict the same data and allows a comparison of the cytokine effect at each stage of DC development.

In all experiments, a variably sized population of HLA-DR positive cells was present, which did not acquire the CMRF-44 positive phenotype of DC during the culture period (Figs 2 and 3). There was no evidence that these cells could differentiate into CD14 positive monocytes under these conditions (not shown). The phenotypic data (Table 1) suggests that the HLA-DR positive, non-DC, population comprises a mixture of CD34+ precursors, other immature myeloid cells (CD13 and/or CD33 positive), activated T lymphocytes (CD3 low, CD4+,CD25+), and possibly other cell types. A variable percentage of HLA-DR negative cells are present in lineage negative PBMC preparations, but they did not label with either CMRF-44 or HB15a under any culture conditions, although IFNγ induced HLA-DR in a small percentage of these cells.

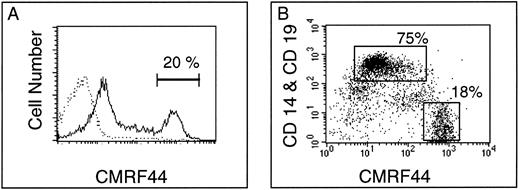

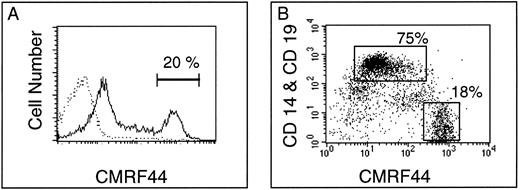

CMRF-44 provides a convenient method for blood DC purification. (A) After in vitro culture of peripheral blood ER negative cells, density gradient separation typically enriched CMRF-44 bright DC population from <1% to 15% to 25%. (B) Double labeling with CD14 to identify the coenriched low density monocytes (70% to 80% of low density cells) allows clear separation of the CMRF-44 bright population (15% to 20% of low density cells), which can then be sorted to high purity. In this example, the CD19-PE has been added to show the small (1% to 2%) population of B lymphocytes also present. Typical sort regions are shown.

CMRF-44 provides a convenient method for blood DC purification. (A) After in vitro culture of peripheral blood ER negative cells, density gradient separation typically enriched CMRF-44 bright DC population from <1% to 15% to 25%. (B) Double labeling with CD14 to identify the coenriched low density monocytes (70% to 80% of low density cells) allows clear separation of the CMRF-44 bright population (15% to 20% of low density cells), which can then be sorted to high purity. In this example, the CD19-PE has been added to show the small (1% to 2%) population of B lymphocytes also present. Typical sort regions are shown.

The rapid induction of CMRF-44 can be exploited to simplify the purification of DC.Previous experiments12 have shown that during short-term (12 to 16 hours) in vitro culture of T-lymphocyte–depleted PBMC, DC reduce their buoyant density. Isolation of low density cells over a Nycodenz gradient enriched the CMRF-44 bright cells from <1% of the starting population to 15% to 25% of the low density fraction (Fig 4A). The expression of CMRF-44 on monocytes varies between individuals, therefore double labeling with CD14 to identify the coenriched low density monocytes was used to ensure that the CMRF-44 bright, CD14 negative population was sorted to high purity. Typical two color labeling and sort regions for DC (CMRF-44++, CD14−) and copurified, low density monocytes (CMRF-44−/+, CD14+) are shown (Fig 4B) as representative of over 25 experiments. The viability of the sorted cells was typically >85%, reducing to ≈ 50% after a further 24-hour culture, as expected when the sorted DC are cultured in isolation. Morphologically, the sorted DC show some heterogeneity, probably as a result of differential maturation status, but the majority are medium/large cells with a characteristic irregular nucleus. The phenotype of the sorted cells is shown in Table 1. The CMRF-44 antibody does not affect the allostimulatory potential of DC,11 but as yet, no further functional data on the antigen is available.

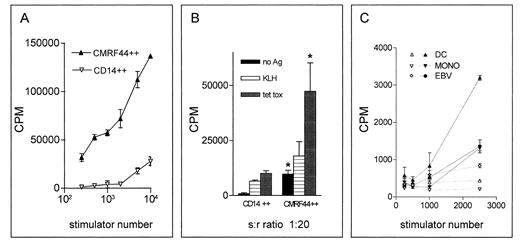

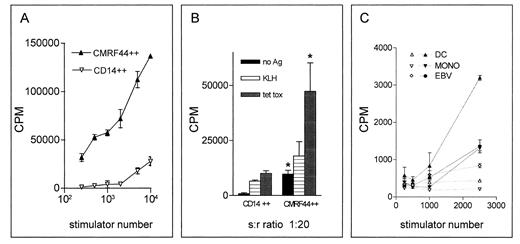

CMRF-44 positive cells have potent antigen presenting capacity. CMRF-44 bright, CD14 negative DC were compared with CD14 bright, CMRF-44 dim monocytes in their ability to (A) stimulate an allogeneic MLR, (B) process and present primary and recall antigens to autologous T cells (* represents significant (P < .05 by student's t test) difference between DC and monocytes), (C) or present peptide antigen to an established CML fusion protein bc-abl specific T-cell line (open symbols, no antigen; closed symbols, b3a2 peptide). In all cases, CMRF-44 bright DC show greater stimulatory activity than other APC types, emphasizing the potential of these cells for immunotherapeutic applications.

CMRF-44 positive cells have potent antigen presenting capacity. CMRF-44 bright, CD14 negative DC were compared with CD14 bright, CMRF-44 dim monocytes in their ability to (A) stimulate an allogeneic MLR, (B) process and present primary and recall antigens to autologous T cells (* represents significant (P < .05 by student's t test) difference between DC and monocytes), (C) or present peptide antigen to an established CML fusion protein bc-abl specific T-cell line (open symbols, no antigen; closed symbols, b3a2 peptide). In all cases, CMRF-44 bright DC show greater stimulatory activity than other APC types, emphasizing the potential of these cells for immunotherapeutic applications.

Using this method 0.5 to 2 × 105 DC can be obtained from 100 mL blood. The technique can be readily scaled up to handle larger cell numbers, such as an apheresis product, from which sufficient DC (1 to 10 × 106) for clinical applications may be obtained.

Low density, CMRF-44 positively selected cells possess the functional attributes of DC.Sorted CMRF-44 bright DC were potent stimulators of the allogeneic MLR with as few as 200 DC showing significant activity. The purified DC were 10 to 100 times more stimulatory than the (CMRF-44−/+, CD14+) monocytes, which were also isolated from the Nycodenz gradient (Fig 5A, representative of five experiments).

A critical observation was that the CMRF-44 bright cells retain the ability to process and present antigen to autologous T lymphocytes after a 12-hour period of in vitro culture. When CMRF-44 bright cells were cultured with autologous T lymphocytes, a substantial background autologous MLR response was generated. Pulsing the cells with KLH resulted in additional T-lymphocyte proliferation, establishing that these CMRF-44 bright cells can take up and process antigen effectively and present the resulting KLH peptides to generate a primary T lymphocyte response (Fig 5B, representative of three experiments). A similar specific and more substantial secondary T-lymphocyte response to tetanus toxoid was also seen (Fig 5B). It is noteworthy that high DC stimulator ratios generated increasing nonspecific responses, suggesting lower DC:T lymphocyte ratios are better for in vitro initiation of a specific response.

Finally, CMRF-44 bright cells are also capable of presenting a synthetic CML bcr-abl fusion protein antigenic peptide to a T-cell line specific for this peptide (Fig 5C, representative of two experiments on HLA-matched donors). An effective response occurred even at very low stimulator to responder ratios and it was clear that DC showed greater stimulatory activity for this particular secondary T-lymphocyte response than other APC types tested.

DISCUSSION

Blood DC arise from an HLA class II positive, lymphoid sized cell that lacks distinguishing morphological or phenotypic features. These experiments establish that the CMRF-44 antigen is an early distinctive marker of DC maturation and that the majority of CMRF-44 positive cells subsequently coexpress the CD83 antigen. Maturation of murine DC is accompanied by a burst of HLA class II and invariant chain synthesis16 and a similar striking upregulation of HLA class II antigens is seen in these experiments on differentiating human blood DC, intimately accompanied by upregulation of the CMRF-44 antigen. Constitutive and inducible HLA class II expression are probably regulated by different mechanisms17 and the parallel expression of HLA class II and CMRF-44 on DC raises the possibility that CMRF-44 expression may be under similar control as inducible HLA class II. The fact that the gene encoding murine CD83 has been localized to the major histocompatability complex (MHC) region recently18 raises the intriguing possibility that it too may be regulated by similar mechanisms.

The HLA class II positive, lineage negative population found in fresh blood is heterogeneous and includes circulating CD34+ stem cells, blood DC and immature forms of other cell lineages. Under the conditions used in these experiments, it appears that the majority of HLA class II positive, lineage negative cells can acquire the phenotype of DC, although the rate at which this occurs varies between individuals. Monitoring the cells that remain HLA class II positive, CMRF-44/CD83 negative after culture indicates a mixed population of cells, with no evidence of B lymphoid or monocytic commitment. Conceivably antigen loss during the immunoselection involved in purification19 may contribute to this population. It is also possible that some of these cells may represent either less mature cells, which require more time to express lineage-specific antigens, or may be a cell population replenished by cell division. The presence of a heterogeneous subpopulation of HLA class II negative cells is also acknowledged, however, whether any of these populations significantly affect DC differentiation remains unclear. The existence of the CMRF 44+/CD83−, intermediate stage of DC differentiation identified in these experiments is supported by the phenotypic similarities these cells have with mature DC (Table 1), and their expression of CD83 after longer culture periods or in the presence of additional cytokines. This phenotype may be useful in identifying tissue DC, which have been partially activated in vivo.

In vivo, maturation of DC precursors has been considered to occur in two stages. Initial changes occur in tissues and further activation/differentiation to a fully mature/activated phenotype typically occurs on migration to a lymph node. In these in vitro experiments, a similar, biphasic maturation was seen over a relatively short time period. Both TNFα and GM-CSF can initiate this process in vitro20 (as can other cytokines to a lesser extent – perhaps via indirect effects), but whether these signals are prerequisites for in vivo DC lineage commitment is still unclear. The identification of a small CMRF-44+, maturing DC population in blood is in keeping with other reports of a similar population21 and suggests there is a basal level of DC generation from precursors, which can be substantially augmented in the presence of inflammatory cytokines. The observation that 10% FCS supported DC maturation better than a combination of GM-CSF, TNFα, and IL4, when added to serum-free media, suggests that other factors may be important to in vivo DC maturation, as does the preservation of normal DC production seen in GM-CSF gene-targeted knockout mice.22

The blood DC, which appear to have undergone a degree of activation, may have been activated via interactions with T lymphocytes or endothelial cells, although it is possible that even the minimal cell handling before culture might induce CMRF-44 expression. Increased surface expression of the CD40, CD80, and CD8623,24 molecules, which contribute significantly to DC costimulation, accompanies the CMRF-44 upregulation during DC activation/maturation. It is interesting to note that CD25 (IL-2Rα) expression also upregulates on DC during this process. The absence of a fully activated CMRF-44 bright DC population may argue partly against the existence of a recirculating population of activated blood DC and the two activation states of DC we have documented in freshly isolated cells might explain the apparent heterogeneity of blood DC observed by others.25

Uptake and processing of antigen has been reported to be most efficient in immature DC5,9 and much of the antigen processing ability of cytokine cultured murine DC has recently been shown to be attributable to the persistence of immature cells.26 MHC-DR molecules synthesized during activation are more stable and remain on the surface of DC for longer than those expressed constitutively.16 Pulsing blood DC with antigen during this process of HLA class II synthesis may optimize antigen DC loading for therapeutic purposes. It is significant, therefore, that the mechanisms of DC antigen uptake appear to be active in CMRF-44 purified DC, as supported by the ability of the 12-hour cultured DC to process and present the soluble antigen KLH in a primary response and both protein (TT) and peptide (bcr-abl) antigens in secondary responses.

A potential T lymphocyte effect on late DC maturation mediated via CD40L/CD40 was noted here, further emphasized by the CD40L/CD40-mediated enhancement of blood DC costimulator molecule expression seen previously.23,27 Full DC differentiation and activation of costimulator activity probably requires interaction with T lymphocytes and this may impart a degree of antigen specificity to DC activation. This is interesting in view of recent suggestions that the signals that activate DC influence whether tolerance or immunity result from a DC-T cell interaction.28,29 While the viability of our sorted DC was higher than that previously reported,30 these rather low survival figures may provide a second line of evidence for activated DC dependence on interactions with other cells, particularly antigen-specific encounters with T lymphocytes, to attain a state of full maturation.

DC appear the logical APC for immunotherapeutic applications, providing sufficient cells can be obtained via clinically acceptable protocols. Efficient antigen loading into purified DC may enable the generation of T responses against some antigens, which otherwise would not provoke an in vivo response. Cell preparations containing DC obtained from precursors cultured in cytokine mixtures are efficient APC and can be generated in relatively large numbers, however, the use of these heterogeneous populations in a clinical setting raises several concerns. First, the extended period of in vitro culture maximizes exposure to auto antigens. Second, the high cytokine concentrations used in these cultures may result in aberrant cell function, including possible resistance to normal regulatory mechanisms. Third, the contaminating cells may induce counterproductive outcomes, either by producing cytokines such as IL-10 or TGFβ or by altering the balance of costimulatory signals, thereby influencing whether or not T lymphocytes are activated efficiently following T-cell receptor (TCR) engagement31 or modifying the cytokine profile of responding T lymphocytes.32 Moreover, the methods used to produce cytokine-generated DC vary, and both the cell types generated and their relative number may differ between laboratories.

The use of blood DC purified without a prolonged in vitro culture period or additional cytokines might simplify attempts to use DC in a clinical setting. Furthermore, manipulation of DC to direct T lymphocyte responses in vitro would be best addressed using purified DC. These purified populations can also be used for studying DC antigen uptake, processing, and control of costimulator function at the cellular or molecular level. Variables to be considered (apart from APC numbers) include the dose of antigen,33 the form of antigen processed by the DC,34 and the possibility of activation-induced T lymphocyte or DC death.35 Given the potency of DC, large numbers of DC may not be necessary to successfully generate an in vivo T-lymphocyte response and the efficacy and safety of relatively small numbers of freshly isolated DC has already been demonstrated in humans.36

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Aaron Rae and Lisa Whyte for expert FACS assistance and Amanda Boyce for technical assistance. We thank Susan Banks for her help in preparing the manuscript.

Supported by grants from the New Zealand Health Research Council, The Cancer Society of New Zealand, The Canterbury Medical Research Foundation, and Canterbury Health Laboratories.

Address reprint requests to Professor D.N.J. Hart, MD, Haematology Department, Christchurch Hospital, PO Box 151, Christchurch, New Zealand.