Visual Abstract

Coagulation factor IX plays a central role in hemostasis through interaction with factor VIIIa to form a factor X–activating complex at the site of injury. The absence of factor IX activity results in the bleeding disorder hemophilia B. This absence of activity can arise either from a lack of circulating factor IX protein or mutations that decrease the activity of factor IX. This review focuses on analyzing the structure of factor IX with respect to molecular mechanisms that are at the basis of factor IX function. The proteolytic activation of factor IX to form activated factor IX(a) and subsequent structural rearrangements are insufficient to generate the fully active factor IXa. Multiple specific interactions between factor IXa, the cofactor VIIIa, and the physiological substrate factor X further alter the factor IXa structure to achieve the full enzymatic activity of factor IXa. Factor IXa also interacts with inhibitors, extravascular proteins, and cellular receptors that clear factor IX(a) from the circulation. Hemophilia B is treated by replacement of the missing factor IX by plasma-derived protein, a recombinant bioequivalent, or via gene therapy. An understanding of how the function of factor IX is tied to structure leads to modified forms of factor IX that have increased residence time in circulation, higher functional activity, protection from inhibition, and even activity in the absence of factor VIIIa. These modified forms of factor IX have the potential to significantly improve therapy for patients with hemophilia B.

Introduction

Factor IX (FIX) plays a pivotal role in promoting coagulation, which is underlined by the fact that a partial or complete deficiency in FIX causes the rare bleeding disorder hemophilia B. Zymogen FIX is proteolytically activated by the enzymatic tissue factor-FVIIa complex upon vascular damage and by activated FXI (FXIa) via thrombin-mediated feedback activation. Activated factor IX (FIXa) assembles with cofactor VIIIa on anionic phospholipids in the presence of Ca2+ ions into the intrinsic tenase complex to catalyze the proteolytic activation of FX, thereby enhancing thrombin formation. Since the original reporting of FIX in 1952 as “Christmas factor”1 named after one of the first identified patients with hemophilia B, research focusing on FIX(a) structure-function and its life cycle has advanced progressively. The knowledge gained continues to inspire and support the development of therapeutic strategies for the treatment of hemophilia. The current review focuses on the state of the art of FIX(a) structure-function research, provides an overview of FIX engineering as a basis for therapeutic advancements, and sketches an outlook for unexplored questions and challenges to be solved in this field.

Structure and function of FIX(a)

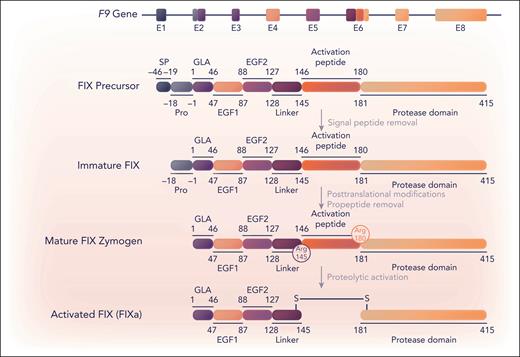

Although FIX messenger RNA or protein can be detected at low levels in several tissues, including endothelial cells,2,3 FIX is only expressed at significant levels in the liver,2 specifically in hepatocytes.4 FIX is a vitamin K–dependent protein that is produced in liver hepatocytes in a precursor state consisting of an N-terminal signal peptide, a propeptide, a γ-carboxy glutamic acid (Gla) domain, 2 epidermal growth factor (EGF) domains, an activation peptide, and a C-terminal serine protease domain (Figure 1). The signal peptide mediates transport into the endoplasmic reticulum, where FIX converts to an immature state (Figure 1). The propeptide facilitates recognition by and interactions with the γ-glutamyl carboxylase enzyme.5 This enzyme posttranslationally γ-carboxylates the 12 Glu residues in the Gla domain, thereby converting these into “Gla” residues.6 The vitamin K–dependent γ-carboxylation reaction is important for the biological activity of FIX and other vitamin K–dependent proteins. This is because the highly negatively charged Gla residues coordinate interactions with Ca2+ ions to lock the Gla domain into a conformation that binds negatively charged phospholipid surfaces, like those of activated platelets, thereby confining coagulation to the site of injury. In FIX, the 11th and 12th Gla (Glu36 and Glu40 in the legacy numbering of mature FIX) are nonessential in the FIX function.7 After γ-carboxylation, the propeptide is removed by limited proteolysis before the secretion of the mature protein. Other posttranslational modifications include glycosylation of the activation peptide, which affects the FIX half-life (posttranslational modifications are reviewed by Hansson and Stenflo8). Mature FIX exists as an inactive single-chain zymogen comprising 415 amino acids (Mr ≈ 55 000 Da; Figure 1).

Schematic representation of F9, FIX, and FIXa. Eight exons (E1-8) in the F9 gene (32.7 kb)133 encode (parts of) specific FIX (UniProt, P00740) protein regions, which are indicated by corresponding colors. FIX protein maturation and activation are schematically depicted and proceed via a precursor and immature protein state to posttranslationally modified mature FIX and FIXa. The signal peptide (SP), propeptide (Pro), Gla, EGF1, EGF2, linker region, activation peptide, and (serine) protease domain regions are defined by legacy numbering, in which residue 1 corresponds to the first amino acid of the Gla domain. Proteolytic activation represents limited proteolysis by extrinsic tissue factor-FVIIa and intrinsic FXIa at the cleavage sites Arg145 and Arg180 generating FIXa. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

Schematic representation of F9, FIX, and FIXa. Eight exons (E1-8) in the F9 gene (32.7 kb)133 encode (parts of) specific FIX (UniProt, P00740) protein regions, which are indicated by corresponding colors. FIX protein maturation and activation are schematically depicted and proceed via a precursor and immature protein state to posttranslationally modified mature FIX and FIXa. The signal peptide (SP), propeptide (Pro), Gla, EGF1, EGF2, linker region, activation peptide, and (serine) protease domain regions are defined by legacy numbering, in which residue 1 corresponds to the first amino acid of the Gla domain. Proteolytic activation represents limited proteolysis by extrinsic tissue factor-FVIIa and intrinsic FXIa at the cleavage sites Arg145 and Arg180 generating FIXa. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

Serine protease FIXa

The transition of the FIX zymogen into its fully active protease state FIXa also referred to as FIXaβ, requires limited proteolysis at cleavage sites Arg145 and Arg180 (Figure 1). Both the extrinsic tissue factor-FVIIa complex9 and intrinsic FXIa10 are capable of catalyzing these reactions, enabling the release of the activation peptide. The activation intermediates of FIX exhibit various levels of catalytic activity. Cleavage of Arg180 results in FIXaα, which has reduced catalytic activity.11,12 This activity can be explained by the mechanism of serine protease domain maturation. Here, the newly formed Val181 N-terminus inserts into the serine protease domain and forms an ionic bond with the highly conserved active-site residue Asp364 (corresponding to Val16c and Asp194c, respectively, in chymotrypsinogen numbering13). This interaction generally prompts conformational rearrangements that ensure the proper alignment of the active site, allowing cofactor binding and substrate catalysis.14 With cleavage at only Arg145 leading to FIXα, this rearrangement cannot occur, and FIXα is catalytically inactive. Patients with mutations such that FIX can only be cleaved at residues 145 or 180 have the expected phenotypes of severe and mild hemophilia B, respectively.15,16

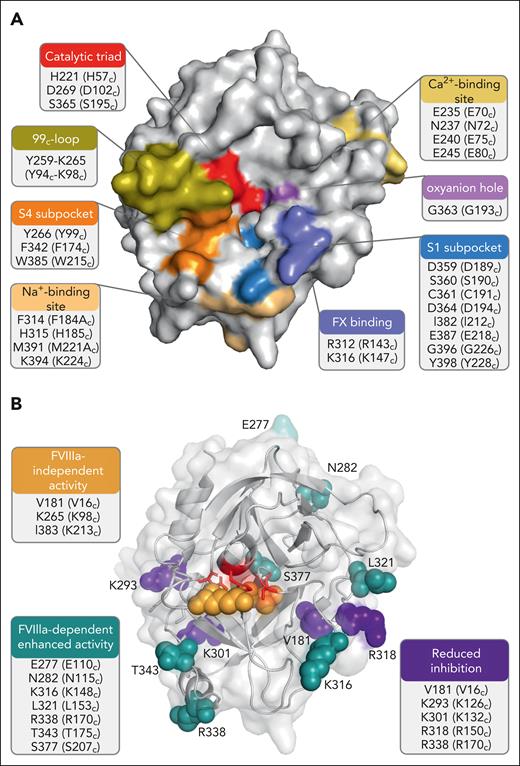

FIXa is a 2-chain serine protease (Mr ≈ 45 000 Da) and comprises a 145-residue light chain (Mr ≈ 17 000 Da) and a 235-residue heavy chain (Mr ≈ 28 000 Da), which are covalently linked via a disulfide bond (Figure 1). The heavy chain consists of a serine protease or catalytic domain, displaying the typical serine protease architecture of 2 β-barrel domains consisting of 6 β-sheets each, with the active-site cleft as the interface. The active site is hallmarked by the catalytic triad residues His221, Asp269, and Ser365 (His57c, Asp102c, and Ser195c; Figure 2A). The catalytic triad, in conjunction with the active-site oxyanion hole residues Gly363 and Ser365 (Gly193c and Ser195c), regulates substrate cleavage, whereas the active-site subpockets (S1-4) control substrate recognition and binding.17 The serine protease domain of FIXa further features an FX recognition site,18 a heparin-binding site,19 a high-affinity Ca2+-binding site,20 and an Na+-binding site.21,22

FIXa serine protease domain. Three-dimensional representations of the FIXa serine protease domain (Protein Data Bank ID 6MV4)22 with identification of the functional regions (A) and residues targeted for substitutions (B) that have been associated with enhanced FIX activity as a result of enhanced FVIIIa-dependent activity, FVIIIa-independent activity, or reduced inhibition. The figures were created with PyMol and BioRender.com.

FIXa serine protease domain. Three-dimensional representations of the FIXa serine protease domain (Protein Data Bank ID 6MV4)22 with identification of the functional regions (A) and residues targeted for substitutions (B) that have been associated with enhanced FIX activity as a result of enhanced FVIIIa-dependent activity, FVIIIa-independent activity, or reduced inhibition. The figures were created with PyMol and BioRender.com.

Unlike other serine proteases, the FIXa structure has evolved to be subjected to strict regulatory mechanisms. The FIXa active site is uniquely controlled by the 99c-loop (Tyr259-Tyr266 or Tyr94c-Tyr99c), which is located directly adjacent to the S4 subsite and blocks access to the active-site pocket (Figure 2A).23 As a result, FIXa alone is incapable of macromolecular substrate conversion at physiologically meaningful rates. The complexation of FIXa with the nonenzymatic cofactor FVIIIa and its substrate FX into the intrinsic tenase complex induces a conformational change that allows for optimal active-site engagement and substrate catalysis.24-26 Although the exact molecular mechanism of conformational activation is not fully understood, it involves stabilization of the open conformation of the 99c-loop, for which both substrate and cofactor binding are required.27,28 Both interactions induce additional allosteric changes in the protease and EGF2 domains, facilitating the transition to a fully active FIXa protease conformation.27,28 The cofactor-mediated modulation of FIXa activity is considered to be tightly regulated29 and FVIIIa further stabilizes the binding interactions with FX. In addition, the negatively charged lipid surface decreases the binding affinity (Km) of substrate FX for FIXa or the tenase complex (Table 1). Assembly into the tenase complex dramatically increases the catalytic rate (kcat) and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of FX conversion (Table 1). The importance of FVIII(a) in coagulation is underscored by the fact that similar to FIX, a partial or complete deficiency is the cause of the bleeding disorder hemophilia A.

Interactions facilitating intrinsic tenase assembly

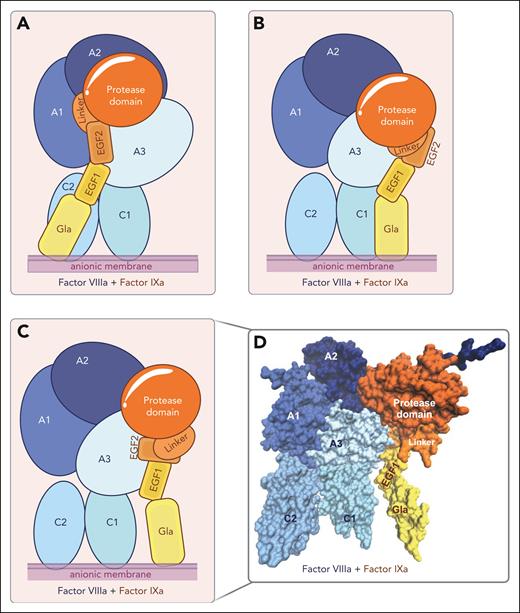

After almost half a century of research, the molecular details of the FIXa-FVIIIa complex assembly and functioning have been partially resolved. Experimentally solved structural models of the intrinsic tenase complex to elucidate these intricate details have proven to be difficult to obtain. Limitations in generating these include the high molecular weight of the overall complex, the presence of posttranslational modifications in both FIXa and FVIIIa, the inherent instability of FVIIIa, and the high flexibility of specific surface-exposed FVIIIa regions. The assembly of the intrinsic tenase complex is membrane-dependent, which limits the reaction dimensions and enhances local concentrations, facilitating productive interactions. The requirement for anionic phospholipids in the FIXa-FVIIIa complex assembly further interferes with classic X-ray analysis techniques to generate 3-dimensional structures. Nevertheless, several structural models of intrinsic tenase have been generated in silico (Figure 3),30-34 in which global information on the assembly of the homologous protease FXa and cofactor FVa into the prothrombinase complex35,36 has been combined with available structural information27,32,33 on FIXa and FVIIIa, and findings on interactive regions obtained in biochemical functional studies.37-46

Structural models of the intrinsic tenase complex. (A-C) Schematic representation of FIXa-FVIIIa structural models assembled on a negatively charged lipid surface (anionic membrane) by Childers et al33 (A), Venkateswarlu32 (B), and Madsen et al34 (C). (D) Three-dimensional surface representation of the FIXa-FVIIIa structural model developed by Madsen et al.34 The individual domains of FIXa (in yellow-orange) and FVIIIa (blue) are indicated. Figures were created with VMD 1.9.3. and BioRender.com.

Structural models of the intrinsic tenase complex. (A-C) Schematic representation of FIXa-FVIIIa structural models assembled on a negatively charged lipid surface (anionic membrane) by Childers et al33 (A), Venkateswarlu32 (B), and Madsen et al34 (C). (D) Three-dimensional surface representation of the FIXa-FVIIIa structural model developed by Madsen et al.34 The individual domains of FIXa (in yellow-orange) and FVIIIa (blue) are indicated. Figures were created with VMD 1.9.3. and BioRender.com.

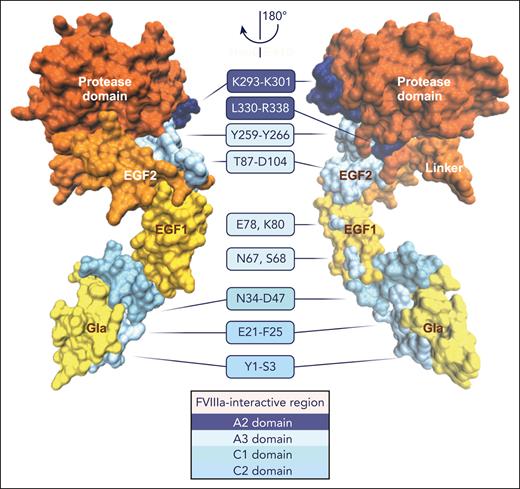

An overview of the interactive regions between FIXa and FVIIIa derived from molecular models and functional studies is provided in Table 2, and the FVIIIa-binding sites identified in FIXa are shown in Figure 4. Studies using synthetic peptides of the FIX Gla domain41 or FVIII C2 domain43 in binding assays or functional assessments have revealed a role for specific Gla domain residues in the interaction with the FVIII C2 domain. A recent model of the FIXa-FVIIIa protein-protein complex assembled on a lipid nanodisc surface obtained by computational protein-protein docking and small-angle X-ray scattering by Childers et al33 confirmed these findings and extended this interactive region to encompass the Gla-EGF1 connecting residues Val46-Asp47 (Figure 3A). However, the orientation of the FIXa Gla domain toward the FVIIIa C2 domain in this model is in disagreement with earlier models of FIXa-FVIIIa30,32,34 and the homologous FXa-FVa complex,35,36 which indicates that the FIXa Gla domain is positioned close to the FVIIIa C1 domain (Figure 3B-D). FIXa-FVIIIa protein-protein docking and molecular dynamics simulations by Venkateswarlu32 indicated that the Gla-EGF1 connecting region Asn34-Asp47 interacts with the FVIII C1 domain (Figure 3B). The FIXa-FVIIIa model generated by Madsen et al34 based on membrane binding of the Gla and C1/C2 domains and coordination of the homologous FXa-FVa complex,35 demonstrated no direct interaction between the FIXa Gla and FVIIIa C1 domains (Figure 3C-D). Despite this, the FIXa orientation relative to the FVIIIa A3 domain showed similarities, as in each of the aforementioned models, EGF1 stretches along the A3 domain (Figure 3B-C), with the putative interactive regions in the A3 domain being dependent on the positioning of the FIXa Gla domain relative to the FVIIIa C domains. Kinetic assessments of recombinant FIX38,42 and FVIII44,46 variants, as well as computational FIXa-FVIIIa models,32,34 indicated that the EGF2 domain interacts with the FVIIIa A3 domain. Although not directly involved in FVIIIa binding, both the interface between EGF1-EGF2 and that between EGF2 and the protease domain are essential for intrinsic tenase assembly and activity,37,38,40,42 as these interactions likely direct geographical domain orientation. Structural models of both FIXa-FVIIIa and of the homologous FXa-FVa complex35,36 indicate some ambiguity regarding the exact positioning of the FIXa protease domain relative to FVIIIa32,33 (Figure 3). Computational models and experimental evidence point to direct interactions between the FIXa protease domain and the A2-A3 domains in FVIIIa. Small-angle X-ray scattering analysis of the intrinsic tenase indicated that the 99c-loop interacts with the A3 domain,33 which is in agreement with earlier kinetic analyses of recombinant FVIII variants.44,46 A cluster of solvent-exposed helices that together form a basic surface region, also known as exosite II, interacts with various regions in the FVIIIa A2-A3 domains and acidic a2 region.27,32,39,45,46 Specific FIXa regions involved in the interaction with the natural substrate FX are reported to include Arg312 and Lys316 (Arg143c and Lys147c).18 In addition, FX has been suggested to bind (close) to the FIXa 99c-loop via its activation peptide, facilitating the conformational activation of FIXa.47,48

FVIIIa-interactive regions in FIXa. Structural model of FIXa34 in which the putative regions interact with the FVIIIa A2 domain (dark blue), A3 domain (pale cyan), C1 domain (cyan), or C2 domain (light blue) are indicated. FIXa is shown in 2 orientations rotated 180° along the y-axis, and the individual FIXa domains are denoted. A detailed overview of the FIXa and FVIIIa regions is provided in Table 2. The figure was created with VMD 1.9.3. and BioRender.com.

FVIIIa-interactive regions in FIXa. Structural model of FIXa34 in which the putative regions interact with the FVIIIa A2 domain (dark blue), A3 domain (pale cyan), C1 domain (cyan), or C2 domain (light blue) are indicated. FIXa is shown in 2 orientations rotated 180° along the y-axis, and the individual FIXa domains are denoted. A detailed overview of the FIXa and FVIIIa regions is provided in Table 2. The figure was created with VMD 1.9.3. and BioRender.com.

FIX mutations in hemophilia B

The F9 gene is located on chromosome Xq27.1 and consists of 8 exons encoding various FIX domains (Figure 1). Of the F9 gene variants leading to hemophilia B, 66% are located throughout all 8 exons and represent 1692 unique pathogenic variants identified thus far.49,50 These pathogenic variants include missense, nonsense, and splice site variants, deletions, and insertions that cause a shift in the reading frame or, in rare cases, partial gene duplications. Synonymous mutations have also been described that modulate FIX functionality through, for example, aberrant splicing, intracellular trafficking, or truncated protein synthesis.51-53 An extensive overview is provided in F9 gene variant databases,49,54-56 of which https://www.factorix.org/49 has been most recently updated and provides additional predictions of the structural implications for all missense mutations. Moreover, the molecular effects of ∼9000 individual pathogenic mutations in FIX, including those in the signal peptide and propeptide, have been characterized recently.57,58 Notably, in ∼1% of patients with hemophilia B, no gene variation has been identified,59 suggestive of other molecular mechanisms that may cause FIX deficiencies. Detailed information on the F9 gene variant is relevant for, among others, genetic counseling and disease management, including personalized therapeutic strategies to overcome specific mutations. Furthermore, disease classification is essential for risk assessment of developing inhibitory antibodies that target FIX therapeutics. A type I, or quantitative, disorder is characterized by low levels of plasma FIX antigen, with no detectable FIX antigen indicated as cross-reacting material (CRM)–negative. In type II, or qualitative, disorder patients are CRM-positive and their disease severity is categorized as mild (6%-40% FIX clotting activity), moderate (1%-5% FIX clotting activity), or severe (<1% FIX clotting activity). In the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hemophilia B database54 of 1132 mutations, 23% were mutations that could be associated with a type I disorder, and the remaining 77% were associated with mutations that would be expected to be type II disorders. Twenty-four patients (2%) had a history of inhibitor development, and 92% of those patients had a mutation associated with a type I disorder. These results are consistent with those of the European Paediatric Network for Haemophilia Management study60 and a nationwide Chinese study61 indicating that, as in hemophilia A, large deletions and nonsense mutations are associated with a higher rate of FIX inhibitor formation.

FIX modifications to extend half-life

The development of recombinant FIX products for replacement therapy was made possible by the cloning of the FIX gene in 1982.62 The first generation of recombinant FIX products was licensed in 1997/98 and displayed standard half-lives similar to those of plasma FIX. The second-generation recombinant FIX products that were first approved between 2014 and 2017 have been modified to extend the circulating FIX half-life, allowing for a reduction in treatment frequency. Generally, these recombinant FIX products are bioengineered using codon optimization to achieve optimized protein expression through enhanced messenger RNA levels and/or stability.63 Although there are concerns for enhanced immunogenicity regarding recombinant FIX made by technologies that use codon optimization64 and nonhuman cells for production, to date, the data from clinical trials and postmarketing surveillance have patient numbers too low to draw a conclusion regarding immunogenicity.65 An overview of current FIX-based products approved for hemophilia B treatment is provided by the Coalition for Hemophilia B.66 Insight into the modulators of FIX half-life is essential for understanding and improving the efficacy of current and future FIX therapeutics.

Extending the intravascular half-life of FIX

Zymogen FIX circulates in plasma at a concentration of 4 to 5 μg/mL (∼90 nM) with a circulating half-life of 18 to 24 hours.67 Similar to other coagulation factors, FIX is considered to be cleared by the liver, specifically by the hepatocytes.68 Surprisingly, the available observations on specific receptors and/or proteins that contribute to FIX clearance are limited, and as a consequence the exact mechanism is poorly understood. The FIX activation peptide is known to modulate circulating FIX levels, which is mediated by N-linked and O-linked glycosylation of this region.69-71 Both N-linked and O-linked glycans of plasma-derived FIX are terminated by sialic acid groups, with recombinant FIX having somewhat variable levels of sialylation.72-74 In vitro observations indicate that glycan groups in zymogen FIX, and as such, the activation peptide lacking terminal sialic acids, are targeted by the hepatocyte–expressed asialoglycoprotein receptor.68 However, no effect on plasma FIX levels was observed in asialoglycoprotein receptor–deficient mice.75 Whether and when removal via the asialoglycoprotein receptor contributes to the clearance of recombinant and/or plasma FIX requires further study. Low-density lipoprotein–related protein-1 (LRP1), a receptor expressed on hepatocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells, among other cell types, has been shown to interact with the FIXa protease in vitro.76 Although FIXa clearance has not been evaluated further in murine LRP1 deficiency, these in vivo models indicated no role for LRP1 in FIX clearance, as plasma FIX levels were unaffected.77

Recombinant FIX products with an extended circulating FIX half-life are characterized by a three- to fivefold increase in T1/2, allowing less frequent FIX infusions to maintain prophylactic trough levels of >1% FIX clotting activity. Strategies to prolong the FIX half-life include site-specific glycopegylation, in which polyethylene glycol (PEG) molecules are attached to the N-glycan structures at Asn157 and Asn167 in the FIX activation peptide to prevent interference with FIXa function, thus generating glycoPEGylated FIX (N9-GP, nonacog beta pegol).70 The hydrophilic nature of PEG molecules hampers their clearance via the glomerular filter, thereby reducing renal clearance. Fc or albumin fusion takes advantage of protein recycling by the neonatal Fc receptor located on monocytes/macrophages and endothelial cells. By fusing FIX to the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G1 (FIXFc, eftrenonacog alpha) or albumin (albutrepenonacog alfa), FIX escapes the lysosomal degradation pathway that targets all plasma proteins and is recycled back into the circulation.78,79 Alternatively, other strategies may be exploited to prolong half-life, such as fusion with the FXIII B subunit that extends the FIX half-life by fourfold in wild-type mice,80 likely via FXIIIB interaction with fibrinogen and albumin.81 A future third generation of FIX products may combine further prolongation in T1/2 with enhanced FIX function to reduce the administration frequency. Recently, a novel variant was engineered in which albumin, modified to display enhanced neonatal Fc receptor binding, was fused to a FIX species with higher specific activity (FIX-Padua), thereby extending the half-life and improving FIX activity.82

Extending the FIX half-life via extravascular distribution

In addition to circulating in plasma, FIX is known to be present in the extravascular space. Over the past 30 years, seminal findings by Stafford et al have advanced our understanding of the contribution of extravascular FIX to hemostasis. Facilitated by the Gla domain residues Lys5 and Val10,83,84 FIX interacts with the extracellular matrix protein collagen IV,85 which is a major component of the endothelial basement membrane. Extravascular localization of FIX was further suggested in murine models of hemophilia B, demonstrating that postinfusion recovery in circulation was higher for FIX-Lys5Ala, which does not interact with collagen IV,84 relative to wild-type FIX.86,87 Support for a contribution of extravascular FIX to hemostasis came from studies in which transgenic mice expressing FIX-Lys5Ala showed lower hemostatic activity than normal mice upon vascular injury in which basement membrane collagen IV was exposed.87,88 In addition, infusion of wild-type FIX into hemophilia B mice was shown to lead to prolonged hemostatic efficacy in vascular injury models despite undetectable circulating plasma FIX.87,89 The potential impact of extravascular endogenous FIX storage on hemophilia B therapy was evaluated in hemophilia B mice with either a CRM-negative or CRM-positive status. Assessment using a bleeding model indicated that wild-type FIX achieved better hemostasis in CRM-negative vs CRM-positive mice.89 This implies that endogenous dysfunctional FIX variants in CRM-positive patients with hemophilia B may negatively affect the efficacy of FIX treatment by occupying extravascular sites. The exact location of the extravascular FIX reservoir is not known. Histological analyses of murine86,90 and human89 tissues indicate that FIX is distributed in close proximity to vessels and hepatocytes. Dargaud et al90 recently demonstrated FIX to also reside in the knee joints of mice after regular FIX administration. In the latter case, FIX colocalized with collagen I, and a direct interaction between collagen I and various FIX products was confirmed in vitro.90 In summary, the pool of extravascular FIX seems to be limited to areas proximal to vessels, hepatocytes, and joints. Both standard (plasma-derived and recombinant FIX) and extended half-life FIX products have been shown to interact with collagen I and IV.90 Among the extended half-life products, clinical pharmacokinetic properties,91 and murine biodistribution data92 suggest FIXFc to distribute in the extravascular space. FIX variants with enhanced binding affinities for collagen I or IV may improve the hemostatic efficacy of FIX products, as has been shown in vivo for FIX-Lys5Arg, which displays enhanced binding to collagen IV.85-87 Importantly, the physiological relevance of extravascular FIX or its role in FIX half-life has not been unequivocally established thus far. Although speculative, the general consensus is that the sequestering of FIX to extravascular sites supports local coagulation using the extracellular matrix as a scaffold.88-90,93 Whether extravascular FIX also serves as a depot affecting the FIX plasma half-life and impacts the treatment of CRM-positive patients with hemophilia B merits future exploration.

FIX modifications that enhance activity

Although enhanced levels of plasma FIX are known to be a strong risk factor for venous thrombosis,94 specific FIX mutations associated with venous thrombosis are rare. The only substitutions known to predispose to X-linked thrombophilia are Arg338Leu (Arg170cLeu) in FIX-Padua and Arg338Gln (Arg170cGln) in FIX-Shanghai, which induce an eight- to fivefold increase in specific clotting activity, respectively (Figure 2B).95,96 The hyperactivity of FIX-Padua has been suggested to result from enhanced FVIIIa-induced conformational activation of FIXa,97 consistent with the putative interaction of Arg338 with FVIIIa (Table 2). Interestingly, in vitro screening of all possible amino acid replacements at position 338 revealed FIX wild-type to display the lowest FIX activity, suggesting that Arg338 is evolutionarily conserved to constrain FIX activity.29 Hyperfunctional FIX as a result of Arg338Ala or Arg338Gln replacements has been exploited for in vivo gene therapy studies.96,98 Moreover, gene therapy using FIX-Padua as a transgene has recently been approved for the treatment of patients with hemophilia B.99

Molecular insights into FIXa function in analogy with other clotting serine proteases have led to the rational design of novel FIX variants for therapeutic purposes. One variant with a reported higher in vivo efficacy than FIX-Padua combines the Arg338Glu (Arg170cGlu) substitution with Thr343Arg (Thr175cArg), which likely improves the FVIIIa-dependent enhancement of FIXa activity, and with Arg318Tyr (Arg150cTyr), which reduces antithrombin inhibition (Figure 2B).100,101 This molecule, dalcinonacog alfa, has sufficiently high activity that therapeutic levels via subcutaneous injection might be possible and has been evaluated in phase 2 clinical trials.102,103 Other FIX variants displaying high specific clotting activity and in vivo efficacy combine the FIX-Padua mutation with (1) Val10Lys, which hampers collagen IV binding, and Ser377Trp (Ser207cTrp) conferring homology with chymotrypsin, thrombin, FVIIa, and FIXa,104 or (2) Val86Ala and Glu277Ala (Glu110cAla), which enhances the binding affinity for FVIIIa (Figure 2B).105,106 Using ancestral sequence reconstruction, Doering et al107 have engineered the FIX variant ET9 that, in addition to the FIX-Padua substitution, comprises 5 amino acid replacements (Val86Ala, Glu277Lys [Glu110cLys], Asp282Asn [Asp115cAsn], Lys316Arg [Lys148cArg], Leu321Ser [Leu153cSer]; Figure 2B), conferring a 51-fold increase in specific clotting activity. These and other molecules with enhanced activity have enormous potential for reducing the frequency of injections, for therapy via novel injection routes, such as subcutaneous injection, and for improved gene therapy.

FIX modifications that reduce inactivation

The serpin antithrombin is a major downregulator of coagulation and inhibits many serine proteases including FIXa. Ivanciu et al108 recently generated FIXa variants that are protected from antithrombin inhibition due to an immature active-site conformation resulting from destabilized 16c–Asp194c salt bridge formation after Val181Ile (Val16cIle) substitution (Figure 2B). Interaction with FVIIIa rescues procoagulant activity by inducing active protease conformation. Interestingly, despite a substantially reduced specific clotting activity and a >10-fold reduced rate of inhibition by antithrombin, FIX-Val181Ile displayed hemostatic efficacy in murine models of hemophilia B.108 An alternative approach to induce inhibitor resistance involves specific modification of the interactive sites for antithrombin Arg318Ala (Arg150cAla)18,109 and its cofactor heparin (Lys293Ala [Lys126cAla] and Lys301Ala [Lys132cAla]), as previously demonstrated in vitro (Figure 2B).110 Another regulator of FIXa activity is protein S.111 Antibodies against protein S112 and small interfering RNA knockdown of protein S113 have been used in preclinical studies as adjunct therapies to improve the in vivo efficacy of FIX in hemophilia. An alternative approach is suggested by the observation that a combined mutation in FIX of Lys301Ala (Lys132cAla) and Arg338Ala (Arg170cAla) blocks FIXa interaction with protein S and enhances in vivo FIXa activity of FIXa.114 Resistance to circulating FIXa inhibitors antithrombin, protein S, protein Z–dependent protease inhibitor,115 and protease nexin 2116 could be further exploited to expand the repertoire of hemophilia B treatment strategies. Specifically, these could involve modifications to render FIXa less susceptible to these inhibitors or, alternatively, by downregulating the inhibitor activity and/or levels (eg, fitusiran117).

Nontraditional strategies mimicking cofactor functions

A detailed understanding of the role of cofactor FVIIIa has led to several developments aimed at replacing FVIIIa to facilitate unimpeded FIXa-dependent FX conversion as a basis for nontraditional hemophilia A treatment strategies.

Cofactor-independent FIX

FIX variants displaying varying levels of cofactor-independent activity have been generated.118,119 FVIII-independent activity was achieved after the introduction of specific modifications implicated to be important for substrate recognition and binding, including Lys265Ala (Lys98cAla) substitution in the 99c-loop, Val181Ile and Ile383Val (Val16cIle and Ile213cVal) in the S1 active-site subpocket (Figure 2B), and Leu6Phe substitution in the Gla domain, generating FIX-FIAV.118 FIX-FIAV was shown to display an up to fivefold increase in catalytic efficiency toward FX in the absence of FVIIIa in vitro, mitigated blood loss in hemophilia A mice in vivo,118 and increased FVIII-equivalent activity and coagulation activity in the plasma of patients with hemophilia A regardless of current treatment, inhibitor status, or residual FVIII levels.120 These findings suggest that cofactor-independent FIX variants, such as FIX-FIAV, could serve as a potential treatment for patients with hemophilia A with or without inhibitors of FVIII.

FVIIIa mimetics

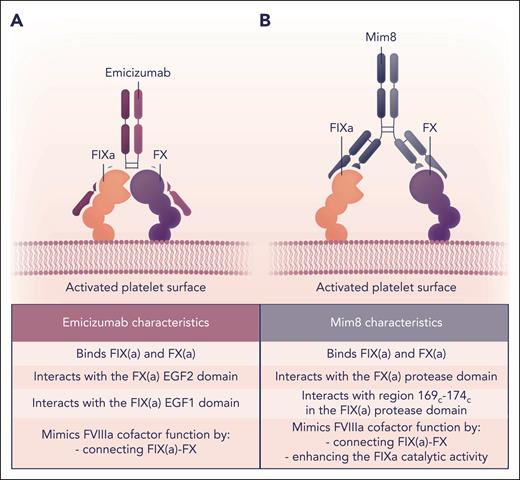

Alternative strategies to mimic FVIIIa function come from the development of bifunctional antibodies that bind FIXa with 1 arm and FX with the other. Emicizumab was the first bispecific antibody developed and binds the EGF1 domain of FIX(a) and the EGF2 domain of FX(a), thereby colocalizing the 2 proteins (Figure 5).121,122 Emicizumab has been used effectively for the prophylactic treatment of patients with hemophilia A with and without inhibitors.123 A modified form of emicizumab, designated as NXT007, with enhanced binding to FX and increased FX activation, is in preclinical development.124

Mode of action of FVIIIa-mimetics emicizumab and Mim8. Schematic representation and comparison of the mode of action of the bispecific antibodies emicizumab (A) and Mim8 (B) that, in part, mimic the FVIIIa cofactor function on negatively charged phospholipid surfaces such as that of activated platelets. (A) Emicizumab interacts with the FIX(a) EGF1 and FX(a) EGF2 domains, thereby bringing FIX(a) and its substrate in close proximity, facilitating FIXa-mediated FX activation. (B) Mim8 specifically binds to the FIX(a) serine protease domain Leu337-Thr343 (Leu169c-Thr174c) and the FX(a) serine protease and EGF2 domains. In addition to localizing FIX(a) and FX close to each other on the membrane surface, Mim8 conformationally activates FIXa catalytic activity directly in a manner similar to FVIIIa. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

Mode of action of FVIIIa-mimetics emicizumab and Mim8. Schematic representation and comparison of the mode of action of the bispecific antibodies emicizumab (A) and Mim8 (B) that, in part, mimic the FVIIIa cofactor function on negatively charged phospholipid surfaces such as that of activated platelets. (A) Emicizumab interacts with the FIX(a) EGF1 and FX(a) EGF2 domains, thereby bringing FIX(a) and its substrate in close proximity, facilitating FIXa-mediated FX activation. (B) Mim8 specifically binds to the FIX(a) serine protease domain Leu337-Thr343 (Leu169c-Thr174c) and the FX(a) serine protease and EGF2 domains. In addition to localizing FIX(a) and FX close to each other on the membrane surface, Mim8 conformationally activates FIXa catalytic activity directly in a manner similar to FVIIIa. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

A different bifunctional antibody, Mim8, is currently in clinical trials.125 Mim8 binds to both FIX(a) and FX(a), but at different sites than emicizumab (Figure 5). The crystal structure of the Fab fragments of antibodies binding to FIXa and FX has been previously published.126 The FIXa-binding arm of Mim8 binds to FIXa in the protease domain. The FX binding arm of Mim8 covers a large region of FX, including parts of both the EGF2 and protease domain. Mim8 not only colocalizes FIXa and FX but also enhances the catalytic activity of FIXa.126 The FIXa-binding arm of Mim8 binds to a peptide of FIXa (169c-174c) that is located immediately adjacent to the 99c-loop and close to the FVIIIa-binding site of 162c-170c (Table 2). The binding of Mim8 to FIXa at this site may facilitate a more active conformation of FIXa. To date, bifunctional antibodies have been efficacious in providing prophylaxis to patients with hemophilia A with inhibitors.127 An advantage of bifunctional antibodies is that they can be administered by subcutaneous rather than IV injection.

Outlook

The treatment of hemophilia B is entering a new era with the approval of gene therapy and clinical development of alternative bypassing strategies. Progress in understanding how FIX function is tied to structure is leading to modified forms of FIX that have increased residence time in circulation, higher functional activity, protection from inhibition, and even activity in the absence of FVIIIa. Although these FIX variants require clinical evaluation to assess their efficacy and immunogenicity, they have the potential to significantly improve therapy for patients with hemophilia B.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jesper Madsen and Divi Venkateswarlu for providing atomic coordinates of the FIXa-FVIIIa structural models.

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant R01-HL151984).

Authorship

Contribution: M.H.A.B. and D.M.M. conceptualized, wrote, and edited the manuscript; and R.E.v.D. provided essential information on intrinsic tenase assembly, designed and prepared figures, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.H.A.B. has received consultancy fees from VarmX B.V. (all fees to the institution) and is an inventor of intellectual property, all unrelated to this work. R.E.v.D. is a former employee of VarmX B.V. D.M.M. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dougald M. Monroe, Department of Medicine and UNC Blood Research Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 8202B Mary Ellen Jones, 116 Manning Dr, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7035; email: dmonroe@med.unc.edu.