In this issue of Blood, Hugon-Rodin et al report important data on the kinetics of hormone and plasma coagulation normalization after cessation of combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs), providing needed data to determine the timing of discontinuation before surgery.1 Sixty-six women with different types of CHCs, mainly oral (83%), provided blood samples before planned discontinuation of the CHC as well as at 1, 2, 4, 6, and 12 weeks afterwards. Samples were also obtained from 26 fertile women who were not using CHCs at 0, 4, and 12 weeks. The authors measured levels of factor VIII, the natural coagulation inhibitors (ie, antithrombin, protein C, and protein S), markers of activation of coagulation (thrombin generation–based normalized sensitivity ratio to activated protein C [nAPCsr] and to thrombomodulin [nTMsr] and endogenous thrombin potential and peak value), and levels of sex hormone–binding globulin.

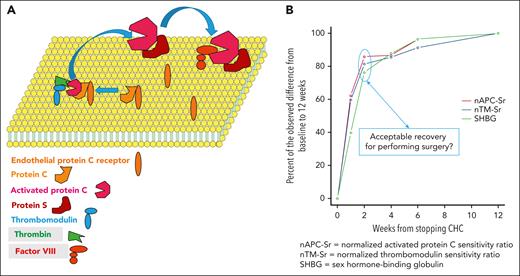

The authors found that most of the change in coagulation activation after CHC cessation occurred within 1 to 2 weeks, with incrementally smaller improvements between each additional time point up to 12 weeks (see figure). This was mirrored by similar changes in the coagulation factors and inhibitors as well as sex hormone–binding globulin levels. At 12 weeks from cessation, all parameters were at or close to the same level as observed in the controls. Protein C was the only parameter that during CHC use changed in the antithrombotic direction (higher levels), and at 4 weeks after cessation it was close to the control level. The kinetics of these variables did not appear to differ between the various CHCs, keeping in mind that few of the patients were on nonoral agents.

Recovery of hemostatic balance after CHC cessation. (A) On a phospholipid bilayer on the endothelial cell, the endothelial protein C receptor together with protein C approach thrombomodulin, which has captured circulating thrombin. Protein C then becomes activated. Together with the cofactor protein S, activated protein C becomes even more efficient in inhibiting activated factor VIII and factor V (not shown). Thus, thrombomodulin and activated protein C are important components in reduction of the thrombin generation that was measured. (B) Kinetics of the recovery to normal, approximated to 12 weeks after discontinuation of CHC.

Recovery of hemostatic balance after CHC cessation. (A) On a phospholipid bilayer on the endothelial cell, the endothelial protein C receptor together with protein C approach thrombomodulin, which has captured circulating thrombin. Protein C then becomes activated. Together with the cofactor protein S, activated protein C becomes even more efficient in inhibiting activated factor VIII and factor V (not shown). Thus, thrombomodulin and activated protein C are important components in reduction of the thrombin generation that was measured. (B) Kinetics of the recovery to normal, approximated to 12 weeks after discontinuation of CHC.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends continuing CHC for surgery with expected ambulation postoperatively but discontinuing CHC 4 to 6 weeks before surgery with anticipated prolonged immobilization.2 This recommendation is “based primarily on consensus and expert opinion” and with level of evidence C. It refers to a study from 1991 reporting that hemostatic changes induced by CHCs appear to be normalized after 1 week (fibrinogen and antithrombin) to 8 weeks (coagulation factor X) from cessation.3 In that study, markers of activation of coagulation were not included. A literature review concluded that the risk of thromboembolism after surgery in patients on CHC or hormonal replacement therapy is counterbalanced by the risk of undesired pregnancy or increase of climacteric symptoms after cessation of the CHC/replacement therapy. Instead, the authors of the review recommended that perioperative prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism should be “moderately strengthened.”4 This strategy is problematic in patients who have undergone major surgery and have a high risk of experiencing postoperative bleeding.

A key study, published in Blood in 2016, found that CHCs do not have to be stopped when a patient develops venous thromboembolism and is treated with an anticoagulant, specifically rivaroxaban.5 Given that the thromboembolic event in these cases will most certainly be considered provoked, therefore requiring only 6 months of anticoagulation,6 the unanswered question is at what time point in relation to discontinuation of anticoagulation should the CHC be stopped or replaced with a non-estrogen method.

The current study by Hugon-Rodin et al sheds light on this murky problem. If there is a need to stop CHCs to minimize the risk of thromboembolism, whether it is before surgery with subsequent immobilization/other risk factors for thrombosis or before planned cessation of anticoagulation, an interval of 2 to 4 weeks is probably sufficient. Indeed, minimal improvement of the prothrombotic parameters occurred between 2 and 4 weeks after cessation of CHC. Critically, this article should be viewed as on surrogate biomarkers, and the study was not designed or intended to show how accurately these reflect the clinical risk of thromboembolism. Furthermore, women with a history of venous thromboembolism or known thrombophilic defects were excluded from participation. Therefore, the results are applicable to patients on CHC with planned major surgery. A multicenter trial comparing intevals of 2 weeks vs 4 weeks between interruption of CHC and major surgery or cessation of anticoagulation should be the next step. Finally, if the CHCs are stopped, the patients should be alerted to the possibility of unwanted pregnancy and informed of alternative contraception options such as progestin-only or barrier methods.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.S. received honoraria from Alexion, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Octapharma, Sanofi, and Servier.