Abstract

Regenerative failure at barrier surfaces and maladaptive repair leading to fibrosis are hallmarks of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Although immunosuppressive treatment can control inflammation, impaired tissue homeostasis leads to prolonged organ damage and impaired quality of life. In this Blood Spotlight, we review recent research that addresses the critical failures in tissue regeneration and repair that underpin treatment-resistant GVHD. We highlight current interventions designed to overcome these defects and provide our assessment of the future therapeutic landscape.

Introduction

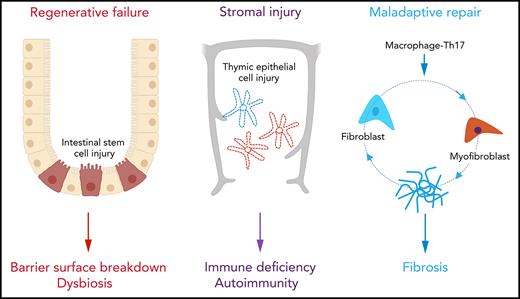

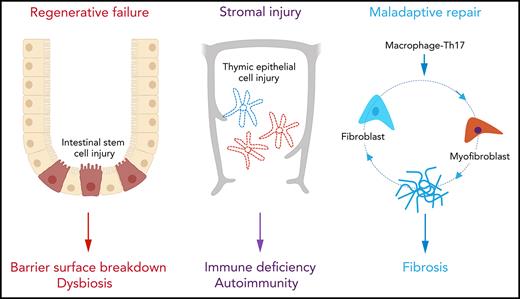

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains a major barrier to successful allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.1,2 Unfortunately, current therapies for GVHD lack precision and rely upon inducing global immune suppression, which contributes to high rates of nonrelapse mortality secondary to infection and an increased risk of blood cancer relapse.1,2 Furthermore, treatment resistance is common and emerges quickly during disease evolution. The recent introduction of JAK1/2 inhibitors still fails to serve as salvage therapy for a significant proportion of patients,3,4 suggestsing that some tissue damage is irreversible. Indeed, disease progression in the face of profound immune deficiency argues that mechanisms other than the magnitude of the alloimmune response are important in influencing the trajectory of GVHD. Wu and Reddy 5 recently proposed a conceptual framework for GVHD pathogenesis in which the structural cells of peripheral tissues play a critical role in regulating the disease course, either through counterregulatory responses to inflammation (immune tolerance)6,7 or through intrinsic properties that allow them to withstand the combined effects of conditioning-induced and immune-related injury (tissue tolerance).5 Although cellular resistance to apoptosis8,9 can confer some components of tolerance, restoration of tissue homeostasis ultimately relies upon regeneration and repair. Healing is normally orchestrated by highly conserved mechanisms involving self-limited activation of the innate immune system (eg, via cytokines such as interleukin-6 [IL-6], tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α], and signaling pathways, such as NF-κB)10,11; however, an early failure to curtail inflammation as a result of adaptive immune reactivity directly interferes with the processes of regeneration and repair in GVHD (Figure 1). In this Blood Spotlight, we summarize recent data demonstrating how GVHD and its treatment disrupt healing and discuss how this information might be used to develop new targeted therapies.

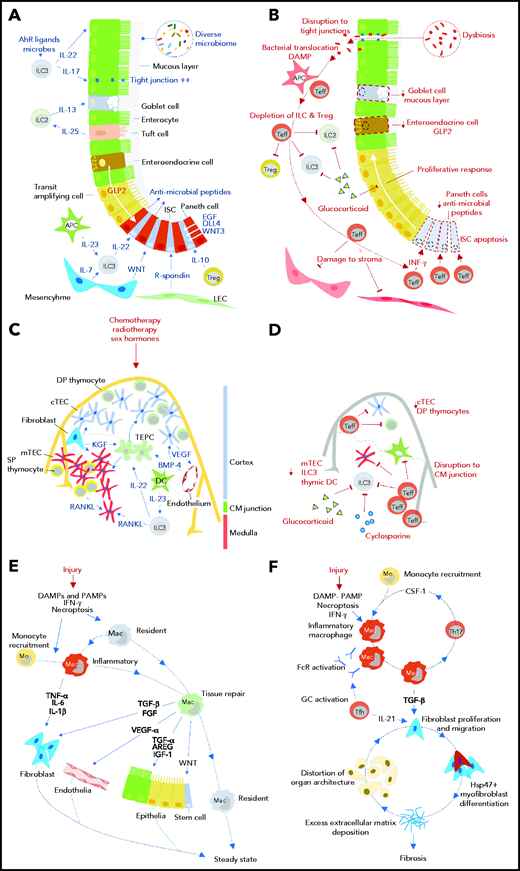

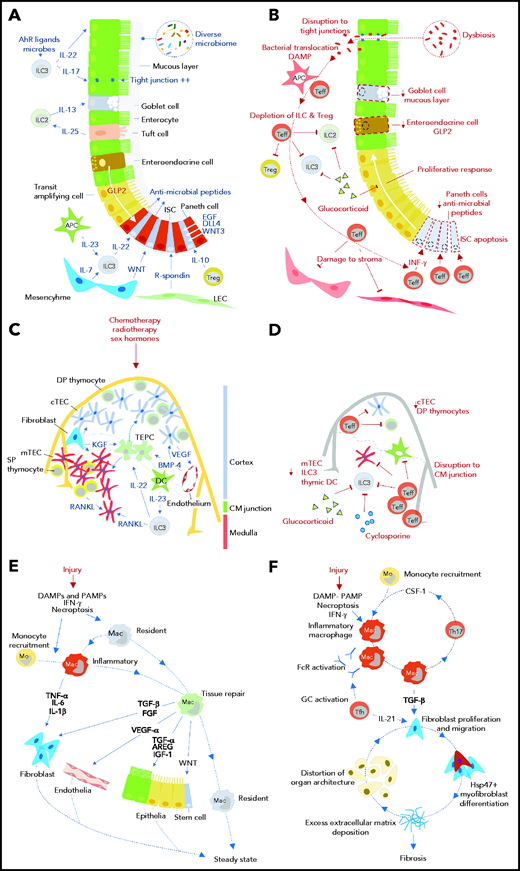

Impact of GVHD on tissue regeneration and repair mechanisms. Tissue responses in steady state and/or the response to acute sterile injury (A, C, E) are compared with those observed during GVHD (B, D, F) for the intestine (A, B), thymus (C, D), and skin/lung (E, F). AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; APC, antigen presenting cell; AREG, amphiregulin; BMP-4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; CM, corticomedullary; cTEC, cortical thymic epithelial cell; DAMP, damage-associated molecular pattern; DC, dendritic cell; DLL4, delta-like ligand 4; DP, double positive; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FcR, Fc receptor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; GC, germinal center; GLP-2, glucagon-like peptide 2 (note was defined in text); Hsp47, heat shock protein 47; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; ISC, intestinal stem cell; KGF, keratinocyte growth factor; LEC, lymphatic endothelial cell; Mac, macrophage; mo, monocyte; mTEC, medullary thymic epithelial cell; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κΒ ligand; SP, single positive; Teff, effector T cell; TEPC, thymic epithelial progenitor cell; Tfh, follicular helper T cell; TGF-α/β, transforming growth factor-α/β; Th17, T helper 17 cell; Treg, regulatory T cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; WNT, wingless-related integration site.

Impact of GVHD on tissue regeneration and repair mechanisms. Tissue responses in steady state and/or the response to acute sterile injury (A, C, E) are compared with those observed during GVHD (B, D, F) for the intestine (A, B), thymus (C, D), and skin/lung (E, F). AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; APC, antigen presenting cell; AREG, amphiregulin; BMP-4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; CM, corticomedullary; cTEC, cortical thymic epithelial cell; DAMP, damage-associated molecular pattern; DC, dendritic cell; DLL4, delta-like ligand 4; DP, double positive; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FcR, Fc receptor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; GC, germinal center; GLP-2, glucagon-like peptide 2 (note was defined in text); Hsp47, heat shock protein 47; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; ISC, intestinal stem cell; KGF, keratinocyte growth factor; LEC, lymphatic endothelial cell; Mac, macrophage; mo, monocyte; mTEC, medullary thymic epithelial cell; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κΒ ligand; SP, single positive; Teff, effector T cell; TEPC, thymic epithelial progenitor cell; Tfh, follicular helper T cell; TGF-α/β, transforming growth factor-α/β; Th17, T helper 17 cell; Treg, regulatory T cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; WNT, wingless-related integration site.

Regenerative failure at barrier surfaces

To maintain tissue homeostasis, the epithelia of the intestine and the skin are characterized by very high rates of cell turnover in the steady state.12 The demands of rapid cell turnover are met by the immense regenerative capacity of tissue-resident adult stem cell populations.11 When stressed by acute, sterile injury (eg, a genotoxic insult such as irradiation), re-epithelialization is conducted by both surviving stem cells and by more committed progenitor cells in the vicinity (eg, transit-amplifying cells [TACs] within crypt-proximal regions or zones of the villus and lower segment hair follicle cells), the latter responding to wingless-related integration site (WNT)-driven signals by dedifferentiating to stem cell–like cells.13,14 Although this plasticity is important in allowing early recovery after time-limited insults, the decline in regenerative capacity associated with aging indicates that stem cell reserve can be finite and may not be sustainable over the long term.14 In GVHD, the immune sensitivity of resident stem cells15,16 combined with the derangement of stem cell–supportive niches17 drastically reduces the capacity for regeneration (Figure 1A-B). Indeed, shortened enterocyte telomeres in biopsies from patients with the most severe forms of intestinal GVHD suggest excessive proliferation and eventual exhaustion of the stem cell pool.18

Histologically, acute GVHD (aGVHD) is characterized by the presence of apoptotic cells spatially restricted to sites that harbor stem cells at the base of the intestinal crypts19 or in the hair follicle bulge or rete ridges of the skin20,21; apoptosis is associated with intestinal crypt drop out,22 or impaired progression to hair follicle growth and wound healing.15 In preclinical models of aGVHD, donor T cells are found in close proximity to Lgr5+ stem cells of the intestinal crypts23,24 and of the bulge region of the hair follicle.15 Although quiescent tissue-resident stem cells can avoid being targeted by T cells through downregulation of the expression of surface major histocompatibility complex molecules, stem cells entering the cell cycle (eg, in response to irradiation25) and/or responding to local microbiota24 upregulate major histocompatibility complex molecules thereby increasing their sensitivity to immune attack.

Erosion of epithelial stem cell reserve in GVHD is further reinforced by disruption to local epithelial-stromal-immune microenvironments that normally operate to protect tissue stem cells and TACs; so far, these concepts have been explored mostly for the intestine.26 In irradiation-induced injury, both innate immune populations (myeloid and innate lymphoid cells [ILCs]) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) provide one tier of protection for intestinal stem cells (ISCs).11 For example, tissue recruitment of myeloid cells that secrete IL-23 triggers local RORγt+ ILC3 populations to generate local IL-22, which then acts directly on ISCs or TACs to prevent apoptosis via a STAT3-dependent mechanism.27 In addition, GATA3+ ILC2 populations produce IL-13, which maintains ISC survival via a FOXP1-β-catenin–dependent pathway28 and promotes goblet cell differentiation.29 Tregs also secrete trophic factors (eg, IL-10) that promote ISC expansion, while countering stem cell exhaustion from excessive differentiation.30 These normally protective immune populations are either outcompeted or depleted during GVHD, as manifested by the absence of ILCs27,31 and the relative deficiency of regulatory T cells (Tregs) within affected tissues.

The reaction of the intestinal epithelial compartment to immune injury has an important role in shaping the trajectory of GVHD. Although cause and effect are difficult to distinguish in vivo, T-cell reactivity in intestinal organoid cultures in vitro enriches for short-lived progeny and sculpts the repertoire of differentiated cells that emerge. In the case of T helper 17 (Th17) cells, the shift is heavily toward enterocyte differentiation with loss of more specialized populations.30

This process of immune editing and loss of specialized intestinal cell populations deprives ISCs of important niche-supporting functions. For example, loss of Paneth cells deprives the ISCs of factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor α (TGF-α), WNT3, and delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4), which are essential for their maintenance.17,33 Similarly, loss of entero-endocrine L cells depletes glucagon-like peptide 2 (GLP-2), which normally promotes the regeneration of ISCs and Paneth cells. Indeed, the GLP2 agonist teduglutide prevents apoptosis in intestinal organoids in vitro and diminishes experimental GVHD in vivo.34 Further reductions in epithelial integrity arise through the loss of the goblet cell–derived protective intraluminal mucous layer29 and through gut dysbiosis, which occurs when anti-microbial peptides derived from Paneth cells are depleted.35 GVHD also interferes with ISC-stromal interactions, by depriving stem cells of niche factors that promote their survival. For example, in the steady state, R-spondins promote self-renewal of Lgr5+ ISCs through a process that requires priming by WNT family proteins.36 In GVHD, R-spondin production from intestinal lymphatic endothelial cells is impaired,37 and exogenous replacement of R-spondin protects ISCs in experimental stem cell transplantation.16,35 Remodeling of the mesenchyme may also deprive ILC3 populations of the IL-7 required for their survival.38

Large registry studies39,40 support the concept that increasing conditioning intensity (especially through total body irradiation) is linked to higher rates of aGVHD, although randomized clinical trials comparing protocols with different cytoreductive potential have provided variable data.41 Experimentally, conditioning-induced injury lowers the threshold for the induction of aGVHD7 and also counters restoration of tissue homeostasis through several mechanisms. For example, reduced enteral nutrition in the early phase of transplantation decreases transepithelial resistance, which allows submucosal migration of bacteria (reviewed in Schörghuber and Fruhwald42). Depriving enterocytes of luminal nutrients directly blunts their metabolic activity (eg, reducing Akt phosphorylation), which leads to loss of villous structure and reduces crypt depth.43 Parenteral nutrition further promotes an imbalance between damaging (TNF-α) and protective cytokines (EGF, IL-10) leading to increased enterocyte apoptosis and impaired tight junction integrity.44-47 Although these preclinical and some correlative clinical data support the concept that enteral nutrition mitigates against GVHD,48 this question is being formally evaluated in the NEPHA randomized controlled trial, which recently completed recruitment.49

Both parenteral nutrition and use of broad-spectrum antibiotics during the neutropenic phase after transplant cause major distortions in the intestinal microflora, which reduces diversity and selects for pathogenic micro-organisms; the altered microflora can damage the protective mucus layer, create an unfavorable local metabolome, or prevent healing (reviewed extensively in Rafei and Jenq48 and Fredricks50). The precise composition of microbial-derived metabolites that favor intestinal epithelial regeneration is not fully known and is likely to be context dependent. Short-chain fatty acids are the main metabolites produced by the intestinal microbiota, and they regulate intestinal homeostasis and the immune system. For example, butyrate-producing bacteria (eg, Clostridia species) provide mature enterocytes with an essential energy source that is required for the maintenance of the villous structure and inter-epithelial cell tight junctions.51 Both the physical barrier of the villi and the active oxidation of butyrate by enterocytes reduce exposure of ISCs to butyrate at the base of the crypts, where it has a paradoxical Foxo3-dependent inhibitory effect upon proliferation.52 Thus, although exogenous butyrate has been demonstrated to prevent experimental GVHD,51 it also impairs intestinal epithelial regeneration in established experimental colitis in which villous structure has already been lost52; this latter possibility is supported by preliminary clinical data in patients with refractory intestinal GVHD in which butyrogenic bacteria are more prominent.53 A recent study in inflammatory bowel disease has suggested that antibiotic use can deplete commensal bacteria (eg, Akkermansia mucophilia54) that normally colonize intestinal ulcers and promote wound healing; instead, ulcers were colonized by the yeast Debaryomyces hansenii, which promotes a macrophage type I interferon response that directly antagonizes re-epithelialization.55

Therapies used to arrest the inflammatory response may also have an unintended adverse impact on healing. Although glucocorticoids can protect against epithelial injury by inhibiting TNF-α–induced necroptosis56 and promoting tight junction integrity,57 they also impair the generation of IL-22 by ILC358 and decrease epithelial proliferation and migration.59 Long-term use of topical corticosteroids induces skin atrophy and delayed wound healing by inhibiting keratinocyte proliferation, a process that may be underpinned by corticosteroid-induced loss of Lgr5+ hair follicle stem cell.15 In contrast, the benefit of ruxolitinib in glucocorticoid-resistant aGVHD may derive from its better preservation of adult stem cells in the skin15 and gut,60 the latter effect through direct prevention of JAK1-dependent ISC apoptosis.60 The capacity of other immune suppressive drugs to regulate epithelial regeneration in GVHD has not been addressed, but it is likely to be complex. For example, NFAT (targeted by calcineurin inhibitors) and mTORC1 (targeted by rapamycin) seem to have opposing effects on telogen-to-anagen transition of the hair follicle.61,62 Furthermore, although adult stem cells require restrained mTORC1 activity to maintain the capacity for self-renewal and differentiation in the gut, progenitor cells elevate mTORC1 activity to support their expansion and differentiation.63

Stromal GVHD

After acute injury, the specialized stroma of the thymus,64,65 lymph node,66 and bone marrow67 is normally capable of rapid regeneration in younger individuals. The recovery process at each site involves an intricate dialog between stromal precursors and cells derived from bone marrow.64-67 In irradiation-induced thymic injury, a complex array of trophic factors produced by thymic endothelia (BMP-468), ILC3 (IL-22,69 receptor activator of NF-κΒ ligand69,70), and thymocytes (keratinocyte growth factor [KGF],71 lymphotoxin72) coalesce in driving Foxn1 upregulation in thymic epithelial precursors,64 thus promoting their proliferation and restoration of the damaged epithelial structure (Figure 1C-D). In the bone marrow, irradiation triggers a transient reduction in stromal population complexity,73 whereas stroma that support the hematopoietic stem cell niche are preserved through interactions with resident immune cells (macrophages74 and Tregs75) and cross-talk with incoming hematopoietic progenitors.76 In a process that mirrors the development of the lymph node analgen, regeneration of lymph node structure after hypoxia or infection requires cooperation between IL-7+ stroma77 and lymphotoxin+ ILC3-like lymphoid tissue inducer cells.78 These regenerative programs are impeded by GVHD as manifested by permanent derangement of lymphoid organ stromal architecture, for example, in the loss of medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs),79 lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs),80,81 and bone marrow perisinusoidal mesenchymal stromal cells82 and osteoblasts.83 In thymic GVHD, recovery of thymic epithelia is impaired by parallel loss of host-derived intrathymic ILC3 populations, which leads to depletion of the IL-22 normally required for stromal regeneration.84 Physiological, age-related degeneration of the thymic stroma (eg, reduced Foxn1 expression in aged TECs85), may increase sensitivity to immune injury and explain the poor recovery of thymic function in older patients who develop aGVHD.86 In other lymphoid organs, the mechanisms that underpin regenerative failure remain unclear. For example, although depletion of host ILC3-like lymphoid tissue inducer cells also occurs in lymph node GVHD, this population is redundant in protecting the FRC network from alloimmune injury.80 Thus, there is an important need to systematically interrogate how stromal progenitors and other interacting cell populations are affected by GVHD. Extrapolation to the human setting will also require an evaluation of the impact of drugs routinely used in transplantation, such as calcineurin inhibitors and glucocorticoids that deplete mTECs87 and CD4+ T-cell immunodepletion, which impairs the FRC network integrity.88

Maladaptive repair in cGVHD

In most patients, chronic GVHD (cGVHD) emerges after previous development of aGVHD,2 an observation consistent with a model in which early injury is critical to the subsequent development of fibrosis. After wounding, monocytes recruited from the circulation and tissue-resident macrophages play critical roles in the transition from acute inflammation toward a pro-resolution tissue repair mode.89 In this tightly regulated process, timely reimposition of the anti-inflammatory epigenetic programs of tissue-resident macrophages (including those derived from differentiating monocytes) normally enables restoration of tissue integrity while limiting fibroblasia and scarring90 (Figure 1E-F). In preclinical models of sclerodermatous GVHD91-93 and bronchiolitis obliterans,94 this reset does not occur. Instead, local pro-inflammatory cell circuits imprint a pathogenic differentiation program upon incoming monocytes that leads to macrophage accumulation and remodeling of the mesenchyme and extracellular matrix toward a fibrotic trajectory.95 Although the phenotype of fibrogenic macrophages in GVHD conforms to alternatively activated M2-like cells,91 data from other models of fibrosis suggest that such populations are likely to be heterogeneous, with different roles according to location, cell–cell interactions, and time from insult.90,96 Via generation of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), profibrogenic macrophages have the potential to induce myofibroblast differentiation from multiple cell types (eg, from tissue fibroblasts or pericytes or through epithelial-to-mesenchymal or endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition).96 In skin and ocular cGVHD, the increased expression of the pro-collagen chaperone heat shock protein 47 (Hsp47) is a targetable molecular marker of pathogenic myofibroblast differentiation.93,97 profibrogenic transcriptional programs in myofibroblasts are reinforced by extracellular matrix mechanical cues that trigger integrin-mediated activation of latent TGF-β198 or by cell-cell interactions involving developmental morphogens such as those involved in WNT activation.99 Dynamic models of tissue fibrosis suggest that rapid increases in macrophage and myofibroblast frequencies positively reinforce each other, reaching an early tipping point that antagonizes return to the steady state.100 The failure of this macrophage-myofibroblast cell circuit feed-forward loop to dissipate is complex, but the major amplifiers in murine models are pro-inflammatory Th17-lineage cells that through secretion of CSF-1 drive monocyte recruitment from the circulation.91 Further amplification of this circuit may also be mediated by other cells and cytokines, for example by the in situ effects of IL-21 produced by follicular helper T cell.92 By promoting abnormal germinal center formation,101 follicular helper T cell may also drive auto- or allo-immunoglobulin G antibody formation and accelerate the fibrotic process through Fc receptor-mediated macrophage activation.95

Novel therapeutics directed at tissue repair and regeneration

Most current and investigational treatments for GVHD focus on interrupting inflammatory pathways, but their major disadvantage is that they also exacerbate immune deficiency. Alternative strategies that instead promote tissue tolerance through regeneration and repair are therefore attractive (summarized in Table 1). However, there are several challenges to be overcome before the preclinical findings can be readily translated to the clinic. First, precise upregulation of regeneration and repair pathways may be difficult because of significant overlap with those involved in resolving and/or amplifying inflammation. For example, although IL-22 has epithelial protective effects,27,69 IL-22 produced by pro-inflammatory donor Th22 and Tc22 cells have deleterious effects in the intestine102 and skin.103 Second, some of the key players involved in regeneration and repair have divergent effects according to their spatial (eg, macrophages90) or their temporal context (eg, TGF-β1, protective in early GVHD104). Third, on-target toxicities are likely to be important, for example because myofibroblast-targeted therapies may also impair normal wound healing.105 Finally, the complexity and redundancy of certain pathways (eg, Wnt-Frizzled-β-catenin) has previously been a disincentive to pursuing a targeting strategy by the biopharmaceutical sector, although this pinch point may be changing with better molecular resolution of their actions and regulation.106

Conclusion

There is an important need to address in more detail how GVHD affects tissue regeneration and repair. In particular, preclinical modeling should seek to separate the direct effects of immune injury from mechanisms that underpin tissue tolerance , including the capacity for tissues to recover when the initial immune insult is arrested. These data will provide new information regarding the regenerative and repair gap to be addressed by less immune suppressive interventions. In the clinic, novel targets could be prioritized through cross-disciplinary interactions with other fields in which disruption to regenerative or repair programs share common cellular and molecular mechanisms (which would allow testing in bucket trials, such as trials in systemic sclerosis in which a huge panoply of investigational drugs is being tested105). Adaptive trial designs that focus on common cellular and molecular mechanisms that incorporate surrogate biological end points to allow rapid selection of novel therapies could greatly accelerate advances in this area.

Authorship

Contribution: R.C. and T.T. conceived and co-wrote the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.C. received speaking honoraria from Neovii and Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals (Therakos) and received consultancy fees from Novartis. T.T. has received personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Takeda, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, grants from Chugai, Sanofi, Astellas, Teijin Pharma, Fuji Pharma, and Nippon Shinyaku, grants and personal fees from Kyowa Kirin, grants and personal fees and non-financial support from Novartis, and non-financial support from Janssen.

Correspondence: Ronjon Chakraverty, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; e-mail: ronjon.chakraverty@ndcls.ox.ac.uk.