Abstract

The primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders are a family of extranodal lymphoid neoplasms that arise from mature postthymic T cells and localize to the skin. Current classification systems recognize lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and borderline cases. In the majority of patients, the prognosis of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders is excellent; however, relapses are common, and complete cures are rare. Skin-directed and systemic therapies are used as monotherapy or in combination to achieve the best disease control and minimize overall toxicity. We discuss 3 distinct presentations of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder and present recommendations for a multidisciplinary team approach to diagnosis, evaluation, and management of these conditions in keeping with existing consensus guidelines.

Introduction

The primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) are a group of generally indolent-behaving, primary cutaneous lymphomas that include lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (pcALCL), and “borderline cases,” a classification that acknowledges overlap between these entities.1 As a group, the CD30+ LPDs account for ∼10% of cutaneous lymphomas per Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program data2 and 25% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs).1

In addition to LyP and pcALCL, the differential diagnosis for the CD30+ LPDs includes secondary cutaneous dissemination of systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and CD30+ large-cell transformed (LCT) mycosis fungoides (MF). There is substantial intersection between the CD30+ LPDs and CD30+ LCT-MF, all of which can show nearly identical clinical and histopathologic findings (particularly when the majority of tumor cells express CD30). Further, patients can exhibit multiple cutaneous CD30+ diagnoses concurrently or at different times.

The diagnosis of any CD30+ LPD is made by skin biopsy, either excisional or incisional (utilizing a punch biopsy of ≥4 mm in size).3 Biopsy specimens should be reviewed by an expert dermatopathologist or hematopathologist experienced in diagnosing cutaneous lymphomas.3 In the skin, the presence of CD30+ T cells is not specific to CD30+ LPDs; CD30 staining can be seen in a myriad of diagnoses from insect bites to drug eruptions.4 For this reason, the initial evaluation of a patient with suspected CD30+ LPD requires careful clinicopathologic correlation. Further evaluation and management of a patient with CD30+ LPD depends greatly on the subtype of LPD. In patients with suspected pcALCL, systemic disease must be excluded by imaging (ie, positron emission tomography/computed tomography [CT] scans).

We present 3 patients referred to our multidisciplinary Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic, review the existing data on CD30+ LPDs, and illustrate how we diagnose and manage these patients.

Cases

Patient 1: LyP

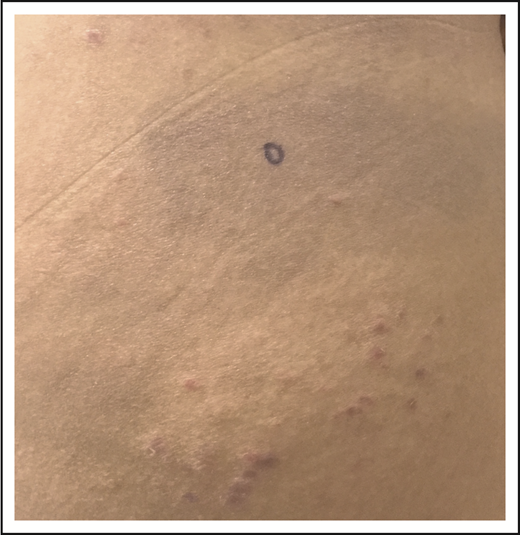

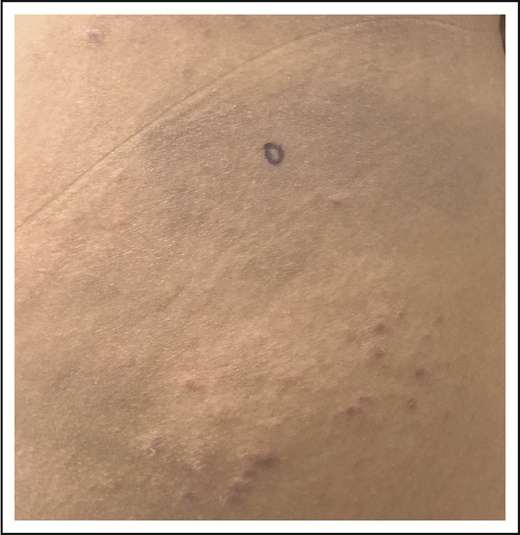

A 32-year-old woman presented with an 8-year history of “rash.” She described intermittent crops of pruritic, raised, red papules that occur in clusters on her extremities and trunk (Figure 1). She did not associate these eruptions with specific exposures. The papules would resolve after 1 or 2 months without therapy, often leaving small scars. She otherwise felt well and denied any recent medication exposures or B-type symptoms.

LyP. Erythematous papules in various stages of healing, with evidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and early scarring.

LyP. Erythematous papules in various stages of healing, with evidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and early scarring.

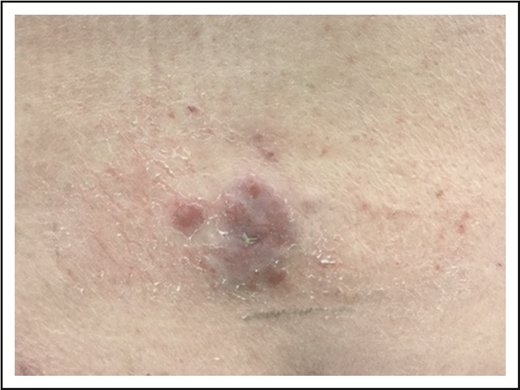

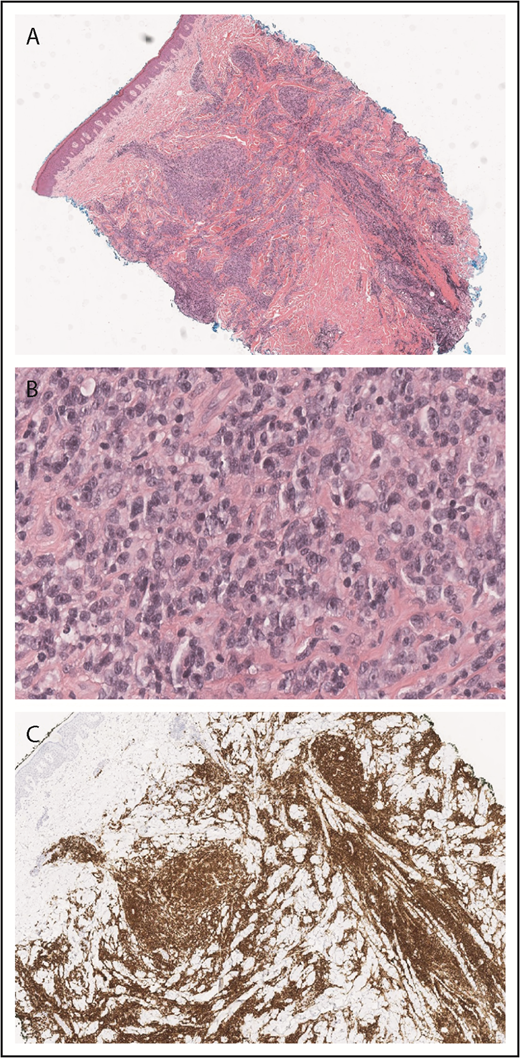

A skin punch biopsy demonstrated a dense superficial and deep infiltrate of large, atypical lymphocytes with abundant cytoplasm and frequent mitoses admixed with smaller, reactive-appearing lymphocytes (Figure 2A-B). Immunohistochemical studies confirmed that the atypical lymphocytes were CD2+, CD3+ T cells with an elevated CD4 to CD8 ratio and loss of CD7 and were positive for CD30 (Figure 2C). The histologic differential diagnosis included the CD30+ LPDs cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, LyP, or CD30+ LCT-MF. Given the clinical appearance and history of intermittent eruptions with spontaneous resolution, the patient was diagnosed with LyP (type A).

LyP histopathology. Wedge-shaped infiltrate of atypical, large lymphocytes admixed with reactive lymphocytes (A, hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], original magnification ×2; B, H&E, original magnification ×40). The atypical cells are strongly CD30+ (C, original magnification ×2).

LyP histopathology. Wedge-shaped infiltrate of atypical, large lymphocytes admixed with reactive lymphocytes (A, hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], original magnification ×2; B, H&E, original magnification ×40). The atypical cells are strongly CD30+ (C, original magnification ×2).

With the frequency of her eruption and scarring she was experiencing, the patient was interested in treatment. After basic laboratory studies were performed and showed normal metabolic and hematologic values, with negative QuantiFERON gold and urine pregnancy test results, she was started on oral methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg orally once weekly. After 2 months, she had improvement, but not complete clearing, of her eruption. Methotrexate was increased to 20 mg orally weekly, with near resolution of her eruption, and she was maintained on this dose with periodic monitoring of liver function studies and blood counts.

Clinical presentation and histopathology

The term lymphomatoid papulosis was first coined in 1968 by Dr. Warren Macaulay, describing patients with skin disorders that were somewhere in between benign dermatoses (such as pityriasis lichenoides) and clear-cut cutaneous lymphomas.5 Such patients led to confusion among treating physicians and continuous debate regarding the malignant vs benign nature of this entity. The designation LyP was proposed to emphasize the unique nature of this disorder, with its “contradiction of clinical and histological findings.”6

We now know LyP as a chronic, benign-behaving LPD in which patients experience recurring outbreaks of self-resolving papules that sometimes ulcerate or become necrotic.1 Patients describe crops of a few to hundreds of papules that come and go, lasting for 2 to 8 weeks, and resolving without any treatment, often leaving behind postinflammatory pigmentary change or scars (Figure 1). LyP can continue with this waxing and waning course for months to decades before remitting. Any age can be affected, including children,7 though the incidence of LyP overall increases with age.2 Men are affected more frequently than women.2 Involvement of locoregional lymph nodes can very rarely occur but may spontaneously resolve without treatment.8 Transformation into clinically more aggressive lymphoma or clinically relevant extracutaneous disease does not occur.

LyP has protean findings on histopathology, leading to the division of LyP into at least 6 distinct histologic subtypes: types A to E and a newly recognized subtype with the DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangment.9 The most common subtype is “classic” or type A LyP, which shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate with clusters of large, atypical CD30+ lymphocytes that are sometimes bizarre and Reed-Sternberg-like, admixed with an inflammatory infiltrate of reactive lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils. The reactive infiltrate can be so dense as to obscure the lesional cells, occasionally making recognition of the atypical cells challenging. Type B LyP closely resembles MF, with an epidermotropic infiltrate of CD30− CD4+ T cells, and type C LyP resembles pcALCL, with sheet-like growth of the large atypical CD30+ T cells. Type D LyP is a CD8+ variant that closely mimics CD8+ MF or primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma,10 particularly when there is low CD30 expression.11 In addition to the CD8+ variant, LyP can exhibit a wide variety of immunoprofiles, including expression of other cytotoxic markers like TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin,12 as well as CD5613 and T cell receptor γ,14 all without any difference in clinical behavior. A definitive histologic diagnose of LyP is not possible without (at a minimum) good clinical history, and all pathology reports of LyP (and CD30+ LPDs, for that matter) should be subject to a healthy dose of skepticism until the patient is evaluated in a specialized center with expertise in diagnosing and treating CTCL.

Molecular studies detect a T-cell clone in a proportion of LyP, with estimates ranging from 22% to 100%.15 It should be emphasized that the presence of a T-cell clone is not required for the diagnosis of LyP, nor does the absence of a clone exclude the diagnosis of LyP.

Evaluation and management

In addition to history, physical examination (including a thorough skin examination), and skin biopsy, evaluation of a patient with suspected LyP mandates only basic laboratory studies (blood cell count with differential (complete blood count [CBC]), blood chemistries (comprehensive metabolic panel [CMP]), and lactate dehydrogenase [LDH]). Consensus recommendations from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), International Society of Cutaneous Lymphoma (ISCL), and United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium (USCLC) state that imaging or bone marrow examination is not indicated in patients with suspected LyP, presuming a typical clinical presentation and otherwise normal laboratory studies. If there is any suggestion of extracutaneous disease, however, imaging is suggested.3 The ISCL/EORTC proposed a tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification of cutaneous lymphoma other than MF/Sézary syndrome (SS) (Table 1) that theoretically applies to patients with LyP; however, in routine clinical practice, patients with LyP are not usually designated a stage, as there is no difference in clinical outcome between having a single lesion or multiple lesions or involvement of a single surface area or multiple body surface areas, and visceral involvement does not occur. Routine assessment of peripheral blood flow cytometry or T-cell clonality is not warranted at the time of initial workup or subsequent monitoring. If peripheral blood involvement is found, however, an alternative diagnosis should be considered.

The differential diagnosis for LyP is broad, and patients are commonly diagnosed with alternative skin disorders prior to accurate diagnosis. Common clinical mimics include folliculitis, acne, skin picking, and drug eruption.16 Conversely, other benign skin conditions can mimic LyP clinically and histologically, including lymphomatoid contact dermatitis, insect bites or infestation, and cutaneous viral infections such as molluscum contagiosum, all of which can show significant numbers of CD30+ atypical cells (see Guitart and Querfeld4 ).

Prognosis

The 5-year survival with LyP is 100%.8 It is important to note, however, that a proportion of patients develop an associated secondary lymphoma before, concurrently, or after their diagnosis of LyP. Estimates of the incidence of a secondary lymphoma vary widely (see Kempf17 for review), but most note an incidence of secondary lymphoma in 4% to 25% of patients with LyP.3 The most common lymphomas occurring in association with LyP are other CTCLs, primarily MF, followed by ALCL (primary cutaneous and systemic) and then Hodgkin lymphoma,17 with matching T-cell clones often found across these diagnoses when patients have >1 diagnosis concurrently, suggesting divergent clonal evolution. Accurate classification of patients with multiple concurrent cutaneous lymphomas can be very challenging.

The most common modalities used to treat LyP include topical corticosteroids, phototherapy, and oral methotrexate (Table 2). Often the first question when considering the treatment of LyP, however, is whether treatment is necessary at all. Acknowledging that data are lacking, consensus guidelines support the “wait and see” strategy for the management of LyP, as none of the current treatments have curative potential or appear to impact the risk of secondary lymphoma.3

Treatment may be desired for LyP, however, because of symptoms (such as pruritus) or because of the appearance or disruption of the skin barrier (Figure 3). Topical corticosteroids are used either alone or in combination with other therapies. The rate of complete resolution of LyP with topical steroids is low at ∼12%,3 though many patients experience a partial response, and in our experience, this approach can be particularly helpful for managing pruritus. Phototherapy (narrowband UVB [NB-UVB] or psoralen plus UVA [PUVA]) is also used for the treatment of LyP, with pooled data suggesting complete response rates of 26% and partial response rates of 68% for PUVA-treated patients.3

Necrotic LyP. Extensive coalescing papules with overlying hemorrhagic crust.

Low-dose methotrexate is perhaps the best-documented systemic treatment of LyP, with the largest series by Vonderheid et al18 showing that the majority of patients either had complete resolution of lesions or significant decrease in new lesions during methotrexate therapy (subcutaneous administration). Two more recent series reported on 54 and 47 patients (respectively) with LyP treated with methotrexate, with a dose range of 2.5 to 37.5 mg weekly. Complete response rates in these series ranged from 20% to 52%, and partial responses were common.19,20 When used for LyP, methotrexate is taken orally or administered subcutaneously every 1 to 4 weeks; maintenance is usually required, as recurrences off therapy are common.19,21 Responses of LyP to methotrexate are often rapid, with resolution within 1 to 2 weekly doses. We typically start at 10 to 15 mg by mouth weekly, increasing by 2.5 to 5 mg every few weeks until there is complete resolution. Once there has been a disease-free period of at least several months, attempts can be made at weaning down methotrexate to the lowest effective dose, though patients are rarely able to taper completely off without recurrent LyP and may be methotrexate dependent.22

Brentuximab vedotin (BV) is a fully humanized, immunoglobulin G1a, monoclonal CD30-targeted antibody conjugated with the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin E and has been used to treat LyP.20,23 BV is exceedingly rarely (if ever) required for LyP. Weighing a high (67%) incidence of peripheral neuropathy from BV23 with the benign nature of LyP, we conclude that BV should only be used to in exceptional cases of LyP, after failure of other first-line agents.

Patient 1, continued

After managing her LyP with oral methotrexate (20 mg weekly) for several years with a partial remission that was satisfactory to the patient, she developed thin, erythematous patches on her lateral thighs and buttocks (Figure 4). Although numerous skin biopsies performed over several months were not unequivocally diagnostic, the patient was presumed to have developed MF in association with LyP. NB-UVB was added to her methotrexate with resolution of her patches and improved control of her LyP lesions, and she continues on oral methotrexate with intermittent courses of NB-UVB.

LyP and mycosis fungoides. Thin erythematous patches of MF that are distinct from the concurrent erythematous papules of LyP.

LyP and mycosis fungoides. Thin erythematous patches of MF that are distinct from the concurrent erythematous papules of LyP.

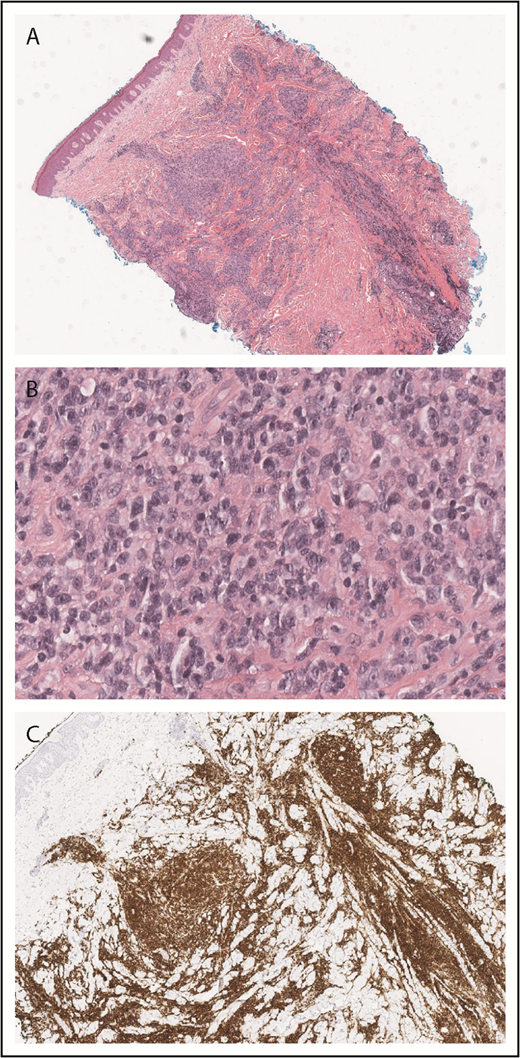

Patient 2: localized pcALCL

A 79-year-old well-appearing man presented with an asymptomatic, eroded plaque on the low back (Figure 5) that had been present for 3 months and initially thought to be a spider bite. Around the same time, he also had some “pimples” or “bug bites” on his shoulders and arm, which had self-resolved by the time of his evaluation. The lesion on his back did not, however, and he presented to a dermatologist and underwent skin biopsy. The skin biopsy showed a dense dermal proliferation of large, atypical CD3+ T cells with marked nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 6A-B). The atypical cells were CD8+, CD4−, with partial loss of CD5 and CD7, and strong CD30 expression (Figure 6C). Ki-67 showed an increased proliferative rate of 50% to 75%. In situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus was negative, as was anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) staining. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies were not performed.

PCALCL. An ulcerated plaque on the low back. Note incidental overlying dermatitis from adhesive bandages.

PCALCL. An ulcerated plaque on the low back. Note incidental overlying dermatitis from adhesive bandages.

PCALCL histopathology. Diffuse dermal infiltrate of large, atypical lymphoid cells that are CD30 positive (A, H&E original magnification ×2; B, original magnification ×40; C, CD30, original magnification ×4).

PCALCL histopathology. Diffuse dermal infiltrate of large, atypical lymphoid cells that are CD30 positive (A, H&E original magnification ×2; B, original magnification ×40; C, CD30, original magnification ×4).

The patient otherwise felt well, with no B-symptoms or self-reported lymphadenopathy. The diagnosis of pcALCL was suspected. The patient had basic laboratory studies (CBC, CMP, and LDH) and underwent CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis that together showed no evidence of systemic involvement. He was diagnosed with pcALCL, stage I (T1a, N0, M0). Radiation therapy was recommended, and the patient received a total of 25 Gy with complete resolution of the plaque. No further skin lesions have developed in the subsequent 2 years.

Clinical presentation and histopathology

Our patient illustrates the most typical clinical presentation of pcALCL, with a single ulcerated nodule or tumor. Only 20% of patients with pcALCL have multiple or disseminated lesions (Figure 7).8 The median age at diagnosis of pcALCL is 60 years; unlike LyP, pcALCL is very rare in children.8 Males are more frequently affected than females (2-3:1).1 Any region of the skin can be affected by pcALCL, including mucosal surfaces.24 pcALCL remains limited to the skin in the majority of patients, with only 10% developing involvement of regional lymph nodes1 ; extensive nodal involvement and visceral disease occurs in ∼7% of patients.25 As with other CD30+ LPDs, pcALCL can spontaneously regress at a rate of ∼20% to 44%.8,26 Relapses are frequent, occurring in ∼40% of patients8,25 ; the overall prognosis remains excellent even after relapse. Like those with LyP, patients with pcALCL have a higher incidence of secondary hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly MF.

Confirming the diagnosis of pcALCL requires the exclusion of systemic ALCL as well as MF. Evaluation of patients with suspected pcALCL should include a detailed history emphasizing any prior diagnosis of systemic ALCL, MF, or LyP and a thorough skin and lymph node examination. Recommended laboratory evaluation includes CBC, CMP, and LDH. Imaging (CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with or without the neck if head and neck involvement is present or positron emission tomography/CT) should be performed in all patients at the time of diagnosis to exclude systemic ALCL. This is of particular importance if there is mucosal involvement, as a substantial portion of these patients will have systemic ALCL.24 Clinically or radiologically suspicious lymph nodes should be assessed by excisional biopsy whenever possible.3 Bone marrow examination has limited value in the diagnosis of pcALCL, and consensus recommendations suggest reserving the procedure for those with multifocal tumors27 or unexplained abnormal hematological results or when there is certain extracutaneous involvement by any ALCL.3

Typical histopathologic findings in pcALCL are of a nodular or diffuse infiltrate of large, atypical lymphocytes with anaplastic morphology, often extending into the subcutaneous fat. Epidermotropism (epidermal involvement) is not typically seen, in contrast to CD30+ LCT MF. Histologic variants with immunoblastic (nonanaplastic) morphology28 and spindled-cell morphology29 have been described. Other histologic findings common in pcALCL include abundant neutrophils or eosinophils, keratoacanthoma-like changes,30 angiocentricity,31 and dermal lymphatic involvement.32 The malignant T cells in pcALCL are generally CD4+, CD8−, with variable loss of the pan T-cell markers CD2, CD3, and CD5 and frequent coexpression of cytotoxic markers such as TIA-1 and perforin.33 A minority (5%) of cases are CD8 predominant,1 as in our patient. By definition, CD30 demonstrates >75% staining in the majority of tumor cells.34 A “null” variant (non-B or T cell) has historically been described; however, many of these cases may be T cell in origin when assessed for T-cell receptor gene rearrangement.28,35 CD15 is negative.1

Most pcALCL express cutaneous lymphocyte antigen but are usually negative for epithelial membrane antigen and ALK, in contrast to systemic ALCL.36-38 There are exceptions, however, with some cases of pcALCL reported with epithelial membrane antigen and/or ALK expression.38,39 Immunohistochemistry should never be depended upon to definitively differentiate pcALCL from systemic ALCL, as there is no reliable histologic way to differentiate pcALCL from ALK-negative systemic ALCL involving the skin. While ALK expression is unusual in pcALCL, the associated t(2;5) translocation can occasionally be detected in a minority of pcALCL cases and thus lacks specificity for differentiating pcALCL from systemic ALCL.38,40,41

The majority of cases of pcALCL demonstrate monoclonal rearrangements of the T-cell receptor gene.42 Numerous chromosomal aberrations are found in pcALCL, including genomic imbalances that lead to copy-number gains of known oncogenes.43 Multiple myeloma oncogene-1/interferon regulatory factor-4 (MUM-1/IRF4) is a transcription factor expressed in plasma cells, some B cells, and activated T cells. Overexpression of IRF4 protects CD4+ T cells against apoptosis, providing a potential mechanism for lymphomagenesis.44 A proportion (∼28%) of pcALCLs demonstrate DUSP22 (MUM1/IRF4 translocations.45,46 Immunostaining for MUM-1 is neither a specific nor reliable marker for differentiating the CD30+ LPD, as MUM-1 expression is frequently found in all types of ALCL.47,48 TP63 translocations can very rarely be found in pcALCL.49 Gene expression profiling of pcALCL demonstrates increased expression of the skin-homing chemokine genes CCR10 and CCR8, which may in part explain the tendency of pcALCL to remain in the skin.50

The Ann Arbor staging system categorizes patients with multifocal pcALCL as stage IV,51 which misleadingly implies much more aggressive behavior. To address this discrepancy, the TNM staging system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and SS proposed by the ISCL and EORTC should be used (Table 1). This staging system has clinical validity in pcALCL, with patients with T3 disease faring worse than those with T1 or T2 involvement.25

pcALCL has a generally excellent prognosis, with a disease-specific 10-year survival of >90%.1 Limited involvement of locoregional lymph nodes does not significantly impact prognosis.8 A notable exception to the generally good prognosis is patients with extensive regional single limb disease (see case 3 in this article).25,26,52,53 Other factors that may unfavorably impact prognosis include older age, lack of spontaneous remission, occurrence on the leg, generalized (T3) skin involvement,25,27,28 and pcALCL occurring in the setting of solid organ transplant.54

Management

Localized treatment, either with radiotherapy (RT) or surgical excision, is preferred therapy for single or localized pcALCL. Single- or multiagent chemotherapy should generally be avoided in these patients, given the excellent overall prognosis and excessive toxicities associated with cytotoxic agents3 (Table 3). An exception is pcALCL with regional lymph node involvement; in this scenario, BV is the preferred initial therapy, while other modalities, including methotrexate, pralatrexate, multiagent chemotherapy, and RT, are alternatives.55 RT has demonstrated response rates (RRs) comparable or better than systemic chemotherapy, but with more durability.53,56 In a multicenter retrospective study, the overall RR (ORR) to RT was 100%, with complete clinical response in 95%. Despite high RR, relapse rates in pcALCL treated with RT are high (estimated at 41%).3 The optimal dose of RT is not currently known; National Cancer Center Network guidelines suggest 30 to 36 Gy, but doses of <30 Gy may also be effective,57 as in our patient. Consensus guidelines on field and dose for RT of pcALCL from the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group are available.58

Surgical excision is also a commonly used treatment of pcALCL, particularly when excisional biopsy is performed for diagnosis. As with most therapies of pcALCL, relapse rates are high (43%).3

EORTC/ISCL/USCLC guidelines, acknowledging a lack of published evidence, recommend that low-dose (5-25 mg), single-agent methotrexate is also an option preferred over multiagent chemotherapy for pcALCL given the superior safety and “general expert consensus that its use is reasonable.”3,8,59

Several immunomodulating agents have been used in individual reports and case series of patients with pcALCL. Bexarotene is a synthetic retinoid that selectively activates the RXR subfamily of receptors and is approved for refractory CTCL.60 Bexarotene has been used successfully in limited reports in combination with extracorporeal photopheresis61 and interferon alfa62 for treating pcALCL. Thalidomide was effective in 2 reported pcALCL patients and may exert effects via NF-κB inhibition.63 Imiquimod is a topical Toll-like receptor-7 agonist that induces local cytokine release and has been used successfully in a few cases of localized pcALCL.64,65

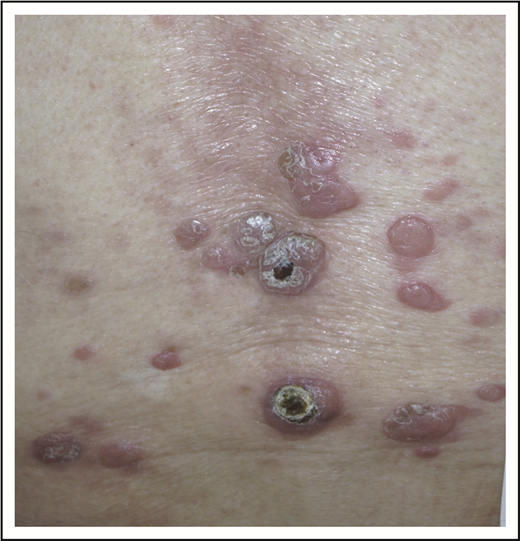

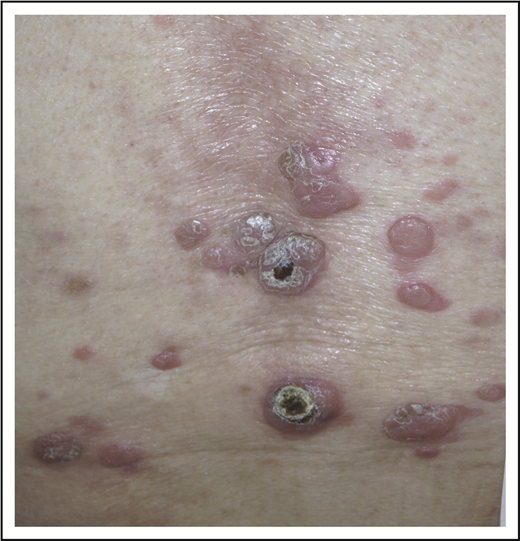

Patient 3: widespread cutaneous ALCL

A 62-year-old woman with no prior history of skin disorders presented with a 6-month history of rapidly progressive, ulcerated nodules, and tumors on the left leg. She described noted multiple papules that arose simultaneously, coalescing into a large, painful, ulcerated plaque (Figure 8). She otherwise felt well, without fevers, sweats, or weight loss. A skin biopsy specimen demonstrated a sheet-like proliferation of large, atypical lymphoid cells in the mid to deep dermis with prominent nucleoli, clumped chromatin, and increased amphophilic cytoplasm. There were abundant admixed neutrophils. Immunohistochemistry showed that the neoplastic cells were CD3+, CD4+, CD8− T cells with loss of CD5 and CD7 and uniform strong CD30. TIA-1 was weakly positive, and CD56 and ALK were negative. The Ki-67–defined proliferative rate was elevated.

Laboratory studies showed an elevated white blood cell count of 18.5 × 109/L but otherwise normal blood counts and differential. CMP was normal, as was LDH. The patient underwent CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, demonstrating ipsilateral regional lymphadenopathy highly suspicious for lymphomatous involvement. There were no other enlarged abdominal or otherwise pelvic lymph nodes or evidence of splenic or extralymphatic organ involvement.

Clinical presentation and histopathology

This patient demonstrates a more complex scenario, with numerous, advanced cutaneous ALCL lesions with probable regional lymph node involvement, raising consideration for pcALCL with regional lymph node involvement (which we favored) vs localized, systemic ALK-negative ALCL with skin involvement. In either case, standard, localized therapy was not feasible. Several studies have demonstrated that patients with pcALCL with extensive limb disease (ELD), particularly when involving the lower limb, have worse outcomes compared with limited pcALCL.52 The prognosis of pcALCL with ELD is worse than if extracutaneous disease is present.53 The reason for this worse prognosis with ELD is not fully understood. ELD demonstrates a unique gene expression profile, with upregulation of IL2R and STAT5, which may play a role in T-cell activation.53

Management

There is currently no standard-of-care recommended treatment of widespread or multifocal pcALCL. Patients with multifocal or ELD pcALCL have lower response rates to traditional therapy compared with localized pcALCL.53 Multiagent chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone has been most frequently used, with a high ORR of 85%, but with frequent and rapid relapses.3,8,53 Alternative regimens described in individual cases or small case series include cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone and etoposide, mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, and bleomycin.53,66 Monotherapy regimens utilizing oral etoposide, gemcitabine, and low-dose methotrexate have also been tried, but data are lacking.53,59,67

BV demonstrated an ORR of 75%, with time to response of ∼3 weeks in a phase 2 prospective trial in CD30+ cutaneous lymphomas.23 BV was well tolerated, with the most common nonhematologic toxicity being peripheral sensory neuropathy, observed in 65%. High activity of BV in CD30+ CTCL was further confirmed in the phase 3 randomized, prospective ALCANZA trial.68 When compared with patients treated in the control arm, treatment with BV was associated with superior ORR and PFS. Experience with BV in patients with locally advanced pcALCL, including ELD type, is limited. Despite this, given the high activity of BV in pcALCL, BV presents an attractive single-agent option for patients who require systemic therapy.

Pralatrexate, a potent antifolate, has approval by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of relapsed and refractory PTCL based on the results of a prospective phase 2 trial (PROPEL).69 Mucositis is the main nonhematologic toxicity of pralatrexate, though mucositis is significantly lower when “cutaneous” dosing (15 mg/m2 per week) is used, and guidelines for usage of pralatrexate are strictly followed (ie, vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation).70 The largest experience with pralatrexate in patients with transformed mycosis fungoides was reported in the ad-hoc subgroup analysis, in which the authors reported an ORR of 58% (per investigator assessment) and duration of response of >4 months.71,72 Given the activity of pralatrexate in systemic ALCL and large-cell transformed MF, pralatrexate represents a reasonable therapeutic option for patients with aggressively behaving pcCD30+ LPD and CD30+ LCT MF when systemic therapy is warranted.

Patient 3, continued

Given the presence of multiple comorbidities, a standard multiagent chemotherapy regimen was thought to be unduly risky. She received 8 cycles of single-agent BV with complete resolution of cutaneous tumors (verified by histology) and lymphadenopathy but with persistent edema and ulceration (Figure 9).

Special considerations

Particularly challenging are cases of pcALCL with deep tissue extension including involvement of fat, fascia, and/or skeletal muscle. EORTC/ISCL/USCLC guidelines state that multiagent chemotherapy is not recommended as first-line therapy for pcALCL limited to the skin3,59 ; however, in the absence of reliable data, such patients should probably be approached with systemic combination chemotherapy until future studies support alternative options.

Conclusions

Overtreatment remains a frequent occurrence in managing patients with primary cutaneous CD30+ LPDs. These disorders remain incurable in the overwhelming majority of the patients but with low disease-related mortality. That means that patients may be treated over extended periods (in some cases decades) and experience numerous relapses. With this in mind, it is vital to continuously reassess the clinical benefit of any therapy, treatment-related toxicity, and impact on quality of life. We rarely employ indefinite “maintenance therapy” or use drug combinations with inherent cumulative/additive toxicity, instead preferentially using novel biologic, targeted, or immunomodulatory agents. Following the success of BV, newer agents targeting CD30 have entered clinical trials, and results of these studies are eagerly awaited. We also maintain, however, that the “financial toxicity” and clinical risk of newer agents should be taken into account in these patients with these often chronic, and sometimes minimally symptomatic, disorders.

Authorship

Contribution: M.M.S. and A.S. contributed equally to this study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.S. participated as an investigator in the PROPEL and ALCANZA clinical trials and a clinical trial of pralatrexate in mycosis fungoides. M.M.S. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michi M. Shinohara, University of Washington Dermatology and Dermatopathology, Box 356524 BB1332E, Seattle, WA 98195; e-mail: mshinoha@uw.edu.

REFERENCES

Author notes

M.M.S. and A.S. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 2. LyP histopathology. Wedge-shaped infiltrate of atypical, large lymphocytes admixed with reactive lymphocytes (A, hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], original magnification ×2; B, H&E, original magnification ×40). The atypical cells are strongly CD30+ (C, original magnification ×2).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/134/6/10.1182_blood.2019000785/3/m_bloodbld2019000785cf2.png?Expires=1769397643&Signature=cENkSB8NMS7L-E~Ow9VF4bjrhU3O-XzW20U606VIkb2NtuILq0wf9wSNEjxctdvK~P5LGDxT~yH12SkLdO-lvOz70nXIu1r9elDwjbP-bCq0joHQIpZDf4IVglGxFY8VvQtBduy8jpAPNqbAT6HHylLvqWSTSiMDTmrDrYDdDh9PKxxL0oxQqMzz-lFtvPUjJnnP6dGIQujvXJ1UheYs79uJdeWnn6cNLhRU0kWLpZzQED8do6UX6HGGd2Wkuq2r2oQ50bHeKPodnhpOz6~z-G2-29x3IreUQImlHIHllqw9ct91IVaDWdMg6wQzQ7jQYTa7FRiAdvyIDILo6hXMgQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. LyP histopathology. Wedge-shaped infiltrate of atypical, large lymphocytes admixed with reactive lymphocytes (A, hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], original magnification ×2; B, H&E, original magnification ×40). The atypical cells are strongly CD30+ (C, original magnification ×2).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/134/6/10.1182_blood.2019000785/3/m_bloodbld2019000785cf2.png?Expires=1769397644&Signature=4RHmstJStoEuzMOnLqdXKAnHTSfkQGY3fBl3EDiOWFBivq3AGIFRkYZmijA1ZkQ314p6cjfUD07ZAvVxKvOkoMrL7pGsWisvmtaBVZharHCXR6NXV7BkOb0esvscxogxw1XIf95Tw2QCtv5lyYNhmhZJ2o2Bu6q9ngBgjadKFoPDM1QOFjzuxsIl3ACiJz83eEW~onq01hjAR0FmYKeArMpt5LxLRx7s1Fq49q2NS1oIHHx4RLb5M4FzCWLR2EW1q3LaZ970tBi98LyS1SeVywAMg6cwAKLAz0O1try4cXCNm628snBaNevm1e~Qmz54XrWMcGg9A1Qzmkiuz5DxAA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)