Key Points

It has been suggested that rFVIII, which is more immunogenic than plasma-derived FVIII (pdFVIII), can be safely used in low-risk patients.

Among 235 participants in a randomized trial, genetic risk stratification did not identify a low-risk group for treatment with rFVIII.

Abstract

A recent randomized trial, the Survey of Inhibitors in Plasma-Product Exposed Toddlers (SIPPET), showed a higher risk of inhibitor development with recombinant factor VIII (rFVIII) than plasma-derived concentrates (pdFVIII). We investigated whether risk stratification by F8 mutation identifies patients who do not suffer this deleterious effect of rFVIII. Among 235 randomized patients with severe hemophilia A previously untreated with FVIII concentrate, 197 with null mutations were classified as high risk and 38 with non-null mutations were classified as low risk. With pdFVIII, no inhibitors occurred in those with low genetic risk, whereas high-risk patients had a cumulative incidence of 31%. The risk among low- and high-risk patients did not differ much when they were treated with rFVIII (43% and 47%, respectively). This implies that patients with low genetic risk suffer disproportionate harm when treated with rFVIII (risk increment 43%), as also shown by the number needed to harm with rFVIII, which was 6.3 for genetically high-risk patients and only 2.3 for low-risk patients. Risk stratification by F8 mutation does not identify patients who can be safely treated with rFVIII, as relates to immunogenicity. This trial was registered at the European Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT) as #2009-011186-88 and at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01064284.

Introduction

The development of neutralizing antibodies against factor VIII (FVIII) is a serious complication of the early stages of replacement therapy in hemophilia A. Meta-analyses of observational studies had suggested a higher risk of inhibitor development with concentrates produced by recombinant technologies (recombinant FVIII [rFVIII]) than with those derived from human plasma (plasma-derived FVIII [pdFVIII]).1,2 This was recently confirmed in a randomized trial,3 with cumulative incidences of inhibitor development of 45% for rFVIII and 27% for pdFVIII (hazard ratio [HR], 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2-3.0).

Few risk factors for inhibitor development that allow risk stratification are known. Unmodifiable risk factors are the residual FVIII concentration and genetic variation, that is, the causative F8 mutation due to secretion of some defective protein in non-null mutations, and, to a much lesser degree, variation outside of the F8 locus.4,5 Modifiable risk factors are age at first treatment and the source of FVIII concentrate.6,7 Given the particularly high risk with rFVIII, restricting the use of rFVIII to low-risk patients and treating high-risk patients with pdFVIII has been suggested.

We investigated such a risk-profiling strategy in a post hoc analysis of the Survey of Inhibitors in Plasma-Product Exposed Toddlers (SIPPET) study, in which we used the FVIII genotype (F8 mutation) to classify patients by prior risk because this strong determinant can be established prior to treatment initiation, to assess whether genetic profiling would identify patients who can be safely treated with rFVIII.

Study design

SIPPET is an open-label, international, randomized trial in which 251 previously untreated (n = 142) or minimally treated (n = 109) patients were treated exclusively with a concentrate from the class of rFVIII or pdFVIII between 2010 and 2014.3

Eligible patients were boys under 6 years of age with severe hemophilia A (FVIII:C <1 IU/dL) never exposed to FVIII concentrate, and not or minimally treated (<5 times) with blood components (eg, whole blood, fresh-frozen plasma) and negative for FVIII inhibitors at the central laboratory8 (EudraCT 2009-011186-88 and clinicaltrials.gov NCT01064284). Ethical committee approval was obtained for the SIPPET trial, including studies investigating inhibitor risk factors.

Patients were block-randomized between rFVIII and pdFVIII. The recombinant products included: Recombinate (Baxalta, Bannockburn, IL), Kogenate FS (Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany), Advate (Baxalta), and ReFacto AF (Pfizer, New York, NY). pdFVIII brands were Alphanate and Fanhdi (Grifols, Barcelona, Spain), Emoclot (Kedrion Biopharma, Lucca, Italy), and Factane (LFB, Les Ulis, France). Patients were followed for 50 consecutive exposure days or 3 years, until death, or until the development of a centrally confirmed inhibitor, whichever occurred first. An exposure day was defined as a calendar day with 1 or more infusions of FVIII.

The primary outcome was the development of an inhibitor ≥0.4 Bethesda units (BU) by the Nijmegen Bethesda assay.8 High-titer inhibitors were defined as peak levels ≥5 BU. Patients were repeatedly tested and 1 central test was performed in all patients at study completion. Positive tests were confirmed in the central laboratory in separately drawn blood.

Statistical analysis was by survival analysis with the number of exposure days as the time variable. Cumulative incidences were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, with CIs derived with the Hosmer-Lemeshow method.9 HRs were determined with Cox regression. Patients were classified as high risk when they carried a null mutation in the F8 gene and as low risk when they carried another or no causative variant. We also estimated numbers needed to harm (NNH).

Results and discussion

Among 251 patients, 125 were randomized to pdFVIII and 126 to rFVIII. In 16 patients (8 in each group, of whom 4 developed inhibitors, equally distributed over the treatment arms), DNA was unavailable, and they were excluded. Null mutations were detected in 197 patients, consisting of intron 22 inversions (n = 110), nonsense mutations (n = 34), frameshift mutations (n = 31), large deletions (n = 16), and intron 1 inversions (n = 6), whereas 38 patients had non-null mutations (missense, splice site, polymorphisms or no mutation found [n = 1]).

The type of mutation was clearly associated with inhibitor risk: among 197 patients classified as high risk, 65 developed an inhibitor (cumulative incidence, 38%; 95% CI, 31%-46%), whereas among the 38 patients classified as low risk, 7 developed an inhibitor (cumulative incidence, 24%; 95% CI, 8.2%-40%). This implied a nearly doubled rate of inhibitors in high- vs low-risk patients (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.8-3.9).

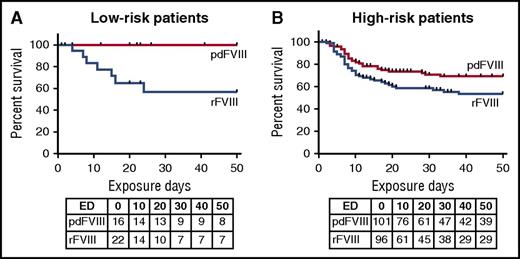

High- and low-risk patients were equally distributed over the 2 arms of the trial (Table 1). Among high-risk patients, cumulative incidence was 31% (95% CI, 22%-41%) when treated with pdFVIII, and 47% (95% CI, 36%-58%) when treated with rFVIII (risk difference, 15.8%) (Table 1). Among low-risk patients, no inhibitors developed with pdFVIII, whereas the cumulative incidence was 43% with rFVIII (95% CI, 36%-58%) (log-rank test, P = .009) (Table 1). With a within group comparison, there was a distinct difference in inhibitor frequency in low- and high-risk patients treated with pdFVIII (P = .02), whereas there was none in patients treated with rFVIII (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.53-2.66). The survival curves (Figure 1) show a low risk of inhibitors for patients with low genetic risk and treated with pdFVIII, an intermediate risk for patients with a high genetic risk profile treated with pdFVIII, and a high risk of inhibitors for patients treated with rFVIII, regardless of their genetic risk profile.

Survival by genetic risk and treatment class. Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the cumulative incidence of inhibitors in 4 groups, with low (A) and high (B) genetic risk based on the F8 mutation, treated with either pdFVIII and rFVIII. Below the curves are the number of patients at risk at the start of each 10-day exposure day (ED) interval.

Survival by genetic risk and treatment class. Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the cumulative incidence of inhibitors in 4 groups, with low (A) and high (B) genetic risk based on the F8 mutation, treated with either pdFVIII and rFVIII. Below the curves are the number of patients at risk at the start of each 10-day exposure day (ED) interval.

The risk difference can also be expressed as the number needed to treat, or NNH, which is how many extra patients will need to be treated with rFVIII rather than pdFVIII to cause 1 extra patient with an inhibitor. Overall, this was 5.6; for high-risk patients, it was 6.3 and for low-risk patients it was only 2.3.

There were 48 high-titer inhibitors: 0 of 16 low-risk patients with pdFVIII, 19 of 101 high-risk patients with pdFVIII (18.8%), 4 of 22 low-risk patients with rFVIII (18.2%), 25 of 96 high-risk patients with rFVIII (26.0%), which follows the same pattern as for all inhibitors (Table 1).

Intron 22 inversions were found in 87 patients of whom 27 developed an inhibitor. Cumulative incidence was 31% (95% CI, 18%-49%) among those treated with pdFVIII and 42% (95% CI, 28%-60%) among those treated with rFVIII. So, patients with intron 22 mutation had inhibitor development rates that appeared similar to others with null mutations.

In conclusion, we found that whereas those with non-null mutations had a lower risk than those with null mutations when treated with pdFVIII, rates were about the same when treated with rFVIII. The risk difference was greatest for those with low genetic risk because none developed an inhibitor when treated with pdFVIII and 43% when treated with rFVIII. This example of gene-environment interaction implies that genetically low-risk patients suffer disproportionate harm when treated with rFVIII, as illustrated by the NNH, which was 2.3. In other words, genetic risk profiling cannot identify patients at low risk when treated with rFVIII.

The major strength of this study was that it was randomized between rFVIII and pdFVIII, whereby confounding by indication was eliminated.3 Furthermore, inhibitor testing was performed according to a prespecified frequent protocol with central laboratory confirmation. The study is limited by a small sample size. However, differences were striking. We compared classes of rFVIII and pdFVIII, and there may be products within the classes that differ in immunogenicity. It is unlikely, however, that this would differ by F8 genetic risk.

These results lend no support for a strategy of risk profiling of previously untreated patients and prescribing rFVIII to those with a low prior risk.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the nonprofit Angelo Bianchi Bonomi Foundation and the Italian Ministry of Health (Progetti Finalizzati and Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco). Grifols, Kedrion Biopharma, and LFB provided unrestricted grants to the Angelo Bianchi Bonomi Foundation.

The funders had no involvement in study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation, and publication decision.

Authorship

Contribution: F.R.R. conceived the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; R.P. and I.G. collected data and were involved in the analysis; P.M.M. and F.P. supervised the study and critically revised the paper; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.P. has received honoraria or consultation fees from Freeline, Kedrion Biopharma, LFB, and Octapharma; has received honoraria for participating as a speaker at educational meetings organized by Ablynx, Bayer, Grifols, Novo Nordisk, and Sobi; and is also a member of Ablynx and F. Hoffmann-La Roche advisory boards. P.M.M. has received speaker fees from Alexion, Baxalta/Shire, Bayer, CSL Behring, Grifols, Kedrion, LFB, and Novo Nordisk, and is a member of Bayer and Kedrion advisory boards. R.P. has received travel support from Pfizer and Grifols. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the SIPPET Study Group appears in the online appendix.

Correspondence: Frits R. Rosendaal, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, C7-P, Leiden University Medical Center, P.O. Box 9600, NL-2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands; e-mail: f.r.rosendaal@lumc.nl.