Key Points

HSCT after PD-1 blockade is feasible, although may be associated with increased early immune toxicity.

PD-1 blockade may cause persistent depletion of PD1+ T cells and alterations in T-cell differentiation impacting subsequent treatment.

Abstract

Anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibodies are being increasingly tested in patients with advanced lymphoma. Following treatment, many of those patients are likely to be candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). However, the safety and efficacy of HSCT may be affected by prior PD-1 blockade. We conducted an international retrospective analysis of 39 patients with lymphoma who received prior treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor, at a median time of 62 days (7-260) before HSCT. After a median follow-up of 12 months, the 1-year cumulative incidences of grade 2-4 and grade 3-4 acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) were 44% and 23%, respectively, whereas the 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD was 41%. There were 4 treatment-related deaths (1 from hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, 3 from early acute GVHD). In addition, 7 patients developed a noninfectious febrile syndrome shortly after transplant requiring prolonged courses of steroids. One-year overall and progression-free survival rates were 89% (95% confidence interval [CI], 74-96) and 76% (95% CI, 56-87), respectively. One-year cumulative incidences of relapse and nonrelapse mortality were 14% (95% CI, 4-29) and 11% (95% CI, 3-23), respectively. Circulating lymphocyte subsets were analyzed in 17 patients. Compared with controls, patients previously treated with PD-1 blockade had significantly decreased PD-1+ T cells and decreased ratios of T-regulatory cells to conventional CD4 and CD8 T cells. In conclusion, HSCT after PD-1 blockade appears feasible with a low rate of relapse. However, there may be an increased risk of early immune toxicity, which could reflect long-lasting immune alterations triggered by prior PD-1 blockade.

Introduction

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) is an inhibitory receptor expressed on activated T cells and other lymphoid and myeloid cells. The PD-1 synapse is an important mechanism by which malignancies can evade the host immune response.1,2 Clinical trials of anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have demonstrated promising results in lymphoma patients with advanced disease. Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), which appears to have a unique biologic dependence on the PD-1 pathway, is particularly susceptible to PD-1 blockade,3,4 and 1 PD-1 inhibitor, nivolumab, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of classical HL.5 Clinical activity has also been observed in several subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).6,7

Given the success of these agents in early studies, anti-PD-1 mAbs are being tested alone and in combination in a growing number of clinical trials across many hematologic malignancies. Many participants in these trials will at some point become potential candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT); however, the safety and efficacy of HSCT may be different in patients previously exposed to PD-1 inhibitors, given their immunomodulatory mechanism and their prolonged clinical activity.8 Specifically, residual PD-1 inhibition peri- and post-HSCT could enhance allogeneic T-cell responses, which could augment the graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect but also increase the incidence or severity of immune complications. Animal models demonstrate that PD-1 blockade early after allogeneic HSCT may augment GVT in anatomic niches that are susceptible to relapse,9 but could also result in higher rates of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and increased GVHD lethality.10,11 Early clinical trials suggest that checkpoint blockade therapy with nivolumab or ipilimumab (IPI) as treatment of relapse after HSCT could be effective with a tolerable side-effect profile.12,13 Understanding the impact of prior PD-1 blockade on both the safety and the efficacy of HSCT is critical to select candidates for PD-1 blockade among patients who may be future candidates for HSCT and to select appropriate treatment strategies for HSCT candidates who are responding to PD-1 blockade or who have relapsed after prior PD-1 blockade.

We therefore conducted an international retrospective study of patients treated with an anti-PD1 mAb at some point prior to HSCT, with the goal of describing toxicity and disease control. In addition, immune profiling analysis using flow cytometry was performed on a subset of patients with available samples pre- and post-HSCT to explore the possible basis of observed differences in HSCT outcomes.

Methods

Patients

To develop this collaboration, we contacted centers that participated in early studies of PD-1 inhibitors for lymphoma, or that informed us of patients at their center who had been transplanted after prior PD-1 blockade. Between July 2013 and March 2016, we identified 39 patients who received pembrolizumab or nivolumab for treatment of HL or NHL and subsequently underwent allogeneic HSCT. Patients underwent transplantation under a variety of treatment plans and investigational protocols. The Institutional Review Boards at all sites approved the protocol prior to patient enrollment. A waiver of informed consent was obtained for this retrospective chart review. Medical records of all patients were reviewed by participating investigators. Assessment of GVHD was performed by each center following their standard grading practice.

Immune profiling analysis

Patients treated at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Brigham and Women's Hospital (DFCI/BWH) who had available samples pre- and post-HSCT were included in an immune reconstitution subanalysis. Patients treated at the same institution with reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) HSCT without prior anti-PD-1 treatment between 2011 and 2015 were used as a control cohort. Blood samples from both cohorts were obtained on day 0 (prior to stem cell infusion) and 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after transplant. Whenever possible, fresh samples were analyzed prospectively. When fresh samples had not been analyzed, cryopreserved samples were thawed and tested with the same panel of mAbs. Samples obtained after relapse were not included in this analysis. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to sample collection as part of established research sample collection protocols.

A panel of directly conjugated mAbs was used to define functionally distinct T-cell subsets, as previously described.14 Three major T-cell populations: CD4+ T-regulatory cells (CD4Treg), conventional CD4 cells (CD4Tcon), and effector CD8+ T cells, were defined as CD3+CD4+Foxp3+, CD3+CD4+Foxp3−, and CD3+CD4−CD8+, respectively. Within each population, subsets were defined as follows: naive T cells (CD45RA+CD62L+); central memory (CD45RA−CD62L+); effector memory (CD45RA−CD62L−); and CD8 terminal effector memory T cells (CD8+CD45RA+CD62L−). In addition, we quantified the populations of PD-1+ cells among all subsets.

Statistical considerations

Patient baseline characteristics and immunophenotype data were analyzed descriptively. Endpoints of interest included overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), relapse, nonrelapse mortality (NRM), as well as acute and chronic GVHD. OS was defined as the time from stem cell infusion to death from any cause. Patients who were alive or lost to follow-up were censored at the time last seen alive. PFS was defined as the time from stem cell infusion to disease relapse, progression, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients who were alive without disease relapse or progression were censored at the time last seen alive and progression-free. OS and PFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for comparisons of Kaplan-Meier curves. Cumulative incidence curves for nonrelapse death, relapse with or without death, and GVHD were constructed in the competing risks framework considering relapse, NRM, and death or relapse without developing GVHD, respectively, as competing events. All time to events were measured from the date of stem cell infusion. The difference between cumulative incidence curves in the presence of a competing risk was tested using the Gray method.15 Immunophenotype data were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test for unpaired group comparison and Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired comparison. Correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman rank test. All tests are 2-sided at the significance level of 0.05 and multiple comparisons were not considered. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 3.1.3 (the CRAN project).

Results

Patients

A total of 39 patients who were treated with PD-1 blockade prior to HSCT (4 in combination with the anti-CTLA-4 mAb IPI) were included in this analysis. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Median age at the time of transplantation was 34 years (range, 21-67). Thirty-one patients (79%) were transplanted for classical HL, and the remainder for NHL. Patients received a median of 4 systemic treatments (range 2-8). Eighty-two percent received an autologous HSCT a median of 23 months (range 2-132) prior to allogeneic HSCT. Among the 31 patients with HL, 24 (77%) were treated with brentuximab, in 22 cases prior to PD-1 therapy. Patients received a median of 8 (range, 3-27) cycles of a PD-1 inhibitor. The best response to PD-1 therapy was a complete response (CR) in 14 patients (36%), partial response in 10 patients (26%), stable disease in 7 patients (18%), and progressive disease in 8 patients (21%). The overall response rate was higher among patients with HL (74%) compared with NHL (13%). The median time from last dose of PD-1 therapy to HSCT was 62 days (range, 7-260). Nineteen patients (49%) had intervening salvage therapy between anti-PD-1 treatment and HSCT, all for progression after PD-1 blockade. All patients received T-cell–replete grafts, and all but 1 patient had RIC.

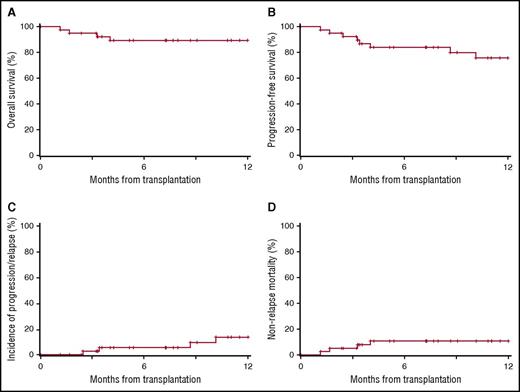

Survival and relapse

Median follow-up for survivors was 12 months (range, 2-33 months). Overall, the 1-year OS and PFS were 89% (95% confidence interval [CI], 74-96) and 76% (95% CI, 56-87), respectively, whereas the 1-year cumulative incidences of relapse (CIR) and NRM were 14% (95% CI, 4-29) and 11% (95% CI, 3-23), respectively (Figure 1; Table 2). Among the 31 patients with HL, 1-year OS, PFS, CIR, and NRM were 90% (95% CI, 71-97), 74% (95% CI, 50-88), 16% (95% CI, 3-36), and 10% (95% CI, 3-25), respectively (Table 2).

OS, PFS, CIR, and NRM following HSCT in patients previously treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. (A) OS, (B) PFS, (C) CIR, and (D) NRM.

OS, PFS, CIR, and NRM following HSCT in patients previously treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. (A) OS, (B) PFS, (C) CIR, and (D) NRM.

Toxicity

The 1-year cumulative incidences of grade 2-4, grade 3-4, and grade 4 acute GVHD were 44%, 23%, and 13%, respectively, with a median day of onset of 27 days. The 1-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD was 41%. The rates of GHVD were similar for the HL cohort (Table 2). There were 4 treatment-related deaths: 3 from acute GVHD arising within 14 days of HSCT and 1 from hepatic SOS (Table 2). Among the 3 patients with fatal acute GHVD, 2 patients (patients 3 and 8) had a noninfectious febrile syndrome, which began within 1 week of transplant and 4 to 6 days prior to neutrophil engraftment. Patient 3 developed severe acute GVHD, bacteremia, acute kidney injury, and hypoxic respiratory failure leading to death on day 100. Following an initial noninfectious febrile syndrome, patient 8 also developed severe acute GHVD, which was complicated by bacteremia, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, and death on day 123. The third patient with fatal GVHD (patient 18) had a pretransplant course complicated by grade 2 colitis and pneumonitis after prior combination treatment with nivolumab and IPI. After transplantation, she developed severe liver GVHD, hepatic encephalopathy, and hypotension. A liver biopsy prior to her death on day 35 demonstrated acute liver GVHD as well as lobular hepatitis consistent with drug-induced hepatitis (Figure 2). Her last treatment with nivolumab and IPI was 49 days before HSCT and 74 days prior to the biopsy.

Liver biopsy from patient with acute liver failure after HSCT compared with example cases. (A) Example case, low power image of GVHD (left) with minimal lobular inflammation in contrast to IPI-associated hepatitis (right) showing pronounced lobular hepatitis (original magnification ×50; hematoxylin and eosin stain). (B) Example case, high power view of a portal tract in a patient with GVHD exhibiting cholestasis and bile duct injury, evidenced by cells with nuclear pleomorphism, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles (original magnification ×400; hematoxylin and eosin stain). (C) Example case, high power image of IPI-associated hepatitis exhibiting a pan-lobular, predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate with spotty hepatocellular necrosis (original magnification ×200; hematoxylin and eosin stain). (D-F) Patient case demonstrating striking centrizonal hemorrhage and hepatocellular dropout as well as bile duct injury. (D) Original magnification ×50; hematoxylin and eosin stain. (E) Original magnification ×400; hematoxylin and eosin stain. (F) Original magnification ×400; hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Liver biopsy from patient with acute liver failure after HSCT compared with example cases. (A) Example case, low power image of GVHD (left) with minimal lobular inflammation in contrast to IPI-associated hepatitis (right) showing pronounced lobular hepatitis (original magnification ×50; hematoxylin and eosin stain). (B) Example case, high power view of a portal tract in a patient with GVHD exhibiting cholestasis and bile duct injury, evidenced by cells with nuclear pleomorphism, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles (original magnification ×400; hematoxylin and eosin stain). (C) Example case, high power image of IPI-associated hepatitis exhibiting a pan-lobular, predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate with spotty hepatocellular necrosis (original magnification ×200; hematoxylin and eosin stain). (D-F) Patient case demonstrating striking centrizonal hemorrhage and hepatocellular dropout as well as bile duct injury. (D) Original magnification ×50; hematoxylin and eosin stain. (E) Original magnification ×400; hematoxylin and eosin stain. (F) Original magnification ×400; hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Three patients (8%) developed severe hepatic SOS despite RIC. All 3 patients were treated with defibrotide, and 2 required central venovenous hemofiltration, with 1 fatality 51 days after transplant (patient 14; see Table 2). The third patient who developed severe SOS received corticosteroids in addition to defibrotide and recovered rapidly and completely.

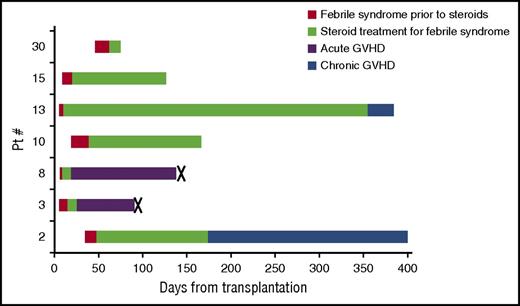

In addition, 7 patients (18%) developed a prolonged febrile syndrome beginning 1 to 7 weeks after HSCT with elevated transaminases in 3 patients and rash in 4 patients (Figure 3). Only 1 of 7 patients met Spitzer criteria and 3 of 7 patients met Maiolino criteria for engraftment syndrome.16,17 All patients were started on corticosteroids (∼1 mg/kg) within 3 weeks of fever onset. Two patients with this syndrome (patients 3 and 8) developed severe, fatal acute GVHD shortly after the onset of fevers, as described above. Of the remaining 5 patients, 4 required prolonged steroid courses for management of recurrent fevers, rash, or liver function test abnormalities (Figure 3). Two of those 4 patients developed clear chronic GVHD while on a steroid taper.

Febrile syndrome: time course among affected patients. Seven patients (18%) developed prolonged noninfectious febrile syndromes shortly after HSCT. They received allografts from 2 MMURD, 2 MURD, 2 haploidentical donors (haplo), and 1 MRD. Five grafts were PB and 2 were BM. (Patient 2: PB graft, MMUD; patient 3: PB graft, MMUD; patient 8: PB graft, MUD; patient 10: BM graft, haplo; patient 13: PB graft, MUD; patient 15: PB graft, MRD; patient 30: BM graft, haplo.) Patient 10 and 30 received PTCY. Red, febrile syndrome prior to steroids; green, treatment with steroids for febrile syndrome; purple, acute GVHD; blue, chronic GVHD; X, death. Both deaths were from complications of severe acute GVHD, described in detail in Table 2.

Febrile syndrome: time course among affected patients. Seven patients (18%) developed prolonged noninfectious febrile syndromes shortly after HSCT. They received allografts from 2 MMURD, 2 MURD, 2 haploidentical donors (haplo), and 1 MRD. Five grafts were PB and 2 were BM. (Patient 2: PB graft, MMUD; patient 3: PB graft, MMUD; patient 8: PB graft, MUD; patient 10: BM graft, haplo; patient 13: PB graft, MUD; patient 15: PB graft, MRD; patient 30: BM graft, haplo.) Patient 10 and 30 received PTCY. Red, febrile syndrome prior to steroids; green, treatment with steroids for febrile syndrome; purple, acute GVHD; blue, chronic GVHD; X, death. Both deaths were from complications of severe acute GVHD, described in detail in Table 2.

Clinical predictors of GVHD, survival, and NRM

PD-1 dosing and timing.

Patients who received greater than or equal to 8 doses (the median value in this cohort) of PD-1 blockade appeared to have improved PFS at 1 year compared with those receiving <8 doses (91% [95% CI 70-98] vs 54% [95% CI 25-76], P = .039). A slightly larger proportion of these patients had a CR at the time of HSCT, but the difference was not significant (69% vs 54%, P = .5). No significant differences were seen in 1-year rates of OS (95% [95% CI 72-99] vs 77% [95% CI 44-92], P = .064), CIR (4% vs 23%, P = .4), and NRM (5% vs 23%, P = .070) when stratified by total doses of PD-1 (8 or more doses vs <8 doses). Duration of time between the last dose of PD-1 blockade and HSCT (>60 days vs <60 days) did not significantly affect 1-year rates of OS, PFS, CIR, NRM, or the incidence of GVHD or febrile syndrome.

The 4 patients treated concurrently with IPI and a PD-1 inhibitor all developed acute GVHD, including 1 fatal case of grade 4 acute GVHD. The 6-month rate of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was higher in these patients compared with those treated with PD-1 blockade alone (75% vs 17% P = .010). There were no significant differences seen in 1-year OS (75% vs 91% P = .3), 10-month PFS (75% vs 80% P = .13), 10-month CIR (0% vs 11% P = .4), 10-month NRM (25% vs 9% P = .3), or 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD (25% vs 43%, P = .8).

Donor and graft characteristics.

Among patients receiving BM grafts, rates of grade 3-4 acute GVHD were lower compared with patients receiving peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs; 0% vs 32%, P = .036), but this did not result in a significant difference in chronic GVHD, NRM, or survival. There were no significant differences in outcomes based on donor source (ie, matched vs unmatched). Among the 14 patients undergoing haploidentical donor transplants, 1-year OS, PFS, CIR, and NRM were similar to the entire cohort (OS 93% [95% CI, 59-99], PFS 70% [95% CI, 30-90], CIR 23% [95% CI, 2-56], and NRM 7% [95% CI, 0-28]). Likewise, there were no significant differences based on GVHD prophylaxis regimen, treatment with a salvage regimen between PD-1 blockade and HSCT, or timing of prior autologous HSCT.

Immune reconstitution after HSCT

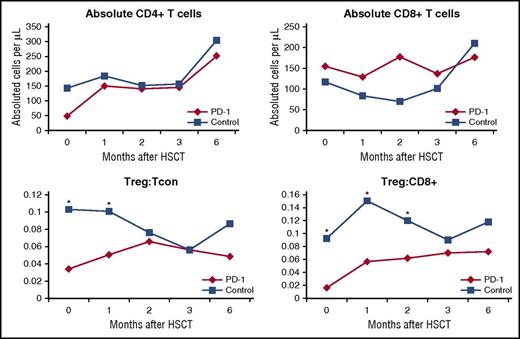

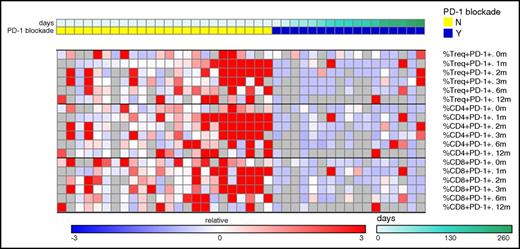

Seventeen of 19 patients who underwent HSCT at DFCI/BWH had blood samples available and were included in a subgroup analysis. Twenty-four patients treated with RIC HSCT during the same time period were assembled as a control cohort. They were matched as able for disease, conditioning intensity, sex, and GVHD prophylaxis regimen (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). Patients treated with PD-1 blockade prior to HSCT had similar absolute counts of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells across studied time points (0, 1, 2, 3, and 6 months) after transplantation (Figure 4). Likewise, there were no significant differences in subset populations of naive T cells, central memory, effector memory, or CD8 terminal effector memory T cells between the PD-1 and control cohort. However, among patients previously treated with PD-1 blockade, the ratio of CD4Treg:CD4Tcon cells was significantly decreased at 0 and 1 months and the ratio of CD4Treg:CD8 T cells was significantly reduced at 0, 1, and 2 months after transplantation (Figure 4). Further examination of CD4Treg, CD4Tcon, and CD8 T-cell subsets revealed that the expression of PD-1 was significantly decreased across all examined T-cell subsets at the time of transplant (0 months) and 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after HSCT (Figure 5), despite a median time from last PD-1 treatment to transplant of 148 days in this subgroup (range, 7-260).

Immune reconstitution analysis of T-cell subsets. T-cell subsets were quantified from blood samples from the PD-1 and control cohorts on day 0 (baseline) as well as 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after HSCT. Tcon, conventional CD4 cells (*P < .05); Treg, T-regulatory cell.

Immune reconstitution analysis of T-cell subsets. T-cell subsets were quantified from blood samples from the PD-1 and control cohorts on day 0 (baseline) as well as 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after HSCT. Tcon, conventional CD4 cells (*P < .05); Treg, T-regulatory cell.

PD-1 expression among case and control patients displayed as heatmap. PD-1 expressing cells were quantified at the time of HSCT (0 months) and at multiple post-HSCT time points (1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after HSCT) in a control cohort (left columns, yellow top bar) and in patients previously treated with PD-1 (right columns, blue top bar). Each column represents an individual patient. The PD-1 cohort is arranged by time from last PD-1 treatment to HSCT (see legend). The percentage of PD-1+ cells among various T-cell subsets is displayed as a heatmap where blue, white, and red represent low-, intermediate-, and high-subset frequency, respectively. Gray indicates missing value. Values in each row were subtracted from row median and divided by row median absolute deviation. Treg, T-regulatory cells; Tcon, conventional CD4 cells. PD-1 expression was significant lower on Treg cells, Tcon cells, and CD8+ cells at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 6 months. N, no; Y, yes.

PD-1 expression among case and control patients displayed as heatmap. PD-1 expressing cells were quantified at the time of HSCT (0 months) and at multiple post-HSCT time points (1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after HSCT) in a control cohort (left columns, yellow top bar) and in patients previously treated with PD-1 (right columns, blue top bar). Each column represents an individual patient. The PD-1 cohort is arranged by time from last PD-1 treatment to HSCT (see legend). The percentage of PD-1+ cells among various T-cell subsets is displayed as a heatmap where blue, white, and red represent low-, intermediate-, and high-subset frequency, respectively. Gray indicates missing value. Values in each row were subtracted from row median and divided by row median absolute deviation. Treg, T-regulatory cells; Tcon, conventional CD4 cells. PD-1 expression was significant lower on Treg cells, Tcon cells, and CD8+ cells at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 6 months. N, no; Y, yes.

Total leukocyte donor chimerism values were slightly but significantly lower in the control group compared with the PD-1 cohort at 30 days after HSCT (median donor chimerism 95% [range 34% to 100%] vs 99% [range 0% to 100%], p = .036). A similar trend was seen for day 30 CD3 chimerism (75% [range 6% to 100%] vs 87% [range 1% to 100%], p=.40). At 100 days, both total leukocyte and CD3 donor chimerism values were significantly lower in the control cohort compared with PD-1 cohort (total leukocyte 95% [range 15% to 100%] vs 100% [range 60% to 100%], p = .027; CD3 64% [range 25% to 100%] vs 97% [range 56% to 100%], p = .015).

Discussion

Preclinical studies have suggested that immune activation from checkpoint blockade could lead to both increased immune-related toxicity and antitumor activity.9-11 Our results strongly support the hypothesis that prior checkpoint blockade affects HSCT outcomes, based on several aspects of this cohort. In terms of toxicity, we observed a higher than expected rate of early severe transplant-related complications. Although the overall incidences of acute and chronic GVHD did not appear very different from that expected in a population of patients undergoing T-cell replete RIC HSCT for lymphoma, the incidence of grade 4 acute GVHD appears higher than prior studies (13% vs 3% to 4%)18,19 ; in addition, the 3 patients who succumbed to GVHD developed a particularly rapid and virulent form of acute GVHD, which is rare after RIC HSCT. These early deaths prompted a US Food and Drug Administration label warning for use of HSCT after prior PD-1 blockade. In further support of the possible role of prior checkpoint blockade, the liver biopsy of one of the patients with fatal GVHD (Figure 2) provides histologic evidence of both GVHD and drug-induced hepatitis, strongly suggesting that prior checkpoint blockade may have magnified the severity of liver injury. In addition, severe SOS is a rare event in the RIC setting, and the rate of severe SOS in this cohort appeared greater than that seen in a prior large retrospective series of RIC allogeneic transplants (8% vs 2.1%).20 We also report an atypical noninfectious febrile syndrome that occurred in a sizeable minority of patients. The majority of these patients did not meet criteria for engraftment syndrome and required much longer courses of steroid treatment than is typically seen in engraftment syndrome. The syndrome also appeared to be distinct from reports of cytokine-release syndrome in patients receiving PTCY after a haploidentical PBSC. None of the 7 patients we report received PTCY after a haploidentical PBSC, and the onset of fevers is delayed in our cohort (median, 15 days; range, 6-47 days) compared with those reported with cytokine-release syndrome, which occurred within 72 hours of HSCT.21 As many of these patients went on to develop GVHD, this febrile syndrome may lie on the same immunologic/inflammatory spectrum as GVHD. Prospective assessment with measurements of cytokines and immune activation is needed to better define this phenomenon.

Despite these toxicities, the rate of NRM was not appreciably higher than previously published series in similar patient populations.22-25 Furthermore, HSCT after PD-1 blockade may be associated with lower than expected relapse rates. CIR at 1 year in this study compares favorably to that expected for this cohort based on the Disease Risk Index mix of patients (14% vs 26%).26 Among the HL subgroup, the 1-year relapse rate appears lower than that observed in many historical series of HL patients undergoing RIC allogeneic transplant (16% vs 26% to 41%)18,19,22,24,27 ; however, patients in most of these series likely had a higher disease burden at the time of HSCT compared with our cohort. Rates of relapse were similar to that seen in 1 small phase 2 trial of RIC for HL in which patients had a comparable rate of CR prior to transplant.28 Clearly longer-term follow-up of larger populations is necessary (which is ongoing, as we continue to expand this collaboration and follow the patients included). Nonetheless, our results at least lend credence to a possible accentuation of GVT by prior PD-1 blockade.

Immune profiling of circulating T-cell subsets also supports an immunologic difference in patients treated with PD-1 blockade. Although it was not possible to create a control cohort for this analysis that was perfectly matched with respect to all possible salient characteristics (eg, age, disease, sex, donor, graft source, GVHD prophylaxis), we observed clear patterns of differences in immune reconstitution after PD-1 exposure that warrant additional investigation. Specifically, the increased rates of early immune complications and potentially decreased relapse rates may be due to imbalanced T-cell recovery after transplantation. Prior checkpoint blockade therapy did not appear to affect the overall recovery of CD4 or CD8 T cells after transplant, but patients treated with anti-PD-1 mAbs had a decreased Treg:CD4Tcon ratio at 0 and 1 months after transplant and a decreased Treg:CD8 ratio at 0, 1, and 2 months after HSCT when compared with matched controls (Figure 4). In prior studies, a ratio of Treg:CD4Tcon cells of <9% predicted both increased incidence and severity of acute GVHD, and the ratio was 3% to 5% in our PD-1 cohort vs 10% to 11% in controls.29,30 In addition, decreased Treg:CD4Tcon ratios may also predict an augmented GVT effect as observed in a trial of IPI for relapse after HSCT where there was a trend among clinical responders of lower Treg:CD4Tcon.13

Notably, the immune profiling results also demonstrate severe and persistent depletion of PD1+ T cells in patients exposed to prior PD-1 blockade, a finding that to our knowledge has not been published previously. Decreased PD-1 expression could contribute to the relative decrease in Treg cell populations, as the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway appears to be important in the conversion of type 1 T helper cells to Treg cells and maintenance of Treg populations.31,32 Of particular practical relevance, the depletion of PD-1+ T cells was strongly apparent despite a median interval from PD-1 blockade to HSCT of over 4 months and persisted for at least 6 months after HSCT. Chimerism data confirm that prior PD-1 inhibition does not negatively affect engraftment; moreover, the high T-cell chimerism among PD-1–pretreated patients confirms that the differences we observed in PD-1 expression and T-cell subsets must indeed involve donor T cells. For patients with a short interval between PD-1 therapy and HSCT, residual circulating antibodies may explain decreased PD-1 detection early after transplant; however, the mechanism of prolonged decreased PD-1 expression after HSCT is not clear. The PD-1 pathway is critical for both positive and negative selection of T cells in the thymus and is necessary for development of systemic self-tolerance.33-36 As such, previous PD-1 blockade could have long-lasting effects on the thymus, resulting in altered PD-1 expression and imbalanced processing of the large number of T cells infused during HSCT. In addition, PD-1 blockade may alter posttransplant immune reconstitution through its effects on circulating cytokines and antigen-presenting cells.10,11 Alternatively, the pattern of prolonged PD-1 depletion in combination with evidence of immunelike liver toxicity (Figure 2) in a patient who had last received checkpoint blockade >10 weeks earlier might suggest that PD-1 inhibitors have longer effective half-lives than measured by pharmacokinetic analyses in blood (roughly 4 weeks).5,37 Regardless of the mechanism of PD-1 depletion, our results imply that anti-PD-1 therapy creates a long-lasting disturbance in the composition of circulating T-cell populations. These findings would explain the absence of any apparent association between the time interval from PD-1 to transplantation and early toxicity and suggests that the use of a window period to delay HSCT for even several months after PD-1 therapy may not mitigate the impact of this therapy on HSCT outcomes.

Although the associations we examined are only hypothesis generating in nature and in no way intended to support definitive conclusions, they suggest that patients receiving PD-1 blockade who are considering allogeneic HSCT could possibly benefit from receiving at least 8 doses of a PD-1 inhibitor, when clinically possible; this hypothesis should be validated in future studies. In addition, we observed a dramatic decrease in the rate of severe acute GVHD among patients receiving BM compared with PBSC grafts. This pattern has been reported previously, but to a lesser degree than our preliminary findings.38 Although rates of NRM and PFS were not significantly reduced among recipients of BM grafts, this approach may be beneficial for GVHD control. We also noted significantly higher rates of acute GVHD in patients who received combined therapy with IPI and PD-1 blockade prior to HSCT, suggesting that HSCT in such patients likely carries increased risk and should be performed cautiously. Additional studies of a larger patient cohort are clearly needed to validate and refine these findings.

We acknowledge that this analysis has several limitations. In order to report all known cases of allogeneic HSCT after prior PD-1 therapy, we included patients regardless of their transplant regimens. The heterogeneity of transplant strategies makes interpretation of subset analyses more challenging. Although we directly contacted all centers involved in the early phase studies of PD-1 inhibitors for lymphoma, the growing use of PD-1 blockade on- and off-label makes it impossible to include all patients worldwide who received HSCT after PD-1 blockade. We therefore acknowledge the possibility of selection bias in reporting patient outcomes, although our recruitment strategy, which was center based rather than patient based, should effectively minimize this bias. Finally, the control cohort for the immune reconstitution analysis was older and could not be perfectly matched for all important transplant-related variables, as discussed above.

There are currently many questions regarding the role and appropriateness of HSCT after PD-1 blockade. The sample size and follow-up of this study are limited, which precludes examination of long-term outcomes and limits our ability to study predictive markers of efficacy or toxicity. Despite these limitations, with a 1-year PFS of over 75% in a population of heavily pretreated patients with advanced disease, our study does demonstrate that HSCT after PD-1 blockade is feasible in appropriately selected patients and may be associated with increased immune toxicity but also good disease control. We conclude that prior PD-1 blockade should not be considered a contraindication to HSCT in this patient population.

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Orlando, FL, 6 December 2015.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to the patients whose course is herein reported, and who staked their lives on decisions made under heavy uncertainty—some with excellent, and some with devastating outcomes, but all with great courage and generosity.

This study was supported in part by research funding from the Harold and Virginia Lash/David Lash Fund for Lymphoma Research (P.A.), by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (grant 15835) (C.C.-S.), by the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Fund: Leukemia Research Fund in Leukemia and Transplantation (R.J.S.), and by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants (R01CA183559 and R01CA183560) (R.J.S. and J.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: R.W.M. designed the research, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; H.T.K. designed the research, collected and analyzed data, and edited the manuscript; P.L.Z., C.C.-S., S.M.A., M.-A.P., A.A., A.S.H., R.H., T.M., N.D., W.L., A.T.-B., S.F., A.S.-B., P.-S.R., H.L.W., L.C., A. Santoro, J.R., S.C.B., A. Srivastava, H.K., E.P., M.C., C.R., V.T.H., and J.H.A. collected data and edited the manuscript; V.B. edited the manuscript; R.J.S. designed the research, collected data, and edited the manuscript; and P.A. designed the research, collected and analyzed data, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.L.Z. received consulting fees from Roche, Celegene, MSK, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and AbbVie Inc. C.C.-S. received consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, research support from Rhizen Pharmaceuticals, and travel reimbursement from Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. S.M.A. received institutional research funding from BMS, Merck, Seattle Genetics, and Affimed Pharmaceuticals. M.-A.P. received consulting fees from Merck, Incyte, and Seattle Genetics. R.H. received an honorarium and consulting fees from BMS. P.-S.R. received an honorarium from Sanofi Aventis, consulting fees from Amgen, and travel reimbursement from Pierre Fabre. A. Santoro received consulting fees from Amgen, Takeda, Novartis, and ArQule. V.B. received research funding from Alopexx, Oxis Inc, and Novartis. J.H.A. received royalties from Wiley-Thomas Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. R.J.S. received an honorarium from Gilead, consulting fees from Juno and Jazz Pharmaceutical, and travel reimbursement from Gilead, Kiadis, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. He served on a supervisory board at Kiadis. P.A. received consulting fees from BMS, Merck, and Infinity Pharmaceuticals, and institutional research support from BMS, Merck, Affimed, Pfizer, Roche, Tensha Therapeutics, Sequenta, Otsuka, and Sigma Tau. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Philippe Armand, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston MA 02215; e-mail: parmand@partners.org.