Key Points

Treatment with single-agent ibrutinib can increase susceptibility to PCP in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients.

Key components of PCP diagnosis are increased clinical suspicion and adequate sampling with diagnostic bronchoscopy.

Abstract

Ibrutinib is not known to confer risk for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP). We observed 5 cases of PCP in 96 patients receiving single-agent ibrutinib, including 4 previously untreated. Clinical presentations included asymptomatic pulmonary infiltrates, chronic cough, and shortness of breath. The diagnosis was often delayed. Median time from starting ibrutinib to occurrence of PCP was 6 months (range, 2-24). The estimated incidence of PCP was 2.05 cases per 100 patient-years (95% confidence interval, 0.67-4.79). At the time of PCP, all patients had CD4 T-cell count >500/μL (median, 966/μL) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) >500 mg/dL (median, 727 mg/dL). All patients underwent bronchoalveolar lavage. P jirovecii was identified by polymerase chain reaction in all 5 cases; direct fluorescence antibody staining was positive in 1. All events were grade ≤2 and resolved with oral therapy. Secondary prophylaxis was not given to 3 patients; after 61 patient-months of follow up, no recurrence occurred. Lack of correlation with CD4 count and IgG level suggests that susceptibility to PCP may be linked to Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibition. If confirmed, this association could result in significant changes in surveillance and/or prophylaxis, possibly extending to other BTK inhibitors. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01500733 and #NCT02514083.

Introduction

The Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib is approved for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, and mantle cell lymphoma. Ibrutinib is associated with lower rates of infection1,2 compared with combination chemoimmunotherapy in CLL.3,4 Pneumonia is the most common presentation of infection associated with ibrutinib found in 4% to 17% of patients,1,2,5 and, thus far, has not been linked to specific opportunistic pathogens. The risk of infection appears to be highest in the first 6 months and decreases thereafter, consistent with indications of improving immune function on ibrutinib.6 Although Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) has been rarely reported in previously untreated CLL,7,8 treatment with a fludarabine-based regimen has long been thought to increase the risk of PCP9 and prophylaxis is recommended for patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy.3,4,10 Here we report, for the first time, 5 cases of PCP in 96 CLL patients treated with single-agent ibrutinib under 2 prospective studies.

Study design

Two investigator-initiated studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (#NCT01500733 and #NCT02514083). All patients provided written informed consent. Patients with respiratory symptoms or abnormal chest computed tomography (CT) findings underwent comprehensive workup, including bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). BAL samples were cultured for bacteria and fungi, tested for viruses by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and for P jirovecii by PCR, direct fluorescent antibody (DFA), and Gomori-methenamine silver stains. Patients were diagnosed with PCP based on positive P jirovecii PCR in BAL, accompanied by respiratory signs and symptoms or CT abnormalities that could not be explained by other pathogens, and resolved with anti-Pneumocystis treatment.

Results and discussion

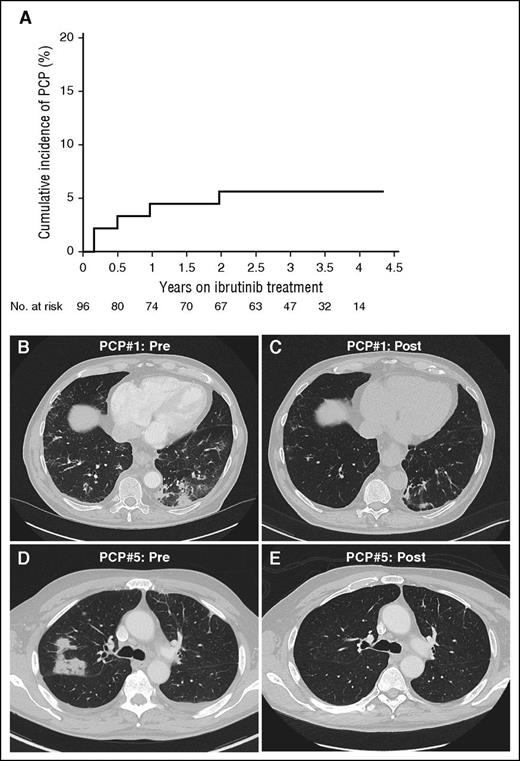

The estimated incidence of PCP was 2.05 cases per 100 patient-years (95% confidence interval, 0.67-4.79). The estimated cumulative incidence of PCP was 4.5% at 1 year, and 5.6% at 2 years (Figure 1A).11 Four patients were previously untreated and none were on long-term steroids or other immunosuppressive agents. Baseline characteristics and clinical presentations are summarized in Table 1. Median time from the start of ibrutinib to the onset of PCP was 6 months (2-24 months). Clinical presentations varied between asymptomatic and mild dyspnea and cough, sometimes chronic. CT showed multifocal nodular infiltrates. In 2 cases, the lack of suspicion for PCP resulted in months of diagnostic workup and ineffective treatments. Pneumocystis was identified by PCR in BAL in all 5 cases and by DFA in 1 case. Other microorganisms were concurrently isolated in 3 patients (Table 1) but were not considered to be likely pathogens. All patients had a CD4+ T-cell count >500/μL (median, 966/μL) and IgG >500 mg/dL (median, 727 mg/dL) at the time of or less than 2 months prior to PCP diagnosis. All patients responded clinically and radiologically to oral therapy, with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) in 4 patients, and TMP/SMX followed by atovaquone in 1 patient. No patient required IV antibiotics, steroids, or ventilatory support. Two patients received secondary prophylaxis due to the anticipated addition of chemoimmunotherapy as planned by the trial. Two case descriptions follow.

Estimated cumulative incidence rate and radiologic presentation of P jirovecii in a CLL patient treated with ibrutinib. (A) The estimated cumulative incidence of PCP in CLL is 4.5% at 1 year on ibrutinib, and 5.6% at 2 years and thereafter. The cumulative incidence of PCP was estimated by considering deaths or early discontinuation of ibrutinib without PCP as competing risk events; otherwise, patients on ibrutinib treatment were censored at the last follow up if no PCP was observed.11 (B-E) Chest CT images of 2 patients are shown who were diagnosed with and treated for PCP while on ibrutinib. The first patient presented with multifocal ground-glass opacificies (B), which significantly improved after treatment of PCP (C). The second patient presented with unilateral nodular infiltrates (D), which resolved after treatment (E).

Estimated cumulative incidence rate and radiologic presentation of P jirovecii in a CLL patient treated with ibrutinib. (A) The estimated cumulative incidence of PCP in CLL is 4.5% at 1 year on ibrutinib, and 5.6% at 2 years and thereafter. The cumulative incidence of PCP was estimated by considering deaths or early discontinuation of ibrutinib without PCP as competing risk events; otherwise, patients on ibrutinib treatment were censored at the last follow up if no PCP was observed.11 (B-E) Chest CT images of 2 patients are shown who were diagnosed with and treated for PCP while on ibrutinib. The first patient presented with multifocal ground-glass opacificies (B), which significantly improved after treatment of PCP (C). The second patient presented with unilateral nodular infiltrates (D), which resolved after treatment (E).

Case #1

A 69-year-old male with CLL presented after 2 cycles of ibrutinib. Restaging CT scan prior to cycle 3 showed a reduction of lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, but revealed a new ground-glass opacity in the left lower lung lobe (Figure 1B). He denied respiratory symptoms or fever. BAL was negative except for positive PCR for P jirovecii. DFA and Gomori-methenamine silver stains were negative. Treatment with TMP/SMX was administered for 21 days followed by prophylaxis. Follow-up chest CT a month after PCP diagnosis showed near complete resolution of the infiltrate (Figure 1C).

Case #2

A 65-year-old male with CLL and hypogammaglobulinemia supported with IVIG replacement for years began ibrutinib. At 23 months on ibrutinib, he reported a dry cough that had persisted for 7 months despite empiric treatments with moxifloxacin and oral steroids. Chest CT showed thickened bronchioles and small bilateral ground-glass patches. Sputum grew Klebsiella pneumoniae, which was initially treated with oral levofloxacin and subsequently with the addition of inhaled tobramycin without improvement of symptoms. BAL revealed positive P jirovecii by PCR. No other pathogen was identified. He was started on TMP/SMX but a new rash prompted switching to atovaquone. The cough improved after 1 week of therapy, and then resolved completely. He was not given PCP prophylaxis and has remained well.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of PCP in patients treated with single-agent ibrutinib. PCP appears to be related to ibrutinib as all 5 patients were diagnosed with PCP during ibrutinib-only periods. Two patients, treated under the study using ibrutinib and short-course fludarabine, developed PCP during ibrutinib-only cycles, and none was exposed to fludarabine prior to PCP. The remaining 3 patients were treated under a different study using single-agent ibrutinib. Four of 5 cases occurred in previously untreated patients receiving ibrutinib in first-line and presented as mild disease, varying from asymptomatic multifocal pulmonary infiltrates to chronic cough. Atypical presentations of PCP have been described,7,12 but it is unclear if mild disease reflects the natural history of PCP in this patient population or increased vigilance and early identification.

PCP is best known as the cause of severe interstitial pneumonia in AIDS patients. However, due to improved treatment of HIV, some institutions now find most PCP cases in HIV-negative immunocompromised individuals.12 HIV-negative patients present with a lower burden of pathogen, which limits the diagnostic sensitivity of staining methods.12 Although some controversy remains regarding the significance of a positive PCR with a negative stain,13,14 in our cases, the presence of a compatible clinical picture, lack of other likely pathogens, and response to anti-Pneumocystis treatment allow us to make the diagnosis of PCP by PCR only. Of note, the 1 case with positive DFA (case #4) was quite similar to the others.

The mechanism by which ibrutinib may increase susceptibility to Pneumocystis requires additional study. Although T cells are considered the most important immune component to control Pneumocystis (with <200 CD4+ T cells/μL commonly used to define risk),15 data support a role for both B cells and macrophages. Of interest, PCP has been described in X-linked agammaglobulinemia (a BTK deficiency) as the initial manifestation of the immunodeficiency.16 Almost all these cases happened as the presenting infection, suggesting that hypogammaglobulinemia plays a role and that IVIG replacement may be beneficial. Additionally, there is also an increased frequency of PCP in patients treated with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies regardless of Ig levels, supporting the importance of additional functions of B cells such as antigen presentation.17 Other B-cell immunodeficiencies, such as CD40 and CD40 ligand deficiency, are also known to have an increased risk of PCP.18 Finally, the effects of BTK inhibition on monocyte function may also contribute, given that alveolar macrophages are necessary to clear the organism.19

Establishing the risk of PCP in patients treated with ibrutinib will be important to decide whether prophylaxis or increased surveillance is the appropriate strategy. It is noteworthy that 3 patients in our series did not receive immediate secondary prophylaxis and all have remained free of recurrence; one of the patients electively began TMP/SMX after a year of observation. Currently, we do not advocate universal Pneumocystis prophylaxis for patients receiving ibrutinib in the absence of other risk factors, but we believe that increased awareness and active vigilance are appropriate.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for participating and donating samples to make this research possible, and acknowledge Pharmacyclics Inc for providing study drug and comments on a draft of this manuscript.

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute.

Authorship

Contribution: X.T. performed statistical analyses; and all authors participated in the research concept and design, acquisition and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.W. received research funding from Pharmacyclics Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Juan Gea-Banacloche, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Dr, Room 13E/3-3330, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: banacloj@mail.nih.gov; and Adrian Wiestner, Hematology Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Dr, Building 10, CRC 3-5140, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: wiestnea@nhlbi.nih.gov.

References

Author notes

I.E.A. and T.J. are joint first authors.