In this issue of Blood, Yildiz et al report that recurrent STAT6 mutations in follicular lymphoma (FL) are activating and provide evidence that supports a genetic basis for activation of the IL-4/JAK/STAT6 axis as a driver of FL pathogenesis.1

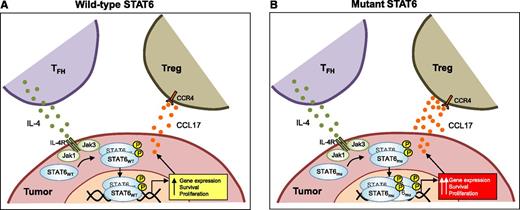

In follicular lymphoma tumors, IL-4 produced by TFH binds to its receptor (IL-4R) on tumor cells and leads to activation of Jak1 and Jak3, which, in turn, results in phosphorylation, dimerization, and translocation of STAT6 to the nucleus. Phosphorylated STAT6 induces genes that may promote survival and proliferation of the tumor cells and also stimulates production of CCL17, which facilitates recruitment of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) via CCR4. Compared with wild-type (wt) STAT6 (STAT6WT) (A), mutant STAT6 (STAT6mu) (B) results in increased localization of STAT6 to the nucleus, especially in the presence of IL-4, and leads to increased expression of genes, including those that might promote survival and proliferation and facilitate immune evasion.

In follicular lymphoma tumors, IL-4 produced by TFH binds to its receptor (IL-4R) on tumor cells and leads to activation of Jak1 and Jak3, which, in turn, results in phosphorylation, dimerization, and translocation of STAT6 to the nucleus. Phosphorylated STAT6 induces genes that may promote survival and proliferation of the tumor cells and also stimulates production of CCL17, which facilitates recruitment of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) via CCR4. Compared with wild-type (wt) STAT6 (STAT6WT) (A), mutant STAT6 (STAT6mu) (B) results in increased localization of STAT6 to the nucleus, especially in the presence of IL-4, and leads to increased expression of genes, including those that might promote survival and proliferation and facilitate immune evasion.

The role of the microenvironment in supporting the survival and growth of FL has been suggested by many studies. For example, FL tumor cells undergo spontaneous apoptosis when cultured in vitro but may be rescued by various cytokines and stromal cells.2 More interestingly, in gene expression profiling studies, the clinical outcome of FL patients was associated with gene signatures of stromal cells rather than the tumor cells,3 suggesting a role for the microenvironment in vivo. However, recent studies indicated that multiple recurrently mutated genes might be involved in the pathogenesis of FL.4-6 Whether such recurrent mutations act independently or in concert with the signals from the microenvironment to promote FL pathogenesis has been unclear. The report by Yildiz et al suggests that recurrent STAT6 mutations might act in concert with interleukin-4 (IL-4), a cytokine shown to be present at elevated levels in the microenvironment of FL (see figure).7 IL-4 is produced by follicular helper T cells (TFH), and IL-4–producing TFH are increased in FL compared with normal lymphoid tissues.8,9 Binding of IL-4 to its receptor activates Jak1 and Jak3, leading to phosphorylation of STAT6 and its translocation to the nucleus, where it activates STAT6-responsive genes. In in vitro studies, recombinant human IL-4 with or without CD40 ligand (CD40L), another molecule expressed at high levels by TFH, promoted the survival and proliferation of FL tumor cells.2 In addition, IL-4 and/or CD40L induced production of chemokines CCL17 and CCL22, which induce preferential chemotaxis of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells via CCR4, which, in turn, might promote immune evasion by the tumor.9 Collectively, these results suggested a role for TFH via the IL-4/JAK/STAT6 pathway and possibly the CD40-CD40L pathway in the pathogenesis of FL.

In their study, Yildiz et al demonstrated that recurrent STAT6 mutations might be yet another mechanism that activates the IL-4/JAK/STAT6 pathway in FL.1 They show that these mutations might act independently but are likely to be more consequential in the presence of IL-4. In their series of 114 FL tumors, recurrent STAT6 mutations were found in 11% of FL tumors. Further analysis showed that amino acid 419 of STAT6 is a mutation hotspot in FL. In a series of elegant functional experiments using transfected cell lines, luciferase reporter assays, and gene expression profiling studies, they showed that the STAT6 mutations were activating. Immunofluorescence studies revealed that STAT6 mutants preferentially localized to the nucleus compared with wt STAT6, and structural modeling showed that most of the mutations occurred at the DNA binding domains of STAT6. Although STAT6 mutants constitutively induced varying levels of STAT6 responsive genes, their effects were most noticeable in the presence of IL-4, suggesting that they augmented the response to IL-4. More importantly, STAT6 target genes were expressed at elevated levels in primary FL tumors with mutant compared with wt STAT6, suggesting that these mutations might induce altered gene expression profiling in the tumors in vivo. However, whether these mutations affect the survival, apoptosis, and proliferation of FL tumor cells and whether they have prognostic significance have not been examined. Intriguingly, all FL STAT6 mutant tumors were associated with inactivating mutations in CREBBP, another gene recurrently mutated in FL and implicated in its pathogenesis. Additional studies are needed to elucidate potential interaction between these two pathways. Despite the limitations already mentioned, the data support a genetic basis for activation of the IL-4/JAK/STAT6 axis in FL and suggest that the STAT6 mutations might collude with signals (IL-4) from the microenvironment to promote FL. Combined with the prior knowledge on the role of TFH and IL-4 in the pathogenesis of FL, the Yildiz et al study supports a rationale for therapeutic targeting of the IL-4/JAK/STAT6 axis in FL and possibly other B-cell lymphomas, such as primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and transformed FL, that harbor these mutations.5,10

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.