Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) are a group of heterogeneous clonal bone marrow disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, peripheral blood cytopenias, and potential for malignant transformation. Lower/intermediate-risk MDSs are associated with longer survival and high red blood cell (RBC) transfusion requirements resulting in secondary iron overload. Recent data suggest that markers of iron overload portend a relatively poor prognosis, and retrospective analysis demonstrates that iron chelation therapy is associated with prolonged survival in transfusion-dependent MDS patients. New data provide concrete evidence of iron’s adverse effects on erythroid precursors in vitro and in vivo. Renewed interest in the iron field was heralded by the discovery of hepcidin, the main serum peptide hormone negative regulator of body iron. Evidence from β-thalassemia suggests that regulation of hepcidin by erythropoiesis dominates regulation by iron. Because iron overload develops in some MDS patients who do not require RBC transfusions, the suppressive effect of ineffective erythropoiesis on hepcidin may also play a role in iron overload. We anticipate that additional novel tools for measuring iron overload and a molecular-mechanism–driven description of MDS subtypes will provide a deeper understanding of how iron metabolism and erythropoiesis intersect in MDSs and improve clinical management of this patient population.

Introduction

Diseases associated with iron deficiency and iron overload affect a large fraction of the world’s population. Maintaining iron balance is critical for hemoglobin synthesis. No physiologic mechanism for iron excretion exists in humans. Furthermore, diseases requiring regular red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are hampered by iron overload that, if untreated, leads to significant morbidity and mortality. The purpose of this review is to present the current state of knowledge regarding the impact of iron overload and the benefits of iron chelation on survival and erythropoiesis in patients with low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

Role of RBC transfusion in different MDS subtypes

MDS is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis. Multiple classifications are available to group MDS into prognostic subtypes based on clinical and pathologic characteristics. The current dogma suggests that all members of these classifications are clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders with a progressively increasing propensity toward transformation to acute leukemia. Refractory anemia (RA), refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (RARS), and 5q− subtypes of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification and the low or intermediate-1 subtypes of the International Prognostic Scoring System have a longer median survival and the lowest rate of progression to acute leukemia. The common biological characteristic of low-risk MDS includes a defect in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell self-renewal and differentiation, resulting in cytopenias.

Approximately 60% to 80% of patients with MDS experience symptomatic anemia, and 80% to 90% require RBC transfusions as supportive therapy.1,2 The WHO classification-based prognostic scoring system defines RBC transfusion dependence as requiring ≥1 RBC unit every 8 weeks averaged over 4 months,3 and RBC transfusion dependence correlates strongly with decreased survival in MDS patients.4 The prolonged exposure to RBC transfusions makes low-risk MDS patients most susceptible to iron overload and its clinical consequences.

Iron storage, recycling, and secondary iron overload

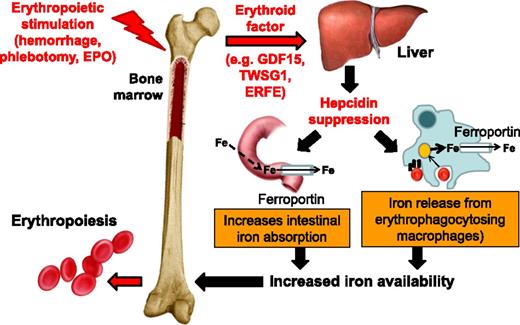

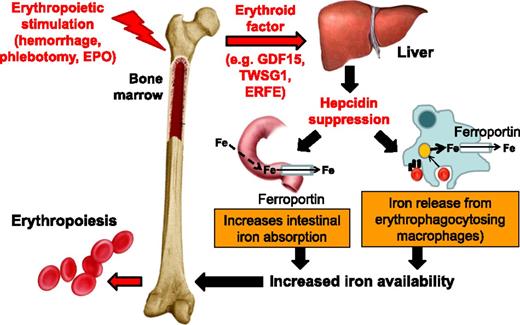

A unit of RBCs for transfusion contains 200 to 250 mg of iron released from hemoglobin as the RBCs are cleared from circulation. Iron released from reticuloendothelial cells (ie, bone marrow and spleen macrophages and Kupffer cells in the liver) is bound for storage in cytosolic ferritin or exported to plasma proteins (eg, transferrin). Present on all cells involved in iron flows (eg, macrophages, duodenal enterocytes, and hepatocytes), ferroportin is the only known iron exporter. In macrophages, ferroportin expression is transcriptionally regulated by heme5 and under translational regulation (ie, iron response elements on messenger RNA bound to iron response proteins) by iron.5-8 However, ferroportin expression is mainly regulated at the cell surface where hepcidin, a liver-derived peptide hormone, binds and leads to ferroportin internalization and degradation.9 Increased circulating hepcidin and consequent ferroportin degradation inhibit the absorption of dietary iron in the duodenum and iron release from erythrophagocytosing macrophages (Figure 1), making hepcidin the master negative regulator of iron homeostasis.10

Hepcidin regulation by erythropoiesis and its effects on iron efflux from cells involved in iron metabolism. Hepcidin plays a central role in the maintenance of iron homeostasis and regulation of plasma iron concentrations by controlling ferroportin concentrations on iron-exporting cells, including duodenal enterocytes, recycling macrophages of the spleen and liver, and hepatocytes (involved in iron storage). The bone marrow has the highest iron requirements for hemoglobin synthesis, and thus, increased erythropoietic activity suppresses hepcidin production. Several potential candidate erythroid regulators of hepcidin (eg, GDF15 and TWSG1) in β-thalassemia have been reported. Recently, a non–disease-specific mechanism has been proposed (eg, ERFE). EPO, erythropoietin; Fe, iron; TWSG1, twisted gastrulation 1.

Hepcidin regulation by erythropoiesis and its effects on iron efflux from cells involved in iron metabolism. Hepcidin plays a central role in the maintenance of iron homeostasis and regulation of plasma iron concentrations by controlling ferroportin concentrations on iron-exporting cells, including duodenal enterocytes, recycling macrophages of the spleen and liver, and hepatocytes (involved in iron storage). The bone marrow has the highest iron requirements for hemoglobin synthesis, and thus, increased erythropoietic activity suppresses hepcidin production. Several potential candidate erythroid regulators of hepcidin (eg, GDF15 and TWSG1) in β-thalassemia have been reported. Recently, a non–disease-specific mechanism has been proposed (eg, ERFE). EPO, erythropoietin; Fe, iron; TWSG1, twisted gastrulation 1.

Iron released into circulation binds transferrin with high affinity. Transferrin saturation is calculated as a ratio of serum iron to total iron-binding capacity, approximately 30% under normal conditions. When transferrin’s iron-binding capacity is exceeded, non–transferrin-bound iron (NTBI) is produced. NTBI is found after transferrin saturation exceeds 80%.11,12 Labile plasma iron is redox-active NTBI, permeates cell membranes, and causes cellular damage via production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).13,14 ROS oxidize lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, resulting in premature apoptosis, cell death, tissue and organ damage (eg, iron-overload–associated liver cirrhosis, diabetes and other endocrinopathies, and cardiomyopathy), and, if untreated, death. Transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia patients have a natural history of transfusion iron overload resulting in significant morbidity and mortality.12,15-18 Evidence of iron overload in MDS patients is mounting.19-23 However, because MDS patients present in adulthood (when propensity for comorbid diseases is high) and have a significantly shorter life expectancy, the impact of iron overload and benefit from iron chelation may be somewhat different relative to β-thalassemia patients.24

Iron requirement for and hepcidin regulation by erythropoiesis

In circulation, 2.4 g of iron is present at all times (5 L blood volume × hematocrit of 48% = 2.4 L of RBCs = 2.4 g of iron). Approximately 20 mg of iron is required daily for hemoglobin synthesis, the majority of which is recycled from senescent RBCs under the regulation of hepcidin (Figure 1). Since hepcidin’s discovery in 2000, convincing evidence suggests that erythroid suppression of hepcidin is a direct consequence of increased erythropoietic activity itself, irrespective of anemia, hypoxia, and increased erythropoietin.25,26 The observed finding of insufficient hepcidin (relative to the degree of iron overload) in diseases of expanded and/or ineffective erythropoiesis supports the predicted existence of an “erythroid factor” regulating iron metabolism.27

Multiple pieces of data suggest strongly that this erythroid factor is secreted by erythroid precursors, functioning as a hormone to suppress hepcidin expression in the liver. Several candidates have been proposed. Circulating growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) is increased in patients with several congenital and acquired anemias and correlates with concurrent low hepcidin.28 However, studies in phlebotomized mice29 and in MDS patients30 have shown poor correlation between GDF15 and hepcidin. Thus, mechanisms of hepcidin suppression may be disease specific. Recently, a potential physiological regulator of hepcidin, erythroferrone (ERFE), has been identified31 ; the authors demonstrate the loss of hepcidin suppression after phlebotomy in ERFE knockout mice, increased ERFE in mouse models of β-thalassemia, and relatively increased hepcidin expression and decreased iron overload in β-thalassemic/ERFE knockout relative to β-thalassemic mice.31 Circulating ERFE concentration in MDS patients and mouse models thereof have not yet been evaluated.

Hepcidin and iron overload in different MDS subtypes

Hepcidin levels are heterogeneous across different MDS subtypes, with a 10-fold difference between the lowest (1.43 nM in RARS) and the highest (11.3 nM in RA with excess blasts) (P = .003) concentrations. MDS subtypes remain independent predictors of hepcidin in multivariate analyses (adjusted for serum ferritin [SF] and transfusion history), suggesting that the relationship between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism differs between MDS subtypes.30

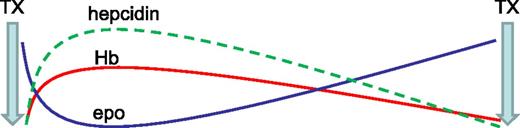

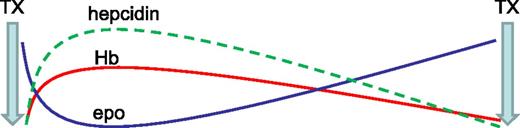

Another recent study reveals an increased hepcidin concentration in transfusion-dependent MDS patients relative to controls.32 A strong positive correlation between hepcidin and SF (r = 0.976) is observed in those receiving <9 RBC units, no correlation is observed in those receiving 9 to 24 RBC units, and a negative correlation is observed (r = −0.536) in those receiving >24 RBC units. Thus, despite the dominant regulation of hepcidin by erythropoiesis, hepcidin remains sensitive to regulation by iron in patients with relatively low RBC transfusion requirements; similar findings have been observed in β-thalassemic mice.33 RBC transfusions derepress circulating hepcidin but fall short of levels expected in response to iron overload (as measured by SF); these findings reflect prior evidence in transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia patients.34 Furthermore, hepcidin concentration is again suppressed prior to the next RBC transfusion, suggesting that erythropoiesis-mediated hepcidin suppression is proportional to the degree of erythroid expansion, highest immediately posttransfusion to lowest immediately prior to the next transfusion (Figure 2).

Model effect of erythropoiesis on hepcidin expression between RBC's transfusions. Ultimate hepcidin concentrations are the sum of effects from multiple regulators. RBC transfusions both suppress endogenous erythropoiesis and ultimately result in the accumulation of iron, released from transfused RBCs at the end of their life cycle. Thus, hepcidin is initially derepressed after RBC transfusion and progressively decreases to pretransfusion levels, mirroring hemoglobin and endogenous erythropoietin concentrations (modified from data in Ghoti et al15 ). epo, erythropoietin; Hb, hemoglobin; TX, transfusion.

Model effect of erythropoiesis on hepcidin expression between RBC's transfusions. Ultimate hepcidin concentrations are the sum of effects from multiple regulators. RBC transfusions both suppress endogenous erythropoiesis and ultimately result in the accumulation of iron, released from transfused RBCs at the end of their life cycle. Thus, hepcidin is initially derepressed after RBC transfusion and progressively decreases to pretransfusion levels, mirroring hemoglobin and endogenous erythropoietin concentrations (modified from data in Ghoti et al15 ). epo, erythropoietin; Hb, hemoglobin; TX, transfusion.

RBC transfusions are the main source of progressive iron overload in transfusion-dependent MDS patients. A person requiring 4 RBC units per month acquires approximately 9.6 g of iron per year. Because maximal daily iron absorption is 4 mg (1.4 g per year), the amount of iron acquired from RBC transfusion exceeds >sixfold that gained from gastrointestinal absorption. In contrast to other iron-overload diseases, the literature presents only 1 case report of iron overload in a transfusion-independent MDS patient with RARS,35 consistent with RARS having the lowest hepcidin levels of all MDS subcategories.

Erythroid expansion and ineffective erythropoiesis suppress hepcidin and result in iron overload in RARS patients, evidenced by their highest levels of NTBI relative to other MDS subtypes.30 In RARS patients, the magnitude of ineffective erythropoiesis is higher than in MDS-RA patients because mitochondrial iron trapping prevents normal iron incorporation into heme, resulting in low tissue oxygen tension, higher endogenous erythropoietin levels, and hepcidin suppression.30 SF3B1 gene mutations (resulting in aberrant RNA splicing) in MDS patients are associated with ringed sideroblasts, low hepcidin, and parenchymal iron overload.36-38 Between 60% and 80% of RARS patients have the SF3B1 mutation.39 Furthermore, HFE gene polymorphisms that predispose to iron overload are detected in up to 21% of MDS-RARS patients, significantly higher than in other MDS subtypes (9%).40,41 These data suggest that multiple factors, including hepcidin, increase the burden of iron overload in RARS patients and that this MDS subtype may be different from other low-risk transfusion-dependent MDS patients in whom transfusional iron is the main cause of iron overload.

Effects of iron overload on erythropoiesis

Iron chelation results in improved hemoglobin and reduced RBC transfusion requirements,42,43 suggesting that iron overload impedes erythropoiesis. However, the mechanisms by which this occurs are not completely understood. Iron overload inhibits burst-forming unit colony formation and erythroblast differentiation of both murine and human hematopoietic progenitors in vitro, and cells exposed to excess iron exhibit dysplastic changes with increased intracellular ROS and decreased BCL-2 (antiapoptotic gene) expression.44 Furthermore, the addition of ferrous ammonium sulfate to peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from MDS patients resulted in increased ROS, oxidation of 8-oxoguanine, and an abnormal comet assay consistent with DNA damage.45 Reduced BCL-2 and increased ROS in the cell together cause the leakage of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm, triggering apoptosis by activated caspase-9.46

MDS patients with elevated SF have significantly fewer burst-forming units,47 even when SF is minimally elevated (>250 μg/L). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming units showed no significant difference between the 2 groups, suggesting that erythroid progenitors are more susceptible to iron overload than myeloid progenitors.47 Erythroid precursor susceptibility likely results from impaired heme synthesis and mitochondrial iron trapping, observed in RARS patients, and is reminiscent of primary diseases associated with impaired heme synthesis (eg, porphyria and congenital sideroblastic anemia). Because of this similarity and the known disease exacerbation in the presence of iron overload and improvement with iron chelation, it is reasonable to expect that iron depletion is beneficial for erythropoiesis in iron-overload diseases.48 Data from multiple sources, including our laboratories, reveal that iron restriction improves erythropoiesis in β-thalassemia, a disease characterized by ineffective erythropoiesis similar to MDS.49-53 Recent data suggest that in addition to causing relative iron deficiency and reversal of ineffective erythropoiesis in mouse models of β-thalassemia, the extracellular domain of activin receptor IIa results in ligand trapping of GDF11.54 Furthermore, the extracellular domain of activin receptor IIb also results in ligand trapping of GDF11 and has been shown to reverse anemia and ineffective erythropoiesis in a mouse model of MDS.55 Thus, the impact of iron overload on erythropoiesis may be mediated through GDF11, a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily.

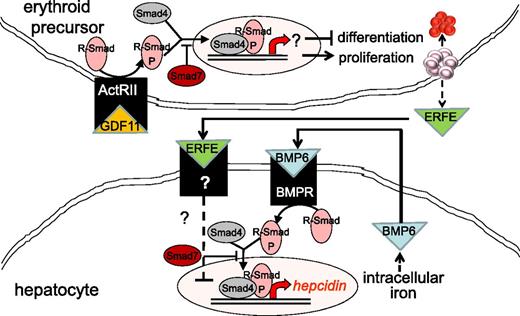

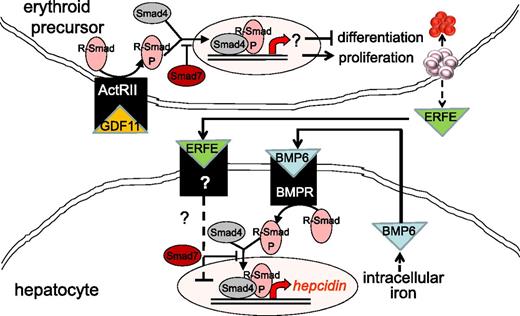

Increased TGF-β has been implicated in the pathophysiology of MDS. In a recent study, the authors report increased serum GDF11 concentration in MDS relative to age-matched controls.55 As signal transduction following TGF-β receptor binding results in the phosphorylation of Smad proteins, Smad2 is heavily phosphorylated in MDS bone marrow progenitors and is found to be upregulated in CD34+ cell from MDS patients.56 Furthermore, Smad7, a negative regulator in the Smad complex, is markedly decreased in MDS and leads to further increased TGF-β signal transduction (Figure 3).57 Consequently, more complete understanding of the importance of TGF-β is beginning to emerge.

Model of crosstalk between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism involving TGF-β family member GDF11. Erythroid precursor proliferation and differentiation is regulated in part by multiple members of the TGF-β family. GDF11 binding to ActRII results in Smad2,3 phosphorylation and leads to the expansion of erythroid precursors and suppresses differentiation, resulting in ineffective erythropoiesis and iron overload. Hepcidin expression in hepatocytes is stimulated through the iron pathway (through bone morphogenic protein receptor signaling and Smad1,5,8 phosphorylation) and suppressed through the erythropoiesis pathway (possibly through ERFE binding and signaling through a yet-unidentified receptor). ActRII, activin receptor IIa; BMP6, bone morphogenic protein 6; BMPR, bone morphogenic protein receptor; GDF11, growth differentiation factor 11; R-Smad, receptor-mediated decapentaplegic protein; R-Smad-P, phosphorylated R-Smad.

Model of crosstalk between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism involving TGF-β family member GDF11. Erythroid precursor proliferation and differentiation is regulated in part by multiple members of the TGF-β family. GDF11 binding to ActRII results in Smad2,3 phosphorylation and leads to the expansion of erythroid precursors and suppresses differentiation, resulting in ineffective erythropoiesis and iron overload. Hepcidin expression in hepatocytes is stimulated through the iron pathway (through bone morphogenic protein receptor signaling and Smad1,5,8 phosphorylation) and suppressed through the erythropoiesis pathway (possibly through ERFE binding and signaling through a yet-unidentified receptor). ActRII, activin receptor IIa; BMP6, bone morphogenic protein 6; BMPR, bone morphogenic protein receptor; GDF11, growth differentiation factor 11; R-Smad, receptor-mediated decapentaplegic protein; R-Smad-P, phosphorylated R-Smad.

Comparison of available methods to measure iron overload

Various noninvasive methods of measuring iron overload exist, including SF, NTBI, labile plasma iron, and liver iron concentration (LIC) as determined by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) R2*, biomagnetic liver susceptometry, and cardiac T2* MRI. Invasive methods include liver and heart biopsies. In general, ubiquitous access to noninvasive methods has replaced biopsy as the standard method for measuring tissue iron concentrations in most centers. However, due to lack of consensus on the timing and utility of measuring the degree of, screening for, and diagnosing iron overload in MDS, the pros and cons of these markers and methods are discussed.

SF

A study in transfusion-naive newly diagnosed MDS patients reveals that patients with SF <500 ng/mL survive longer than those with SF >500 ng/mL (118.8 vs 10.2 months; P = .002),58 with significantly longer leukemia-free survival. In addition, SF independently predicts survival and risk of leukemia in MDS in multivariate analyses when transfusion dependence and iron overload are used as corrected time-dependent covariates.59 These studies indicate that excess iron is potentially harmful in MDS patients. Although some authors have questioned the utility of SF because of its increase in systemic inflammatory conditions as an acute-phase reactant, others assert that determining an individual’s SF/LIC ratio enables its use for further follow-up and monitoring of iron overload, especially when other markers of inflammation (eg, C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate) are also assessed.60 Despite its limitation, SF remains a valuable tool for monitoring iron overload given its ubiquitous availability, low cost, and well-standardized measures. However, more direct measures of iron stores are now available and required to establish diagnosis, estimate prognosis, and assess impact of treatment in patients with complex iron-overload syndromes (ie, transfusion-dependent MDS patients). These are discussed below.

LIC

LIC is the reference standard to estimate body-iron stores.61 Although normal LIC is estimated at 1.5 to 2 mg/g dry weight, high LIC (>15-20 mg/g dry weight) correlates with hepatic dysfunction,20 hepatic fibrosis,62 and worse overall prognosis.63 As high accuracy of noninvasive measures has been achieved, LIC is measured by noninvasive methods (eg, MRI), and biopsy use is secondary at most centers. Among the noninvasive methods, MRI is widely available and less expensive. The MRI R2 and R2* techniques demonstrate an average sensitivity of >85% and specificity of >92% and can be applied at any center with a reasonably new MRI machine, providing a rapid and accurate method for estimating LIC to diagnose and manage iron overload.64 MDS patients have a high prevalence of liver iron loading, with R2* >158.7 Hz in 35 out of 43 (81%) patients.23 In one study, liver R2* was positively correlated with RBC transfusion frequency (r = 0.72, P < .0001) and SF (r = 0.53, P < .0001),23 but in another study, liver T2* showed no correlation with RBC transfusion frequency (r = 0.19; P = .57) or with SF (r = −0.09; P = .77).20 Chelated MDS patients had a trend toward lower LIC (median 5.9 mg/g dry weight; range 3.0-9.3 mg/g dry weight) than unchelated MDS patients (median 9.5 mg/g dry weight; range 3.0-14.4 mg/g dry weight) (P = .17).20 Although all patients received RBC transfusions, not all those analyzed were low/intermediate-1–risk MDS, and because some received iron chelation and only a small number of patients was assessed in total, reliable conclusions regarding the natural history of iron overload or effectiveness of iron chelation in low/intermediate-1–risk MDS patients is not possible in this study.

NTBI and labile plasma iron

NTBI, measured by spectrophotometry, is significantly higher in low-risk relative to high-risk MDS.65 Tissue damage in iron-overload diseases is thought to result from the increased uptake of labile plasma iron leading to increased intracellular labile iron.66 Labile plasma iron >0.4 μM is highly correlated with iron overload.13 Labile plasma iron in β-thalassemia patients is undetectable during the course of deferoxamine infusion and peaks prior to the next infusion.67 These data suggest that labile plasma iron levels may aid in determining the efficacy of iron chelation therapy and provide more immediate evidence about iron overload to support decisions to change iron chelation dosing. Several means of measuring labile plasma iron have been proposed, but few laboratories have established an accurate and reproducible methodology at this time.

Cardiac T2* MRI

Heart failure is the primary cause of death in severe iron overload.68,69 Cardiac T2* MRI provides an accurate assessment of cardiac iron overload,70 correlating well with left ventricular function71 but poorly with SF and LIC, indicating that iron loading and clearance are differently regulated in the heart relative to the liver.70 Although cardiac complications account for the majority of nonleukemic death in low-risk MDS patients,4 there is insufficient evidence that these complications result from cardiac iron overload.20-22 Only one study using cardiac T2* MRI in MDS patients found that, despite 13% on iron chelation therapy, 19% (8/43) of patients demonstrated evidence of myocardial iron overload (R2* >50 Hz), which correlates with longer transfusion history.23 Although these retrospective studies include low-risk transfusion-dependent MDS patients with significantly elevated SF and evidence of iron overload in the liver, most patients evaluated were already receiving chelation therapy and had no symptoms or signs of heart failure. Prospective evaluation of cardiac T2* MRI in low-risk transfusion-dependent MDS patients is needed to clarify the relationship of frequent transfusion, systemic iron overload, and heart failure in this patient population (Table 1).

Taken together, evaluation of iron overload in MDS is complex and requires multiple assessment methods to properly evaluate potential clinical risk and impact of therapy. SF is relatively nonspecific and, like transferrin saturation, is only clinically relevant for diagnosis of iron overload at very high values (ie, SF >2500 ng/mL and transferrin saturation >70%). However, using changes in these easily available methods to evaluate the efficacy of iron chelation remains appropriate. Finding labile plasma iron present in transfusion-dependent MDS patients is always pathological, warranting iron chelation therapy. The end-point goal of all therapy is to return patients to undetectable labile plasma iron; 0.4 µM is the lower limit of detectable in the standardized currently commercially available FeROS assay (Afferix, Ashkelon, Israel) previously used in studies with iron-overloaded patients.72 Elevated LIC (measured by liver T2* MRI) and below-normal cardiac T2* MRI strongly suggest parenchymal iron overload, warranting iron chelation therapy when cardiac iron overload is identified even in mild forms (eg, cardiac T2* <20 ms) because of the length of time it takes to remove iron from the heart. Trigger to initiate iron chelation in response to LIC measurement is more flexible, and although normal LIC is <1.2 mg Fe/g dry weight, iron chelation can be initiated when LIC reaches 3 mg Fe/g dry weight. As multiple novel methods for measuring iron-related parameters become standardized and applied to MDS in larger and prospective studies, a more robust understanding of differences between patients will further aid clinicians managing iron overload in MDS patients.

Clinical impact of iron chelation in MDS patients

Iron overload reduction and survival benefit

Uni- and multivariate analyses of MDS patients demonstrate that every 500-μg/L increase in SF >1000 μg/L is associated with a 1.36-fold increase in death.4 The increased mortality extended to low-risk MDS patients with RA, RARS, and 5q−, with a trend toward statistical significance between SF and mortality in RCMD patients and poor correlation in patients with RA with excess blasts. Additional studies corroborate these findings.73 However, one recent retrospective study showed that neither the number of RBC transfusions nor SF has a statistically significant effect on overall survival in RARS patients.74 We anticipate that serum hepcidin, particularly in RARS, and liver T2* MRI, more broadly in MDS, will provide more clarity to the association between iron overload and overall survival.

By demonstrating survival benefit, retrospective studies of iron-overloaded MDS patients receiving iron chelation therapy further support the premise that iron overload is an independent predictor of mortality. A study in low-risk MDS demonstrates a significant difference in median survival with iron-chelated vs nonchelated patients (160 months vs 40.1 months, respectively). Significantly more low-risk MDS patients receiving iron chelation survive up to 4 years (80% vs 44%; P < .03).75 Another study in low-risk MDS patients shows a median survival of 124 vs 53 months in the chelated and nonchelated groups, respectively (P < .0003).76 However, as in all retrospective studies, selection bias is an important potential confounder.

Multiple studies suggest that iron chelation inhibits the consequences of iron overload in MDS patients. Deferasirox (Exjade) decreases SF, labile plasma iron, and LIC in a dose-dependent manner despite ongoing RBC transfusions77-79 in transfusion-dependent MDS patients.80 Furthermore, treatment with deferasirox in iron-overloaded MDS patients increases serum and urinary hepcidin, likely by reducing iron overload and the inhibitory effect of ineffective erythropoiesis on hepcidin.81 Lastly, deferasirox also reduced cardiac iron concentration and cardiac myocyte superoxide levels.82

The EPIC (Evaluation of Patients’ Iron Chelation with Exjade) trial, the largest cohort of MDS patients using deferasirox, demonstrates a significant decrease in median SF at 1 year, but of significant concern is the 49% discontinuation rate due to renal and gastrointestinal side effects.83 Additional studies corroborate this relatively low rate of compliance due to side effects.84,85 An ongoing multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, TELESTO, to evaluate the effect of deferasirox on low-risk MDS patients with iron overload, is underway. This trial intends to evaluate death and nonfatal events related to cardiac and liver function,86 but, due to sustained difficulties with patient recruitment, the results may not be sufficiently powered to definitively answer these questions.

Prior to the approval of deferasirox, deferiprone (L1) was the only oral iron chelator available for clinical use outside of the United States; recent Food and Drug Administration approval of deferiprone has stimulated discussion and data analysis on its relative effectiveness. Profound granulocytopenia has been reported as the most severe adverse effect and thus limited the use of deferiprone to treat iron overload in MDS patients.87-89 Furthermore, use of deferiprone in low-risk MDS patients reveals the greatest utility in patients with relatively low SF and RBC transfusion requirements.90 A retrospective study comparing deferasirox with deferiprone in transfusion-dependent low-risk MDS patients with iron overload confirmed the superior efficacy and milder side effect profile of deferasirox in this patient population.89 However, several important details are missing, namely the degree of compliance with iron chelation therapy as well as the fraction of patients receiving the indicated dose of deferiprone (75 mg/kg per day), to determine deferiprone’s efficacy and properly interpret these results.

Although no universally accepted guidelines currently exist, both National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and MDS Foundation recommendations are available (Table 2).91,92 The guidelines focus on avoiding harm from iron overload in otherwise-healthy, “low-risk,” transfusion-dependent MDS patients with elevated SF or evidence of organ iron overload (eg, liver T2* MRI). The recommendations for monitoring iron load and initiation of iron chelation include a baseline SF and liver T2* MRI and then follow-up studies (eg, every 3-4 months in transfusion-dependent patients) based on the rate of RBC transfusion. Although MRI is a well-established measure of organ iron deposition, it is not yet routinely used the way we use elevated SF, which by itself is insufficiently sensitive to inform when to initiate or how to monitor therapeutic effectiveness in MDS patients.

These guidelines suggest that although benefit from iron chelation has not been clearly delineated, a strong consensus on the need to avoid iron overload is evident and needs to be balanced against potential side effects of iron chelation therapy. Deferoxamine, which because of its short half-life needs to be given parenterally, is relatively inconvenient, negatively impacting compliance,72 and is associated with injection site reactions as well as potential ocular and otic toxicity requiring monitoring. Side effects of the oral iron chelators mentioned above have resulted in cessation of treatment in a significant proportion of patients.84,87-89 Lastly, the benefit of iron chelation on quality of life may be more difficult to assess in light of the multiple comorbidities in many MDS patients.94 However, because transfusion dependence decreases quality of life,94-96 reversal of transfusion-induced iron overload or transfusion dependence as a consequence of iron chelation may result in quality-of-life improvements.

Iron chelation and improved erythropoiesis in MDS

The question remains whether iron chelation prevents iron-induced ROS, consequent oxidation of nucleotides (eg, 8-oxoguanine), and resultant mutations.97 In vitro experiments in trisomy 8 MDS patient cells demonstrate that iron chelation induces cell differentiation.98 In another report, MDS patients’ peripheral blood mononuclear cells treated with ferrous ammonium sulfate increased ROS and 8-oxoguanine oxidation and resulted in an abnormal comet assay consistent with DNA damage; all these findings were reversed with the addition of iron chelator.45 In addition, iron chelation induces differentiation of several human myeloid cell lines (eg, HL60 and NB4) and MDS patients’ peripheral blood–derived CD34+ cells. Taken together, iron chelation in MDS patients ameliorates pathological effects of iron overload and consequent oxidative stress by decreasing iron-induced cytotoxicity, DNA damage, blocked differentiation in hematopoietic cells, and possibly transformation to leukemia.

Iron chelation improves ineffective erythropoiesis in MDS patients. The majority of deferoxamine (Desferal)-chelated MDS patients reduce RBC transfusion requirements by 50% and 46% became completely transfusion independent.99 Other studies in deferasirox-chelated MDS patients also observe reduced RBC transfusion requirements.100-102 In one study, 16% of patients achieved transfusion independence by 12 months with a median hemoglobin of 8 g. In this study, all patients reduced RBC transfusion frequency by 67% after 12 months of treatment.85 Most recently, chelation with deferasirox demonstrated a 1.5- to 1.8-g/dL increase in hemoglobin despite a decrease in RBC transfusion requirements in patients with low-risk MDS.103

Conclusions and recommendations

Iron overload in low-risk MDS is an important clinical problem resulting from RBC transfusions to correct the anemia. Despite its potential impact, hepcidin appears to play a relatively minor role in iron overload compared with frequent RBC transfusions in transfusion-dependent MDS patients. However, in some transfusion-independent low-risk MDS patients (eg, RARS), increased erythropoietic activity results in hepcidin suppression and contributes to iron loading. It may therefore be prudent to monitor transfusion-independent RARS patients for iron overload.

The most appropriate direct method to diagnose iron overload is T2* MRI (ie, liver and heart). Furthermore, circulating NTBI and labile plasma iron concentration are becoming more available and have been used in several clinical studies. Currently, the recommendation to initiate iron chelation therapy in MDS patients is based on the total number of RBC transfusions and on elevated SF in transfusion-dependent patients. Because different patients undergo relatively different rates of parenchymal iron loading and different volume loss from blood sampling for diagnostic testing, liver T2* MRI is the most reasonable and objective measure to evaluate iron overload and would be reasonably assessed after 20 RBC units have been transfused. Although insufficiently sensitive or specific to diagnose iron overload, changes in SF and transferrin saturation are still useful measures of therapeutic efficacy of iron chelation in iron-overloaded patients.

NCCN guidelines mention hemoglobin of 10 g/dL as a reasonable and well-accepted goal of RBC transfusion in MDS (and in general),92 and transfusion dependence is reasonably defined in our view as requiring at least 2 RBC units per month for at least 1 year. This results in the delivery of at least 24 RBC units and 6 g of iron. In our view, once 20 RBC units have been transfused, even if <1 year has passed, evaluation for iron overload is warranted if the patient is expected to continue chronic RBC transfusion therapy.

Evidence from managing patients with β-thalassemia suggests that it is appropriate to start iron chelation when T2* MRI results are above the equivalent of LIC 3 to 4 mg/g dry weight105 and certainly if any evidence of cardiac iron overload is identified. As chronically transfused iron chelated patients with β-thalassemia are followed with annual T2* MRI to determine effectiveness of therapy, need for dose adjustments, and chelation holidays,105 low-risk MDS patients who receive chronic RBC transfusions can be managed similarly. Low-risk MDS patients with relatively lower RBC transfusion requirements may be considered for T2* MRI after every additional 10 to 20 RBC units to evaluate the need to initiate iron chelation, determine effectiveness of therapy, or the need for dose adjustments. Once iron chelation therapy is initiated, tests to monitor associated side effects should be performed. MDS patients on deferasirox should be assessed monthly for serum creatinine, bilirubin, aminotransferases, and complete blood count.105 Similar recommendations are appropriate for MDS patients treated with deferiprone, although insufficient data make practical recommendations premature.

The rationale for iron chelation therapy in MDS remains compelling but has not been tested in prospective randomized studies. Considerable evidence suggests that iron chelation decreases SF, LIC, and labile plasma iron. Data from multiple independent retrospective studies demonstrate that iron chelation therapy results in a marked survival benefit in low-risk MDS patients. Results of an ongoing double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial are anticipated to provide additional survival and morbidity data. However, in view of the serious adverse effects of iron overload, it is reasonable to offer iron chelation therapy to low-risk MDS patients at high risk for developing iron overload.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend sincere appreciation to E. Nemeth (University of California, Los Angeles) for evaluation and contribution to the coherence of the figures.

Authorship

Contribution: N.S. wrote and edited the article; N.V. wrote the article; E.R. edited the article and figures; A.V. edited the article and figures; and Y.G. wrote and edited the article and figures.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yelena Ginzburg, Erythropoiesis Laboratory, Lindsley F. Kimball Research Institute, New York Blood Center, 310 East 67th St, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: yginzburg@nybloodcenter.org.