Key Points

Loss of Id2 in T cells results in overexpression of IL-10 during influenza infection and GVHD and protects against GVHD immunopathology.

Id2 represses the direct E2A-mediated activation of the Il10 locus in effector T cells.

Abstract

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a key immunoregulatory cytokine that functions to prevent inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Despite the critical role for IL-10 produced by effector CD8+ T cells during pathogen infection and autoimmunity, the mechanisms regulating its production are poorly understood. We show that loss of the inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2) in T cells resulted in aberrant IL-10 expression in vitro and in vivo during influenza virus infection and in a model of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Furthermore, IL-10 overproduction substantially reduced the immunopathology associated with GVHD. We demonstrate that Id2 acts to repress the E2A-mediated trans-activation of the Il10 locus. Collectively, our findings uncover a key regulatory role of Id2 during effector T cell differentiation necessary to limit IL-10 production by activated T cells and minimize their suppressive activity during the effector phase of disease control.

Introduction

The development of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains a major limitation in the therapeutic success of bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of hematologic malignancies and immune deficiencies. GVHD arises as a result of damage to host tissues mediated substantially by conventional T cells. The molecular machinery that regulates whether these T cells develop a destructive effector phenotype that drives GVHD or a suppressive phenotype that limits inflammation remains unclear, although genetic evidence suggests that interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a important mediator of protection.1-3

IL-10 is also a crucial regulator of the adaptive immune response. Temporal expression of IL-10 must be tightly controlled throughout the course of pathogen infection to balance the protective and destructive impact of this cytokine on disease outcome. During an acute primary viral infection, the release of IL-10 by effector CD8+ T cells is essential for host survival, acting to dampen inflammation by limiting tissue damage and pathogen replication while enabling immune cells to effectively eliminate the pathogen.4,5 In contrast, other pathogens are able to exploit IL-10 to suppress immunity and establish chronic infection.6,7 Despite the importance of IL-10 produced by T cells in infectious and inflammatory disease, the factors that control IL-10 expression are poorly understood.

The regulation of Il10 expression in T cells is complex and depends on a number of different transcriptional regulators. In CD4+ T cells, the transcription factors c-Maf, B lymphocyte induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1), interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4), basic leucine zipper transcription factor, aryl hydrocarbon receptor, nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), nuclear factor interleukin 3 regulated, ETS-related gene 2, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) positively regulate Il10 expression.8-15 Much less is known about the regulation of Il10 expression in CD8+ T cells. Blimp-1 has been shown to be important for IL-10 production by CD8+ T cells in vivo following influenza infection,14 but the role of other transcriptional regulators of peripheral CD8+ T cell differentiation has not been examined in detail. Inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2) is a transcriptional regulator required for effector T-cell differentiation.16-18 Loss of Id2 drives CD8+ T cells to adopt a memory phenotype marked by increased expression of the transcription factors Eomes and Tcf7.17 Id2, like other inhibitor of DNA binding proteins, lacks a DNA binding domain but is capable of binding various members of the E protein family of transcription factors such as E2A splice variants E12 and E47, HEB, and E2-2 to form heterodimers.19 Thus, the formation of Id/E protein complexes is thought to inhibit E protein transcription and act to fine-tune the transcriptional networks regulated by E proteins.

In the present study, we investigated how Id2 influences cytokine production in effector T cells. We discovered that Id2 is a key negative regulator of Il10 expression in cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and, to a lesser degree, in CD4+ T cells. Loss of Id2 in T cells resulted in the increased generation of IL-10–producing T cells during influenza virus infection and GVHD and impaired the ability of T cells to induce destructive pathology associated with GVHD. We show that Id2 repressed IL-10 production in CD8+ T cells by inhibiting the E2A-dependent activation of the Il10 locus. Moreover, our data indicate that E2A and IRF4 can collaborate to induce the trans-activation of the conserved noncoding sequence (CNS) 9 enhancer of the Il10 locus. Collectively, this work highlights the unique function of Id2 in regulating IL-10 production in effector T cells.

Materials and methods

Mice

Id2fl/flLckCre,17,20 OT-I,21 LckCre,22 C57BL/6 (Ly5.2+), Il10gfp/+ B6.129S6-Il10tm1Flv/J,23 Irf4−/−,24 B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (Ly5.1+), BALB/c, and Ly5.1 × Ly5.2 (F1) mouse lines have been previously described. All mice were used at 6 to 8 weeks and were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with the guidelines of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research Animal Ethics Committee.

Viral infections

Mice were anesthetized with methoxyflurane and then inoculated with 104 plaque-forming units (PFU) of the HKx31 (H3N2) influenza virus. Memory mice were generated by priming with an intraperitoneal injection of 107 PFU of A/PR/8/34 (PR8) influenza virus.25 Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed by gently flushing 2 × 500 μL of phosphate-buffered saline through a catheter inserted into the trachea of killed mice.

Generation of bone marrow chimeras

Mixed bone marrow chimeras were established by reconstituting lethally irradiated (2 × 0.55 Gy) Ly5.1+ or Ly5.1 × Ly5.2 (F1) recipient mice with a mixture of Id2fl/flLckCre+ (3.5 × 106) and wild-type (Ly5.1+, 1.6 × 106) T-cell–depleted bone marrow cells and allowed to reconstitute for 6 to 8 weeks.

T-cell isolation

T cells were enriched from spleen and lymph nodes as previously described.17 Lymphocytes were isolated from colon lamina propria as previously described.26 Liver-infiltrating lymphocytes were isolated by centrifugation liver cell suspension on a 33.75% isotonic Percoll (GE Healthcare Biosciences) density gradient for 12 minutes at 693g at room temperature.

Induction of GVHD

A total of 2.5 to 5 × 106 T-cell–depleted C57BL/6 or Ly5.1+ bone marrow cells were injected with or without 0.5 to 1 × 106 wild-type or Id2-deficient T cells into lethally irradiated (2 × 5 Gy) BALB/c recipient mice. Bone marrow was depleted of T cells as previously described.17 Following bone marrow transfer, clinical symptoms and weigh were monitored daily. For the in vivo blocking of IL-10 receptor (IL-10R), 1 mg of IL-10R blocking antibody (clone 1B1.3A1) or control antibody (HRPN) (BioXcell) was injected intraperitoneally 4 days after T-cell transfer.

Cell-surface staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis

Virus-specific CD8+ T cells were detected by staining with phycoerythrin-coupled tetrameric H-2b major histocompatibility class (MHC) I complexes loaded with epitopes of influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP; H-2Db-restricted NP366-374).25

Retroviral constructs

E12 and E47 (Addgene plasmid 34585, deposited by Dr C. Nelson) complementary DNAs were subcloned into the MSCV-V5-IRES-Cherry between the site EcoRI (5′-ter) and XhoI (3′-ter) in frame with the V5 tag. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) Tcfe2a-IRES-GFP and shRNARenilla-IRES-GFP (control short hairpin) LMP vectors were previously described.17

Retroviral transduction of OT-I CD8+ T cells

Id2fl/flLckCre+ or wild-type CD8+ OT-I T cells were enriched from the spleen and cultured in complete RPMI containing human rhIL-2 (30 U/mL) and 1 μg/mL ovalbumin (OVA)257-264 peptide for 1 to 2 days. Retroviral supernatant was then spun for 1 hour at 4000 rpm at 4°C in plates coated with 32 μg/mL of RetroNectin. Retrovirus supernatant was then removed, and OT-I T cells were added together with polybrene (1 μg/mL) in complete RPMI for 1 day. OT-I cells transduced with the shRNATcfe2a-IRES-GFP LMP or ShRNARenilla-IRES-GFP LMP retroviruses were selected in puromycin at 2 μg/mL for 5 to 7 days.

Intracellular flow cytometry staining

CD8+ T-cell–enriched splenocytes from virus-infected mice or in vitro–activated OT-I CD8+ T cells were stimulated for 5 hours with media alone, 1 μg/mL NP366-374 peptide, or OVA257-264 peptide in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences). Polyclonal CD8+ T cells were stimulated in vitro with PMA (50 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and ionomycin (0.66 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 hours in the presence of Golgistop (BD Biosciences). Cells were then washed, fixed, and stained with anti-interferon-γ (XMG1.2) and IL-10 (JES5-16E3, BD Biosciences) for analysis.

For detection of intracellular phospho-STAT3, 4, and 5, CD8+ T cells were cultured at 5 × 105 cells per mL in anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody coated (2 μg/mL) in complete RPMI medium in presence of anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody (2 μg/mL) for 2 days in the presence of rhIL-2 (30 U/mL). Cells were then rested overnight at 5 × 105 cells per mL in absence of cytokine. The day after, cells were washed in complete medium and incubated for 1 hour with recombinant mouse IL-12 (5 ng/mL; Peprotech), IL-21 (50 ng/mL; Peprotech), or IL-2 (100U/mL) before fixation followed by staining with anti-pSTAT3 (pY705) or pSTAT4 (pY693) using the phosphoFlow Kit (BD Biosciences).

Microarray analysis

DbNP366-specific CD8+ T cells were purified by flow cytometric sorting (FACS Aria flow cytometer, BD Biosciences) from day 9 HKx31-infected PR8-primed Id2gfp/gfp or Id2fl/flLckCre+/Ly5.1+/+ mixed bone marrow chimeras.17 DNA microarray analysis of gene expression was performed as previously described.17 The Gene Expression Omnibus referenced accession numbers for these data are GSE44140 and GSE44141.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was prepared from purified DbNP366-specific CD8+ T-cell populations using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using the SensiMix SYBR no-Rox kit (Bioline). Analyses were done in triplicate, and mean normalized expression was calculated with Hprt as the reference gene. Nfil3 quantification was performed using Nfil3 TaqMan primers and TaqMan reagents from Applied Biosystems.

Primer sequences were as follows: Il10: forward 5′-GAAGACCCTCAGGATGCGG-3′, reverse 5′-CCTGCTCCACTGCCTTGCT-3′; Prdm1: forward 5′-TTCTCTTGGAAAAACGTGTGGG-3′, reverse 5′-GGAGCCGGAGCTAGACTTG-3′; Irf4: forward 5′- GCCCAACAAGCTAGAAAG-3′, reverse 5′- TCTCTGAGGGTCTGGAAACT-3′; c-Maf: forward 5′- TTCCTCTCCCGAATTTTTCA-3′, reverse 5′- GCAACAAGGAGCGAATAAGC-3′.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Histone chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was performed on 5 to 10 × 106 wild-type or Id2-deficient OT-I cells per experiment using polyclonal antibody to histone H3 acetylated at Lys27 or to histone H3 trimethylated at Lys27 (all from Millipore). Quantitative PCR was used for analysis of enrichment.13 Reactions were done in duplicate using SensiMix SYBR no-Rox kit (Bioline).

Reporter assay

The CNS-9/IL-10 minimal promoter reporter construct was generated by cloning the CNS-9 fragment of the Il10 locus into the pXPG luciferase vector containing 79 bp of the Il10 minimal promoter.15 NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with the pXPH CNS-9/IL-10 minimal promoter vector in the presence or absence of vectors encoding IRF4, E47, or a mock vector together with a plasmid encoding Renilla luciferase using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours after transfection, luciferase activity was assessed by the dual-luciferase assay system (Promega).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Prism software Student t test for comparison of groups of samples of equal variance, Mann-Whitney U test to compare groups of samples with significantly different variance, and log-rank test for statistical assessment of survival.

Results

Loss of Id2 results in enhanced IL-10 expression in effector CD8+ T cells

Loss of Id2 results in a T-cell–intrinsic defect in effector CD8+ T-cell differentiation,17,18 but it is not known how this dysregulation impacts on the immune pathology associated with acute viral infection. To investigate this question, we made use of our conditional knockout mouse in which the Id2 coding region is specifically deleted in T cells through LckCre-mediated deletion (Id2fl/flLckCre+). In contrast to expectation, we found that following infection with HKx31 influenza virus, Id2fl/flLckCre+ mice showed reduced weight loss compared with wild-type mice (Figure 1A), suggesting a decreased inflammatory response caused by acute influenza virus infection. Consistent with this, the expression of the inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IL-1β were reduced in the bronchoalveolar fluid of Id2fl/flLckCre+ (Ly5.2+/+):wild-type Ly5.1+/+ mixed bone marrow chimeras compared with control wild-type Ly5.2+/+:Ly5.1+/+ mixed bone marrow chimeras (Figure 1B).

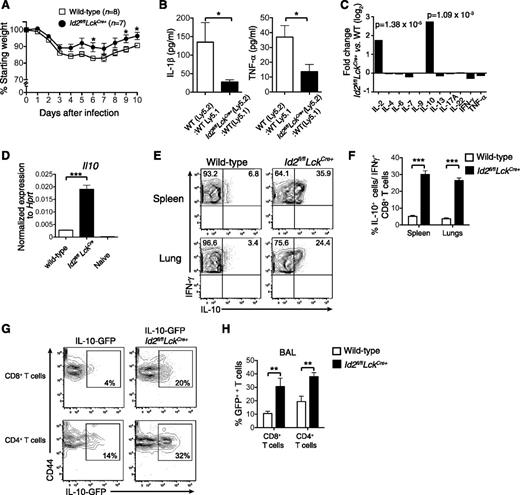

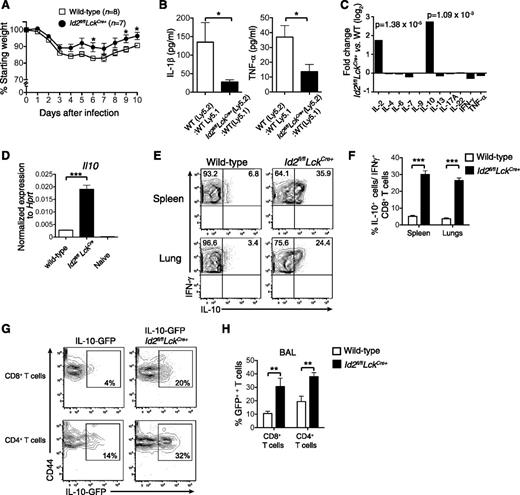

Id2 represses IL-10 expression by virus-specific CD8+ T cells. (A) Weight loss in wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ mice infected intranasally with 104 PFU HKx31 influenza virus. Data show mean weight ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; *P < .05. (B) Quantification of IL-1β and TNF-α in the bronchoalveolar fluid of mixed bone marrow chimeras in Id2fl/flLckCre+ (Ly5.2+):wild-type (Ly5.1+) → wild-type F1 (Ly5.2+Ly5.1+) or wild-type (Ly5.2+):wild-type (Ly5.1+) → wild-type F1 (Ly5.2+Ly5.1+) 8 days after infection with HKx31 (n = 6 from 2 independent experiments). Statistically significant differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test (TNF-α) or a Mann-Whitney U test (IL-1β); *P < .05. (C) Microarray analysis of DbNP366-specific Id2fl/flLckCre+ and wild-type CD8+ T cells isolated from the spleen of PR8-primed/HKx31-infected mixed bone marrow chimeric mice. Data show the mean fold difference of genes from 3 biologically independent analyses. (D) Quantitative analysis by real-time PCR of Il10 mRNA from wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ DbNP366-specific (KLRG1−) CD8+ T cells from PR8-primed/HKx31-infected mixed bone marrow chimeras (day 9) and naïve CD44−CD62L+ CD8+ splenic T cells. Data show the mean Il10 expression ± SEM relative to Hprt from 3 independent samples. (E-F) Intracellular expression (E) and frequency (F) of IL-10 in IFN-γ+Id2fl/flLckCre+ (Ly5.2+) or wild-type (Ly5.1+) CD8+ T cells isolated from the spleen and the lung of PR8-primed mixed bone marrow chimeras 9 days after infection with HKx31. Data show the mean ± SEM (spleen, n = 11; lung, n = 9 mice per genotype pooled from 3 independent experiments). (D,F) Statistically significant differences were determined using a 2-tailed paired Student t test; ***P < .001. (G-H) IL-10-GFP expression (G) and frequency (H) in Id2fl/flLckCre+ (Ly5.2+) or wild-type (Ly5.1+) CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from the bronchoalveolar lavage from mixed bone marrow chimeras 9 days after infection with HKx31. (H) Data show the mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice per genotype pooled from 2 independent experiments). Statistically significant differences were determined using a Mann-Whitney U test; **P < .01. WT, wild-type.

Id2 represses IL-10 expression by virus-specific CD8+ T cells. (A) Weight loss in wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ mice infected intranasally with 104 PFU HKx31 influenza virus. Data show mean weight ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; *P < .05. (B) Quantification of IL-1β and TNF-α in the bronchoalveolar fluid of mixed bone marrow chimeras in Id2fl/flLckCre+ (Ly5.2+):wild-type (Ly5.1+) → wild-type F1 (Ly5.2+Ly5.1+) or wild-type (Ly5.2+):wild-type (Ly5.1+) → wild-type F1 (Ly5.2+Ly5.1+) 8 days after infection with HKx31 (n = 6 from 2 independent experiments). Statistically significant differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test (TNF-α) or a Mann-Whitney U test (IL-1β); *P < .05. (C) Microarray analysis of DbNP366-specific Id2fl/flLckCre+ and wild-type CD8+ T cells isolated from the spleen of PR8-primed/HKx31-infected mixed bone marrow chimeric mice. Data show the mean fold difference of genes from 3 biologically independent analyses. (D) Quantitative analysis by real-time PCR of Il10 mRNA from wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ DbNP366-specific (KLRG1−) CD8+ T cells from PR8-primed/HKx31-infected mixed bone marrow chimeras (day 9) and naïve CD44−CD62L+ CD8+ splenic T cells. Data show the mean Il10 expression ± SEM relative to Hprt from 3 independent samples. (E-F) Intracellular expression (E) and frequency (F) of IL-10 in IFN-γ+Id2fl/flLckCre+ (Ly5.2+) or wild-type (Ly5.1+) CD8+ T cells isolated from the spleen and the lung of PR8-primed mixed bone marrow chimeras 9 days after infection with HKx31. Data show the mean ± SEM (spleen, n = 11; lung, n = 9 mice per genotype pooled from 3 independent experiments). (D,F) Statistically significant differences were determined using a 2-tailed paired Student t test; ***P < .001. (G-H) IL-10-GFP expression (G) and frequency (H) in Id2fl/flLckCre+ (Ly5.2+) or wild-type (Ly5.1+) CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from the bronchoalveolar lavage from mixed bone marrow chimeras 9 days after infection with HKx31. (H) Data show the mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice per genotype pooled from 2 independent experiments). Statistically significant differences were determined using a Mann-Whitney U test; **P < .01. WT, wild-type.

To begin to understand why loss of Id2 in T cells protected against the weight loss associated with influenza viral infection, we reexamined our microarray data in which we compared influenza-specific wild-type and Id2-deficient CD8+ T cells isolated from mixed bone marrow chimeras 9 days after HKx31 infection for alterations in immunomodulatory cytokine expression.17 Two cytokines, IL-2 and IL-10, were strongly upregulated in the absence of Id2 (Figure 1C). Because IL-10 has previously been reported to be associated with enhanced protection through control of lung inflammation during influenza infection,4 we focused on delineating how Id2 regulates IL-10 expression in CD8+ T cells to exert its protective role.

The enhanced IL-10 expression in Id2-deficient vs wild-type influenza-specific CD8+ T cells was confirmed using quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 1D) and intracellular cytokine staining following NP366 peptide restimulation in vitro (Figure 1E-F). We then investigated whether the aberrant overexpression of IL-10 was restricted to CD8+ T cells or whether a similar mechanism was at play in CD4+ T cells. To this end, we infected bone marrow chimeras reconstituted with a mix of wild-type (Ly5.1) bone marrow and either an Il10gfp/+ (Ly5.2+) bone marrow or an Id2fl/flLckCre+Il10gfp/+ bone marrow. Consistent with our previous results, the frequency of IL-10–expressing cells measured by green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression was significantly increased in Id2-deficient CD8+ T cells isolated from the bronchoalveolar fluid (Figure 1G-H) and the lung parenchyma (data not shown) of influenza-virus–infected mice. Interestingly, Id2 deficiency also significantly increased the frequency of IL-10-GFP expression in CD4+ T cells, albeit to a lesser extent compared with CD8+ T cells (Figure 1G-H). Taken together, these data show that Id2 represses IL-10 expression in effector CD8+ and CD4+ T cells.

Id2-deficient T cells fail to induce severe GVHD

Given the important role of IL-10 in controlling inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, we hypothesized that the derepression of IL-10 in Id2-deficient T cells would protect against immune-mediated disease in an inflammatory setting such as GVHD. To test this proposal, T-cell–depleted bone marrow (C57BL/6; H2b MHC restricted) was mixed with either allogeneic wild-type (C57BL/6, Id2+/+) or Id2-deficient (C57BL/6, Id2fl/flLckCre+) T cells and cotransferred into lethally irradiated BALB/c mice (H-2d MHC restricted). In this setting, about 80% of the mice that received wild-type T cells succumbed to acute weight loss within 7 days (Figure 2A), and the mice that survived this early phase of weight loss subsequently succumbed to colitis at 4 to 5 weeks after induction of GVHD (Figure 2A-B). In contrast, mice that received Id2-deficient T cells had a significant survival advantage (Figure 2A) and showed reduced GVHD-associated immunopathology such as colitis when compared with mice that received wild-type T cells (Figure 2B).

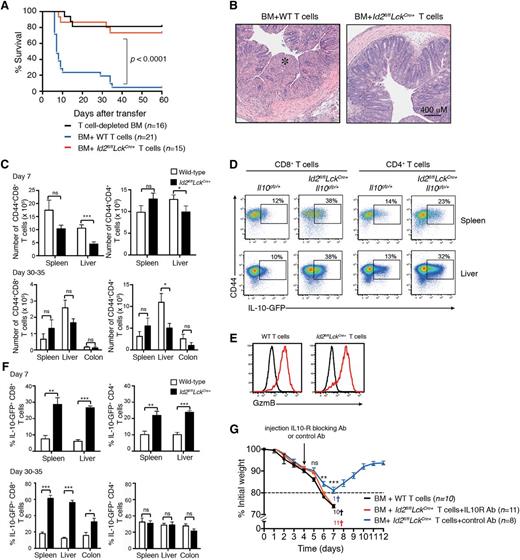

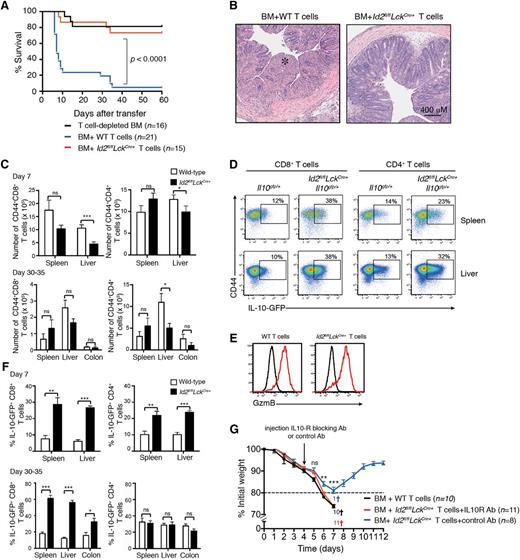

Id2-deficient T cells do not induce GVHD. T-cell–depleted bone marrow from B6 or Ly5.1+ mice was mixed with 0.5 to 1 × 106 wild-type (B6 or Il10gfp/+) or Id2-deficient (Id2fl/flLckCre+ or Id2fl/flLckCre+Il10gfp/+) T cells and then transferred into irradiated BALB/c mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of recipient mice. Data are pooled from 3 or 4 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences of survival were determined using a log-rank test. (B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of the colon 4 weeks after mice had received T cells (*, intestinal necrosis). Representative images from 2 independent experiments. (C) Number of Ly5.2+/+CD44+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, liver, and colon 7 days or 30 to 35 days after T-cell transfer (day 7, data pooled from 4 experiments; n = 10-11 mice per genotype; 30 to 35 days, data pooled from 2 experiments, n = 5-6 mice per genotype). Statistically significant differences were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test; * P < .05; ns, not significant. (D) Flow cytometric analyses of IL-10-GFP expression in Ly5.2+CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from spleen and liver of BALB/c mice 7 days after adoptive transfer of Ly5.2+Il10gfp/+ or Id2fl/flLckCre+Il10gfp/+ T cells. (E) Intracellular granzyme B expression in wild-type and Id2fl/flLckCre+ CD8+ T cells 7 days after T-cell adoptive transfer (red line, Ly5.2+CD8+ T cells; black line, Ly5.1+ bone marrow–derived donor cells). (F) Frequency of IL-10-GFP+ cells of Ly5.2+ CD44+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, liver, and colon 7 or 30 to 35 days after T-cell transfer (n = 5-6 mice per genotype pooled from 2 separate experiments). Statistical differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; *P < .05; **P < .01; *** P < .001; ns, not significant. (G) Weight loss curves in lethally irradiated BALB/c mice reconstituted with Ly5.1+/+ bone marrow cotransferred with wild-type or Id2-deficient T cells as in panel A. IL-10R blocking antibody or control antibody was injected intraperitoneally 4 days after T-cell transfer. Mice sacrificed due to severe weight loss (>20%) or clinical symptoms are indicated by a cross. Statistical differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; **P < .01; *** P < .001; ns, not significant. Ab, antibody; BM, bone marrow; GzmB, granzyme B; WT, wild-type.

Id2-deficient T cells do not induce GVHD. T-cell–depleted bone marrow from B6 or Ly5.1+ mice was mixed with 0.5 to 1 × 106 wild-type (B6 or Il10gfp/+) or Id2-deficient (Id2fl/flLckCre+ or Id2fl/flLckCre+Il10gfp/+) T cells and then transferred into irradiated BALB/c mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of recipient mice. Data are pooled from 3 or 4 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences of survival were determined using a log-rank test. (B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of the colon 4 weeks after mice had received T cells (*, intestinal necrosis). Representative images from 2 independent experiments. (C) Number of Ly5.2+/+CD44+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, liver, and colon 7 days or 30 to 35 days after T-cell transfer (day 7, data pooled from 4 experiments; n = 10-11 mice per genotype; 30 to 35 days, data pooled from 2 experiments, n = 5-6 mice per genotype). Statistically significant differences were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test; * P < .05; ns, not significant. (D) Flow cytometric analyses of IL-10-GFP expression in Ly5.2+CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from spleen and liver of BALB/c mice 7 days after adoptive transfer of Ly5.2+Il10gfp/+ or Id2fl/flLckCre+Il10gfp/+ T cells. (E) Intracellular granzyme B expression in wild-type and Id2fl/flLckCre+ CD8+ T cells 7 days after T-cell adoptive transfer (red line, Ly5.2+CD8+ T cells; black line, Ly5.1+ bone marrow–derived donor cells). (F) Frequency of IL-10-GFP+ cells of Ly5.2+ CD44+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, liver, and colon 7 or 30 to 35 days after T-cell transfer (n = 5-6 mice per genotype pooled from 2 separate experiments). Statistical differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; *P < .05; **P < .01; *** P < .001; ns, not significant. (G) Weight loss curves in lethally irradiated BALB/c mice reconstituted with Ly5.1+/+ bone marrow cotransferred with wild-type or Id2-deficient T cells as in panel A. IL-10R blocking antibody or control antibody was injected intraperitoneally 4 days after T-cell transfer. Mice sacrificed due to severe weight loss (>20%) or clinical symptoms are indicated by a cross. Statistical differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; **P < .01; *** P < .001; ns, not significant. Ab, antibody; BM, bone marrow; GzmB, granzyme B; WT, wild-type.

During the early phase of GVHD, both wild-type and Id2-deficient T cells showed a similar pattern of accumulation in the spleen, whereas Id2-deficient T cells were modestly reduced in the liver (mean total number T cells ± standard error of the mean [SEM]: wild-type, 2.3 × 106 ± 2.1 × 105 ; Id2fl/flLckCre+, 1.4 × 106 ± 2.1 × 105), consistent with the reported lower migration of Id2-deficient T cells into nonlymphoid tissues (Figure 2C).16,17 By contrast, in the late phase of the disease, wild-type and Id2-deficient T cells accumulated in a similar manner in both the colon and in the liver (Figure 2C). They showed an effector phenotype with high expression of CD44 (Figure 2D) and low expression of CD62L (data not shown). Surprisingly, and in contrast to our observations in the influenza infection,17 Id2-deficient CD8+ T cells expressed a similar amount of the cytolytic molecule granzyme B compared with wild-type T cells (Figure 2E), suggesting that a high inflammatory microenvironment and/or continuous antigenic stimulation may compensate for some of the defects associated with the loss of Id2. Seven days after induction of GVHD, the frequency of both Id2-deficient CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells expressing IL-10-GFP was significantly increased, whereas at 4 to 5 weeks, this effect was observed only in CD8+ T cells (Figure 2D, F). These data suggest that Id2 represses IL-10 in T cells and this effect is most pronounced in CD8+ T cells, perhaps reflecting the increased sensitivity of CD8+ T cells to low-level antigen expression.

To determine whether the protection against the GVHD-associated immunopathology afforded by Id2-deficient T cells was due to enhanced IL-10 production, mice that received Id2-deficient T cells were injected with an IL-10R blocking antibody (clone 1B1-3A) or a control antibody 4 days after induction of the disease and the loss of weight was monitored daily. Strikingly, the mice that received the IL-10R blocking antibody exhibited significantly more weight loss than those treated with the control antibody. This weight loss was similar to that found in mice that received wild-type T cells (Figure 2G). Overall, our data show that Id2 deficiency in T cells protects against acute GVHD immunopathology due to the enhanced production of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10.

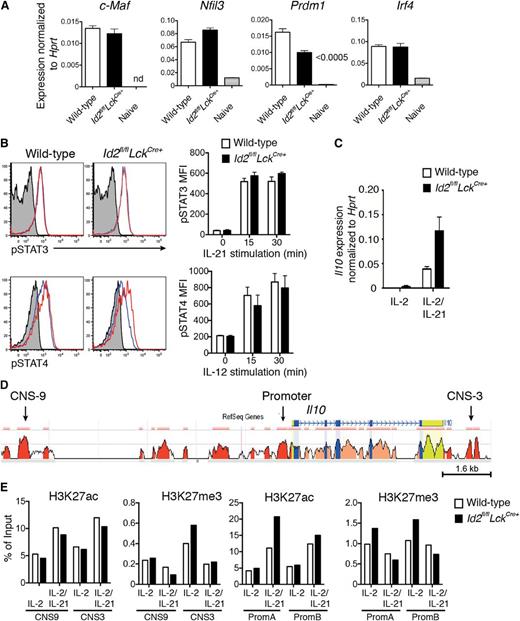

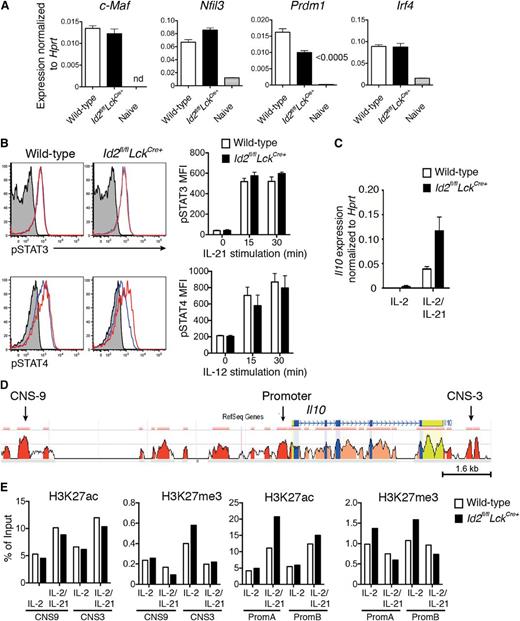

Id2 deficiency does not perturb the expression of known Il10 transcriptional regulators or the epigenetic landscape of the Il10 locus

Next, we investigated how the loss of Id2 promoted enhanced secretion of IL-10. Firstly, we analyzed the expression of key transcription factors implicated in Il10 regulation, namely Irf4, Nfil3 (encoding E4BP4), Prdm1 (encoding Blimp-1), and c-Maf, in influenza-specific CD8+ T cells.9,11,13,14 Surprisingly, loss of Id2 did not result in an increase in the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of these transcriptional activators (Figure 3A). Because the transcription factors STAT3 and STAT4 have also been shown to promote IL-10 production in T cells,27-29 we investigated whether cytokine-driven T-cell activation through IL-12 or IL-21 would increase their phosphorylation in the absence of Id2. Following stimulation, both the kinetics of induction and the magnitude of pSTAT3 and pSTAT4 expression were similar in the presence or absence of Id2, showing that these STAT signaling pathways are not altered by Id2 deficiency and were thus unlikely to account for the increase in IL-10 expression (Figure 3B). Thus, given that the known signaling candidates did not appear to be involved in enhanced IL-10 production in the absence of Id2, we asked whether the loss of Id2 affected the epigenetic status of the Il10 locus. To test this possibility, we used ChIP PCR to analyze the prevalence of activating (H3K27ac) and a repressive (H3K27me3) histone marks in the promoter and CNSs of Il10 in CD8+ T cells cultured in conditions in which Il10 is (IL-2 plus IL-21) or is not (IL-2 alone, 4 days after activation) induced (Figure 3C-E). In conditions that did not induce Il10, the prevalence of both activating and repressive histone marks were similar in wild-type and Id2-deficient CD8+ T cells. Further, the occupancy of H3K27ac at promoter and CNS regions was increased comparably in both wild-type and Id2-deficient T cells cultured in IL-21 (Figure 3D, E), consistent with the increased Il10 mRNA expression in these cells (Figure 3C). Taken together, these results show that loss of Id2 does not affect the expression of transcription factors known to activate Il10 expression or alter the epigenetic status of the Il10 locus.

Id2 deficiency does not alter the expression of key IL-10 transcriptional activators or the epigenetic status of the Il10 locus. (A) Quantitative analysis of mRNA expression by real-time PCR within wild-type DbNP366+ (KLRG1−) or Id2fl/flLckCre+ CD8+ T cells from PR8-primed HKx31-infected mice (day 9) and naïve splenic CD44−CD62L+CD8+ T cells. Data show the mean ± SEM of gene expression relative to Hprt from 3 independent samples. (B) In vitro activation of wild-type and Id2fl/flLckCre+ CD8+ T cells (day 2 cultures) with IL-21 (50 ng/mL) or IL-12 (5 ng/mL) prior to intracellular staining for pSTAT3 and pSTAT4. Histograms show representative staining after 15 min (solid blue line) or 30 min (solid red line; unstimulated cells, gray shading). Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM of pSTAT3 or pSTAT4 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) pooled from 3 independent experiments. (C) Quantitative analysis of Il10 mRNA expression by real-time PCR within in vitro–activated wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ OT-I CD8+ T cells cultured 4 days in presence of IL-2 alone or IL-2 and IL-21. Data show the mean ± SEM of gene expression relative to Hprt from 3 independent samples. (D) CNSs in the Il10 loci of mouse and human are shown. The mouse genomic sequence is used as the base sequence on the x-axis. Red represents intergenic regions with a minimal length of 100 bp and at least 70% of conservation between human and mouse as shown in the ECR Browser. The CNS-9 and CNS-3 regions are indicated. (E) ChIP analysis of the Il10 locus from in vitro–activated wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ OT-I CD8+ T cells cultured as in (C) with antiserum specific for acetylation of histone H3 at Lys27 (H3K27ac) or trimethylation of histone H3 at Lys27 (H3K27me3). Data show 1 of 2 independent experiments with similar results.

Id2 deficiency does not alter the expression of key IL-10 transcriptional activators or the epigenetic status of the Il10 locus. (A) Quantitative analysis of mRNA expression by real-time PCR within wild-type DbNP366+ (KLRG1−) or Id2fl/flLckCre+ CD8+ T cells from PR8-primed HKx31-infected mice (day 9) and naïve splenic CD44−CD62L+CD8+ T cells. Data show the mean ± SEM of gene expression relative to Hprt from 3 independent samples. (B) In vitro activation of wild-type and Id2fl/flLckCre+ CD8+ T cells (day 2 cultures) with IL-21 (50 ng/mL) or IL-12 (5 ng/mL) prior to intracellular staining for pSTAT3 and pSTAT4. Histograms show representative staining after 15 min (solid blue line) or 30 min (solid red line; unstimulated cells, gray shading). Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM of pSTAT3 or pSTAT4 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) pooled from 3 independent experiments. (C) Quantitative analysis of Il10 mRNA expression by real-time PCR within in vitro–activated wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ OT-I CD8+ T cells cultured 4 days in presence of IL-2 alone or IL-2 and IL-21. Data show the mean ± SEM of gene expression relative to Hprt from 3 independent samples. (D) CNSs in the Il10 loci of mouse and human are shown. The mouse genomic sequence is used as the base sequence on the x-axis. Red represents intergenic regions with a minimal length of 100 bp and at least 70% of conservation between human and mouse as shown in the ECR Browser. The CNS-9 and CNS-3 regions are indicated. (E) ChIP analysis of the Il10 locus from in vitro–activated wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ OT-I CD8+ T cells cultured as in (C) with antiserum specific for acetylation of histone H3 at Lys27 (H3K27ac) or trimethylation of histone H3 at Lys27 (H3K27me3). Data show 1 of 2 independent experiments with similar results.

E2A-mediated activation of Il10 expression in CD8+ T cells

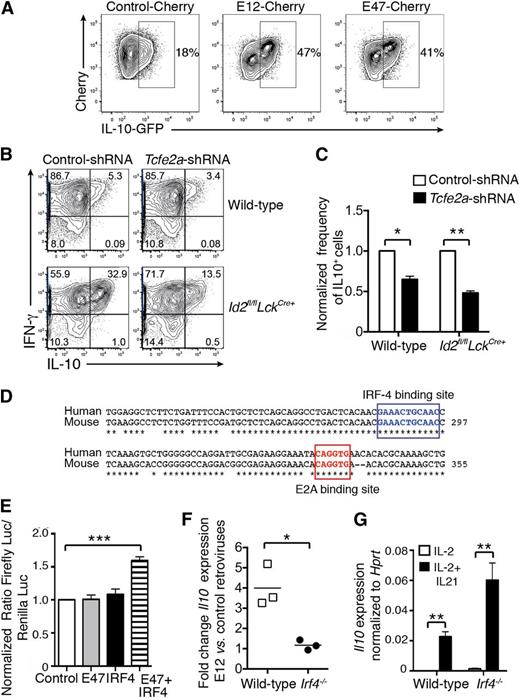

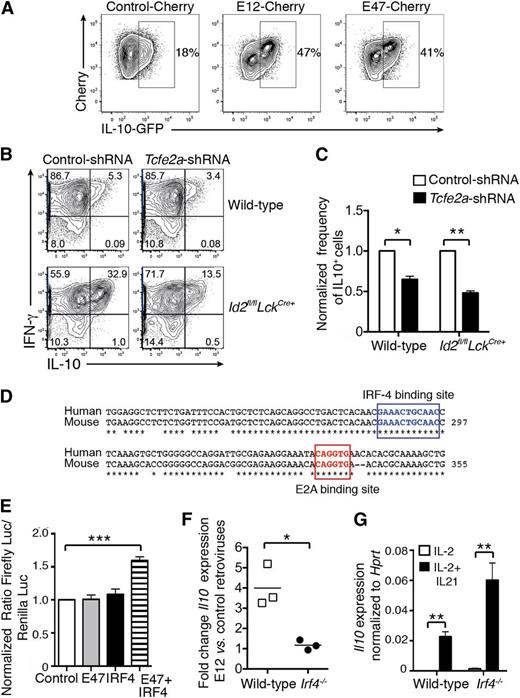

Id2 is a negative regulator of the E protein transcription factor family, and E2A is expressed in activated CD8+ T cells.30 Therefore, we hypothesized that E2A positively regulates Il10 expression in CD8+ T cells. Firstly, we determined whether overexpression of E2A would lead to enhanced IL-10 production by transducing in vitro–activated Il10 reporter (Il10gfp) CD8+ T cells with retroviruses encoding the 2 isoforms of E2A, E12, and E47. In line with our hypothesis, overexpression of either isoform strongly enhanced IL-10-GFP expression (Figure 4A). Conversely, silencing of E2A by transduction of wild-type or Id2fl/flLckCre+ OT-I T cells with a retrovirus encoding an shRNA against Tcfe2a (encoding E2A) significantly reduced the induction of IL-10 expression following OVA peptide restimulation (Figure 4B-C).

E2A promotes IL-10 expression in activated CD8+ T cells. (A) Activated Il10gfp/+ CD8+ T cells were transduced with control-Cherry, E12-Cherry, or E47-Cherry retroviruses. Two days later, Cherry+ cells were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and cells were analyzed. IL-10-GFP expression was analyzed 3 days later. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B-C) Wild-type and Id2fl/flLckCre+ OT-I cells were transduced with shRNA-tcfe2a-GFP and shRNA-control-GFP retroviruses. GFP+ cells (95% positive) were restimulated for 4 to 5 hours with SIINFEKL peptide and then analyzed for intracellular IFN-γ and IL-10 expression. (C) Frequency of IL-10+ cells among OT-I CD8+ T cells transduced with Tcfe2a shRNA normalized to the frequency of IL-10+ cells among OT-I CD8+ T cells transduced with control shRNA. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences of the test group to 1 were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; *P < .05, **P < .01. (D) E2A and IRF4 binding sites within the CNS-9 are boxed; * indicates nucleotides conserved between humans and mice. (E) NIH-3T3 were transfected with firefly luciferase (Luc) reporter construct containing the CNS-9 enhancer with the Il10 minimal promoter together with empty vector, vectors encoding either IRF4 or E47, or with both vectors. Transfection efficiency was controlled by cotransfection of a plasmid constitutively expressing the Renilla luciferase. Results show the ratio of the firefly luciferase to the Renilla luciferase luminescence normalized to the ratio in cells transfected with CNS-9/minimal promoter construct alone. Data show the mean ± SEM pooled from 3 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences of the test group to 1 were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; ***P < .001. (F) Ratio of Il10 mRNA expression evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR in wild-type or Irf4−/− OT-I T cells transduced with E12-Cherry vs control-Cherry retroviruses cultured for 2 days in the presence of IL-2 plus IL-21. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. (G) Il10 mRNA expression was measured by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized to Hprt expression in wild-type or Irf4−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells activated with OVA peptide and cultured for 2 days in the presence of IL-2 or IL-2 plus IL-21. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. (F-G) Statistical differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; *P < .05, **P < .001.

E2A promotes IL-10 expression in activated CD8+ T cells. (A) Activated Il10gfp/+ CD8+ T cells were transduced with control-Cherry, E12-Cherry, or E47-Cherry retroviruses. Two days later, Cherry+ cells were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and cells were analyzed. IL-10-GFP expression was analyzed 3 days later. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B-C) Wild-type and Id2fl/flLckCre+ OT-I cells were transduced with shRNA-tcfe2a-GFP and shRNA-control-GFP retroviruses. GFP+ cells (95% positive) were restimulated for 4 to 5 hours with SIINFEKL peptide and then analyzed for intracellular IFN-γ and IL-10 expression. (C) Frequency of IL-10+ cells among OT-I CD8+ T cells transduced with Tcfe2a shRNA normalized to the frequency of IL-10+ cells among OT-I CD8+ T cells transduced with control shRNA. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences of the test group to 1 were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; *P < .05, **P < .01. (D) E2A and IRF4 binding sites within the CNS-9 are boxed; * indicates nucleotides conserved between humans and mice. (E) NIH-3T3 were transfected with firefly luciferase (Luc) reporter construct containing the CNS-9 enhancer with the Il10 minimal promoter together with empty vector, vectors encoding either IRF4 or E47, or with both vectors. Transfection efficiency was controlled by cotransfection of a plasmid constitutively expressing the Renilla luciferase. Results show the ratio of the firefly luciferase to the Renilla luciferase luminescence normalized to the ratio in cells transfected with CNS-9/minimal promoter construct alone. Data show the mean ± SEM pooled from 3 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences of the test group to 1 were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; ***P < .001. (F) Ratio of Il10 mRNA expression evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR in wild-type or Irf4−/− OT-I T cells transduced with E12-Cherry vs control-Cherry retroviruses cultured for 2 days in the presence of IL-2 plus IL-21. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. (G) Il10 mRNA expression was measured by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized to Hprt expression in wild-type or Irf4−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells activated with OVA peptide and cultured for 2 days in the presence of IL-2 or IL-2 plus IL-21. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. (F-G) Statistical differences were determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test; *P < .05, **P < .001.

To determine whether E2A might directly regulate IL-10 expression, we searched for evolutionary conserved E-box binding sites (CANNTG) in the Il10 locus using the software rVista. A single E2A consensus binding site was identified in the cis-regulatory element CNS-9 (Figure 4D). This enhancer was first described as an IRF4-responsive element important for IL-10 expression in Th2 CD4+ T cells in collaboration with the AP1 and NFAT transcription factors.15 We therefore asked whether E2A was able to trans-activate a luciferase reporter construct in which the CNS-9 region has been cloned upstream of the Il10 minimal promoter. NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with the CNS-9 reporter construct with or without plasmid encoding either E47 or IRF4 alone or IRF4 and E47. E47 or IRF4 alone was not sufficient to trans-activate the CNS-9 reporter construct. However, when E47 and IRF4 were coexpressed, we observed a significant induction of the reporter luciferase (Figure 4E). To test whether E2A and IRF4 collaborate to enhance Il10 expression in effector CD8+ T cells, in vitro–activated wild-type and Irf4−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells were transduced with a control retrovirus or retroviruses encoding E12 (Figure 4F) or E47 (not shown) and stimulated with IL-21 to induce IL-10. As expected, wild-type OT-I T cells overexpressing E12 (Figure 4G) or E47 (data not shown) showed a 3- to 5-fold increase in Il10 mRNA expression compared with wild-type OT-I T cells transduced with the control retrovirus. By contrast, E2A overexpression did not enhance Il10 expression in Irf4−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells, demonstrating that IRF4 is required to induce E2A-mediated IL-10 expression in CD8+ T cells (Figure 4F). This was not due to a defect in Il10 induction in IRF4-deficient cells, because Il10 expression was similarly increased by IL-21 in both wild-type and Irf4−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells compared with IL-2 stimulation alone (Figure 4G). Collectively, our data show that E2A cooperates with IRF4 through an Id2-regulated pathway to promote IL-10 expression in CD8+ T cells.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that Id2 acts to inhibit E2A-mediated induction of IL-10 expression in effector CD8+ and, to a lesser extent, effector CD4+ T cells. This affords protection against the development of T-cell–driven GVHD disease and ameliorates severe disease associated with influenza virus infection. Blockade of IL-10R signaling in mice that received Id2-deficient T cells mirrored the pathology observed in mice that received wild-type T cells. Thus, IL-10 produced by Id2-deficient T cells was responsible for the protection against GVHD immunopathology. Because genetic polymorphisms that determine the expression of human IL-10 have clear impacts on disease outcome and transplant-related mortality,2 our findings suggest that targeting the fate decisions of transplanted T cells may be critical for the therapeutic success of bone marrow transplantation.

IL-10 has also been shown to be immunostimulatory when delivered at high doses.31-34 In this setting, CD8+ T cells showed enhanced cytotoxicity, which has been proposed as a key reason for the failure of IL-10 in the treatment of inflammatory diseases,34 although we did not observe any alteration of the cytotoxic effector molecules interferon-γ (IFN-γ) or granzyme B when IL-10R signaling was blocked (F.M. and G.T.B, unpublished data). Overall, increased IL-10 induced by Id2 loss was not sufficient to drive an adverse outcome and highlights the importance of understanding how IL-10 is regulated in T cells in vivo.

We show that the rewiring of T cells is determined by Id2, a key regulator of the timing of IL-10 expression required to balance the protective effects of the immune response with the need to limit inflammation following challenges such as viral infection and GVHD. In these T cells, E2A can collaborate with IRF4 to trans-activate a reporter construct containing the CNS-9 enhancer and the Il10 minimal promoter, a mechanism similar to the corequirement for IRF4 and NFAT for IL-10 production in Th2 cells15 and B cells, where IRF4 and E2A synergistically activate the Ciita promoter and the Igk locus.35,36 In line with these results, Irf4 deficiency abrogates the enhanced IL-10 expression induced by enforced expression of E2A.

In influenza lung infection, CD4+ T-cell–derived IL-2 acts synergistically with innate immune-cell–derived IL-27 to amplify IL-10 expression by virus-specific CD8+ T cells through a Blimp-1–dependent mechanism.14 T-cell–derived IL-10 has also been shown to control excess inflammation through an autocrine feedback loop via the IL-10R on effector T cells,37 and IL-10 can act to influence memory CD8+ T-cell differentiation through the induction of STAT3 phosphorylation.38 Previously, we have shown that ablation of Id2 in CD8+ T cells resulted in enhanced E2A transcriptional activity. This prevented CD8+ T-cell differentiation into short-lived effector cells skewing cell fate toward memory T-cell formation,17 but the impact of Id2 deficiency on the functions of the cells was less apparent. The failure of short-lived effector T cells to differentiate in the absence of Id2 does not appear to be a consequence of the overproduction of IL-10, because the blockade of IL-10R signaling in vivo did not rescue the population of short-lived effector cells in Id2-deficient CD8+ T cells.

Although the pathways described above provide an explanation for the induction of IL-10 during inflammation, they do not shed light on how IL-10 is initially limited to drive a strong early immune response for optimal induction of immune protection. The level of Id2 expressed by T cells during an immune response parallels the degree of inflammation that occurs, and Id2 directly inhibits E2A expression in a dose-specific manner.17,18 Interestingly, Id2 expression is upregulated following T-cell activation,17 as is E2A expression.30 This suggests a model in which the upregulation of Id2 expression acts to prevent the E2A-dependent increase of IL-10 early during immune activation. Thus, Id2 drives a key molecular pathway by which IL-10 production can be titrated in a dose-specific manner to balance pro- and anti-inflammatory arms of the immune response required for protective immunity.

In summary, we show that modification of the transcriptional wiring of T cells through the inhibition of Id2 to generate IL-10–expressing T cells enables long-term engraftment of transplanted bone marrow while minimizing immune pathology. Targeting such regulators could be beneficial in the treatment of T-cell–mediated inflammatory disease.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank T. W. Mak (Campbell Family Cancer Research Institute) for the Irf4−/− mice; R.A. Flavell (Yale University) for the IL10gfp mice; S. H. Im for providing the CNS-9/IL-10 reporter construct; R. Cole, A. Pomphrey, and J. Vella for maintaining and caring for the mice; and M. Camilleri and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute flow cytometry core facility for technical assistance.

J.R.G. was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) training fellowship, and G.T.B. and S.N. were supported by Australian Research Council future fellowships. R.W.J. is a principal research fellow of the NHMRC and supported by NHMRC program and project grants, The Leukemia Foundation of Australia, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. This work was supported by a project grant (APP1042582) from the NHMRC and Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support and Australian Government NHMRC IRIIS.

Authorship

Contribution: F.M., M.G., J.R.G., C.S., and G.T.B. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and generated figures; A.K. participated in discussions; R.W.J. analyzed data; and F.M., S.L.N., and G.T.B. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gabrielle T. Belz, Division of Molecular Immunology, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; e-mail: belz@wehi.edu.au.