Abstract

Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been a remarkable success for the treatment of Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). However, a significant proportion of patients treated with TKIs develop resistance because of leukemia stem cells (LSCs) and T315I mutant Bcr-Abl. Here we describe the unknown activity of the natural product berbamine that efficiently eradicates LSCs and T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clones. Unexpectedly, we identify CaMKII γ as a specific and critical target of berbamine for its antileukemia activity. Berbamine specifically binds to the ATP-binding pocket of CaMKII γ, inhibits its phosphorylation and triggers apoptosis of leukemia cells. More importantly, CaMKII γ is highly activated in LSCs but not in normal hematopoietic stem cells and coactivates LSC-related β-catenin and Stat3 signaling networks. The identification of CaMKII γ as a specific target of berbamine and as a critical molecular switch regulating multiple LSC-related signaling pathways can explain the unique antileukemia activity of berbamine. These findings also suggest that berbamine may be the first ATP-competitive inhibitor of CaMKII γ, and potentially, can serve as a new type of molecular targeted agent through inhibition of the CaMKII γ activity for treatment of leukemia.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), which accounts for approximately 20% of all adult leukemias,1 is characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph+), which results from a chromosomal translocation between the Bcr gene on chromosome 22 and the Abl gene on chromosome 9.2 This translocation produces the fusion protein Bcr-Abl that has constitutive kinase activity3 and is essential for the growth of CML cells and has become an attractive target for treatment of Ph+ CML cases, and the Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are now first-line therapeutic agents.4-6 Inhibition of Bcr-Abl with Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as imatinib (IM), is highly effective in controlling CML at chronic phase but not curing the disease. This is largely because of the inability of these kinase inhibitors to kill leukemia stem cells (LSCs) responsible for initiation, drug resistance, and relapse of CML4-6 and Bcr-Abl gene mutation, particularly T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clones.7-9 Thus, drug resistance associated with TKIs has created a need for more potent and safer therapies against other targets apart from the Bcr-Abl oncogenic kinase.

Increasing evidence shows that traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) products not only play important roles in the discovery and development of drugs, but can also be used as molecular probes for identifying therapeutic targets. Homoharringtonine, arsenic trioxide, and triptolide are 3 famous examples.9-11 Berbamine (BBM) is a structurally unique bisbenzylisoquinoline isolated from TCM Berberis amurensis, and has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for treating a variety of diseases from inflammation to tumors for many years.12,13 It possesses a unique profile of biologic activities. Berbamine and its derivatives have been shown potent anti-inflammatory14,15 and antitumor activities.16 We previously demonstrated that berbamine and its derivatives potently inhibited the growth of imatinib (IM)–resistant CML cells but not normal hematopoietic cells.17,18

Extensive scrutiny of its molecular targets and mechanism of action in the past few decades has provided important insights. At the cellular level, berbamine exhibits significantly antiproliferative activities of a variety of leukemia,17-21 lymphoma,22 multiple myeloma,23 and solid tumor cell lines.24-27 At the molecular level, berbamine-mediated antitumor activity was shown to be involved in PI3K/Akt,22 nuclear factor kappaB,23 Fas-mediated apoptosis,26 calmodulin,28,29 phospholipase A2,16,30,31 P-glycoprotein,24 and telomerase activity.32 A previous study showed that compound E6, an analog of berbamine, can inhibit calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) activity through affecting calmodulin (CaM) but not MLCK.33 Thus, the molecular target of berbamine has not been identified and its molecular mechanism also remains largely elusive to date.

In this study, we first evaluated whether berbamine affected LSC and T315I mutant–Bcr-Abl cell clones of CML and then used berbamine as a molecule probe to identify molecular targets of berbamine for its antileukemia activity. We systematically evaluated the effects of berbamine on the candidate targets through compound structure-activity relationship (SAR) in vitro and in vivo, and computer docking modeling. Both in vitro and in vivo studies revealed that berbamine can override TKI-resistance to LSC and T315I mutant–Bcr-Abl and that Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II γ (CaMKII γ) was a specific and critical target of berbamine for its antileukemia activity. Moreover, we found that CaMKII γ was a critical molecular switch for regulating NF-κB, Wnt/β-catenin, and Stat3 pathways. In particular, CaMKII γ was highly activated in CML LSCs, but not in normal blood cells. Thus, targeting CaMKII γ offers a unified molecular mechanism of the natural product berbamine that can efficiently eradicate LSC and T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clones. We also revealed a previously unknown activity of berbamine: targeting the ATP-binding pocket of CaMKII γ, which has important implications in the application of berbamine analogs for treatment of CML.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Phospho-CaMKII γ (Thr287) and CaMKII γ rabbit antibodies were prepared in our laboratory and the antibody dilutions for Western blotting are 1:2000 and 1:1000, respectively. NF-κBp65, laminm, PARP, caspase-3, caspase-9, IKKα, IkBα, GAPDF, and β-actin antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; β-catenin, phosphor-PKC, PKC antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Phosphor-Stat3 (Tyr705) mouse mAb and β-catenin rabbit antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Stat3 mouse mAb was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. L-C3II antibody and purified recombinant CaMKII γ protein were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Ethics statement

Normal blood cells and primary leukemia cell samples were isolated from healthy volunteers or leukemia patients with their written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All experiments were approved by the ethics committee of Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University.

Computer docking

A model of the CaMKII γ in complex with calmodulin was built using Modeller based on the x-ray crystal of CaMK2δ/calmodulin complex.

Cell culture

Two pairs of human CML cell lines were used: K562 and IM-resistant K562 containing 2.5% CD34+ cells, and KCL-22 and IM-resistant KCL-22M with T315I mutant Bcr-Abl. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C in a 95% air, 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Kinase assay

CaMKIIγ kinase activity assays were performed as previously described.34

TKI-resistant K562 cells and primary CML xenograft models and treatment

All animal procedures were approved by the institution's ethics committee. To establish xenograft model, female nude mice (6-weeks) were injected subcutaneously in the left or right flank with 2 × 107 TKI-resistant K562 cells in a 0.2-mL suspension. To establish primary CML xenograft model, female nude (6-weeks) were injected subcutaneously in the left or right flank using primary CML cells from a CML patient at blast crisis. BBM or imatinib or vehicle was administered at 100 mg/kg body weight orally 3 times daily for 10 consecutive days. Tumor and mouse weights were measured at the end of experiments.

Western blotting analysis

Cell specimens were washed twice with PBS buffer and total cellular protein was extracted using radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA). Cell extracts were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (NC; Whatman) and blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBS-Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then reacted with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing 3 times with PBS-T, membranes were probed with a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature, and reacted with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SD. Differences were evaluated by t test analysis of variance and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Berbamine overrides TKI-resistance to LSCs and T315I mutant-Bcr-Abl of CML

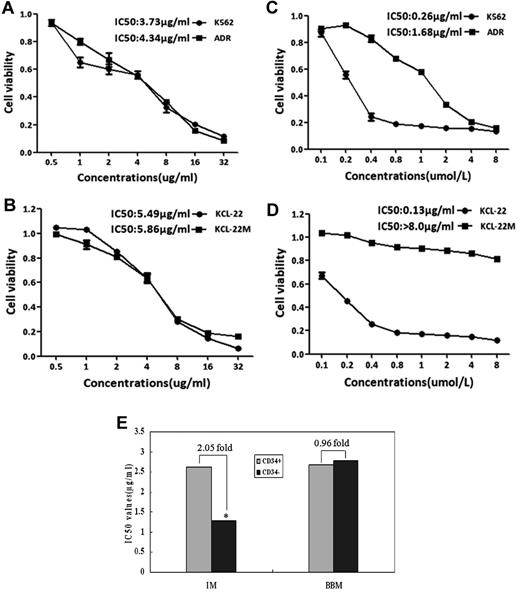

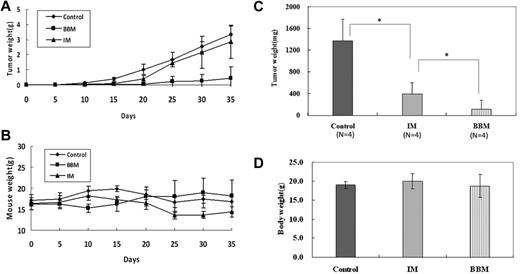

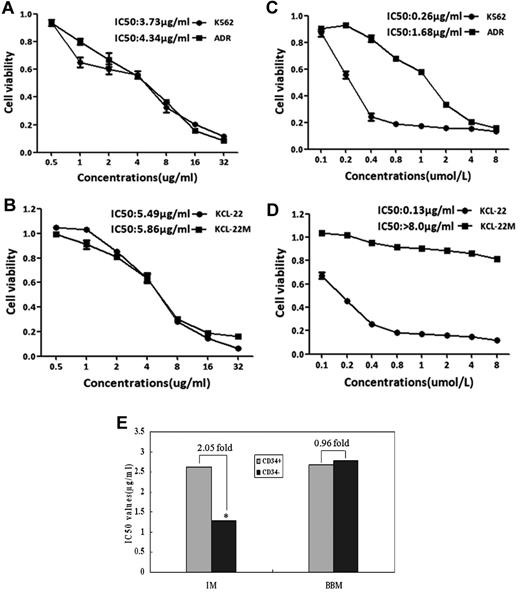

Because the TKI-resistance in Ph+ leukemia is mainly because of the insensitivity of LSCs to these TKIs and the selection of cells expressing TKI resistant Bcr-Abl mutants, especially T315I mutant-Bcr/Abl, Corbin and Hamilton reported that the inhibition of Bcr-Abl kinase activity alone is insufficient to eradicate LSCs, and that an unknown Bcr-Abl kinase activity-independent pathway in CML plays a crucial role in the maintenance of these cells.35,36 Our previous studies showed that the natural product berbamine analogs exhibit antiproliferative effects on IM-resistant CML cells,17,18 but it is unknown whether these compounds affect LSCs and T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clones of CML. Therefore, we used 2 pairs of CML cell models: IM-resistant K562 cells containing CD34+ cells and IM-resistant KCL-22M cells harboring T315I mutants of Bcr-Abl, to determine whether berbamine affected LSCs and T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clones. Leukemia cells were treated with berbamine or imatinib at various concentrations for 72 hours and cell proliferation was measured. Surprisingly, both LSCs and T315I mutants did not affect berbamine's antileukemia activity (Figure 1A-B). Unlike IM which failed to inhibit both IM-resistant K562 and KCL-22M cells (Figure 1C-D), berbamine not only significantly inhibited IM-resistant K562 and KCL-22M cells but also IM-sensitive-K562 and KCL-22 cells (Figure 1A-B). To confirm these observations, primary CML CD34+ stem cells and CD34− leukemia cells from CML patients at blast crisis were treated with BBM or IM at various concentrations for 72 hours and cell viability was measured. As expected, BBM also potently suppressed the growth of both CML CD34− leukemia cells and CD34+ stem cells, the IC50 values were 2.78 μg/mL and 2.68 μg/mL, respectively (Figure 1E). In contrast, IM preferentially inhibited the growth of CD34− leukemia cells compared with CD34+ stem cells, and the IC50 values for CD34− leukemia cells and CD34+ stem cells were 1.28 μg/mL and 2.62 μg/mL, respectively (Figure 1E). To validate whether BBM could eradicate IM-resistant K562 leukemia xenografts in vivo, nude mice bearing IM-resistant K562 xenografts were dosed with BBM. As shown in Figure 2A, berbamine induced pronounced regression of IM-resistant K562 leukemia xenografts without obvious body weight loss (Figure 2B). In addition, berbamine also significantly inhibited the growth of primary CML cells in immunocompromised mice. Tumor weights in control, IM and BBM-treated groups were 1372.75 ± 402.0 mg, 398.5 ± 208.08 mg, and 111.25 ± 169.0 mg, respectively (Figure 2C), and the body weights of tumor-bearing mice were 18.95 ± 0.84 g, 19.97 ± 1.97 g, and 18.77 ± 3.04 g, respectively at the end of experiment (day 15; Figure 2D).

Berbamine overrides TKI-resistance to leukemia stem cells and T315I mutant–Bcr-Abl of CML. (A-D) Effect of berbamine (A-B) and IM (C-D) on the growth of IM-resistant K562 cells containing LSCs and IM-resistant T315I mutant Bcr-Abl cells (KCL-22M). Two pairs of CML cell lines: K562 cell and IM-resistant K562 cells (containing 2.5% LSCs), KCL-22 and IM-resistant KCL-22M (T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clone) were treated with berbamine or IM at various concentrations for 72 hours and cell viability were measured using MTT assay. IM-sensitive K562 and KCL-22 cells were used as controls. (E) Effect of BBM and IM on the growth of CD34+ and CD34− leukemia cells. CML CD34+ stem cells and CD34− leukemia cells were treated with BBM or IM at various concentrations. After 72 hours in culture, cell viability was measured using MTT assay and IC50 values were calculated. IM was used as control (*P < .01).

Berbamine overrides TKI-resistance to leukemia stem cells and T315I mutant–Bcr-Abl of CML. (A-D) Effect of berbamine (A-B) and IM (C-D) on the growth of IM-resistant K562 cells containing LSCs and IM-resistant T315I mutant Bcr-Abl cells (KCL-22M). Two pairs of CML cell lines: K562 cell and IM-resistant K562 cells (containing 2.5% LSCs), KCL-22 and IM-resistant KCL-22M (T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clone) were treated with berbamine or IM at various concentrations for 72 hours and cell viability were measured using MTT assay. IM-sensitive K562 and KCL-22 cells were used as controls. (E) Effect of BBM and IM on the growth of CD34+ and CD34− leukemia cells. CML CD34+ stem cells and CD34− leukemia cells were treated with BBM or IM at various concentrations. After 72 hours in culture, cell viability was measured using MTT assay and IC50 values were calculated. IM was used as control (*P < .01).

Berbamine inhibits the growth of TKI-resistant CML cells and primary CML cells in immunocompromised mice. BBM or imatinib was administered at 100 mg/kg body weight orally 3 times daily for 10 consecutive days, 24 hours after the subcutaneous injection of 2 × 107 TKI-resistant K562 cells or primary CML cells. (A) Effects of BBM and IM on the growth of TKI-resistant tumors. (B) Effects of BBM and IM on body weight of tumor-bearing mice. (C) Effects of BBM and IM on the growth of primary CML cells at the end of experiment (day 15). (D) Effects of BBM and IM on body weight of tumor-bearing mice (n = 4; *P < .01).

Berbamine inhibits the growth of TKI-resistant CML cells and primary CML cells in immunocompromised mice. BBM or imatinib was administered at 100 mg/kg body weight orally 3 times daily for 10 consecutive days, 24 hours after the subcutaneous injection of 2 × 107 TKI-resistant K562 cells or primary CML cells. (A) Effects of BBM and IM on the growth of TKI-resistant tumors. (B) Effects of BBM and IM on body weight of tumor-bearing mice. (C) Effects of BBM and IM on the growth of primary CML cells at the end of experiment (day 15). (D) Effects of BBM and IM on body weight of tumor-bearing mice (n = 4; *P < .01).

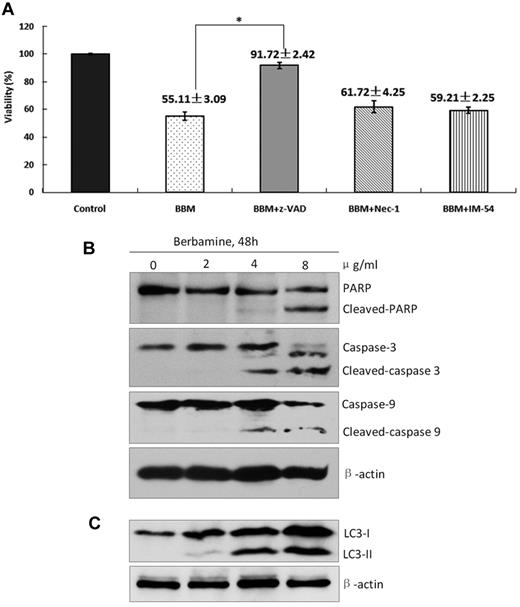

To determine which cell death pathway was induced by berbamine, IM-resistant K562 cells were treated with berbamine at 4.0 μg/mL in the presence of zVADfmk, NEC-1, and IM-54 for 48 hours and cell viability was measured using FCM. As presented in Figure 3A, berbamine-treated leukemia cells had a markedly increased viability in the presence of z-VADfmk, and a slightly increased viability in the presence of NEC-1 and IM-54 (Figure 3A). Western blot results showed that PARP cleavage, as well as cleaved-caspases 3 and 9, were detected in berbamine-treated cells (Figure 3B). These results indicate that apoptosis pathway is mainly activated along with the necroptosis and necrosis in CML cells after treatment with berbamine. To assess whether autophagy is also involved in berbamine-induced cell death, we subsequently evaluated the expression level of LC-3 II of cells treated with BBM. Interestingly, we also observed a marked increase of LC3 II after BBM treatment for 48 hours (Figure 3C). These findings suggest that berbamine overrides TKI-resistance to LSCs and T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clones through inhibiting unknown Bcr-Abl kinase activity-independent pathway.

Berbamine induces apoptotic and autophagic death of leukemia cells. (A) Effect of berbamine on the viability of CML cells in the presence of various cell death inhibitors. CML cells were treated with BBM at 4 μg/mL in the presence of z-VAD (50μM), Nec-1 (25μM), or IM-54 (5μM) for 24 hours, and then collected for analysis of cell viability using FCM (*P < .01). (B-C) Berbamine treatment induced cleaved PARP, cleaved-caspase-3, cleaved-caspase-9, and LC3-II levels of CML cells in dose-dependent manners. CML cells were treated with BBM at the indicated concentrations for 48 hours, followed by Western blot analysis for PARP, caspase-3, caspase-9, and LC3-II. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Berbamine induces apoptotic and autophagic death of leukemia cells. (A) Effect of berbamine on the viability of CML cells in the presence of various cell death inhibitors. CML cells were treated with BBM at 4 μg/mL in the presence of z-VAD (50μM), Nec-1 (25μM), or IM-54 (5μM) for 24 hours, and then collected for analysis of cell viability using FCM (*P < .01). (B-C) Berbamine treatment induced cleaved PARP, cleaved-caspase-3, cleaved-caspase-9, and LC3-II levels of CML cells in dose-dependent manners. CML cells were treated with BBM at the indicated concentrations for 48 hours, followed by Western blot analysis for PARP, caspase-3, caspase-9, and LC3-II. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Berbamine binds to and inhibits CaMKII γ of CML cells

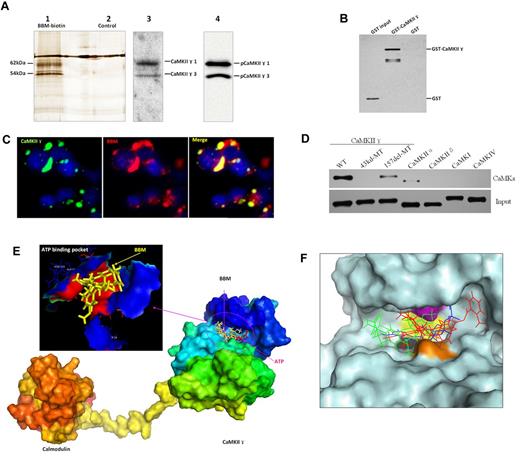

To identify molecular targets of berbamine, berbamine was chemically linked to an agarose affinity matrix and used as a molecular probe. Whole cell lysates of K562 cells were incubated with the berbamine affinity matrix. After extensively washed, the interaction proteins with berbamine on the affinity matrix were eluted using berbamine as a competitor (see supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). SDS-PAGE analysis revealed that 2 bands of approximately 62 kDa and 54 kDa were captured by berbamine (Figure 4A lane 1). These 2 bands were identified as CaMKII γ isoform 1(62 kDa) and isoform 3 (54 kDa), respectively, by mass spectrometry (MS) and confirmed by Western blot (Figure 4A lane 3). Notably, berbamine also bound to active (phosphorylated)-CaMKII γ (pCaMKII γ), suggesting that berbamine may target both nonphosphorylated CaMKII γ and active CaMKII γ (Figure 4A lane 4). To confirm whether berbamine binds directly to CaMKII γ, we performed a GST pull-down assay. Purified GST-CaMKII γ or GST protein was incubated with biotinylated berbamine and the complex was isolated with streptavidin agarose. Western blot showed that berbamine specifically pulled down CaMKII γ protein, but not GST protein (Figure 4B). To investigate whether berbamine binds to CaMKII γ protein in cells, we transiently overexpressed CaMKII γ that was fused to an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP-CaMKII γ) using 293T cells and then treated the cells with biotinylated berbamine, which was revealed by Rhodamine conjugated streptavidin (supplemental Methods). We observed that biotinylated berbamine was colocalized with EGFP-CaMKII γ in a specific manner in 293T cells (Figure 4C).

Berbamine specifically binds to the ATP-binding pocket of CaMKII γ and inhibits its kinase activity. (A) BBM physically interacts with CaMKII γ proteins. Two proteins of ∼ 62 kDa and 54 kDa were captured specifically by BBM as shown by silver staining (lane 1). These 2 bands were identified as CaMKIIγ isoform 1 (62 kDa) and isoform 3 (54 kDa), respectively, by mass spectrometry (MS) and confirmed by Western blot with total and phospho-CaMKIIγ antibodies (lanes 3-4). (B) BBM directly binds to CaMKII γ protein. Purified GST-CaMKIIγ protein was incubated with biotinylated BBM and the complex was isolated with streptavidin agarose. Western blot with anti-GST antibody revealed that BBM specifically pulled down CaMKIIγ proteins (lane 1), but not GST protein (lane 2). GST protein was used as negative control. (C) Confocal images of BBM colocalization with CaMKII γ in 293T cells. Green: EGFP-tagged CaMKIIγ protein. Red: biotin-labled BBM visualized by Rhodamine-labeled streptavidin. Yellow: BBM was predominantly colocalized with CaMKIIγ protein in 293T cells. (D) Berbamine selectively binds to ATP binding pocket of CaMKIIγ. (E) BBM molecule is located within the ATP binding pocket of CaMKIIγ protein. The model of the CaMKIIγ in complex with calmodulin was built using Modeller based on the x-ray crystal of CaMKIIδ/calmodulin complex. (F) Best docking poses of ATP (blue), XBA24 (red), and berbamine (green) at the ATP-binding pocket of CaMKIIγ. The ligand is clamped by 4 surface residues in CaMKIIγ docking groove: K43 (purple), V74 (black), F90 (yellow), and D157 (brown).

Berbamine specifically binds to the ATP-binding pocket of CaMKII γ and inhibits its kinase activity. (A) BBM physically interacts with CaMKII γ proteins. Two proteins of ∼ 62 kDa and 54 kDa were captured specifically by BBM as shown by silver staining (lane 1). These 2 bands were identified as CaMKIIγ isoform 1 (62 kDa) and isoform 3 (54 kDa), respectively, by mass spectrometry (MS) and confirmed by Western blot with total and phospho-CaMKIIγ antibodies (lanes 3-4). (B) BBM directly binds to CaMKII γ protein. Purified GST-CaMKIIγ protein was incubated with biotinylated BBM and the complex was isolated with streptavidin agarose. Western blot with anti-GST antibody revealed that BBM specifically pulled down CaMKIIγ proteins (lane 1), but not GST protein (lane 2). GST protein was used as negative control. (C) Confocal images of BBM colocalization with CaMKII γ in 293T cells. Green: EGFP-tagged CaMKIIγ protein. Red: biotin-labled BBM visualized by Rhodamine-labeled streptavidin. Yellow: BBM was predominantly colocalized with CaMKIIγ protein in 293T cells. (D) Berbamine selectively binds to ATP binding pocket of CaMKIIγ. (E) BBM molecule is located within the ATP binding pocket of CaMKIIγ protein. The model of the CaMKIIγ in complex with calmodulin was built using Modeller based on the x-ray crystal of CaMKIIδ/calmodulin complex. (F) Best docking poses of ATP (blue), XBA24 (red), and berbamine (green) at the ATP-binding pocket of CaMKIIγ. The ligand is clamped by 4 surface residues in CaMKIIγ docking groove: K43 (purple), V74 (black), F90 (yellow), and D157 (brown).

To examine whether berbamine analogs inhibit CaMKII γ activity in vitro, purified CaMKII γ was activated by Ca2+/calmodulin and treated with berbamine analogs. As expected, berbamine inhibited the activity of CaMKII γ, and its IC50 value was approximately 4.0 μg/mL. Moreover, 2-methylbenzoyl berbamine, a berbamine analog with more potent antileukemia activity, exhibited more potent inhibition activity for this kinase, and its IC50 value was approximately 0.5 μg/mL.

Berbamine selectively binds to CaMKII γ by targeting ATP binding pocket

To determine whether berbamine selectively targets to CaMKII-γ, we constructed a variety of CaMKs expression vectors, including CaMKII γ, CaMKII α, CaMKII δ, CaMKI and CaMKIV, and transfected 293T cells (supplemental Methods). Cellular proteins were extracted for coimmunoprecipitation using biotinylated berbamine. Western blot results showed that biotinylated berbamine strongly bound to CaMKII γ, and weekly bound to CaMKII α, but not to CaMKII δ, CaMKI, and CaMKIV (Figure 4D). These results indicate that berbamine selectively targets to CaMKII γ but not to other CaMKs.

To reveal the potential binding pockets of CaMKII γ for berbamine, we built a model of the CaMKII γ in complex with calmodulin. As shown in Figure 4E and F, modeling the binding of berbamine shows the potential to bind into ATP binding pocket. Figure 4F shows the best docking poses of ATP (blue), berbamine (green) and 2-methylbenzoyl berbamine (red) in the ATP-binding sites. The 3 molecules all fit the groove and are tightly clamped by the 4 residues in CaMKII γ: K43 (shown as purple), V74 (black), F90 (yellow), and D157 (brown). This is predicted to compete with ATP molecule. To verify whether berbamine is clamped by these amino acid residues, we constructed 2 mutants of CaMKII γ using site-directed mutagenesis (supplemental Methods). One is mutated Lys43 of this kinase to methionine to generate a kinase-deficient CaMKII γ mutant labeled 43kd-MT. The other is a deletion mutated Asp157 of the kinase labeled 157del-MT. We next transfected 293T cells with these mutant CaMKII γ kinases for 48 hours and then extracted total cellular proteins for coimmunoprecipitation. Western blot results showed that mutation of Lys43 (43kd-MT) abolished binding of berbamine to this kinase, and deletion of the Asp157 (157del-MT) greatly attenuated binding of berbamine to this kinase (Figure 4D). Consistent with these observations, we found that the inhibitory effect of berbamine on CaMKII γ activity was overcome by increasing the concentrations of ATP molecules (supplemental Figure 1). These results suggest that berbamine may be an ATP-competitive inhibitor of CaMKII γ.

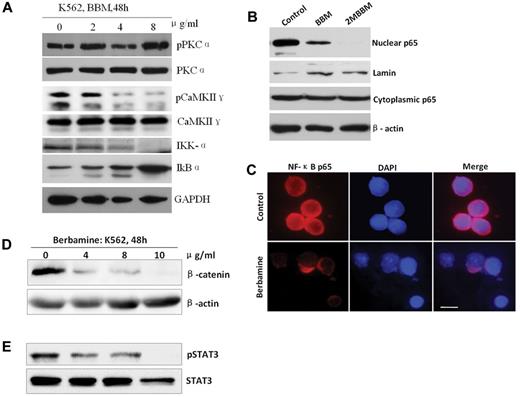

Berbamine inhibits CaMKII γ-dependent NF-κB, β-catenin, and Stat3 signaling pathways

Berbamine analogs inhibit NF-κB signaling pathways,20,22 which is constitutively activated in primitive leukemia stem/progenitor cells.37 Moreover, CaMKII γ mediates activation of NF-κB signaling pathway in leukemia cells.38 Therefore, we next examined the effects of berbamine on downstream targets of CaMKII γ. K562 cells were treated with berbamine and then collected for analyses of NF-κB signaling pathway. As shown in Figure 5A, berbamine treatment significantly down-regulated IKKα, a downstream target of CaMKII γ, with a dose-dependent manner, which in turn caused an increase of IkBα (Figure 5A). Consistent with these results, treatment of leukemia cells with berbamine and 2-methylbenzoyl berbamine (2MBBM) resulted in a significant decrease of the nuclear NF-κB p65 protein, but the cytoplasmic NF-κB p65 protein was not changed substantially (Figure 5B). Immunofluorescence staining results further confirmed that the treatment of leukemia cells with berbamine led to the blockage of NF-κB p65 into the nuclei (Figure 5C; supplemental Methods).

Berbamine inhibits CaMKII γ-dependent NF-κB, β-catenin, and Stat3 without affecting its upstream target PKCα. (A) Effect of berbamine on PKCα, CaMKIIγ, IKK-α, and IkBα. (B-C) Berbamine analogs blocked nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 realed by Western blot (B) and immunofluorescent staining (C). (C) Immunofluorescent image results exhibited a significant decrease of nuclear NF-κB p65 of leukemia cells after treatment of berbamine. Cells were immobilized on coverslips, fixed, permeabilized, and subjected to immunostaining of p65 (red fluorescence) and nuclear counterstaining (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm. (D-E) Berbamine inhibited CaMKIIγ downstream targetsβ-catenin (D) and Stat3 (E) of leukemia cells. Leukemia cells were treated with berbamine at various concentrations for 48 hours and harvested for analysis of upstream (PKCα) and downstream (IKK-α, IkBα,NF-κB p65, β-catenin and Stat3) targets of CaMKIIγ using Western blotting or immunofluorescent staining.

Berbamine inhibits CaMKII γ-dependent NF-κB, β-catenin, and Stat3 without affecting its upstream target PKCα. (A) Effect of berbamine on PKCα, CaMKIIγ, IKK-α, and IkBα. (B-C) Berbamine analogs blocked nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 realed by Western blot (B) and immunofluorescent staining (C). (C) Immunofluorescent image results exhibited a significant decrease of nuclear NF-κB p65 of leukemia cells after treatment of berbamine. Cells were immobilized on coverslips, fixed, permeabilized, and subjected to immunostaining of p65 (red fluorescence) and nuclear counterstaining (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm. (D-E) Berbamine inhibited CaMKIIγ downstream targetsβ-catenin (D) and Stat3 (E) of leukemia cells. Leukemia cells were treated with berbamine at various concentrations for 48 hours and harvested for analysis of upstream (PKCα) and downstream (IKK-α, IkBα,NF-κB p65, β-catenin and Stat3) targets of CaMKIIγ using Western blotting or immunofluorescent staining.

To determine whether berbamine had potent off-target effects that would block other signaling molecules, we tested its ability to inhibit phosphorylation of protein kinase C α (PKC α), an upstream target of CaMKII γ. At concentrations that significantly inhibited phosphorylation of CaMKII γ, berbamine had no effect on phosphorylation of PKC α (Figure 5A). These results suggest that the observed inhibition of CaMKII γ by berbamine is not the consequence of nonspecific toxicity at the cellular level, and that CaMKII γ is probably the target of berbamine for its antileukemia activity.

It is known that CaMKII γ is also a critical activator of Wnt/β-catenin and Stat3 pathways.39 Thus, we next determined whether berbamine affect β-catenin and Stat3, which are essential for survival and self-renewal of LSCs,40,41 in leukemia cells. Leukemia cells were treated with berbamine, and total cellular proteins were extracted for analysis of β-catenin and Stat3. The Western blot results showed that berbamine treatment caused a significant decrease of β-catenin protein levels with dose-dependent manners (Figure 5D). Similarly, berbamine also potently inhibited phosphorylation of Stat3 of CML cells (Figure 5E).

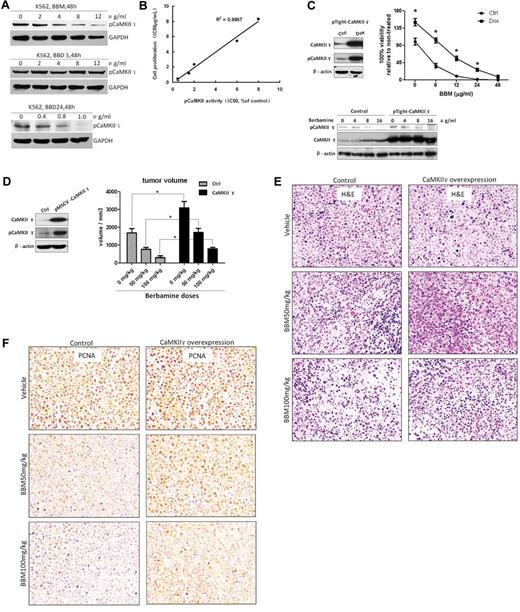

CaMKII γ is a critical target of berbamine for its antileukemia activity

To determine whether berbamine-mediated antileukemia activity is mainly caused by inhibition of CaMKII γ activity, we synthesized 54 berbamine analogs with IC50 for inhibition of cell proliferation spanning 3 orders of magnitude18 and performed structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis. O-(ethoxycabonylmethyl)berbamine) (BBD5), an inactive analog, was used as a negative control. 2-methylbenzoyl berbamine (BBD24), a potent active analog, was used as positive active compound for checking its inhibitory effect on CaMKII γ activity (Figure 6A). We selected 6 berbamine analogs with IC50 for inhibition of cell proliferation spanning 3 orders of magnitude: BBM and analogs BBD3, BBD12, BBD15, BBD24, and CP15 for their antiproliferative effect on leukemia cells and inhibitory effect on pCaMKII γ (supplemental Table 1). MTT assay results showed that the IC50 values of BBM, BBD3, BBD12, BBD15, BBD24, and CP15 for leukemia cells were 5.43, 0.27, 1.2, 2.36, 0.5, and 8.34 μg/mL, respectively. Western blot analysis revealed that the IC50 values of BBM, BBD3, BBD12, BBD15, BBD24, and CP15 for inhibition of CaMKII γ activity were 6.0, 0.5, 1.5, 2.0, 0.45, and 8.0 μg/mL, respectively (supplemental Table 1). There was a significant correlation between IC50 values of the analogs for leukemia cell proliferation and inhibition of pCaMKII γ (Figure 6B; R2 = 0.9867), providing further evidence that berbamine-induced inhibition of leukemia cell proliferation is involved in blockage of CaMKII γ activity.

Correlation between inhibition of CaMKIIγ kinase activity and inhibition of leukemia cell proliferation by berbamine analogs. (A) Berbamine (BBM) and 2-methylbenzoyl berbamine (BBD24) inhibited phosphorylation of CaMKIIγ of leukemia cells. BBM or BBD24 treatment reduced phosphor-CaMKIIγ protein level, but not total CaMKIIγ protein level of K562 cells. Leukemia cells were treated with BBM or BBD24 at the indicated concentrations for 48 hours, and then total proteins were extracted for Western blot analysis for phosphor and total CaMKIIγ proteins. BBD5 was served as an inactive berbamine analog. (B) Correlation between inhibition of CaMKIIγ kinase and inhibition of cell proliferation by analogs of berbamine (BBM, BBD3, BBD12, BBD15, BBD24, and CP15; R2 = 0.9867). (C) Overexpression of CaMKII γ attenuated berbamine-induced growth inhibition of leukemia cells in vitro. Control or CaMKII γ overexpression cells were treated with BBM at the indicated concentrations for 48 hours, and then collected for analysis of cell viability by MTT assay, and phosphor and total CaMKIIγ proteins by Western blot. β-actin was used as loading control (* P < .01). (D) Overexpression of CaMKII γ reduced berbamine-induced growth inhibition of xenograft tumors in a dose-dependent manner (*P < .01). (E-F) hematoxylin-eosin (E) and PCNA (F) stain of xenograft tumors from NOD-SCID mice dosed with vehicle (top), BBM 50 mg/kg (middle), and BBM 100mg/kg (bottom). Left: A representative of control groups. Right: A representative of CaMKIIγ overexpression groups.

Correlation between inhibition of CaMKIIγ kinase activity and inhibition of leukemia cell proliferation by berbamine analogs. (A) Berbamine (BBM) and 2-methylbenzoyl berbamine (BBD24) inhibited phosphorylation of CaMKIIγ of leukemia cells. BBM or BBD24 treatment reduced phosphor-CaMKIIγ protein level, but not total CaMKIIγ protein level of K562 cells. Leukemia cells were treated with BBM or BBD24 at the indicated concentrations for 48 hours, and then total proteins were extracted for Western blot analysis for phosphor and total CaMKIIγ proteins. BBD5 was served as an inactive berbamine analog. (B) Correlation between inhibition of CaMKIIγ kinase and inhibition of cell proliferation by analogs of berbamine (BBM, BBD3, BBD12, BBD15, BBD24, and CP15; R2 = 0.9867). (C) Overexpression of CaMKII γ attenuated berbamine-induced growth inhibition of leukemia cells in vitro. Control or CaMKII γ overexpression cells were treated with BBM at the indicated concentrations for 48 hours, and then collected for analysis of cell viability by MTT assay, and phosphor and total CaMKIIγ proteins by Western blot. β-actin was used as loading control (* P < .01). (D) Overexpression of CaMKII γ reduced berbamine-induced growth inhibition of xenograft tumors in a dose-dependent manner (*P < .01). (E-F) hematoxylin-eosin (E) and PCNA (F) stain of xenograft tumors from NOD-SCID mice dosed with vehicle (top), BBM 50 mg/kg (middle), and BBM 100mg/kg (bottom). Left: A representative of control groups. Right: A representative of CaMKIIγ overexpression groups.

To further confirm these observations, we next overexpressed CaMKII γ with pRetroX-Tight-puro virus expressing CaMKII γ (supplemental Methods), and then determined if berbamine-induced proliferative inhibition is attenuated by CaMKII γ. As expected, overexpression of CaMKII γ significantly attenuated berbamine-induced growth inhibition of leukemia cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6C; P < .01). Consistently, Western blot results showed that phosphor-CaMKII γ protein level was well correlated with berbamine doses (Figure 6C bottom). In addition, overexpression of CaMKII γ enhanced proliferation of leukemia cells by 1.5 fold at 48 hours (Figure 6C right). To demonstrate that CaMKII γ is indeed the critical target of berbamine, we evaluated the effect of knockdown of CaMKII γ expression on CML cell growth and berbamine-mediated cell growth inhibition using shRNA (supplemental Methods). We found that partial knockdown of the kinase significantly inhibited the growth of CML cells (supplemental Figure 2A-B; P < .01) and sensitized CML cells to berbamine (supplemental Figure 3; P < .01). To validate these observations in vivo, we established a K562 leukemia xenograft model with overpression of CaMKII γ, and then tested the effects of CaMKII γ level on berbamine-induced tumor growth inhibition in vivo (supplemental Methods). In agreement with in vitro observations, overexpression of CaMKII γ not only markedly attenuated berbamine-induced growth inhibition of xenograft tumors, but also greatly promoted the growth of leukemia xenograft tumors (Figure 6D; supplemental Figure 4). Consistently, histologic analysis of xenograft tumors revealed that BBM-treated mice displayed necrosis with a decrease of cell nuclear proliferation antigen PCNA, whereas tumor tissues from control mice mainly consisted of proliferating tumor cells (Figure 6E-F). To verify whether berbamine inhibits CaMKII γ-dependent NF-κB, β-catenin, and Stat3 signaling pathways in vivo, we determined the effect of berbamine on signaling pathways of tumor cells after therapy using western blots. Consistent with observations in vitro, berbamine also inhibited CaMKII γ-dependent NF-κB, β-catenin and Stat3 signaling pathways, but not PKCα (supplemental Figure 5). Together, these findings clearly indicate that CaMKIIγ is a critical target of berbamine for its antileukemia activity.

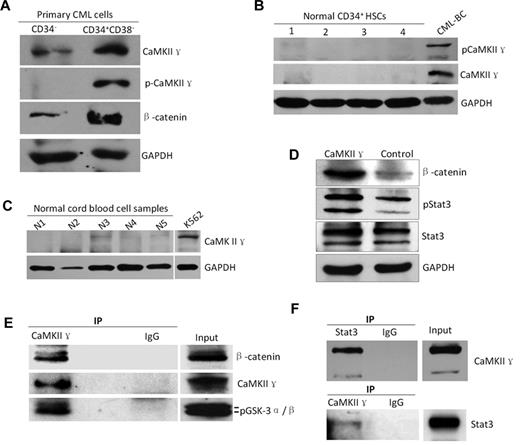

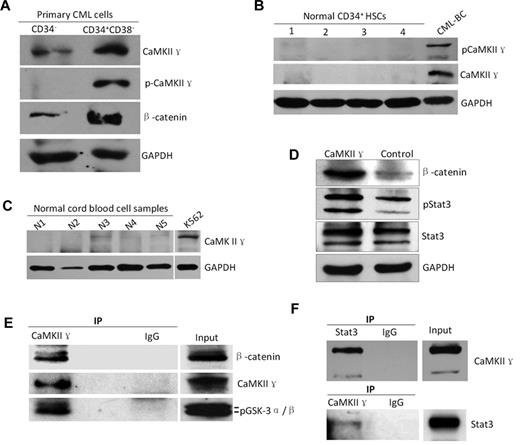

To determine whether CaMKII γ expression is associated with LSC, we analyzed CaMKII γ in CD34+/CD38− CML stem cells sorted by FACS from CML patients. Western blot analysis showed that both total and phosphor CaMKII γ proteins were highly expressed in the CD34+/CD38− CML LSCs, but low in CD34− CML cells (Figure 7A), and in CD34+ HSCs from healthy cord bloods (Figure 7B) and normal blood cells (Figure 7C). These data suggest that CaMKII γ might play a role in survival of LSCs. To substantiate these observations, we examined effect of CaMKII γ on β-catenin and Stat3 and found that CaMKII γ dramatically augmented β-catenin and phosphorylated Stat3 protein levels in leukemia cells (Figure 7D), suggesting that CaMKII γ can activate β-catenin and Stat3. To obtain biochemical evidence, coimmunoprecipitation was performed (supplemental Methods). Leukemia cell lysates were incubated with CaMKII γ antibody, and the immune complexes were then purified, separated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed with Western blot. We found that β-catenin and Stat3 were present in a protein complex immunoprecipitated by the CaMKII γ antibody (Figure 7E-F). These findings, together with previous studies,25,26 unravel that CaMKII γ is a critical molecular switch which could activate multiple LSC-related signaling networks including Wnt/β-catenin, Stat3, and NF-κB pathways.

High expression of CaMKIIγ is associated with leukemia stem cells of CML. (A-C) CaMKIIγ was highly activated in leukemia stem cells (LSCs) with a concomitant increased β-catenin(g) but not in normal hematopoietic cells (HSCs) and normal blood cells. LSCs and HSCs were sorted from primary CML samples of CML patients at blast crisis and normal cord blood samples, respectively, using FACS. (D) CaMKIIγ increased β-catenin and phospho-Stat3 proteins of leukemia cells. K562 cells were transfected with CaMKIIγ expression vector for 48 hours and then analyzed for β-catenin and Stat3 proteins by Western blot. (E-F) β-catenin and Stat3 protein physically interacted with CaMKIIγ in leukemia cells. Leukemia cell lysates were incubated with CaMKIIγ or Stat3 antibody, and the immune complexes were then purified, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with β-catenin, Stat3, or CaMKII γ antibody.

High expression of CaMKIIγ is associated with leukemia stem cells of CML. (A-C) CaMKIIγ was highly activated in leukemia stem cells (LSCs) with a concomitant increased β-catenin(g) but not in normal hematopoietic cells (HSCs) and normal blood cells. LSCs and HSCs were sorted from primary CML samples of CML patients at blast crisis and normal cord blood samples, respectively, using FACS. (D) CaMKIIγ increased β-catenin and phospho-Stat3 proteins of leukemia cells. K562 cells were transfected with CaMKIIγ expression vector for 48 hours and then analyzed for β-catenin and Stat3 proteins by Western blot. (E-F) β-catenin and Stat3 protein physically interacted with CaMKIIγ in leukemia cells. Leukemia cell lysates were incubated with CaMKIIγ or Stat3 antibody, and the immune complexes were then purified, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with β-catenin, Stat3, or CaMKII γ antibody.

Discussion

Since berbamine was first identified in 1940,42 it has been used in TCM for treating a variety of diseases from inflammation to tumors for decades.12,13 However, its molecular target and mechanism of action remains elusive to date. During past decades, berbamine was thought to be calcium channel blocker and calmodulin antagonist.16 Consistent with this, compound E6, an analog of berbamine, can inhibit calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) activity.33 In this study, we identified CaMKII γ as a specific and critical target of berbamine for its antileukemia activity. Targeting of berbamine to ATP-binding pocket of CaMKII γ, a critical molecular switch regulating NF-κB, Wnt/β-catenin and Stat3 essential for survival and self-renewal of leukemia stem/progenitor cells, and the consequent inhibition of the CaMKII γ activity provides a unified and coherent mechanism that can account for the unique and potent antileukemia activity of berbamine against LSC and T315I mutant Bcr-Abl clones. Because both our observations and other data reveal that CaMKII γ is a critical regulator of multiple signaling networks regulating the proliferation of leukemia cells, the effect of berbamine on the inhibitory activity of multiple cancer-related signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, Wnt/β-catenin, and Stat3 pathways, can be explained by the inhibition of CaMKII γ activity.

A striking finding from this work is that berbamine inhibited proliferation of both T315I mutant CML cells and stem/progenitor cells through apoptosis. Both of these 2 types of leukemia cells are highly resistant to TKIs and chemotherapy agents. Notably, we further observed that berbamine efficiently eliminated IM-resistant leukemia xenograft tumors in mice. These observations can be explained by berbamine-mediated inhibition of downstream targets of CaMKII γ: NF-κB, Wnt/β-catenin, and Stat3 pathways, which are constitutively activated in leukemia cells and essential for survival and self-renewal of leukemia stem/progenitor cells.

Surprisingly, our findings define as a central pathogenic role for the CaMKII γ in LSC. CaMKII γ is highly activated in leukemia stem/progenitor cells but not in normal hematopoietic cells. Moreover, our results demonstrate that CaMKII γ not only promotes proliferation of leukemia cells, but also activates β-catenin, NF-κB, and Stat3 networks essential for survival and self-renewal of LSC, which is consistent with our findings on the inhibitory activity of berbamine on β-catenin, NF-κB, and Stat3 networks, thus explaining the anti-LSC activity of berbamine.

Intriguingly, both the modeling of berbamine bound to the ATP binding pocket of CaMKII γ and its mutation analysis, together with the fact that berbamine analogs inhibited phosphorylation of CaMKII γ and ATP molecules attenuated berbamine-mediated CaMKII γ activity, suggest that this compound might compete with ATP molecule. If that proves to be true, it would be of extraordinary that the berbamine might be the first ATP-competitive inhibitor of CaMKII γ. Because current limited small-molecule inhibitors of CaMKII γ, such as KN93, inhibit this enzymatic activity through interfering with their binding to the Ca2+/calmoduling complex, and exert considerably less inhibition on CaMKII γ activity, this kinase activation markedly diminishes the requirement for Ca2+/calmodulin binding to maintain enzymatic activity once it has become activated.39,43 These findings might be of significant value in the targeted therapy of leukemia, because berbamine inhibits CaMKII γ activity via directly targeting its ATP-binding pocket, and may exert much greater activity in inhibiting tumor cell growth than KN93. The possibility cannot be rule out that berbamine also binds to substrate binding site, regulating the interaction of the kinase with corresponding substrates.

CaMKII γ belongs to a subfamily of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II.39,43 CaMKII γ regulates many fundamental cellular functions and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several diseases. Consistent with previous studies that CaMKII γ is a critical regulator of multiple cancer-related signaling pathways including NF-κB, Wnt/β-catenin, ERK, AKT, and Stat3 networks,43-46 our studies demonstrate that CaMKII γ acts as an important molecular switch which could activate multiple leukemia-associated signaling networks, such as β-catenin and Stat3 networks. Thus, inhibition of CaMKII γ by berbamine can account for berbamine-mediated down-regulations of multiple leukemia-related signaling networks and activation of cell death pathways. These findings also suggest that, as an inhibitor of CaMKII γ berbamine has potential to overcome drug resistance because of coactivation of multiple cancer-related signaling pathways.

Finally, the pharmacologic properties of berbamine can be optimized and improved by analyzing the structure-activity relationships governing inhibition of CaMKII γ and target selectivity. In addition, berbamine concentration in blood in rat could be up to 6.4 μg/mL,47 which is higher than that of its IC50 values for CML cells. Thus, we propose that berbamine and its analogs may represent a new type of anticancer agent by targeting CaMKII γ for the treatment of CML.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David D. Moore (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) for his constructive comments on this work; J. A. Wang, J. Huang, F. W. Xie, and H. X. Lai for their encouragements; and R. Frank for his critical reading of the paper.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30672381, 30873095, 81070420, and 81270601), Zhejiang Provincial Program for the Cultivation of High-level Innovative Health Talents, and the grants of the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Y206238, Y2080570, and Y2080210).

Authorship

Contribution: Y. Gu, T.C., Z.M., Y. Gan, X.X., X.G., H.Z., J.T., and Y.F. performed the in vitro experiments and nude mouse experiments; G.L. performed identification of target and IP experiment; H.L. performed docking modeling; G.X., L.H., X.Z., K.W., and S.Z. supervised the experiments and analyzed data; W.H. and R.X. conceived of the study, initiated, designed, supervised the experiments, and wrote the paper; and all authors discussed the results, commented on the paper, and approved the submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rongzhen Xu, Cancer Institute School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310009, China; e-mail:zrxyk10@zju.edu.cn; or Wendong Huang, Division of Gene Regulation and Drug Discovery, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope, Duarte, CA 91010; e-mail: whuang@coh.org.

References

Author notes

Y. Gu, T.C., Z.M, and Y. Gan contributed equally to this work.