Abstract

Diabetes mellitus has been associated with platelet hyperreactivity, which plays a central role in the hyperglycemia-related prothrombotic phenotype. The mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon are not established. In the present study, we investigated the role of CD36, a class-B scavenger receptor, in this process. Using both in vitro and in vivo mouse models, we demonstrated direct and specific interactions of platelet CD36 with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) generated under hyperglycemic conditions. AGEs bound to platelet CD36 in a specific and dose-dependent manner, and binding was inhibited by the high-affinity CD36 ligand NO2LDL. Cd36-null platelets did not bind AGE. Using diet- and drug-induced mouse models of diabetes, we have shown that cd36-null mice had a delayed time to the formation of occlusive thrombi compared with wild-type (WT) in a FeCl3-induced carotid artery injury model. Cd36-null mice had a similar level of hyperglycemia and a similar level of plasma AGEs compared with WT mice under this condition, but WT mice had more AGEs incorporated into thrombi. Mechanistic studies revealed that CD36-dependent JNK2 activation is involved in this prothrombotic pathway. Therefore, the results of the present study couple vascular complications in diabetes mellitus with AGE-CD36–mediated platelet signaling and hyperreactivity.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with an increased risk of pathologic arterial thrombosis, including myocardial infarction and stroke.1-3 Factors underlying this risk include accelerated atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, and platelet hyperreactivity, but the mechanisms linking diabetes to platelet hyperreactivity are not well understood.4,5 We and others have shown that platelets express receptors, including scavenger receptors and TLRs, that recognize endogenous and exogenous “danger signals,” the so-called danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs).6,7 We hypothesized that endogenous DAMPs that are generated in hyperlipidemia, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic inflammatory conditions could interact with platelets through these receptors to mediate platelet activation and induce a prothrombotic state. Indeed, in mouse models of hyperlipidemia and oxidant stress, we showed that oxidized LDL, a lipid-based DAMP, induced a prothrombotic state via interactions with the platelet type 2 scavenger receptor CD36.8-10 Similarly, oxidized phospholipids on the surface of cell-derived microparticles were shown to interact with platelet CD36 and promote thrombosis after oxidant injury to the arterial wall.11

Chronic hyperglycemia is a common feature of diabetes and is an important initiator of vascular complications, many of which have been related to vascular and inflammatory cell interactions with advanced glycation end products (AGEs).12,13 These heterogeneous, long-lived protein adducts are produced from a nonenzymatic chemical reaction between sugars and the amino groups of proteins.14 Circulating levels of AGEs, detected most commonly as hemoglobin A1C, are clinically important biomarkers used for monitoring diabetes therapy. On a pathophysiologic level, cellular interactions with AGEs induce biologic responses that have been linked directly to the development of diabetic vascular complications and that are mediated by specific cell-surface receptors. The best-studied AGE receptor is the Ig superfamily member receptor for AGE (RAGE), although limited studies suggest that scavenger receptors such as SR-A, SR-BI, and CD36 may also serve this function.15

Platelets from patients with DM have been reported to be hyperreactive, and this has been shown to be related to AGEs accumulation,8,16-18 but no evidence exists directly linking AGEs to platelet function, and no mechanisms have been defined. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that AGEs are DAMPs that interact specifically with platelet receptors to induce platelet hyperreactivity and a prothrombotic state. We found that although RAGE, SR-A, and SR-BI immunoreactivity could be detected in platelets, the binding of AGEs to platelets was mediated primarily by CD36, and that AGE-induced CD36 signaling resulted in enhanced platelet reactivity in vitro and enhanced arterial thrombosis in vivo. The latter was shown using mouse models of both type 1 and type 2 DM and direct injection of AGEs into healthy mice.

CD36, which was first described as platelet glycoprotein IV, is expressed constitutively at high levels on platelets and modulates platelet function by ligand-dependent triggering of a signaling pathway that involves specific Src family kinases, JNK family MAPK,10 and vav family guanine nucleotide exchange factors.8 Recent genetic studies revealed that platelet CD36 expression levels vary widely among individuals, and that this variation is correlated with platelet responsiveness to oxidized LDL and associated with the inheritance of specific CD36 gene polymorphisms.7 CD36 polymorphisms have also been associated with risk of acute myocardial infarction or stroke,19-21 suggesting that CD36 interaction with disease-specific DAMPs may be an important contributor to the pathogenesis of arterial thrombotic events. The results of the present study provide novel insights into the etiology of thrombotic complications in DM patients and define the CD36 pathway as a potential target for the development of novel antithrombotic therapeutic strategies.

Methods

Materials

AGE-BSA and BSA were from Cell Biolabs. The EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-Biotinylation kit was from Thermo Scientific. NO2+LDL and control NO2−LDL were generated using the MPO-hydrogen peroxide-nitrite system described previously.7 RAGE-blocking Ab (AF1179) and its control goat IgG were from R&D Systems.22 Streptozotocin (STZ) was from Sigma-Aldrich. RAGE immunoblotting Ab was from Abcam (ab30381), OSR-48 (AGE-receptor 1), galectin-3 (AGE receptor 3), SR-BI, SR-A, and actin Abs were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Phosphorylated JNK2 and total JNK2 Abs were from Cell Signaling Technology. Maltose-binding protein (MBP) was from New England Biolabs.

Carotid artery thrombosis model

All procedures on animals were approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Mice were housed in a facility fully accredited by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Care and in accordance with all federal and local regulations. C57Bl/6 or cd36-null mice backcrossed 10 times into a C57BL/6 background were subjected to common carotid artery injury by application of 10% FeCl3 for 1 minute as described previously.10,11,20 Rhodamine 6G (100μL at 0.5 mg/mL) was injected directly into the right jugular vein to label platelets, and thrombus formation was observed in real time using intravital fluorescence microscopy (Leica DMFLS) and video image capture (Streampix, Norpix). Time to complete cessation of blood flow was determined by visual inspection, and end points were set as cessation of blood flow for more than 30 seconds or observation of 30 minutes. In some studies, 50 μg of AGE-BSA dissolved in 50 μL of saline was injected through the right jugular vein 20 minutes before vessel injury.

DM models

Type I DM was induced in 10- to 12-week-old mice by 5 daily IP injections of STZ (50 mg/kg). Blood glucose levels were measured with the FreeStyle glucometer (Abbott Laboratories). To induce type 2 DM, mice were maintained on a high-fat, high-fructose diabetogenic diet (DBD; S3282; Bio-Serv; 35.5% lard and 32.7% sucrose and maltose dextrin) for 8 weeks beginning at 4 weeks of age after weaning. Control mice were fed either normal chow (2918; Harlan Teklad; 5% fat) or a “Western” diet (WD; 88137; Harlan Teklad; 42% calories from milk fat). The WD induces hyperlipidemia equivalent to the DBD but without hyperglycemia.

Platelet preparation and aggregometry assays

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg). Whole blood (600 μL) was collected from the inferior vena cava in 100 μL of 0.109M sodium citrate, and then diluted in 500 μL of Ca2+/Mg2+-free modified Tyrode buffer. Diluted platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was separated by centrifuging at 100g for 10 minutes at 22°C. Diluted platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was prepared by further centrifugation at 800g for 2 minutes. Platelets were counted using a hemocytometer and concentrations adjusted to 2 × 108/mL with PPP. CaCl2 and MgCl2 (both at a 1mM final concentration) were added immediately before platelet aggregation studies. Platelet aggregation in response to 1μM ADP was assessed at 37°C in a dual channel type 500 VS aggregometer (Chrono-log) with stirring at 100g. For human studies, PRP was prepared from normal donors and aggregometry assessed as described previously.7

Immunohistochemical staining

After carotid artery thrombosis assays, mice were killed and the thrombosed carotid arteries were harvested and embedded in optimal cutting temperature medium and frozen on dry ice. Cross-sections (5 μm) were prepared and stained with Abs to phospho-JNK2 or AGE using a DAB+ substrate chromogen system (Dako). Images were scored based on staining intensity, as described previously.10

Immunoblotting assay

Platelets were isolated by serial centrifugation and lysed in cell lysis buffer containing: 20mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 2mM EGTA, 5mM EDTA, 30mM NaF, 60mM β-glycerophosphate, 20mM Na4P2O7·10H2O, 1mM Na3VO4, and 1% Triton X-100 plus proteinase cocktail (R&D Systems). Twenty micrograms of protein was analyzed by immunoblot using standard techniques with Abs to the indicated proteins. Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-actin Ab as a loading control. Band intensities were determined using ImageJ Version 1.37 software, and then normalized to nonphosphorylated forms of the targeted protein or actin.

Flow cytometric AGE platelet-binding assay

Washed platelets were incubated with 5% human serum albumin for 30 minutes at 22°C. Platelets were then treated with different concentrations of biotin-labeled AGE-BSA or BSA as controls for 1-2 hours, followed by 5 μg/mL of avidin-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (Invitrogen), for 30 minutes before analysis by flow cytometry. In some cases, platelets were first incubated with 10 μg/mL of RAGE-blocking Ab22 or control IgG 45 minutes before being treated with biotin-labeled AGE-BSA, and all other incubation times were shortened as indicated.

CD36 fusion protein binding to AGEs

A recombinant CD36-MBP fusion protein containing the N-terminal extracellular domain of CD36 (aa 29-22) was expressed in bacterial cells and purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatography. The fusion protein or MBP control at 25 μg/mL was coated in PBS at 4°C overnight in wells of a 96-well plate. Wells were then incubated with different concentrations of AGE-BSA for 2 hours at 22°C. After washing, the amount of bound AGE-BSA was detected using an AGE ELISA kit (Cell Biolabs).

Plasma metabolic parameters

Tail vein blood from overnight fasted mice was collected between 9:00 and 10:00 am into EDTA-containing tubes and centrifuged at 2000g for 10 minutes to isolate plasma. Plasma was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until being assayed. Total cholesterol and nonesterified fatty acids were assayed using colorimetric kits (Wako). AGEs were analyzed by ELISA (Cell Biolabs). Nonstarving blood glucose levels were measured with the FreeStyle glucometer (Abbott).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least 3 times, and values are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical significance was evaluated by 1-way ANOVA or unpaired t test as appropriate using Prism Version 5.0 software (GraphPad).

Results

AGE binds to platelets via CD36

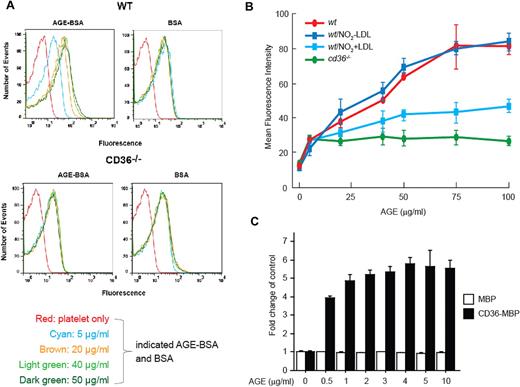

To determine whether AGEs could bind specifically to murine platelets, we developed a flow cytometry–based binding assay using biotinylated AGE-BSAs and avidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 488. As shown in Figure 1A (top panels), biotin-AGE-BSA bound to platelets from C57Bl/6 wild-type (wt) mice in a concentration-dependent manner, reaching a plateau at approximately 75 μg/mL. Binding of biotinylated “native” BSA, used as a control, was significantly lower than biotin-AGE-BSA and was not concentration dependent, which is consistent with a nonspecific effect. Because of the relatively high background binding of BSA, the signal for binding at the lowest concentration of AGE-BSA tested (5 μg/mL) was not distinguishable from that of the control. We next explored the possibility that CD36 may mediate the specific binding of AGEs to platelets. As shown in Figure 1A (bottom panels), no specific binding of AGE-BSA was seen to platelets from cd36-null mice. The degree of binding was similar to that of native BSA and was not concentration dependent.

AGE bind to platelets via CD36. (A) Isolated wt or cd36-null platelets were washed and incubated at 22°C with different concentrations of biotin-AGE-BSA or biotin-BSA as controls for 2 hours, followed by avidin-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate treatment for 1 hour. Platelets were then analyzed by flow cytometry to detect bound fluorescence. The histogram shown is representative of 3. (B) Increasing concentrations of AGE-BSA were added to wt or cd36-null platelets in the presence of either NO2+LDL or NO2−LDL (100 μg/mL). Bound fluorescence was detected as in panel A. (C) Wells in a 96-well ELISA plate were coated with recombinant CD36-MBP fusion protein or MBP (25 μg/mL in PBS) at 4°C overnight. Increasing concentrations of AGE-BSA were then added for 2 hours at 22°C, and bound material was detected with anti-AGE using a colorimetric ELISA assay. Data are presented as the mean fold change from control (± SEM); n = 3.

AGE bind to platelets via CD36. (A) Isolated wt or cd36-null platelets were washed and incubated at 22°C with different concentrations of biotin-AGE-BSA or biotin-BSA as controls for 2 hours, followed by avidin-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate treatment for 1 hour. Platelets were then analyzed by flow cytometry to detect bound fluorescence. The histogram shown is representative of 3. (B) Increasing concentrations of AGE-BSA were added to wt or cd36-null platelets in the presence of either NO2+LDL or NO2−LDL (100 μg/mL). Bound fluorescence was detected as in panel A. (C) Wells in a 96-well ELISA plate were coated with recombinant CD36-MBP fusion protein or MBP (25 μg/mL in PBS) at 4°C overnight. Increasing concentrations of AGE-BSA were then added for 2 hours at 22°C, and bound material was detected with anti-AGE using a colorimetric ELISA assay. Data are presented as the mean fold change from control (± SEM); n = 3.

To determine whether platelet activation influences AGE-BSA binding, we examined thrombin-stimulated platelets and found a modest increase in AGE-BSA immunofluorescence in both wt and cd36-null platelets compared with resting platelets. No significant differences were seen by comparing the increase in wt to that seen in cd36-null mice (data not shown), suggesting that platelet activation results in exposure of additional CD36-independent binding sites for AGEs.

We also found that preincubation of platelets with 100 μg/mL of NO2+LDL, a specific ligand for CD36,21 inhibited binding of biotin-AGE-BSA to resting platelets by up to 50% (Figure 1B), whereas the control NO2−LDL had no effect. These results support the conclusion that platelet-AGE interactions are mediated by CD36. The lack of full inhibition by saturating concentrations of NO2+LDL suggests that the recognition site for AGEs may not completely overlap that for oxidized phospholipids.

To demonstrate a direct interaction between CD36 and AGEs in cell-free conditions, we used a solid-phase immunologic binding assay in which ELISA plate wells were coated with a recombinant CD36-MBP fusion protein containing a large section of the CD36 N-terminal extracellular domain. As show in Figure 1C, AGEs bound to the CD36-MBP fusion protein in a concentration-dependent, saturable manner, with maximal binding seen at 2-5 μg/mL. AGE binding to MBP control peptide was not concentration dependent and was significantly lower than that to CD36-MBP.

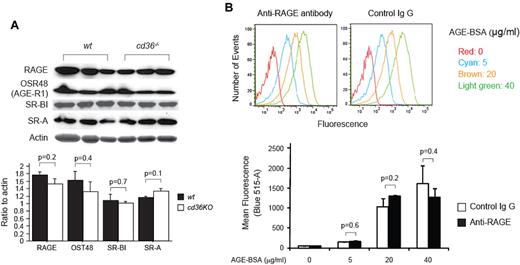

To determine the potential role of other AGE receptors in platelet activation, we analyzed platelet expression levels of candidate molecules, including RAGE. Although RAGE is widely expressed on vascular cells, its presence in platelets has not been established. Using an immunoblot assay, we detected immunoreactive RAGE in platelet lysates; no differences in expression levels were seen comparing cd36-null platelets with wt (Figure 2A). Similarly, AGE receptor 1 (AGE-R1, OST-48), SR-BI, and SR-A, all of which have been reported to bind to AGEs, were detected in mouse platelets with no differences in expression seen in cd36-null versus wt cells (Figure 2A). AGE-R3 was not detected in either wt or cd36-null platelets (not shown). These data demonstrate that the loss of AGE-binding capacity in cd36-null platelets was not because of an unexpected loss of other AGE receptors. To assess the role of RAGE in platelet-AGE binding, we preincubated wt platelets with 10 μg/mL of a well-characterized blocking mAb to RAGE.22 As shown in Figure 2B, blocking RAGE had no significant effect on biotin-AGE-BSA binding. These results strongly suggest that platelet-AGE binding is mediated primarily by CD36.

RAGE and other potential AGE receptors are expressed on mouse platelets. (A) Platelet lysates from wt and cd36-null mice were subjected to immunoblot assays with the indicated Abs. Membranes were stripped and reblotted with antiactin as a loading control. Band densities were measured and plotted as ratios to actin (n = 3). (B) Isolated wt platelets were incubated with 10 μg/mL of RAGE-blocking Ab or control IgG 45 minutes before being treated with biotin-labeled AGE-BSA, as described in Figure 1A. The histogram shown is representative of 4 and the bar graph shows mean fluorescence intensities (± SEM).

RAGE and other potential AGE receptors are expressed on mouse platelets. (A) Platelet lysates from wt and cd36-null mice were subjected to immunoblot assays with the indicated Abs. Membranes were stripped and reblotted with antiactin as a loading control. Band densities were measured and plotted as ratios to actin (n = 3). (B) Isolated wt platelets were incubated with 10 μg/mL of RAGE-blocking Ab or control IgG 45 minutes before being treated with biotin-labeled AGE-BSA, as described in Figure 1A. The histogram shown is representative of 4 and the bar graph shows mean fluorescence intensities (± SEM).

AGE enhances platelet reactivity ex vivo in a CD36-dependent manner

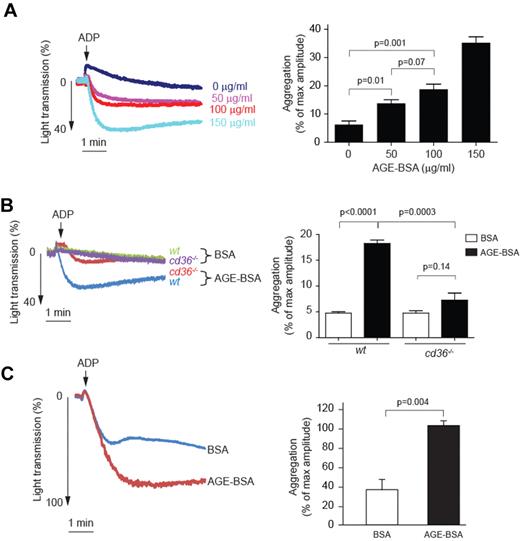

Having shown that AGEs bind to platelets via CD36, we investigated whether this interaction could influence platelet activation by assessing platelet aggregation in response to a low dose of ADP, a physiologically relevant agonist. As shown in Figure 3A, pretreatment of murine PRP with AGE-BSA increased the extent of platelet aggregation significantly in a concentration-dependent manner. This response was diminished significantly in platelets from cd36-null mice (Figure 3B), even at the highest AGE-BSA concentration tested. Native BSA had no statistically significant impact on aggregation responses in either wt or cd36-null platelets, demonstrating specificity. As shown in Figure 3C, AGE-BSA also significantly enhanced ADP-induced aggregation in human PRP.

AGE-BSA enhances platelet aggregation in a CD36-dependent manner. (A) Platelets were incubated with increasing concentrations of AGE-BSA for 30 minutes and then assessed for aggregation in response to low-dose ADP (1μM). On the left are representative tracings from n = 6, and on the right a bar graph showing mean amplitudes of aggregation expressed as the percentage of light transmission using control PPP (± SEM). (B) Platelets from wt or cd36-null mice were incubated with 100 μg/mL of AGE-BSA or BSA and then analyzed as in panel A (n = 4). On the right is a bar graph showing mean amplitudes of aggregation (± SEM). (C) PRP obtained from healthy donors was preincubated with 50μM of AGE-BSA or BSA control for 30 minutes and then stimulated with 5μM ADP. The left panel shows representative tracings; the right panel is a bar graph showing the mean amplitudes of aggregation (± SEM) of 3 independent experiments.

AGE-BSA enhances platelet aggregation in a CD36-dependent manner. (A) Platelets were incubated with increasing concentrations of AGE-BSA for 30 minutes and then assessed for aggregation in response to low-dose ADP (1μM). On the left are representative tracings from n = 6, and on the right a bar graph showing mean amplitudes of aggregation expressed as the percentage of light transmission using control PPP (± SEM). (B) Platelets from wt or cd36-null mice were incubated with 100 μg/mL of AGE-BSA or BSA and then analyzed as in panel A (n = 4). On the right is a bar graph showing mean amplitudes of aggregation (± SEM). (C) PRP obtained from healthy donors was preincubated with 50μM of AGE-BSA or BSA control for 30 minutes and then stimulated with 5μM ADP. The left panel shows representative tracings; the right panel is a bar graph showing the mean amplitudes of aggregation (± SEM) of 3 independent experiments.

Hyperglycemia enhances carotid artery thrombus formation in vivo in a CD36-dependent manner

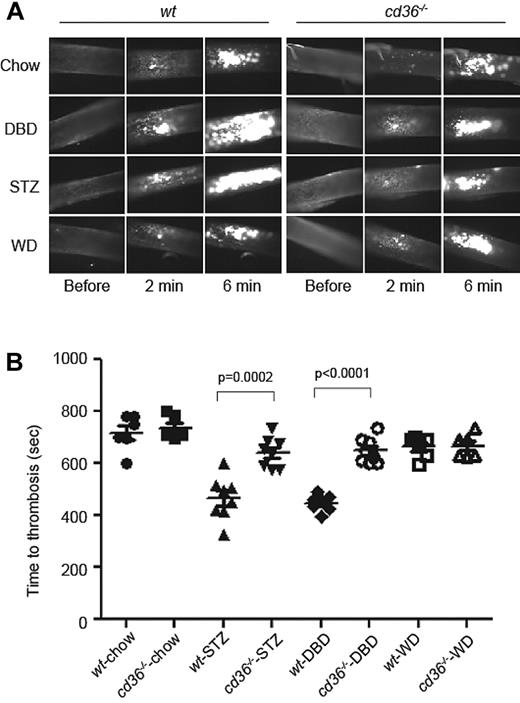

To test the in vivo relevance of these findings, we used an FeCl3-induced carotid injury model of arterial thrombosis in wt or cd36-null mice rendered chronically hyperglycemic either by diet-induced insulin resistance or drug-induced pancreatic islet destruction, models of type 2 and type 1 DM, respectively. Both interventions increased nonfasting blood glucose significantly. Three weeks after STZ treatment, nonfasting glucose levels stabilized at approximately 500 mg/dL in both wt and cd36-null mice. On the DBD, glucose levels stabilized at approximately 300 mg/dL with a small, but significant difference between the 2 strains (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Both DBD and STZ increased the serum levels of cholesterol and nonesterified fatty acids (supplemental Figure 1B), with no differences between wt and cd36-null mice. In these studies, we also used chow-fed and WD-fed mice as controls. The latter produced hypercholesterolemia comparable to that seen with the DBD and STZ, but without hyperglycemia.

As shown in Figure 4, induction of hyperglycemia in wt mice in both the STZ and DBD models was associated with significant shortening of carotid thrombosis times, with mean occlusion times of 467 ± 29.1 and 448.1 ± 11.8 seconds, respectively, compared with 717.7 ± 27.9 seconds in the chow-fed controls (P < .05). Similar to what we found previously,9,11 cd36 deletion had no impact on occlusion times in chow-fed or WD-fed mice at this dose of FeCl3. However, the absence of CD36 rescued the prothrombotic phenotype in both DM models, with mean occlusion times not significantly different from those in WD-fed animals (P = .39 and P = .49, respectively).

DM accelerates arterial thrombus formation in mice in vivo in a CD36-dependent manner. (A) Age-matched wt or cd36-null mice were maintained on chow, DBD, or WD for 8 weeks and then subjected to FeCl3-induced carotid artery injury to induce thrombus formation. STZ indicates chow-fed mice treated with STZ to induce pancreatic islet destruction and type 1 DM. Platelets were labeled in vivo by injection of rhodamine 6G and thrombi were imaged by fluorescence videomicroscopy. Representative images obtained at various time points are shown. (B) Time to occlusive thrombus formation was assessed using 6-8 mice per group.

DM accelerates arterial thrombus formation in mice in vivo in a CD36-dependent manner. (A) Age-matched wt or cd36-null mice were maintained on chow, DBD, or WD for 8 weeks and then subjected to FeCl3-induced carotid artery injury to induce thrombus formation. STZ indicates chow-fed mice treated with STZ to induce pancreatic islet destruction and type 1 DM. Platelets were labeled in vivo by injection of rhodamine 6G and thrombi were imaged by fluorescence videomicroscopy. Representative images obtained at various time points are shown. (B) Time to occlusive thrombus formation was assessed using 6-8 mice per group.

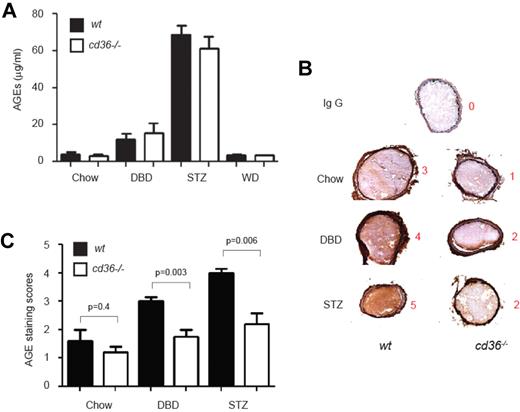

AGE accumulation in thrombi in diabetic mice is attenuated by cd36 deletion

We hypothesized that circulating AGE levels would increase in mice subjected to diet- or STZ-induced diabetes and that these would function as ligands for platelet CD36 to promote thrombosis. In the absence of CD36, we predicted that AGEs would not bind platelets and therefore would not accumulate within the thrombi formed after FeCl3-induced carotid injury. Plasma levels of AGEs, quantified by ELISA, were elevated by approximately 2-fold in DBD-fed mice and by approximately 12-fold in STZ-fed mice compared with the chow-fed group, but there were no differences between wt and cd36-null mice (Figure 5A), suggesting that CD36 has no effect on AGE generation. Immunohistochemical staining with polyclonal anti-AGE Ab of frozen sections prepared from dissected carotid artery thrombi showed that AGEs were readily detectable in the thrombi from diabetic mice (Figure 5B). Semiquantitative scoring of Ab staining intensity showed that cd36 deletion decreased AGE staining scores significantly (Figure 5B-C). Interestingly, AGE immunoreactivity was also seen in the vessel wall of the diabetic mice (Figure 5B), but CD36 deficiency did not affect the staining intensity. These data are consistent with CD36 function as the predominant AGE receptor on platelets, but not on vascular endothelium and smooth muscle, where, presumably, RAGE predominates.

AGE levels are increased in plasma and within thrombi in diabetic mice. (A) Plasma concentrations of AGEs in diet and STZ-treated wt or cd36-null mice were measured by ELASA. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 6-8 per group). (B) Carotid thrombi from wt or cd36-null mice induced as in Figure 3 were frozen, sectioned, and analyzed for the presence of AGEs by immunohistochemistry using anti-AGE IgG and a DAB+ substrate chromogen detection system. Brown color indicates immunoreactivity. Representative images are shown, and the red numbers indicate the intensity score of that image. (C) Mean AGE-staining scores (± SEM) of 5 sections from each thrombus (n = 5 per group).

AGE levels are increased in plasma and within thrombi in diabetic mice. (A) Plasma concentrations of AGEs in diet and STZ-treated wt or cd36-null mice were measured by ELASA. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 6-8 per group). (B) Carotid thrombi from wt or cd36-null mice induced as in Figure 3 were frozen, sectioned, and analyzed for the presence of AGEs by immunohistochemistry using anti-AGE IgG and a DAB+ substrate chromogen detection system. Brown color indicates immunoreactivity. Representative images are shown, and the red numbers indicate the intensity score of that image. (C) Mean AGE-staining scores (± SEM) of 5 sections from each thrombus (n = 5 per group).

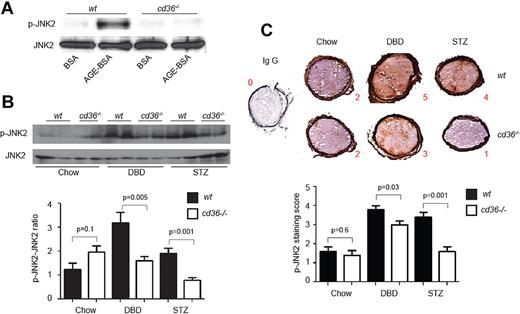

CD36-dependent platelet signaling is induced by AGEs in vitro and hyperglycemia in vivo

CD36-mediated platelet activation in response to oxLDL or cell-derived microparticles is mediated by a signaling pathway that requires activation of the MAPK JNK.10 To show that this same pathway can be activated by AGEs, we treated platelets with AGE-BSA and demonstrated markedly increased JNK2 phosphorylation in wt platelets but not in cd36-null platelets (Figure 6A). Native BSA had no effect on JNK2 phosphorylation. We then assessed JNK2 phosphorylation status in circulating platelets isolated from both wt and cd36-null mice after induction of diabetes with DBD or STZ, and found that both treatments increased basal platelet JNK2 phosphorylation levels by 2- to 3-fold compared with control mice (P < .05). This response was not seen in platelets from cd36-null mice (Figure 6B). These data suggest that the CD36 signaling pathway is activated in “resting” platelets in diabetic mice. Immunohistochemical staining for p-JNK2 in dissected carotid artery thrombi demonstrated that thrombi from diabetic cd36-null mice had 20%-50% lower staining-intensity scores than those from wt animals (Figure 6C).

JNK2 phosphorylation levels are increased in platelets and thrombi in diabetic mice. (A) Washed platelets from wt or cd36-null mice were treated with AGE-BSA or BSA control (50 μg/mL) for 15 minutes. Lysates were then assessed by immunoblot using anti–phospho-JNK2 Ab. An Ab to total JNK2 was used as a loading control. Blot is representative of 4. (B) Platelets from chow-, DBD-, and STZ-fed wt or cd36-null mice were analyzed by immunoblot as in panel A. A representative immunoblot of 4 is shown. The bar graph shows the ratio of phospho-JNK2 (p-JNK2) to total JNK2. (C) Representative images of thrombosed carotid arteries from chow-, DBD-, and STZ-fed wt or cd36-null mice stained with anti–p-JNK. Bar graph shows staining intensity scores for p-JNK (n = 5 mice per group).

JNK2 phosphorylation levels are increased in platelets and thrombi in diabetic mice. (A) Washed platelets from wt or cd36-null mice were treated with AGE-BSA or BSA control (50 μg/mL) for 15 minutes. Lysates were then assessed by immunoblot using anti–phospho-JNK2 Ab. An Ab to total JNK2 was used as a loading control. Blot is representative of 4. (B) Platelets from chow-, DBD-, and STZ-fed wt or cd36-null mice were analyzed by immunoblot as in panel A. A representative immunoblot of 4 is shown. The bar graph shows the ratio of phospho-JNK2 (p-JNK2) to total JNK2. (C) Representative images of thrombosed carotid arteries from chow-, DBD-, and STZ-fed wt or cd36-null mice stained with anti–p-JNK. Bar graph shows staining intensity scores for p-JNK (n = 5 mice per group).

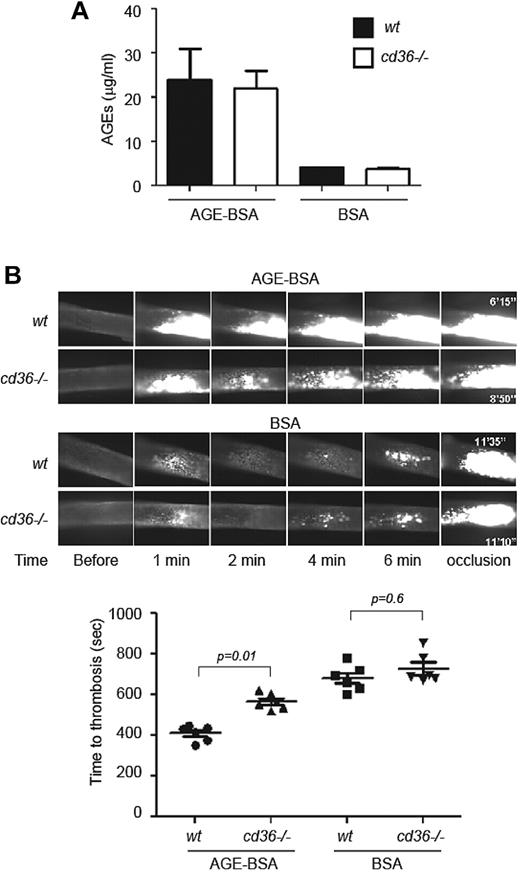

Systemic infusion of AGEs accelerates thrombosis in a CD36-dependent manner

To demonstrate a direct effect of AGEs on thrombus formation in vivo and to eliminate potential confounding effects from metabolic disturbances in the diabetic models unrelated to AGEs, we injected 50 μg of AGE-BSA or native BSA via the jugular vein into wt and cd36-null mice 20 minutes before subjecting them to FeCl3-induced carotid injury. Injection of this amount of AGE-BSA into either mouse strain resulted in final plasma AGE concentrations of approximately 25 μg/mL, similar to levels seen in DBD-fed mice (Figure 7A). AGE-BSA injection shortened carotid artery occlusion times in wt mice (P < .0001 vs BSA-wt; Figure 7B). The degree of shortening was similar to that seen in the diabetic mice. Deletion of cd36 significantly protected mice from the prothrombotic effect of AGE-BSA injection (P < .0001 vs BSA-cd36−/−), although the protection was not complete.

Deletion of cd36 rescues accelerated thrombus formation induced by AGE injection in vivo. (A) AGE-BSA or BSA was injected directly into wt or cd36-null mice through the jugular vein and allowed to circulate for 20 minutes. Plasma levels of AGEs were then assessed by ELISA. Graph shows means ± SEM. (B) Mice treated as in panel A were subjected to FeCl3-induced thrombosis as in Figure 3. Representative images of intracarotid thrombi at the indicated time points are shown (top) and the bar graph shows the mean times to occlusive thrombosis (n > 6 for all groups).

Deletion of cd36 rescues accelerated thrombus formation induced by AGE injection in vivo. (A) AGE-BSA or BSA was injected directly into wt or cd36-null mice through the jugular vein and allowed to circulate for 20 minutes. Plasma levels of AGEs were then assessed by ELISA. Graph shows means ± SEM. (B) Mice treated as in panel A were subjected to FeCl3-induced thrombosis as in Figure 3. Representative images of intracarotid thrombi at the indicated time points are shown (top) and the bar graph shows the mean times to occlusive thrombosis (n > 6 for all groups).

Discussion

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with DM. DM accelerates the atherosclerotic process, and patients with DM also have a higher risk of thrombotic and recurrent ischemic events than non-DM patients.23,24 Several factors contribute to the diabetic prothrombotic state, including an impaired procoagulant/anticoagulant balance, endothelial dysfunction, and platelet hyperreactivity.2,25 Mechanisms believed to contribute to the “diabetic platelet” phenotype include hyperglycemia, impaired insulin signaling, and abnormalities associated with disordered metabolism, such as obesity, dyslipidemia, and inflammation.5 Although the mechanisms by which hyperglycemia causes platelet hyperreactivity are not well understood, studies have implicated decreased platelet membrane fluidity, osmotic effects, protein kinase C activation, and advanced glycation of circulating proteins and LDL.26-30 The biochemical process of advanced glycation, which is accelerated in DM as a result of chronic hyperglycemia and increased oxidative stress, has been associated with platelet hyperreactivity,13,16,31,32 but the mechanisms have not been defined.

AGEs exert biologic effects mainly by engaging specific receptors, of which RAGE is the mostly extensively studied. RAGE is minimally expressed in normal tissue and vasculature, but is up-regulated on endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, mononuclear phagocytes, and lymphocytes33,34 when AGEs accumulate.33,35,36 A key mediator of RAGE signaling is NF-κB, which translocates to the nucleus, where it increases the transcription of key proinflammatory and prothrombotic genes.37 However, platelets do not have nuclei, so the role of this signaling pathway in them is not clear. Our data show that although platelets express RAGE, treatment of platelets with a RAGE-blocking Ab did not affect the specific binding of AGE-BSA to the platelet surface, suggesting that it does not play a significant role in AGE-mediated platelet responses. The family of AGE receptors known as AGE-R1, AGE-R2, and AGE-R3 are also not likely to be involved, because they function mainly as clearance receptors38,39 and are not known to induce signal transduction. In light of this, we focused our studies on CD36, which in a limited number of studies has been suggested to function as a potential AGE receptor.40,41

Using direct AGE-binding assays, platelet function assays, and in vivo models of arterial thrombosis with wt and cd36-null platelets, we found that AGEs bound to recombinant CD36-MBP fusion protein in vitro and that platelet CD36 serves as a specific prothrombotic receptor for AGE. AGE-BSA bound to wt but not to cd36-null platelets in a concentration-dependent manner, and binding was partially inhibited by NO2+LDL, a specific CD36 ligand. In addition, AGE-BSA dose-dependently increased low-dose ADP-induced platelet aggregation. These data are consistent with an earlier study showing that platelet aggregation in response to the weak agonist serotonin was also increased in response to AGEs.16 Our data also show that the enhancing effect of AGEs on platelet activation was CD36 dependent. The lack of complete inhibition of the AGE effect by NO2+LDL and the slightly greater (P = .14) aggregation response of cd36-null platelets compared with wt when treated with AGE-BSA make it impossible to rule out a minor role for additional AGE receptors on platelets. It is possible that our AGE-BSA–binding assay was not sensitive enough to detect low-level binding to the other platelet AGE receptors on cd36-null platelets.

The potential clinical relevance of our findings is supported by in vivo evidence using well-established mouse models of arterial injury and thrombosis.10,11,20 Using diabetes models that produced levels of circulating endogenous AGEs similar to those reported in human diabetic patients, as well as a model of direct infusion of AGE-BSA, in the present study, we found that CD36 deficiency “rescued” the prothrombotic phenotype associated with these interventions without affecting the circulating AGE levels. Despite similar circulating AGE levels, significantly less AGEs accumulated in carotid thrombi from cd36-null mice compared with those in wt animals, as assessed by semiquantitative immunohistochemistry. The prothrombotic phenotype in these models was dramatic, with shortening of thrombosis times by approximately 40%. The rescue by cd36 deletion was nearly complete in the DM models, but only partial in the direct AGE infusion model. The latter may be related to the acute effects of AGEs, such as AGE-induced oxidative stress and decreased nitric oxide formation, which are mediated by RAGE signaling on vascular cells other than platelets.18,31,42

Hyperlipidemia often accompanies hyperglycemia in patients with DM. We and others have shown that diet-induced hyperlipidemia in apoe-null mouse models induces a prothrombotic state associated with the generation of oxLDL and CD36-mediated platelet hyperreactivity.8-10 To separate the potential confounding effect of hyperlipidemia in the present study, we used WD-fed C57Bl/6 mice as an additional control. This diet induced a similar level of hyperlipidemia as the DBD, but unlike in the apoe-null background, the lipid levels and, presumably, the degree of oxidant stress were not enough to induce a prothrombotic state. These data suggest that hyperglycemia was the driving force behind the prothrombotic state in the DM models, a conclusion supported by the AGE-BSA infusion experiment.

Platelets from patients with DM are characterized by dysfunction of several signaling pathways at the level of both receptor and downstream intracellular signaling partners.43 Our recent work has shown that the platelet CD36-signaling pathway is mediated by the MAPK JNK, as well as by the Src kinases Fyn and Lyn, and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav.10 In the present study, we have shown that exposure of platelets to AGE-BSA ex vivo induced JNK phosphorylation in wt but not cd36-null platelets dramatically, and also that circulating “resting” platelets from mice with both DBD- and STZ-induced DM had increased basal levels of phosphorylated JNK. This was not seen in platelets from cd36-null mice, suggesting that the CD36-signaling pathway was activated chronically by hyperglycemia. In addition, immunohistochemical analysis confirmed the increased amount of p-JNK within thrombi from diabetic wt mice compared with cd36-null mice.

In summary, the results of the present study define a novel mechanism by which DM and hyperglycemia trigger a CD36-mediated platelet-signaling pathway leading to hyperresponsiveness to low concentrations of agonists. This could create a state in which circulating platelets are “primed” to respond to injury and thus promote enhanced thrombus formation. Targeting this pathway could lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies to prevent thrombotic complications in patients with high-risk conditions such as DM.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mette Johansen for providing the CD36-MBP fusion protein.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P50HL81011 to R.L.S. and 5T32HL007914 to W.Z.)

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: W.Z. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments and wrote the manuscript; W.L. performed the immunoblots shown in Figure 2, provided input on the experimental design, and wrote the manuscript; and R.L.S. contributed to the overall project design and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Roy L. Silverstein, MD, Chair, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, 9200 W Wisconsin Ave, Suite C5038, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: rsilverstein@mcw.edu.