Abstract

Cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD) is highly effective in multiple myeloma. We treated patients with light chain amyloidosis (AL) before stem cell transplantation (ASCT), instead of ASCT in ineligible patients or as salvage. Treatment was a combination of bortezomib (1.5 mg/m2 weekly), cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2 orally weekly), and dexamethasone (40 mg weekly). Seventeen patients received 2 to 6 cycles of CyBorD. Ten (58%) had symptomatic cardiac involvement, and 14 (82%) had 2 or more organs involved. Response occurred in 16 (94%), with 71% achieving complete hematologic response and 24% a partial response. Time to response was 2 months. Three patients originally not eligible for ASCT became eligible. CyBorD produces rapid and complete hematologic responses in the majority of patients with AL regardless of previous treatment or ASCT candidacy. It is well tolerated with few side effects. CyBorD warrants continued investigation as treatment for AL.

Introduction

Light chain amyloidosis (AL) is characterized by immunoglobulin light chain–derived amyloid deposits that are associated with monoclonal expansion of plasma cells or lymphoplasmacytic cells.1,2 Median overall survival from diagnosis is approximately 3 years, but with clinically overt cardiac involvement this is reduced to 1 year.3,4 Although alkylator-based, conventional chemotherapy has been the standard of care, it has limited success.5,6 High-dose melphalan and stem cell support may confer benefit and longer survival, but many patients are not eligible for this treatment modality because of comorbidities or extensive cardiac involvement.7-9 Because of success in myeloma, recent investigations have explored the use of novel agents, including thalidomide, lenalidomide, and bortezomib, as treatment for AL.10-15

We have recently reported on the combination of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (CyBorD) as a very active regimen against multiple myeloma, producing rapid and profound responses.16 This regimen is tolerable and manageable, major toxicity is peripheral neuropathy, although this has been dramatically reduced when bortezomib is given on a weekly rather than twice weekly schedule.17 We report here on the use of CyBorD as initial therapy before autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), as an alternative to high-dose therapy for those deemed ineligible, and as salvage for those with prior therapy.

Methods

Patients

This is a retrospective analysis of patients with confirmed and symptomatic AL who were treated with CyBorD at our institution from 2007 to 2010. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Patients with newly diagnosed or previously treated AL were eligible for analysis, whether they were candidates for ASCT or not. Patients were required to have immunohistochemical stain demonstrating AL or confirmation by mass spectroscopy.18 Organ involvement and response were determined as previously described.19 Complete hematologic response (CR) is defined as normalization of the light chain ratio with no monoclonal protein by immunofixation; partial response is 50% reduction in M-spike or absolute light chain level.

Treatment

Treatment scheme consisted of bortezomib 1.5 mg/m2 weekly (n = 15), or 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 every 28 days (n = 2), cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2 orally weekly), and dexamethasone (40 mg weekly). All patients were given antiviral prophylaxis.

Results and discussion

Seventeen patients were treated with 2 to 6 cycles of CyBorD (median, 3 cycles). Clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Clinical features were typical of patients with AL, with 82% kidney and 58% heart involvement. Of note, all 10 patients with symptomatic cardiac involvement had elevated levels of both cardiac biomarkers (troponin T and B-natriuretic peptide). Two or more organs were involved in 14 (82%). Ten patients (58%) were treatment naive. Previous treatment included dexamethasone (100%), lenalidomide (57%), melphalan (43%), cyclophosphamide (29%), thalidomide (14%), or liposomal doxorubicin (14%).

Hematologic response

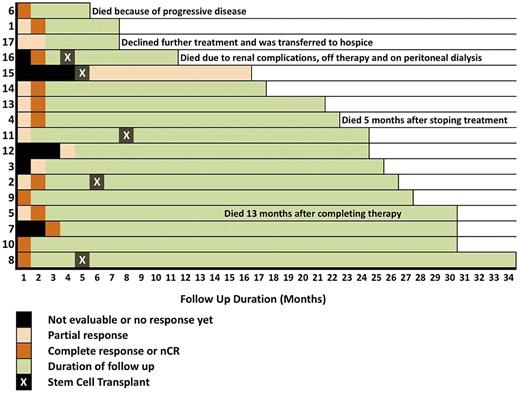

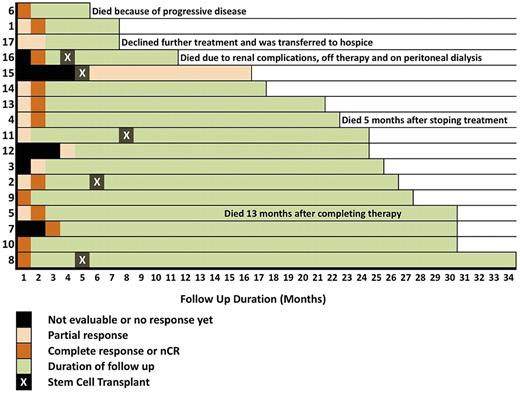

Hematologic response was seen in 94% (16 of 17), with 12 (71%) achieving a CR and 4 (24%) a partial response (PR). One patient had stable disease but went on to ASCT and then achieved a PR. Median time to response was 2 months (Figure 1).

Organ response

Kidney response was assessable in 12 of 14, and 6 (50%) had a 50% decrease in proteinuria. Two of these had normalization of urinary protein level. Interestingly, 3 patients initially considered to be transplant ineligible became eligible after therapy with CyBorD.

All 10 patients with cardiac involvement had baseline B-type natriuretic peptide (normal < 58 pg/mL) and troponin T (normal < 0.03 pg/mL) studies; mean B-type natriuretic peptide was 1008.2 pg/mL (range, 294-1987 pg/mL) at baseline, and mean troponin was 0.14 pg/mL (range, 0.02-0.40 pg/mL). Of the 7 patients monitored for cardiac response by these biomarkers, 5 improved (with 3 normalized) while 2 progressed on therapy.

Toxicity

All patients were assessed for toxicity. Only 2 patients experienced grade 1 or 2 peripheral neuropathy (no grade 3 or 4). This is probably indicative of weekly administration of bortezomib in most patients (15 of 17), although one of these received the weekly regimen. Hematologic toxicity was minimal without the need for blood or platelet transfusions. Infections requiring hospitalization occurred in 2 patients (1 Clostridium difficile colitis and 1 pneumonia); 1 patient developed localized herpes zoster.

Outcomes

With a median follow-up of 21 months, 12 of 17 patients remain alive. Of the 12 patients achieving a CR, 9 (75%) remain in CR status with a median duration of response of 22.0 months (range, 5-30 months). The 12 patients who achieved a CR did so after a median time of 2 months. The median serum-free light chain before therapy initiation was 117.7 (10.2-689.0) and came down to a normal range in 10 of 17 persons (58.8%).

Here we show that CyBorD produces a rapid, deep, and durable response in the majority of patients with AL, even in the setting of cardiac and multiorgan disease. After a median of 3 cycles, 94% of patients have had a hematologic response, with 71% CR and 50% kidney response. This very high response rate is significant, especially in light of other studies showing that hematologic response is associated with long-term survival.20 Given the time delays of stem cell transplantation, CyBorD may be the fastest and most effective regimen to be reported. This compares favorably with other bortezomib and dexamethasone studies; one reported a response rate of 54% with 31% CR,21 and the other had 94% response with 44% CR.22 The increase in CR seen with CyBorD may be partially attributed to the addition of cyclophosphamide.

There are several attractive features to CyBorD. The weekly dosing of all 3 agents not only contributes to its convenience but, as with myeloma, appears to have the same efficacy with reduced rates of neuropathy as twice weekly dosing.17 Indeed, only 2 patients had grade 1 or 2 neuropathy. Furthermore, with introduction of subcutaneous bortezomib, CyBorD may be even more convenient. Oral administration of cyclophosphamide is well tolerated (no alopecia and minimal myelosuppression) and may even be superior to the intravenous route, as its longer half-life yields longer periods of exposure to slowly dividing cells. Dosing of dexamethasone may also be easily altered: in patients in whom 40 mg may be expected to cause toxicity, 20 mg may be considered initially or as dose reduction.

CyBorD can be administered to patients both eligible and ineligible for ASCT without concerns for stem cell toxicity. Three patients in our cohort who were initially ineligible for ASCT became candidates after treatment with CyBorD. It is also a legitimate combination in relapsed disease, seeking to optimize alkylator and proteasome inhibitor activity together. As with the Palladini et al study using lenalidomide,15 refractoriness to melphalan can be overcome with CyBorD. Indeed, those previously treated had been heavily so: more than half had had lenalidomide and nearly half had melphalan.

One remaining question is whether patients who achieve CR with CyBorD should still undergo ASCT (with its risks) after induction. As with myeloma, until addressed prospectively, our clinical practice is still to proceed to transplantation in eligible cases. In a recent retrospective analysis of all patients treated at Mayo Clinic, 10-year median survival for those achieving a CR had not been reached; for those with PR, it was 107 months; and for those with less than PR, it was 32 months,20 emphasizing the importance of CR. With 71% CR, CyBorD holds the promise of contributing to curing a larger proportion of AL patients. Perhaps novel methods for minimal residual disease determination coupled with normalization of light chains will pave the way for medical therapies, such as CyBorD, to become sole treatment for AL.

As a retrospective review, this study has weaknesses, including selection bias, small numbers, variable entry criteria, and slight differences in treatment regimen. There remains much to learn about novel therapies in AL and their combination with conventional chemotherapy. The optimal duration, in particular, of CyBorD is yet to be determined. Although a small cohort, this study provides evidence for its profound activity and the need for further study in prospective randomized trials.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.R.M., V.H.J.-Z., S.R.S., and R.F. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. N.B. and J.S. performed research and analyzed data; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: V.H.J.-Z. has received honoraria from Janssen-Ortho. A.K.S. has received honoraria from Celgene, is a consultant for Onyx, and receives research funding from Millenium. R.F. is a consultant for Genzyme, Medtronic, BMS, AMGEN, Otsuka, and Intellikine, receives research funding from Cylene, is a consultant for (and receives research funding from) Celgene, and receives research funding from (prognosticated on FISH probes in myeloma for) and receives patents and royalties from Onyx. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joseph R. Mikhael, Mayo Clinic Scottsdale, 13400 E Shea Blvd, Scottsdale, AZ 85259; e-mail: mikhael.joseph@mayo.edu.