Abstract

Although HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease (HIV-MCD) is not classified as an AIDS-defining illness, mortality is high and progression to lymphoma occurs frequently. At present, there is no widely accepted recommendation for the treatment of HIV-MCD. In this retrospective (1998-2010), multicentric analysis of 52 histologically proven cases, outcome was analyzed with respect to the use of different MCD therapies and potential prognostic factors. After a mean follow-up of 2.26 years, 19 of 52 patients died. Median estimated overall survival (OS) was 6.2 years. Potential risk factors, such as older age, previous AIDS, or lower CD4 T cells had no impact on OS. Treatment was heterogeneous, consisting of cytostatic and/or antiviral agents, rituximab, or combinations of these modalities. There were marked differences in the outcome when patients were grouped according to MCD treatment. Patients receiving rituximab-based regimens had higher complete remission rates than patients receiving chemotherapy only. The mean estimated OS in patients receiving rituximab alone or in combination with cytostatic agents was not reached, compared with 5.1 years (P = .03). Clinical outcome and overall survival of HIV-MCD have markedly improved with rituximab-based therapies, considering rituximab-based therapies (with or without cytostatic agents) to be among the preferred first-line options in patients with HIV-MCD.

Introduction

Compared with the benign, localized hyperplasia of lymphatic tissue, first described by Castleman et al in 1956,1 HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease (HIV-MCD) is a malignant lymphoproliferative disease. Although not classified as a lymphoma or AIDS-defining illness, mortality is high and progression to lymphoma occurs frequently.2,3 There is some evidence that the incidence of HIV-MCD is increasing, particularly in older persons with well-preserved immune function.4

The pathogenesis of HIV-MCD is not completely understood. There is a close association to infection with human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8), which can cause cytokine dysregulation by encoding a viral homolog of IL-6.5-7 However, it remains unclear why only a small proportion of persons with active HIV/HHV-8 coinfection develop HIV-MCD. The extent of immunodeficiency may vary considerably, and HIV-MCD, unlike Kaposi sarcoma (KS), is not associated with a reduced HHV-8–specific immune response.8

At present, there is no widely accepted recommendation for the treatment of HIV-MCD.9,10 Reports on the effects of antiretroviral therapy (ART) have been inconsistent,11-14 suggesting that, in contrast to KS, ART alone may not be sufficient to prevent or to treat HIV-MCD in the majority of patients. Apart from ART, numerous treatment attempts for HIV-MCD have been reported, including cytostatic, antiviral, or immune-modulating agents. However, none of these options has yet been tested in a randomized, controlled trial.

In the present study, we analyzed the outcome of patients with HIV-MCD in a large cohort. We were interested not only in the patients' characteristics but also in applied MCD therapies and potential prognostic factors, to gain insight into the “real-life scenario” in HIV-infected persons who have developed this rare disease over the past decade.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed of all histologically proven cases of HIV-MCD with clinical features of active disease seen in the 11 participating centers from January 1998 to July 2010. HIV-infected patients were identified by computed database analysis in each center. Patients with clinically assumed, but not histologically verified, MCD diagnosis were excluded from the analysis. An anonymized questionnaire was developed to extract information from the medical records so that a centralized computer database could be established. The questionnaire elicited data concerning demographic characteristics, AIDS history, hematologic, immunologic, and virologic parameters, and clinical features. In addition to detailed treatment of HIV infection and MCD, remission stage of MCD was also evaluated. A complete remission was defined as the absence of any MCD symptoms for at least 3 months (“sustained” for > 12 months), or, if detailed monitoring by radiologic procedures was not available, symptom-free without need for re-treatment (as judged by the treating physician). Treatment of HIV-MCD included cytostatic agents (“C,” given as monotherapy or in combination), antivirals (“V,” ie, foscarnet, cidofovir, or valgancyclovir), or immunotherapy with rituximab (“R”).

Fisher exact text was used for comparison of frequencies. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for unpaired comparison of continuous variables. A P value of > .05 was considered statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier survival statistics were used to evaluate overall survival (OS). OS was defined as the period from HIV-MCD diagnosis to death from any cause or the last contact (which was censored). In the univariate analysis, diverse factors present at the MCD diagnosis, such as age (> 50 years vs < 50 years), a prior AIDS related event (yes vs no), CD4 T-cell counts (< vs > 200 CD4 T cells/μL), HIV-RNA (< 400 vs > 400 copies/mL), hemoglobin (< 10 vs > 10 g/dL), thrombocytes/platelet count (< 150 vs > 150/μL), and time period between first symptoms and diagnosis of HIV-MCD (< 1 vs > 1 year) were analyzed. To reduce the possible bias through confounding by indication as a result of association between patient's pretreatment condition and physician's treatment decision, only patients starting an antiviral, cytostatic, or immune-modulating MCD treatment were included in the OS analysis.

Results

A total of 52 patients were included in the analysis. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. By far, the most frequent HIV transmission risk was homosexual contact (90%). Only 1 patient reported intravenous drug use, and in one patient the transmission risk was unknown. Of the 2 women in the cohort, 1 came from a country endemic for HIV whereas the other woman acquired HIV by heterosexual contact. Of the 35 patients with available data on hepatitis infection status, 2 (6%) and 23 (66%) had evidence for active or prior hepatitis B, respectively. One patient had an active hepatitis C and one had evidence for a prior hepatitis C infection.

At the time of MCD diagnosis, the degree of immune deficiency, measured by CD4 T-cell count, was only moderate in most patients. However, almost two-thirds had a prior AIDS-defining illness, mainly KS (Table 1). Consecutively, 80% of patients had a current or prior antiretroviral therapy at the time of MCD diagnosis. Of all patients treated with ART, 50% had a plasma HIV-RNA of > 50 copies/mL for a mean time period of 0.81 years.

With respect to the clinical signs, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and fever were present in almost every patient. Peripheral edema and pulmonary symptoms were also frequent findings as well as hematologic complications. A grade II-IV anemia (hemoglobin of < 9.5 g/dL) and a grade II-IV thrombocytopenia (< 75/μL) were found in 48% and in 20% of the patients, respectively. Of note, at least 6 patients (12%) developed severe renal insufficiency, requiring continuous dialysis in 5 patients. C-reactive protein was elevated in all patients during the course of the disease, with a median maximum of 168 mg/L.

Treatment of HIV-MCD was very heterogeneous, consisting of cytostatic agents (C), antiviral agents (V), and rituximab (R) or the combinations of these modalities. All patients had had several MCD “flares,” consisting of fever, lymphadenopathy, and night sweat within the last 6 weeks before treatment. The individual outcomes according to different HIV-MCD treatment are shown in Table 2. Of the 47 patients who were evaluable for the outcome analysis after first-line treatment, 22 (47%) achieved a sustained complete remission of HIV-MCD for at least 12 months. In the remaining 5 patients, the observation period was too short for outcome analysis.

In total, 23 patients received a rituximab-based regimen at a dosage of 375 mg/m2 intravenously. Of these, 16 patients received at least 4 infusions of 375 mg/m2 at weekly intervals (2 subjects received 6 and 8 cycles, respectively). In 2 other patients, intervals were expanded to 2-4 weeks. In 4 patients, rituximab was given together with Cytoxan, hydroxyrubicin, Oncovin, prednisone (CHOP)–based chemotherapy at 4-7 three-week intervals. One patient received only one cycle of rituximab. This patient who had presented critically ill died a few days after the first course of rituximab. Death was not considered to be related to rituximab but to the underlying MCD. No patient received a maintenance therapy with rituximab.

Rituximab infusions were generally well tolerated. There was only one patient with a presumed infusion-related reaction with fever and chills immediately after the fourth cycle. No new AIDS-defining illnesses occurred in any patient. However, there were 2 patients with an exacerbation of preexisting cutaneous KS lesions (1 patient developed new cutaneous lesions, and 1 patient presented with new visceral lesions in the stomach and gut). In both cases, KS lesions resolved at least partially after chemotherapy was started. Two further patients presented with a herpes zoster episode during the first year after rituximab.

With respect to immunologic and virologic control, the median CD4 T cells increased from 271-442 cells/μL at 9-12 months after administration of rituximab. There was only one patient who showed a significant decline of his CD4 T cells from 250 to 147 cells/μL at 12 months. Except for 4 patients who showed transient and low levels of HIV plasma viremia (“blips”) during the first year after rituximab, in all patients plasma HIV RNA remained below the limit of detection. No true virologic failure or resistance occurred.

In patients receiving C + R or R alone, the rates of a sustained complete remission were significantly higher than in patients receiving C(+ V) only (10 of 11 = 91% vs 9 of 22 = 41%, P < .01). This difference remained significant when second-line treatments were included in the analysis (13 of 15 vs 11 of 25, P = .01). In patients receiving R monotherapy, 7 of 8 (88%) and 9 of 11 (82%) achieved a sustained complete remission after first-line or after first- and/or second-line treatment, respectively. Of the 5 patients for whom the observation period was too short for analysis, 4 had received R only and one had received rituximab in combination with cytostatic therapy (R + C) + V. All were in complete (but not yet in sustained) remission. In contrast to rituximab-based regimens, the response rates in patients receiving antiviral agents were low. Only 4 of 12 (33%) patients receiving V only or a combination of C + V achieved a complete sustained remission.

After a mean follow-up of 2.26 years, 19 (40%) deaths have occurred. Mean estimated OS of the whole cohort was 6.2 years. Potential risk factors, such as older age, previous AIDS-defining events, and/or previous KS or lower CD4 T-cell counts, had no impact on OS. No predictive value was also found for lactate dehydrogenase, hemoglobin, or thrombocyte levels. Malignant lymphomas occurred in 5 patients at 0.1-5.5 years after MCD diagnosis. The subtypes were 3 plasmablastic lymphoma (a very rare diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, including one case with progression to plasmablastic leukemia), one anaplastic large B-cell lymphoma, and one primary effusion lymphoma. None of the patients had received rituximab for MCD before lymphoma diagnosis; 4 had received cytostatic therapy. Four of the 5 patients died because of lymphoma shortly after the diagnosis of the malignant disease.

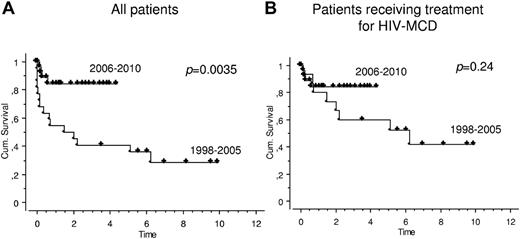

OS improved markedly since 2006 (Figure 1A). The mean estimated OS in the years 1998-2005 was 1.5 years versus not reached in the years 2006-2010 (P = .0035). However, this was mainly because, during 1998-2005, fewer patients had received a cytotoxic, antiviral, or immune-modulating treatment for HIV-MCD than during 2006-2010. When only patients receiving at least one HIV-MCD treatment were included in the analysis, there was only a trend (P = .24) toward a better OS during recent years (Figure 1B).

OS in patients with HIV-associated MCD. Kaplan-Meier survival statistics were used to evaluate OS in all 52 patients with HIV-MCD (A) and in those 47 patients who received treatment for HIV-MCD (B). OS was defined as the period from HIV-MCD diagnosis to death from any cause or the last contact (which was censored). During the study period (1998-2010), OS improved markedly since 2006. The mean estimated OS in the years 1998 to 2005 was 1.5 years versus not reached in the years 2006 to 2010 (P = .0035, panel A). When only patients receiving at least 1 HIV-MCD treatment were included, there was only a trend (P = .24) toward a better OS during recent years (panel B).

OS in patients with HIV-associated MCD. Kaplan-Meier survival statistics were used to evaluate OS in all 52 patients with HIV-MCD (A) and in those 47 patients who received treatment for HIV-MCD (B). OS was defined as the period from HIV-MCD diagnosis to death from any cause or the last contact (which was censored). During the study period (1998-2010), OS improved markedly since 2006. The mean estimated OS in the years 1998 to 2005 was 1.5 years versus not reached in the years 2006 to 2010 (P = .0035, panel A). When only patients receiving at least 1 HIV-MCD treatment were included, there was only a trend (P = .24) toward a better OS during recent years (panel B).

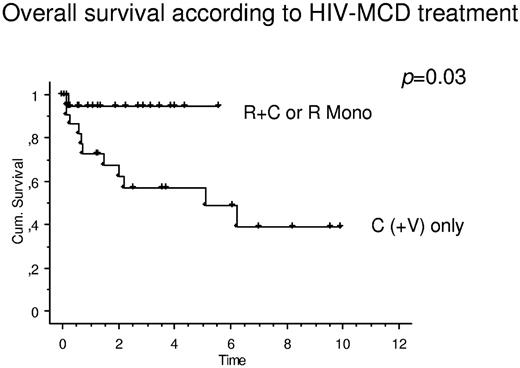

There were marked differences in OS when patients were grouped according to MCD treatment. When patients receiving rituximab only or in combination with cytostatic therapy were compared with patients receiving cytostatic therapy (with or without antiviral agents), there was a significant effect on OS toward rituximab-based regimens (Figure 2). The mean estimated OS of patients with R or R + C was not reached, compared with 5.1 years (P = .03) in patients receiving C(+ V).

OS in patients with HIV-associated MCD stratified according to MCD treatment. When patients receiving rituximab only (R Mono) or receiving R + C were compared with patients receiving cytostatic therapy (with or without antiviral agents; C(+V) only), there was a significant effect on OS toward rituximab-based regimens. The mean estimated OS of patients with R or R + C was not reached, compared with 5.1 years (P = .03) in patients receiving C(+V).

OS in patients with HIV-associated MCD stratified according to MCD treatment. When patients receiving rituximab only (R Mono) or receiving R + C were compared with patients receiving cytostatic therapy (with or without antiviral agents; C(+V) only), there was a significant effect on OS toward rituximab-based regimens. The mean estimated OS of patients with R or R + C was not reached, compared with 5.1 years (P = .03) in patients receiving C(+V).

Discussion

In this large cohort of HIV-infected patients with MCD, prognosis has markedly improved during recent years. This was mainly because, during the first years of the last decade, fewer patients had received an antiviral, cytostatic, or immune-modulating treatment for HIV-MCD. These results emphasize the importance of an effective treatment of HIV-MCD. When the analysis was restricted to patients receiving rituximab and/or cytostatic or antiviral agents for HIV-MCD, there was only a trend toward a better OS during recent years. Baseline factors, such as age, prior AIDS defining events, degree of the underlying immune deficiency, or hematologic parameters, were not found to be predictive for OS in our cohort. Of note, 80% of the patients had received prior antiretroviral therapy and many had reached a nondetectable plasma viral load, suggesting that the protective effect of ART is limited in HIV-MCD, in contrast to KS or malignant lymphomas.

With regard to HIV-MCD treatment, site-specific treatment preferences have led to considerable heterogeneity in this cohort. However, when patients receiving rituximab alone or in combination with cytostatic therapy were compared with patients receiving cytostatic therapy only, there was a significant effect toward rituximab-based regimens. With these regimens, more patients achieved a sustained complete remission, and OS was significantly improved.

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody against CD20-expressing cells. Although HHV-8–infected plasmablasts frequently do not express high levels of CD20, it has been speculated that rituximab is effective in HIV-MCD by eliminating or reducing the pool of HHV-8–infected B cells, which are localized mainly in the mantle zone of lymph nodes. After initial case reports,15-18 two recent pilot studies have evaluated rituximab in patients with HIV-MCD. In a French study,19 16 of 24 patients reached a complete remission of clinical symptoms after 4 cycles. The OS after one year was 92%. In a British study,20,21 20 of 21 patients achieved a clinical remission, and after 2 years, OS and disease-free survival were 95% and 79%, respectively. C-reactive protein, HHV-8 viremia, and cytokine levels decreased after treatment with rituximab.

Our results add important evidence to these studies. To our knowledge, the study presented here is the first to compare the benefits of different therapy modalities for HIV-MCD. Patients receiving rituximab-based regimens had higher remission rates and a better outcome than patients receiving chemotherapy only. However, there was at least 1 patient who clearly failed to respond during first-line treatment with rituximab. It can be speculated that treatment started too late in this individual case. Indeed, there are a few cases in the literature22,23 describing fulminant courses of HIV-MCD in which rituximab failed.

Despite these individual cases, we would consider rituximab-based therapies (with or without cytostatic agents) to be among the preferred first-line options in patients with HIV-MCD. The main adverse event of rituximab seems to be a reactivation of KS, which was seen in up to one-third of the cases in one of the 2 pilot trials.20 In our cohort, only 2 of 23 patients receiving rituximab-based therapies developed a KS reactivation. We observed no new AIDS-defining illnesses, no interference with virologic control, and no immunologic response to antiretroviral treatment. Of note, none of the 5 lymphomas observed in our cohort occurred in patients who had previously received rituximab. Thus, the relatively low incidence of lymphoma in our cohort, which seems to be lower than seen in earlier studies,3 could be an effect of both rituximab and an increased use of antiretroviral therapy.

We could not confirm the results of another pilot trial,24 in which 12 of 14 patients had shown a major clinical improvement after the first cycle of valgancyclovir (combined with high-dose zidovudine). As shown by a randomized trial,25 valgancyclovir significantly reduces the frequency and quantity of HHV-8 replication. Whether the lack of any effect was the result of the absence of higher zidovudine doses in our patients remains unclear. In line with some case reports,26,27 antiviral therapy with foscarnet or cidofovir alone had no benefit in our patients. We think that these two agents should no longer be used as the treatment of HIV-MCD.

Unambiguously, there are important limitations of this study, mainly because of its uncontrolled nature. First, there was a considerable heterogeneity in HIV-MCD treatment, which was primarily the result of the long time period of observation but was also driven by site-specific treatment preferences. This was also the case for the diagnostic procedures evaluating the treatment responses. Second, a possible bias through confounding by indication resulting from association between patient's pretreatment condition and physician's treatment decision cannot be ruled out. Current treatment protocols for HIV-MCD increasingly stratify therapy according to performance status and organ involvement.9 Performance status was not available in most patients. However, patients receiving rituximab only or rituximab in combination with cytostatic therapy had no significant differences in baseline characteristics compared with patients receiving cytostatic therapy only (data not shown). Third, a lead-time bias resulting from an earlier diagnosis by the pathologists and the treating physicians may have contributed to the improved outcome during recent years. Indeed, the time period between the first clinical symptoms and the diagnosis of HIV-MCD was remarkable in many patients, reaching up to 5 years. Although there was no difference between the time periods or patient groups regarding the time period between manifestation and diagnosis, the exact determination of the time of the first occurrence of HIV-MCD was difficult, given the overlapping clinical features of MCD and uncontrolled HIV infection. Fourth, in most patients, data on HHV-8 plasma viremia or cytokine levels, which has been proposed as a tool to monitor treatment response in patients with HIV-MCD,21,28 were not available.

Although we could show that rituximab plays a significant role in the treatment of HIV-MCD, some patients achieved a complete and sustained remission of HIV-MCD without rituximab. However, it remains unclear which patients benefit from these strategies and which patients do not. Likewise, the role of maintenance therapies, such as valgancyclovir, remains unclear. Given the rarity of the disease, a multinational collaboration to further elucidate these questions is needed.

Presented in part at the 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA, February 27 to March 2, 2011.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.H., M.M., and H.S. conceived and designed the study and collected and assembled the data; C.H., H.S., M.M., and K.A. analyzed and interpreted data; C.H. and K.A. wrote the manuscript; and all authors provided study materials or patients, had access to the primary clinical data, and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christian Hoffmann, Infektionsmedizinisches Centrum Hamburg, ICH Mitte, Dammtorstrasse 27, 20354 Hamburg, Germany; e-mail: hoffmann@ich-hamburg.de.

References

Author notes

C.H. and H.S. contributed equally to this study and should be regarded as first authors.