Abstract

The “in situ” lymphomas are often incidental findings in an otherwise reactive-appearing lymph node. Notably, the risk of progression to clinically appreciable lymphoma is not yet fully known. The diagnosis of “in situ” lymphoma is feasible when immunohistochemical characterization is carried out and genetic abnormalities are assessed. “In situ” follicular lymphoma is characterized by the presence within the affected germinal centers of B cells that strongly express BCL2 protein, a finding that supports their neoplastic nature, in the absence of interfollicular infiltration. In “in situ” mantle cell lymphoma, the lymphoma involvement is typically limited to the inner mantle zone, where lymphoma cells are cyclin D1+ and weakly BCL2+, CD5+. A staging workup to exclude other site of involvement is highly recommended for the possible coexistence of an overt lymphoma. Biopsy of all sites of suspicious involvement should be mandatory. No evidence for starting therapy also in the presence of multifocal “in situ” lymphoma exists, and a “wait-and-see policy” is strongly suggested. A follow-up strategy reserving imaging evaluation only in the presence of disease-related symptoms or organ involvement appears to be a reasonable option. For patients with concomitant overt lymphoma, staging and treatment procedures must be done according to malignant counterpart.

Introduction

Pathologists dealing with diagnostics of lymphomas, through the use of conventional methods and advanced technologies, on several occasions happen to come up against morphologic lesions that can presently be defined as “in situ” lymphomas.1 In these lesions, the neoplastic cells proliferate “in situ” (ie, in the “place” that is occupied by the normal counterpart of the tumor cell, without invasion of surrounding structures). For example, in the case of “in situ” follicular lymphoma (FL), the accumulation of neoplastic cells is within the lymphoid follicles only. For these reasons, “in situ” lymphoma does not usually form a tumor; rather, the lesion follows the existing architecture of the involved lymphoid follicles of the lymph node or the lymphoid tissue. On such occasions, the pathologist could be reluctant to make a diagnosis of lymphoma because he or she probably would not be able, today, to answer the questions about the clinical meaning of “in situ” lymphoma. Both the pathologist and the clinician, indeed, could hardly answer the patients' direct/indirect questions: should I worry about it? If so, how worried should I be?

The 2008 WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues has addressed the problem of “in situ” lesions among the early events in the evolution of lymphoid neoplasia.2-4 “In situ” lesions have been recognized for both FL and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). These “in situ” lesions are often incidental findings in an otherwise reactive-appearing lymph node, but the risk of progression to clinically appreciable lymphoma is not yet fully known for these focal lesions.1 Therefore, it is not surprising that clear guidelines for diagnosis and management of these patients are still lacking.

Given these considerations, in this paper we address this important and difficult topic that is increasingly recognized in the routine clinical practice. We discuss how to make a reliable and precise diagnosis of “in situ” lymphoma and when and how to treat the patient. The partnership between the pathologist and the clinician is crucial in the management of patients with these lesions that appear to have limited potential for histologic or clinical progression and for which clinical and therapeutic data are very limited.

“In situ” lymphomas among the early events in the evolution of lymphoid neoplasia

The concept of “in situ” lymphoma in this paper is used under the basic idea that considers as “in situ” lesions tumor cells that proliferate in the place that is occupied by the normal counterpart of the tumor cells without invasion of surrounding structures (“Introduction”). “In situ” FL and MCL can fulfill this idea. On the contrary, lymphomas that may regress when the initial stimulus is eliminated (early gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues lymphoma)5,6 or tumor that remains localized for a long period of time (duodenal FL)2 should not be included in the concept of “in situ” lymphoma.

Other early events with low risk of progression in the evolution of lymphoid neoplasia, as recognized by the 2008 WHO classification, include clonal expansions of B cells or, less often, T cells.7 Additional “in situ” lesions, which have been sporadically reported in the literature, are represented by 2 γ-herpesviruses associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders,8 termed plasmablastic microlymphoma9,10 and germinotropic lymphoproliferative disorder,11,12 respectively. However, the inclusion of these early lesions in the evolution of lymphoid neoplasia in the concept of “in situ” lymphoma may be controversial because they do not fulfill the main characteristic of these lesions (ie, the “in situ” location or proliferation). Moreover, on rare occasions, in HIV-infected patients, Epstein-Barr virus-associated Burkitt lymphoma may selectively involve the germinal centers (GCs) of lymph nodes or lymphoid tissues of the intestinal tract.13 A true follicular pattern similar to that seen in FL may occur. However, this is not an early event with low risk of progression because this “in situ” follicular location of BL is usually associated with synchronous aggressive lymphoma.13

“In situ” lymphoma is related to a distinct step in the molecular pathogenesis leading to overt lymphoma

Intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” FL

In some cases, “in situ” FL may be diagnosed as an isolated histopathologic finding. The process can remain benign; whereas, in some cases, “in situ” FL may be associated or may precede overt either FL or other lymphomas (Table 1). It seems probable that each of these clinical conditions is related to different steps in the molecular pathogenesis leading to FL.

“In situ” FL was originally described14 as being one of the early events associated with FL development. The t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation is the genetic hallmark and early initiating event of FL pathogenesis. This translocation is also present at low frequency in the peripheral blood of healthy persons where it is carried by circulating memory B cells and its oncogenic potential would be kept under control.15 The presence of the identical gene rearrangement within the lymph node and the peripheral blood in one recently observed case, however, is more in keeping with the hypothesis that these conditions represent potentially sequential steps in the molecular and cellular pathogenesis leading to FL.16,17 Although t(14;18) and ectopic BCL2 expression constitute the initial events of FL pathogenesis, additional events are clearly required for full malignant transformation.

“In situ” MCL

MCL is genetically characterized by the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation that juxtaposes the proto-oncogene CCND1, which encodes cyclin D1, at chromosome 11q13, to the Ig heavy chain gene at chromosome 14q32. As a consequence of the translocation, cyclin D1, which is not expressed in normal B lymphocytes, becomes constitutively overexpressed. The t(11;14) translocation is the primary event facilitating the transformation of a B lymphocyte that would initially colonize and expand the mantle cell area of the lymphoid follicles as seen in “in situ” MCL.18 The presence of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) or cell cycle checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) inactivating mutations may facilitate the development of the tumor. The mechanisms leading to the progression from this early proliferation to tumors with classic morphology are not well understood. However, the acquired alterations in the DNA damage response pathway may facilitate this process by increasing genomic instability.19

How to diagnose “in situ” lymphoma: microscopic examination

“In situ” FL and MCL are often discovered incidentally on a biopsy, performed for unexplained lymphadenopathy or for another reason, in which the lymph node shows diffuse hyperplasia or atypical follicular hyperplasia. In these cases, microscopic examination reveals follicular hyperplasia with conspicuous GCs surrounded by an apparently normal or mildly expanded mantle zone. The inclusion of BCL2, CD10, and cyclin D1 antibodies in the diagnostic panel can reveal isolated scattered follicles that are colonized by B cells overexpressing BCL2 and CD10, in the case of FL, or by B cells expressing CD5 and cyclin D1, in the case of MCL. Rarely, these “in situ” lesions may be discovered in lymph nodes involved by a lymphoproliferative unrelated process or by a metastatic nonlymphoid malignancy. The frequency with which “in situ” lymphomas occur is presently unknown; however, as an example, in the first report describing “in situ” localization of FL, the lesion was discovered in 2.5% (23 among 900) of lymph nodes received for consultation with a diagnosis of follicular hyperplasia.14

Intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” FL: diagnostic criteria

According to the typical scenario, the involved lymph node usually shows preservation of the nodal architecture with open sinuses and preserved paracortical regions. The lymph node predominantly contains lymphoid follicles with preserved mantle zones and GCs, whereas a few follicles may contain a monotonous population of small lymphoid cells. Therefore, on conventional stained sections, most follicles are cytologically reactive, whereas rare GCs appear to be monotonous in appearance and lack tingible body macrophages. On the basis of these morphologic findings, the diagnosis of “in situ” lymphoma is not feasible.

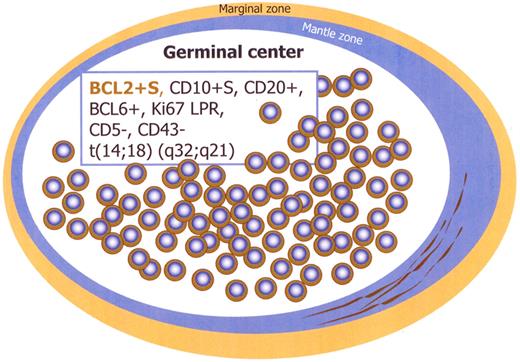

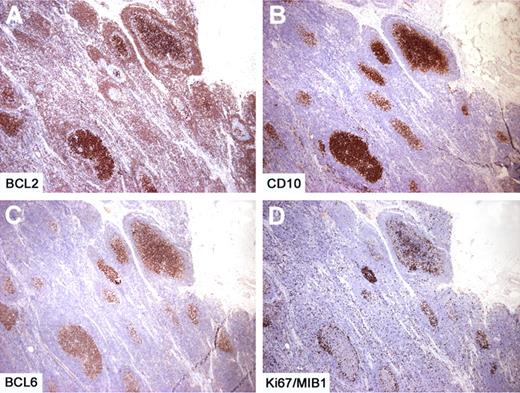

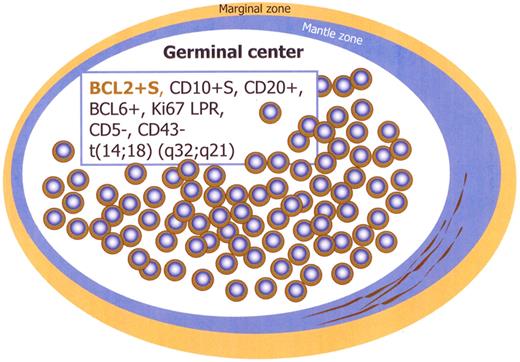

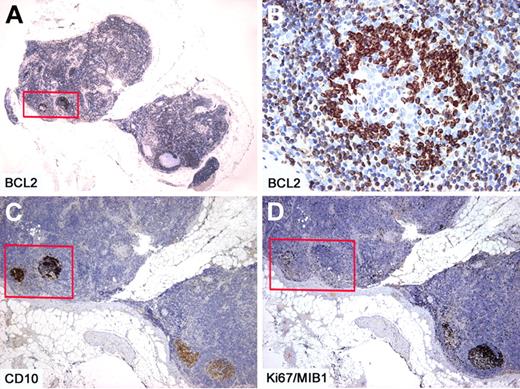

Immunohistochemistry studies show that the majority of follicles are negative for BCL2, whereas the few follicles with monotonous small cells in the same lymph node show strongly positive staining for BCL2 and CD10 (Figures 1,Figure 2–3). These follicles are CD20 and BCL6 positive but have a lower proliferation rate with ki67/MIB1, compared with the remaining reactive GCs in the same lymph node (Figures 2–3). The BCL2+ cells are confined only to GCs and are not seen in the interfollicular region or elsewhere in the lymph node (Figures 2–3).14,16,20-24 There is also a spectrum in the number of the BCL2-positive cells identified within affected follicles (Figure 3). Some of the involved GCs contain only a few positive cells in a background of BCL2-negative GC cells, whereas others are more extensively replaced by BCL2+ cells (Figure 3). The BCL2 staining in the abnormal follicles is notable for its high-level and uniform intensity. The intensity is much higher than that of admixed T lymphocytes or mantle zone cells, which usually show a weaker level of expression (Figure 2).

Immunophenotype of intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” FL (box). Schematic figure. S indicates strong; and LPR, low proliferation rate.

Immunophenotype of intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” FL (box). Schematic figure. S indicates strong; and LPR, low proliferation rate.

Intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” follicular lymphoma. Within 2 affected follicles (box), the BCL2+ (A-B) and CD10+ (C) cells are confined only to the GCs. Within the same affected follicles, the proliferation rate as assessed by Ki67/MIB1 is lower than that observed in reactive follicles (box) (D). Immunoperoxidase, hematoxylin counterstain. Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon) with Plan UW 2×/0.06 (A), Plan Fluor 20×/0.50 (B), Pan Fluor 4×/0.13 (C-D) objectives and Nikon digital sight DS-Fi1 camera equipped with control unit-DS-L2 (Nikon). Images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop 6 (Adobe Systems).

Intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” follicular lymphoma. Within 2 affected follicles (box), the BCL2+ (A-B) and CD10+ (C) cells are confined only to the GCs. Within the same affected follicles, the proliferation rate as assessed by Ki67/MIB1 is lower than that observed in reactive follicles (box) (D). Immunoperoxidase, hematoxylin counterstain. Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon) with Plan UW 2×/0.06 (A), Plan Fluor 20×/0.50 (B), Pan Fluor 4×/0.13 (C-D) objectives and Nikon digital sight DS-Fi1 camera equipped with control unit-DS-L2 (Nikon). Images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop 6 (Adobe Systems).

Intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” follicular lymphoma. In another case with several affected follicles, the number of BCL2+ cells is variable, whereas the BCL2 staining is consistently high and uniform (A). The proliferation is limited to the follicular areas, as demonstrated by CD10 (B) and BCL6 (C) and the proliferation rate is low (D). Immunoperoxidase, hematoxylin counterstain. Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon) with a Pan Fluor 4×/0.13 objective and Nikon digital sight DS-Fi1 camera equipped with control unit-DS-L2 (Nikon). Images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop 6 (Adobe Systems).

Intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” follicular lymphoma. In another case with several affected follicles, the number of BCL2+ cells is variable, whereas the BCL2 staining is consistently high and uniform (A). The proliferation is limited to the follicular areas, as demonstrated by CD10 (B) and BCL6 (C) and the proliferation rate is low (D). Immunoperoxidase, hematoxylin counterstain. Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon) with a Pan Fluor 4×/0.13 objective and Nikon digital sight DS-Fi1 camera equipped with control unit-DS-L2 (Nikon). Images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop 6 (Adobe Systems).

“In situ” MCL: diagnostic criteria

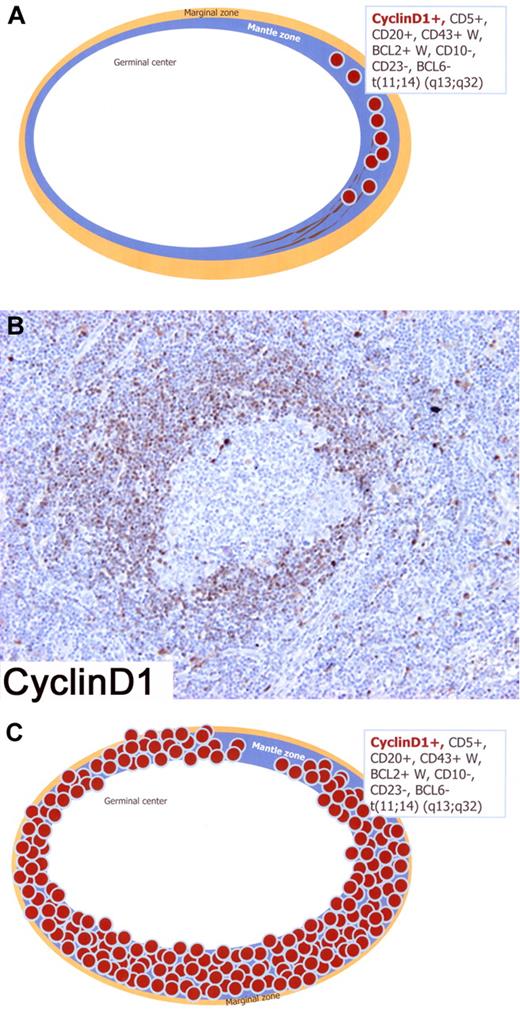

The earliest involvement of MCL is limited to the primary follicles or the inner mantle zones of secondary follicles with minimal or no expansion of these structures.25 In such cases, termed “in situ” MCL (Figure 4A), the neoplastic mantle zone is very thin and there is very little or no spread of tumor cells into interfollicular areas.26-30 Morphologically, GCs are hyperplastic with a normal or discretely enlarged mantle zone, where foci of cyclin D1+, CD5+, and CD20+ tumor cells are seen by immunohistochemistry studies (Figure 4A).26

Schematic figure of “in situ” mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and early involvement of overt MCL; immunophenotype in the box. (A) Schematic figure of “in situ” MCL in which lymphoma cells are restricted to the inner zone of the mantle, pattern A (“in situ” MCL). (B) Lymphoma involvement is limited to the mantle zone of a secondary follicle with minimal expansion of this structure. Only a fraction of mantle cells expresses Cyclin D1, pattern B (“in situ” MCL?). (C) Schematic figure of early involvement of overt MCL showing that the lymphoma cells completely involve the expanded mantle zone of the follicle, pattern C (overt MCL). Immunoperoxidase, hematoxylin counterstain. (B) Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon) with a Plan Fluor 20×/0.50 objective and Nikon digital sight DS-Fi1 camera equipped with control unit-DS-L2 (Nikon). Images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop 6 (Adobe Systems).

Schematic figure of “in situ” mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and early involvement of overt MCL; immunophenotype in the box. (A) Schematic figure of “in situ” MCL in which lymphoma cells are restricted to the inner zone of the mantle, pattern A (“in situ” MCL). (B) Lymphoma involvement is limited to the mantle zone of a secondary follicle with minimal expansion of this structure. Only a fraction of mantle cells expresses Cyclin D1, pattern B (“in situ” MCL?). (C) Schematic figure of early involvement of overt MCL showing that the lymphoma cells completely involve the expanded mantle zone of the follicle, pattern C (overt MCL). Immunoperoxidase, hematoxylin counterstain. (B) Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon) with a Plan Fluor 20×/0.50 objective and Nikon digital sight DS-Fi1 camera equipped with control unit-DS-L2 (Nikon). Images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop 6 (Adobe Systems).

It is possible that MCL is initially CD5−, and CD5 expression follows acquisition of additional genetic lesions and evolution to overt MCL. CD5−, cyclin D1+, and t(11;14)+ MCLs resembling other small B-cell lymphomas, such as marginal zone lymphoma or FL, have been described. These probably represent a divergent evolutionary pathway, possibly dictated by a different set of secondary events distinct from those seen in overt MCL.25,31

Patients with “in situ” MCL need proper evaluation to exclude the coexistence of overt MCL. In the absence of coexisting overt MCL, the clinical impact of the diagnosis is doubtful and close follow-up is essential.25

Criteria for the distinction between “in situ” FL or MCL and “early” involvement of overt lymphoma

The challenge is to distinguish the true “in situ” lymphoma cases from lymph nodes with “early” involvement of overt FL or MCL.

In “in situ” FL, the BCL2-positive, strongly stained cells are confined only to GCs and are not seen in the interfollicular regions or elsewhere in the lymph node, where they produce an exclusively intrafollicular growth pattern. Furthermore, the “in situ” FL involvement occurs within selected GCs in otherwise reactive lymph node. On the contrary, in overt FL, even in the early phase of lymph node involvement, infiltration of the interfollicular regions and involvement of many or most of the follicles are usual. According to these criteria, it may be possible to distinguish cases of “in situ” FL (with follicular colonization of few reactive follicles; ie, true “in situ” FL), from early involvement by overt FL with some spared reactive follicles (ie, overt FL with partial lymph node involvement). In other words, “in situ” FL is a condition in which the overwhelming majority of the follicles is reactive, whereas in overt FL with preserved reactive GCs, many or most of the follicles are involved by FL.7,32,33

In “in situ” MCL, the lymphoma cells are almost exclusively restricted to the inner mantle zone or to narrow mantles (pattern A in Figure 4A). In overt MCL, lymphoma cells in the lymph nodes adopt a mantle zone, nodular, or diffuse growth pattern, which might represent different stages of tumor infiltration. In early involvement of overt MCL, lymphoma cells substitute the mantle zone and tend to invade the reactive GC. This mantle zone growth pattern is characterized by an expansion of the follicle mantle area by neoplastic cells surrounding reactive GCs (pattern C in Figure 4C). However, in cases with features intermediate between these distinct patterns (pattern B in Figure 4B), it is certainly difficult to draw a definite line between “in situ” MCL and early involvement of overt MCL showing a mantle zone pattern. Notably, this latter pattern (pattern B) is usually seen in areas of partially involved lymph nodes that otherwise show involvement by an overt MCL.

How to diagnose “in situ” lymphoma: clinical characteristics

Clinical presentation

Data on clinical presentation of “in situ” lymphomas are very limited with only a few papers reporting very small series or case reports.14,16,20,25,26

By consequence, no definitive suggestions on the conventional management of these patients can be given. Nonetheless, clinicians are sometimes involved in managing patients with such diagnosis as performed by pathologist. Obviously, this diagnosis may cause an important psychologic distress in otherwise healthy persons, although its malignant potential is unclear. The lack of a well-defined clinical flow-chart could increase the distress.

In this section we provide practical suggestions on the management of these patients which, based on the limited reported series as well as on the clinical experience in the counterpart lymphoma, could help physicians in everyday clinical practice.

“In situ” FL is the more frequent histotype. Its main clinical characteristics are represented by the high incidence (overall ∼ 50%) of synchronous or metachronous FL, suggesting homing to an early colonization of reactive GCs by FL.14,20 However, a high incidence of other non-FL lymphoid neoplasia may suggest that “in situ” lymphoma may be a sign of an increased tendency to develop lymphoid malignancies because of underlying molecular abnormalities.14,20 Furthermore, the remaining cases do not seem to develop lymphoma along the follow-up period, and strongly support the hypothesis of an earliest stage of development of FL, as well as of a preneoplastic event, requiring a second hit for neoplastic transformation.14

Cases of “in situ” MCL are anecdotal25,26 with some difficulties in distinguishing between MCL with a nodular pattern and real “in situ” MCL.25 Nonetheless, the patterns of presentation as well as of evolution seem to be more strictly related to the counterpart MCL with a more extensive presentation and a more aggressive behavior.

Staging workup

Determination of disease extent by staging workup is of major concern in malignant lymphoma providing pretreatment risk assessment, adequate treatment planning, and appropriate evaluation of therapeutic results.34-36

Several staging systems and prognostic scores have been proposed and are worldwide accepted for the different lymphoma histotypes35,36 However, the staging procedures for “in situ” lymphoma are not defined, and a proposal can be only speculative in the absence of clear guidelines. By principle, all patients with “in situ” lymphoma should proceed to an accurate workup (Table 2) because of the concomitant possible overt disease. Actually, some staging procedures, like physical examination, blood tests, flow cytometry, CT scan with intravenous contrast of neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, should be done in all “in situ” lymphomas.

In patients with “in situ” lymphoma presenting with flow cytometry abnormalities and additional nodal or extranodal enlargement, unilateral bone marrow biopsy and biopsy of one or more sites of suspicious involvement are mandatory to exclude the synchronous overt lymphoma. Furthermore, other specific investigations, such as PET scan, gastroscopy, colonoscopy, gastric endosonography, and molecular and cytogenetic studies, on blood or bone marrow should be performed only in the presence of specific symptoms or whenever a concomitant diagnosis of overt lymphoma has been done.

A matter of debate in classifying patients with concomitant “in situ” and overt lymphoma could be how to consider the “in situ” nodal involvement according to staging systems and/or prognostic scores. Once again, clear rules are lacking; nonetheless, it seems advisable to consider such “in situ” localizations as involved areas due their potential evolution in overt lymphoma.14,20

Response criteria

For patients with overt lymphoma, synchronous or metachronous to “in situ” lymphoma, criteria for response are similar to those reported for the malignant lymphomas according to histology and localization.34-36

In patients without overt lymphoma, thus not receiving therapy, only disease progression should be assessed.

How to treat or not to treat “in situ” lymphoma

The treatment approach for “in situ” lymphoma is profoundly influenced by the concomitant coexistence or not of an overt lymphoma (Table 1).

For patients without evidence of overt lymphoma, a “wait-and-see policy” is strongly suggested, especially in “in situ” FL. A follow-up strategy reserving imaging evaluation only in the presence of disease-related symptoms or organ involvement appears a valid option. This strategy applies also to patients with multiple sites of “in situ” involvement as well as circulating cells detected by flow cytometry, for whom no worse prognosis has been so far documented.

A more cautious attitude should be reserved to patients with “in situ” MCL. Actually, the more aggressive behavior of overt lymphoma counterpart could suggest a closer follow-up, even in the absence of evidence of higher aggressiveness of the “in situ” MCL entity.

By a general viewpoint, there are no indications to start treatment in “in situ” lymphoma patients, without clear evidence of concomitant or subsequent overt lymphoma.

In all cases of coexistence of both “in situ” and overt lymphoma, treatment must be started according to the histotype, stage, and localization of overt lymphoma, independently of the “in situ” histology. A matter of debate could be represented by the role of “in situ” involved site in defining stage and prognostic score as well as in treatment planning. In the absence of clinical and scientific evidence, considering the “in situ” site as involved appears to be reasonable.

Overlapping conclusions apply to patients developing overt lymphoma during follow-up. After a mandatory biopsy of nodal or extranodal involvement and staging, patients must be addressed to the standard approach in relation to histology, stage, and localization. Once again evaluation of initial site of “in situ” lymphoma could be advisable.

How to follow-up

For patients with overt lymphoma concomitant with or developing after “in situ” lymphoma, the follow-up evaluation should agree with the international guidelines34-36 according to histology and/or localization.

For those patients without overt lymphoma, a clinical follow-up, based mostly on careful history and symptoms, and physical examination, should be highly suggested, reserving imaging techniques in the suspect of disease-related symptoms or signs of organ involvement. However, the biopsy of new nodal or extranodal lesion, suspicious for lymphoma, is mandatory in all cases.

Particular concern should be reserved to the psychologic implications related to the communication of a disease of uncertain clinical behavior in otherwise healthy persons.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in epithelial tumors, the concept of “in situ” neoplasia is well established. One can extend the concept to lymphoid neoplasms when the bulk of the neoplastic cells are restricted to a particular area that is occupied by the normal counterpart of the tumor cell. It should be stressed that, in contrast to “in situ” epithelial cancers, minimal disease may extend beyond the boundaries of a particular compartment.25

Even if the lesion is usually limited from a quantitative viewpoint, the diagnosis of “in situ” lymphoma is feasible when immunohistochemical characterization is carried out and genetic abnormalities are assessed.24 The good quality of the tissue sample is unavoidable and is a “sine qua non” condition.

Intrafollicular neoplasia/“in situ” FL is characterized by the presence of GC B cells that strongly express BCL2 protein, a finding that supports their neoplastic nature, whereas the remaining lymph node shows a pattern of follicular hyperplasia in the absence of interfollicular infiltration. The earliest involvement of MCL is limited to the mantle zone of secondary follicles with no expansion of these structures. “In situ” MCL shows that, in contrast with the negative central reactive GCs, the inner mantle zone B cells are cyclin D1+ and weakly BCL2+, CD5+.

A staging workup to exclude other sites of nodal or extranodal involvement is highly recommended for the possible coexistence of an overt lymphoma. Biopsy of all sites of suspicious involvement should be mandatory. No evidence for starting therapy also in the presence of multifocal “in situ” lymphoma exists, and a “wait-and-see policy” is strongly suggested. A follow-up strategy reserving imaging evaluation only in the presence of disease-related symptoms or organ involvement appears to be a reasonable option. For patients with concomitant overt lymphoma, staging and treatment procedures must be done according to malignant counterpart.

Furthermore, in these rare clinical conditions, a continuous interchange between the pathologist and the clinician is needed to guarantee the best treatment options to the patient. The real challenge remains to unravel and understand the biologic features that will identify cases that are at risk of developing overt lymphoma.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annunziata Gloghini (Department of Diagnostic Molecular Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Fondazione Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Milano Italy) for the critical discussion on the concept of “in situ” lymphoma and the diagnostic criteria for the precise identification, and Elettra Gislon (Scientific Direction, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico Aviano, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Aviano, Italy) for the English revision of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the Ministero della Salute, Rome, within the framework of the Progetto Integrato Oncologia-Advanced Molecular Diagnostics project (RFPS-2006–2-339694).

Authorship

Contribution: A.C. and A.S. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Antonino Carbone, Division of Pathology, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico Aviano, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Via F. Gallini 2, 33081 Aviano, Italy; e-mail: acarbone@cro.it.