Abstract

During postnatal life, the bone marrow (BM) supports both self-renewal and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in specialized microenvironments termed stem cell niches. Cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions between HSCs and their niches are critical for the maintenance of HSC properties. Here, we analyzed the function of N-cadherin in the regulation of the proliferation and long-term repopulation activity of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) by the transduction of N-cadherin shRNA. Inhibition of N-cadherin expression accelerated cell division in vitro and reduced the lodgment of donor HSPCs to the endosteal surface, resulting in a significant reduction in long-term engraftment. Cotransduction of N-cadherin shRNA and a mutant N-cadherin that introduced the silent mutations to shRNA target sequences rescued the accelerated cell division and reconstitution phenotypes. In addition, the requirement of N-cadherin for HSPC engraftment appears to be niche specific, as shN-cad–transduced lineage−Sca-1+c-Kit+ cells successfully engrafted in spleen, which lacks an osteoblastic niche. These findings suggest that N-cad–mediated cell adhesion is functionally required for the establishment of hematopoiesis in the BM niche after BM transplantation.

Introduction

Interaction of tissue stem cells with their supportive microenvironment, the stem cell niche, is critical to sustaining the balance between self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells in tissues over long periods.1-5 More specifically, cell-cell and cell-extracellular interaction of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) with their niche components is necessary for lifelong maintenance of hematopoiesis. Indeed, transplanted HSCs have been shown to interact with osteoblastic and perivascular niches.6,7

Cadherins are cell adhesion molecules responsible for Ca2+-dependent cell-cell interaction, and they play pivotal roles in maintaining tissue architecture.8-10 The role of cadherin in the Drosophila germline stem cell niche has been well characterized.11,12 However, the expression and function of N-cad in mammalian HSCs have not been resolved. Kiel et al13 and Foudi et al14 reported that N-cad is not expressed in long-term (LT)–HSCs. In addition, it has been suggested that N-cad is not involved in HSC maintenance.15 In conflicting reports, N-cad expression has been reported in subpopulations of HSCs and osteoblasts in mouse and human.7,16-19 Haug et al proposed a model in which N-cad may act as a signal that triggers a subpopulation of HSCs to transit between “reserved” (dormant) and “primed” (active) states.18 Although it has been reported that N-cad shows both homophilic (N-cad/N-cad) and heterophilic interactions (N-cad/R-cad20,21 and N-cad/OB-cad22 ), single-cell real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis revealed that hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) specifically express N-cad and not several other cadherin genes (E-, N-, P-, R-, VE-, K-, OB-, BR-, M-cad, and Cdh7) at the single-cell level.19 Moreover, endosteal cell populations (mesenchymal progenitor cells, immature and mature osteoblastic cells) express a variety of cadherins to various degrees.19

In addition to the diverse reports regarding HSC N-cad expression, the function of N-cad in vivo also remains uncertain. Kiel et al15 reported that N-cad conditional knockout mice do not show HSC defects. In contrast, we recently demonstrated that inhibition of cadherin-mediated homophilic and heterophilic adhesion by the overexpression of dominant negative (DN)-N-cad reduced the long-term reconstitution (LTR) activity of HSPCs.19 In this study, we sought to determine whether N-cad is involved in the regulation of HSPC proliferation and engraftment by altering endogenous N-cad levels. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA)–mediated knockdown of N-cad expression in HSPCs accelerated cell division in vitro. Furthermore, transduction of N-cad shRNA reduced HSPC anchoring to the endosteal surface (lodgment) and significantly inhibited the long-term engraftment of HSPCs, specifically in the bone marrow (BM). These findings indicate that the inhibition of N-cad function may adversely affect the ability of HSPCs to home to and be retained in their BM niche and maintain their quiescence.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6-Ly5.2) and C57BL/6 mice congenic for the Ly5 locus (B6-Ly5.1) were purchased from Sankyo-Lab Service. Animal care was in accordance with the Guidelines of Keio University for Animal and Recombinant DNA experiments. All mouse experiments were approved by the animal ethics committee of Keio University.

Antibodies

The following monoclonal antibodies (Abs) were used for flow cytometry and cell sorting: anti–c-Kit (2B8; BD Biosciences), anti–Sca-1 (E13-161.7; BD Biosciences), anti-CD4 (L3T4; BD Biosciences), anti-CD8 (53-6.72; BD Biosciences), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2; BD Biosciences), anti–TER-119, anti–Gr-1 (RB6-8C5; BD Biosciences), and anti–Mac-1 (M1/70; BD Biosciences). A mixture of Abs directed against CD4, CD8, B220, TER-119, Mac-1, and Gr-1 was used as the lineage mix. The following Abs were used for Western blot analysis: MNCD2,23 rabbit anti–N-cad polyclonal Ab (pAb; Abcam), and mouse anti–N-cad monoclonal Ab (mAb; clone 32; BD Biosciences). Anti-GFP (Medical & Biological Laboratories), anti–β-catenin (clone 14; BD Biosciences), and anti-Lef1 (C12A5; Cell Signaling Technology) were used for immunohistochemical and immunocytochemical staining.

Cell preparation, flow cytometry, and immunocytochemistry

The procedures for cell preparation and immunohistochemical staining for flow cytometry were described previously.24 Stained cells were analyzed and sorted using a FACSvantage DiVa (BD Biosciences).

Sequences of N-cad shRNAs

Sequences of N-cad shRNAs were as follows: shN-cad-1, 5′-GGATGTGCACGAAGGACAG-3′; shN-cad-2, 5′-GCCACAGACATGGAAGGCA-3′.25 The sequence was separated by a 9-nucleotide noncomplementary spacer (TCTCTTGAA) from the corresponding reverse complement of the same 19-nucleotide sequence. A scrambled sequence (5′-GACACGCGACTTGTTGTACCAC-3′) served as a control.

Construction of N-cad shRNAs and lentiviral transduction

Oligonucleotides were first inserted into pSUPER (Oligoengine), and the EcoRI and ClaI fragment was then digested and cloned into the pLV-TH lentivirus vector. For transduction of the N-cad shRNAs, isolated lineage−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells or LSK-CD34− cells were precultured for 1 day, transfected with lentivirus-shN-cads on RetroNectin (Takara Bio) using Magnetofection (OZ Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and then cultured for 2 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. The culture was maintained in SF-O3 medium in the presence of 1.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 100 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF; PeproTech), and 100 ng/mL thrombopoietin (TPO; PeproTech).

Construction of retroviral vectors expressing shRNA-resistant N-cad and retroviral transduction

N-cad with silent mutations within the shRNA targeting sequences (silent mutant N-cad, sil.mut.N-cad) was ligated into pMY-IRES-monomeric Kusabira Orange (mKO). To transduce retroviruses into LSK cells, isolated Ly5.1+ LSK cells were precultured for 2 days, transfected on RetroNectin plates using Magnetofection, and then incubated for 2 days. The culture was maintained in SF-O3 medium containing 1.0% BSA, 100 ng/mL SCF, and 100 ng/mL TPO.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

LSK cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2. After 2 days of transduction, RNA was isolated from GFP+ cells (1 × 104 cells/sample) and reverse transcribed using an RT for PCR Kit (Clontech). Quantitative PCR was performed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan Fast Universal PCR master mixture (Applied Biosystems). LSK-CD34− cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2. After 2 days of transduction, Lin−GFP+ cells (1 × 103 cells) were sorted directly into the mixture of CellsDirect 2 × Reaction Mix (Invitrogen), 0.2 × TaqMan Gene Expression Assays, and SuperScript III RT/Platinum Taq Mix (Invitrogen). Procedures for the reverse-transcription, specific target amplification, and quantitative real-time PCR using nanofluidic array chips (BioMark 48·48 Dynamic Array; Fluidigm) were described previously.26 Data were analyzed using BioMark Real-Time PCR Analysis Software Version 2.1.1 (Fluidigm). The following TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Mixes (Applied Biosystems) were used for quantitative real-time PCR analysis: N-cad (Mm00483213_m1), R-cad (Mm00486932_m1), VE-cad (Mm00486938_m1), OB-cad (Mm00515462_m1), Actb (Mm00607939_s1), and Hprt1 (Mm00446968_m1).

Western blot

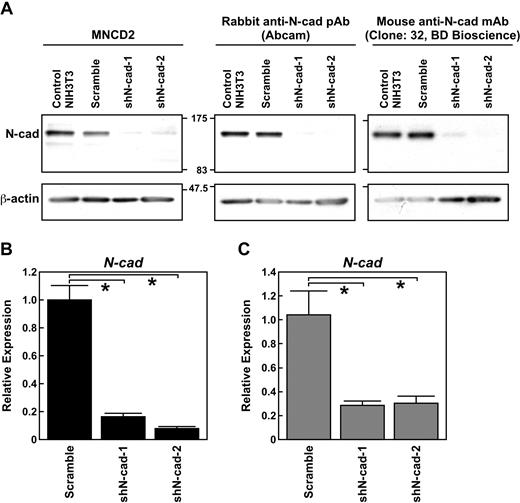

NIH3T3 cells were transduced with scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2, and gene-transduced cells (GFP+) were sorted and cultured for several passages. Levels of N-cad protein in NIH3T3 cells were examined by Western blot using MNCD2 (rat anti–mouse N-cad mAb), rabbit anti–N-cad pAb (Abcam), and mouse anti–N-cad mAb (Clone: 32; BD Biosciences).

Cell division assay

To analyze the effect of N-cad knockdown on cell division, LSK cells were cotransduced with lentiviruses expressing shN-cad-1 or -scramble and retroviruses expressing control-Kusabira Orange (KO) or sil.mut.N-cad. Single cells transduced with lentivirus and/or retrovirus vectors were cultured on control- or N-cad-Fc–coated plates in SF-O3 medium with 1.0% BSA, 100 ng/mL SCF, and 100 ng/mL TPO. The number of days required for a single cell to reach more than 30 cells was recorded. In addition, the number of cells in each colony was counted on day 7 of culture.

Cell-cycle analysis

For cell-cycle analyses, LSK cells were transduced with scramble-shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2, and then transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. Two weeks after BM transplantation (BMT), BM cells were collected from recipient mice and stained for LSK. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). The frequency of GFP+ LSK cells in G0/G1 and S/G2/M phase was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS).

Colony-forming assays

Scramble-shRNA–, shN-cad-1–, and shN-cad-2–transduced LSK cells were sorted and cultured in methylcellulose medium (Methocult GF M3434; StemCell Technologies). After 10 days, the number of colonies containing more than 50 cells were counted (colony-forming units in culture). To evaluate the number of high proliferative potential-colony forming cells, the number of colonies more than 0.5 mm in diameter was also determined.

Immunohistochemical and immunocytochemical staining

To analyze the function of N-cad in HSPC lodgment after BMT, LSK cells were transduced with shRNA and transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. After 36 hours, BM sections were prepared, and the localization of GFP+ donor cells was examined by immunohistochemical staining. Procedures for preparation and staining of BM sections have been previously described.24 For nuclear staining, specimens were treated with TOTO3 (Invitrogen). For immunocytochemical staining, cells were centrifuged onto microscope slides using a cytospin centrifuge (Shandon Southern Products), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100. After blocking, samples were incubated with primary Ab at 4°C overnight, washed with PBS, and stained with a fluorescence-labeled secondary antibody. Fluorescence images were obtained using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (FV1000; Olympus).

Homing and lodgment assays

Scramble-shRNA–, shN-cad-1–, and shN-cad-2–transduced cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. Mice were killed 36 hours later, and the percentage of GFP+ donor cells was determined in the BM and spleen. To evaluate the lodgment of transplanted cells, BM sections were prepared from mice 36 hours after BMT and stained with anti-GFP Ab as described in “Immunohistochemical staining.” The percentage of GFP+ cells adhering to the endosteal surface was determined by confocal laser scanning microscopy. For rescue experiments, retroviruses expressing control-mKO or sil.mut.N-cad were cotransduced with shN-cad-1 into LSK cells and transplanted into lethally irradiated mice.

BM reconstitution assay

To analyze the effect of N-cad knockdown on the LTR activity of HSPCs, LSK cells were isolated from Ly5.1 (CD45.1+) mouse BM, transduced with lentiviruses expressing scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2, and transplanted into lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy) recipient mice with 2.5 × 105 Ly5.2 BM mononuclear cells. The percentage of donor cells in the recipients' peripheral blood (PB) was analyzed 1 to 3 months after BMT. For rescue experiments, retroviruses expressing control-mKO or sil.mut.N-cad were cotransduced with shN-cad-1 into LSK cells. Gene-transduced LSK cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice together with 2.5 × 105 Ly5.2 BM mononuclear cells. The percentage of donor cells in the recipients' PB, mononuclear cells (MNCs), and LSK cells in the BM and spleen were analyzed 6 months after BMT.

Statistical analysis

Significant differences between groups were determined using a 2-tailed Student t test and Tukey test.

Results

N-cad knockdown in LSK cells

To determine whether N-cad expression was effectively suppressed by N-cad–specific shRNAs, we generated shN-cad-1 and -2 lentiviral vectors and introduced them into NIH3T3 cells. We confirmed that both N-cad shRNAs suppressed N-cad expression in NIH3T3 cells by Western blot with 3 independent anti–N-cad Abs (Figure 1A). We then sought to determine whether inhibition of N-cad was specific and effective in LSK cells. LSK cells were transduced with shN-cad-1 and -2. After 2 days, GFP+ cells were sorted, and the expression of N-, R-, VE-, and OB-cad mRNA was analyzed. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis showed that both N-cad shRNAs efficiently suppressed N-cad in LSK cells (Figure 1B) but did not alter R-, VE-, or OB-cad expression (data not shown). We previously reported that LT-HSCs (LSK-CD34− cells) highly expressed N-cad compared with short-term (ST)-HSCs (LSK-CD34+ cells).19 In this study, we confirmed that the transduction of shN-cad-1 and -2 suppressed N-cad expression in LSK-CD34− LT-HSCs (Figure 1C) but did not induce the expression of R-, VE-, and OB-cad (data not shown). We also performed immunocytochemical staining for N-cad in shN-cad– or scramble shRNA–transduced LSK-CD34− cells, and found that transduction of shN-cad-1 or -2 suppressed N-cad protein expression in LSK-CD34− cells (data not shown).

Efficiency of N-cad knockdown by shN-cad-1 and -2. (A) Western blotting revealed a reduction in N-cad protein abundance in NIH3T3 cells transfected with N-cad shRNAs but not with scramble shRNA. MNCD2, a rabbit anti–N-cad pAb (Abcam), and a mouse anti–N-cad mAb (clone 32, BD Biosciences) were used to detect N-cad protein. (B) Effects of shN-cad-1 and -2 on the expression of N-cad in LSK cells. After transduction of shN-cad-1 and -2, N-cad expression was analyzed. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that both shN-cad-1 and -2 significantly suppressed the expression of N-cad in LSK cells. Data are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .01. (C) Effects of shN-cad-1 and -2 on the expression of N-cad in LSK-CD34− cells (LT-HSCs). The expression of N-cad in shRNA-transduced cells was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using a nanofluidic chip. Data are mean ± SD; n = 5. *P < .01.

Efficiency of N-cad knockdown by shN-cad-1 and -2. (A) Western blotting revealed a reduction in N-cad protein abundance in NIH3T3 cells transfected with N-cad shRNAs but not with scramble shRNA. MNCD2, a rabbit anti–N-cad pAb (Abcam), and a mouse anti–N-cad mAb (clone 32, BD Biosciences) were used to detect N-cad protein. (B) Effects of shN-cad-1 and -2 on the expression of N-cad in LSK cells. After transduction of shN-cad-1 and -2, N-cad expression was analyzed. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that both shN-cad-1 and -2 significantly suppressed the expression of N-cad in LSK cells. Data are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .01. (C) Effects of shN-cad-1 and -2 on the expression of N-cad in LSK-CD34− cells (LT-HSCs). The expression of N-cad in shRNA-transduced cells was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using a nanofluidic chip. Data are mean ± SD; n = 5. *P < .01.

Function of N-cad in the regulation of HSPC division in vitro

N-cad expression has been reported to correlate with active and dormant HSC states.18 Consistent with these data, we previously found that the enhanced cell adhesion induced by N-cad overexpression resulted in slowed HSPC division because of altered β-catenin function and up-regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors.19 Therefore, we evaluated the effect of shRNA-mediated N-cad silencing on the cell division of HSPCs. To specifically rescue the N-cad knockdown, N-cad encoding silent mutations within the shRNA targeting sequence (silent mutant N-cad,sil.mut.N-cad; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) were cotransduced with shN-cad-1. The experimental scheme of the cell division assays is shown in Figure 2A. As expected from our previous work, sil.mut.N-cad (ie, N-cad overexpression) reduced the cell number in each colony (Figure 2B). Cotransduction of shN-cad-1 and control-mKO shortened the number of days required for a single cell to reach 30 cells or more, whereas the accelerated cell division induced by shN-cad was rescued by cotransduction with sil.mut.N-cad (Figure 2C). These data suggest that N-cad silencing accelerates cell division of HSPCs in vitro, and further indicate that the N-cad shRNAs specifically silenced N-cad in HSPCs.

Effects of shN-cads on HSPC cell division in vitro. (A) Cell division assay experimental scheme. LSK cells were cotransduced with lentiviruses expressing shN-cad-1 or -scramble and retroviruses expressing control-mKO or N-cad with a silencing mutation in the shRNA targeting sequence (sil.mut.N-cad). Gene-transduced LSK cells were clone-sorted onto control- or N-cad-Fc–coated plates and cultured in SF-O3 medium with 1.0% BSA, SCF, and TPO. The number of cells in each colony on day 7 (shown in B) and the days required for a single cell to reach more than 30 cells (shown in panel C) were analyzed. (B) The number of cells in each colony on control- and N-cad-Fc–coated plates at day 7 of culture. *P < .05. (C) The percentage of colonies with more than 30 cells per colony on each day of culture are shown. Transduction of N-cad shRNA into LSK cells reduced the number of days required for a single cell to reach 30 cells or more, whereas sil.mut.N-cad rescued the accelerated cell division induced by shN-cad-1. (D) Hoechst staining of GFP+ LSK cells 2 weeks after BMT. (E) The percentage of GFP+LSK cells in G0/G1. Data are mean ± SD. **P < .05.

Effects of shN-cads on HSPC cell division in vitro. (A) Cell division assay experimental scheme. LSK cells were cotransduced with lentiviruses expressing shN-cad-1 or -scramble and retroviruses expressing control-mKO or N-cad with a silencing mutation in the shRNA targeting sequence (sil.mut.N-cad). Gene-transduced LSK cells were clone-sorted onto control- or N-cad-Fc–coated plates and cultured in SF-O3 medium with 1.0% BSA, SCF, and TPO. The number of cells in each colony on day 7 (shown in B) and the days required for a single cell to reach more than 30 cells (shown in panel C) were analyzed. (B) The number of cells in each colony on control- and N-cad-Fc–coated plates at day 7 of culture. *P < .05. (C) The percentage of colonies with more than 30 cells per colony on each day of culture are shown. Transduction of N-cad shRNA into LSK cells reduced the number of days required for a single cell to reach 30 cells or more, whereas sil.mut.N-cad rescued the accelerated cell division induced by shN-cad-1. (D) Hoechst staining of GFP+ LSK cells 2 weeks after BMT. (E) The percentage of GFP+LSK cells in G0/G1. Data are mean ± SD. **P < .05.

The percentage of colonies consisting of less than 20 cells per colony was increased when sil.mut.N-cad–expressing cells were cultured on N-cad-Fc–coated plates (Figure 2B). In addition, N-cad-Fc–coated plates extended the period of days required for a single sil.mut.N-cad–expressing LSK cell to generate more than 30 cells (Figure 2C), indicating that an N-cad–mediated homophilic interaction inhibits HSPC division. However, because the cell number per colony was also slowed by sil.mut.N-cad in the absence of N-cad coating (Figure 2B-C), adhesion-independent mechanisms may also contribute to the N-cad–mediated slowing of HSPC division.

N-cad silencing accelerates the cell cycle of LSK cells after BMT

Because N-cad silencing altered cell division, we next analyzed the cell-cycle status of shN-cad–transduced LSK cells. Because LSK cells were stimulated to proliferate before lentiviral transduction, we analyzed the cell cycle of scramble-, shN-cad-1–, and shN-cad-2–transduced LSK cells 2 weeks after BMT. Hoechst staining showed that the percentage of GFP+ LSK cells in G0/G1 was decreased by shN-cad-1 and -2 transduction (23.4% ± 6.1% and 42.1% ± 2.5%, respectively) compared with scramble shRNA (68.8% ± 8.4%) (Figure 2D-E). These data indicate that knockdown of N-cad accelerates the LSK cell cycle after BMT.

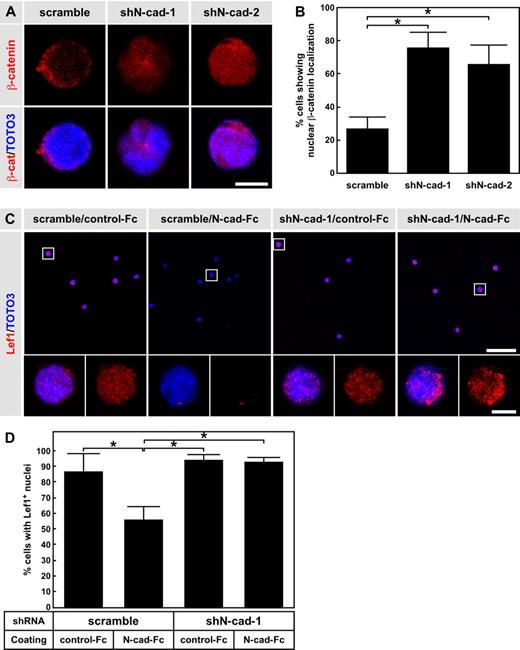

N-cad expression regulates β-catenin

We previously reported that overexpression of N-cad inhibits the nuclear localization/accumulation of β-catenin when cells are grown on N-cad-Fc–coated plates.19 We thus examined the effect of N-cad knockdown on β-catenin localization and Lef1 expression in HSPCs. LSK cells were transduced with scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2, and GFP+ cells (shRNA+ cells) were transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. One month after BMT, we sorted GFP+ LSK cells and examined β-catenin localization. Immunocytochemical staining revealed β-catenin predominantly localized to the nuclei of shN-cad-1– and shN-cad-2–transduced LSK cells. In contrast, scramble shRNA-transduced LSK cells showed juxtamembrane localization of β-catenin after 1 month of BMT (Figure 3A). Overall, shN-cad-1 transduction resulted in the highest percentage of cells with β-catenin nuclear localization (75.8% ± 9.4%), followed by shN-cad-2 (66.0% ± 11.6%), whereas scramble transduction induced only low nuclear localization levels (26.9% ± 7.1%; Figure 3B). We also analyzed β-catenin localization in scramble shRNA–, shN-cad-1–, and shN-cad-2–transduced cells in vitro. No significant differences in β-catenin nuclear localization were observed between scramble shRNA–, shN-cad-1–, and shN-cad-2–transduced cells when they were cultured on control Fc. However, when cells were grown on N-cad-Fc, the percentage of nuclear β-catenin–positive cells was significantly higher after transduction with shN-cad-1 or shN-cad-2 than with scramble shRNA (supplemental Figure 2).

N-cad knockdown enhances nuclear localization of β-catenin and expression levels of Lef-1. (A) Immunocytochemical staining of β-catenin (red). LSK cells were transduced with scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2, and transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. One month after BMT, GFP+ LSK cells were sorted and stained with anti–β-catenin Ab. Scale bar represents 5 μm. (B) Percentage of GFP+ LSK cells showing nuclear β-catenin localization. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .01. (C) Immunocytochemical staining of Lef-1 (red). LSK cells were transduced with scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2, and cultured on control-Fc– or N-cad-Fc–coated plates. After 3 days of culture, GFP+ cells were sorted and stained with anti-Lef1 Ab. The bottom panels represent higher power views of the boxed cells in the top panels. Scale bar represents 50 μm (top panels) and 5 μm (bottom panels). (D) Percentage of cells showing Lef1 expression in the nucleus. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .01.

N-cad knockdown enhances nuclear localization of β-catenin and expression levels of Lef-1. (A) Immunocytochemical staining of β-catenin (red). LSK cells were transduced with scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2, and transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. One month after BMT, GFP+ LSK cells were sorted and stained with anti–β-catenin Ab. Scale bar represents 5 μm. (B) Percentage of GFP+ LSK cells showing nuclear β-catenin localization. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .01. (C) Immunocytochemical staining of Lef-1 (red). LSK cells were transduced with scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2, and cultured on control-Fc– or N-cad-Fc–coated plates. After 3 days of culture, GFP+ cells were sorted and stained with anti-Lef1 Ab. The bottom panels represent higher power views of the boxed cells in the top panels. Scale bar represents 50 μm (top panels) and 5 μm (bottom panels). (D) Percentage of cells showing Lef1 expression in the nucleus. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .01.

Next, we examined Lef1 expression in shRNA-transduced LSK cells after culture on control- or N-cad-Fc (Figure 3C-D). Lef1 expression was induced in both scramble shRNA- and shN-cad-1–transduced cells cultured on control-Fc-coated plates (86.6% ± 11.7% and 94.0% ± 3.5%, respectively; Figure 3D). In contrast, N-cad-Fc reduced the expression level of Lef1 in scramble shRNA-transduced cells, whereas shN-cad-1–transduced LSK cells continued to show nuclear Lef1 expression (55.7% ± 8.6% and 92.73 ± 3.4% for scramble shRNA and shN-cad-1, respectively; Figure 3D). These findings indicate that N-cad expression in HSPCs affects the subcellular localization of β-catenin and the level of Lef1 expression.

N-cad is required for long-term HSPC reconstitution

We recently reported that inhibition of homophilic and heterophilic N-cad interactions via dominant-negative N-cad reduces the LTR activity of HSPCs.19 Thus, we next examined the LTR activity of LSK cells expressing N-cad shRNAs and analyzed the role of N-cad in HSPC engraftment. First, we examined the effects of N-cad shRNAs on colony formation by LSK cells. Although shN-cad-2 mildly reduced the number of colony-forming units in culture, neither N-cad shRNA affected the formation of high proliferative potential colony-forming cells (supplemental Figure 3). We then examined the homing and lodgment activity of shN-cad–transduced cells. Examples of the localization of transplanted donor cells in recipient BM are shown in supplemental Figure 4. HSPC homing activity was not inhibited by N-cad shRNAs (Figure 4A). However, immunohistochemical staining and confocal microscopy of BM sections 36 hours after BMT revealed that N-cad shRNAs altered the lodgment of donor cells. N-cad suppression resulted in an approximately 50% reduction in lodgment capability. After scramble shRNA transduction, 27.6% plus or minus 9.7% of GFP+ donor cells adhered to the bone surface, whereas only 10.9% plus or minus 9.5% and 12.9% plus or minus 6.4% of GFP+ donor cells were adherent to the bone surface after shN-cad-1 and -2 transduction, respectively (Figure 4B). We also examined whether sil.mut.N-cad could rescue this reduced lodgment activity. LSK cells were cotransduced with lentivirus expressing shN-cad-1 and retroviruses expressing control-mKO or sil.mut.N-cad, and then transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice. The transduction of sil.mut.N-cad enhanced the lodgment of donor cells. In addition, coexpression of sil.mut.N-cad rescued the lodgment of shN-cad-1–transduced LSK cells (Figure 4C). These data suggest that N-cad function is required for the lodgment of HSPCs in BM after BMT.

N-cad function is crucial for lodgment but not homing of HSPCs. (A) Effect of N-cad shRNAs on homing of HSPCs to the BM and spleen after BMT. The percentage of GFP+ cells in the BM (left panel) and the spleen (right panel) 36 hours after BMT versus before BMT are shown. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3 per group) from 2 independent experiments. (B) Effects of N-cad shRNA on the lodgment of HSPCs. Percentages of GFP+ bone-adhering cells to total GFP+ cells in BM are shown. A total of 681 cells (scramble), 623 cells (shN-cad-1), and 597 cells (shN-cad-2) from 2 independent experiments were counted. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .01. (C) Rescue of lodgment by sil.mut.N-cad expression. LSK cells were cotransduced with shN-cad-1 and sil.mut.N-cad. Scramble-shRNA, shN-cad-1−/sil.mut.N-cad+, shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.N-cad−, and shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.N-cad+ cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. Thirty-six hours after BMT, the number of GFP+ bone-adhering cells was counted. Percentages of GFP+ bone-adhering cells to total GFP+ cells in BM are shown. A total of 278 cells (scramble), 191 cells (shN-cad-1−/sil.mut.N-cad+), 296 cells (shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.N-cad−), and 301 cells (shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.N-cad+) were counted. Data represent mean ± SD. *P < .01. **P < .05.

N-cad function is crucial for lodgment but not homing of HSPCs. (A) Effect of N-cad shRNAs on homing of HSPCs to the BM and spleen after BMT. The percentage of GFP+ cells in the BM (left panel) and the spleen (right panel) 36 hours after BMT versus before BMT are shown. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3 per group) from 2 independent experiments. (B) Effects of N-cad shRNA on the lodgment of HSPCs. Percentages of GFP+ bone-adhering cells to total GFP+ cells in BM are shown. A total of 681 cells (scramble), 623 cells (shN-cad-1), and 597 cells (shN-cad-2) from 2 independent experiments were counted. Data are mean ± SD. *P < .01. (C) Rescue of lodgment by sil.mut.N-cad expression. LSK cells were cotransduced with shN-cad-1 and sil.mut.N-cad. Scramble-shRNA, shN-cad-1−/sil.mut.N-cad+, shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.N-cad−, and shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.N-cad+ cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. Thirty-six hours after BMT, the number of GFP+ bone-adhering cells was counted. Percentages of GFP+ bone-adhering cells to total GFP+ cells in BM are shown. A total of 278 cells (scramble), 191 cells (shN-cad-1−/sil.mut.N-cad+), 296 cells (shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.N-cad−), and 301 cells (shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.N-cad+) were counted. Data represent mean ± SD. *P < .01. **P < .05.

We then analyzed the LTR capability of LSK cells transduced with scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, or shN-cad-2 (1 × 104 cells/recipient mouse). We found that the transduction of both shN-cad-1 and -2 significantly reduced the engraftment of donor cells in recipient mice, whereas scramble shRNA-transduced LSK cells retained their capacity for long-term engraftment (Figure 5). Engraftment was observed in 14.2% plus or minus 0.9%, 0.27% plus or minus 0.16%, and 0.04% plus or minus 0.035% of donor cells transduced with scramble shRNA, shN-cad-1, and shN-cad-1, respectively. Because continuous activation of β-catenin has been reported to induce the exhaustion of the stem cell pool by accelerating the cell cycle and blocking LT-HSC differentiation,27,28 we examined the effect of N-cad shRNAs on the differentiation of shN-cad–transduced donor cells. Although the number of GFP+ donor-derived cells overexpressing N-cad shRNAs in recipient mice was extremely low, both shN-cad-1– and -2–transduced cells differentiated into T, B, and myeloid lineages (supplemental Figure 5). These data suggest that N-cad function is required for BM reconstitution but not for multilineage differentiation of HSPCs.

N-cad function is required for the LTR activity of HSPCs. (A) Effects of N-cad shRNA on the LTR activity of HSPCs. The percentages of GFP+ donor-derived (Ly5.1+) cells in recipient mice 1 to 3 months after BMT are shown. Overexpression of shN-cad-1 and -2 significantly suppressed LTR of donor LSK cells. Data are mean ± SD (n = 10/group) from 3 independent experiments. (B) Representative FACS plots of PB analysis of shRNA-transduced donor cells 3 months after BMT.

N-cad function is required for the LTR activity of HSPCs. (A) Effects of N-cad shRNA on the LTR activity of HSPCs. The percentages of GFP+ donor-derived (Ly5.1+) cells in recipient mice 1 to 3 months after BMT are shown. Overexpression of shN-cad-1 and -2 significantly suppressed LTR of donor LSK cells. Data are mean ± SD (n = 10/group) from 3 independent experiments. (B) Representative FACS plots of PB analysis of shRNA-transduced donor cells 3 months after BMT.

Silent mutant N-cad rescues N-cad shRNA-induced LTR defects

Recently, Kiel et al15 reported that N-cad conditional knockout mice do not show defects in HSC maintenance. Therefore, we carefully examined whether the defective LTR activity of shN-cad–transduced LSK cells was rescued by shRNA-resistant N-cad and tested the specificity of the N-cad shRNAs used in this study. For the rescue experiments, LSK cells were cotransduced with lentivirus expressing shN-cad-1 and retrovirus expressing control-mKO or sil.mut.N-cad (Figure 6A). After lentivirus and retrovirus transduction, LSK cells (sil.mut.N-cad+/shN-cad-1−, sil.mut.N-cad+/shN-cad-1+, sil.mut.N-cad−/shN-cad-1+, and scramble shRNA) were sorted and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice (1.5 × 104 cells/recipient mouse). We confirmed that sil.mut.N-cad−/shN-cad-1+ cells did not reconstitute hematopoiesis in the recipient, even 6 months after BMT (Figure 6B). The percentage of donor cells among PB, BM MNCs, and BM LSK cells was 0.2% plus or minus 0.09%, 0.7% plus or minus 0.4%, and 0.6% plus or minus 0.3%, respectively. Cotransduction of sil.mut.N-cad rescued the engraftment of shN-cad–expressing cells in all tested cell populations (Figure 6B-D). The percentage of donor cells was comparable in sil.mut.N-cad+/shN-cad-1+ cells (9.4% ± 4.7% in PB, 2.6% ± 1.8% in BM MNCs, and 5.8% ± 2.1% in LSK), scramble shRNA-expressing cells (4.3% ± 1.4% in PB, 2.9% ± 1.3% in BM MNCs, and 5.6% ± 1.0% in LSK), and sil.mut.N-cad+/shN-cad-1− cells (5.7% ± 0.9% in PB, 2.5% ± 1.8% in BM MNCs, and 4.8% ± 1.3% in LSK). We also examined engraftment of N-cad shRNA-transduced cells in the spleen, which lacks an osteoblastic niche. Notably, sil.mut.N-cad−/shN-cad-1+ cells reconstituted MNCs and LSK cells in the spleen (Figure 6E-F). The percentages of donor cells observed in MNCs were 2.6% plus or minus 0.2% (scramble), 3.4% plus or minus 0.9% (sil.mut.N-cad+/shN-cad-1−), 2.0% plus or minus 0.8% (sil.mut.N-cad−/shN-cad-1+), and 4.2% plus or minus 1.5% (sil.mut.N-cad+/shN-cad-1+), and in LSK cells were 4.8% plus or minus 0.9% (scramble), 6.6% plus or minus 1.2% (sil.mut.N-cad+/shN-cad-1−), 5.4% plus or minus 0.7% (sil.mut.N-cad−/shN-cad-1+), and 6.2% plus or minus 1.5% (sil.mut.N-cad+/shN-cad-1+). These findings suggest that N-cad–mediated cell adhesion is specifically required for long-term reconstitution of HSPCs in the BM niche.

Rescue of the engraftment capacity of N-cad shRNA-transduced cells. (A) LSK cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing shN-cad-1 (GFP) and retrovirus expressing sil.mut.N-cad (mKO). After gene transduction, GFP−mKO+ (shN-cad-1−/sil.mut.N-cad+), GFP+mKO+ (shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.-N-cad+), and GFP+mKO− (shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.-cad−) cells were sorted and transplanted into lethally irradiated mice with 2 × 105 competitor cells. Scramble shRNA-transduced cells were used as a control. Six months after BMT, the percentage of donor-derived cells in PB (B), BM MNCs (C), BM LSK cells (D), spleen MNCs (E), and spleen LSK cells (F) was analyzed. Cotransduction with sil.mut.N-cad rescued the LSK cell engraftment capacity that was lost after shN-cad transduction alone. Data are mean ± SD; n = 5/group. *P < .01. Note that shN-cad-1–transduced cells showed long-term engraftment in the spleen.

Rescue of the engraftment capacity of N-cad shRNA-transduced cells. (A) LSK cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing shN-cad-1 (GFP) and retrovirus expressing sil.mut.N-cad (mKO). After gene transduction, GFP−mKO+ (shN-cad-1−/sil.mut.N-cad+), GFP+mKO+ (shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.-N-cad+), and GFP+mKO− (shN-cad-1+/sil.mut.-cad−) cells were sorted and transplanted into lethally irradiated mice with 2 × 105 competitor cells. Scramble shRNA-transduced cells were used as a control. Six months after BMT, the percentage of donor-derived cells in PB (B), BM MNCs (C), BM LSK cells (D), spleen MNCs (E), and spleen LSK cells (F) was analyzed. Cotransduction with sil.mut.N-cad rescued the LSK cell engraftment capacity that was lost after shN-cad transduction alone. Data are mean ± SD; n = 5/group. *P < .01. Note that shN-cad-1–transduced cells showed long-term engraftment in the spleen.

Discussion

The interaction of HSCs with their niche is critical for maintaining normal hematopoiesis. We and other groups have shown that N-cad is expressed in LT-HSCs and a subpopulation of osteoblasts in adult BM,7,16-19 indicating that direct cell-cell interactions between HSCs and their niche are involved in sustaining the HSC pool. However, there are several discrepancies in the studies of the expression and function of N-cad in HSCs. Recently, Li and Zon published a forum article.29 In the article, they summarized the points as follows: (1) N-cad expression in HSCs is either low or undetectable; (2) N-cad mAb, MNCD2, is not suitable for flow cytometry; and (3) N-cad is not required for the maintenance of HSCs. Concerning points 1 and 2, the new FACS-suited anti–N-cad Ab is needed to conclude N-cad expression in HSCs. Concerning the results of N-cad conditional knockout mice, the differences observed between the knockout experiments and our knockdown experiments might be the result of differences in gene product dose. In addition, there was a possibility of the cadherin redundancy or compensation by some other molecules that may have masked the deletion of functions of N-cad. More detailed studies might be required. The present study has demonstrated that acute silencing of N-cad by shRNA results in enhanced cell division (Figure 2) and reduced long-term engraftment activity of HSPCs in BM (Figures 5–6). Further studies revealed that these results were not the result of off-target effects of the shRNAs. Rather, the impaired BM reconstitution of N-cad shRNA-transduced LSK cells was rescued by cotransduction with sil.mut.N-cad (Figure 6). In addition, cotransduction of sil.mut.N-cad rescued N-cad shRNA-mediated accelerated cell division (Figure 2). These findings indicate that sh-Ncad-1 and -2 specifically reduced N-cad expression in HSPCs. The N-cad shRNAs used in this study did not affect the expression of other cadherins in transduced LSK cells, indicating that the defect of HSPC maintenance induced by acute silencing of N-cad is specific and nonredundant. However, overexpression experiments and BMT assays performed in this study require the cell-cycle activation of HSPCs before the retrovirus- or lentivirus-mediated gene transduction; thus, the HSPCs undergo the severe stress more than the normal BMT experiment. Therefore, further work is needed to clarify the physiologic function of N-cad in HSPCs.

Recently, we reported that overexpression of N-cad in HSCs induced a slower rate of division, resulting in the protection of HSCs against stresses, including serial BMT or myelosuppression.19 In this study, the inhibition of N-cad–mediated cell adhesion led to increased HSPC proliferation (Figure 2). These findings suggest a strong correlation between cell adhesion and the quiescent state of HSPCs. Indeed, mutant mice, such as those lacking PTEN, Rb, and JunB, showed an increase in HSC cycling and mobilization from the BM to peripheral circulation, which was accompanied by an increase in HSC number in the short term but set the stage for disease development.30-33 In addition, N-cad is down-regulated in HSPCs before detachment from the niche and reentry into the cell cycle.34 Immunocytochemical staining clearly demonstrated that N-cad expression levels affect β-catenin localization and Lef1 expression (Figure 3). N-cad shRNA enhanced the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and Lef1, which may be responsible for the accelerated HSPC cell division we observed. Excessive activation of β-catenin has been shown to reduce cell-cycle quiescence, resulting in HSC exhaustion.27,28 Blocking canonical Wnt signaling also reduced HSC quiescence and LTR activity.35

Our results suggest that N-cad may function as a regulator of β-catenin activity in HSPCs. However, the phenotype of constitutive β-catenin activation only partially overlaps with the phenotype of N-cad knockdown HSPCs.27,28 Constitutively active β-catenin transgenic mouse HSCs showed blocked multilineage differentiation and reduced colony formation, whereas shN-cad–transduced cells did not show a significant impairment of differentiation after BMT (supplemental Figure 5). These observations suggest that cell adhesion-dependent mechanisms also play a critical role in the regulation of the quiescence of HSCs. We hypothesize that the loss of N-cad–mediated cell-cell interaction may induce the activation of stem/progenitors at an early stage while later reducing the quiescent HSC population.

Inhibition of cadherin-mediated cell adhesion by the transduction of DN-N-cad induced impaired LTR activity of HSCs.19 In this study, we analyzed the function of N-cad in HSPCs after BMT because DN-N-cad inhibits not only N-cad but also other cadherins, such as E-cad.36 BMT assay clearly demonstrated that the transduction of shN-cad in LSK cells induced a significant reduction in the engraftment of donor cells. Although our study did not examine the specific physiologic functions of N-cad in LT-HSCs, the present data indicate that N-cad is required for lodgment and the subsequent steps of BM reconstitution, including niche occupancy and HSC protection from stress.

Although N-cad–mediated cell-cell contact between HSCs and endosteal osteoblasts and other supporting cell types in the BM appears crucial for the establishment of BM hematopoiesis after BMT, N-cad shRNA-transduced cells showed long-term engraftment in the spleen (Figure 6), which lacks an osteoblastic niche. These data suggest that the spleen presents a different (N-cad–independent) microenvironment for hematopoietic reconstitution and indicate that N-cad–mediated cell-cell interaction is specifically required for the regulation of HSPCs in the BM niche. Although osteoblasts are a key component of the niche regulation of HSPCs, we cannot rule out N-cad homophilic and heterophilic interactions between HSPCs and other supporting cells, such as endothelial cells in the BM. Indeed, endothelial cells have been shown to express N-cad,37,38 and N-cad can bind to other cadherin subtypes.20-22 Thus, the physiologic role of cadherin-based cell-cell adhesion of HSPCs to their niche cells under steady-state conditions remains to be investigated.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research and a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists), and by the High-Tech Research Center Project for Private Universities, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (matching fund subsidy).

Authorship

Contribution: K.H., F.A., H.Y., H.I., Y.N., and Y.G. performed experiments; K.H. and F.A. analyzed results and made the figures; and F.A. and T.S. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Fumio Arai, Department of Cell Differentiation, Sakaguchi Laboratory of Developmental Biology, School of Medicine, Keio University, 35 Shinano-machi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 160-8582, Japan; e-mail: farai@sc.itc.keio.ac.jp; and Toshio Suda, Department of Cell Differentiation, Sakaguchi Laboratory of Developmental Biology, School of Medicine, Keio University, 35 Shinano-machi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 160-8582, Japan; e-mail: sudato@sc.itc.keio.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

K.H. and F.A. contributed equally to this study.