Lymphatic vessels were missed by many pathologists for centuries because they do not contain red blood cells. Yet the reason for this has been illuminated only now in several articles in Blood.

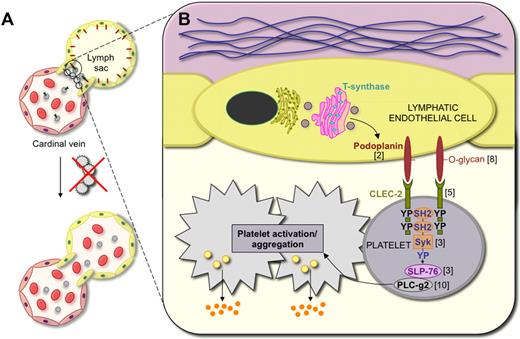

A schematic view of the mechanisms of blood vessel–lymphatic vessel separation. (A) In embryos, the lymphatic vessels develop from embryonic veins. The junction between the anterior cardinal vein and the first lymphatic vessel structure, called the lymph sac, is closed by a platelet plug. However, various defects of platelets allow blood entry into the lymphatic vessels. (B) Podoplanin is O-glycosylated during its biosynthesis in lymphatic endothelial cells. Cell surface–exposed podoplanin provides binding sites for the platelet receptor CLEC-2. Podoplanin-bound CLEC-2 activates the Syk tyrosine kinase and SLP-76 adaptor protein, which leads to downstream activation of phospholipase C-gamma2 (PLC-g2), with resulting platelet activation including release of platelet alpha granules. The numbers next to the various molecules correspond to the references reporting the deletion phenotypes, for example, PLC-g2.10

A schematic view of the mechanisms of blood vessel–lymphatic vessel separation. (A) In embryos, the lymphatic vessels develop from embryonic veins. The junction between the anterior cardinal vein and the first lymphatic vessel structure, called the lymph sac, is closed by a platelet plug. However, various defects of platelets allow blood entry into the lymphatic vessels. (B) Podoplanin is O-glycosylated during its biosynthesis in lymphatic endothelial cells. Cell surface–exposed podoplanin provides binding sites for the platelet receptor CLEC-2. Podoplanin-bound CLEC-2 activates the Syk tyrosine kinase and SLP-76 adaptor protein, which leads to downstream activation of phospholipase C-gamma2 (PLC-g2), with resulting platelet activation including release of platelet alpha granules. The numbers next to the various molecules correspond to the references reporting the deletion phenotypes, for example, PLC-g2.10

The main function of the lymphatic vessels is to return excess tissue fluid to the blood circulation. Other functions include antigen monitoring via the sieving function of the lymph nodes, and dietary lipid transport in chylomicrons via the intestinal lymph vessels.1 For the lymphatic vascular system to operate efficiently, the lymphatic vessels must separate from the blood vessels during development and the connections with the blood vessel lumen remain unidirectional at the sites where lymph drains into blood at the subclavian veins. Prior to reports in this and other recent issues of Blood, the mechanisms behind this separation and the reason for the leakage of blood into lymphatic vessels in several mouse mutant models were unknown. Now, it seems that the mystery has largely been resolved. The new evidence does not indicate a role for circulating endothelial progenitor cells as first suspected, but instead uncovers an important function for platelets, which are recruited to prevent the entry of blood into lymphatic vessels.

A schematic view of the new concepts of lymphatic-blood vascular separation is shown in the figure. In developing embryos, platelets aggregate and form a clot at sites where paired lymph sacs and lymphatic vessels emerging from them connect with their parental anterior cardinal veins. According to the recent results of Dontscho Kerjaschki, platelet aggregation at these sites is triggered by the O-glycosylated mucoprotein podoplanin, named after its main expression site in kidney podocytes and which was found to be specifically expressed in lymphatic, but not blood vascular, endothelial cells.2 Some of the earliest findings on the failure of lymphatic-blood vascular separation dealt with mice carrying homozygous mutations of the gene encoding the Syk tyrosine kinase or its adaptor protein SLP-76 (Lcp2).3 Selective Syk and SLP-76 expression in hematopoietic cells suggested initially that the mutations could compromise a rare cell population that was believed to contribute to at least some of the endothelial cells involved in (lymph)angiogenesis.3,4 However, in this issue of Blood, Bertozzi et al instead propose that the Syk protein of platelets is critical in ensuring lymphatic-blood vascular separation.5 Additional recent findings indicate that the deletion of Syk also induces an excess of tissue leukocytes that produce sufficient amount of the lymphangiogenic factors vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)–C and -D to stimulate lymphatic hyperproliferation, eventually resulting in anastomoses between the developing lymphatic and blood vessels elsewhere in the developing embryo.6 A somewhat similar phenotype also occurs in mice deficient in 2 suppressors of phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase–extracellular receptor kinase downstream of VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 signaling.7

Podoplanin in lymphatic endothelial cells is critical for platelet activation where the podoplanin-positive lymphatic vessels are separated from the cardinal veins as shown in studies of podoplanin knockout embryos.2 Podoplanin binds to and activates the C-type lectin receptor 2 (CLEC-2), specifically expressed in platelets, which in turn leads to activation of Syk and phosphorylation of SLP-76.2 This then triggers the platelet aggregation that shuts off the leakage of blood into the lymphatic vascular system. Consistent with these findings, mice lacking the glycosyltransferase T-synthase (encoded by the C1galt1 gene) in hematopoietic and endothelial cells also exhibit incomplete separation of blood and lymphatic vessels as O-glycosylated podoplanin levels are thereby reduced.8 Interestingly, other phenotypes where blood is found inside the lymphatic vessels include mice lacking platelets (Meis gene deletion9 ) or platelet-derived growth factor-B (PDGF-B; C. Betsholtz, P. Haiko, G.D. and K.A., unpublished observations). However, the mechanisms behind this phenotype have not yet been worked out.

This flurry of papers points to the fact that platelets are functional and required in utero, contrary to what was formerly believed. They also raise important questions that should be further investigated. For example, is podoplanin, also known as aggrin for its potent platelet aggregating property, involved in blood coagulation in pathologic processes in adults? Do the alpha granules released from activated platelets contain further molecules that help to reinforce the blood vascular/lymphatic junction? The answers to these questions should be highly significant for our understanding of both vascular and platelet biology.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ■