Abstract

Therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes (t-MDSs) and acute myeloid leukemia (t-AML) have a poor prognosis with conventional therapy. Encouraging results are reported after allogeneic transplantation. We analyzed outcomes in 868 persons with t-AML (n = 545) or t-MDS (n = 323) receiving allogeneic transplants from 1990 to 2004. A myeloablative regimen was used for conditioning in 77%. Treatment-related mortality (TRM) and relapse were 41% (95% confidence interval [CI], 38-44) and 27% (24-30) at 1 year and 48% (44-51) and 31% (28-34) at 5 years, respectively. Disease-free (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were 32% (95% CI, 29-36) and 37% (34-41) at 1 year and 21% (18-24) and 22% (19-26) at 5 years, respectively. In multivariate analysis, 4 risk factors had adverse impacts on DFS and OS: (1) age older than 35 years; (2) poor-risk cytogenetics; (3) t-AML not in remission or advanced t-MDS; and (4) donor other than an HLA-identical sibling or a partially or well-matched unrelated donor. Five-year survival for subjects with none, 1, 2, 3, or 4 of these risk factors was 50% (95% CI, 38-61), 26% (20-31), 21% (16-26), 10% (5-15), and 4% (0-16), respectively (P < .001). These data permit a more precise prediction of outcome and identify subjects most likely to benefit from allogeneic transplantation.

Introduction

Use of leukemogenic drugs and ionizing radiation to treat diverse cancers has resulted in an increased incidence of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes (t-MDSs) and acute myeloid leukemia (t-AML). These disorders have a poor prognosis with conventional antileukemia therapies with median survival of 1 year or less.1 This outcome is related to several factors including older age, worse performance score, comorbidities, therapy resistance, and bone marrow failure. Cytogenetic abnormalities associated with a poor prognosis in non–therapy-related MDS and AML, such as del (7/7q) or a complex karyotype, are common in t-MDS and t-AML.2,3 Patients presenting with t-MDS often progress to t-AML. These disorders are also described after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).4-9

In the 1990s, it was recognized that a separate form of therapy-related leukemia arose after treatment with topoisomerase-II inhibitors.1 These therapy-related leukemias differ from the aforementioned therapy-related leukemias by virtue of a shorter latency, no antecedent myelodysplastic phase, and balanced translocations involving 11q23 and 21q22. Therapy options for persons with t-MDS or t-AML include intensive induction chemotherapy,10 hematopoietic growth factors, low-dose cytosine arabinoside, retinoids, and 5-azacytidine or decitabine. Long-term results with these therapies are disappointing.11-14

Allogeneic transplantations in t-AML and t-MDS are typically restricted to younger persons without comorbidities and a good performance score because of the high treatment-related mortality (TRM) associated with this procedure. Consequently, most reports are of small numbers of subjects, precluding the careful identification of variables associated with transplantation outcomes.15,16 We reviewed data reported to the Center for International Bone Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) to address this issue.

Methods

Data collection

The CIBMTR was established in 2004 through a formal affiliation of the research division of the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP; established in 1986) and the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry (established in 1972). Detailed demographic, disease, and transplant characteristics and outcome data are collected on all consecutive related and unrelated donor (URD) allogeneic transplantations at more than 500 participating centers. Computerized error checks, physician review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers improve data quality.

Inclusion criteria

The study included all patients, both pediatric and adult, who received peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) or bone marrow grafts from a related or volunteer URD for t-MDS or t-AML and reported to the CIBMTR between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2004. They had received prior cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy and were reported to the CIBMTR with a diagnosis of t-MDS or t-AML. Recipients of syngeneic or cord blood transplants, patients with cytogenetic information consistent with a diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and patients with de novo AML or MDS who had an antecedent hematologic disorder were excluded. Consent procedures for data collection and analysis were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the NMDP and the Medical College of Wisconsin for the CIBMTR.

Unfavorable, intermediate, or favorable risk cytogenetics were assigned according to Slovak et al for AML patients.17 Cytogenetics for MDS (good, intermediate, or poor risk) were classified based upon the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS).18

For analysis, MDS was classified as either early (refractory anemia, acquired idiopathic sideroblastic anemia, unspecified MDS, or pre-HCT marrow blasts < 5%) or advanced (refractory anemia excess blasts [RAEB], refractory anemia excess blasts in transformation [RAEB-t], chronic myelomonocytic leukemia [CMML], or marrow blasts ≥ 5%).

End points

Neutrophil recovery was defined as achieving an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5 × 109/L or higher for 3 consecutive days; platelet recovery was defined as achieving a platelet count of 20 × 109/L or higher, unsupported by transfusions for 7 days. Incidences of grades II, III, and IV acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and chronic GVHD were determined in all patients.19-21 Treatment-related mortality (TRM) was defined as death during a continuous complete remission (CR). Relapse was defined as hematologic recurrence of t-AML or t-MDS; patients without CR after HCT were considered to have had a recurrence at day +1. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as time to treatment failure (relapse or death). For analyses of overall survival, failure was death from any cause; surviving patients were censored at the date of last contact.

Statistical analysis

Univariate probabilities of DFS and overall survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, with standard error estimated by Greenwood's formula. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated using log-transformed intervals. Probabilities of TRM and leukemia relapse were calculated using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate competing risks. Potential prognostic factors for outcomes of interest were evaluated in a multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression. The variables considered for inclusion within the multivariate analysis are marked in Table 1 and additionally included sex, FAB subtype (M0-M2 vs M3 vs M4-M7 vs other/unclassified (for t-AML); refractory anemia or refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts versus other MDS (for t-MDS), IPSS score at diagnosis (low or intermediate-1 vs intermediate-2 or high vs unknown), extramedullary disease (no vs yes), IPSS score at allogeneic transplantation (low or intermediate-1 vs intermediate-2 or high vs unknown), WBC count at allogeneic transplantation (≤ 10 vs 10-100 vs > 100 × 109/L vs unknown), donor-recipient sex match (female-male vs others vs unknown), donor sex (parous female vs male vs nonparous female vs unknown), donor-recipient cytomegalovirus status (D−/R− vs D+/R− vs recipient positive vs unknown), year of transplantation (1990-1994 vs 1995-1999 vs 2000-2004), and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor growth factors to promote engraftment after transplantation (no vs yes). The optimal time cut point for age at transplantation was determined by the maximum likelihood method. All computations were made using the proportional hazards regression procedure in the statistical package of SAS Version 9. Forward stepwise variable selection at a .01 significance level was used to identify covariates associated with the main outcome. In each model, the assumption of proportional hazards was tested for each variable using a time-dependent covariate; when this indicated differential effects over time (nonproportional hazards), models were constructed breaking the posttransplantation course into 2 time periods using the maximized partial likelihood method to find the most appropriate breakpoint. Examination for center effects used a random effects or frailty model. We found no evidence of correlation between center and any of the outcomes. All P values are 2-sided.

Results

Patients

A total of 868 patients met the inclusion criteria and were treated between 1990 and 2004 at 211 reporting centers from 33 different countries. The median follow-up of survivors was 61 months (range, 3-187 months). Tables 1 and 2 show the patient, disease, and transplant-related characteristics of the 868 patients. The median age was 40 years; 20% were younger than 19 years and 6% were older than 60 years. There was a slight female predominance. A pretransplantation diagnosis of t-AML was made in two-thirds of the patients and t-MDS in one-third. Nearly half of the patients had a prior history of lymphoma, 16% had breast cancer, and 12% had ALL. Less than 10% each had other malignancies or autoimmune disorders. The median time of diagnosis from prior disease to the t-MDS or t-AML was 4 years (range, < 1-28 years). Only limited details on prior cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation therapy were available. Half of the patients had received radiation therapy either alone or in combination with other therapy. Seventeen percent of the patients had undergone a prior autologous HCT.

For the t-AML patients, 30% had a documented prior t-MDS. Only 9% had favorable prognosis cytogenetic abnormalities. Sixty percent had no abnormalities or those of an intermediate prognosis, and one-third had poor-risk cytogenetics. Half of the t-AML patients were in CR1 at the time of transplantation; the remaining patients were beyond CR2, were in relapse, or had primary induction failure. One-third of the t-MDS patients had prior therapy before allogeneic transplantation.

A myeloablative regimen for transplantation was used in 77% of patients. Of the patients undergoing a reduced-intensity/nonmyeloablative transplantation, 36% had had a prior autologous transplantation compared with only 12% of patients undergoing a myeloablative transplantation who had a prior autologous transplantation (P < .001). Ninety-three percent of the reduced-intensity/nonmyeloablative transplantations were performed between the years 2000 and 2004 compared with the myeloablative transplantations that were more evenly distributed over the time span of the study (P < .001). Thirty-three percent had an HLA-matched sibling donor and the remaining patients had a partially matched relative or an URD.22 Bone marrow was the source of allogeneic hematopoietic cells in two-thirds of the patients. GVHD prophylaxis included cyclosporine and methotrexate in nearly half of the patients.

Treatment-related mortality

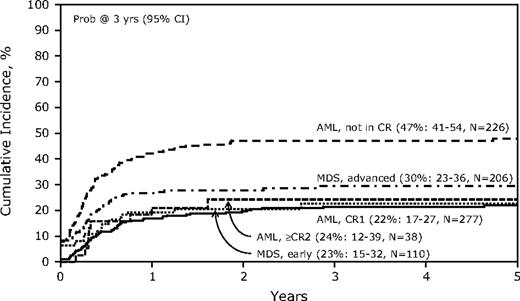

Table 3 shows the univariate analyses for key outcomes for the study. The TRM was 41% (95% confidence interval [CI], 38-44) at 1 year and 48% (44-51) had nonrelapse TRM at 5 years. Multivariate analysis (Table 4) for TRM identified age older than 35 years, a lower Karnofsky performance score, and any t-MDS before allogeneic transplantation as significantly unfavorable covariates. Recipients of grafts from a non–HLA-matched sibling related donor or a mismatched URD also had higher TRM compared with recipients of grafts from an HLA-matched sibling donor. Of note, the use of a reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimen was not associated with reduced TRM (data not shown). The cumulative incidence of TRM categorized by disease and disease phase is shown in Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of treatment-related mortality by disease status at transplantation after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplactic syndrome (MDS).

Cumulative incidence of treatment-related mortality by disease status at transplantation after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplactic syndrome (MDS).

GVHD

The incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD (aGVHD) at 100 days after transplantation was 39% (range, 35%-42%). Chronic GVHD occurred in 27% (range, 24%-30%) and 30% (range, 27%-33%) of patients at 1 and 5 years after transplantation, respectively (Table 3).

Relapse

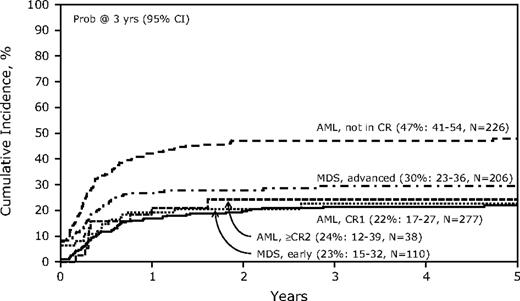

The overall risk of relapse was 27% (range, 24%-30%) at 1 year and 31% (range, 28%-34%) at 5 years (Table 3). Multivariate analysis for relapse is shown in Table 4. Risk factors for relapse included age older than 35 years, a prior diagnosis of ALL, poor-risk cytogenetics, and t-AML not in remission at the time of HCT. The cumulative incidence of relapse by diagnosis and disease status is shown in Figure 2. Among the differing disease status categories for t-AML and t-MDS, only patients not in remission at the time of transplantation had a higher incidence of posttransplantation disease relapse (relative risk = 3.36, 95% CI, 2.44-4.64, P < .001).

Cumulative incidence of relapse by disease status at transplantation after allogeneic HCT for therapy-related AML and MDS.

Cumulative incidence of relapse by disease status at transplantation after allogeneic HCT for therapy-related AML and MDS.

Disease-free survival

Disease-free survival was 32% (range, 29%-36%) at 1 year and 21% (range, 18%-24%) at 5 years. Multivariate analysis for treatment failure (death or relapse) demonstrated that age older than 35 years, poor-risk cytogenetics, t-AML not in CR, advanced t-MDS, and a nonsibling related donor or a mismatched URD were each significantly associated with worse DFS (data not shown). Figure 3A and B show DFS by diagnosis, disease status, and donor type.

Probability of survival. (A) Disease-free survival by disease status at transplantation, (B) leukemia-free survival by type of donor, and (C) overall survival by disease status at transplantation after allogeneic HCT for therapy-related AML and MDS.

Probability of survival. (A) Disease-free survival by disease status at transplantation, (B) leukemia-free survival by type of donor, and (C) overall survival by disease status at transplantation after allogeneic HCT for therapy-related AML and MDS.

Overall survival

The overall survival (OS) for all patients was 37% (range, 34%-41%) at 1 year and 22% (range, 19%-26%) at 5 years. Significant factors in multivariate analysis were similar to those for DFS and included age older than 35 years, poor-risk cytogenetics, t-AML not in CR, advanced t-MDS, and a related donor other than a sibling or a mismatched URD (Table 4). Figure 3C shows probability of overall survival by diagnosis and disease status at transplantation. Causes of death included relapse in one-third of patients, regimen-related toxicity in 22%, infection in 15%, GVHD in 11%, respiratory failure in 9%, graft failure in 2%, and other causes in 7%.

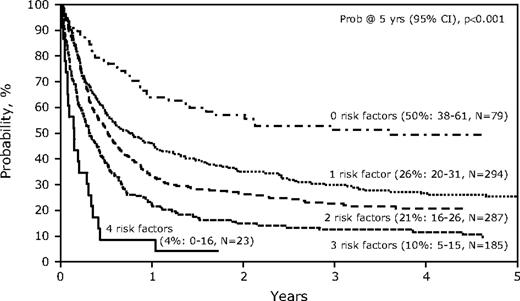

Risk factors for survival

Age older than 35 years, poor-risk cytogenetics, disease not in remission at time of HCT, and donor type (nonsibling related donor or mismatched URD) were each identified as poor risk factors with similar relative risks for posttransplantation survival. The presence of each of these factors resulted in added adverse effect on survival and stratified 5 groups with distinct outcomes according the number of factors present (Figure 4). Patients with no risk factors had a 5-year survival of 50% (range, 38%-61%), whereas 1 risk factor yielded survival of only 26% (range, 20%-31%) at 5 years, with subsequent decrements with increasing number of risk factors: 2 risk factors 21% (range, 16%-26%), 3 risk factors 10% (range, 5%-15%), and 4 risk factors 4% (range, 0%-16%; P < .001). Because each of these risk factors had a similar hazard ratio, a simple scoring system based on the number of risk factors can predict survival.

Probability of overall survival after allogeneic HCT for therapy-related AML and MDS, by risk factors.

Probability of overall survival after allogeneic HCT for therapy-related AML and MDS, by risk factors.

Discussion

This study, the largest reported series of allogeneic transplantation for t-AML or t-MDS, spanned a 15-year period, included patients from 33 different countries, and gives an excellent broad perspective (without the limitations of publication bias) on the challenges of managing these serious late complications of cancer therapy. The study population largely comprises high-risk patients. Nonrelapse mortality was high and approached nearly 50% at 5 years after transplantation. Disappointingly, TRM was not reduced in patients receiving a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen, but may have related to the significant proportion of patients in this group who had had a prior autologous transplantation. Risk of relapse was expectedly high, at just more than 30%, resulting in leukemia-free and overall survival of 21% and 22%, respectively, at 5 years. Age older than 35 years, poor-risk cytogenetics, inadequate disease control at the time of transplantation, and less well-matched donors were all associated with a poor outcome. Combining these poor-risk features in a simple scoring system demonstrated a significant reduction in survival accompanying even one of these risk factors. Patients without any of these risk factors had an outcome comparable with transplantation for de novo AML/MDS,17,23 but represented less than 10% of the overall population. In addition, in the younger favorable group, patients younger than 20 years fared no better than patients aged 20 to 35 years, as TRM, relapse incidence, OS, and DFS were similar between the these 2 younger age groups (P > .4, data not shown). This predictive model needs to be interpreted cautiously as it has not been validated prospectively.

Several studies of allogeneic HCT for t-MDS/t-AML have been reported. Investigators in Boston described 18 patients (median age, 32 years) who underwent transplantation between 1980 and 1994 and compared the outcomes to 25 patients with primary MDS.24 DFS was 24% for the patients with therapy-induced and 43% for primary MDS. The TRM was 50% and 60% for therapy-induced and primary MDS, respectively.

Hale et al have previously reported the results in 21 children who developed epipodophyllotoxin-associated AML.25 Induction chemotherapy was administered to 13 of 21 patients before transplantation. Allogeneic HCT yielded a 3-year DFS of 19%.

A French study of 70 patients26 reported an estimated 2-year overall survival of 30% and, similar to data reported here, identified the following as associated with a poor outcome: older age, male sex, cytomegalovirus-positive recipient, not in CR at HCT, and intensive conditioning.

An alternative, but rarely tested, therapeutic approach is autologous HCT. A series of 65 patients (t-AML, n = 56; t-RAEB or RAEB-t, n = 4) was reported by the European Group for Bone Marrow Transplant (EBMT).27 Despite substantial selection bias inherent in eligibility for autografting, outcomes were similar or better than those reported with allogeneic HCT. Three-year OS and DFS were 35% and 32%, respectively. TRM was only 12%, but relapse was 48% for those in CR and 83% if not in CR. This study suggests that some carefully selected patients with t-MDS or t-AML in CR may benefit from autologous HCT.

A recent report from the EBMT described the outcome of allogeneic HCT for t-MDS/t-AML in 461 patients: 308 (67%) had AML and 57% were in CR.28 The 3-year relapse-free and overall survivals were 33% and 35%, respectively. Significant variables for event-free or overall survival were older age, abnormal cytogenetics, and not being in CR.

The limitations of our study include its derivation from an observational database and that decisions regarding treatment and timing of transplantation were made by individual transplantation centers. The study spanned a 15-year period and modern differences in practice could have changed posttransplantation outcomes. However, the year of transplantation was included in the multivariate analysis and it did not significantly affect any of the reported outcomes. In our large multicenter, multinational registry we could not fully analyze details from the initial therapy of the primary malignancy, which could also predict outcomes. As a large registry study, this information is essentially impossible to obtain and its absence does not diminish our assessment of the overall outcomes after allogeneic HCT.

Allogeneic HCT remains the only curative therapy for t-MDS and t-AML. These data highlight important pretransplantation risk factors determining success and identify a subset of patients with a favorable outcome. We propose that this scoring system be considered for all patients with t-MDS and t-AML. Our scoring is similar to an earlier EBMT score for assessing HCT risk in CML patients.29 We suggest that offering HCT to patients with 0, 1, or 2 risk factors could be considered, but that the outcome in patients with 3 or 4 risk factors appears quite dismal and alternative therapies should be sought for these patients. The intensity of the conditioning regimen, the type of GVHD prophylaxis, and the source of the graft (bone marrow or peripheral blood) did not have a significant impact on outcome, so modifying these variables with currently available techniques does not appear fruitful.

A primary consideration for physicians providing management of patients at risk for treatment-associated cancers is prevention through avoidance of extended carcinogenic therapy. However, for those unfortunate enough to develop t-AML and t-MDS, allogeneic HCT can be curative. Future progress for these patients will depend on identifying new noncarcinogenic therapies for the treatment of primary disorders and developing more effective and safer therapies for t-AML and t-MDS.30 Augmented transplantation approaches that limit relapse and lessen TRM will be needed to improve the survival of patients with t-AML and t-MDS after allogeneic HCT.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U01HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; contract HHSH234200637015C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); 2 grants, N00014-06-1-0704 and N00014-08-1-0058, from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from AABB, Aetna, American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Amgen Inc, anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin, Astellas Pharma US Inc, Baxter International Inc, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Be the Match Foundation, Biogen IDEC, BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc, Biovitrum AB, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, Bone Marrow Foundation, Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group, CaridianBCT, Celgene Corporation, CellGenix GmbH, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Children's Leukemia Research Association, ClinImmune Labs, CTI Clinical Trial and Consulting Services, Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Cylex Inc, CytoTherm, DOR BioPharma Inc, Dynal Biotech (an Invitrogen Company), Eisai Inc, Enzon Pharmaceuticals Inc, European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Gamida Cell Ltd, GE Healthcare, Genentech Inc, Genzyme Corporation, Histogenetics Inc, HKS Medical Information Systems, Hospira Inc, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Kiadis Pharma, Kirin Brewery Co Ltd, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Merck & Company, The Medical College of Wisconsin, MGI Pharma Inc, Michigan Community Blood Centers, Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc, Miller Pharmacal Group, Milliman USA Inc, Miltenyi Biotec Inc, National Marrow Donor Program, Nature Publishing Group, New York Blood Center, Novartis Oncology, Oncology Nursing Society, Osiris Therapeutics Inc, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc, Pall Life Sciences, Pfizer Inc, Saladax Biomedical Inc, Schering Corporation, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, StemCyte Inc, StemSoft Software Inc, Sysmex America Inc, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, THERAKOS Inc, Thermogenesis Corporation, Vidacare Corporation, Vion Pharmaceuticals Inc, ViraCor Laboratories, ViroPharma Inc, and Wellpoint Inc.

The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the US government.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: M.R.L. and D.J.W. designed the study; S.T., W.S.P., and J.D.R. performed the statistical analysis; M.R.L., W.S.P., and D.J.W. prepared the paper; and B.J.B., M.S.C., B.M.C., C.S.C., M.d.L., J.F.D., R.P.G., A.K., H.M.L., S.L., D.I.M., R.T.M., P.L.M., M.C.P., G.L.P., J.S., and M.S.T. participated in interpretation of data and approval of the final paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel J. Weisdorf, Adult Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, University of Minnesota Medical Center, MMC 480, 516 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN, 55455; e-mail: weisd001@umn.edu.