Abstract

Growth factor independence-1B (Gfi-1B) is a transcriptional repressor essential for erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis. Targeted gene disruption of GFI1B in mice leads to embryonic lethality resulting from failure to produce definitive erythrocytes, hindering the study of Gfi-1B function in adult hematopoiesis. We here show that, in humans, Gfi-1B controls the development of erythrocytes and megakaryocytes by regulating the proliferation and differentiation of bipotent erythro-megakaryocytic progenitors. We further identify in this cell population the type III transforming growth factor-β receptor gene, TGFBR3, as a direct target of Gfi-1B. Knockdown of Gfi-1B results in altered transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling as shown by the increase in Smad2 phosphorylation and its inability to associate to the transcription intermediary factor 1-γ (TIF1-γ). Because the Smad2/TIF1-γ complex is known to specifically regulate erythroid differentiation, we propose that, by repressing TGF-β type III receptor (TβRΙII) expression, Gfi-1B favors the Smad2/TIF1-γ interaction downstream of TGF-β signaling, allowing immature progenitors to differentiate toward the erythroid lineage.

Introduction

Growth factor independence-1 (Gfi-1) and -1B (Gfi-1B) are homologous transcriptional repressors.1 They share highly conserved Snail/Gfi1 (Snag) domain at their N-termini and 6 zinc finger domains at their C-termini.2 They bind to the same consensus sequence TAAATCAC(A/T)GCA,2-4 and are both important regulators of hematopoiesis,5-7 even though they are differentially expressed in the various hematopoietic cell populations. Gfi-1 and Gfi-1B expression are mutually exclusive.8 Whereas Gfi-1 is expressed in cells of the immune system, early B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes,2,9 monocytes, and granulocytes,6,10,11 Gfi-1B is rather found in erythroid and megakaryocytic cells.12,13 Using Gfi-1B:green fluorescent protein (GFP) knock-in mice,14 it was highlighted that its expression is highly dynamic during erythropoiesis. We12,15 and others13 have followed Gfi-1B expression in an ex vivo model of human erythropoiesis. Gfi-1B expression was higher as the number of erythroblasts increased during the culture of human CD34+ progenitors with erythropoietin (EPO) and remained sustained at the terminal differentiation stages. Recently, chromatin regulatory proteins (lysine-specific demethylase 1 [LSD1], co-RE1-silencing transcription factor [CoREST], and histone deacetylase) have been suggested to mediate transcriptional repression of Gfi-1B and its target genes.16

Inactivation of the GFI1B gene leads to embryonic lethality at day 15, as the result of arrest of erythroid maturation and failure to produce definitive enucleated erythrocytes.7 Examination of the blood from GFI1B−/− embryos revealed an abnormal primitive erythropoiesis, and flow cytometry of E12.5 fetal liver cells showed an increase in the c-kit+, ter119+ cell population. It was concluded from this study that GFI1B deficiency induces a developmental arrest of erythroid progenitors in the fetal liver at the burst-forming unit erythroid (BFU-E) stage or earlier.

Although erythropoietin (EPO) is the main erythropoiesis-regulating growth factor, other cytokines play an important role in this developmental process. Among them is transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which is recognized by hematopoietic cells through 3 cell-surface receptors, namely, TGF-β type I, II, and III receptors (TβRI, TβRII, and TβRIII), all displaying different affinities for their ligand.17 In contrast to TβRI and TβRII, TβRIII is a membrane-anchored proteoglycan that does not possess an intrinsic kinase activity but enhances TβRI- and TβRII-mediated signaling by stabilizing their complex with TGF-β,18 regulating TGF-β receptor complex formation19 and internalization,20,21 and/or induces Smad-independent signaling.22-24 Its importance is emphasized by the fact that TGFBR3 knockout mice lead to embryonic lethality at day 16 resulting from liver and heart developmental defects, but their phenotype in terms of erythroid development remains unexplored.25,26 However, it has been shown that, in immature adult hematopoietic progenitor cells, phospho-Smad2/3 associates with either Smad4 to inhibit progenitor proliferation or with TIF1-γ to promote erythroid differentiation.27

In this report, we explore the function of Gfi-1B in primary human and immature adult progenitor cells. Using shRNA-mediated silencing, we show that Gfi-1B controls the development of erythroid cells and megakaryocytes at the bipotent erythro-megakaryocytic progenitor (MEP) stage. We further identified the TGFBR3 gene that encodes TβRIII, as a target for Gfi-1B in the MEP cell population and showed that Gfi-1B specifically binds to and represses the activity of the TGFBR3 gene promoter. Consistent with these findings, Gfi-1B depletion alters TGF-β signaling by compromising the formation of the phospho-Smad2/TIF1-γ complex that is required for erythroid differentiation. These data propose that Gfi-1B controls erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis at least in part by regulating TGFBR3 expression in MEP.

Methods

Cell culture and colony-forming unit assays

Human HEK293 and K562 cell lines were expanded in Dulbecco minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2mM l-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin.

Human umbilical cord blood samples were collected from normal full-term deliveries, after informed consent of the mothers, according to the approved institutional guidelines of Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris. After a Ficoll-metrizoate gradient separation (Biochrom), CD34+ cells were enriched by an immunomagnetic selection (Miltenyi Biotec, purity ≥ 95%) and cultured for 4 to 5 days in Stem Span H3000 medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 50 ng/mL human stem cell factor (SCF), 100 ng/mL Flt3-ligand (FL), 60 ng/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3), and 20 ng/mL thrombopoietin (TPO; Promocell Bioscience). For erythroid differentiation, CD34+ cells were grown in Stem Span H3000 medium containing 25 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6 (Promocell Bioscience), and 2 IU/mL EPO (a gift from Dr Brandt, Roche Diagnostics). For megakaryocytic differentiation, cells were cultured in medium containing 5 ng/mL SCF and 10 ng/mL TPO. Myeloid and megakaryocytic colony assays were performed as described.15

Cell-cycle and apoptosis assay

For cell-cycle analysis, sorted CD34+ GFP+ cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 70% ethanol for 1 hour at −20°C, and then labeled with 1 mg/mL propidium iodide in the presence of 20 μL of RNAse at 10 mg/mL for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cell cycle–oriented histogram analysis was performed using FlowJo software. Phosphatidylserine exposure was measured by annexin V binding. Cells were incubated with 1 μg of phycoerythrin (PE)-coupled annexin V and 2 μL per 104 cells viability dye 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) for 15 minutes at 37°C in 50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.4), 140mM NaCl, 1mM CaCl2 buffer. The proportion of the cells in different quadrants was determined.

shRNA mediated-silencing and cell transduction

Three lentiviral vectors containing Gfi-1B shRNA were used (supplemental data, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The specific TβRIII shRNA was from Sigma-Aldrich (pLK0.1 TGFBR3 RNAi), and the shRNA control with a random sequence was generously given by Goardon et al.28 Recombinant lentiviruses were produced as previously described.12

Western blotting

Protein extracts were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell), and immunoblotted with the appropriate antibody. The primary antibodies were specific of human Gfi-1, TβRI, TβRII, Smad2/3 and Smad4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TβRIII (R&D Systems), High-Mobility Group Box protein HMGB2 (BD Biosciences PharMingen), phospho-Smad2 (Cell Signaling), p21cip/waf1 (Oncogene Research Products), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), TIF1-γ,27 and Gfi-1B, an antibody that was prepared in our laboratory.15 The peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were specific of goat (Southern Biotechnology), mouse, or rabbit immunoglobulins (IgGs; Cell Signaling Technology).

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Cell immunostaining was performed with PE-conjugated antihuman CD34 antibody, allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD36, and PE-conjugated antiglycophorin A (GPA) antibodies (Caltag Laboratories). Dead cells were excluded by propidium iodide staining. Appropriate isotype-matched controls were used to determine the background staining level. Cells were analyzed using FACSCalibur analyzer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems).

Common myeloid progenitor (CMP), granulo-macrophagic progenitor (GMP), and MEP populations were sorted on FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences) after PE.Cy5.5-coupled anti-CD34 (Caltag), biotinylated anti-CD38 (BioLegend) revealed by Pacific orange-conjugated streptavidin, PE-coupled anti-CD123 (BioLegend), and allophycocyanin-coupled anti-CD45RA (Caltag) labeling.

RT-PCR and microarray analysis

Extraction and reverse transcription (RT) of total RNA were performed as described.15 cDNA was amplified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using human TβRI, II, III, Gfi-1B, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) specific primers (supplemental data) according to the described thermal cycling program.15 The fold-change expression of each gene is represented by the ratio between the copy number of tested cDNA and the GAPDH cDNA calculated with the curve obtained with serial dilution of control cDNA.

Affymetrix analyses were performed with purified total RNA from shControl- and shGfi-1B-infected CD34+ cells and MEP. Gene expression profiling of each population was determined by hybridization on Affymetrix microarrays (Gene Chip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 array). The microarray dataset was deposited at ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress; array accession no. E-MEXP-2560).

Transcription reporter luciferase assays

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as described15 using plasmids containing the reporter luciferase gene under proximal TGFBR3 promoters29 with or without Gfi-1B expression plasmid. pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase, Promega) and pGL2-luciferase were used as an internal control to correct transfection efficiency.

Oligonucleotide pull-down and immunoprecipitation assays

Oligonucleotide pull-down assays were performed as described15 with increasing amounts of wild-type or mutated double-strand biotin-labeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the TGFBR3 proximal promoter (supplemental data).

For immunoprecipitation assays, nuclear extracts from 107 cells were precleared by addition of 2 μg of normal IgG for 2 hours. After incubation with 50 μL of protein G beads (GE Healthcare) and centrifugation, 2 μg of human Smad2/3 antibody or control IgG was added on the supernatant. The following day, 50 μL of protein G beads was added and protein complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting.

ChIP assays

K562 cells were fixed, lysed, and sonicated as described.15 Immunoprecipitations were performed following the Upstate protocol (www.upstate.com) using a human Gfi-1B antibody (from our laboratory) and control rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). PCR was performed on immunoprecipitated DNA as described15 using specific primers of TGFBR3 proximal promoter and a control region located upstream of the promoter (supplemental data).

Results

Gfi-1B knockdown alters the proliferation of CD34+ cells

Inactivation of GFI1B in mice leads to embryonic lethality, impeding the use of these knockout mice to study the role of Gfi-1B on adult hematopoiesis. We thus used shRNA-containing lentiviral vectors to down-regulate Gfi-1B expression in human primary immature progenitors. Amplified infected CD34+ cells were plated in erythroid (E0-E7) or megakaryocytic (T0-T10) liquid culture conditions and analyzed for the expression of Gfi-1, Gfi-1B, and p21 various days after infection. We observed that Gfi-1B was efficiently knocked down at all differentiation stages (from E0 to E6 and from T0 to T4, the result of one shRNA is shown), validating our experimental system to study the role of Gfi-1B in human adult erythropoiesis (Figure 1E). Interestingly, contrary to what was observed in control cells, Gfi-1 expression remained elevated during erythroid and megakaryocytic development of shGfi-1B–transduced cells, whereas Gfi-1B expression decreased in agreement with a recent report showing that Gfi-1B represses Gfi-1 transcription in erythroid and megakaryocytic cells.8 Furthermore, it is interesting to note that p21 expression was up-regulated in the absence of Gfi-1B. We thus evaluate the role of Gfi-1B in CD34+ cell proliferation by infecting them twice with lentiviruses carrying an shControl or shGfi-1B. Forty-eight hours after the second infection, CD34+ and GFP+ cells were sorted, cultured in the same amplification culture medium, and tested for their ability to grow in the same previous culture medium (D5-D9) (Figure 1A). Gfi-1B knockdown decreased the proliferation of immature CD34+ progenitor cells (Figure 1B). No apoptosis was observed in the cultures (Figure 1C). The proportion of the cells in G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle was more important at day 9 in Gfi-1B knockdown cells compared with control cells (Figure 1D). Equivalent results were obtained with 2 other Gfi-1B shRNA sequences (data not shown). Thus, in the absence of Gfi-1B, immature progenitors have a reduced cell growth.

Gfi-1B knockdown impairs proliferation in primary human immature progenitor cells. (A) Experimental protocol to test the effects of Gfi-1B knockdown in immature primary human progenitors. CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood and amplified for 24 hours in the presence of IL-3, SCF, TPO, and FL and then infected with lentiviruses carrying shControl or shGfi-1B. Forty-eight hours after infection (D4), CD34+GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured in liquid culture in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and EPO to induce the erythroid (E0-E7) or SCF and TPO for megakaryocytic differentiation (T0-T10). (B) Proliferation of shControl or shGfi-1B CD34+ cells. After CD34+GFP+ sorting, cells were cultured in the presence of SCF, FL, IL-3, and TPO and counted every day (corresponding to D5-D9 in the experimental protocol described in panel A) in the presence of Trypan blue. Error bars represent SD; n = 4 from different samples. (C-D) Flow cytometry histograms after annexin V and 7-AAD staining (C) and proportion of the cells in different phase of the cell cycle after 7-AAD and propidium iodide staining (D). Infected shControl and shGfi-1B CD34+ cells were analyzed at D5 and D7 or D9. (E) ShGfi-1B efficiency during erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. Cell lysates (noninfected cells [NI] and shControl or shGfi-1B for infected cells) were prepared at different times after induction of erythroid (E3 and E6) or megakaryocytic differentiation (T3 and T4) and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against Gfi-1B, Gfi-1, p21cip/waf1, or β-actin (as control). The membrane was highly exposed after hybridization with Gfi-1B antibody to determine the efficiency of the Gfi-1B shRNA.

Gfi-1B knockdown impairs proliferation in primary human immature progenitor cells. (A) Experimental protocol to test the effects of Gfi-1B knockdown in immature primary human progenitors. CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood and amplified for 24 hours in the presence of IL-3, SCF, TPO, and FL and then infected with lentiviruses carrying shControl or shGfi-1B. Forty-eight hours after infection (D4), CD34+GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured in liquid culture in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and EPO to induce the erythroid (E0-E7) or SCF and TPO for megakaryocytic differentiation (T0-T10). (B) Proliferation of shControl or shGfi-1B CD34+ cells. After CD34+GFP+ sorting, cells were cultured in the presence of SCF, FL, IL-3, and TPO and counted every day (corresponding to D5-D9 in the experimental protocol described in panel A) in the presence of Trypan blue. Error bars represent SD; n = 4 from different samples. (C-D) Flow cytometry histograms after annexin V and 7-AAD staining (C) and proportion of the cells in different phase of the cell cycle after 7-AAD and propidium iodide staining (D). Infected shControl and shGfi-1B CD34+ cells were analyzed at D5 and D7 or D9. (E) ShGfi-1B efficiency during erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. Cell lysates (noninfected cells [NI] and shControl or shGfi-1B for infected cells) were prepared at different times after induction of erythroid (E3 and E6) or megakaryocytic differentiation (T3 and T4) and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against Gfi-1B, Gfi-1, p21cip/waf1, or β-actin (as control). The membrane was highly exposed after hybridization with Gfi-1B antibody to determine the efficiency of the Gfi-1B shRNA.

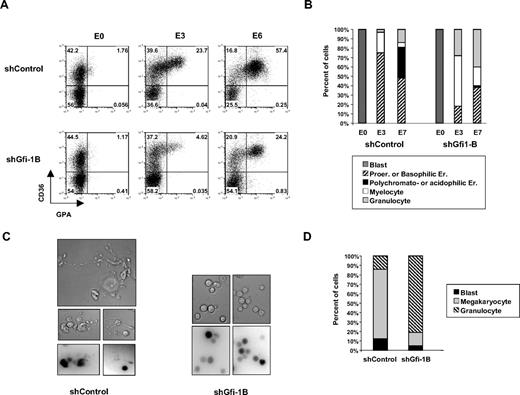

Gfi-1B knockdown affects terminal erythroid and megakaryocyte differentiation

To determine whether Gfi-1B is indispensable for terminal erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation, CD34 cells were plated in the presence of EPO, IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (E0-E7) to induce erythroid differentiation, or in the presence of TPO and SCF (T0-T10) to induce megakaryocytic differentiation. We observed by cytofluorometry that the proportion of CD36+GPA+ cells, which increased on EPO stimulation in control transduced cells (from 1.8% to 57.4%), did not show such an important increase in shGfi-1B–transduced cells (from 1.2% to 24.2%) (Figure 2A). In agreement with this result, cytology performed on May-Grunwald-Giemsa–stained cytospins showed that, 7 days on induction of differentiation, the percentage of immature erythroblasts (ER; pro- and basophilic; 64.1 ± 15 vs 13.0 ± 7.1, mean ± SD, n = 4) as well as the percentage of differentiated erythroblasts (polychromatophilic and acidophilic Er; 22.0% ± 15.5% vs 1.5% ± 0.7%, mean ± SD, n = 4) were decreased in Gfi-1B–depleted cells (Figure 2B). Similarly, after 10 days of culture in the presence of TPO, shGfi-1B cells gave rise to decreased amounts of megakaryocytes than shControl cells (72% vs 14%; Figure 2D). Accordingly, shGfi-1B–transduced megakaryocytes did not display proplatelet-like protrusions compared with shControl-transduced cells (Figure 2C). Equivalent results were obtained with the 2 other Gfi-1B shRNA (supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, although Gfi-1B depletion led to an increase of Gfi-1 expression in erythroid and megakaryocytic cells (Figure 1E), such increase was not sufficient to drive normal erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis. We conclude that Gfi-1B affects proliferation in immature progenitor cells and is specifically required for terminal human erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation.

Terminal erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. (A-B) Analysis of erythroid differentiation. CD36 and GPA expression was analyzed by flow cytometry before (E0) and 3 days (E3) or 6 days (E6) after induction of erythroid differentiation of shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced cells. Numbers in plots indicate percentage of cells within each quadrant (A). Cytology of the same cells was analyzed after May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining (B). (C-D) Analysis of megakaryocytic differentiation. Infected cells cultured in the presence of TPO and SCF were observed (C) under an Eclipse TE3200 inverted microscope (Nikon) with a 40× oil objective. Images were collected with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (CoolSNAPfx; Roper Scientific) and the Metavue Imaging system (Universal Imaging) and then analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), and mature megakaryocytes were counted after May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining (D). All these results are representative of more than 4 independent experiments.

Terminal erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. (A-B) Analysis of erythroid differentiation. CD36 and GPA expression was analyzed by flow cytometry before (E0) and 3 days (E3) or 6 days (E6) after induction of erythroid differentiation of shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced cells. Numbers in plots indicate percentage of cells within each quadrant (A). Cytology of the same cells was analyzed after May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining (B). (C-D) Analysis of megakaryocytic differentiation. Infected cells cultured in the presence of TPO and SCF were observed (C) under an Eclipse TE3200 inverted microscope (Nikon) with a 40× oil objective. Images were collected with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (CoolSNAPfx; Roper Scientific) and the Metavue Imaging system (Universal Imaging) and then analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), and mature megakaryocytes were counted after May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining (D). All these results are representative of more than 4 independent experiments.

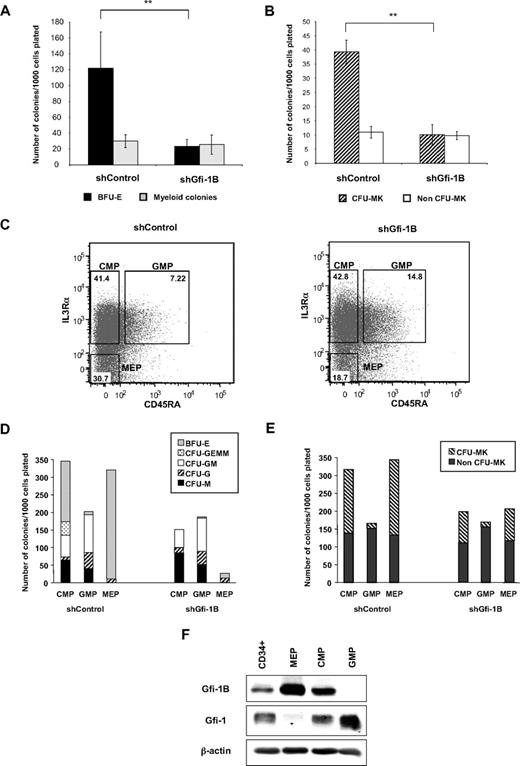

Gfi-1B knockdown impairs the differentiation of megakaryocytic and erythroid progenitors

We next studied the effect of Gfi-1B knockdown on the different progenitor compartments to investigate whether the requirement of Gfi-1B for terminal erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation results from its function in immature progenitors. For this, 2 to 3 days on transduction, the CD34+GFP+ cell population was cultured in a semisolid medium to allow progenitor development. A drastic decrease in the BFU-E number was observed when plating shGfi-1B-transduced cells in methylcellulose compared with shControl-transduced cells (23.5 ± 8 vs 122.0 ± 45, n = 8; Figure 3A). Similarly, shGfi-1B cells plated in semisolid medium with megakaryocytic cytokines gave rise to very few colony-forming units-megakaryocyte (CFU-MK) containing CD41+ cells, compared with control cells (10.1 ± 2 CFU-MK vs 39.3 ± 4, n = 6; Figure 3B). Importantly, no difference was observed in the number of granulo-macrophagic colonies generated from the Gfi-1B knocked down population, progenitors that are known to not rely on Gfi-1B for their differentiation (Figure 3A). Importantly, the same decrease in erythroid and megakaryocytic progenitors was observed with the 2 other Gfi-1B shRNA (supplemental Table 1). Hence, Gfi-1B knockdown leads to a decrease in the amount of erythroid and megakaryocytic colonies derived from BFU-E and CFU-MK.

The MEP compartment is reduced in the absence of Gfi-1B. (A-B) Erythroid and megakaryocytic colony formation in semisolid medium. At 48 hours after retroviral infection, before induction of erythroid differentiation (E0), infected CD34+GFP+ cell populations were plated in Methocult in the presence of EPO, IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (A) or in Megacult in the presence of TPO, IL-6, and IL-3 (B). Results are from 6 independent experiments and are mean ± SD. **P < .001. (C) Comparison of the size of the 3 progenitor populations from shControl- or shGfi-1B–infected cells. CD38+CD34+GFP+ cells were separated according to their CD123 and CD45RA expression. Percentage of cells in the 3 populations was indicated in the gates. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D-E) Colony readout of sorted cells from transduced cells (gates described in panel C) in Methocult (D) or in Megacult (E). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Gfi-1B and Gfi-1 expression in CD34+, CMP, GMP, and MEP populations. Total nuclear extracts were prepared from cells of each population and analyzed by immunobloting using antibodies recognizing Gfi-1B, Gfi-1, and β-actin (as control to confirm equal protein loading).

The MEP compartment is reduced in the absence of Gfi-1B. (A-B) Erythroid and megakaryocytic colony formation in semisolid medium. At 48 hours after retroviral infection, before induction of erythroid differentiation (E0), infected CD34+GFP+ cell populations were plated in Methocult in the presence of EPO, IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (A) or in Megacult in the presence of TPO, IL-6, and IL-3 (B). Results are from 6 independent experiments and are mean ± SD. **P < .001. (C) Comparison of the size of the 3 progenitor populations from shControl- or shGfi-1B–infected cells. CD38+CD34+GFP+ cells were separated according to their CD123 and CD45RA expression. Percentage of cells in the 3 populations was indicated in the gates. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D-E) Colony readout of sorted cells from transduced cells (gates described in panel C) in Methocult (D) or in Megacult (E). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Gfi-1B and Gfi-1 expression in CD34+, CMP, GMP, and MEP populations. Total nuclear extracts were prepared from cells of each population and analyzed by immunobloting using antibodies recognizing Gfi-1B, Gfi-1, and β-actin (as control to confirm equal protein loading).

Importantly, such results do not formally demonstrate whether Gfi-1B is indeed required at the progenitor stage because a blockade in late differentiation would prevent colony formation and, thus, BFU-E and CFU-MK colony detection. To circumvent this problem, we thus evaluated by flow cytometry the size of the 3 progenitor compartments: CMP (CD123lowCD45RA−), GMP (CD123lowCD45RA+), and MEP (CD123−CD45RA−).30 We observed that, whereas the proportion of CMP slightly increased in the absence of Gfi-1B (41.4% vs 42.8%), the percentage of GMP increased (7.2% vs 14.8%) and the percentage of MEP decreased (30.7% vs 18.7%; Figure 3C). Although these populations were not cell homogeneous, this result can be interpreted in 2 ways: Gfi-1B deficiency (1) favors the commitment of CMP toward the granulo-macrophagic lineage or (2) impedes erythroid development, implying that the increase in the percentage of GMP is the result of the decrease in the percentage of MEP. To distinguish between these 2 possibilities, we determined the number of progenitors present in the sorted shControl- or shGfi-1B–infected CMP, GMP, and MEP cell populations (Figure 3D-E). Both shControl and shGfi-1B GMP populations gave rise to similar numbers of G-, GM-, and M-CFC colonies (Figure 3D). In contrast, decreased BFU-E and CFU-MK were generated from both shGfi-1B CMP and MEP populations, highlighting the differences in the erythroid and megakaryocytic potential of Gfi-1B–sufficient and –deficient cells (Figure 3D-E). Importantly, introduction of a mouse Gfi-1B in Gfi-1B knockdown CD34+ cells restored the cellular phenotype at the progenitor and differentiated stages (supplemental Figure 2). We conclude that Gfi-1B is not involved in the commitment of CMP toward erythro-megakaryocytic or granulo-macrophagic development but controls the size and differentiation of the MEP population.

In agreement with this result, we found that Gfi-1B was highly expressed in the MEP population, whereas it was expressed at low level in CMP and not expressed in GMP (Figure 3F). Gfi-1B was barely detected in the CD34+ cell population that is heterogeneous and contains the 3 CMP, GMP, and MEP cell populations. In contrast, Gfi-1 was poorly expressed in MEP and highly expressed in CMP and GMP, confirming results obtained by others in mice.14 Thus, among progenitors, MEP express the highest amount of Gfi-1B and their number is altered in the absence of Gfi-1B, strongly suggesting that Gfi-1B plays a key role in the maintenance and development of these progenitor cells.

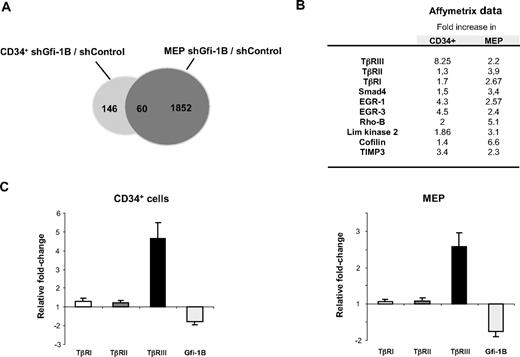

Gfi-1B controls TβRIII expression in both CD34+ cells and bipotent MEPs

Having shown that the transcription repressor Gfi-1B regulates the size and differentiation of the MEP compartment, we next aimed at identifying its target genes in this cell population. We used microarrays (Affymetrix 20.1) to compare the transcriptome of MEP or CD34+ cells infected with lentiviruses carrying either the shGfi-1B or the shControl. We found that only 146 genes were up-regulated in shGfi-1B CD34+ cells compared with shControl CD34+ cells. In contrast, 1852 genes are up-regulated in shGfi-1B MEP compared with their shControl counterpart, in agreement with their high Gfi-1B expression level and the highest homogeneity of the cell population (Figure 4A). Among these genes, 60 were found to be up-regulated in both Gfi-1B–depleted CD34+ and MEP populations by comparison of Affymetrix data. Interestingly, this group of 60 genes included several genes encoding proteins involved in TGF-β signaling (Figure 4B). In particular, the expression of the type III TGF-β receptor (TβRIII or betaglycan) was up-regulated in CD34+ and MEP populations lacking Gfi-1B, suggesting that Gfi-1B represses the transcription of this gene in immature progenitors.

TβRIII mRNA accumulates in CD34+ cells and in MEP in the absence of Gfi-1B. (A) Venn diagram showing the number of differentially expressed genes after Gfi-1B knockdown in CD34+ cells or MEP. shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced cells were harvested 48 hours after retroviral infection, and mRNA were hybridized on Affymetrix microarrays. The number of genes differentially expressed as well as the number of genes that were up-regulated in both cell populations were indicated in the corresponding region of the diagram. (B) A subset of proteins involved in TGF-β signaling, which are up-regulated in both CD34+ and MEP after Gfi-1B depletion. The values represent Affymetrix data showing the fold increase between control and Gfi-1B knockdown cells. (C) Comparison of the mRNA expression of the 3 TGF-β receptors (TβRI, II, and III) in shControl- and shGfi-1B–transduced CD34+ or MEP. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using TβRI, II, and III and Gfi-1B–specific primers. Data are expressed as fold change from controls, with GAPDH primers used as an internal control. Error bars represent SD of 4 experiments.

TβRIII mRNA accumulates in CD34+ cells and in MEP in the absence of Gfi-1B. (A) Venn diagram showing the number of differentially expressed genes after Gfi-1B knockdown in CD34+ cells or MEP. shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced cells were harvested 48 hours after retroviral infection, and mRNA were hybridized on Affymetrix microarrays. The number of genes differentially expressed as well as the number of genes that were up-regulated in both cell populations were indicated in the corresponding region of the diagram. (B) A subset of proteins involved in TGF-β signaling, which are up-regulated in both CD34+ and MEP after Gfi-1B depletion. The values represent Affymetrix data showing the fold increase between control and Gfi-1B knockdown cells. (C) Comparison of the mRNA expression of the 3 TGF-β receptors (TβRI, II, and III) in shControl- and shGfi-1B–transduced CD34+ or MEP. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using TβRI, II, and III and Gfi-1B–specific primers. Data are expressed as fold change from controls, with GAPDH primers used as an internal control. Error bars represent SD of 4 experiments.

To verify these Affymetrix data, we prepared mRNA from shControl- and shGfi-1B–transduced MEP and CD34+ cells and analyzed, by quantitative RT-PCR, the presence of the 3 TGF-β receptor transcripts. We reproducibly observed that Gfi-1B knockdown led to a strong up-regulation in the levels of TβRIII mRNA in both CD34+ cells (4.6- ± 0.9-fold increase) and MEP (2.6- ± 0.4-fold increase), whereas the levels of TβRI and TβRII transcripts were barely modified at the mRNA (Figure 4C) and protein levels (supplemental Figure 1). We conclude that Gfi-1B negatively regulates the transcription of the TGFBR3 gene in human primary erythroid and megakaryocytic progenitors.

Gfi-1B binds to the TGFBR3 promoter in MEPs and represses its activity

To investigate whether Gfi-1B–dependent transcriptional repression of TGFBR3 is direct or not, we assessed the ability of Gfi-1B to bind to and to regulate the activity of the TGFBR3 promoter. To do so, we switched to K562 cells, which represent a valuable cell line model for immature MEPs31 and which respond to TGF-β by concomitant induction of hemoglobin and reduction in cell proliferation.32 Accordingly, as observed in CD34+ cells and MEP population, TβRIII expression was increased at both the mRNA and protein levels in shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells (Figure 5A-B), whereas the protein expression of TβRI and TβRII remained unchanged (Figure 5B). Two important regulatory regions have been described in the TGFBR3 promoter29 : (1) the proximal region and (2) the distal region, located at 25 kb and 45 kb from the translation initiation codon, respectively (Figure 5C). To investigate the regulation of the TGFBR3 promoter activity by Gfi-1B in the regulation of TGFBR3 transcription, we transfected the wild-type distal or the wild-type proximal promoter luciferase constructs into HEK293 cells together with or without a Gfi-1B expression plasmid. Gfi-1B expression reduced the activity of the proximal TGFBR3 promoter by 45% (Figure 5D) but had no effect on the activity of the distal one (data not shown). Sequence analysis identified 4 motifs AATC/GATT in the proximal promoter sequence (−525, −474, −134, and −55). To define the role of the different Gfi-1B putative binding sites in the proximal region of the TGFBR3 promoter, we transfected plasmids in which −165/+60 or −75/+60 region was cloned upstream of the luciferase gene.29 Gfi-1B induced a significant reduction of luciferase activity when luciferase gene expression was driven by the −559/+60 and −165/+60 TGFBR3 promoters but not when using the −75/+60 promoter. These results indicate that the −134 Gfi-1B binding site, which is very well conserved through species (data not shown), plays an important role in the transcriptional repression of the TGFBR3 promoter by Gfi-1B. We conclude that Gfi-1B can repress the activity of the TGFBR3 promoter by acting on its proximal regulatory element.

TGFBR3 is a target gene of Gfi-1B in MEP cells. (A-B) TGF-β receptor expression at the mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels in shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells. Data are expressed as the ratio between TβRIII and GAPDH mRNA; error bars represent SD of 2 experiments (A). Proteins were analyzed by Western blot with antibodies indicated on the left in panel B. (C) Schematic representation of the TGFBR3 promoter. Distal and proximal regions were shown. (D) TGFBR3 promoter activity in the absence or presence of Gfi-1B expression plasmid. Transient transfections were performed into HEK293 cells. The proximal region of the TGFBR3 promoter cloned in front of luciferase gene reporter was transfected without or with 2 different doses (125 or 250 ng) of Gfi-1B expression vectors as indicated. Luciferase activity was measured 48 hours after transfection. Results are mean ± SD of 4 experiments (x on the TGFBR3 promoter indicates AATC/GATT sequence). ***P < .001, *P = .05 determined by Student t test. (E) Gfi-1B binding to the TGFBR3 promoter. Oligo-pull down experiments were performed using K562 cell extracts and increasing concentrations of oligonucleotides corresponding to a sequence surrounding the −134 Gfi-1B binding site of the wild-type TGFBR3 proximal promoter. GATT was mutated in GACC as indicated by a cross. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. The membrane was hybridized with HMGB2 antibody to quantify the loading and to show the specificity of the Gfi-1B binding to this region of the TGFBR3 promoter. (F) Gfi-1B binding to the TGFBR3 promoters in vivo. ChIP analyses were performed with chromatin from undifferentiated shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells using antibodies against Gfi-1B. Quantitative PCR was performed with primers amplifying the TGFBR3 promoter. Results are fold increase (mean ± SD) of 3 independent ChIP experiments. *P < .02 determined by Student t test.

TGFBR3 is a target gene of Gfi-1B in MEP cells. (A-B) TGF-β receptor expression at the mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels in shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells. Data are expressed as the ratio between TβRIII and GAPDH mRNA; error bars represent SD of 2 experiments (A). Proteins were analyzed by Western blot with antibodies indicated on the left in panel B. (C) Schematic representation of the TGFBR3 promoter. Distal and proximal regions were shown. (D) TGFBR3 promoter activity in the absence or presence of Gfi-1B expression plasmid. Transient transfections were performed into HEK293 cells. The proximal region of the TGFBR3 promoter cloned in front of luciferase gene reporter was transfected without or with 2 different doses (125 or 250 ng) of Gfi-1B expression vectors as indicated. Luciferase activity was measured 48 hours after transfection. Results are mean ± SD of 4 experiments (x on the TGFBR3 promoter indicates AATC/GATT sequence). ***P < .001, *P = .05 determined by Student t test. (E) Gfi-1B binding to the TGFBR3 promoter. Oligo-pull down experiments were performed using K562 cell extracts and increasing concentrations of oligonucleotides corresponding to a sequence surrounding the −134 Gfi-1B binding site of the wild-type TGFBR3 proximal promoter. GATT was mutated in GACC as indicated by a cross. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. The membrane was hybridized with HMGB2 antibody to quantify the loading and to show the specificity of the Gfi-1B binding to this region of the TGFBR3 promoter. (F) Gfi-1B binding to the TGFBR3 promoters in vivo. ChIP analyses were performed with chromatin from undifferentiated shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells using antibodies against Gfi-1B. Quantitative PCR was performed with primers amplifying the TGFBR3 promoter. Results are fold increase (mean ± SD) of 3 independent ChIP experiments. *P < .02 determined by Student t test.

We next verified whether Gfi-1B binds to the proximal region of the TGFBR3 promoter in K562 cells by performing DNA affinity precipitation experiments. We thus used biotinylated oligonucleotides representing the wild-type or mutated region of the TGFBR3 promoter that enclosed the −134 binding site (Figure 5E). Strikingly, we found that Gfi-1B binds in a dose-dependent manner to the wild-type oligonucleotide corresponding to the proximal TGFBR3 promoter sequence, whereas no binding was detected when using the oligonucleotide mutated at the Gfi-1B consensus binding site (Figure 5E). This result and the fact that 2 different groups3,4 characterized by the random oligonucleotide binding-selection strategy the Gfi-1B binding site as being AATC (or GATT) in 100% of the cases strongly suggest that GATT is a nondegenerated Gfi-1B consensus-binding site. Because Gfi-1 is not expressed in K562, we did not find Gfi-1 binding to these oligonucleotides. We conclude that, in vitro, Gfi-1B binds to the proximal TGFBR3 promoter.

To verify these results in vivo, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments in shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated using antibodies directed against Gfi-1B or control IgG. Primers amplifying a specific region of the TGFBR3 promoter (−0.15 kb) or a region located upstream of the promoter (−2.3 kb) were used. The result showed that Gfi-1B binds to the TGFBR3 proximal promoter (Figure 5F). This interaction was specific as shown by a significant binding decrease in Gfi-1B knocked down cells (n = 3, P < .001). No enrichment was found on the region located upstream the promoter (−2.3 kb). Hence, the TGFBR3 promoter is a target for Gfi-1B–mediated transcriptional repression in bipotent MEP cells.

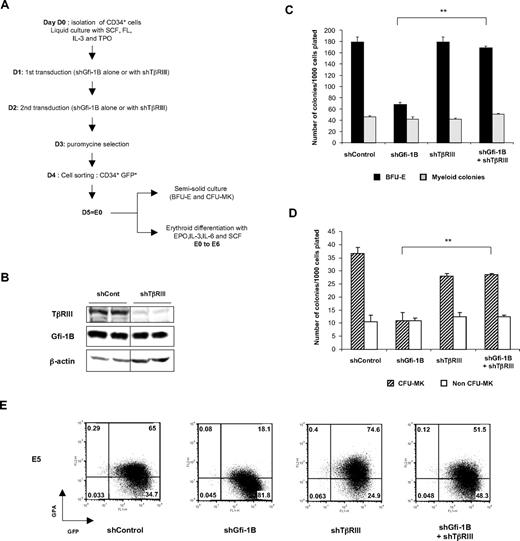

Reconstitution of erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation on decrease of TGFBRIII in Gfi-1B–depleted cells

To establish whether increase TGFBRIII expression is responsible for the suppressed erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation in Gfi-1B knockdown cells, we performed rescue experiments using lentiviral vectors carrying an shRNA against TβRIII in Gfi-1B–depleted CD34 cells. CD34+ cells infected with lentivirus containing a Gfi-1B shRNA (including a GFP sequence) alone or together with TβRIII shRNA (including a puromycin sequence). Infected cells were selected with puromycin, and GFP+ cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; Figure 6A). The efficiency of the TβRIII shRNA was shown on K562 cells, which expressed abundant endogenous TβRIII (Figure 6B). Whereas Gfi-1B–depleted cells gave rise to few BFU-E (68.0 ± 4) or CFU-MK (11.0 ± 3) per 1000 cells plated, cells with both Gfi-1B and TβRIII knockdown gave rise to the same numbers of progenitors as shControl-infected cells (179 ± 9 BFU-E and 36.5 ± 2.5 CFU-MK for the control and 169 ± 3 BFU-E and 28.5 ± 0.5 CFU-MK for cells depleted for both Gfi-1B and TβRIII). Interestingly, depletion of TβRIII alone did not affect erythroid and megakaryocytic progenitor development (Figure 6C-D). GPA expression analyses showed that, in the absence of both Gfi-1B and TβRIII, erythroid maturation developed normally (Figure 6E). This result was confirmed by benzidine staining: 5 days after induction of erythroid differentiation, the same percentage of benzidine-positive cells was observed in control and in shGfi-1B+ shTβRIII-transduced cells (data not shown). Thus, knockdown of TβRIII in Gfi-1B–depleted cells rescues the erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation, indicating that Gfi-1B drives erythroid and megakaryocytic development by repressing TGFBR3 transcription.

Rescue of erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation by knockdown of TGFBR3 in Gfi-1B–depleted CD34+ cells. (A) Experimental protocol to test the effects of TβRIII shRNA in Gfi-1B knockdown immature primary human progenitors. CD34+ cells were amplified for 24 hours in the presence of IL-3, SCF, TPO, and FL and then infected with lentiviral vectors carrying shControl or shGfi-1B or with both of them (shGfi-1B+shΤβRΙΙΙ). The day after the second transduction, cells were selected for puromycin resistance; and after 24 hours, GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS. Then, cells were either plated in semisolid medium to determine the number of erythroid or megakaryocytic progenitors or cultured in liquid culture in the presence of EPO and SCF. (B) TβRIII shRNA efficiency in K562 cells. K562 cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors containing the TβRIII shRNA and selected in the presence of puromycin. At 48 hours after the beginning of the selection, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis with a TβRIII-specific antibody. (C-D) Erythroid (C) and megakaryocytic (D) colony formation in semisolid medium. As described in Figure 3A, puromycin-resistant GFP+-infected cells were plated in Methocult in the presence of EPO, IL-3, IL-6, and SCF or in Megacult in the presence of TPO, IL-6, and IL-3. Error bars represent SD. **P < .002; n = 2 with different samples. (E) Analysis of erythroid differentiation. GPA expression was analyzed by flow cytofluorometry 5 days after induction of erythroid differentiation of shControl-, shGfi-1B-shTβRIII–, or shGfi-1B+shTβRIII–transduced cells.

Rescue of erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation by knockdown of TGFBR3 in Gfi-1B–depleted CD34+ cells. (A) Experimental protocol to test the effects of TβRIII shRNA in Gfi-1B knockdown immature primary human progenitors. CD34+ cells were amplified for 24 hours in the presence of IL-3, SCF, TPO, and FL and then infected with lentiviral vectors carrying shControl or shGfi-1B or with both of them (shGfi-1B+shΤβRΙΙΙ). The day after the second transduction, cells were selected for puromycin resistance; and after 24 hours, GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS. Then, cells were either plated in semisolid medium to determine the number of erythroid or megakaryocytic progenitors or cultured in liquid culture in the presence of EPO and SCF. (B) TβRIII shRNA efficiency in K562 cells. K562 cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors containing the TβRIII shRNA and selected in the presence of puromycin. At 48 hours after the beginning of the selection, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis with a TβRIII-specific antibody. (C-D) Erythroid (C) and megakaryocytic (D) colony formation in semisolid medium. As described in Figure 3A, puromycin-resistant GFP+-infected cells were plated in Methocult in the presence of EPO, IL-3, IL-6, and SCF or in Megacult in the presence of TPO, IL-6, and IL-3. Error bars represent SD. **P < .002; n = 2 with different samples. (E) Analysis of erythroid differentiation. GPA expression was analyzed by flow cytofluorometry 5 days after induction of erythroid differentiation of shControl-, shGfi-1B-shTβRIII–, or shGfi-1B+shTβRIII–transduced cells.

TGF-β signaling is altered in the absence of Gfi-1B

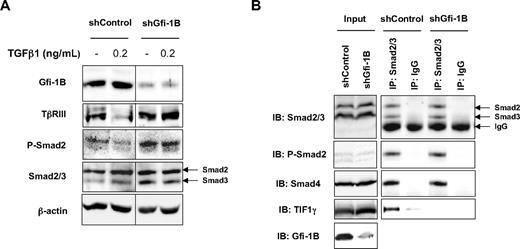

Our results show that, in the absence of Gfi-1B, TGFBR3 transcription is up-regulated in immature human MEPs. We thus hypothesized that this increase in TβRIII expression leads to altered TGF-β signaling. To address this question, we analyzed the activation of the canonical TGF-β pathway in shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells.27 Whereas K562 cells had elevated basal levels of phosphorylated Smad2, probably resulting from Brc-Abl expression, which is known to constitutively activate many signaling pathways, Gfi-1B knockdown led to a significant increase in the phosphorylation of Smad2 in immature K562 cells, which paralleled the increase in TβRIII expression (Figure 7A). Hence, TGF-β signaling is altered in MEP cells that lack Gfi-1B.

TGF-β signalization pathway is amplified and complex formation is modified in the absence of Gfi-1B. (A) Increase of Smad2 phosphorylation in the absence of Gfi-1B. shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells were stimulated or not with TGFβ1 (R&D Systems) for 1 hour. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies indicated on the left of the figure (as controls, Smad2/3 and β-actin). Three experiments with different samples were performed. (B) Complex formation with activated Smad2. Proteins from shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an antibody against Smad2/3 (or IgG as control) and immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies recognizing Smad2/3, P-Smad2, Smad4, and TIF1-γ. Inputs are shown. These results are representative of 3 experiments with different samples.

TGF-β signalization pathway is amplified and complex formation is modified in the absence of Gfi-1B. (A) Increase of Smad2 phosphorylation in the absence of Gfi-1B. shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells were stimulated or not with TGFβ1 (R&D Systems) for 1 hour. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies indicated on the left of the figure (as controls, Smad2/3 and β-actin). Three experiments with different samples were performed. (B) Complex formation with activated Smad2. Proteins from shControl- or shGfi-1B–transduced K562 cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an antibody against Smad2/3 (or IgG as control) and immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies recognizing Smad2/3, P-Smad2, Smad4, and TIF1-γ. Inputs are shown. These results are representative of 3 experiments with different samples.

So far, we have shown that Gfi-1B knockdown led to both altered TGF-β signaling and impaired erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. We thus hypothesized that Gfi-1B–mediated regulation of TGF-β signaling might contribute to its function in erythroid development. Indeed, TGF-β signaling was described as triggering erythroid differentiation from immature progenitors through the formation of a protein complex between phosphorylated Smad2/3 and TIF1-γ. To address this question, we investigated whether the formation of the complex between phosphorylated Smad2/3 and TIF1-γ was modified in K562 cells depleted for Gfi-1B by performing coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Strikingly, we found that, whereas phosphorylated Smad2 associated to both Smad4 and TIF1-γ in shControl cells, complexes between phosphorylated Smad2 and TIF1-γ did not form in Gfi-1B knockdown cells (Figure 7B). Thus, depletion of Gfi-1B specifically prevents the formation of the Smad2/TIF1-γ complex, which is known to be required for erythroid differentiation27 but does not affect the association between Smad2 and Smad4, which is responsible for the inhibition of cell proliferation. Consistent with this result, the proliferation of immature CD34+ progenitors was indeed inhibited in the absence of Gfi-1B (Figure 1B).

Altogether, our data suggest that Gfi-1B controls erythroid and megakaryocytic development at the bipotent MEP stage, at least in part, by regulating TGF-β signaling.

Discussion

We here show that Gfi-1B, a zinc-finger transcription factor, is essential at early stages of human adult hematopoietic differentiation and more specifically at the bipotent MEP stage. Gfi-1B is highly expressed in the MEP cell population; and, in its absence, a reduction in proliferation and an inhibition of differentiation of immature progenitors are concomitantly observed.

Interestingly, whereas erythroid progenitors from fetal liver of GFI-1B−/− mice form large dispersed colonies of immature progenitors,7 shGfi-1B MEPs do not proliferate or differentiate in semisolid medium in response to a cocktail of growth factors. These results suggest that Gfi-1B target genes may be different in mouse embryonic and human adult stem cells. The existence of potential differences between human and mouse Gfi-1B functions is further supported by the fact that Gfi-1 expression, which is maintained in Gfi-1B–depleted CD34 cells, fails to restore the Gfi-1B deficiency. This result is indeed in sharp contrast with data showing that GFI1/GFI1B knock-in mice display normal hematopoiesis.33 However, the development of the inner ear hair cell is altered in these mice, suggesting that Gfi-1 and Gfi-1B may have some different functions. In particular, one Gfi-1 function that is not shared by Gfi-1B is to enhance STAT3-mediated transactivation by binding and sequestrating the STAT3 inhibitor PIAS3.34 Furthermore, we15 and others16 have shown that LSD1/CoREST mediated the repression induced by Gfi-1 and Gfi-1B. We found that, contrary to Gfi-1B, Gfi-1 did not recruit LSD1/CoREST to the TGFBR3 promoter (data not shown). Thus, it seems probable that Gfi-1 cannot replace Gfi-1B in its specific function in human immature hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Comparative transcriptomic analyses of Gfi-1B knocked down CD34+ or MEP show that, among the 60 genes that are up-regulated in both CD34+ cells and MEP depleted for Gfi-1B, several genes encode proteins involved in TGF-β signaling. In particular, the expression of one of its receptors, the coreceptor TβRIII, was strongly increased both in CD34+ cells and in MEPs depleted for Gfi-1B, suggesting that Gfi-1B modulates TGFBR3 gene expression in immature MEPs. In accordance with the up-regulation of TGFBR3 transcription in the absence of Gfi-1B, we found that Gfi-1B binds to the proximal part of the TGFBR3 promoter and represses its activity. This result, together with the rescue of the erythroid and megakaryocytic maturation observed after the TβRIII knockdown in Gfi-1B–depleted CD34+ cells, indicates that TβRIII repression is responsible for Gfi-1B–mediated regulation of erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis.

TGF-β superfamily members have indeed been described as regulating erythropoiesis mainly through Smad pathways.35,36 Here we show that Smad signaling pathway is altered in the absence of Gfi-1B in erythroid cells. Indeed, the knockdown of Gfi-1B increases Smad2 phosphorylation. Surprisingly, TGF-β stimulation does not increase the phosphorylation of Smad2 in K562 cells. However, many signaling pathways are constitutively activated in K562 cells because of the presence of Bcr-Abl; this result suggests that TGF-β signaling pathway is also activated in K562 cells. The increase in Smad2 phosphorylation that follows the increase of TβRIII expression in the absence of Gfi-1B may be the result of the enhanced activation of TβRI, which is responsible for Smad2 phosphorylation. A striking observation we made is that, whereas both Smad2/Smad4 and Smad2/TIF1-γ complexes form in the presence of Gfi-1B, formation of Smad2/TIF1-γ is completely impaired in Gfi-1B–depleted erythroid cells. This result provides a simple explanation for our data showing that Gfi-1B knocked down cells exhibit (1) an inhibition in progenitor proliferation, which is known to result from Smad2/Smad4 association and (2) an impairment in erythroid development, which was described as requiring Smad2/TIF1-γ association.27 In the same line, knockdown of TF1γ in immature hematopoietic leads to altered erythroid differentiation,27 and mutations in the moonshine gene that encodes the zebrafish ortholog of mammalian TIF1-γ were shown to specifically disrupt both embryonic and adult hematopoiesis, resulting in severe red blood cell aplasia.37

Why is the formation of Smad2/TIF1-γ complexes compromised in cells lacking Gfi-1B? It is tempting to speculate that increased TβRIII expression in the absence of Gfi-1B is in part responsible for the lack of Smad2/TIF1-γ association. Enhanced Smad2 phosphorylation resulting from TβRIII overexpression may specifically impair its interaction with TIF1-γ, whereas its association to Smad4 would remain unaffected. Alternatively, TβRIII overexpression might modify an additional component of the pathway that would regulate Smad2/TIFγ interaction. Gfi-1B, through regulation of TβRIII expression, may also modify TGF-β signaling through alternative non-Smad pathways. Indeed, TβRIII has been demonstrated to regulate the MAPK p38,23 the small GTPase Cdc42,22 and the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathways24 through its interaction with β-arrestin 2.22 Accordingly, among the genes up-regulated in cells deficient for Gfi-1B, we found Egr-138 and Rho-B,39 also known to participate to this non-Smad TGF-β signaling. In addition, TβRIII also binds inhibin40 and bone morphogenetic protein41 to regulate both activin and bone morphogenetic protein-mediated signaling.41-43 In any case, the current data suggest that the expression balance between TGF-β receptors might be a key parameter in controlling cellular responses to TGF-β signaling during hematopoiesis. The nature of the factors that regulate TβRIII expression in addition to Gfi-1B and the TβRIII function responsible for the role defined here is currently under investigation.

In conclusion, we here propose that Gfi-1B represses TβRIII in MEPs and thereby controls the ability of these cells to differentiate in response to TGF-β. This study provides the first evidence for a crosstalk between a transcriptional repressor and a cytokine signaling pathway during erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr J. Massagué (New York, NY) for the TIF1-γ antibody, Dr E. Soler (Rotterdam, The Netherlands) for Gfi-1B shRNA, Dr A.M. Lennon-Duménil (Paris, France) for critical reading of the manuscript, Dr L. Bénit (Paris, France) for analyzing DNA sequences, Dr E. Lauret (Paris, France) for helpful discussion, F. Letourneur and N. Cagnard (Paris, France) from “Séquençage et Génomique” and informatics platforms for hybridization on Affymetrix microarrays and analysis of the results, and B. Chanaud, L. Stouvenel, and M. De Sousa (Paris, France) from Flow Cytometry platform of Cochin Institute.

This work was supported by Inserm, France and Fondation de France (grant 20007002071). B.L. was supported by a fellowship from Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer.

Authorship

Contribution: V.R.-H. and B.L. conceived, designed, and performed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, and contributed to writing the manuscript; V.B. analyzed and interpreted cytology and approved the final manuscript; G.C.B. provided plasmid constructs and approved the final manuscript; F.H. performed FACS analysis and cell sorting purification, provided critical ideas, and approved the final manuscript; and D.D. conceived and performed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, coordinated the research, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dominique Duménil, Institut Cochin, Batiment G. Roussy, 27 rue du Faubourg Saint-Jacques, 75014 Paris, France; e-mail: dominique.dumenil@inserm.fr.

References

Author notes

V.R.-H. and B.L. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Gfi-1B knockdown impairs proliferation in primary human immature progenitor cells. (A) Experimental protocol to test the effects of Gfi-1B knockdown in immature primary human progenitors. CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood and amplified for 24 hours in the presence of IL-3, SCF, TPO, and FL and then infected with lentiviruses carrying shControl or shGfi-1B. Forty-eight hours after infection (D4), CD34+GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured in liquid culture in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and EPO to induce the erythroid (E0-E7) or SCF and TPO for megakaryocytic differentiation (T0-T10). (B) Proliferation of shControl or shGfi-1B CD34+ cells. After CD34+GFP+ sorting, cells were cultured in the presence of SCF, FL, IL-3, and TPO and counted every day (corresponding to D5-D9 in the experimental protocol described in panel A) in the presence of Trypan blue. Error bars represent SD; n = 4 from different samples. (C-D) Flow cytometry histograms after annexin V and 7-AAD staining (C) and proportion of the cells in different phase of the cell cycle after 7-AAD and propidium iodide staining (D). Infected shControl and shGfi-1B CD34+ cells were analyzed at D5 and D7 or D9. (E) ShGfi-1B efficiency during erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. Cell lysates (noninfected cells [NI] and shControl or shGfi-1B for infected cells) were prepared at different times after induction of erythroid (E3 and E6) or megakaryocytic differentiation (T3 and T4) and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against Gfi-1B, Gfi-1, p21cip/waf1, or β-actin (as control). The membrane was highly exposed after hybridization with Gfi-1B antibody to determine the efficiency of the Gfi-1B shRNA.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/115/14/10.1182_blood-2009-09-241752/4/m_zh89991050710001.jpeg?Expires=1769134539&Signature=lEmi48zkPKL7jA-4Dm3Js-mHdFKdu9kgUWgwE7CnxRoHMTmVPRaCA5Zi-5~p2LZRurrrMQ0oawAfF4duurqogyNoILUcOF7JdFqSOHAUM8-gvmyvZcc5Gxfw3bR~gK6vX3PVo5WsNxa9AxtWDh~B2Rxn~iR-9sNVIIZlLd4CTpkwJeLSPJE5WQa0BkoWL9zS9y~pWbZLGh1jctUgxpKeA0P6fKcYtRsbWdyJNKQyEkhbNKpvnAta8n9opIC0KaaOe~~n3Cufr5zpxd9-7BYL6Eaw6V-sU-fJPmTIhlDKGluWg3ocbykMqoUYjjaRGikIMOptmDK2as7G6bJRBM5EBg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)