Genetic disorders of iron metabolism and chronic inflammation often evoke local iron accumulation. In Friedreich ataxia, decreased iron-sulphur cluster and heme formation leads to mitochondrial iron accumulation and ensuing oxidative damage that primarily affects sensory neurons, the myocardium, and endocrine glands. We assessed the possibility of reducing brain iron accumulation in Friedreich ataxia patients with a membrane-permeant chelator capable of shuttling chelated iron from cells to transferrin, using regimens suitable for patients with no systemic iron overload. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of Friedreich ataxia patients compared with age-matched controls revealed smaller and irregularly shaped dentate nuclei with significantly (P < .027) higher H-relaxation rates R2*, indicating regional iron accumulation. A 6-month treatment with 20 to 30 mg/kg/d deferiprone of 9 adolescent patients with no overt cardiomyopathy reduced R2* from 18.3 s−1 (± 1.6 s−1) to 15.7 s−1 (± 0.7 s−1; P < .002), specifically in dentate nuclei and proportionally to the initial R2* (r = 0.90). Chelator treatment caused no apparent hematologic or neurologic side effects while reducing neuropathy and ataxic gait in the youngest patients. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical demonstration of chelation removing labile iron accumulated in a specific brain area implicated in a neurodegenerative disease. The use of moderate chelation for relocating iron from areas of deposition to areas of deprivation has clinical implications for various neurodegenerative and hematologic disorders.

Introduction

Tissue iron overload and ensuing organ damage have generally been identified with transfusional hemosiderosis and genetic hemochromatosis.1 Liver, heart, and endocrine glands are among the most affected organs in these forms of systemic iron overload.1 The source of tissue iron overload has been traced to plasma iron originating from enteric hyperabsorption of the metal and/or enhanced red cell destruction. The labile forms of plasma iron (LPI) that appear as transferrin become saturated, permeate into particular cell types by unregulated mechanisms, and cause labile iron pools to raise and challenge cellular antioxidant capacities.2

However, in chronic inflammation3 and in various genetic disorders,4 iron accumulates in particular cell types attaining toxic levels, even in the absence of circulating LPI and often even in iron-deficient plasma. In Friedreich ataxia (FA), an expansion of a GAA repeat in the first intron of the nuclear encoded frataxin gene5,6 results in underexpression of a mitochondrial protein involved in the assembly of iron-sulphur cluster proteins (ISPs) and/or in protecting mitochondria from iron-mediated oxidative damage.7 The defective ISP formation that causes a combined aconitase and respiratory chain deficiency (complex I-III) leads in turn to mitochondrial accumulation of labile iron8,9 and ensuing oxidative damage in brain, heart, and endocrine glands. However, the pathophysiologic role of mitochondrial iron accumulation in oxidative damage found in FA5,9 and other neurologic disorders10,,–13 has not been resolved.

In analogy to transfusional iron overload, histopathologic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of FA patients have shown that iron accumulates not only in the heart but also in the spinocerebellar tracts (dentate nuclei) and spinal cord.10 Those and other pieces of evidence implicated labile iron in the oxidative damage and called for the use of antioxidants and/or chelators of iron as possible treatments of FA and other neurologic disorders.13,,,,–18 Initial studies with the antioxidant idebenone in FA indicated some cardioprotective effect but no improvement in ataxia.17 On the other hand, iron chelation therapy has not been used in FA for 2 main reasons: (a) lack of validated clinical methods for assessing the levels of accumulated iron in the brain and the accessibility of iron to chelators; and (b) the risk of a chelating drug being neurotoxic and/or inducing global iron depletion in hematologically normal or mildly hypoferremic patients.19,20 However, the recent adaptation of MRI for assessing iron accumulation in the livers21 and hearts of siderotic patients22,23 and in the brain10,15,24 has offered a new possibility for in situ assessment of chelation treatment in FA and other forms of neurodegeneration11,12 with brain iron accumulation (NBIA).13

In the search for candidate chelators with clinical record, we focused on membrane-permeant agents that demonstrably reduced the production of reactive oxygen species (ROSs) in living cells by reducing the levels of intracellular labile iron.25 In specifically selecting the orally active deferiprone (3-hydroxy-1,2-dimethylpyridin-4-one; DFP) in preference to other agents, we considered 5 essential properties for treating a condition of local rather than global iron accumulation26 : (a) permeation, which endows the drug with the ability to cross membranes, gain access to cell organelles, and reduce iron-dependent free-radical formation2 ; (b) extrahepatic iron chelation ability, as applied to cardiac siderosis22,27 ; (c) the ability to act selectively on the most accessible iron pools defined as labile iron pools,28,29 as well as on subcellular compartments,2 without depleting transferrin-bound iron from plasma30 ; (d) the ability to transfer iron chelated from the labile pools of cells to biologic acceptors such as circulating transferrin30 ; and (e) the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier.31

An efficacy-toxicity phase 1-2 open trial with DFP was performed on adolescent FA patients who have been on idebenone for several years and who had a normal echocardiogram but showed no improvement in brain MRI profiles or neurologic indices. A treatment based on moderate chelation regimens based on oral DFP was applied with the view of reducing iron accumulated in specific brains areas, such as the dentate nuclei, and eventually ameliorating the neurologic condition without adversely affecting hematologic parameters.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and study design

Patients (age 14-23 y) were diagnosed with FA by detecting the trinucleotide repeat expansion in the first intron of the frataxin gene. They were randomly selected from a population that had been treated with idebenone (10 mg/kg/d, in 3 oral doses) for at least 2 years prior to inclusion and continued antioxidant treatment during this study. The protocol used was designed to initiate treatment with a relatively low daily dose of DFP and with application of strict criteria for suspending treatment following lack of tolerance due to neuronal, muscular, or gastrointestinal discomfort or hematologic changes. A group of 13 patients (4 males and 9 females) were randomly subselected to receive either 20 or 30 mg/kg/d DFP (procured from Apopharm, Toronto, ON, Canada) divided into 2 daily oral doses for up to 6 months. A plan of staggered patient enrollment was applied with the view of minimizing the risk of drug toxicity. Groups of 3 patients entered the study every 2 months, at 2 week intervals. Treatment was initiated with the lower dose. If tolerance to treatment with evidence of efficacy was found in 2 of 3 patients, a second group of patients enrolled with the same dose. If tolerance was found without evidence of efficacy in 2 of 3 patients, the second group of 3 patients enrolled with the higher dose. If intolerance developed in 1 of 3 patients, the treatment was continued with only the 2 other patients in the group. Only 9 patients completed a 6-month course of DFP, with brain MRI examinations performed at inclusion and at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months of treatment. As control for no DFP treatment, we used 9 patients who were only on idebenone therapy. The protocol was promoted by Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, approved by the institutional ethical committee, and registered at the National Health Authority (AFSSAPS) and at the International Protocol Registration System (www.clinicaltrials.gov; study ID: NCT00224640). In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, a written informed consent was obtained from patients and parents.

The International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Score (ICARS) was used to assess the symptoms of ataxia before and after months 1 and 6 of the study32 with 4 subscales: posture and gait disturbance, kinetic functions, speech disorders, and oculomotor disorders. Scores were summed to give a total score (0-100), with higher numbers indicating worse ataxia. The Perdue Pegboard test applied by the same investigator on a limited number of patients was used for assessing the speed performance, delicate movements, and manipulative dexterity. The participant was asked to insert as many nails as possible into preset holes, linearly drilled into a wooden board, in a limited space of time (20 minutes with 2 hands, separately and together).

The risk of agranulocytosis and other potential adverse effects of DFP observed in 1% of thalassemia patients19,26 led us to closely monitor patients for neutropenia, agranulocytosis, musculoskeletal pain, and zinc deficiency, which included weekly blood counts; serum iron, ferritin, and transferrin concentrations; and renal and liver functions.

MRI measurements

Clusters of iron cause local nonhomogeneity in the magnetic field and therefore decrease the MRI signal of surrounding water. This leads to variations in the apparent transverse relaxation rate (R2*) or its inverse, T2*, the indexes used to quantify MRI signal decay.11,20 Assuming a homogeneous external magnetic field, changes in R2* reflect variations in local iron concentration or in deoxyhemoglobin levels due to regional changes in blood perfusion.31 MRI examinations were done on a 1.5 T Signa unit (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) using a phased array head coil. Deep gray structures were localized by using a T2*-weighted echo-planar sequence. A voxel encompassing the left and right nuclei (dimensions 6 × 3 × 2 cm3) was positioned on the largest section of dentate nuclei, and its automatic shimming was performed to minimize regional magnetic field variations. For each selected section, iron monitoring was performed using a single-slice multigradient echo sequence (field of view 24 cm, 255 × 224 matrix; slice thickness: 5 mm; TR (time of repetition): 400 ms, 10 echoes at TE (time of echo) from 10 ms to 100 ms; flip angle: 50°; acquisition time: 3 minutes). Volume selection for shimming and single-slice multigradient echo acquisition was repeated at the level of pallidal nuclei. The determination of R2* was performed from data of the multigradient echo sequences by adjusting the Si signals, in each pixel, obtained at echo times TEi (i = 1.10) according to the equation Si = So.exp (−R2* × TEi). A high-resolution image of local R2* values was built and the mean value of R2* was calculated in various regions of interest (ROIs) by the same radiologist. At 1.5 T, the image resolution attained was adequate for obtaining only a single elliptical ROI of 10 mm2, typically placed at the center of each nucleus to minimize R2* variance. MRI measurements were made twice on the same day at 2-hour intervals. As internal control, several (2 or more, depending on the size of the region) circular ROIs of 24 mm2 were drawn in the white matter of cerebellar hemispheres posterior to the dentate nuclei, where iron concentration is assumed to be low, and in pallidal and thalamic nuclei.

Statistical analyses

At the basal state, R2* values in the various structures were compared using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model, taking into account the individual levels with both the cerebral structure and the side as categoric covariates. For each cerebral structure, repeated MRI measurements over time were analyzed using a GEE model with the time of measurement as factor. Individual contributions were weighted using the inverse of the variance of R2* in the corresponding region of interest. All calculations were carried out using the GEE procedure from the geepack library, R statistical package (http://www.R-project.org). A P value less than .05 was considered significant. Tests were adjusted for multiple comparisons according to the Bonferroni rule. One-way analysis of variance (Anova) and Student paired t tests were carried out with Origin v 7.5 (Originlab, Northampton, MA).

Results

Changes in morphology and in iron levels in specific brain areas

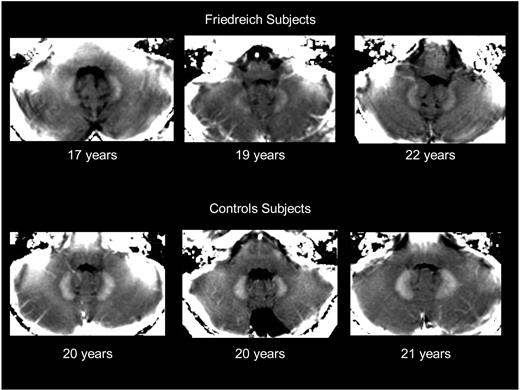

The images displayed in Figure 1 were selected among those obtained from FA patients at the onset of chelation treatment (n = 9 who completed the treatment) and among age-matched adolescents who were admitted for unrelated conditions. The images highlight the morphologic changes in size and shape that dentate nuclei undergo in 3 representative adolescent FA patients compared with age-matched controls (Figure 1).

MRI visualization of iron accumulation in dentate nuclei of 3 young patients with Friedreich ataxia and 3 healthy age-matched subjects. The figure shows a parametric image of R2* values in posterior fossa, derived from the multigradient echo sequence done at 1.5 T. Dentate nuclei with high R2* values appear whiter than surrounding cerebellum, smaller, and irregularly shaped in FA patients compared with control subjects. R2* values of the adjacent cerebellum have values in the order of 14 s−1, confirming good regional homogeneity of the magnetic field. The R2* values are given in the text. The above images are displayed following equal windowing and leveling of the R2* maps.

MRI visualization of iron accumulation in dentate nuclei of 3 young patients with Friedreich ataxia and 3 healthy age-matched subjects. The figure shows a parametric image of R2* values in posterior fossa, derived from the multigradient echo sequence done at 1.5 T. Dentate nuclei with high R2* values appear whiter than surrounding cerebellum, smaller, and irregularly shaped in FA patients compared with control subjects. R2* values of the adjacent cerebellum have values in the order of 14 s−1, confirming good regional homogeneity of the magnetic field. The R2* values are given in the text. The above images are displayed following equal windowing and leveling of the R2* maps.

The mean R2* constants (in s−1) calculated for various ROIs of a brain area of a given individual showed reproducibility (measured by the variation coefficient in repeated examinations) of 4% in dentate nuclei and 6% in the cerebellar cortex. The calculated R2* values in the dentate nuclei were significantly but not substantially higher in FA than in controls (R2* = 18.3 ± 1.7 s−1 compared with 16.6 ± 1.2 s−1; P < .05; n = 9 in each group). In addition, the R2* values in FA (n = 9) were relatively higher in pallidum (19.6 ± 1.9 s−1; P < .05) than in their dentate nuclei and lower in their cerebellum and thalamus (13.9 ± 0.6 s−1, P < .05 and 15.2 ± 2.8 s−1, P < .05, respectively), in accordance with the relative amount of iron chemically detected in those areas in healthy individuals.15,33,–35

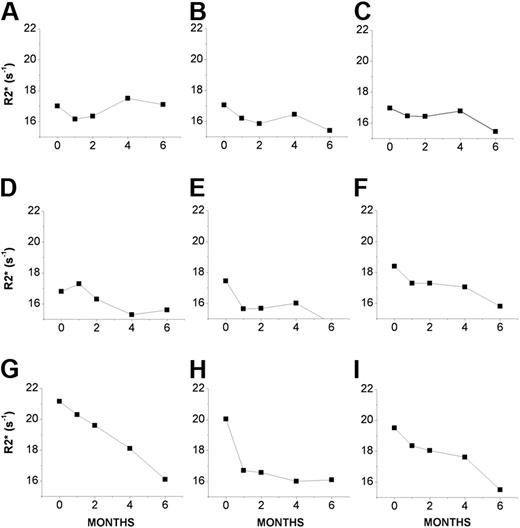

Unlike in a previous study,10 the increased R2* values observed in dentate nuclei of FA patients showed no correlation with age, possibly because of the small group of patients who participated in the study. The increased R2* values might reflect changes in (a) accumulation of iron as proposed earlier10,15,24,33,–35 and by analogy to what has been obtained in other organs in systemic iron overload21,–23 and (b) deoxyhemoglobin levels underlying reduced blood perfusion caused in damaged brain areas.36 Although the chemical nature of the accumulated iron is not known, an iron chelator that might have access to the affected areas could be instrumental in discerning between the relative contribution of the above 2 factors and provide some insights into the nature of the local iron contributing to the R2* values. After 20 to 30 mg/kg/d DFP administration to 9 FA patients, there was a significant decrease in the relaxation rate R2* in dentate nuclei from 18.3 s−1 (± 1.7 s−1) at treatment onset to 16.2 s−1(± 0.8 s−1; P < .001) after 1 month, to 16.6 s−1 (± 1.3 s−1; P < .002) after 2 months, to 16.4 s−1 (± 0.8 s−1; P < .01) after 4 months, and to 15.7 s−1 (± 0.7 s−1; P < .002) after 6 months of DFP administration (Figure 2). Although the profiles of R2* values differed among patients in the course of DFP treatment, they reached a basal level after 2 to 4 months. Moreover, no short-term difference was observed between the 2 doses of DFP (20 and 30 mg/kg/d), suggesting that maximal efficacy might apparently have been reached with the lower dose. However, after a 6-month course of treatment with DFP on 9 patients, there were no morphologic changes in dentate nuclei detected or any significant changes in R2* values in other sections of the brain. The respective mean plus or minus standard deviation (SD) of R2* values at months 0 and 6 were 19.6 s−1 (± 1.9 s−1) vs 19.2 s−1 (± 1.4 s−1) in pallidal nuclei, 15.2 s−1 (± 1.9 s−1) vs 14.6 s−1 (± 0.9 s−1) in thalami, and 13.9 s−1 (± 0.4 s−1) vs 13.9 s−1 (± 0.53 s−1) in cerebellar white matter regions. A comparable group of patients treated only with idebenone for 6 to 12 months showed no significant change in R2* in any of the above regions of the brain, including the dentate nuclei (N.B. and A.M., June 2006, unpublished).

R2* values of dentate nuclei of 9 individual FA patients undergoing treatment with deferiprone (20-30 mg/kg/d) for up to 6 months. Mean R2* constants (in s−1) of dentate nuclei of individual FA patients (A-I) were obtained at the indicated month of treatment (1- to 2-month intervals) as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.”

R2* values of dentate nuclei of 9 individual FA patients undergoing treatment with deferiprone (20-30 mg/kg/d) for up to 6 months. Mean R2* constants (in s−1) of dentate nuclei of individual FA patients (A-I) were obtained at the indicated month of treatment (1- to 2-month intervals) as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.”

Analysis of R2* changes after 6 months of DFP treatment (Figure 2) revealed that the higher the R2* was at the onset of treatment, the greater the decrease was in R2* (Figure 3). The relative change in R2* correlated linearly with the initial R2* value (Figure 3 inset). Only 1 of 9 treated patients (with initially low R2* value) showed no significant change after 6 months of DFP treatment. We interpret these results as indicating that DFP chelates labile iron that specifically accumulated in dentate nuclei.

Absolute and relative changes in R2* of individual FA patients after a 6-month treatment with DFP. The boxes represent the change in R2* constants (s−1) attained between 0 and 6 months of treatment with DFP (values taken from Figure 2), with the thick line representing the value at the end of treatment. The dotted lines represent the respective mean R2* values of 18.3 ± 1.6 s−1 and 15.7 ± 0.7 s−1 obtained at 0 and 6 months, respectively. The mean R2* values and the individual R2* values for each patient at 0 and 6 months were significantly different (P < .002; Anova test). The inset depicts the percentage decrease in R2* (calculated as [R2* {month 0} − R2* {month 6}]/[R2* {month 0}] ×100) versus the initial R2* (month-0 treatment) that yielded by linear regression analysis a slope of 4.2 ± 0.90 (r = 0.87, n = 9, P < .003).

Absolute and relative changes in R2* of individual FA patients after a 6-month treatment with DFP. The boxes represent the change in R2* constants (s−1) attained between 0 and 6 months of treatment with DFP (values taken from Figure 2), with the thick line representing the value at the end of treatment. The dotted lines represent the respective mean R2* values of 18.3 ± 1.6 s−1 and 15.7 ± 0.7 s−1 obtained at 0 and 6 months, respectively. The mean R2* values and the individual R2* values for each patient at 0 and 6 months were significantly different (P < .002; Anova test). The inset depicts the percentage decrease in R2* (calculated as [R2* {month 0} − R2* {month 6}]/[R2* {month 0}] ×100) versus the initial R2* (month-0 treatment) that yielded by linear regression analysis a slope of 4.2 ± 0.90 (r = 0.87, n = 9, P < .003).

Changes in clinical parameters during treatment

An initial treatment was applied on 2 FA patients using a DFP dose of 80 mg/kg/d (2 daily doses), which is in the therapeutic range used on thalassemia subjects15,16,21 and recommended by Apopharm. The treatment was suspended after 2 weeks due to serious adverse reactions in 1 of the patients who included fatigue, headache, nausea, dizziness, poor head control, abnormal eye movements, and fluctuating consciousness. An inquiry revealed that the affected patient had been on a cloroquine-proguanyl prophylactic therapy for malaria for 2 weeks, raising the possibility of drug-drug interactions. However, because such events have not been reported in thalassemic patients receiving DFP for transfusional iron overload,19,20,26 we assume that FA patients, having no systemic iron overload, might display a lower toxicity threshold for DFP. Another possibility is that an excessively high peak level of drug is attained in plasma after oral intake of unitary doses of 40 mg/kg/d twice a day rather than 25 mg/kg/d doses taken thrice a day by thalassemia patients.19

The 6-month study plan was therefore redesigned and dosing limited to 20 to 30 mg/kg/d DFP. Of the 13 patients who entered the new protocol, 3 were withdrawn because of complaints of muscular-skeletal pain, dizziness, or Guillain-Barré syndrome and 1 because of agranulocytosis that resolved afterward. Of the 9 patients who completed the study, a neurologic improvement was noted by parents and uninformed relatives within 4 weeks of treatment. Constipation, incontinence, and some subjective signs of peripheral neuropathy disappeared within 2 months. Limb extremities, which were cold, mottled, and hypersensitive, warmed in several patients, with the sensation of feeling one's feet and the floor surface again. Delicate movements and manipulative dexterity (eg, handwriting, keyboard typing, hairdressing, eye make-up application) and speech fluency were reportedly improved in several patients (Table 1). General strength, quality of sitting, standing, and facility of transfers (from bed to wheelchair or toilets) also improved. The youngest (14 years) treated patients benefited most from the trial in terms of delicate movements, balance, stability, and autonomy. These observations were seemingly unbiased, as they were independently and consistently reported by the parents and/or by supporting personnel (Table 1). They yielded modest but significant changes in ICARS scores after 6-month treatment, with the youngest patients attaining at least 10% improvement. The inclusion of patients at a higher dose of DFP (30 mg/kg/d) essentially reproduced the above observations in terms of tolerance and relative efficacy of DFP, improvement in speed of performances, and dexterity (Table 1). The Perdue Pegboard test, which objectively assesses the impact of the drug on manipulative dexterity, was applied on 3 patients randomly selected at the onset of treatment with DFP. The mean scores fell significantly (P < .05) from 44 (± 7) to 35 (± 5) after a 6-month chelation treatment (not shown).

Changes in biochemical and hematologic parameters during treatment

Administration of DFP resulted in a small but significant decrease in serum ferritin levels in only 2 patients but with no significant change in hemoglobin or plasma iron levels (patients C and I, Table 2). A retroactive inquiry revealed that the 2 patients entered the study after recovering from recent infectious episodes, possibly causing an elevated serum level of the acute-phase reactant ferritin.

Discussion

Iron accumulation has generally been taken as an indication for potential biologic damage due to the propensity of the metal to evoke oxidative stress when present in labile forms.37 This has been assumed to be the case in organ iron overload resulting from the presence of high levels of LPI2 and in various disorders in which iron accumulates in particular organs as a result of chronic inflammation3 or disorders of cell iron metabolism.4,38 For systemic iron overload, the use of iron chelators has had an unquestionable therapeutic record, particularly in the treatment of hemosiderosis of various types14,20,25 and more recently in preventing or reversing iron-evoked cardiac failure in thalassemia.23,27,39 A major contribution to the recent success in the treatment of iron overload is the advent of noninvasive techniques for assessing organ iron overload that paved the road for optimizing the chelation regimens, particularly MRI measurements of iron accumulation in organs such as the liver and heart.21,–23

In FA, the evidence of iron accumulation in mitochondria5,8,9 was supported by studies indicating early iron accumulation in the cerebellum of patients (particularly the dentate nuclei).10,15 However, the pathologic role of iron as a causative or exacerbating factor in FA5,40 and in other neurologic disorders11,–13,16 has remained a matter of debate. Similarly controversial is the use of iron chelators for treating FA and other neurologic conditions.14,18,41 In these diseases the proposed target of chelators is detoxification of iron accumulated in specific brain areas and for FA possibly also in the heart and endocrine glands. However, in FA, where there are either normal or marginally lowered levels of plasma iron,42,43 it may be considered inadvisable to chelate iron needed to support iron-sulphur cluster formation,44,45 which is already impaired due to frataxin deficiency.5 The design of a chelator that is orally active, membrane permeant, and capable of scavenging iron from mitochondria of specific areas of the brain, while sparing the bulk of physiologically essential iron, is a challenging task.

The present study was an initial attempt to approach that problem at the clinical level, with the view of assessing by MRI the accessibility of iron accumulated in dentate nuclei of FA patients to a chelator in clinical use in iron overload at doses considered to be safe.19 The FA patients engaged in the phase 1-2 open-label study by random selection were in the 14- to 23-year-old age range, all treated for several years with the free-radical scavenger and antioxidant idebenone.17,46,47 These patients showed essentially no functional cardiac complication or abnormal echocardiograms and yet there were no indications for R2* changes in any area of the brain or neurologic effects attributable to antioxidant treatment. At the onset of the study, the dentate nuclei of the 9 randomly selected adolescent FA patients showed MRI-detectable alterations in shape and R2* values that were marginally but significantly different from healthy individuals (Figure 1). This reinforces the previous neuropathologic observations of iron accumulation and tissue damage10,15 but not unequivocally, because changes in R2* in damaged brain areas could also be attributed to changes in deoxyhemoglobin concentrations due to altered blood perfusion.36 However, if the R2* value represents even in part an accumulation of iron in specific areas of the brain (eg, the spinocerebellar and pyramidal tracts, spinal cord, and dorsal root ganglia), it would mean that iron accumulation might be a relatively early event in FA, since it was evident in very young patients. We reasoned that if in FA some component of R2* might be in equilibrium with labile iron forms, namely those that are redox active and potentially chelatable,25 then chelation treatment might decrease R2* values in the areas of interest and possibly confer antioxidant protection. The alternate explanation that an iron chelator might affect blood perfusion is not inconceivable but is highly unlikely.

The selection of the hydroxypyridinone deferiprone, an iron chelator that has been approved in Europe for treating some cases of thalassemia,19,20,26,38 was based on several criteria: (a) the orally active membrane-permeant iron chelator29 efficiently removes iron from mitochondria in living cells2,48 ; and (b) the chelated iron complex, deferiprone-Fe, can transfer iron to transferrin30 (this condition is satisfied as long as transferrin is not iron saturated, as is the case with FA patients [Table 1 and Wilson et al42 ], and the chelator is used at moderate doses); and (c) because of its small molecular weight and favorable chemical properties, the drug was also expected to readily cross the blood-brain barrier, as animal studies indicated.31 The selected dosage of deferiprone was 20 to 30 mg/kg/d, namely one fourth the daily dose used in thalassemia major19,20 and in the range to have experimentally no adverse effects on iron-dependent brain enzymes.31

The initial purpose of this efficacy-toxicity study was to monitor chelator-evoked changes in brain iron deposits using MRI, with the view of assessing the feasibility of conducting a long-term evaluation of DFP on disease progression. The selection of R2* measurements as indicators of brain iron deposits was based on the wide experience gained with MRI,15,33,–35 particularly in animal and clinical studies in which DFP demonstrably reversed the changes in heart T2* values caused by iron overload and improved cardiac ejection fraction.22,23 In FA, deferiprone given at relatively low daily doses, efficiently and progressively decreased iron accumulated in dentate nuclei in 8 of 9 patients, as reflected in the R2* values (Figure 2). For most treated patients, the major reduction in R2* was within 2 months of treatment, and the larger the initial R2* value, the more robust and proportional the change evoked by the chelator (Figure 3 and inset). This would indicate that the R2* values provide a quantitative measure for chemical forms of potentially chelatable iron accumulated in the dentate nuclei. Moreover, with our knowledge of deferiprone's ability to scavenge cell iron,2,29,48 and assuming the concentration of chelator attained in the brain to be similar to that in plasma (at most 20-30 μM at peak values after a single 10 mg/kg/d dose of chelator and a t½ value of 2-3 hours in plasma),26 one can deduce that the R2* in the dentate nuclei represents (a) accumulated forms of iron that are labile and directly chelatable and/or (b) accumulated forms of iron (eg, ferritin) that chelation can indirectly reduce by triggering proteolytic degradation of ferritin. Thus by binding labile iron, deferiprone might shift the equilibrium away from cell-accumulated metal, as shown before by us in myeloid cells49 and implied in recently published studies on biochemical properties of ferritin iron.50,51 As to the chemical nature of the labile iron forms, those might be composed of low–molecular weight iron complexes2 and/or of iron loosely bound to enzymes such as hydroxylases.31 This is in line with the observed susceptibility of frataxin-deficient systems to iron-driven ROS formation and oxidative damage and their protection by iron chelators41 but apparently not with the lack of changes in mitochondrial labile iron detected in lymphoblasts derived from FA patients.52

An interesting observation was that, other than dentate nuclei, no other brain areas of FA patients underwent any significant change in R2* upon chelation treatment. This apparent selectivity can be explained by 1 or more of the following possibilities: (a) the chelator has no access to areas other than the dentate nuclei; (b) the forms of iron in other areas are not easily chelatable, either because they are compartmentalized or associated with degradation products of ferritin such as hemosiderin45 ; or (c) other factors contribute to R2* in areas outside the dentate nuclei. To our knowledge, the present study provides the first in situ demonstration of iron chelation acting in a specific area of the brain in the clinical setting.

In the present efficacy/toxicity phase 1-2 study, there were no a priori expectations regarding clinical benefits that could be obtained in a 6-month trial period. However, particular consideration had to be given to the appearance of any adverse reactions to treatment and especially to hematologic changes that even a mild chelation treatment could evoke in FA patients who were already borderline hypoferremic-hypoferritinemic at inclusion (Table 2). As shown, the fact that 1 of 13 patients withdrew from the study because of agranulocytosis, 2 of 13 due to drug intolerance, and 1 of 13 due to an unrelated condition might indicate a lower tolerance to deferiprone in FA than in thalassemia.19,20 From Table 2 we deduced that the mild regimen of chelation used for up to 6 months on the remaining 9 FA patients was seemingly safe. Nonetheless, despite the apparent lack of statistically significant hematologic changes impaired by moderate oral chelation, we noted a trend of mild but steady decrease in blood iron–associated parameters. This calls for a close surveillance in future trials aimed at optimizing treatment.

We also noticed that a moderate chelation treatment can significantly shift the range of R2* (s−1) measured values in dentate nuclei of FA patients from a range of 16.8 s−1 to 21.2 s−1 to a range of 15.4 s−1 to 17.1 s−1, the latter of which is within the R2* margins determined empirically for a cohort of age-matched non-FA subjects, similar to what has been reported earlier.10 The most substantial and statistically significant shift was attained by the 3 patients with highest initial R2* (G-I in Figure 2). However, with the present information, one is not in a position to attach a therapeutic value to the chelator-evoked shifts in R2*. For that purpose it is necessary to establish normal and pathologic ranges of R2* in larger controlled studies.

This leaves open the question of whether, after attaining steady R2* levels, the drug treatment should be further moderated or, on the other hand, whether iron reinforcement should be used as a means to alleviate the mild hypoferemia-hypoferritinemia. In that respect, clinical experience (S.G. and A.M., May 2006, unpublished) showed that oral iron supplementation exacerbated ataxia symptoms in FA patients. Moreover, in vivo studies with frataxin-deficient Drosophila indicated a higher susceptibility of flies to iron-driven oxidative stress.53

However, most importantly and particularly serendipitous were the observations indicating improvement with respect to constipation, incontinence, manipulative dexterity, fluency of speech, some subjective signs of neuropathy, and even ataxic gait (Table 1). The modest but significant changes were observed in ICARS, particularly in the youngest patients. Although these observations are of an objective nature, they could not be correlated with MRI measurements because of the small sample and short period of treatment. Therefore, results should be regarded with caution until supplemented with comprehensive placebo-controlled studies that should address the different neuromotor properties and cardiac function in a quantitative manner. Moreover, this open-label single-arm study was limited to DFP used in conjunction with idebenone, to a period of 6 months, and to adolescents with a focus on brain MRI and preliminary neuromotor functions. Therefore, it remains to be confirmed by long-term studies that should incorporate DFP alone and in combination with idebenone as well as with chelators with better safety profiles for young populations, such as deferasirox.

The change in R2* values and ensuing clinical results of chelation provide some clues as to the pharmacologic modus operandi of DFP as possible scavenger of potentially toxic iron and/or as a vehicle for bypassing frataxin underexpression and supporting ISP formation. A possible role of idebenone in the present studies cannot be overlooked. Studies carried out in animal cell models deficient in frataxin have clearly indicated that idebenone supplementation compensates for the e-chain respiratory deficiency,41,54,55 whereas iron chelators rescue cells from toxic iron accumulating in mitochondria and promoting oxidative damage.14,18,48 These findings have been further strengthened in frataxin-deficient yeasts that attained iron homeostasis by inducing frataxin expression54 and overcome oxidative stress by overexpressing mitochondrial ferritin.55 In the clinical setting, raising brain erythropoietin levels by chelation-mediated activation of HIF (via prolyl-hydroxylase inhibition)56 and thereby inducing frataxin expression57 can be envisioned as a neuroprotective maneuver conferred by regional iron chelation. Such a mechanism raises the prospects of prophylactic chelation as a means to prevent impending damage by iron and for reversing iron-induced oxidative injury in at least some sensory neurons of the central nervous system, primarily at the early stages of FA and other diseases of NBIA.13

Although this study dealt with chelation of iron accumulated in a specific brain area, it also has implications for diseases of regional iron accumulation in which relocation of iron per se might be of therapeutic value, as in the anemia of chronic inflammation/disease.3 In that case, a chelator-mediated transfer of iron from reticuloendothelial cells to plasma apotransferrin, as indicated in earlier chelation studies,30 might provide an artificial bypass for the obstructed physiologic iron exit-pathway associated with hepcidin–down-regulated ferroportin.58

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this article.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Note added in proof.

The alternate mode of action proposed for deferiprone as a stimulator of hypoxia-inducible factor and thereby as an inducer of frataxin expression is supported by the recent study of Oktay Y., et al.59

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by F. Girard (GE-Health Care Technology Europe), DRC-APHP, Association Francaise contre la Myopathie (AFM), Israel Science Foundation (ISF), and AFIRN. We thank Dr Nir Navot for his interest in the work and Prof U. Motro for statistical advice.

Authorship

Contribution: N.B. and F.B. performed MRI studies; K.H.L.Q.S. coordinated patients and performed laboratory tests; A.R. performed laboratory tests; A.L.-W. performed computing MRI analysis; S.G. performed pediatric hematology follow-up; D.S. performed echocardiography; J.-C.T. designed the clinical trial and performed statistical analysis; A.M. designed and supervised the trial, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; and Z.I.C. designed the project, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

A.M. and Z.I.C. initiated the studies and had equal contributions.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Z. Ioav Cabantchik, Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, Hebrew University, Safra Campus-Givat Ram, Jerusalem 91904, Israel; e-mail: ioav@cc.huji.ac.il.

![Figure 3. Absolute and relative changes in R2* of individual FA patients after a 6-month treatment with DFP. The boxes represent the change in R2* constants (s−1) attained between 0 and 6 months of treatment with DFP (values taken from Figure 2), with the thick line representing the value at the end of treatment. The dotted lines represent the respective mean R2* values of 18.3 ± 1.6 s−1 and 15.7 ± 0.7 s−1 obtained at 0 and 6 months, respectively. The mean R2* values and the individual R2* values for each patient at 0 and 6 months were significantly different (P < .002; Anova test). The inset depicts the percentage decrease in R2* (calculated as [R2* {month 0} − R2* {month 6}]/[R2* {month 0}] ×100) versus the initial R2* (month-0 treatment) that yielded by linear regression analysis a slope of 4.2 ± 0.90 (r = 0.87, n = 9, P < .003).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/110/1/10.1182_blood-2006-12-065433/2/m_zh80130703220003.jpeg?Expires=1767876154&Signature=AGdKzIjX90p2PIF6N3dXTVYZPPrLYRtyJQnpMXMQynHBNElTpMsw9YReMCx35ll3urolV9X0i~iWwDgen5e1sldSx7vwOEJlhPuYuRc6Yyz3GJWsCPTIij57vn-2LC58nhuJf7DROKopnlAuGdba1iEAUNGVK~R5MDddWL735a6A1jJenJvNbty0USXbINFQoDcQsAlEZmQKi6j-NyJ5Th1T1J-DUP~gIAc8QdvMCX33sGJatTNslGpGAOlwTBjh-HJEqTlFZHGC2CK5IumI~vMWBpryOqNSRv3tBi6XkSUPHe08~xU4zuyPbTctrJyB9QakeqF2lIHxQLpeiFeUTg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)