Abstract

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) and chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL) comprise a spectrum of indolent to aggressive diseases characterized by unexplained, persistent hypereosinophilia. These disorders have eluded a unique molecular explanation, and therapy has primarily been oriented toward palliation of symptoms related to organ involvement. Recent reports indicate that HES and CEL are imatinib-responsive malignancies, with rapid and complete hematologic remissions observed at lower doses than used in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). These BCR-ABL–negative cases lack activating mutations or abnormal fusions involving other known target genes of imatinib, implicating a novel tyrosine kinase in their pathogenesis. A bedside-to-benchtop translational research effort led to the identification of a constitutively activated fusion tyrosine kinase on chromosome 4q12, derived from an interstitial deletion, that fuses the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α gene (PDGFRA) to an uncharacterized human gene FIP1-like-1 (FIP1L1). However, not all HES and CEL patients respond to imatinib, suggesting disease heterogeneity. Furthermore, approximately 40% of responding patients lack the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion, suggesting genetic heterogeneity. This review examines the current state of knowledge of HES and CEL and the implications of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA discovery on their diagnosis, classification, and management. (Blood. 2004;103:2879-2891)

Introduction

Protean biologic and clinical presentations characterize idiopathic hypereosinophilia (HES). HES is similar to other diseases given the moniker “diagnosis of exclusion,” in that limited understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease has hampered therapeutic advances. The demonstration of increased myeloblasts or clonality or the development of either granulocytic sarcoma or acute myeloid leukemia helps clarify the origin of some cases of chronic eosinophilic leukemia.1 In a subset of patients, hypereosinophilia is related to excessive secretion of eosinophilopoietic cytokines from a clonal population of lymphocytes.2 The identification of FIP1-like-1–platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (FIP1L1-PDGFRA) in cases of HES/CEL adds to a growing list of activated fusion tyrosine kinases linked to the pathogenesis of chronic myeloproliferative disorders.3 It is unique, however, because it is the first description of a gain-of-function fusion protein resulting from a cryptic interstitial deletion between genes rather than a reciprocal chromosomal translocation. The FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion protein transforms hematopoietic cells, and its kinase activity is inhibited by imatinib at a cellular 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) 100-fold lower than BCR-ABL.3 Acquisition of an imatinib resistance mutation in the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–binding domain of PDGFRA in a relapsed patient previously responsive to imatinib supports a critical role for FIP1L1-PDGFRα in the pathogenesis of disease and demonstrates that FIP1L1-PDGFRα is the therapeutic target of imatinib.3 The identification of this novel molecular target in HES and CEL patients will help refine genotype-phenotype correlations in these diseases and should aid basic research of the biologic pathways involved in eosinophil proliferation, differentiation, and signaling.

Epidemiology

HES is predominantly a disease of men (male-female ratio, 9:1) and is usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 years and 50 years.4 In one series of 50 patients, the mean age at onset was 33 years and the mean duration of disease was 4.8 years (range, 1-24 years) during the time period the patients were followed.4 Rare cases in infants and children have also been described.5-7

Current classification

In 1968 Hardy and Anderson coined the term “hypereosinophilic syndrome” to describe patients with prolonged eosinophilia of unknown cause.8 Chusid et al in 1975 used 3 diagnostic criteria for HES that are still utilized today: (1) persistent eosinophilia of 1.5 × 109/L (1500/mm3) for longer than 6 months; (2) lack of evidence for parasitic, allergic, or other known causes of eosinophilia; and (3) signs and symptoms of organ involvement.9 In the recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification, a diagnosis of HES or CEL requires exclusion of reactive causes of eosinophilia (Table 1), malignancies in which eosinophilia is reactive (Table 1) or part of the neoplastic clone, and T-cell disorders associated with abnormalities of immunophenotype and cytokine production, with or without evidence of lymphocyte clonality.10 CEL has traditionally been distinguished from HES by the presence of increased peripheral blood (more than 2%) or marrow (5%-19%) blasts or the demonstration of a clonal cytogenetic abnormality in the myeloid lineage.10 However, this categoric distinction is now called into question by the identification of FIP1L1-PDGFRA in both forms of the disease (see “Implications of FIP1L1-PDGFRA for the diagnosis, classification, and treatment of eosinophilic disorders”).

One method for establishing a diagnosis of CEL is demonstration of eosinophil clonality; however, this is frequently not assessed or is difficult to confirm. Methods for demonstrating clonality include fluorescence in situ hybridization11 or cytogenetic analysis of purified eosinophils12 and, also, X chromosome inactivation analysis in women.13,14 X inactivation–based assessment of clonality is of limited value in HES because most patients are male. To avoid the emphasis placed on demonstrating clonality of eosinophils, Brito-Babapulle has advocated that, in cases of clonal eosinophilia, it is sufficient to demonstrate only that eosinophils are part of a clonal bone marrow disorder and not necessarily part of the malignant clone, with treatment tailored to the underlying disease.15 In this scheme, blood eosinophilia is divided into 3 categories: reactive (nonclonal eosinophilia), clonal disorders of the bone marrow associated with eosinophilia, and HES, which remains a diagnosis of exclusion.15

Prior reviews have discussed the difficulty in using abnormal eosinophil morphology (eg, cytoplasmic hypogranularity or vacuolization, abnormal lobation, ring nuclei) to reliably distinguish reactive from clonal eosinophilia because these cytologic changes may be present in both conditions.15-17 Roufosse et al have proposed that disease presentations with CML-like features be segregated into a “myeloproliferative variant” of HES.18 Clinical and laboratory features associated with this variant include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, anemia, thrombocytopenia, bone marrow dysplasia or fibrosis, and elevated levels of cobalamin. This is in contrast to a “lymphocytic variant” or T-cell–mediated HES (discussed in “T-cell–mediated HES”), which typically follows a more benign course and is usually manifested primarily by skin disease.18 Some patients exhibit overlapping characteristics of both variants. Although such groupings may correspond to biologic subsets of HES, evaluation of a large cohort of patients is required to validate their prognostic relevance.

Clinicopathologic manifestations

In one large series, eosinophilia was discovered incidentally in 12% of patients.4 The most common presenting signs and symptoms were weakness and fatigue (26%), cough (24%), dyspnea (16%), myalgias or angioedema (14%), rash or fever (12%), and rhinitis (10%).4 Table 2 shows the cumulative frequency of organ involvement in 105 patients previously compiled from 3 series.4,17,19-21

Hematologic findings

Although persistent eosinophilia without a clinically identifiable cause is the sine qua non of HES, the hematologic picture can vary. Relatively modest elevations in the leukocyte count (eg, 20-30 × 109/L [20 000-30 000/mm3]) with peripheral eosinophilia in the range of 30% to 70% are commonly observed,9 but significantly higher leukocyte counts have also been reported.19,20 Neutrophilia, basophilia, myeloid immaturity, and both mature and immature eosinophils with varying degrees of dysplasia may be found in the peripheral blood or bone marrow.19,22 In one series, anemia was present in 53% of patients, thrombocytopenia was more common than thrombocytosis (31% versus 16%), and bone marrow eosinophilia ranged from 7% to 57% (mean, 33%).22 Charcot-Leyden crystals were frequent marrow findings, whereas increased blasts and myelofibrosis were less often observed.22

Cardiac disease

The multistep process of cardiac injury illustrates some of the pathophysiologic mechanisms contributing to organ damage in HES (previously reviewed by Fauci et al4 and Weller and Bubley21 ). In the initial necrotic stage, cardiac disease may be initiated by eosinophil damage to the endocardium, with local platelet thrombus subsequently leading to formation of mural thrombi that have the potential to embolize (thrombotic stage). The contents of eosinophil granules, including major basic protein and eosinophilic cationic protein, may promote endothelial damage and hypercoagulablity, enhancing the thromboembolic risk.23,24 In the later fibrotic stage, organization of thrombus can lead to fibrous thickening of the endocardial lining and, ultimately, restrictive cardiomyopathy.4,21 Valvular insufficiency in HES is commonly related to mural endocardial thrombosis and fibrosis involving leaflets of the mitral or tricuspid valves.25-27 Table 2 lists manifestations of HES that have been reported in hematologic, cardiac, and other organ systems.

T-cell–mediated HES

A proportion of HES cases exhibit expansion of abnormal lymphocyte populations. Immunophenotypic features include double-negative, immature T cells (eg, CD3+CD4-CD8-) or absence of CD3 (eg, CD3-CD4+), a normal component of the T-cell receptor complex.91-93 In patients with T-cell–mediated hypereosinophilia with elevated immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, lymphocyte production of interleukin-5 (IL-5)—and in some cases IL-4 and IL-13—suggests that these T cells have a helper type 2 (Th2) cytokine profile.18,91,93-95 In a study of 60 patients recruited primarily from dermatology clinics, 16 had a unique population of circulating T cells with an abnormal immunophenotype.2 Clonal rearrangement of T-cell receptor genes was demonstrated in half of these individuals (8 of 60 total patients). The abnormal T cells secreted high levels of interleukin-5 in vitro and displayed an activated immunophenotype (eg, CD25 and/or HLA-DR expression). One patient during study and 3 at follow-up were diagnosed with T-cell lymphoma or Sézary syndrome, indicating that T cells in some HES patients have neoplastic potential. The factors that contribute to malignant transformation in T-cell–associated HES require further characterization. In some cases, accumulation of cytogenetic changes in T cells and proliferation of lymphocytes with the CD3-CD4+ phenotype have been observed.95-97 It is currently unknown whether subsets of T-cell–associated HES cases also express the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion.

Cytogenetic and molecular features of hematologic malignancies with eosinophilia

Several hematologic malignancies are associated with eosinophilia. Eosinophilia is thought to result from the production of cytokines (eg, IL-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF]) from malignant cells in T-cell lymphomas,98 Hodgkin disease,99 and acute lymphoblastic leukemias.100,101 In some cases, isolated eosinophilia may herald the initial diagnosis or relapse of these conditions.

Over the last 3 decades, the list of chromosomal abnormalities in cases reported as HES or CEL has grown (reviewed by Bain102 ). However, a unique clonal karyotype has not been associated with these diseases, and most patients exhibit a normal karyotype by conventional cytogenetics. Although trisomy 8 is frequently detected in these eosinophilic disorders,103-106 it is also observed in other hematologic malignancies. Three HES case reports have described balanced reciprocal translocations within or near the chromosome 4q12 locus of the PDGFRA and KIT tyrosine kinases: t(3;4)(p13;q12),107 t(4;7)(q11;q32),108 and t(4;7)(q11;p13).109 The genes involved in these translocations were not identified. In a recent report, a 6-year-old girl with hypereosinophilia presented with a t(5;9)(q11;q34) constitutional translocation, involving genes for the ABL tyrosine kinase and possibly granzyme A on chromosome 5.7 In this case, no mention was made of the use of imatinib.

Eosinophils have been found to be part of the malignant clone in systemic mastocytosis,110 CML and other chronic myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs), and in specific subtypes of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The best-characterized examples in the French-American-British classification of AML are M4Eo inv(16)(p13q22) or t(16;16)(p13;q22),111 resulting in chimeric fusion of the CBFβ and MYH11 genes, and M2 t(8;21)(q22;q22),112 which links the AML-1 and ETO genes. Other abnormal karyotypes reported in AML with eosinophilia include monosomy 7,113 trisomy 1,114 t(10;11)(p14;q21),115 t(5;16)(q33;q22),116 and t(16;21)(p11;q22).117 The latter 2 may represent chromosome 16 variants with an underlying cryptic fusion gene. Eosinophil clonality has been demonstrated in cases of eosinophilic myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) with t(1;7) or dic(1;7) karyotypes.11,118 Eosinophilia is also a feature of acute and chronic hematologic malignancies with rearrangements involving transcription factor ETV6 (ETS translocation variant 6, TEL) on chromosome 12p13. Examples include the ETV6-ABL fusion in t(9;12)(q34;p13) AML119 and, also, the small subset of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia patients with t(5;12)(q33;p13), which fuses platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFRβ) on chromosome 5q33 to ETV6.120 In this latter disease, imatinib produces clinical remissions by inhibiting the deregulated activity of the fusion tyrosine kinase.121 Proliferation of eosinophils in some AML, MPD, and MDS cases is associated with rearrangements involving the long arm of chromosome 5 (eg, 5q31-33) where several genes encoding eosinophilic cytokines reside.122-124 In a study of 9 patients with MPD or mixed MDS/MPD and a translocation involving 5q31-33, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) unmasked disruption of the PDGFRB gene in 6 cases.125 The translocations included t(1;5)(q21;q33), t(1;5)(q22;q31), t(1;3;5)(p36;p21;q33), t(2;12;5)(q37;q22;q33), t(3;5)(p21;q31), and t(5;14)(q33;q24). Eosinophilia was noted in 3 of these patients and noted in an additional case at the time of transformation to AML.125 Recent cloning of the t(1;5)(q23;q33) breakpoint revealed that PDGFRB is fused to the novel partner protein myomegalin.126 In a subset of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias, translocation of the IL-3 gene on chromosome 5q31 to the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene on chromosome 14q32 is typically associated with eosinophilia.127 In the “stem cell” myeloproliferative disorders, mutation in a pluripotent hematopoietic progenitor results in a spectrum of diseases including T- or B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, bone marrow myeloid hyperplasia, and eosinophilia. These poor-prognosis disorders are related to recurrent breakpoints on chromosome 8p11 that involve translocation of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) gene to 5 currently identified partner loci: FOP at 6q27,128 CEP110 at 9q33,129 FIM/ZNF198 at 13q12,130 BCR at 22q11,131 and the human endogenous retrovirus gene (HERV-K) at 19q13.132 Before attributing eosinophilia to HES or CEL, these various hematologic malignancies should be given diagnostic consideration.

Prognosis

A prior review of 57 HES cases included reports published between 1919 and 1973.9 The median survival was 9 months, and the 3-year survival was only 12%.9 These patients generally had advanced disease, with congestive heart failure accounting for 65% of the identified causes of death at autopsy. In addition to the development of cardiac disease, peripheral blood blasts or a white blood cell (WBC) count more than 100 ×109/L (100 000/mm3) were associated with a poor prognosis.9 A later report of 40 HES patients observed a 5-year survival rate of 80%, decreasing to 42% at 15 years.20 In this cohort, poor prognostic factors included the presence of a concurrent myeloproliferative syndrome, lack of response of the hypereosinophilia to corticosteroids, existence of cardiac disease, male sex, and the height of eosinophilia.20 Modern diagnostic methods and better treatment for cardiovascular disease probably contribute to improved survival.

Current treatment

In patients with persistent eosinophilia and organ damage due to reactive causes or clonal bone marrow disease, therapy should be directed to the underlying disorder. Some treatment algorithms have incorporated serial monitoring of eosinophil counts, evaluation of clonality (eg, T-cell–receptor gene rearrangement, immunophenotyping), bone marrow aspiration and biopsy with cytogenetics, and directed organ assessment (eg, echocardiography) to identify occult organ disease and alternative causes of eosinophilia that may slowly emerge after an initial diagnosis of HES.15,21 In patients with HES, corticosteroids (1 mg/kg/d) are indicated for organ disease and are useful for eliciting rapid reductions in the eosinophil count.4,21,133 Lack of steroid responsiveness warrants consideration of cytotoxic therapy. Hydroxyurea is an effective first-line chemotherapeutic for HES4,21,133 ; some benefit has also been reported for second-line agents including vincristine,134-136 pulsed chlorambucil,21 cyclophosphamide,137 and etoposide.138,139 Interferon-α (IFN-α) can elicit long-term hematologic and cytogenetic responses in HES and CEL patients resistant to other therapies, including prednisone and hydroxyurea.109,140-145 Some have advocated its use as initial therapy for these diseases.144 Remissions have been associated with improvement in clinical symptoms and organ disease, including hepatosplenomegaly,140,144 cardiac and thromboembolic complications,109,141 mucosal ulcers,143 and skin involvement.145 IFN-α exerts pleiotropic effects including inhibition of eosinophil proliferation and differentiation.146 Inhibition of IL-5 synthesis from CD4+ helper T cells may be relevant to its mode of action in T-cell–mediated forms of HES.147 IFN-α may also act more directly via IFN-α receptors on eosinophils, suppressing release of mediators including cationic protein, neurotoxin, and interleukin-5.148 Responses to cyclosporin A149,150 and 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine have also been reported in HES.151

Bone marrow/peripheral blood stem cell allogeneic transplantation has been attempted in patients with aggressive disease. Disease-free survival ranging from 8 months to 5 years has been reported152-156 with one patient relapsing at 40 months.157 Allogeneic transplantation using nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens has been reported in 3 patients, with remission duration of 3 to 12 months at the time of last reported follow-up.158,159 Despite success in selected cases, the role of transplantation in HES is not well established. Transplantation-related complications including acute and chronic graft versus host disease as well as serious infections have been frequently observed.160,161

Advances in cardiac surgery have extended the life of patients with late-stage heart disease manifested by endomyocardial fibrosis, mural thrombosis, and valvular insufficiency.4,21 Mitral and/or tricuspid valve repair or replacement26,35-37,162 and endomyocardectomy for late-stage fibrotic heart disease37,163 can improve cardiac function. Bioprosthetic devices are preferred over their mechanical counterparts because of the reduced frequency of valve thrombosis.

Leukapheresis can elicit transient reductions in high eosinophil counts but is not an effective maintenance therapy.164-166 Similar to other myeloproliferative disorders, splenectomy has been performed for hypersplenism-related abdominal pain and splenic infarction but is not considered a mainstay of treatment.19,167 Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents have shown variable success in preventing recurrent thromboembolism.19,47,50,168

Imatinib in HES

Table 3 summarizes published case reports and series of patients with hematologic malignancies associated with eosinophilia who were treated with imatinib. The first case of imatinib treatment in HES was reported in 2001.169 The patient was resistant or intolerant to prior therapies including corticosteroids, hydroxyurea, and IFN-α. He was treated with imatinib based on the drug's efficacy in CML, with the hypothesis that the 2 diseases may share a common pathogenetic mechanism. The patient achieved a rapid and complete hematologic remission after taking 100 mg imatinib daily for 4 days. Complete disappearance of peripheral eosinophils occurred by day 35. Imatinib was decreased to 75 mg daily for headaches, which still effectively controlled eosinophil levels.

A subsequent report included 5 HES patients treated with 100 mg imatinib daily.170 Four male patients with normal serum levels of interleukin-5 achieved complete hematologic remissions. One female patient with high levels of serum interleukin-5 did not respond to imatinib. All patients who responded were able to discontinue other treatments.

A third report described a 54-year-old man with HES and organ involvement including splenomegaly, skin, cardiac, and central nervous system disease.167 He was resistant to steroids and chemotherapy, including 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine and cytosine arabinoside. Before treatment, the WBC count was 9.7 × 109/L (9700/mm3) with 68% eosinophils. After 18 days of imatinib (100 mg daily), the patient achieved a complete hematologic remission with a WBC count of 3.9 × 109/L (3900/mm3) and 0% eosinophils. His hematologic response was accompanied by marked symptomatic improvement.

Another study reported the efficacy of 100 to 400 mg imatinib daily in 5 HES patients and 2 patients with a diagnosis reported as eosinophilia-associated chronic myeloproliferative disorder (eos-CMD).171 At a median follow-up of 17 weeks, 1 eos-CMD and 2 HES patients achieved complete clinical remissions, and an additional HES patient achieved a partial remission. Screening for known targets of imatinib, including BCR-ABL, or mutations in the coding exons of KIT and PDGFRB was negative. In contrast to the earlier report where complete remitters had normal serum interleukin-5 levels, the current group of responders had high serum levels. These disparate findings demonstrate that levels of this eosinophil-stimulating cytokine are not necessarily predictive of imatinib responsiveness in HES patients. Although imatinib was generally well tolerated, one responding HES patient experienced cardiogenic shock within the first week of treatment with a marked decrease in the left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction. Endomyocardial biopsy revealed eosinophilic myocarditis with evidence of eosinophil infiltration, degranulation, and myocyte damage. The patient was successfully treated with high-dose corticosteroids. LV function recovered, and the patient was restarted on imatinib and achieved a hematologic remission. More data are needed to evaluate the role of prophylactic steroids in HES patients with cardiac disease who receive imatinib treatment.

An additional cohort of 9 symptomatic HES patients (6 male; median age, 50) was treated with imatinib starting at 100 mg daily.172 They had received an average of 3 prior therapies. With median follow-up of 13 weeks, 4 male patients achieved a complete remission. Three exhibited response within the first 2 weeks of therapy, while the fourth required a dose increase to 400 mg daily at day 28 to attain a normal eosinophil count. Overall, treatment was well tolerated, with primarily grade 1 toxicities previously associated with imatinib reported.

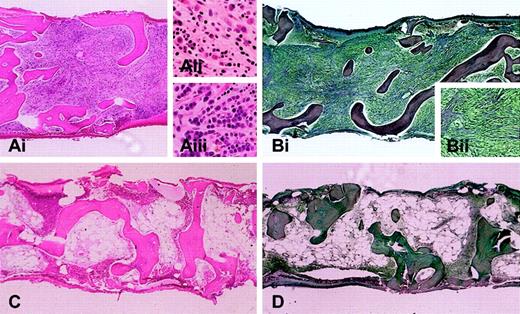

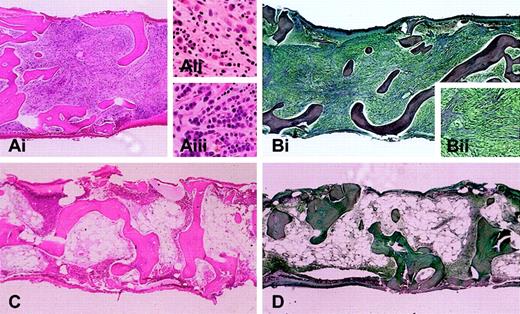

The largest study described 16 patients, including 11 treated with imatinib.3 At presentation, the median eosinophil count was 14.5 × 109/L (14500/mm3) (range, 4.96 × 109/L to 53 × 109/L [4960/mm3 to 53000/mm3]). Nine of the treated patients had normal karyotypes. One CEL patient had a clonal cytogenetic abnormality t(1;4)(q44;q12), and one patient with AML arising from CEL had a complex karyotype, including trisomies 8 and 19, add2q, and del6q. Hematologic responses were observed in 10 of 11 HES patients treated with imatinib at doses of 100 to 400 mg daily. The median time to response was 4 weeks (range, 1 to 12 weeks). Nine of the 10 patients demonstrated sustained hematologic responses (lasting at least 3 months), with a median duration of 7 months at the time of publication (range, 3 to 15 months). One patient had a transient response lasting several weeks and failed to derive benefit from an increase in the imatinib dose. Figure 1 shows a bone marrow biopsy from the CEL/AML patient with the complex karyotype before imatinib treatment and at the time of hematologic remission following 3 months of therapy.

Bone marrow biopsy from a patient with AML and myelofibrosis arising from chronic eosinophilic leukemia. Bone marrow biopsies are shown before (A-B) and after (C-D) imatinib treatment. (A) Marrow biopsy section (Ai; hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, × 4) is hypercellular with scattered eosinophils (Aii; original magnification, × 20) and columnar arrays of immature myeloid cells (Aiii; original magnification, × 20). (B) Reticulin stain highlights severe fibrosis (magnified view, Bii; original magnification, × 10). After 3 months of imatinib therapy, (C) marrow biopsy reveals marked hypocellularity without increased immature myeloid cells or eosinophils, and (D) reticulin stain shows markedly diminished fibrosis (original magnification, × 4 for panels C and D). After an additional 3 months, the patient relapsed with bone marrow findings similar to those in panels A and B. Screening of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion at the time of relapse revealed the interval development of an imatinib resistance mutation (T674I) within the PDGFRA gene.

Bone marrow biopsy from a patient with AML and myelofibrosis arising from chronic eosinophilic leukemia. Bone marrow biopsies are shown before (A-B) and after (C-D) imatinib treatment. (A) Marrow biopsy section (Ai; hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, × 4) is hypercellular with scattered eosinophils (Aii; original magnification, × 20) and columnar arrays of immature myeloid cells (Aiii; original magnification, × 20). (B) Reticulin stain highlights severe fibrosis (magnified view, Bii; original magnification, × 10). After 3 months of imatinib therapy, (C) marrow biopsy reveals marked hypocellularity without increased immature myeloid cells or eosinophils, and (D) reticulin stain shows markedly diminished fibrosis (original magnification, × 4 for panels C and D). After an additional 3 months, the patient relapsed with bone marrow findings similar to those in panels A and B. Screening of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion at the time of relapse revealed the interval development of an imatinib resistance mutation (T674I) within the PDGFRA gene.

The molecular basis for response in most patients was inhibition of a novel fusion tyrosine kinase, FIP1L1-PDGFRα, in which a newly described human gene, FIP1-like-1 (FIP1L1), is fused to the gene encoding platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA).3 The FIP1L1 gene encodes a protein that is homologous to a previously characterized Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein, Fip1, a synthetic lethal component of the mRNA polyadenylation apparatus.173 The fusion gene is generated by an interstitial deletion on chromosome 4q12 rather than a reciprocal translocation.3 FIP1L1-PDGFRA was present in 9 (56%) of 16 HES patients. In patients for whom FIP1L1-PDGFRA testing was performed, the fusion was detected with a similar frequency in treated (5 of 10) and untreated (4 of 6) patients.3 All 5 patients with the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion responded to imatinib.3 However, an additional 4 patients with durable responses to imatinib lacked FIP1L1-PDGFRA, indicating that an as yet unidentified target of imatinib is responsible for HES in these cases.3 To date, no primary treatment failures to imatinib have been reported in patients with the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion.

The FIP1L1-PDGFRA genotype may cosegregate with a clinical phenotype including myeloproliferative-like HES (HES-MPD), tissue fibrosis, and increased serum tryptase levels.174,175 The FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion was identified in all 7 HES-MPD patients with elevated serum tryptase levels (all were treated with imatinib and responded)175 ; in an earlier companion study, the fusion was not detected in 4 HES patients with normal serum tryptase or 2 patients with familial eosinophilia. FIP1L1-PDGFRA may also be related to the pathogenesis of eosinophilic subsets of systemic mastocytosis (SM). Deletion of the CHIC2 locus, a surrogate for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion, was detected in imatinib-responsive patients diagnosed with systemic mastocytosis (SM) and eosinophilia but not in 2 other patients with SM and the KIT Asp816Val (D816V) mutation who exhibited no response to imatinib.176

Currently, limited data are available regarding imatinib's ability to reverse eosinophil-related organ damage. Among 3 HES-MPD patients with endomyocardial fibrosis and congestive heart failure, there was no improvement in cardiac disease despite complete hematologic responses to imatinib.175 However, significant improvement of respiratory symptoms associated with clearing of interstitial infiltrates on chest computed tomography (CT)171,175 and normalization of pulmonary function testing have been reported.175 We and others have demonstrated reversal of myelofibrosis (Figure 1).175

Molecular biology of FIP1L1-PDGFRA

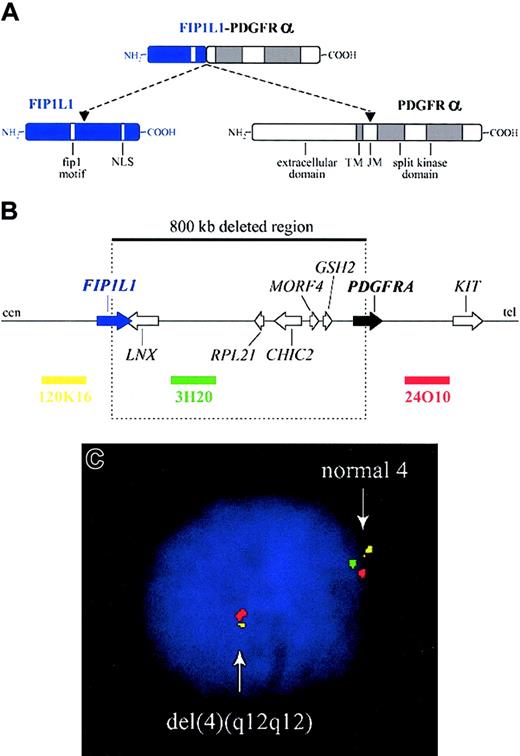

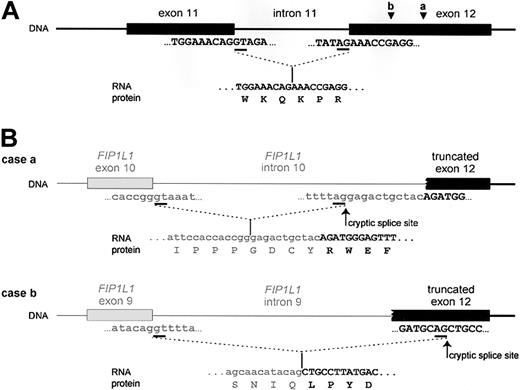

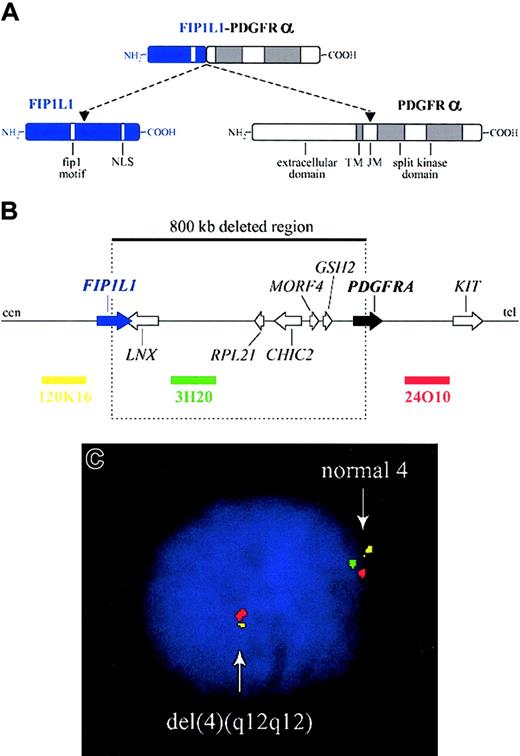

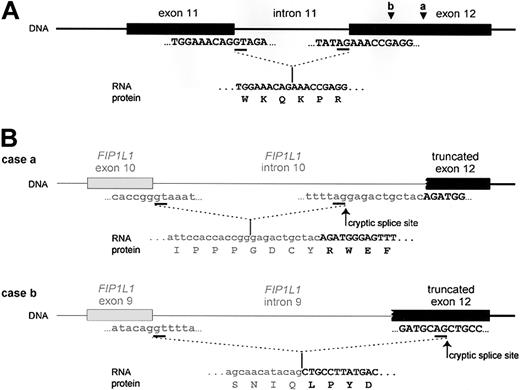

The FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene is created by the del(4)(q12q12), an 800-kb deletion on chromosome 4q12 (Figure 2).3 The deletion is not visible using standard cytogenetic banding techniques and explains why most HES patients with the fusion have an apparently normal karyotype. One imatinib-responsive HES patient with a t(1;4)(q44;q12) ultimately led to the identification of the fusion gene, but in retrospect the translocation was merely a “stalking horse” for the del(4)(q12q12) that gives rise to the fusion gene.3 The deletion disrupts the FIP1L1 and PDGFRA genes and fuses the 5′ part of FIP1L1 to the 3′ part of PDGFRA.3 In each patient the breakpoints in FIP1L1 and PDGFRA are different, but the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusions are always in frame.3 The breakpoints in FIP1L1 are scattered over a region of 40 kb (introns 7-10), whereas the breakpoints in PDGFRA are restricted to a very small region that invariably involves PDGFRA exon 12.3 As the 5′ part of exon 12 of PDGFRA is deleted, splicing of FIP1L1 exons to the truncated exon 12 of PDGFRA occurs by use of cryptic splice sites within exon 12 of PDGFRA or in introns of FIP1L1 (Figure 3).3,175

Fusion of FIP1L1 to PDGFRA. (A) Schematic representation of the FIP1L1, PDGFRα, and FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion proteins. NLS indicates nuclear localization signal; TM, transmembrane region; and JM, juxtamembrane region. (B) Schematic representation of the 4q12 chromosomal region around the FIP1L1 and PDGFRA genes. The 800-kb deletion, resulting in the fusion of the 5′ part of FIP1L1 to the 3′ part of PDGFRA, and the location of 3 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) probes (RPCI11-120K16, RPCI11-3H20, and RPCI11-24O10) are indicated. cen indicates centromeric side; and tel, telomeric side. (C) Detection of the del(4)(q12q12) in an HES case by interphase FISH using the BAC probes shown in panel B. Absence of probe 3H20 and presence of the 2 flanking probes is indicative of the presence of this specific deletion on one of the chromosomes 4.

Fusion of FIP1L1 to PDGFRA. (A) Schematic representation of the FIP1L1, PDGFRα, and FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion proteins. NLS indicates nuclear localization signal; TM, transmembrane region; and JM, juxtamembrane region. (B) Schematic representation of the 4q12 chromosomal region around the FIP1L1 and PDGFRA genes. The 800-kb deletion, resulting in the fusion of the 5′ part of FIP1L1 to the 3′ part of PDGFRA, and the location of 3 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) probes (RPCI11-120K16, RPCI11-3H20, and RPCI11-24O10) are indicated. cen indicates centromeric side; and tel, telomeric side. (C) Detection of the del(4)(q12q12) in an HES case by interphase FISH using the BAC probes shown in panel B. Absence of probe 3H20 and presence of the 2 flanking probes is indicative of the presence of this specific deletion on one of the chromosomes 4.

Fusion of FIP1L1 to PDGFRA involves the use of cryptic splice sites. (A) Splicing of exon 11 to exon 12 as it occurs in wild-type PDGFRA. (B) Splicing of FIP1L1 exons to the truncated exon 12 of PDGFRA as observed in 2 different HES patients. As the normal splice site in front of exon 12 is deleted, cryptic splice sites in the introns of FIP1L1 (as in case a) or within exon 12 (as in case b) are used to generate in-frame FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusions. As a result, the fusion protein sometimes contains a few extra amino acids derived from an intronic sequence of FIP1L1 (as in case a). Sequences from FIP1L1 are shown in lowercase letters and in gray; PDGFRA sequences are shown in capital letters and in black. Introns are depicted as lines; exons are shown as blocks. Splice sites are underlined in the sequence. The spliced RNA sequence and corresponding protein sequence are shown under the DNA. Cryptic splice sites are indicated with an arrow. Arrowheads indicate where the breakpoints are located in exon 12 of PDGFRA in cases a and b.

Fusion of FIP1L1 to PDGFRA involves the use of cryptic splice sites. (A) Splicing of exon 11 to exon 12 as it occurs in wild-type PDGFRA. (B) Splicing of FIP1L1 exons to the truncated exon 12 of PDGFRA as observed in 2 different HES patients. As the normal splice site in front of exon 12 is deleted, cryptic splice sites in the introns of FIP1L1 (as in case a) or within exon 12 (as in case b) are used to generate in-frame FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusions. As a result, the fusion protein sometimes contains a few extra amino acids derived from an intronic sequence of FIP1L1 (as in case a). Sequences from FIP1L1 are shown in lowercase letters and in gray; PDGFRA sequences are shown in capital letters and in black. Introns are depicted as lines; exons are shown as blocks. Splice sites are underlined in the sequence. The spliced RNA sequence and corresponding protein sequence are shown under the DNA. Cryptic splice sites are indicated with an arrow. Arrowheads indicate where the breakpoints are located in exon 12 of PDGFRA in cases a and b.

FIP1L1-PDGFRα has also been discovered in the cell line EOL-1, derived from a patient with acute eosinophilic leukemia following hypereosinophilic syndrome. Imatinib and 2 other inhibitors of PDGFRα, vatalanib and THRX-165724, reduced the viability of EOL-1 cells and a prominent 110-kDa phosphoprotein, ultimately identified as FIP1L1-PDGFRα.177

FIP1L1 is a 520–amino acid protein that contains a region of homology to Fip1, a yeast protein with synthetic lethal function that is involved in polyadenylation.174,178 Similar proteins are found in plants, worm, fly, rat, and mouse. All share the well-conserved 42–amino acid “Fip1” motif (pfam domain no. PF05182; http://pfam.wustl.edu/cgi-bin/getdesc?acc=PF05182), which is also present in the FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion protein. The exact function of the human or mouse FIP1L1 protein is not known. Based on the abundance of FIP1L1 expressed sequence tags (ESTs) in the databases that are derived from different tissues and cell types, FIP1L1 is predicted to be under the control of a ubiquitous promoter.

Similar to other fusion tyrosine kinases, FIP1L1-PDGFRα is a constitutively active tyrosine kinase that transforms hematopoietic cells in vitro and in vivo.3,179 FIP1L1-PDGFRα phosphorylates itself and signal transducer and activator of transcription-5 (STAT5) but, in contrast with the native PDGFRα, does not activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway.3,180,181 The difference in MAPK signaling might be explained by the difference in subcellular localization, because PDGFRα is a transmembrane protein with ready access to farnesylated RAS, whereas FIP1L1-PDGFRα is predicted to be cytosolic. In support of this hypothesis, membrane attachment of PDGFRβ is critical for its ability to activate the MAPK pathway.182

The mechanism of constitutive activation of FIP1L1-PDGFRα tyrosine kinase activity is not well understood. It would be predicted, based on analysis of structure-function in all known fusion tyrosine kinases, including BCR-ABL,183 TEL-PDGFRβ,184 TEL-ABL,185 H4-PDGFRβ,186 HIP1-PDGFRβ,187 and TEL-JAK2,188 that FIP1L1 would contribute a homodimerization motif that serves to constitutively activate the PDGFRα kinase. However, we have not identified a dimerization motif within FIP1L1 that delineates it from all other known tyrosine kinase fusion partners in cancer.

The genetic analysis of multiple patients may provide a clue to the mechanism of activation. Most chromosomal translocations that result in fusion tyrosine kinases occur at highly variable locations within large introns. Although the genomic breakpoint is in essence unique for each patient, RNA splicing usually results in expression of identical fusion proteins. Consistent with this experience, the FIP1L1 genomic breakpoints are variable and may occur in several introns within the gene. However, the genomic breakpoints in PDGFRA are quite unusual, in that they all occur within exon 12.

How might conserved breakpoints within exon 12 contribute to constitutive activation of the PDGFRα kinase? Exon 12 of PDGFRA encodes a portion of the juxtamembrane domain that is known to serve an autoinhibitory function in the context of other receptor tyrosine kinases. Disruptions of this domain by missense mutations, in-frame insertions, or in-frame deletions result in constitutive activation of the respective tyrosine kinase. For example, juxtamembrane internal tandem duplications in FLT3 result in its constitutive activation in approximately 25% of cases of AML.189 Mutation of the juxtamembrane domain of KIT results in its constitutive activation in most cases of gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors.190 The juxtamembrane region of PDGFRβ contains a WW domain with an inhibitory function for kinase activity, and in-frame point mutations of the WW domain result in constitutive activation of the kinase.191 Furthermore, mutations in the WW domain of PDGFRα were identified in rare cases of gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors.192 To date, all cloned FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion genes result in a truncation of PDGFRα within the WW domain, suggesting that interruption of the WW domain contributes to the activation of FIP1L1-PDGFRα. Thus, a plausible hypothesis is that disruption of PDGFRA exon 12 within the WW domain, in combination with unregulated expression from the FIP1L1 promoter, are the pivotal events required for transformation of cells.

There are several important implications from the hypothesis that the interstitial deletion serves primarily to disrupt the autoinhibitory domain and fuses the kinase to a constitutively activated and unregulated promoter. First, it indicates that potential kinase gene partners need not have dimerization motifs but only an active promoter to contribute to pathogenesis of disease. Thus, deletions of varying sizes that each disrupt exon 12 of PDGFRA could involve a spectrum of genomically diverse genes 5′ of the kinase. This mechanism could even be invoked for very large and highly variable deletions. In imatinib-responsive HES without a detectable FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion, it will be important to analyze other potential partners for PDGFRα as well as similar mechanisms of activation of the other known imatinib-responsive tyrosine kinases.

Another important implication of these findings is that small interstitial chromosomal deletions that activate tyrosine kinases may also occur in other hematologic malignancies or solid tumors. Indeed, it is possible that the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene itself could be expressed in tumors from other tissue types. This hypothesis can be tested using modern techniques for high-density comparative genomic hybridization, among other strategies, to search for subcytogenetic deletions in the 5′ flanking region of all known receptor tyrosine kinases. It is also possible that small interstitial deletions can engender gain-of-function oncogenes involving other classes of genes. Efforts to identify such deletions in all tumor types is warranted, in part because there are convincing data that gain-of-function fusion proteins are candidates for molecularly targeted therapies such as imatinib.

One patient who initially responded to imatinib relapsed with an acquired T674I substitution in the PDGFRα kinase domain of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion. The mutation confers resistance to imatinib in vitro and in vivo.3,179 Development of resistance due to point mutation is not unexpected given the experience with imatinib in therapy of CML and CML blast crisis. We hypothesized that selective small-molecule inhibitors of PDGFRα that have a different chemical structure than imatinib might be able to overcome resistance to imatinib in this context. We have demonstrated that an alternative PDGFRα inhibitor, PKC412, is an effective inhibitor of the imatinib-resistant FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I mutant both in vitro and in vivo.179 These observations provide proof of principle that one strategy to preclude or overcome resistance mutations may be to use combinations of selective tyrosine kinase inhibitors that do not have overlapping toxicities.

The basis for the apparent lineage predilection of FIP1L1-PDGFRα for eosinophils is not well understood. No data have been reported regarding expression of FIP1L1 in eosinophils from healthy individuals. The FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion has been detected in enriched eosinophils, neutrophils, and mononuclear cells by FISH and reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in a patient with a diagnosis of systemic mast cell disease and eosinophilia, consistent with acquisition of the rearrangement in an early hematopoietic progenitor.176 It is possible that it is present in all myeloid lineages but that eosinophils are particularly sensitive to the FIP1L1-PDGFRα proliferative signal. Data that would support this include neutrophilia observed in many HES patients and elevated tryptase indicative of mast cell involvement.175 It will also be important to evaluate lymphoid lineage involvement of FIP1L1-PDGFRA, especially in those patients with T-cell clonality associated with HES. Each of these questions can be addressed with the molecular tools now in hand.

The presence of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene as a consequence of deletion can be used both to predict response to imatinib and to monitor response to therapy. We have developed sensitive RT-PCR–based assays for this purpose as well as FISH probes to reliably detect the deletion (Figure 2B-C). In a recent report, molecular remission was documented by PCR testing of the peripheral blood in 5 of 6 patients diagnosed with HES-MPD after 1 to 12 months of 400 mg imatinib daily.

Implications of FIP1L1-PDGFRA for the diagnosis, classification, and treatment of eosinophilic disorders

Diagnosis and classification

In the WHO classification, eosinophil clonality or the presence of another clonal marker distinguishes CEL from HES.10 However, the report by Cools et al3 indicates that FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusions can be identified in both HES and CEL patients, in contradistinction to their WHO classification as separate disorders.10 In light of these findings, a reappraisal of the WHO scheme for these eosinophilic diseases may ultimately be warranted. Given the early state of knowledge about FIP1L1-PDGFRA, any attempt at classification at this time would be considered preliminary, because additional data on prevalence, clinicopathologic correlates, and genetics will be important. However, based on available information, a tentative schema can be considered to help with clinical decision making and to provide a platform for addressing critical questions regarding classification.

It may be useful to consider the implications of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion within a recently proposed framework that classifies blood eosinophilia as reactive, clonal, and HES.15 One possible approach for evaluating hypereosinophilia in the context of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA discovery is presented in Figure 4. In patients whose workup is negative for secondary causes of eosinophilia, screening for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion could subsequently be undertaken using either RT-PCR or interphase/metaphase FISH. Patients positive for the fusion (and with fewer than 20% marrow blasts) could be classified into one clonal category of blood eosinophilia, “FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive chronic eosinophilic leukemia” (F-P+ CEL, Figure 4A). Similar to cases of BCR-ABL–positive CML, F-P+ CEL patients would be predicted to have a high hematologic response rate to imatinib. Based on the limited number of patients evaluated, this group currently accounts for 50% to 60% of all HES/CEL cases. However, a more accurate estimate of the proportion of F-P+ CEL patients will require screening larger numbers of individuals with idiopathic hypereosinophilia. The recent description of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion in 3 patients with a diagnosis of SM and eosinophilia indicates that the fusion may occur in a spectrum of clonal bone marrow disorders associated with eosinophilia and may not strictly define a subset of chronic eosinophilic leukemias per se. New classifications will need to reconcile such genotype-phenotype variations among patients positive for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion.

Possible diagnostic and treatment algorithm for hypereosinophilia. (A) Patients whose workup is negative for secondary causes of eosinophilia subsequently undergo testing for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion. Patients positive for the fusion are classified as having one category of FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive (F-P+) clonal eosinophilia (eg, F-P+ chronic eosinophilic leukemia [CEL] or F-P+ systemic mastocytosis [SM] with eosinophilia). A negative test for the fusion would classify patients into 1 of 3 diagnostic groups based on additional laboratory criteria: CEL, unclassified; hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES); or T-cell–associated HES. (B) A trial of imatinib is recommended for FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive CEL or SM patients. Conventional therapy or a trial of imatinib could be attempted for symptomatic FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients. FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients who demonstrate hematologic remissions with imatinib could be placed in a provisional category of imatinib-responsive (IR), warranting investigation of potential alternative targets of imatinib in these cases.

Possible diagnostic and treatment algorithm for hypereosinophilia. (A) Patients whose workup is negative for secondary causes of eosinophilia subsequently undergo testing for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion. Patients positive for the fusion are classified as having one category of FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive (F-P+) clonal eosinophilia (eg, F-P+ chronic eosinophilic leukemia [CEL] or F-P+ systemic mastocytosis [SM] with eosinophilia). A negative test for the fusion would classify patients into 1 of 3 diagnostic groups based on additional laboratory criteria: CEL, unclassified; hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES); or T-cell–associated HES. (B) A trial of imatinib is recommended for FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive CEL or SM patients. Conventional therapy or a trial of imatinib could be attempted for symptomatic FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients. FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients who demonstrate hematologic remissions with imatinib could be placed in a provisional category of imatinib-responsive (IR), warranting investigation of potential alternative targets of imatinib in these cases.

Patients without reactive eosinophilia and a negative screen for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion could be potentially categorized into 1 of at least 3 diagnostic groups (Figure 4A). FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients with a clonal cytogenetic abnormality, clonal eosinophils, or increased marrow blasts (5%-19%) could be categorized as “CEL, unclassified.” FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients without any of these clonal features or without increased marrow blasts could be assigned to the diagnostic group “HES.” A third group, designated “T-cell–associated HES,” would consist of HES patients in whom an abnormal T-cell population is demonstrated. Such diagnostic groups may not be mutually exclusive in all cases. Instances may arise in which CEL patients with the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion have another clonal marker and/or an abnormal population of T cells. For example, 2 patients in the study by Cools et al exhibited both the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion and clonal cytogenetic abnormalities.3 It is also possible that some patients with T-cell–mediated HES could have a FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion involving both the myeloid and lymphoid lineage. It will be of particular interest to analyze those patients with T-cell–mediated HES that progress to T-cell lymphoma or Sézary syndrome.

Treatment

The in vitro and in vivo data reported by Cools et al support the use of imatinib in FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive patients.3 Four of 9 patients exhibiting complete hematologic responses to imatinib had no detectable FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion.3 Therefore, in addition to conventional therapy, a trial of imatinib could have therapeutic value in some of these symptomatic FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients (eg, CEL, unclassified; or HES). The efficacy of imatinib in a cytokine-driven disease such as T-cell–associated HES has not yet been reported and requires investigation.

From a broader research perspective, it could also be useful to provisionally categorize FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients with hematologic responses to imatinib as “imatinib-responsive” (IR) (Figure 4B). Imatinib responsiveness in these patients may be indicative of clonal molecular abnormalities besides FIP1L1-PDGFRA. In such cases, an effort should be made to identify alternate targets of imatinib that contribute to the pathogenesis of these diseases.

Conclusion

Imatinib's efficacy in patients with HES and CEL has led to the identification of FIP1L1-PDGFRα as a pathogenetically relevant tyrosine kinase. These findings serve as a platform for new avenues of research that may translate into improved biologic and clinical characterization of these eosinophilic diseases. Future investigations should attempt to address the molecular basis for the response to imatinib in FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients and how the constitutively activated FIP1L1-PDGFRα kinase contributes to the phenotype of hypereosinophilia, similar to oncogenic fusions involving PDGFRβ in a subset of chronic MPDs. It will also be of interest to evaluate how the expression and function of the fusion differ between eosinophils and other cell lineages. One means of addressing this latter question is to study imatinib's effects on the proliferation, differentiation, survival, and intracellular signaling of eosinophils or other enriched myeloid or lymphocyte populations derived from patients with the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion.

Studies are ongoing to further characterize hematologic and clinical responses among FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive patients and the extent to which imatinib can elicit molecular remissions and cytogenetic responses in individuals with abnormal karyotypes. Similar to CML, it will be important to evaluate the maximally effective doses of imatinib needed to achieve these end points because suboptimal dosing may adversely impact response rates and the patterns of resistance that emerge.

In their 1994 Blood review, Weller and Bubley indicated that the goal of therapy for HES patients, particularly those with apparent chronic nonmalignant disease, should be control of organ damage rather than simple suppression of asymptomatic eosinophilia.21 This prevailing paradigm will require reappraisal in the subset of HES patients with FIP1L1-PDGFRA. It will be of great interest to ascertain whether early treatment of fusion-positive patients with asymptomatic hypereosinophilia can forestall the development of organ disease and increase disease-free and overall survival. Screening of archival specimens for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion will allow comparison of the natural history of HES in conventionally treated patients with those enrolled in future studies evaluating the efficacy of imatinib. These new biologic and clinical data will provide a useful framework that clinicians, pathologists, and molecular biologists can use to develop improved classification guidelines and algorithms for the diagnosis and treatment of these eosinophilic disorders.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 20, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1824.

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (K23HL04409 [J.G] and CA66996 [D.G.G.]) and by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (D.G.G.). J.C. is a “postdoctoraal onderzoeker” of the “F.W.O.-Vlaanderen.”

We thank Dr Iwona Wlodarska, Center for Human Genetics, Leuven, Belgium, for kindly providing the FISH image in Figure 2. We also gratefully acknowledge collaborating physicians and investigators for their participation in the clinical and biologic characterization of patients, Kathleen Dugan and Lenn Fechter for their assistance in patient care, Rhoda Falkow for tissue banking of clinical specimens, and patients for their participation in studies of imatinib in HES. J.G. also recognizes Dr Peter Greenberg for his valuable mentorship on the NIH K23HL04409 grant.

![Figure 4. Possible diagnostic and treatment algorithm for hypereosinophilia. (A) Patients whose workup is negative for secondary causes of eosinophilia subsequently undergo testing for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion. Patients positive for the fusion are classified as having one category of FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive (F-P+) clonal eosinophilia (eg, F-P+ chronic eosinophilic leukemia [CEL] or F-P+ systemic mastocytosis [SM] with eosinophilia). A negative test for the fusion would classify patients into 1 of 3 diagnostic groups based on additional laboratory criteria: CEL, unclassified; hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES); or T-cell–associated HES. (B) A trial of imatinib is recommended for FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive CEL or SM patients. Conventional therapy or a trial of imatinib could be attempted for symptomatic FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients. FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients who demonstrate hematologic remissions with imatinib could be placed in a provisional category of imatinib-responsive (IR), warranting investigation of potential alternative targets of imatinib in these cases.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/8/10.1182_blood-2003-06-1824/6/m_zh80080459730004.jpeg?Expires=1768806142&Signature=47ZYkQEyVrdNFjAd4D7bn8TdDcDnLhfAOzxWI1RqIXyoIXIhfg9Kx3sgMPmoL70RHDQp1HEOdavLfFAhpLnhXZExlH~sbsmav4AYP42bMBlz9XkfZVzjafF7J4UpC-y6sMVQldZfmHyxTe2Hu-gv6hxxFi1PquVrNpfR9AOgTaxaWC6E9dJSEiEYlVasGPF4evNcxH3WglndaSahIdmvJr7uhjQQQGCkB2qGRA2y1gVX4APsstJuOk~dFTMvrgiTD8T3dKPWiP6ydsvfcF4sB-r~YjwJM5HcaQoOuGmQw7ylPk7H~AWCjTbV05477wiCak~J8RKAwxxami2o44K0Wg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Possible diagnostic and treatment algorithm for hypereosinophilia. (A) Patients whose workup is negative for secondary causes of eosinophilia subsequently undergo testing for the FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion. Patients positive for the fusion are classified as having one category of FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive (F-P+) clonal eosinophilia (eg, F-P+ chronic eosinophilic leukemia [CEL] or F-P+ systemic mastocytosis [SM] with eosinophilia). A negative test for the fusion would classify patients into 1 of 3 diagnostic groups based on additional laboratory criteria: CEL, unclassified; hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES); or T-cell–associated HES. (B) A trial of imatinib is recommended for FIP1L1-PDGFRA–positive CEL or SM patients. Conventional therapy or a trial of imatinib could be attempted for symptomatic FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients. FIP1L1-PDGFRA–negative patients who demonstrate hematologic remissions with imatinib could be placed in a provisional category of imatinib-responsive (IR), warranting investigation of potential alternative targets of imatinib in these cases.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/8/10.1182_blood-2003-06-1824/6/m_zh80080459730004.jpeg?Expires=1768806143&Signature=sPw4TFST~ewoxt2psHZHVPk44jU5fLzzFjqz8XpZ1h0V7MR9MP1Es9qZHqUEJjXji0ozs3VOp40mropq4sASiHz66HeK~8NPIyovZZlIWBv6YfquylfGLKycvsII0DZpG8OJkpDYhToEFFMy4Dj4lURtjHE25Q7E1yfDW5duD6lSK4vky5MWxkg8njEnrldcpTl3qpgUbOZrFsxKq6vH-aGaV0mDZFxwJkt1Dy~QMBtQY9eMOpMG8ipbgMOMasJJGxWFd8WE28DeCmV2MTH8UKLL~4pj2kWRGl5OqcGOKURDcTGugDx4Gj1z9bpeO1zRRchVMgBqb9swO52NFHiyjQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)