Abstract

GATA-1 is the founding member of a transcription factor family that regulates growth and maturation of a diverse set of tissues. GATA-1 is expressed primarily in hematopoietic cells and is essential for proper development of erythroid cells, megakaryocytes, eosinophils, and mast cells. Although loss of GATA-1 leads to differentiation arrest and apoptosis of erythroid progenitors, absence of GATA-1 promotes accumulation of immature megakaryocytes. Recently, we and others have reported that mutagenesis of GATA1 is an early event in Down syndrome (DS) leukemogenesis. Acquired mutations in GATA1 were detected in the vast majority of patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (DS-AMKL) and in nearly every patient with transient myeloproliferative disorder (TMD), a “preleukemia” that may be present in as many as 10% of infants with DS. Although the precise pathway by which mutagenesis of GATA1 contributes to leukemia is unknown, these findings confirm that GATA1 plays an important role in both normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Future studies to define the mechanism that results in the high frequency of GATA1 mutations in DS and the role of altered GATA1 in TMD and DS-AMKL will shed light on the multistep pathway in human leukemia and may lead to an increased understanding of why children with DS are markedly predisposed to leukemia.

Introduction

The incidence of leukemia in children with Down syndrome (DS) is 1 in 100 to 200, which is 10- to 20-fold higher than in children without DS. Although in non-DS children lymphoid neoplasms comprise most of the leukemias arising in this age group, half of the leukemias in DS are myeloid. Children with DS exhibit a 46-fold excess incidence of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) accounting for at least 50% of these cases.1 In addition to acute leukemia, children with DS are also predisposed to developing the related transient myeloproliferative disorder (TMD). At least 10% of infants with DS develop TMD, a disease in which immature megakaryoblasts accumulate in liver, bone marrow, and peripheral blood; this disorder undergoes spontaneous remission in most cases.2-4 Of note, approximately 30% of DS infants with TMD develop AMKL within 3 years.1

TMD blasts are morphologically indistinguishable from AMKL blasts, contributing to the hypothesis that the second disease is derived from the first.5,6 Often the karyotype of the AMKL blasts is more complex than that of the TMD, but contains abnormalities observed in the original TMD clone, consistent with clonal evolution.7-11 Classified as FAB M7 subtype, these blasts exhibit classical α-naphthyl acetate esterase activity with a multifocal punctate cytoplasmic staining pattern that is only partially inhibited by sodium fluoride.12 Immunophenotyping shows that the blasts express the myeloid markers CD33 and CD13, in addition to at least one platelet-associated antigen (CD36, CD41a, CD41b, or CD61). A proportion of these blasts also express erythroid-specific mRNAs, such as γ-globin and erythroid δ-aminolevulinate synthase.13 Taken together, these observations are consistent with the theory that TMD and AMKL arise from an immature megakaryocytic or a common erythroid megakaryocytic precursor.13

The role of chromosome 21 in DS leukemia

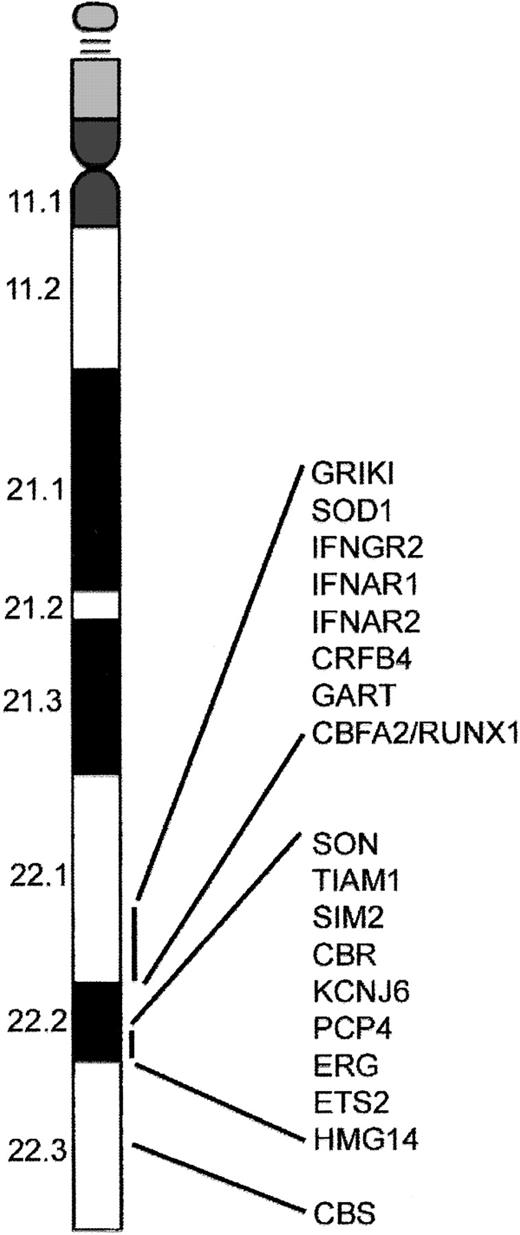

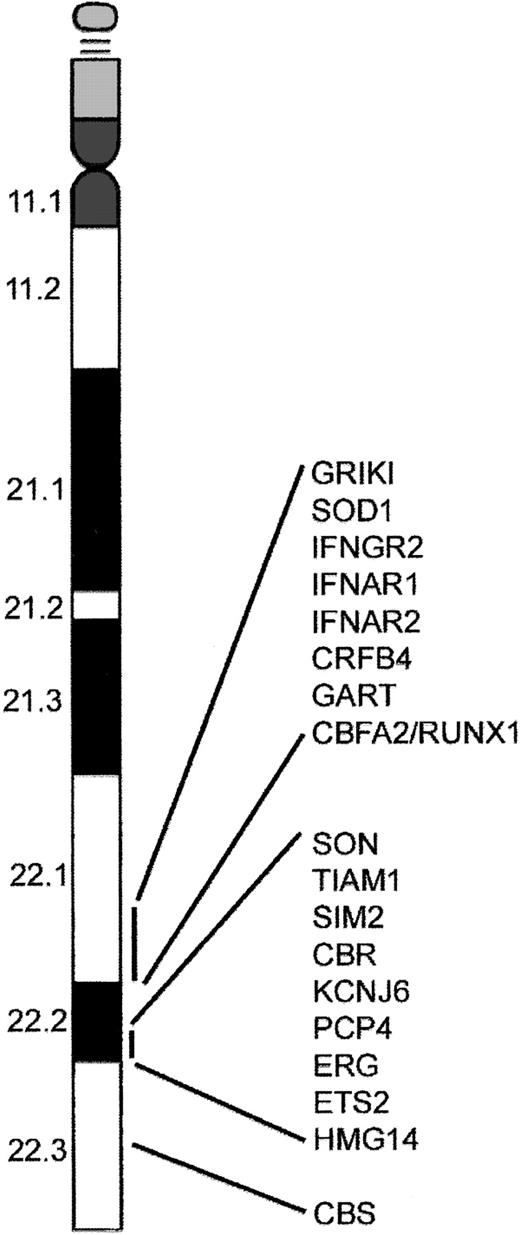

Several models have been proposed to explain the increased incidence of AMKL and TMD in DS. These include gene dosage, mutations of genes on chromosome 21, genetic imprinting leading to homozygosity, and altered folate metabolism. The most popular of these is increased gene dosage of a leukemia predisposition gene or hematopoiesis regulatory gene residing on chromosome 21.14-17 This model is supported by the observation that acquisition of one or more additional chromosome 21 homologs is a common numerical abnormality in acute leukemia.18-20 Even though there appears to be no direct correlation between the biologic features of AMKL and TMD and known function of genes identified on chromosome 21, it is likely that one or more of these genes are involved. Alternatively, overexpression of a gene present on chromosome 21 may alter expression of genes on other chromosomes that subsequently affect hematopoiesis. For example, the gene encoding cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), located on human 21q22.3 (Figure 1), is expressed at a level nearly 12.5-fold greater in a DS AMKL cell line compared to a similar non-DS AMKL cell line.21 The increased activity of CBS in DS results in significantly lower plasma homocysteine, methionine, S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet), and S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoHyc) levels in DS individuals compared with a non-DS control group.22 Alterations in AdoMet and AdoHyc levels may result in altered methylation of CpG islands, thereby affecting gene expression. In addition, low homocysteine levels perturb folate metabolism by trapping 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate resulting in a “functional” folate deficiency. This may result in increased rates of DNA mutation,23 predisposing these children to leukemia.24 Interestingly, it may be that the greater sensitivity to chemotherapy shown by patients with DS-AMKL results from the overexpression of CBS.21

A subset of genes located on chromosome 21. The distal region of chromosome 21 present in 3 copies in cells from children with DS contains several putative leukemogenic genes including RUNX1. In addition, the region 21q22.3 contains the gene that encodes the enzyme cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), which is involved in the metabolism of cytosine arabinoside and may be responsible for increased sensitivity of DS AMKL blasts to this compound.91

A subset of genes located on chromosome 21. The distal region of chromosome 21 present in 3 copies in cells from children with DS contains several putative leukemogenic genes including RUNX1. In addition, the region 21q22.3 contains the gene that encodes the enzyme cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), which is involved in the metabolism of cytosine arabinoside and may be responsible for increased sensitivity of DS AMKL blasts to this compound.91

Perhaps the most interesting candidate leukemia-predisposing gene on chromosome 21 is RUNX1(AML1). The transcription factor RUNX1 is required for generation of all definitive hematopoietic lineages.25 RUNX1 gene rearrangements are involved in some of the recurring translocations associated with leukemia; these include t(8;21) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML M2), t(3;21) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in blast crisis, and t(12;21) in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).26-28 Mutations in the DNA-binding Runt domain of RUNX1 result in a familial platelet disorder with predisposition to AML,29,30 and are present in about 10% of sporadic cases of de novo AML31,32 and in myeloid malignancies with acquired trisomy 21.32 Mutations in the RUNX1 Runt domain were not detected in samples from individuals with DS-AMKL, arguing that RUNX1 mutations are not involved in the etiology of AMKL.32-34 However, this finding does not exclude a pathogenic role for increased gene dosage of RUNX1 in the development of AMKL. Other putative leukemic oncogenes on chromosome 21 include the interferon α/β receptor (IFNAR), cytokine family 2-4 (CFR 2-4), phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase (GART), and the gene with significant homology to MYC and MOS (SON).4 Several of the interesting genes that reside on chromosome 21 in the DS critical region are depicted in Figure 1.

Another model for why DS children are predisposed to leukemia is based on genetic mapping studies that suggest an increased frequency of disomic homozygosity in DS individuals with TMD and AMKL.35 Nondisjunction of chromosome 21 may result in disomic homozygosity of mutated tumor suppressor genes.36 For this hypothesis to be true, it is essential that the DS child inherit 2 copies of the same chromosome with a mutated allele. This is possible in the 25% of DS cases where the disjunction occurs at meiosis II. To date, some evidence suggests that in DS-AMKL and TMDs there is a high prevalence of meiosis II errors and increased disomic homozygosity in the pericentromeric region encompassing the most proximal 10% of 21q.14,35-37 However, there is very little evidence to support the silencing of the normal allele on the third chromosome 21 by genetic imprinting. This model also requires the unlikely possibility of a mutated tumor suppressor gene to be present in the general population at high frequency.

The involvement of chromosome 21 in DS leukemogenesis might be more complex than simple gene dosage or disomic homozygosity of a mutated allele. Molecular deletions in the long arm of one chromosome 21 homolog have been reported in leukemic cells from 5 acute leukemia patients (4 AMKL, 1 ALL). Subsequently, cryptic deletions and complex rearrangements involving the same chromosome 21 segments have been reported in a non-DS infant with TMD (with acquired trisomy 2138 ). Interestingly, segments involved in these deletions included the RUNX1 locus 21q22.1-22.2 in the ALL and 3 of 4 AMKL patients.39 A final hypothesis is that, in addition to a role for genes located on chromosome 21, factors responsible for nondisjunction of chromosome 21 in DS may predispose to a state of chromosomal instability. A significant increase in polymorphisms of the enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) has been shown in mothers of individuals with DS.23 These polymorphisms lead to reduced enzyme activity and altered folate metabolism and cellular methylation reactions.40 This is of interest because a recent study demonstrated folate supplementation in pregnant mothers conferred protection from ALL in childhood.41

Regardless of the mechanism, trisomy 21 certainly plays a role as a potent first hit in the leukemic process. TMD, characterized by abnormal proliferation of blasts and a unique association with DS, is often present at the time of birth or in the early neonatal period. This observation, coupled with the fact that acute leukemias in DS occur relatively early, with the highest risk at ages younger than 4 years, suggests that either the secondary mutations needed to fuel abnormal myelopoiesis and acute leukemia are few in number, or that trisomy 21 predisposes to a state of genetic instability resulting in rapid acquisition of other mutations.

GATA-1 in normal and abnormal hematopoiesis

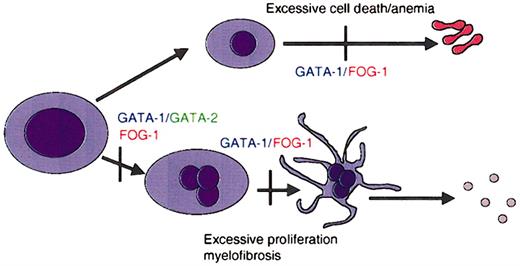

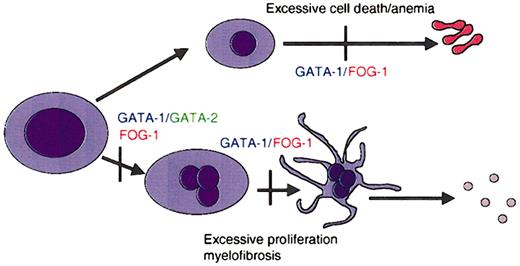

The development of blood cells of various lineages from hematopoietic stem cells is controlled by cell-restricted transcription factors (for a review, see Cantor and Orkin42 ). Among these, several members of the GATA family play key roles in specification and maturation of a subset of hematopoietic lineages. For example, GATA-1 is essential for the maturation of erythroid cells and megakaryocytes (Figure 2).42 GATA-2 participates in the maintenance and proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells as well as in the specification of mast cells.43 GATA-2 can also substitute for absence of GATA-1 in early megakaryocyte specification.44 GATA-3, on the other hand, is required for T-cell development and regulating the decision between Th1 and Th2 cell development.45-47

GATA factors in hematopoiesis. Schematic representation of the requirements for GATA-1 and its cofactor FOG-1 during lineage specification and maturation of erythroid cells and megakaryocytes. Vertical bars represent maturation arrest observed in the absence of GATA-1 or FOG-1, as determined by murine gene targeting experiments. GATA-1 is required for differentiation of megakaryocytes and erythrocytes, as well as for mast cells and eosinophils.

GATA factors in hematopoiesis. Schematic representation of the requirements for GATA-1 and its cofactor FOG-1 during lineage specification and maturation of erythroid cells and megakaryocytes. Vertical bars represent maturation arrest observed in the absence of GATA-1 or FOG-1, as determined by murine gene targeting experiments. GATA-1 is required for differentiation of megakaryocytes and erythrocytes, as well as for mast cells and eosinophils.

The most extensively characterized member of the GATA family of transcription factors, GATA-1, is an X chromosome– encoded gene that is expressed primarily in erythroid cells, megakaryocytes, mast cells, and eosinophils, cell types that express a large number of genes that harbor GATA DNA-binding motifs. GATA-1 has 3 well-studied functional domains: an N-terminal transactivation domain and 2 zinc fingers. The C-terminal zinc finger is required for binding of GATA-1 to DNA, whereas the N-terminal zinc finger stabilizes binding to a subset of sites, termed palindromic motifs.48 In addition to binding DNA, the N-finger plays an important role by recruiting a cofactor named friend of GATA-1 (FOG-149 ). Both zinc fingers of GATA-1 are essential for normal activity, but the role of the N-terminal activation domain is less clear. This region was initially defined in transient reporter assays in fibroblasts.50 Results of several studies, however, have suggested this domain is not required for GATA-1 function. First, GATA-1 molecules that lack the N-terminal activation domain rescued the differentiation of a GATA-1–deficient erythroid cell line.51 Second, the activation domain was dispensable in the conversion of an early myeloid cell line, 416B, to megakaryocytes.52 Finally, mice engineered to express only a variant of GATA-1 that lacks the N-terminal transactivation domain were born and appeared healthy.53 We will return to the question of whether this activation domain plays an essential role in hematopoiesis.

Various lines of mice with an alteration in Gata1 have been developed (Table 1 presents a complete list and details of Gata1-altered mice). Initial studies with mice that lack GATA-1 expression in all cells (GATA-1 null mice) revealed that GATA-1 is essential for the proper development of erythroid cells.54 GATA-1 null mice die of anemia at embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5). Subsequently, 3 other gene-targeted mouse strains relevant for this review have been generated that harbor deletions within the cis-regulatory elements that regulate GATA-1. In GATA-1.05 mice, deletion of sequences in the promoter of GATA-1 reduce GATA-1 expression to 5% of normal in all cells.55 This is sufficient to block erythropoiesis, and as a consequence, both female homozygous mutant mice and male hemizygous mutant mice die in utero at E12.5. Female heterozygous mice survive but develop a myelodysplastic syndrome and die prematurely at about 5 months of age.55 In the other 2 strains of mice, sequences containing an enhancer located 3.4 kb upstream of the GATA-1 were deleted (GATA-1 knock-down and GATA-1low mice).56,57 In these 2 strains of mice GATA-1 is virtually absent from megakaryocytes. Studies with these mice have shown that GATA-1 is required for the proper maturation of megakaryocytes. In the absence of GATA-1, megakaryocytes proliferate excessively and fail to generate platelets.56,58 Furthermore, abnormal megakaryocytes accumulate in the spleen and bone marrow of these GATA-1–deficient mice, resulting in anemia and thrombocytopenia.56 Analysis of the GATA-1low mice shows they develop extramedullary hematopoiesis in the liver and myelofibrosis of the bone marrow and mice have been proposed as a model for human myelofibrosis.59,60 Finally, more recent studies with Gata1 gene–targeted mice have also revealed an essential role for GATA-1 in the development of 2 other hematopoietic lineages: eosinophils61,62 and mast cells.63

The existence of mice that express reduced levels of GATA-1 has facilitated a more detailed structure-function study of GATA-1 domains in vivo.53 Mice harboring wild-type and mutant GATA-1 transgenes were bred to the GATA-1.05 mutant mice. Although the male GATA-1.05 mutant mice die in midgestation of anemia, GATA-1.05 mice that harbored a wild-type GATA-1 transgene were born at the expected frequency and were healthy. As expected, GATA-1 transgenes that lacked either zinc finger failed to rescue the embryonic lethality of GATA-1.05 mice. Surprisingly, however, mice that expressed a GATA-1 transgene without the N-terminal activation domain also survived, but only when the transgene was expressed at high levels.53 These findings suggest the N-terminal activation domain does have a critical function in blood cell development.

Obviously GATA-1 plays important roles in normal hematopoiesis, but do alterations in GATA-1 activity participate in human blood disorders? Earlier studies have shown this to be the case. Inherited mutations in the N-terminal zinc finger domain of GATA-1, which disrupt the interaction between GATA-1 and FOG-1, cause congenital dyserythropoietic anemia and thrombocytopenia.64-66 Also, mutations in GATA-1 that interfere with normal DNA binding by the N-finger of GATA-1 have been associated with dyserythropoiesis and thrombocytopenia in humans.67 Similarly, mice that harbor one of the mutations in GATA-1 seen in human patients that disrupts binding to FOG-1 (Val205Gly mutants) suffer from a phenotype (anemia and thrombocytopenia) that mimics the human disease (Table 1).44

Given that numerous missense mutations in GATA1 cause defective hematopoiesis, it seemed likely that distinct mutations in GATA1 might result in other hematopoietic diseases, including myelodysplastic syndromes and AMLs. Recently this has been borne out because a number of groups have shown mutations in GATA1 in one form of AML, the megakaryoblastic leukemia associated with DS.33,68-71 To date, GATA1 mutations have been detected in a total of 43 of 51 AMKL patients (Table 2). Importantly, mutations in GATA1 were not detected in leukemic cells of DS patients with other types of acute leukemia, or in other patients with AMKL who did not have DS.33 Furthermore, GATA1 mutations were not detected in DNA from other patients with other subtypes AML or healthy individuals. Finally, these studies demonstrated that these mutations were somatically acquired because remission samples did not harbor GATA1 mutations. Based on these observations, it appears that disruption of normal GATA-1 function is an important, if not essential, step in the pathogenesis of AMKL.

To determine if GATA1 mutations in the presence of trisomy 21 are an early event needed for the proliferative process common to both TMD and AMKL, or are involved in the transformation of “benign” TMD to the “malignant” AMKL, several groups have investigated whether GATA1 mutations were present in TMD patients. GATA1 was found to be mutated in 66 of 68 TMD patients examined (Table 2),68-72 suggesting that GATA1 mutagenesis is an early event in DS myeloid leukemogenesis that contributes to both TMD and AMKL.

Timing, frequency, and natural history of GATA1 mutations in DS

These described findings raise important questions about the timing, frequency, and natural history of GATA1 mutations in DS. The importance of determining when mutations arise is that if mutations occur during a restricted temporal window, for example, exclusively in fetal life, this would suggest that mutations only occur in a defined hematopoietic developmental context in trisomy 21 cells (see “TMD and AMKL in DS: a model for multiple hits in childhood leukemia”). Clearly, because TMD presents in the neonatal period, GATA1 mutations in this case almost certainly occur in utero.68-70,72 However, what of those cases of AMKL that are not preceded by TMD? In one informative case identical twins with an acquired trisomy 21 were shown to have precisely the same GATA1 mutations in leukemic cells leading the authors to speculate that a GATA1 mutation must have arisen in a hematopoietic progenitor with acquired trisomy 21 in one of the twins in fetal life and was then transferred to the other fetus via a shared embryonic circulation.70 More generally, the question has been recently addressed by analysis of neonatal blood spots of 4 patients with AMKL who did not have clinically overt antecedent TMD phase. GATA1 mutations were present at birth in 3 of 4 of these patients who went on to develop AMKL 12 to 26 months later.73 In the fourth patient failure to detect GATA1 mutation in neonatal blood spots (where there are on average 30 000 nucleated cells) may reflect the rarity of a clone containing a GATA1 mutation rather than its absence. These data would support the contention that most (if not all cases) GATA1 mutations arise in utero.

In an extension of this observation, GATA1 mutations were also detected in neonatal blood spots from 2 of 21 randomly selected otherwise normal DS neonates.73 Importantly, no GATA-1 mutations were detected in 62 non-DS cord blood samples. The presence of GATA1 mutations in 2 of 21 otherwise healthy DS neonates could suggest the presence of clinically silent megakaryoblast proliferation in these infants. Alternatively, acquisition of GATA1 mutation per se in a fetal trisomy 21 hematopoietic progenitor can give rise to clinically overt TMD only if the mutation occurs early enough in gestation to produce a large clone at birth.

The question of the frequency of GATA1 mutations in DS neonates and children is also unclear. Because GATA1 mutations can be clinically silent at birth, the overall frequency at which mutations occur is almost certainly higher frequency than that of TMD (about 10% of all DS neonates). Moreover, we have recently observed multiple independent GATA1 mutant clones in 4 of 12 DS AMKL patients,73 suggesting that GATA1 mutations are present at a remarkably high frequency in DS.

Nature of GATA1 mutations in DS leukemia

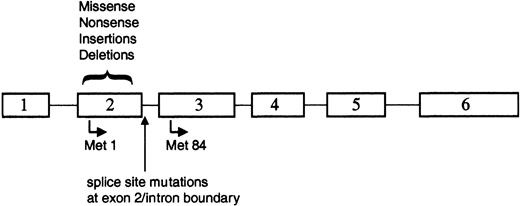

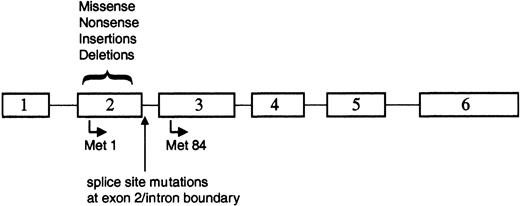

The majority of the reported GATA1 mutations involved small deletions or insertions in sequences encoding exon 2 of GATA1 (Figure 3; Table 2). Each of these alterations resulted in a disruption of the normal reading frame of GATA1 and an invariable introduction of a premature stop codon. As a consequence of these changes, full-length GATA-1 is not expressed in the leukemic cells. Surprisingly, however, a short isoform of GATA-1, previously described as GATA-1s,74 is expressed in both TMD and AMKL blasts33,71 (S.G. and J.D.C., unpublished observations, December 2002). GATA-1s is likely to arise by alternate translation from Met84, downstream of each of the patient mutations (Figure 3). GATA-1s lacks the N-terminal activation domain, but retains both zinc fingers and the entire C-terminus.50 GATA-1s binds DNA efficiently in vitro, dissociates from DNA at a rate similar to full-length GATA-1, and interacts with the FOG-1 cofactor to the same extent as wild-type GATA-1.33 However, due to the absence of the N-terminal activation domain, the shorter variant has reduced transactivation potential.33,53,74

GATA1 is mutated in TMD and AMKL. Positions of the various alterations in GATA1. All of the mutations are located within exon 2 or the proximal nucleotides of the downstream intron. Translation that initiates at Met1 produces the 50-kDa full-length protein, whereas use of the alternate initiation codon at Met84 generates a shorter 40-kDa isoform.

GATA1 is mutated in TMD and AMKL. Positions of the various alterations in GATA1. All of the mutations are located within exon 2 or the proximal nucleotides of the downstream intron. Translation that initiates at Met1 produces the 50-kDa full-length protein, whereas use of the alternate initiation codon at Met84 generates a shorter 40-kDa isoform.

Alternative splicing of the GATA-1 mRNA may provide another mechanism for production of the short isoform of GATA-1, because a subset of patients with TMD or AMKL harbored mutations in GATA1 that disrupt mRNA splicing70 (Figure 3). In analyzing the mRNA from leukemic cells of 3 patients who harbored exon 2 splice site mutations, Rainis and colleagues could only detect the presence of a shorter mRNA that lacked exon 2.70 In contrast, both the wild-type mRNA and the short mRNA lacking exon 2 were detected in leukemic samples without splice site mutations as well as in normal bone marrow. Together, these observations suggest that wild-type GATA1 produces 2 mRNAs, which may account for the production of the 2 protein isoforms, and that alternative splicing may provide the template for subsequent expression of the GATA-1s isoform in the majority of leukemic patients.

How do the mutations in GATA1 promote leukemia?

Calligaris et al initially proposed that GATA-1s is a normal isoform of GATA-1 because its expression was observed in a variety of human cell lines as well as in mouse fetal liver.74 Consistent with this, we have detected both full-length and GATA-1s in human CD34+ cells cultured to differentiate along the erythroid lineage (A. Muntean and J.D.C., unpublished observations, March 2003), as well as in a variety of human hematopoietic cell lines.33 What possible role could GATA-1s play during blood development? Because GATA-1s can bind DNA and interact with FOG-1, but exhibits a reduced transactivation potential, it may act as a dominant-negative protein. During normal hematopoiesis, when both GATA-1 and GATA-1s are translated, GATA-1s may down-modulate GATA-1 function. In DS-AMKL blasts, however, only the GATA-1s isoform is produced (because GATA1 is encoded on the X chromosome in leukemic blasts only the mutant allele is active and exclusively produces GATA-1s33 ). Hence, during leukemogenesis GATA-1s may act by repressing the activity of a related GATA protein, possibly GATA-2. GATA-2 is expressed in hematopoietic progenitors and can substitute for GATA-1 during early megakaryocyte specification.44 There is at least one other example in which frame shift mutations in a transcription factor result in production of a dominant-negative isoform: mutations in the CEBPA gene have been identified in a subset of AMLs.75 Similar to GATA1 mutations, mutations in CEBPA result in the introduction of premature stop codons that block expression of full-length protein, but allow expression of a protein that is initiated downstream of the stop codon. These shortened isoforms act as dominant-negative proteins that interfere with the normal function of full-length C/EBP-α and promote malignancy in the heterozygous state.

Although previous studies have suggested that the N-terminal activation domain of GATA-1 is dispensable, none of these studies specifically addressed the requirement for the N-terminus in megakaryocyte growth. As such, there may be an essential function for the N-terminus in megakaryocytes. Consistent with this hypothesis, a recent report has shown that GATA-1 physically interacts with RUNX1 during megakaryocytic differentiation. In this study, both the N-terminus (amino acids 1-85) and the C-terminus of GATA-1 (amino acids 319-413) were necessary for the interaction.76 Thus, the short isoform, which is deficient for binding RUNX1, may have an altered activity in leukemic blasts that could contribute to the abnormal growth of megakaryoblasts.

Surprisingly, however, recent studies have demonstrated that expression of high levels of GATA-1s can compensate in vivo for the absence of full-length GATA-1 in erythroid cells of GATA-1 1.05 mice.53 These rescued mice, which express GATA-1s in the absence of full-length GATA-1, do not exhibit any hematologic deficiencies, indicating that the shortened form of GATA-1 can substitute for full-length GATA-1, when substantially overexpressed. Thus, although we cannot discriminate between a quantitative or qualitative deficiency of GATA1 in DS malignancies, the finding of Shimizu et al53 favors the model that, although the leukemic cells produce GATA-1s, the levels are insufficient to promote proper development. The fact that every single GATA1 mutation identified to date is predicted to abolish expression of full-length GATA-1, while allowing for expression of GATA-1s, strongly argues that expression of this short isoform is a key component of leukemogenesis. Perhaps instead of playing an oncogenic role, the short isoform may alternatively be required for survival of mutant megakaryoblasts.70 Interestingly, Xu et al recently demonstrated that expression of the full-length GATA-1, but not the GATA-1s, can to some extent, rescue differentiation in an AMKL-derived cell line.71

GATA1mutations establish the clonal nature of TMD and AMKL blasts

It has been suggested previously that TMD and AMKL form 2 ends of an evolving malignant process, and that AMKL arises from the initial TMD clone after acquiring additional abnormalities.12,77-80 In a recent study on the incidence of GATA1 mutations in TMD and AMKL, TMD resolved spontaneously in a majority of the patients. Eighteen percent of patients (3 of 17), however, developed AMKL with a median follow-up of 30 months. Identical GATA1 mutations were present in both the TMD and AMKL blasts from 2 of these patients for whom sequential samples were available.70 The presence of an identical GATA1 mutation has also been reported by Hitzler and colleagues, in a patient for whom samples were available from TMD and AMKL.68 In all of these cases, samples from the same patients during clinical remission did not have GATA1 mutations.

TMD and AMKL in DS: a model for multiple hits in childhood leukemia

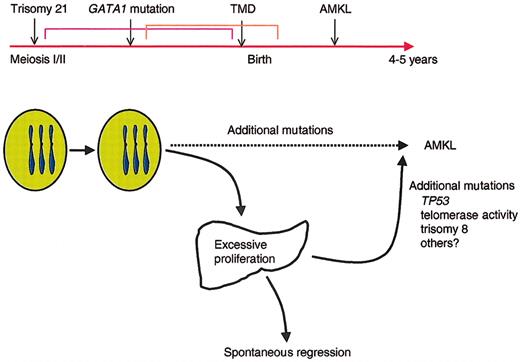

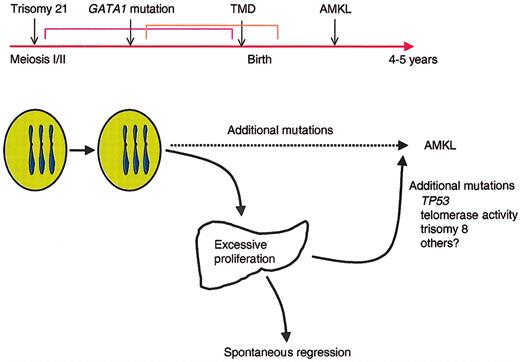

Although all DS children have trisomy 21, only 10% develop TMD, and even fewer, less than 1%, develop acute leukemia. These observations support the model that DS leukemogenesis is a multistep process in which progenitor cells acquire multiple genetic lesions during the progression to acute leukemia (Figure 4). Trisomy 21 is the first event but is not sufficient for the expansion of megakaryoblasts seen in TMD. The recent discovery that mutations in GATA1 occur in nearly every individual with either TMD or AMKL33,68,70,72 suggests that disruption of wild-type GATA-1 activity is an essential second step in the development of leukemia in DS. We hypothesize that mutagenesis of GATA1, in conjunction with trisomy 21, is sufficient to promote the transient expansion of immature megakaryoblasts seen in TMD and that additional mutations are involved in the transformation to acute leukemia. This model of multiple hits is consistent with accumulating evidence suggesting that at least 2 cooperating mutations, one that promotes enhanced proliferation and a second that disrupts differentiation, are necessary for the development of AML.81 Regardless of the mechanism of production or action of GATA-1s, it is likely that the GATA1 mutations contribute to leukemia by providing a block in megakaryocytic differentiation. GATA1 mutations in megakaryoblastic leukemia may act in a manner analogous to those in CEPBA in AML, whereas the increased dosage of genes on chromosome 21 likely impart a survival advantage to progenitors, in a manner similar to the activating mutations in FLT3 found in other AMLs.82

Model for the progression of TMD and AMKL in DS. Trisomy 21 likely represents the initiating event in leukemogenesis of DS because it occurs very early in embryogenesis. The subsequent mutagenesis of GATA1 and selection of progenitor cells that harbor GATA1 mutations may be the second initiating event that leads to the neonatal appearance of TMD in at least 10% of infants with DS. In the majority of infants with TMD, the GATA1 mutant clones disappear during remission, but 30% of the time, the mutant clones acquire additional mutations that promote the development of acute leukemia by the age of 4 years.

Model for the progression of TMD and AMKL in DS. Trisomy 21 likely represents the initiating event in leukemogenesis of DS because it occurs very early in embryogenesis. The subsequent mutagenesis of GATA1 and selection of progenitor cells that harbor GATA1 mutations may be the second initiating event that leads to the neonatal appearance of TMD in at least 10% of infants with DS. In the majority of infants with TMD, the GATA1 mutant clones disappear during remission, but 30% of the time, the mutant clones acquire additional mutations that promote the development of acute leukemia by the age of 4 years.

Even though the presence of trisomy 21 and GATA1 mutations appears to be adequate for the excessive proliferation of megakaryoblasts seen in TMD, it appears to be insufficient for leukemogenesis because the majority of TMDs resolve spontaneously. The spontaneous disappearance of these immature cells shortly after birth suggests that a specific environment might be essential for the proliferation of these cells. An attractive hypothesis to explain this has been the suggestion that TMD arises in the fetal liver (for a review, see Gamis and Hilden4 ). The spontaneous regression of TMD shortly after birth could then be explained by the loss of a permissive fetal hematopoietic environment. Interestingly, oncostatin M, which cooperates with glucocorticoids to induce hepatic differentiation and termination of fetal liver hematopoiesis,83,84 is also an inducer of myeloid differentiation in vitro.85

Based on the data now available from the recent studies on TMD and AMKL in DS, we propose a model of leukemogenesis in which trisomy 21 cooperates with a nonfunctional/dysfunctional GATA-1 transcription factor to specifically target a megakaryocytic or common erythroid-megakaryocytic precursors resulting in excessive proliferation. These cells are not frankly leukemic and likely need a specific milieu to proliferate (eg, fetal liver). However, these excessively proliferating immature cells are prone to acquire additional lesions, which, in turn, result in overt leukemia. These additional lesions could be mutations in p53,86 altered telomerase activity,87 or additional acquired karyotypic abnormalities, trisomy 8 being the most common in DS-AMKL.70,88,89 Additional studies investigating mutations in genes commonly involved in AML, such as FLT3 and KRAS1/NRAS,90 in sequential samples from TMD and AMKL patients are warranted and will provide important insights into the mechanism of leukemogenesis in DS as well as possible tools for identifying TMD patients at a high risk of developing AMKL.

Summary

Although GATA1 normally promotes the development of megakaryocytes, erythroid cells, mast cells, and eosinophils, mutagenesis of GATA1 is an early event in megakaryoblastic leukemia. In retrospect, perhaps, the observation that mutations in GATA1 interfere with the normal development of megakaryocytes is not surprising; however, what is very surprising is that these mutations are only found in those individuals with DS. Even more intriguing is the finding that these mutations have been identified in nearly every patient, and both in TMD and AMKL. Despite this recent advance, many questions regarding leukemia in children with DS remain unresolved: What are the factors contributed by chromosome 21? What is the mechanism of mutagenesis of GATA1? Why is GATA1 targeted to such a high degree exclusively in children with DS? Future studies will address these important questions and shed light on the mysterious predisposition of individuals with DS to leukemia.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 25, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1556.

Supported in part by a Junior Faculty Award from the American Society of Hematology (J.D.C.) and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute).

The authors thank Drs Michelle Le Beau and Mitchell Weiss for their helpful comments.