Visual Abstract

TO THE EDITOR:

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) represent hematological disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis and increased risk of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1

MDS with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS)2 is associated with a lower risk of progression to AML and often characterized by red blood cell transfusion–dependent anemia. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents are the first-line treatment; however, their effectiveness is limited.3

Luspatercept, a recombinant fusion protein neutralizing specific transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) ligands, is approved for treating patients with red blood cell transfusion–dependent anemia and MDS-RS after erythropoiesis-stimulating agent failure.4 However, its clinical efficacy is restricted,5 underlining the need for predictive biomarkers. Although luspatercept promotes late-stage erythropoiesis6 and may influence mesenchymal stromal cells,7 its full mechanism remains unclear.

Immune dysregulation is a key factor in MDS pathogenesis, contributing to ineffective hematopoiesis and AML progression.8 Early-stage MDS is marked by a proinflammatory bone marrow environment, with expanded cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes (CTLs)9 and reduced regulatory T cells (Tregs), defined by forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) transcription factor expression.10 In contrast, Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) expand in advanced disease.8 Recently, the immunosuppressive function of Tregs has been linked to expression of the exon-2–containing Foxp3 isoform (Foxp3-Ex2),11 and Treg frequency was proposed as a prognostic factor in MDS.12 The cytokine milieu shapes Treg and MDSC differentiation and function.13,14 TGF-β involvement in such processes and in modulating CTL function has been recognized.15,16

Given luspatercept interference with TGF-β–dependent pathways, it may affect the dysregulated immune microenvironment in MDS. Therefore, we analyzed a cohort of patients with MDS-RS treated with luspatercept, focusing on immunoregulatory populations (Tregs and MDSCs) and activation/proliferation of circulating immune effectors. We also evaluated whether baseline or dynamic immune profiles could predict treatment response.

Thirteen patients with MDS-RS eligible for luspatercept were enrolled between January 2021 and April 2023 at University of Naples Federico II and the Hospital “Andrea Tortora” in Pagani, Italy (clinical details in supplemental Table 1). All patients received luspatercept at 1 mg/kg, with response evaluated at 24 weeks (T1). An additional group of 7 long-term responders (median follow-up, 36 months) was included (T2). Further details are available in the supplemental Materials.

Circulating T, B, and natural killer lymphocyte percentages and counts were assessed at baseline (T0), after 24 weeks of luspatercept treatment (T1), and in long-term responders (T2) and compared with those of 20 age-/sex-matched healthy controls (CTRs). At T0 and T1, patients exhibited a significant reduction in total T lymphocyte percentage and counts of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared with those of CTRs (supplemental Figure 1A-C,F-H). Similar trends were observed for B and natural killer cells (supplemental Figure 1D-E,I,L). However, no significant changes in these lymphocyte populations were detected between T0 and T1, following luspatercept treatment.

Given the role of T cells in MDS pathogenesis9,17 and the influence of TGF-β on T-cell function,16 we analyzed the expressions of CD54, a marker of antigen-dependent T-cell activation,18 and the proliferation marker Ki6719 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at T0, T1, and T2. CD54 expression was significantly elevated in CD4+ T cells at both T0 and T1 compared with that in those of CTRs (supplemental Figure 2A-B); in contrast, CD54 expression in CD8+ T cells significantly increased after luspatercept treatment at T1 (supplemental Figure 2C-D). Ki67 expression showed a similar trend (supplemental Figure 2C-D)

Given that Tregs and MDSCs are implicated in impaired immune tolerance in MDS8,20,21 and TGF-β influences cell-mediated immune modulation,13-15 we analyzed circulating Tregs (focusing on the highly suppressive Foxp3-Ex2+ subset) and monocytic MDSCs22 (mMDSCs) before and after luspatercept treatment.

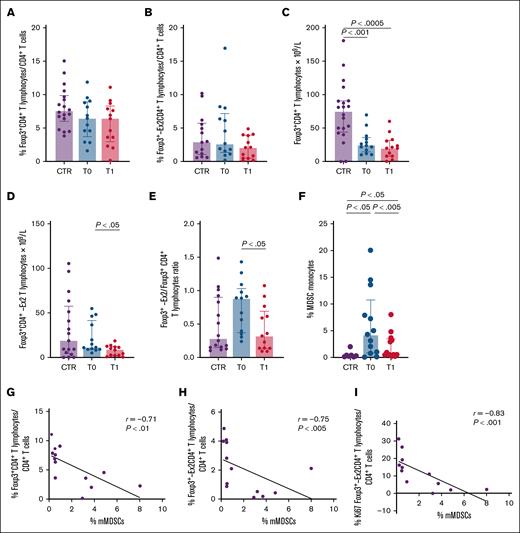

Foxp3+CD4+ and Foxp3-Ex2+CD4+ Treg percentages in patients with MDS-RS were comparable with those in CTRs (Figure 1A-B), but Foxp3+CD4+ Treg counts were significantly lower (Figure 1C). Conversely, luspatercept treatment reduced both Foxp3-Ex2+ Tregs and the Foxp3-Ex2/Foxp3 ratio (Figure 1D-E). To assess impact on Treg differentiation, we tested luspatercept in vitro on CD4+ T cells activated with TGF-β and found that luspatercept reduced TGF-β–induced Foxp3 expression (supplemental Figure 3).

Evaluation of circulating Tregs and mMDSC immune-regulatory subsets in patients with MDS-SR at baseline and after 24 weeks of luspatercept treatment. Purple, blue, and red columns indicate data obtained from healthy CTRs and from patients with MDS-SR before (T0) and after 24 weeks of luspatercept treatment (T1). The expression of the Foxp3-Ex2 transcription factor indicates highly effective Tregs (see text for details). (A-B) Percentage of circulating Tregs expressing Foxp3+ and Foxp3-Ex2+. (C-D) Number of circulating Tregs expressing Foxp3+ and Foxp3-Ex2+. (E) The Foxp3-Ex2/Foxp3 ratio. (F) Percentage of circulating mMDSCs. (G) Scatterplot analysis showing correlation between the frequencies of Foxp3-expressing Tregs and circulating mMDSCs in patients with MDS-SR at T1. (H) Scatterplot showing the correlation between the frequency of circulating Foxp3-Ex2+CD4+ Tregs and mMDSCs at T1. (I) Scatterplot showing the correlation between the frequencies of circulating Ki67+Foxp3-Ex2+CD4+ Tregs and mMDSCs at T1. For statistical evaluation details, see supplemental Materials.

Evaluation of circulating Tregs and mMDSC immune-regulatory subsets in patients with MDS-SR at baseline and after 24 weeks of luspatercept treatment. Purple, blue, and red columns indicate data obtained from healthy CTRs and from patients with MDS-SR before (T0) and after 24 weeks of luspatercept treatment (T1). The expression of the Foxp3-Ex2 transcription factor indicates highly effective Tregs (see text for details). (A-B) Percentage of circulating Tregs expressing Foxp3+ and Foxp3-Ex2+. (C-D) Number of circulating Tregs expressing Foxp3+ and Foxp3-Ex2+. (E) The Foxp3-Ex2/Foxp3 ratio. (F) Percentage of circulating mMDSCs. (G) Scatterplot analysis showing correlation between the frequencies of Foxp3-expressing Tregs and circulating mMDSCs in patients with MDS-SR at T1. (H) Scatterplot showing the correlation between the frequency of circulating Foxp3-Ex2+CD4+ Tregs and mMDSCs at T1. (I) Scatterplot showing the correlation between the frequencies of circulating Ki67+Foxp3-Ex2+CD4+ Tregs and mMDSCs at T1. For statistical evaluation details, see supplemental Materials.

The analysis of circulating mMDSCs revealed significant increase of their percentage in patients with MDS-RS at baseline compared with that in CTR, whereas luspatercept treatment was associated with a reduced level of mMDSCs (Figure 1F). We also analyzed the possible correlation between Tregs and mMDSCs. Confirming previous data in low-risk MDS,21 no significant correlation between such regulatory subsets was observed in our cohort at baseline (supplemental Figure 4). Conversely, luspatercept treatment was associated with a significant negative correlation between mMDSCs and both Foxp3+CD4+ and Foxp3-Ex2+CD4+ Tregs percentages (Figure 1G-H). In addition, we observed a negative correlation between the percentage of mMDSCs and the proliferation of Foxp3-Ex2+CD4+ T cells, as indicated by their Ki67 expression (Figure 1I). Previous studies suggested that MDSCs contribute to Treg expansion through TGF-β signaling15; however, the potential involvement of specific TGF-β ligands, possibly not targeted by luspatercept, warrants further investigation. The T1 immunological profile remained substantially stable in long-term responders (T2), as detailed in supplemental Table 2.

When baseline immunological parameters and clinical variables were compared, inverse correlations between Tregs and both time from MDS diagnosis to luspatercept treatment and median pretransfusion hemoglobin level were observed (supplemental Figures 5 and 6); conversely, significant positive correlations with percentage, amount, and activation status of CTL were revealed (supplemental Figure 6).

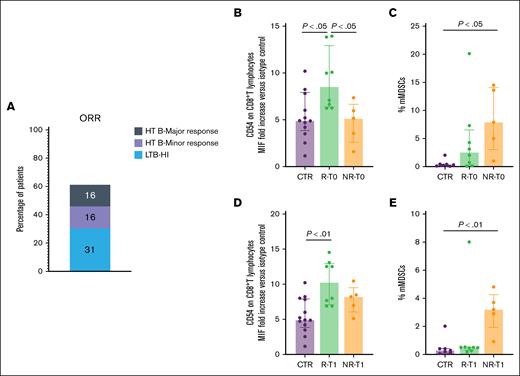

In our cohort, 1 patient achieved a complete response without dose escalation, 2 required an increase to 1.33 mg/kg, and 10 were escalated to 1.75 mg/kg. The evaluation of treatment response at 24 weeks (Figure 2A) revealed that 31% of patients with low transfusion burden and 16% with high transfusion burden achieved transfusion independence. In addition, 16% of patients showed minor responses, whereas 37% did not respond to therapy. In line with published results,4,5 a proportion of the patients did not reach a satisfying response to treatment. Few reports23 addressed the identification of reliable criteria to predict luspatercept response. The analysis of the baseline immune-profiles in our MDS-RS cohort, grouped according to luspatercept response, revealed a significant increase in CD54 expression on circulating CTLs in responders compared with that in both nonresponders and CTRs (Figure 2B-E). This elevated CD54 expression persisted following luspatercept treatment and was maintained at T2.

Response to luspatercept treatment of patients with MDS-SR is associated with CTL baseline activation. (A) Overall response rate in patients with MDS-RS undergoing luspatercept treatment at T1. Gray, purple, and blue levels indicate major response in HTB, minor response in HTB, and HI in LTB, respectively. (B-E) Purple, green, and orange columns indicate data obtained in healthy CTRs, MDS-SR responders, and MDS-SR nonresponders, respectively. (B,D) CD54 expression level in circulating CTLs of patients with MDS-SR at T0 (B) and T1 (D). (C,E) Percentage of circulating mMDSCs in patients with MDS-SR at T0 (C) and T1 (E). For statistical evaluation details, see the supplemental Materials. HI, hematological improvement; HTB, high transfusion burden; LTB, low transfusion burden; NR, nonresponder; ORR, overall response rate; R, responder.

Response to luspatercept treatment of patients with MDS-SR is associated with CTL baseline activation. (A) Overall response rate in patients with MDS-RS undergoing luspatercept treatment at T1. Gray, purple, and blue levels indicate major response in HTB, minor response in HTB, and HI in LTB, respectively. (B-E) Purple, green, and orange columns indicate data obtained in healthy CTRs, MDS-SR responders, and MDS-SR nonresponders, respectively. (B,D) CD54 expression level in circulating CTLs of patients with MDS-SR at T0 (B) and T1 (D). (C,E) Percentage of circulating mMDSCs in patients with MDS-SR at T0 (C) and T1 (E). For statistical evaluation details, see the supplemental Materials. HI, hematological improvement; HTB, high transfusion burden; LTB, low transfusion burden; NR, nonresponder; ORR, overall response rate; R, responder.

In addition, nonresponders exhibited significantly higher percentages of mMDSCs at both T0 and T1.

Immune dysregulation in MDS represents both a pathogenetic feature8 and an independent prognostic marker.8 In this study, we assessed the impact of luspatercept treatment on peripheral immune profiles in patients with MDS-RS, focusing on Tregs, mMDSCs, and T-cell activation before and after treatment and in long-term responders. Luspatercept treatment was associated with reduced levels of suppressive Tregs and mMDSCs, along with increased T-cell activation and proliferation.

Given the clinical need for predictive biomarkers, our data support previous findings linking higher lymphocyte counts to better outcomes23,24. Specifically, baseline immune profiles marked by low mMDSCs and enhanced CTL activation correlated with favorable responses to luspatercept.

Although derived from a relatively small cohort of patients with MDS-RS, our findings collectively suggest that luspatercept influences the immune-regulatory network likely via TGF-β–dependent pathway modulation, reducing suppressive subsets (Tregs and mMDSCs) and enhancing CTL activation/proliferation.

Persistent immune activation and reduced suppression were observed in long-term responders. Notably, baseline effective residual erythropoiesis was inversely correlated with immunosuppressive profiles, further reinforcing the prognostic value of immune parameters.

The pathogenic and clinical implications of these observations warrant further investigation and validation in larger, independent, MDS-RS cohorts.

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (no. 396/20). All patients and healthy CTRs provided written informed consent.

Acknowledgment: This research was funded by a Grant of Significant National Interest (Progetti di Ricerca di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale [PRIN] 2022) from the Italian Ministry for University and Research (grant 2022YZCBKX; G.T. and V.R.).

Contribution: S.L., F.G., G.T., G.R., and V.R. conceptualized the study; S.L., F.G., M.M., M.D.P., A.Vincenzi, G.C., F.P., and A.P. worked on the clinical data; S.L., G.S., A.Vassallo, G.T., F.C., and V.R. contributed to the methodology; S.L., F.G., G.S., A.P., G.T., G.R., F.C., and V.R. contributed in the original draft preparation; S.L., F.G., M.M., A.P., G.T., G.R., F.C., and V.R. helped in the review and editing of the manuscript; S.L., F.P., G.T., and V.R. contributed to funding acquisition; and all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.L. reports consultancy for Medac. F.P. reports speakers’ bureau role for GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Incyte, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Jazz, Novartis, and Pfizer; and consultancy for GSK and Incyte. A.P. reports speakers’ bureau role for Medac, Gilead, and Amgen; and advisory board role for Novartis and Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Valentina Rubino, Department of Translational Medical Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Via Sergio Pansini, 5, 80131 Naples, Italy; email: valentina.rubino@unina.it; and Flavia Carriero, Department of Sciences, University of Basilicata, Via dell'Ateneo Lucano, 10 - 85100. Potenza, Italy; email: flavia.carriero@unibas.it.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Valentina Rubino (valentina.rubino@unina.it).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.