TO THE EDITOR:

The treatment of follicular lymphoma (FL) is undergoing a revolutionary change as immunotherapies are increasingly explored. We recently reported the results of the phase 2 1st FLOR study exploring combination nivolumab and rituximab for patients with treatment-naïve FL (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03245021).1 Thirty-nine patients received 4 cycles of nivolumab (240 mg), then 4 cycles of biweekly nivolumab plus rituximab 375 mg/m2 (induction), then 1 year of monthly nivolumab (480 mg) plus 2 years of bimonthly rituximab maintenance. An overall response rate of 92% and a complete response (CR) of 59% was achieved. Four-year progression-free survival was 58% (95% confidence interval, 34-97) with high baseline tumor CD8a gene expression associated with improved progression-free survival. In a prespecified exploratory analysis, we examined peripheral blood (PB) immunology to examine changes that may predict for FL responses on trial.

Serial PB samples were analyzed for 34 of 39 enrolled patients at baseline, after 4 cycles of nivolumab (positron emission tomography–computed tomography 2 [PET-CT2]) and after maintenance cycle 5 (PET-CT4) and analyzed using a 29-antibody spectral flow cytometry panel as previously described,2 with data analyzed using FlowJo and Prism (supplemental Methods). Age-matched healthy donor samples (n = 12) were obtained from the Australian Red Cross Blood Service.

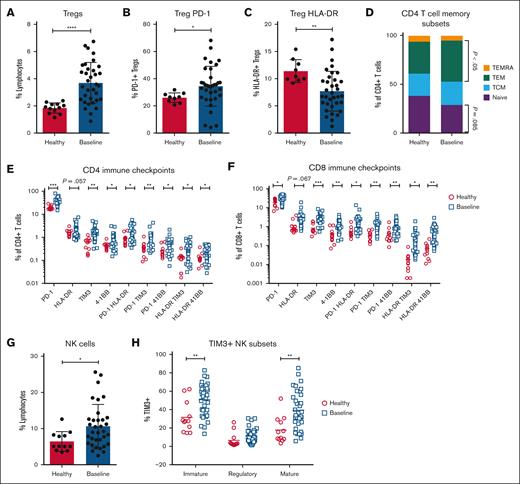

At baseline, there was no difference in B cell, monocyte, myeloid-derived suppressor cell, or dendritic cell populations (supplemental Figure 1) between patients and healthy donors. However, patients with FL exhibited an increase in CD25+CD127−CD4+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) (P < .0001; Figure 1A), with increased expression of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1; P < .05) and reduced proportions of activated (Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR [HLA-DR+]) Tregs (P < .01; Figure 1B-C). There was no difference in Lymphocyte-Activation Gene 3 (LAG-3), 4-1BB, Inducible T-cell Costimulator (ICOS), Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), Programmed death-ligand 2 (PD-L2), or T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM3) expression on Tregs (supplemental Figure 2).

Patients with FL exhibit significant changes in PB immune subsets at baseline. Spectral flow cytometry was used to assess PB immune subsets at study baseline (n = 34) compared with age-matched healthy donors (n = 12). Proportions of (A) CD25+CD127−CD4+ Tregs, (B) PD-1+ Tregs, (C) HLA-DR Tregs, (D) CD4 naïve (CCR7+CD45RA+), TCM (CCR7+CD45RA−), TEM (CCR7−CD45RA−), and TEMRA (CCR7−CD45RA+) T cells, expression of immune checkpoints across (E) CD4 and (F) CD8 T cells, (G) total NK cells, and (H) TIM3 expression on NK memory subsets. An unpaired t test with correction for multiple comparisons was performed for panels E-F,H. A Mann-Whitney U test was performed for all other graphs. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. TCM, Central Memory T cells; TEM, effector memory T cells; TEMRA, terminally differentiated T cells expressing CD45RA.

Patients with FL exhibit significant changes in PB immune subsets at baseline. Spectral flow cytometry was used to assess PB immune subsets at study baseline (n = 34) compared with age-matched healthy donors (n = 12). Proportions of (A) CD25+CD127−CD4+ Tregs, (B) PD-1+ Tregs, (C) HLA-DR Tregs, (D) CD4 naïve (CCR7+CD45RA+), TCM (CCR7+CD45RA−), TEM (CCR7−CD45RA−), and TEMRA (CCR7−CD45RA+) T cells, expression of immune checkpoints across (E) CD4 and (F) CD8 T cells, (G) total NK cells, and (H) TIM3 expression on NK memory subsets. An unpaired t test with correction for multiple comparisons was performed for panels E-F,H. A Mann-Whitney U test was performed for all other graphs. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. TCM, Central Memory T cells; TEM, effector memory T cells; TEMRA, terminally differentiated T cells expressing CD45RA.

Although proportions of CD4 and CD8 T cells in FL were similar to that of controls (supplemental Figure 3), they showed skewing toward an exhausted memory phenotype (Figure 1D), with increased expression of the immune checkpoints PD-1, HLA-DR, TIM3, and 4-1BB (Figure 1E-F). The proportions of natural killer (NK) cells were increased twofold in patients with FL (P < .05; Figure 1G). with increased TIM3 expression across immature (P < .01; CD56bright) and mature (P < .001; CD56dimCD16+) subsets (Figure 1H). These data indicate that treatment-naïve FL is associated with dysregulation of immune checkpoints across T and NK cells with additional changes in either the proportion or memory phenotype.

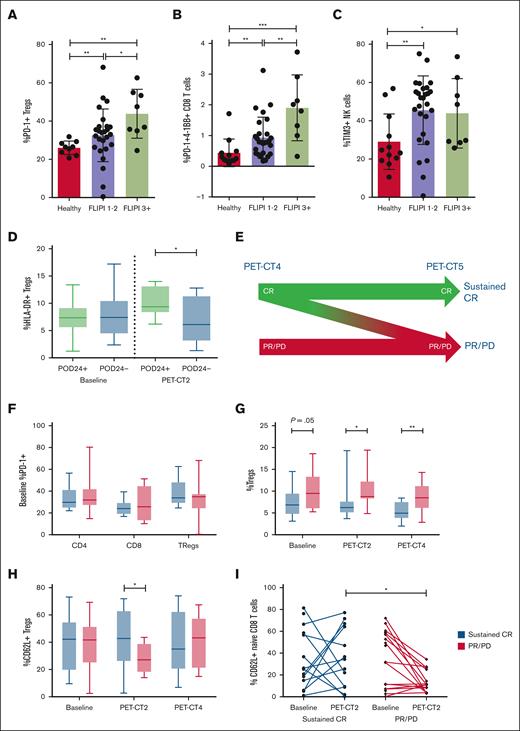

To explore the link between dysregulated PB immunology and baseline tumor characteristics, immune profiling data were correlated with the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI). Patients were classified into low-/intermediate-risk disease (FLIPI of 1-2; n = 26) vs high-risk disease (FILPI of ≥3; n = 8). High-risk disease was associated with increased proportions of PD-1+ Tregs (P < .05), HLA-DR+ CD4 (P < .05) and CD8 (P < .01) T cells, and coexpression of multiple checkpoints on CD8 T cells (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 4). TIM3+ NK cells were not different between low-/intermediate-risk and high-risk groups (Figure 2C). These results are consistent with previous reports of increased PD-1 expression on T cells3,4 and conversion to Tregs within the FL tumor microenvironment5,6 and indicate that the degree of PB immune dysregulation reflects disease prognosis.

Correlation between disease immunology, disease risk, and clinical treatment response. Patients were stratified into low/intermediate risk (FLIPI 1-2) and high risk (FLIPI ≥3) and correlation with immune profile explored across (A) PD-1+ Tregs, (B) PD-1+4-1BB+ CD8 T cells, and (C) TIM3+ NK cells. (D) Correlation between HLA-DR+ Tregs and POD24. (E) Patients were classified into sustained CR (achieved a CR by PET-CT4, which was maintained to PET-CT5 without evidence of relapse) and PR/PD (all other patients). (F) PD-1 expression across CD4, CD8, and Tregs stratified by durable response. Correlation between durability of response and immune profile over time for (G) Tregs, (H) CD62L+ Tregs, and (I) CD62L+ naïve CD8 T cells. A Mann-Whitney U test was performed for statistical analyses. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Correlation between disease immunology, disease risk, and clinical treatment response. Patients were stratified into low/intermediate risk (FLIPI 1-2) and high risk (FLIPI ≥3) and correlation with immune profile explored across (A) PD-1+ Tregs, (B) PD-1+4-1BB+ CD8 T cells, and (C) TIM3+ NK cells. (D) Correlation between HLA-DR+ Tregs and POD24. (E) Patients were classified into sustained CR (achieved a CR by PET-CT4, which was maintained to PET-CT5 without evidence of relapse) and PR/PD (all other patients). (F) PD-1 expression across CD4, CD8, and Tregs stratified by durable response. Correlation between durability of response and immune profile over time for (G) Tregs, (H) CD62L+ Tregs, and (I) CD62L+ naïve CD8 T cells. A Mann-Whitney U test was performed for statistical analyses. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

To examine the impact of nivolumab (with/without rituximab) on PB immunity, PB mononuclear cells were analyzed after 4 cycles of nivolumab induction (PET-CT2; n = 29) and after maintenance cycle 5 (PET-CT4; n = 31). Two patients achieved a CR on nivolumab monotherapy induction and continued monotherapy as maintenance, whereas the remaining patients received nivolumab + rituximab. Treatment was not associated with changes to CD4 or CD8 T-cell memory subsets or checkpoint expression (supplemental Figure 5). In contrast, Tregs significantly increased expression of PD-L2 (P < .0001) and LAG3 (P < .01) at PET-CT2 whereas TIM3 (P < .05) and PD-L1 (P < .01) expression was reduced (supplemental Figure 6). Although there was no change to the expression of 4-1BB or HLA-DR (supplemental Figure 6), when patients were stratified according to progression of disease within 24 months (POD24), patients with relapse/progression by 24 months (POD24+) had an increased proportion of activated (HLA-DR+) Tregs at PET-CT2 (P < .05; Figure 2D), at which time patients had only received 4 cycles of nivolumab and most patients had stable disease or a partial response (PR). These early changes in PB T-cell subsets represent a change in the tumor microenvironment that heralds long-term disease response.

At end of induction (PET-CT3), 59% of patients achieved a CR, with an overall response rate of 92%. However, responses continued to evolve past this point with many patients converting from PR to CR during nivolumab with/without rituximab maintenance whereas others either never achieved a CR or developed progressive disease (PD). Although POD24 is commonly used as a clinical end point in FL, we also wanted to assess correlations with disease response kinetics using an end point that incorporates both speed and durability of response. Therefore, patients were classified into sustained CR (achieved CR at PET-CT3 or PET-CT4, which was maintained to PET-CT5 without evidence of relapse; n = 15) and PR/PD (did not achieve a CR by PET-CT4 or developed PD by PET-CT5; n = 21; Figure 2E).

Despite being the target of nivolumab, PD-1 expression on T cells and Tregs at baseline did not correlate with response to nivolumab-rituximab therapy (Figure 2F). Rather, patients with sustained CR had a lower proportion of Tregs at baseline (P = .05), which decreased on treatment at PET-CT2 (P < .05) and PET-CT4 (P < .01) compared with patients with PR/PD (Figure 2G). At baseline, Tregs from patients with sustained CR had decreased expression of PD-L2 (P < .05) and a trend of increased TIM3 expression (supplemental Figure 7). Furthermore, patients with sustained CR had an increased proportion of naïve CD4 T cells at PET-CT4 (P < .05; supplemental Figure 7), suggesting that in the absence of tumor, CD4 T cells were no longer being converted to Tregs and normal Treg homeostasis was reestablished.

The homing of T cells to the tumor site is essential for anticancer responses to immunotherapy. L-selectin (CD62L) is a cell adhesion molecule found on the surface of leukocytes, which mediates homing to the lymph node and is shed upon activation. When examined in our cohort, we found that although the proportions of CD62L+ T cells were equivalent at baseline, there was maintenance of CD62L+ populations in patients with sustained CR whereas patients with PR/PD had significantly reduced CD62L+CD4 (P < .01), CD8 (P < .05), and Tregs (P < .05) at PET-CT2 in response to nivolumab monotherapy (Figure 2H; supplemental Figure 8). Importantly, CD62L expression was reduced on cytotoxic CD8 naïve T cells in PR/PD patients (P < .05) (Figure 2I). Through maintenance of a pool of CD62L+ cells in patients with sustained CR, T cells are likely able to traffic to tumor-containing lymph nodes and mediate a therapeutic response, indicating maintenance of CD62L expression is an early biomarker of durable response to nivolumab-rituximab therapy.

We explored the impact of FL on PB immune subsets at diagnosis and after nivolumab with/without rituximab therapy. We identified widespread impacts in treatment-naïve FL across T-cell and NK cell subsets, with changes in memory phenotype and increased expression of multiple immune checkpoints. Further exploration of FL PB immunology is warranted to improve the use and effectiveness of novel emerging immunotherapies.

Acknowledgments: The authors acknowledge the Melbourne Cytometry Platform for access to flow cytometric instruments.

Bristol Myers Squibb provided study funding and nivolumab. C.K. and E.A.H. were supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) investigator grants (2017033 and 2020/MRF1194324).

Contribution: R.M.K., D.S.R., and E.A.H. designed the study; C.S. was responsible for data collection; R.M.K., A.B., H.M., S.T.L., and N.H. were responsible for data collection and analysis; R.M.K. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.B. reports honoraria from, or advisory board role with, BeiGene, Novartis, Gilead, and Roche. G.C. reports consulting role with Regeneron, Takeda, and Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS); and research funding from Hutchmed, Regeneron, BMS, Seagen, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Roche, Bayer, Pharmacyclics, Incyte, Dizal Pharma, Innate Pharma, and Merck. D.L. reports honoraria from, or advisory roles with, Roche and Gilead. C.K. reports consulting role with Takeda, Merck, Roche, Gilead, and AstraZeneca. E.A.H. reports research funding (paid to institution) from Roche, BMS, Merck KgaA, AstraZeneca, TG Therapeutics, and Merck; reports consultant or advisory roles with Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme, AstraZeneca, Antengene, Novartis, Janssen, Specialised Therapeutics, Sobi (all paid to institution), Regeneron, and Gilead; and received travel expenses from AstraZeneca. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rachel M. Koldej, ACRF Translational Research Laboratory, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Laboratory Cluster 3, Level 10, 305 Grattan St, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia; email: rachel.koldej@mh.org.au.

References

Author notes

D.S.R. and E.A.H. contributed equally to this study.

Primary results were presented, in part, at the 66th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 7 to 10 December 2024.

Requests for nonidentifiable data with valid academic reasons as judged by the trial management group will be granted, with appropriate data sharing agreement, and should be addressed to the corresponding author, Rachel M. Koldej (rachel.koldej@mh.org.au). Data will be made available 3 months after publication for a period of 5 years after the publication. Individual participant data will not be shared.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.