Key Points

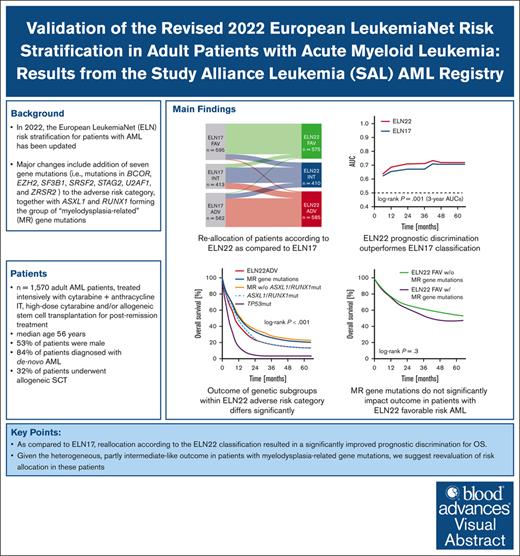

Reclassification according to the ELN22 recommendations resulted in significantly improved prognostic discrimination for OS.

Given the heterogeneous outcome in patients with myelodysplasia-related gene mutations, we suggest reevaluation of risk allocation in these patients.

Visual Abstract

In 2022, the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) risk stratification for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has been updated. We aimed to validate the prognostic value of the 2022 ELN classification (ELN22) by evaluating 1570 patients with newly diagnosed AML (median age, 56 years) treated with cytarabine-based intensive chemotherapy regimens. Compared with 2017 ELN classification (ELN17), which allocated 595 (38%), 413 (26%), and 562 patients (36%) to the favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk categories, ELN22 classified 575 (37%), 410 (26%), and 585 patients (37%) as favorable, intermediate, and adverse risk, respectively. Risk group allocation was revised in 340 patients (22%). Most patients were reclassified into the ELN22 intermediate- or ELN22 adverse-risk group. The allocation of patients according to the ELN22 risk categories resulted in a significantly distinct event-free survival (EFS), relapse-free survival, and overall survival (OS). Compared with ELN17, reallocation according to the ELN22 recommendations resulted in a significantly improved prognostic discrimination for OS (3-year area under the curve, 0.71 vs 0.67). In patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML, co-occurring myelodysplasia-related (MR) gene mutations did not significantly affect outcomes. Within the ELN22 adverse-risk group, we observed marked survival differences across mutational groups (5-year OS rate of 21% and 3% in patients with MR gene mutations and TP53 mutations, respectively). In patients harboring MR gene mutations, EZH2-, STAG2-, and ZRSR2-mutated patients showed an intermediate-like OS. In patients with secondary AML and those who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, EFS and OS significantly differed between ELN22 risk groups, whereas the prognostic abilities of ELN17 and ELN22 classifications were similar. In conclusion, ELN22 improves prognostic discrimination in a large cohort of intensively treated patients with AML. Given the heterogeneous outcome in patients with MR gene alterations, ranging between those of intermediate and adverse risk patients, we suggest re-evaluation of risk allocation in these patients.

Introduction

In 2010, an international expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) introduced recommendations for the diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in adults, including a risk stratification based on cytogenetic aberrations and selected gene mutations (ie, mutations in CEBPA, FLT3, and NPM1).1 Due to advances in the discovery of the genomic landscape of the disease and novel therapeutic approaches, the ELN guidelines were updated in 2017.2 Here, the risk classification was modified by considering only biallelic CEBPA mutations as prognostically favorable, implementing the FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) allelic ratio (AR) as a risk factor, and adding ASXL1, RUNX1, and TP53 mutations as adverse risk markers. Both 2010 and 2017 ELN classifications (ELN10 and ELN17, respectively) were validated in large patient cohorts and found widespread adoption in routine practice and clinical trials.3-5 In 2022, the ELN risk stratification for patients with AML was updated once again. Major changes compared with ELN17 include the substitution of biallelic CEBPA mutations with in-frame mutations affecting the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain of the CEBPA gene as a favorable-risk feature and the consideration of patients with FLT3-ITD as intermediate risk, irrespective of the AR or NPM1 comutations. Furthermore, 7 gene mutations (ie, mutations in BCOR, EZH2, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2) were added, together with ASXL1 and RUNX1 forming the group of “myelodysplasia-related” (MR) gene mutations.6,7 The evidence of MR gene mutations (also known as secondary-type mutations [not including RUNX1]) confers allocation to the adverse-risk category when not accompanied with favorable-risk alterations. Additional changes include the placement of patients with NPM1 mutations but with the presence of adverse cytogenetic aberrations (eg, –7 or complex karyotype) as well as patients with t(8;16)(p11.2;p13.3)/KAT6A::CREBBP and t(3;v)(q26.2;v)/MECOM(EVI1) rearrangements in the adverse-risk group, whereas patients with hyperdiploid karyotypes with ≥3 trisomies without additional structural abnormalities are no longer considered adverse risk. Previous studies8-18 evaluating the revised 2022 risk classification (ELN22) are based on heterogeneously treated patient cohorts receiving various therapy regimens, including intensive chemotherapy (IC),8-14,17 low-dose cytarabine,12 hypomethylating agents (HMAs)/HMA and venetoclax,8,12,14,17,18 and/or investigational agents.8,9,11,12 Accordingly, we aimed to validate the prognostic value of the ELN22 recommendations in a large patient cohort, treated intensively with cytarabine-based chemotherapy regimens.

Methods

We evaluated 1570 patients aged ≥18 years with newly diagnosed AML. The majority of patients were treated within 4 randomized-controlled trials of the Study Alliance Leukemia between 1996 and 2016 (AML96 trial [NCT00180115], n = 935 patients; AML60+ trial [NCT00180167], n = 42 patients; AML2003 trial [NCT00180102], n = 182 patients; and SORAML trial [NCT00893373], n = 221 patients). All patients were intensively treated with cytarabine- and anthracycline/mitoxantrone-based induction chemotherapy. For consolidation, patients received either high-dose cytarabine or autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Patients treated within the verum group of the SORAML trial additionally received sorafenib during induction, postremission treatment, as well as maintenance therapy. Detailed treatment regimens are published in previous reports.19-22

Cytogenetic analyses (Giemsa-banding and fluorescence in situ hybridization) were performed by 1 of the Study Alliance Leukemia reference laboratories. Testing for FLT3-ITD as well as CEBPA and NPM1 mutations was done centrally using fragment length analysis.23-25 Furthermore, panel next-generation sequencing was performed targeting a set of genes commonly altered in myeloid neoplasms. The limit of detection was 1% variant allele frequency (VAF); variants were reported and classified according to the consensus recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and College of American Pathologists.26

Data were collected under an institutional review board–approved protocol of the Technische Universität Dresden (EK 210396, EK153092003, JU-EK-AMG-87/2004, and EK276112008). The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.3. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher exact or χ2 tests, whereas continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. Survival outcomes were assessed by time-to-event analyses using the log-rank method, with Cox proportional hazard modeling, as appropriate. For comparisons of the predictive values of ELN22 and ELN17, we used receiver operating characteristics (ROCs).

Results

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics within the ELN22 risk categories

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of all 1570 patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 56 years (range, 18-89), and 47% were female. Most patients (84%) were diagnosed with de novo AML, whereas secondary AML and therapy-related AML was seen in 12% and 4%, respectively. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) was performed in 504 patients (32%), of whom 238 patients received alloHCT in first remission. ELN22 risk was favorable, intermediate, and adverse risk in 575 (37%), 410 (26%), and 585 patients (37%), respectively. Patients with ELN22 adverse risk were significantly older (median, 61 years) than patients classified as ELN22 favorable or intermediate risk (median, 51 and 55 years, respectively; P < .001). In addition, patients assigned to the ELN22 adverse-risk category were more likely to have secondary AML (22% vs 4% and 11%; P < .001), had lower white blood cell (WBC) counts (median, 9.3 × 109/L vs 27.5 × 109/L and 23.4 × 109/L; P < .001), and lower peripheral blood as well as bone marrow blast counts (56% vs 63% and 68%; P < .001) than patients with ELN22 favorable and intermediate risks. Among 571 patients aged ≥60 years, 135 (24%) were classified as ELN22 favorable, 140 (25%) as ELN22 intermediate, and 296 (52%) as ELN22 adverse risk, according to the ELN22 recommendations (supplemental Table 1).

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of all patients within the ELN22 risk categories

| . | ELN22 FAV (n = 575) . | ELN22 INT (n = 410) . | ELN22 ADV (n = 585) . | Total (N = 1570) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELN17, n (%) | <.001 | ||||

| FAV | 502 (87.3%) | 79 (19.3%) | 14 (2.4%) | 595 (37.9%) | |

| INT | 60 (10.4%) | 255 (62.2%) | 98 (16.8%) | 413 (26.3%) | |

| ADV | 13 (2.3%) | 76 (18.5%) | 473 (80.9%) | 562 (35.8%) | |

| Age, y | <.001 | ||||

| Median | 51 | 55 | 61 | 56 | |

| Range | 18-85 | 18-85 | 18-89 | 18-89 | |

| Sex, n (%) | .671 | ||||

| Female | 272 (47.3%) | 201 (49.0%) | 270 (46.2%) | 743 (47.3%) | |

| Male | 303 (52.7%) | 209 (51.0%) | 315 (53.8%) | 827 (52.7%) | |

| ECOG | .045 | ||||

| miss, n | 92 | 66 | 107 | 265 | |

| >1, n (%) | 122 (25.3%) | 110 (32.0%) | 151 (31.6%) | 383 (29.3%) | |

| 0-1, n (%) | 361 (74.7%) | 234 (68.0%) | 327 (68.4%) | 922 (70.7%) | |

| AML ontogeny | <.001 | ||||

| miss, n | 3 | 4 | 11 | 18 | |

| de novo, n (%) | 539 (94.2%) | 351 (86.5%) | 415 (72.3%) | 1305 (84.1%) | |

| sAML, n (%) | 22 (3.8%) | 43 (10.6%) | 128 (22.3%) | 193 (12.4%) | |

| tAML, n (%) | 11 (1.9%) | 12 (3.0%) | 31 (5.4%) | 54 (3.5%) | |

| WBC, ×109/L | <.001 | ||||

| Median | 27.5 | 23.3 | 9.2 | 18.20 | |

| Range | 0.3-453.0 | 0.6-465.9 | 0.3-450.0 | 0.3-465.9 | |

| Hb, mmol/L | .039 | ||||

| Median | 5.90 | 5.95 | 5.80 | 5.897 | |

| Range | 2.35-12.90 | 2.29-14.50 | 2.30-15.60 | 2.29-15.60 | |

| PLT, ×109/L | .001 | ||||

| Median | 43 | 58 | 51 | 50 | |

| Range | 3-554 | 3-514 | 4-1043 | 3-1043 | |

| BMBs | <.001 | ||||

| Median, % | 63 | 68 | 56 | 62 | |

| Range, % | 6-96 | 8-100 | 5-100 | 5-100 | |

| PBBs | <.001 | ||||

| Median, % | 45 | 46 | 28 | 39 | |

| Range, % | 0-100 | 0-99 | 0-99 | 0-100 | |

| alloHCT | .052 | ||||

| All pts., n (%) | 179 (31.1%) | 151 (36.8%) | 174 (29.6%) | 504 (32.0%) | |

| CR1, n (%) | 96 (16.7%) | 70 (17.1%) | 72 (12.3%) | 238 (15.2%) | |

| Salvage, n (%) | 76 (13.2%) | 65 (15.9%) | 74 (12.6%) | 215 (13.7%) |

| . | ELN22 FAV (n = 575) . | ELN22 INT (n = 410) . | ELN22 ADV (n = 585) . | Total (N = 1570) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELN17, n (%) | <.001 | ||||

| FAV | 502 (87.3%) | 79 (19.3%) | 14 (2.4%) | 595 (37.9%) | |

| INT | 60 (10.4%) | 255 (62.2%) | 98 (16.8%) | 413 (26.3%) | |

| ADV | 13 (2.3%) | 76 (18.5%) | 473 (80.9%) | 562 (35.8%) | |

| Age, y | <.001 | ||||

| Median | 51 | 55 | 61 | 56 | |

| Range | 18-85 | 18-85 | 18-89 | 18-89 | |

| Sex, n (%) | .671 | ||||

| Female | 272 (47.3%) | 201 (49.0%) | 270 (46.2%) | 743 (47.3%) | |

| Male | 303 (52.7%) | 209 (51.0%) | 315 (53.8%) | 827 (52.7%) | |

| ECOG | .045 | ||||

| miss, n | 92 | 66 | 107 | 265 | |

| >1, n (%) | 122 (25.3%) | 110 (32.0%) | 151 (31.6%) | 383 (29.3%) | |

| 0-1, n (%) | 361 (74.7%) | 234 (68.0%) | 327 (68.4%) | 922 (70.7%) | |

| AML ontogeny | <.001 | ||||

| miss, n | 3 | 4 | 11 | 18 | |

| de novo, n (%) | 539 (94.2%) | 351 (86.5%) | 415 (72.3%) | 1305 (84.1%) | |

| sAML, n (%) | 22 (3.8%) | 43 (10.6%) | 128 (22.3%) | 193 (12.4%) | |

| tAML, n (%) | 11 (1.9%) | 12 (3.0%) | 31 (5.4%) | 54 (3.5%) | |

| WBC, ×109/L | <.001 | ||||

| Median | 27.5 | 23.3 | 9.2 | 18.20 | |

| Range | 0.3-453.0 | 0.6-465.9 | 0.3-450.0 | 0.3-465.9 | |

| Hb, mmol/L | .039 | ||||

| Median | 5.90 | 5.95 | 5.80 | 5.897 | |

| Range | 2.35-12.90 | 2.29-14.50 | 2.30-15.60 | 2.29-15.60 | |

| PLT, ×109/L | .001 | ||||

| Median | 43 | 58 | 51 | 50 | |

| Range | 3-554 | 3-514 | 4-1043 | 3-1043 | |

| BMBs | <.001 | ||||

| Median, % | 63 | 68 | 56 | 62 | |

| Range, % | 6-96 | 8-100 | 5-100 | 5-100 | |

| PBBs | <.001 | ||||

| Median, % | 45 | 46 | 28 | 39 | |

| Range, % | 0-100 | 0-99 | 0-99 | 0-100 | |

| alloHCT | .052 | ||||

| All pts., n (%) | 179 (31.1%) | 151 (36.8%) | 174 (29.6%) | 504 (32.0%) | |

| CR1, n (%) | 96 (16.7%) | 70 (17.1%) | 72 (12.3%) | 238 (15.2%) | |

| Salvage, n (%) | 76 (13.2%) | 65 (15.9%) | 74 (12.6%) | 215 (13.7%) |

ADV, adverse; BMBs, bone marrow blasts; CR1, first CR; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FAV, favorable; Hb, hemoglobin; INT, intermediate; PBBs, peripheral blood blasts; PLT, platelet count; sAML, secondary AML; tAML, therapy-related AML; miss, missing.

Distribution of ELN22 risk-defining alterations

The majority of patients harbored 1 (42%) or 2 ELN22 risk-defining alterations (34%). Patients assigned to the ELN22 adverse-risk group had more risk-defining abnormalities (median, 3 [range, 1-6]) than patients classified as favorable (median, 1 [range, 1-4]) or intermediate risk (median, 1 [range, 0-4]). In 174 patients, no ELN22 risk-defining alterations were identified.

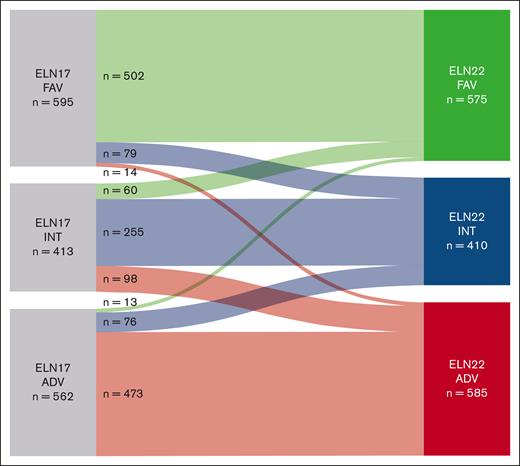

Comparison of ELN17 and ELN22 risk stratifications

According to the ELN22 recommendations, risk group allocation was revised in 340 patients (22%). In our cohort, 13% of patients previously assigned to the favorable-risk category, 38% of patients classified as intermediate risk, and 19% of patients assigned to the adverse-risk group were reclassified (Figure 1). Most patients were reclassified into ELN22 intermediate- (n = 155 [46%]) or ELN22 adverse-risk group (n = 112 [33%]). Reassignment of patients previously classified as favorable risk according to ELN17 to the ELN22 intermediate-risk group was commonly due to evidence of low AR FLT3-ITD mutations with NPM1 comutation. Patients who were previously classified as intermediate risk and reassigned to the ELN22 favorable-risk group mainly harbored CEBPA bZIP in-frame mutations, whereas patients who were previously classified as intermediate risk and reassigned to the ELN22 adverse-risk group frequently had evidence of MR gene mutations (BCOR, EZH2, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, or ZRSR2 mutations). Most patients reclassified as ELN22 intermediate risk, previously assigned to the ELN17 adverse-risk group, harbored high AR FLT3-ITD mutations without NPM1 comutations.

Sankey plot showing reallocation of patients in ELN22 compared with ELN17. ADV, adverse; FAV, favorable; INT, intermediate.

Sankey plot showing reallocation of patients in ELN22 compared with ELN17. ADV, adverse; FAV, favorable; INT, intermediate.

Overall, however, there were only slight net effects on the percentage of patients classified as ELN22 favorable, ELN22 intermediate, and ELN22 adverse risk (–1%, –3%, and +4%, respectively).

Outcome of patients classified according to ELN22

The composite complete remission (CR) rate, which is CR + CRi, across all ELN22 risk categories was 70%. Patients assigned to the favorable- and intermediate-risk groups had comparable CR rates (87% and 77%, respectively), whereas patients classified as adverse risk had significantly lower CR rates (49%; P < .001; Table 2).

Outcomes according to the ELN22 risk categories

| ELN22 risk category . | CR rate . | EFS . | RFS . | OS . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | P value . | 5-y EFS rate, % (95% CI) . | P value . | 5-y RFS rate, % (95% CI) . | P value . | 5-y OS rate, % (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| All patients (N = 1570) | ||||||||

| ELN22 FAV (N = 575) | 502 (87.3) | <.001 | 40 (36-44) | <.001 | 49 (45-54) | <.001 | 53 (49-57) | <.001 |

| ELN22 INT (N = 410) | 314 (76.6) | 21 (18-26) | 32 (27-38) | 32 (28-37) | ||||

| ELN22 ADV (N = 585) | 288 (49.2) | 7.8 (5.8-10) | 23 (18-28) | 13 (11-17) | ||||

| Age ≤60 y (n = 999) | ||||||||

| ELN22 FAV (N = 440) | 403 (91.6) | <.001 | 48 (44-53) | <.001 | 56 (51-61) | <.001 | 63 (58-68) | <.001 |

| ELN22 INT (N = 270) | 224 (83.0) | 29 (24-35) | 39 (33-46) | 42 (36-48) | ||||

| ELN22 ADV (N = 289) | 195 (67.5) | 14 (11-19) | 30 (24-38) | 24 (19-30) | ||||

| Age >60 y (n = 571) | ||||||||

| ELN22 FAV (N = 135) | 99 (73.3) | <.001 | 14 (8.9-21) | <.001 | 22 (15-32) | <.001 | 22 (16-31) | <.001 |

| ELN22 INT (N = 140) | 90 (64.3) | 7.3 (4.0-13) | 17 (11-27) | 15 (10-22) | ||||

| ELN22 ADV (N = 296) | 93 (31.4) | 1.9 (0.8-4.4) | 7.8 (3.8-16) | 3.5 (1.9-6.5) | ||||

| ELN22 risk category . | CR rate . | EFS . | RFS . | OS . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | P value . | 5-y EFS rate, % (95% CI) . | P value . | 5-y RFS rate, % (95% CI) . | P value . | 5-y OS rate, % (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| All patients (N = 1570) | ||||||||

| ELN22 FAV (N = 575) | 502 (87.3) | <.001 | 40 (36-44) | <.001 | 49 (45-54) | <.001 | 53 (49-57) | <.001 |

| ELN22 INT (N = 410) | 314 (76.6) | 21 (18-26) | 32 (27-38) | 32 (28-37) | ||||

| ELN22 ADV (N = 585) | 288 (49.2) | 7.8 (5.8-10) | 23 (18-28) | 13 (11-17) | ||||

| Age ≤60 y (n = 999) | ||||||||

| ELN22 FAV (N = 440) | 403 (91.6) | <.001 | 48 (44-53) | <.001 | 56 (51-61) | <.001 | 63 (58-68) | <.001 |

| ELN22 INT (N = 270) | 224 (83.0) | 29 (24-35) | 39 (33-46) | 42 (36-48) | ||||

| ELN22 ADV (N = 289) | 195 (67.5) | 14 (11-19) | 30 (24-38) | 24 (19-30) | ||||

| Age >60 y (n = 571) | ||||||||

| ELN22 FAV (N = 135) | 99 (73.3) | <.001 | 14 (8.9-21) | <.001 | 22 (15-32) | <.001 | 22 (16-31) | <.001 |

| ELN22 INT (N = 140) | 90 (64.3) | 7.3 (4.0-13) | 17 (11-27) | 15 (10-22) | ||||

| ELN22 ADV (N = 296) | 93 (31.4) | 1.9 (0.8-4.4) | 7.8 (3.8-16) | 3.5 (1.9-6.5) | ||||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ADV, adverse; CR, complete remission; EFS, event-free survival; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; FAV, favorable; INT, intermediate; OS. overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

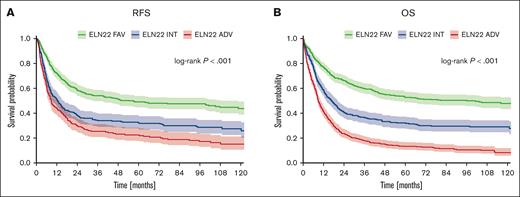

After a median follow-up of 83 months, the allocation of patients according to the novel ELN22 risk categories resulted in a statistically significantly distinct event-free survival (EFS), relapse-free survival (RFS), and overall survival (OS). The 5-year EFS rates for patients in the favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk categories were 40%, 21%, and 8%; 5-year RFS rates were 49%, 32%, and 23%; and 5-year OS rates were 53%, 32%, and 13%, respectively (Figure 2). Survival outcomes also significantly differed when patients aged ≤60 years and older patients were analyzed separately (Table 2; supplemental Figure 1).

Outcome of patients (N = 1570) stratified according to the ELN22 recommendations. (A) RFS. (B) OS.

Outcome of patients (N = 1570) stratified according to the ELN22 recommendations. (A) RFS. (B) OS.

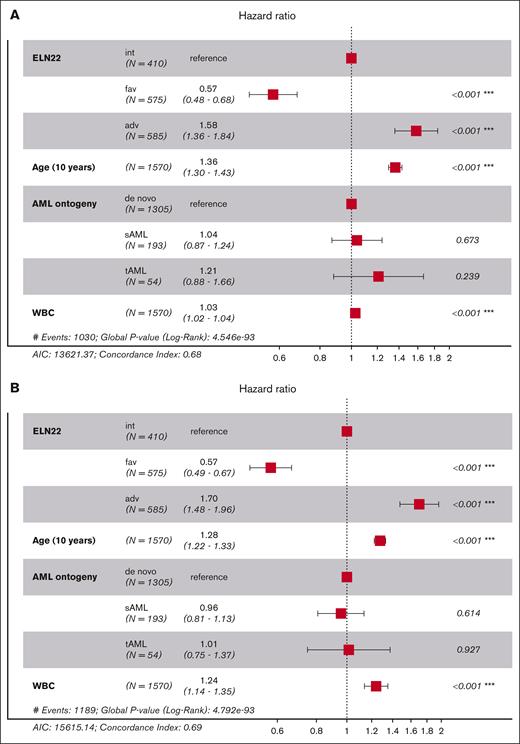

In multivariable models assessing factors/confounders associated with OS, such as age and WBC, ELN favorable risk was associated with longer survival, whereas adverse risk, older age, and higher WBC were associated with shorter survival. Those same factors also associated with survival in a multivariable model for EFS and RFS. In contrast, AML ontogeny (de novo vs secondary AML) did not affect patient outcomes when accounting for genetic risk factors (Figure 3).

Multivariate analyses of outcomes according to the ELN22 risk stratification. Forest plot showing hazard ratios from a Cox proportional hazards model for OS (A), EFS (B), and RFS (C). AIC, Akaike information criterion.

Multivariate analyses of outcomes according to the ELN22 risk stratification. Forest plot showing hazard ratios from a Cox proportional hazards model for OS (A), EFS (B), and RFS (C). AIC, Akaike information criterion.

Outcomes according to different molecular features within the ELN22 risk categories

To further elucidate the prognostic impact of newly incorporated molecular alterations, we reevaluated the ELN22 risk categories separately.

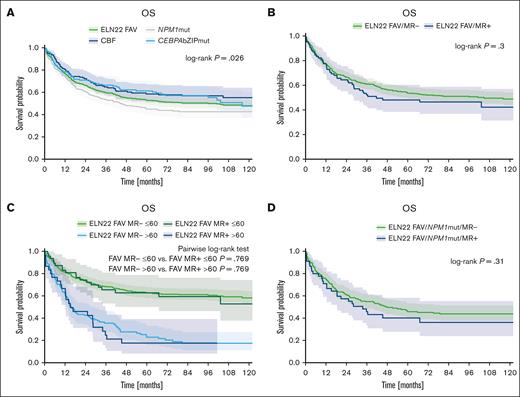

Within the ELN22 favorable-risk group, patients with core-binding factor (CBF) AML or evidence of CEBPA bZIP in-frame mutations showed superior survival (median OS [mOS], not reached and 116 months; corresponding 5-year OS rate, 59% and 61%, respectively) compared with patients with NPM1 mutations (without additional alterations leading to allocation to intermediate- or adverse-risk group such as FLT3-ITD or cytogenetic aberration considered adverse risk), who achieved an mOS of 45 months with a corresponding 5-year OS rate of 45% (P = .026; Figure 4A). The outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML also harboring MR gene mutations (ie, mutations in ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2) was numerically worse than the outcome of patients without MR gene mutations; however, the differences were not statically significant (CR rate, 84% vs 88%; P = .257; mOS, 42 months vs 105 months; corresponding 5-year OS rate, 48% vs 54%; P = .3; Figure 4B). There were also no statistically significant differences in outcome between patients with and without MR gene mutations when stratifying for age (≤/>60 years; for patients aged ≤60 years, mOS, not reached vs not reached; corresponding 5-year OS rate, 63% vs 63%; P = .769; for patients >60 years, mOS, 15 months vs 16 months; corresponding 5-year OS rate, 18% vs 23%; P = .769; Figure 4C) or MR gene mutations VAF (≤/> median VAF; mOS, 34 months vs 103 months; corresponding 5-year OS rate, 48% vs 56%; P = .24). Furthermore, the outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML with NPM1 mutations with or without MR gene mutations did not significantly differ (mOS, 34 months vs 48 months; corresponding 5-year OS rate, 40% vs 46%; P = .31; Figure 4D).

Outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML. (A) Outcome of patients with NPM1 mutations, patients with CBF leukemia and patients with CEBPA bZIP in-frame mutations within the ELN22 favorable risk category. (B) Outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML with or without MR gene comutations (ie, mutations in ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2). (C) Outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML with or without MR gene comutations, stratified by age (≤/>60 years). (D) Outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk NPM1-mutated AML with or without MR gene mutations. mut, mutated.

Outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML. (A) Outcome of patients with NPM1 mutations, patients with CBF leukemia and patients with CEBPA bZIP in-frame mutations within the ELN22 favorable risk category. (B) Outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML with or without MR gene comutations (ie, mutations in ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2). (C) Outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML with or without MR gene comutations, stratified by age (≤/>60 years). (D) Outcome of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk NPM1-mutated AML with or without MR gene mutations. mut, mutated.

Within the ELN22 adverse-risk group, we observed significant survival differences across mutational groups. Although the mOS and 5-year OS rate of the entire ELN22 adverse-risk group was 9 months and 13%, respectively, the outcome in TP53-mutated patients was worse (mOS, 5 months; 5-year OS rate, 3%), whereas patients with MR gene mutations (ie, mutations in ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2) showed better survival (mOS, 14 months; 5-year OS rate, 21%; P < .001; Figure 5A). Within the subgroup of patients with MR gene mutations, the outcome of patients with ASXL1 and/or RUNX1 mutations was worse than the outcome of patients with MR gene mutation other than ASXL1 and/or RUNX1 (mOS, 11 months vs 14 months; corresponding 5-years OS rate, 13% vs 23%; P = .011; Figure 5B). Furthermore, when assessing the impact of MR gene mutation VAFs, we observed a trend for better OS in patients with MR gene mutation VAF less than or equal to the median VAF than those with MR gene mutation VAF greater than median VAF (mOS, 17 months vs 11 months; corresponding 5-year OS rate, 21% vs 20%; P = .082; Figure 5C). Notably, we observed a wide range in terms of OS according to the affected genes in MR gene–mutated patients. Although patients with EZH2, STAG2, or ZRSR2 mutations achieved mOS of 18 months, 21 months, and 32 months with corresponding 5-year OS rates of 30%, 34% and 33%, respectively, the mOS and 5-year OS rate in patients with U2AF1 variants was only 10 months and 5%, respectively (P < .001; Figure 5D).

Outcome of patients with ELN22 adverse risk AML. (A) Outcome of patients with MR gene mutations (ie, mutations in ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2) compared with patients with TP53 mutations within the ELN22 adverse-risk group. (B) Outcome of patients with ASXL1 and/or RUNX1 mutations and patients with MR gene mutations other than ASXL1 and/or RUNX1 within the ELN22 adverse-risk category. (C) Outcome of patients with MR gene mutations, stratified by MR gene mutation VAF. (D) Outcome of patients with evidence of mutations in EZH2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2. w/o, without.

Outcome of patients with ELN22 adverse risk AML. (A) Outcome of patients with MR gene mutations (ie, mutations in ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2) compared with patients with TP53 mutations within the ELN22 adverse-risk group. (B) Outcome of patients with ASXL1 and/or RUNX1 mutations and patients with MR gene mutations other than ASXL1 and/or RUNX1 within the ELN22 adverse-risk category. (C) Outcome of patients with MR gene mutations, stratified by MR gene mutation VAF. (D) Outcome of patients with evidence of mutations in EZH2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2. w/o, without.

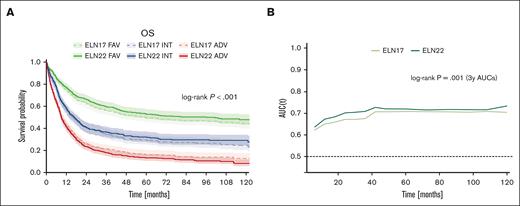

Performance of the ELN22 risk stratification

The 5-year OS rates for patients in the ELN22 favorable-, ELN22 intermediate-, and ELN22 adverse-risk category were 53%, 32%, and 13%, whereas the corresponding 5-year OS rates in patients classified according to ELN17 were 49%, 30% and 16%, respectively (Figure 6A). Thus, the ELN22 risk stratification more accurately stratified OS in patients assigned to the favorable- and adverse-risk categories. Furthermore, compared with ELN17, reclassification according to the ELN22 recommendations resulted in improved prognostic discrimination for OS (2-year area under the curve, 0.70 vs 0.67; P = .003; 3-year area under the curve, 0.71 vs 0.67; P = .001), as evaluated by inverse-probability-of-censoring weighting and area under time-dependent ROC curves (Figure 6B).

Performance of the revised ELN22 classification. (A) Comparison of outcome in patients stratified by either ELN17 or ELN22. (B) Comparison of time-dependent ROC curves for OS between ELN17 and ELN22.

Performance of the revised ELN22 classification. (A) Comparison of outcome in patients stratified by either ELN17 or ELN22. (B) Comparison of time-dependent ROC curves for OS between ELN17 and ELN22.

Prognostic value of the ELN22 risk classification in patients with secondary AML (AML with history of antecedent MDS or MDS/MPN)

One hundred and ninety-three patients were diagnosed with AML progressing from myelodysplastic neoplasms (MDS) or myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPN). Baseline characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table 2; the median age was 63 years (range, 24-86), and 56% of patients were male. ELN22 risk was favorable, intermediate, and adverse in 22 patients (12%), 43 patients (22%), and 128 patients (66%), respectively. Compared with the ELN17 risk stratification, 14% of patients previously assigned to the favorable-risk category, 33% of patients classified as intermediate risk, and 15% of patients assigned to the adverse-risk group were reclassified. Both, remission rates as well as 5-year EFS and 5-year OS rates differed statistically significantly when patients with secondary AML were allocated according to the ELN22 classification (supplemental Table 2; supplemental Figure 2A). Although the cohort of patients with ELN22 favorable-risk secondary AML was considered too small for further analysis, we again found significant differences in OS when assessing mutational subgroups within the ELN22 adverse-risk category, with an mOS of 10 months in patients with MR gene mutations vs 4 months in patients with TP53 mutations (supplemental Figure 2B). The 5-year OS rates for patients in the ELN22 favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk categories were 49%, 28%, and 8%, whereas the corresponding 5-year OS rates in patients classified according ELN17 were 46%, 15%, and 12%, respectively. However, within the subgroup of patients with secondary AML, reclassification according to ELN22 did not improve prognostic discrimination as per time-dependent ROC analysis (supplemental Figure 2C).

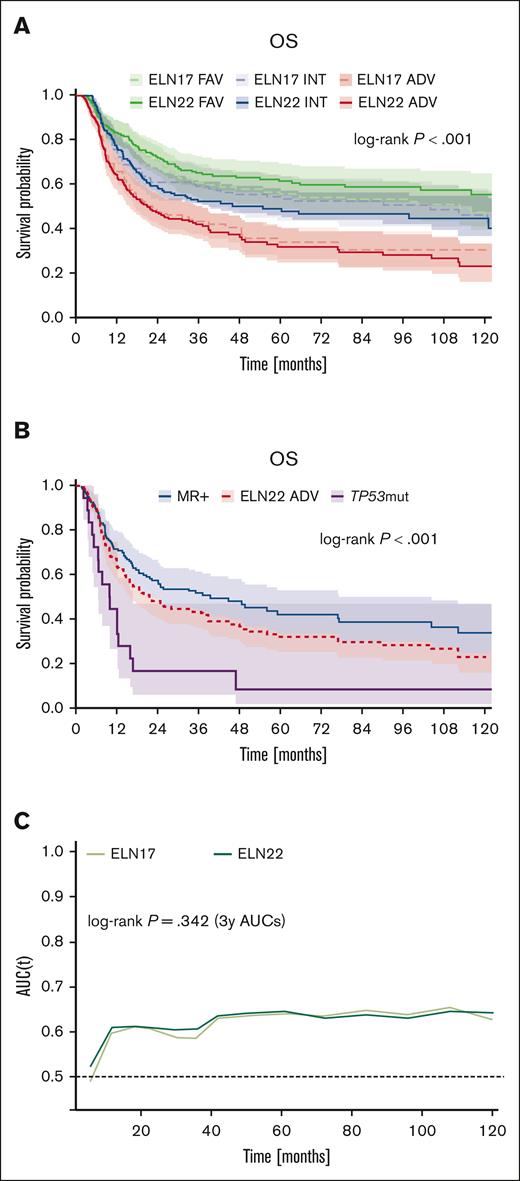

Prognostic impact of the ELN22 risk classification in patients undergoing alloHCT

In our cohort, 504 patients (median age, 48 years; range, 18-75) underwent alloHCT, of whom 238 patients received alloHCT in first CR. Donors were sibling donors and matched unrelated donors in 43% and 57%, respectively. ELN22 risk at diagnosis was favorable, intermediate, and adverse risk in 179 (36%), 151 (30%), and 174 patients (34%), respectively. Compared with the ELN17 risk stratification, 16% of patients previously assigned to the favorable-risk category, 53% of patients classified as intermediate risk, and 14% of patients assigned to the adverse-risk group were reclassified (supplemental Table 3). After a median follow-up of 76 months, the allocation of patients who underwent alloHCT according to the ELN22 risk categories resulted in a statistically significantly distinct EFS and OS but not RFS. The 5-year EFS rates for patients in the favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk categories were 36%, 28%, and 19%, 5-year RFS rates were 40%, 37%, and 35%; and 5-year OS rates were 61%, 49%, and 21%, respectively (Figure 7A). Again, we observed significant differences in OS when assessing ELN22 adverse-risk molecular subgroups separately (mOS, 40 months vs 10 months; corresponding 5-year OS rate, 42% vs 8% in patients with MR gene mutations [ie, mutations in ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2] and patients with TP53 mutations, respectively; P < .001; Figure 7B). However, no differences in OS within the ELN22 favorable-risk group (patients with CBF-AML vs CEBPA bZIP in-frame mutations vs NPM1 mutations) were observed (P = .95). The 5-year OS rates for patients in the ELN22 favorable-, ELN22 intermediate-, and ELN22 adverse-risk categories were 61%, 49%, and 21%, whereas the corresponding 5-year OS rates in patients classified according ELN17 were 56%, 54%, and 19%, respectively. Nonetheless, in contrast to the overall cohort, reclassification according to the ELN22 recommendations did not result in an improved prognostic discrimination for OS, as evaluated by time-dependent ROC curves (Figure 7C).

Risk stratification and outcome in patients who underwent alloHCT (n = 504). (A) Comparison of outcome in patients stratified according to either ELN17 or ELN22. (B) Outcome of patients with MR gene mutations compared with patients with TP53 mutations within the ELN22 adverse-risk category. (C) Comparison of prognostic discrimination as assessed by time-dependent ROC curves for OS between ELN17 and ELN22.

Risk stratification and outcome in patients who underwent alloHCT (n = 504). (A) Comparison of outcome in patients stratified according to either ELN17 or ELN22. (B) Outcome of patients with MR gene mutations compared with patients with TP53 mutations within the ELN22 adverse-risk category. (C) Comparison of prognostic discrimination as assessed by time-dependent ROC curves for OS between ELN17 and ELN22.

Discussion

Here, we evaluated the ELN22 risk stratification in a large cohort of intensively treated patients with AML and compared the performance of the modified classification with the previous ELN17 risk classification.

The ELN22 risk assessment led to a revised classification in 22% of patients. Most patients were reclassified into ELN22 intermediate- or adverse-risk groups, either due to the presence of FLT3-ITD or newly added MR gene alterations, respectively. These findings are in line with previous reports, for example, Lachowiez et al reported reclassification in 15% of patients, predominantly affecting those with FLT3-ITD or MR gene mutations.8,9,11

Regarding patient outcomes, we could also show that the allocation of patients according to the ELN22 risk categories resulted in a significantly distinct EFS, RFS, and OS. Furthermore, the revised risk stratification maintained its prognostic value when focusing on patients aged >60 years. Here, our data are comparable with results reported by Rausch et al, who found the revised ELN classification to perform well for RFS and OS, irrespective of age.11 Similarly, while evaluating 1637 patients with AML treated mainly on CALBG trials, Mrózek et al reported that the ELN22 classification is predictive for CR, disease-free survival and OS. However, they could not show significant differences in OS between the intermediate- and adverse-risk groups in older adults.9

Based on recent reports, the revised ELN classification substituted biallelic CEBPA mutations with in-frame mutations affecting the bZIP domain of the CEBPA gene as a criterion for allocating patients as ELN22 favorable risk.25 Our data, in line with other reports, confirmed that harboring CEBPA bZIP in-frame mutations confers a favorable outcome, comparable with those in patients with CBF AML. Regarding patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML with or without MR gene comutations, we did not observe significant differences in CR rates or OS, even when stratifying for age or MR gene mutation VAF or when focusing on NPM1-mutated patients. Accordingly, additional MR gene mutations seem not to abrogate the positive prognostic value of co-occurring ELN22 favorable-risk alterations. In contrast, Mrózek et al found that MR gene mutations significantly affect outcome in patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML, especially those with NPM1-mutated/FLT3 wild-type disease.9 Similarly, Lachowiez et al found inferior OS in in ELN22 favorable-risk NPM1-mutated patients with MR gene mutations, especially in patients aged <60 years.27 However, our results are in line with a previous report not observing significant differences in CR rates or OS between NPM1-mutated patients with or without additional MR gene mutations.28

Another major change in the revised ELN classification is the implementation of additional MR gene mutations as an adverse-risk marker, unless they co-occur with favorable-risk alterations. In our cohort, 112 patients (7% of the entire population) were reallocated to the adverse-risk group due to the presence of newly added MR gene mutations. The outcome in patients harboring these MR gene mutations was superior compared with other adverse-risk patients, such as patients with ASXL1 and/or RUNX1 mutations or patients with TP53 abnormalities. Of note, the 5-year OS rate in MR gene–mutated patients was even comparable with those with ELN22 intermediate-risk AML. Here, we observed a wide range in terms of OS when evaluating patients with MR gene mutations in detail. Although patients with evidence of mutations in EZH2, STAG2, or ZRSR2 mutations showed an intermediate-like 5-year OS, the OS in patients with U2AF1 mutations was comparable with those with TP53 alterations (5%). Again, our findings are supported by previous reports. Rausch et al found that patients with MR gene mutations had significantly better RFS and OS than other adverse-risk patients and did not show a significant difference in RFS compared with the intermediate-risk cohort; conclusively, they argue for classifying MR gene mutations patients as intermediate risk.11 Similarly, Mrózek et al found that OS in patients with MR gene mutations was significantly better than in other adverse-risk patients, which was particularly true for patients with co-occurring favorable-risk alterations.9 Based on previous published reports suggesting that the negative prognostic effect of MR gene mutations might be associated with higher VAF rather than binary presence or absence of MR gene mutations, we also assessed the value of MR gene VAFs in our cohort.29,30 When applying a cutoff of less than or equal to/greater than median VAF, we indeed observed a trend for worse OS in patients with MR gene mutations with higher VAF. Accordingly, we recommend additional analysis to determine the optimal VAF cutoffs and to evaluate when the binary presence or absence or MR gene alteration VAF is more important for the prognostic value of the variable, not only in patients within the ELN22 adverse-risk category but also in patients with ELN22 favorable-risk AML with MR gene comutations.

Based on time-dependent ROC curves, we could show that the reclassification according to the ELN22 recommendations resulted in an improved prognostic discrimination for OS. Our results are supported by a previous study by Lachowiez et al.8 In contrast, despite the newly introduced changes, others could not show any significant advantage of the revised ELN classification with respect to prediction ability so far.9,11 One study evaluating the performance of the ELN classification in the setting of alloHCT even favored the ELN17 stratification.16

Additionally, we evaluated the prognostic value of the ELN22 classification in patients with AML secondary to antecedent MDS or MDS/MPN. Naturally, this cohort was enriched for MR gene mutations, leading to allocation to the ELN22 adverse-risk category in the majority of patients. However, comparable with the entire cohort, remission rates as well as 5-year EFS and 5-year OS rates differed significantly when patients with secondary AML were stratified according to the ELN22 classification. Accordingly, in line with previous reports, ELN classification seems a valuable tool for outcome prognostication, not only in de novo AML but also in patients with secondary AML.31

Comparable with the entire cohort, the allocation of patients who underwent alloHCT according to the ELN22 risk categories resulted in significantly distinct EFS and OS. However, in these patients, the ELN22 risk stratification did not significantly improve predictive significance compared with ELN17. These findings are in line with a previous report by Jentzsch et al, in which ELN22 risk was associated with EFS, cumulative incidence of relapse, and OS, but reclassification did not improve outcome prognostication.16 Similarly, Jiménez-Vicente et al confirmed the prognostic value of ELN22 in patients undergoing alloHCT, including those who received transplant in first CR.15

So far, several manuscripts evaluating the revised ELN risk classification have been published. Some of these studies report data on relatively small patient cohorts, whereas others evaluated patients treated heterogeneously with either different protocols of IC, low-dose chemotherapy, HMAs, venetoclax, or investigational products. In contrast, the major strength of our study is the large cohort of patients investigated, who were treated with cytarabine plus anthracycline/mitoxantrone–based IC across all ages. Moreover, many patients assigned to the intermediate- or adverse-risk categories received alloHCT in first CR, representing the current standard of care. Additionally, our analysis also includes patients with secondary and therapy-related AML, whereas others only focused on patients with de novo AML.9,10 However, we acknowledge that the retrospective character is a limitation of our study. Additionally, patient numbers in rare genetic subgroups such as the KAT6A::CREBBP fusion or MECOM rearrangements were not sufficient for reliable evaluations.

In conclusion, our evaluation of the ELN22 risk stratification, which is based on 1 of the largest cohorts of intensively treated patients published so far, confirms its value in AML prognostication. The revised ELN22 classification is of predictive significance in intensively treated patients with AML, irrespective of age, AML ontogeny, and postremission treatment, and improves prognostic discrimination compared with the former ELN17 stratification. Given the heterogeneous outcome of patients with MR gene mutations, ranging from those with ELN22 intermediate risk to those with ELN22 adverse risk, we argue for reevaluating the prognostic value of each mutation in larger data sets to further refine the genetic risk stratification in AML, not only within the ELN22 adverse-risk group but also when co-occurring with ELN22 favorable-risk alterations.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients who consented to participate in the aforementioned clinical trials/registries and the families who supported them.

The authors deeply regret the tragic death of our highly esteemed co-author Götz Ulrich Grigoleit.

Authorship

Contribution: J.-N.E., S.S., and C.T. were responsible for data collection; L.R., M. Bill, and S.Z. performed data analyses; L.R., M. Bill, and C.R. drafted the manuscript; and all authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Götz Ulrich Grigoleit died on 30 July 2024.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Leo Ruhnke, Department of Internal Medicine I, University Hospital Dresden, Technical University Dresden, Fetscherstraße 74, 01309 Dresden, Germany; email: leo.ruhnke@ukdd.de.

References

Author notes

L.R., M.B., C.T., and C.R. contributed equally to this study.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Leo Ruhnke (leo.ruhnke@ukdd.de).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.