Key Points

In a case-control study, TP53/KRAS variants were enriched in relapsing patients at initial diagnosis compared with nonrelapsing patients.

In unselected patients, TP53/KRAS variants combined with poor treatment response identified a subgroup with an ultrahigh risk of T-ALL.

Visual Abstract

Variations in the TP53 and KRAS genes indicate a particularly adverse prognosis in relapsed pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). We hypothesized that these variations might be subclonally present at disease onset and contribute to relapse risk. To test this, we examined 2 cohorts of children diagnosed with T-ALL: cohort 1 with 81 patients who relapsed and 79 who matched nonrelapsing controls, and cohort 2 with 226 consecutive patients, 30 of whom relapsed. In cohort 1, targeted sequencing revealed TP53 clonal and subclonal variants in 6 of 81 relapsing patients but none in the nonrelapsing group (P = .014). KRAS alterations were found in 9 of 81 relapsing patients compared with 2 of 79 nonrelapsing patients (P = .032). Survival analysis showed that none of the relapsed patients with TP53 and/or KRAS alterations survived, whereas 19 of 67 relapsed patients without such variants did, with a minimum follow-up time of 3 years (P = .023). In cohort 2, none of the relapsing patients but 10 of 196 nonrelapsing patients carried TP53 or KRAS variants, indicating that mutation status alone does not predict poor prognosis. All 10 nonrelapsing patients with mutations had a favorable early treatment response. Among the total cohort of 386 patients, 188 showed poor treatment response, of whom 69 relapsed. Of these poor responders, 9 harbored TP53 or KRAS variants. In conclusion, subclonal TP53 and KRAS alterations identified at the time of initial diagnosis, along with a poor treatment response, characterize a subset of children with T-ALL who face a dismal prognosis and who may benefit from alternative treatment approaches.

Introduction

Relapse is the main cause of death from pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), an aggressive hematologic malignancy that accounts for ∼15% of pediatric ALL.1 Long-term survival rates in children with T-ALL exceed 80% with intensive chemotherapy.2,3 However, those patients who suffer relapse face a dismal prognosis.

Genetic and epigenetic evolution are known mechanisms driving treatment resistance and relapse in many malignancies.4,5 Recently, a comprehensive genomic analysis of a large number of children and young adults with T-ALL enrolled on the international Children's Oncology Group (COG) AAL0434 study demonstrated several previously unknown clonal drivers of T-ALL, some of which with prognostic significance and some even overriding the prognostic information provided by minimal residual disease (MRD) analyses.6 It is also known that in T-ALL, the number of somatic variants increases during the transition from initial disease to relapse7 and that a number of alterations are associated with a fatal course at the time of relapse. Specifically, variants with a particularly negative effect on prognosis at the time of relapse affect TP53, KRAS, MSH6, USP7, IL7R, CNOT3, and NRAS genes, which collectively identify ∼50% of patients who will succumb to relapse.8,9 Variants of other genes were found to be enriched in T-ALL relapse and, in some cases, potentially contributing to treatment resistance.7,8,10,11

Relapse-specific variants can frequently be tracked back to the initial leukemia by deep sequencing.7 Here, we have tested the hypothesis that variants associated with a fatal course when present at the time of relapse can predict the risk of relapse when detected in a subclone of the T-ALL at first diagnosis. As has been observed in solid tumors and acute myelogenous leukemia, such subclonal variants may putatively be selected for during treatment, drive the evolution of relapse, and serve as prognostic biomarkers as early as at the time of initial diagnosis.12-14

Methods

Patient characteristics

All samples were collected from children and adolescents (aged <18 years) at the time of initial diagnosis of a T-ALL. The patients were treated on ALL- Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM) protocols (ALL-BFM 1995, n = 19; ALL-BFM 2000, n = 179; Associazione Italiana Ematologia Oncologia Pediatrica Italian (AIEOP)-BFM ALL 2009, n = 137; and AIEOP-BFM ALL 2017, n = 51). These studies were approved by the ethics committee of Hannover Medical School (ALL-BFM 1995 and 2000) and the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel (AIEOP-BFM ALL 2009 and 2017). The risk stratification of the BFM series of pediatric T-ALL trials is based on the number of peripheral blasts on day 8 of treatment with prednisolone and an initial dose of intrathecal methotrexate (prednisone response) and, since the BFM-2000 study, additionally on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–MRD response after induction (day 33) and after consolidation (day 78).2

In cohort 1, samples of T-ALL initial diagnosis were selected based on a case-control design. First, all available samples from initial diagnosis of patients who later relapsed (n = 81) were analyzed. As a control, we selected samples of 79 patients who had remained in first complete remission for a follow-up time of at least 3 years, a period during which virtually all T-ALL relapses are known to occur.15 The control group was matched to the group of relapsing patients according to the following criteria with decreasing priority: treatment group (standard risk, medium risk, and high risk [HR]), MRD after induction and consolidation (MRD day 78; low level: <10−3 leukemic cells, high level: ≥10−3 leukemic cells in the bone marrow aspirate2), prednisone response (good, blast count on day 8 of <1/nL; poor, ≥1/nL), initial blast count (≥100/nL, <100/nL), sex (male, n = 119; female, n = 41), and age (1-17.9 years; Tables 1 and 2).

Clinical characteristics of cohorts 1 and 2

| Parameter . | Variable . | Total . | Cohort 1 . | P value . | Total . | Cohort 2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse . | CCR . | Relapse . | CCR . | |||||

| N (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | N (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | |||

| Total | 160 | 81 | 79 | 226 | 30 (13.3) | 196 (86.7) | ||

| BFM study protocol | 1995 | 19 (11.9) | 11 (13.6) | 8 (10.1) | .80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2000 | 99 (61.9) | 49 (60.5) | 50 (63.3) | 80 (35.4) | 7 (23.3) | 73 (37.2) | ||

| 2009 | 42 (26.3) | 21 (25.9) | 21 (26.6) | 95 (42) | 15 (50) | 80 (40.8) | ||

| 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51 (22.6) | 8 (26.7) | 43 (21.9) | ||

| Sex | Male | 119 (74.4) | 59 (72.8) | 60 (75.9) | .65 | 166 (73.8) | 22 (73.3) | 144 (73.8) |

| Female | 41 (25.6) | 22 (27.2) | 19 (24.1) | 59 (26.2) | 8 (26.7) | 51 (26.2) | ||

| No data | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Risk stratification | SR | 4 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | .9 | 30 (13.3) | 1 (3.3) | 29 (14.9) |

| MR | 60 (37.5) | 29 (35.8) | 31 (39.2) | 103 (45.8) | 10 (33.3) | 93 (47.7) | ||

| HR | 96 (60) | 50 (61.7) | 46 (58.2) | 92 (40.9) | 19 (63.3) | 73 (37.4) | ||

| No data | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Age at initial diagnosis | Median age (min-max), y | 9.9 (1.0-17.9) | 9.2 (1.0-17.9) | 9.4 (1.2-17.8) | .62 | |||

| No data | 226 | 30 | 196 | |||||

| Prednisone response | Good | 75 (47.8) | 35 (44.9) | 39 (46.8) | .57 | 143 (65.6) | 15 (50) | 128 (68.1) |

| Poor | 83 (52.9) | 43 (55.1) | 40 (50.6) | 75 (34.4) | 15 (50) | 60 (31.9) | ||

| No data | 3 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | ||

| MRD1 (day 33)∗ | Low (<10−3) | 48 (36.6) | 19 (29.7) | 29 (43.3) | .11 | 107 (51.7) | 9 (34.6) | 88 (51.8) |

| High (≥10−3) | 83 (63.4) | 45 (70.3) | 38 (56.7) | 100 (48.3) | 17 (65.4) | 82 (48.2) | ||

| No data | 29 | 17 | 12 | 19 | 4 | 26 | ||

| MRD2 (day 78)∗ | Low (<10−3) | 95 (72) | 44 (67.7) | 51 (76.1) | .28 | 138 (69.3) | 15 (57.7) | 112 (69.1) |

| High (≥10−3) | 37 (28) | 21 (32.3) | 16 (23.9) | 61 (30.7) | 11 (42.3) | 50 (30.9) | ||

| No data | 28 | 16 | 12 | 27 | 4 | 34 | ||

| Stem cell transplantation in first remission | Yes | 33 (20.6) | 15 (18.5) | 18 (22.8) | .51 | 39 (17.3) | 15 (50) | 24 (12.2) |

| No | 127 (79.4) | 66 (81.5) | 61 (77.2) | 187 (82.7) | 15 (50) | 172 (87.8) | ||

| Time to relapse | Median time (min-max), y | 1.6 (0.17-7.08) | — | — | — | |||

| No data | 21 | 30 | ||||||

| Parameter . | Variable . | Total . | Cohort 1 . | P value . | Total . | Cohort 2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse . | CCR . | Relapse . | CCR . | |||||

| N (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | N (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | |||

| Total | 160 | 81 | 79 | 226 | 30 (13.3) | 196 (86.7) | ||

| BFM study protocol | 1995 | 19 (11.9) | 11 (13.6) | 8 (10.1) | .80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2000 | 99 (61.9) | 49 (60.5) | 50 (63.3) | 80 (35.4) | 7 (23.3) | 73 (37.2) | ||

| 2009 | 42 (26.3) | 21 (25.9) | 21 (26.6) | 95 (42) | 15 (50) | 80 (40.8) | ||

| 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51 (22.6) | 8 (26.7) | 43 (21.9) | ||

| Sex | Male | 119 (74.4) | 59 (72.8) | 60 (75.9) | .65 | 166 (73.8) | 22 (73.3) | 144 (73.8) |

| Female | 41 (25.6) | 22 (27.2) | 19 (24.1) | 59 (26.2) | 8 (26.7) | 51 (26.2) | ||

| No data | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Risk stratification | SR | 4 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | .9 | 30 (13.3) | 1 (3.3) | 29 (14.9) |

| MR | 60 (37.5) | 29 (35.8) | 31 (39.2) | 103 (45.8) | 10 (33.3) | 93 (47.7) | ||

| HR | 96 (60) | 50 (61.7) | 46 (58.2) | 92 (40.9) | 19 (63.3) | 73 (37.4) | ||

| No data | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Age at initial diagnosis | Median age (min-max), y | 9.9 (1.0-17.9) | 9.2 (1.0-17.9) | 9.4 (1.2-17.8) | .62 | |||

| No data | 226 | 30 | 196 | |||||

| Prednisone response | Good | 75 (47.8) | 35 (44.9) | 39 (46.8) | .57 | 143 (65.6) | 15 (50) | 128 (68.1) |

| Poor | 83 (52.9) | 43 (55.1) | 40 (50.6) | 75 (34.4) | 15 (50) | 60 (31.9) | ||

| No data | 3 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | ||

| MRD1 (day 33)∗ | Low (<10−3) | 48 (36.6) | 19 (29.7) | 29 (43.3) | .11 | 107 (51.7) | 9 (34.6) | 88 (51.8) |

| High (≥10−3) | 83 (63.4) | 45 (70.3) | 38 (56.7) | 100 (48.3) | 17 (65.4) | 82 (48.2) | ||

| No data | 29 | 17 | 12 | 19 | 4 | 26 | ||

| MRD2 (day 78)∗ | Low (<10−3) | 95 (72) | 44 (67.7) | 51 (76.1) | .28 | 138 (69.3) | 15 (57.7) | 112 (69.1) |

| High (≥10−3) | 37 (28) | 21 (32.3) | 16 (23.9) | 61 (30.7) | 11 (42.3) | 50 (30.9) | ||

| No data | 28 | 16 | 12 | 27 | 4 | 34 | ||

| Stem cell transplantation in first remission | Yes | 33 (20.6) | 15 (18.5) | 18 (22.8) | .51 | 39 (17.3) | 15 (50) | 24 (12.2) |

| No | 127 (79.4) | 66 (81.5) | 61 (77.2) | 187 (82.7) | 15 (50) | 172 (87.8) | ||

| Time to relapse | Median time (min-max), y | 1.6 (0.17-7.08) | — | — | — | |||

| No data | 21 | 30 | ||||||

Patients of cohort 1 (n = 160) are classified into 2 different groups according to their outcome: patients with relapse (n = 81) and patients who have remained in continuous complete remissions for >3 years (n = 79). The 2 groups were matched according to the parameters shown, which were equally distributed between both groups. P values were either assessed by χ2 test for categorical variables or by Mann-Whitney U test for the continuous variable “age.” Statistical significance was defined as P < .05. P values were not adjusted for multiple testing because of the hypothesis-generating concept of our study. Patients of cohort 2 were a randomly selected group of 226 patients with T-ALL at initial diagnosis who were treated on ALL-BFM protocols. Of these, 30 patients later relapsed whereas 196 patients had remained in continuous complete remission for >3 years. The clinical characteristics “age at initial diagnosis” and “time to relapse” were not available for these patients.

CCR, continuous complete remissions; max, maximum; min, minimum; MR, medium risk; MRD1/2, minimal residual disease; SR, standard risk.

MRD measured at day 33 and day 78 of induction therapy: low level, <10−3 leukemic cells; high level, ≥10−3 leukemic cells in bone marrow aspirates.

Clinical parameters and mutational status of cohort 1

| Clinical parameters . | Variable . | Total . | TP53 variant . | KRAS variant . | KRAS and TP53 variant . | No TP53 variant . | No KRAS variant . | P value∗ . | P value† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Total | 160 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 154 | 149 | |||

| Sex | Male | 119 (74.4) | 4 (80) | 7 (70) | 1 (100) | 114 (74) | 111 (74.5) | .608 | .897 |

| Female | 41 (25.6) | 1 (20) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 40 (26) | 38 (25.5) | |||

| Age at initial diagnosis | Median age (min-max), y | 9.9 (1.0-17.9) | 13.4 (10.2-16.9) | 10.5 (4-16.1) | 13.6 (13.6) | 9.2 (1.0-17.9) | 9.1 (1-17.9) | .031 | .285 |

| Prednisone response | Good | 75 (47.8) | 3 (75) | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) | 71 (46.7) | 70 (47.6) | .558 | .640 |

| Poor | 83 (52.9) | 1 (25) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (100) | 81 (53.3) | 77 (52.4) | |||

| No data | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |||

| MRD1 (day 33)‡ | Low (<10−3) | 48 (36.6) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 46 (36.2) | 48 (39.3) | .573 | .018 |

| High (≥10−3) | 83 (63.4) | 1 (33.3) | 8 (100) | 1 (100) | 81 (63.8) | 74 (60.7) | |||

| No data | 29 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 27 | 27 | |||

| MRD2 (day 78)‡ | Low (<10−3) | 95 (72) | 2 (66.7) | 6 (85.7) | 0 (0) | 93 (72.7) | 89 (71.8) | .320 | .844 |

| High (≥10−3) | 37 (28) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (100) | 35 (27.3) | 35 (28.2) | |||

| No data | 28 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 26 | 25 | |||

| Risk stratification | SR | 4 (2.5) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.7) | .077 | .850 |

| MR | 60 (37.5) | 2 (40) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 58 (37.7) | 56 (37.6) | |||

| HR | 96 (60) | 2 (40) | 6 (60) | 1 (100) | 93 (60.4) | 89 (59.7) | |||

| First-line treatment | SCT | 33 (20.6) | 1 (20) | 2 (20) | 1 (100) | 31 (20.1) | 30 (20.1) | .482 | .852 |

| HR without SCT | 63 (39.4) | 1 (20) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 62 (40.3) | 59 (39.6) | |||

| non-HR | 64 (40) | 3 (60) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 61 (39.6) | 60 (40.3) |

| Clinical parameters . | Variable . | Total . | TP53 variant . | KRAS variant . | KRAS and TP53 variant . | No TP53 variant . | No KRAS variant . | P value∗ . | P value† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Total | 160 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 154 | 149 | |||

| Sex | Male | 119 (74.4) | 4 (80) | 7 (70) | 1 (100) | 114 (74) | 111 (74.5) | .608 | .897 |

| Female | 41 (25.6) | 1 (20) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 40 (26) | 38 (25.5) | |||

| Age at initial diagnosis | Median age (min-max), y | 9.9 (1.0-17.9) | 13.4 (10.2-16.9) | 10.5 (4-16.1) | 13.6 (13.6) | 9.2 (1.0-17.9) | 9.1 (1-17.9) | .031 | .285 |

| Prednisone response | Good | 75 (47.8) | 3 (75) | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0) | 71 (46.7) | 70 (47.6) | .558 | .640 |

| Poor | 83 (52.9) | 1 (25) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (100) | 81 (53.3) | 77 (52.4) | |||

| No data | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |||

| MRD1 (day 33)‡ | Low (<10−3) | 48 (36.6) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 46 (36.2) | 48 (39.3) | .573 | .018 |

| High (≥10−3) | 83 (63.4) | 1 (33.3) | 8 (100) | 1 (100) | 81 (63.8) | 74 (60.7) | |||

| No data | 29 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 27 | 27 | |||

| MRD2 (day 78)‡ | Low (<10−3) | 95 (72) | 2 (66.7) | 6 (85.7) | 0 (0) | 93 (72.7) | 89 (71.8) | .320 | .844 |

| High (≥10−3) | 37 (28) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (100) | 35 (27.3) | 35 (28.2) | |||

| No data | 28 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 26 | 25 | |||

| Risk stratification | SR | 4 (2.5) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.7) | .077 | .850 |

| MR | 60 (37.5) | 2 (40) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 58 (37.7) | 56 (37.6) | |||

| HR | 96 (60) | 2 (40) | 6 (60) | 1 (100) | 93 (60.4) | 89 (59.7) | |||

| First-line treatment | SCT | 33 (20.6) | 1 (20) | 2 (20) | 1 (100) | 31 (20.1) | 30 (20.1) | .482 | .852 |

| HR without SCT | 63 (39.4) | 1 (20) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 62 (40.3) | 59 (39.6) | |||

| non-HR | 64 (40) | 3 (60) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 61 (39.6) | 60 (40.3) |

Analysis of 160 samples of pediatric patients with T-ALL who were treated on ALL-BFM protocols (ALL-BFM 1995, n = 19; ALL-BFM 2000, n = 99; and AIEOP-BFM ALL 2009, n = 42). Samples of initial diagnosis of T-ALL were chosen based on a case-control-design; 81 samples were obtained from patients who later relapsed and 79 from patients who remained in first complete remission for at least 3 years. Patients in CCR were matched to relapsing patients with decreasing priority according to treatment group, MRD after induction and consolidation, prednisone response, blast cell count, sex, and age. Differences in outcome and clinical parameters between different variant groups were assessed by χ2 test for categorical variables and by Mann-Whitney U test for the continuous variable “age.” Statistical significance was defined as P < .05. P values were not adjusted for multiple testing due to the hypothesis-generating concept of our study.

CCR, continuous complete remissions; HR, high risk; max, maximum; min, minimum; MR, medium risk; MRD1/2, minimal residual disease; SCT, stem cell transplantation; SR, standard risk.

P value calculated between all patients with TP53 variants and all patients without TP53 variant.

P value calculated between all patients with KRAS variants and all patients without variants of this gene.

MRD measured at day 33 and day 78 of induction therapy: low level, <10−3 leukemic cells; high level, ≥10−3 leukemic cells in bone marrow aspirate.

In cohort 2, samples of 226 unselected, consecutive patients with T-ALL treated on the aforementioned protocols and with a minimal follow-up of 3 years were analyzed. Patients were treated either in Germany (n = 146) or in Austria (n = 80). In contrast to the first cohort, the samples of these 226 patients were only selected on the basis of availability of a leukemia sample obtained at initial diagnosis. Patient clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Ultradeep targeted sequencing

We performed targeted deep sequencing using a HaloPlex High Sensitivity (HS) target enrichment kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) for library preparation. The customized sequencing panel with 9 ultra-HR genes that were selected based on previous studies,7,8,10 confirming either prognostic relevance or enrichment in relapse, comprised a total of 137 target regions (supplemental Table 1). Altogether, 23 627 base pairs (bps) of all coding exons of the 9 genes were covered by 1910 amplicons. The DNA input for library preparation was quantified using Qubit double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) Broad Range (BR) assay kit (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) and depended on DNA quality, which was measured on the Agilent TapeStation (DIN [DNA integrity number] of ≥8, 50 ng; DIN of 7-4, 100 ng; and DIN of ≤3, 200 ng). Five library pools of 66, 78, 79, 81, and 82 samples of initial diagnosis were prepared according to Agilent's HaloPlex HS target enrichment protocol version C, 1 December 2016. Each library was sequenced as 75-bp paired reads either on 2 lanes using an Illumina NextSeq 500 HIGH 150 cycles instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA; for the first cohort of samples) or on 3 lanes using an Illumina NextSeq 2000 HIGH instrument (Illumina; for the second cohort of samples) with identical sequencing settings. The use of unique molecular identifiers that label each DNA copy and mitigate amplification artefacts was designed for very-deep sequencing (average read depth, 1012 ± 642 and 723 ± 491 unique reads, respectively). The threshold of detection was determined by coverage and set at a minimum allele frequency (AF) of 0.1% by the filtering criteria (see the following section).16,17 Although the identification of subclonal variants with a sensitivity of 0.1% goes beyond the sensitivity of conventional sequencing protocols, a more sensitive identification of subclonal mutations is challenging to quantify by this technology. As another limitation of HaloPlex sequencing, structural variants such as deletions of TP53 cannot be identified.

Analysis of the targeted deep sequencing data

The sequencing data were analyzed by the Agilent SureCall SNPPET Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) caller. In order to optimize the detection of low-frequency variants and at the same time minimize false-positive variants the SureCall SNPPET SNP caller was configured using the following stringent settings: variant score threshold at 0.3, minimum quality for base at 30, variant call quality threshold at 100, minimum variant AF (VAF) of 0.001, minimum number of reads supporting variant allele at 3, and minimum number of read pairs per barcode at 2. Variants were considered relevant if the population AF was <1% and if the variant was classified as pathogenic or likely-pathogenic by ClinVar or predicted to be deleterious by Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT),18 respectively. Thus, all variants included in our analysis have reported functionally damaging effects. The VAFs of these ranged between 19 and 2257 (0.84%), and 400 and 482 (83%).

Whole-exome sequencing of relapsed samples

Whole-exome sequencing of all available samples obtained at relapse of patients with subclonal TP53 variants at initial diagnosis was performed as previously described.19 Library preparation was performed using SureSelectXT Target Enrichment System for Illumina paired-end multiplexed sequencing library version 6 (Agilent) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The library was sequenced as 75-bp paired reads using Illumina NextSeq 500 deep-sequencing instrument (Illumina). The mean coverage of TP53 varied between 371 and 479.

Sanger sequencing of remission and relapse samples

To discriminate somatic from constitutional variants, we analyzed the positions of variants identified at initial diagnosis in the corresponding remission samples by Sanger sequencing. Of cohort 1, 25 DNA samples obtained at the time of first remission were available and amplified by PCR. Furthermore, we checked the presence of KRAS variants at relapse in 5 of 9 available corresponding relapse samples of patients of cohort 1 carrying KRAS variants at initial diagnosis by Sanger sequencing. Primers were designed to amplify a fragment of ∼400 bp that carried the patient-specific variant detected at initial diagnosis (supplemental Table 2). PCR products were purified by NucleoSpin gel and PCR clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Sanger sequencing was performed by Microsynth Seqlab in Göttingen, Germany. The sequencing data were analyzed by the Mutation Surveyor software version 5.0.0 (Softgenetics, State College, PA) with the human genome version hg18 as reference.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using the SPSS statistic software version 25.0.0. Differences in the distribution of parameters among patient subgroups were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorized variables. A P value of <.05 was defined as statistically significant. P values were not adjusted for multiple testing because of the hypothesis-generating concept of our study. Survival rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, differences were compared with the 2-sided log-rank test.

Results

Analysis of 81 relapsing and 79 nonrelapsing T-ALL samples obtained at initial diagnosis

When analyzing the frequencies of our 9 target genes, we found that subclonal TP53 variants occurred exclusively in patients later developing a relapse (Tables 3-5). Notably, 6 of 81 (patients 9, 41, 95, 110, 126, and 153) patients who later relapsed carried 7 different variants in TP53. In 1 patient (patient 95), we identified 2 variants (R196X and R282W) in the T-ALL cells (Table 3; supplemental Table 3A). Large deletions of TP53, which account for 5% of all TP53 variants could not be detected by the sequencing method used here, which was primarily designed to detect subclonal variants.20 AFs and the analyses of constitutional DNA obtained at the time of remission show that 6 of these 7 variants are somatic (AF, 4.4%-37.7%). One patient (patient 126) carried a TP53 variant at codon 248 (R248W), which is known to cause Li-Fraumeni syndrome21 with an AF of 49.4% in addition to a likely somatic variant in USP7 (AF, 28.2%), suggesting a constitutional variant in TP53 (Table 3; supplemental Table 3A). DNA obtained at the time of remission of this patient was not available.

AFs of TP53 variants identified at initial diagnosis of patients with T-ALL and in corresponding relapse samples

| Patient number . | TP53 variant . | TP53 AF . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial diagnosis, % . | Relapse, % . | ||

| 9 | A159D | 5.4 | 42 Infiltrated LN sample |

| 41 | R248Q | 5.7 | n.a.∗ |

| 110 | R248W | 24.9 | n.a. |

| 95 | R196X | 26.6 | 6† |

| R282W | 37.7 | 9† | |

| 126 | R248W | 49.4 | n.a. |

| 153 | R248Q | 4.4 | 3/6‡ BM/PB at the time of relapse with 95% blasts in BM |

| Patient number . | TP53 variant . | TP53 AF . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial diagnosis, % . | Relapse, % . | ||

| 9 | A159D | 5.4 | 42 Infiltrated LN sample |

| 41 | R248Q | 5.7 | n.a.∗ |

| 110 | R248W | 24.9 | n.a. |

| 95 | R196X | 26.6 | 6† |

| R282W | 37.7 | 9† | |

| 126 | R248W | 49.4 | n.a. |

| 153 | R248Q | 4.4 | 3/6‡ BM/PB at the time of relapse with 95% blasts in BM |

A total of 7 TP53 variants were detected in 6 patients with T-ALL, who later relapsed.

BM, bone marrow; CNS, central nervous system; LN, lymph node; n.a., not available; PB, peripheral blood.

The BM sample that was free of blasts by cytomorphology obtained at the time of an isolated CNS relapse did not reveal the TP53 variant identified at the time of initial disease. CSF was not available.

This patient had a nodal relapse. Material from the LN was not available for analysis. The BM analyzed was collected 4 weeks after therapy of the relapse had been initiated. Although cytomorphology of the BM did not reveal any blasts, exome sequencing indicated the presence of leukemia by detecting the TP53 variants that had been present at initial diagnosis at an AF of 6% and 9%, respectively.

The BM and PB of this patient revealed similar AFs of the TP53 variant at initial disease and at relapse. This patient had acquired a clonal USP7 variant at relapse (see text).

Patient and mutational profile of patients with TP53/KRAS mutation of the HR (n = 9) group

| Patient number . | Sex . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Date of first diagnosis . | Risk group based on early treatment response . | Prednisone response . | MRD TP1 (day 33, after induction therapy) . | MRD TP2 (after consolidation therapy) . | Stem cell transplantation in first remission . | Time to relapse . | Gene . | AA change . | AF at initial diagnosis, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | Male | 16,9 | June 2001 | HR | Poor | 10−4 | Negative | No | 3 mo | TP53 | R248Q | 5.7 |

| 110 | Male | 13,6 | May 2004 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | 10−2 | Yes | 12 mo | TP53 | R248W | 24.9 |

| KRAS | T58I | 17.4 | ||||||||||

| 126 | Male | 10,2 | July 2003 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | 10−1 | Yes | 12 mo | TP53 | R248W | 49.4 |

| 47 | Male | 15,5 | July 2004 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | n.a. | No | 2 mo | KRAS | G13C | 3.7 |

| 33 | Female | 5,3 | July 2001 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | 10−2 | Yes | 10 mo | KRAS | G12D | 45.5 |

| 73 | Male | 5,1 | March 2009 | HR | Poor | 10−3 | 10−5 | No | 15 mo | KRAS | G12V | 36.4 |

| 77 | Female | 15,3 | February 2008 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | 10−4 | No | 38 mo | KRAS | Q22K | 4.7 |

| KRAS | 63_63del | 0.8 | ||||||||||

| 35 | Female | 4 | January 2015 | HR | n.a. | 10−3 | Positive, n.q. | No | 7 mo | KRAS | G12S | 30.1 |

| 48 | Male | 15,1 | November 2000 | HR | Poor | n.a. | n.a. | No | CCR | KRAS | A18D | 10.0 |

| Patient number . | Sex . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Date of first diagnosis . | Risk group based on early treatment response . | Prednisone response . | MRD TP1 (day 33, after induction therapy) . | MRD TP2 (after consolidation therapy) . | Stem cell transplantation in first remission . | Time to relapse . | Gene . | AA change . | AF at initial diagnosis, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | Male | 16,9 | June 2001 | HR | Poor | 10−4 | Negative | No | 3 mo | TP53 | R248Q | 5.7 |

| 110 | Male | 13,6 | May 2004 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | 10−2 | Yes | 12 mo | TP53 | R248W | 24.9 |

| KRAS | T58I | 17.4 | ||||||||||

| 126 | Male | 10,2 | July 2003 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | 10−1 | Yes | 12 mo | TP53 | R248W | 49.4 |

| 47 | Male | 15,5 | July 2004 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | n.a. | No | 2 mo | KRAS | G13C | 3.7 |

| 33 | Female | 5,3 | July 2001 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | 10−2 | Yes | 10 mo | KRAS | G12D | 45.5 |

| 73 | Male | 5,1 | March 2009 | HR | Poor | 10−3 | 10−5 | No | 15 mo | KRAS | G12V | 36.4 |

| 77 | Female | 15,3 | February 2008 | HR | Poor | 10−1 | 10−4 | No | 38 mo | KRAS | Q22K | 4.7 |

| KRAS | 63_63del | 0.8 | ||||||||||

| 35 | Female | 4 | January 2015 | HR | n.a. | 10−3 | Positive, n.q. | No | 7 mo | KRAS | G12S | 30.1 |

| 48 | Male | 15,1 | November 2000 | HR | Poor | n.a. | n.a. | No | CCR | KRAS | A18D | 10.0 |

We identified 9 of 386 patients with T-ALL (2.3%) with subclonal and clonal TP53/KRAS variants at initial diagnosis, who exhibited an unfavorable treatment response. Of 9 HR patients, 8 relapsed and died (patient number 41, 110, 126, 47, 33, 73, 77 and 35).

AA, amino acid; CCR, continuous complete remission; HR, high risk; n.a., not available; n.q., not quantifiable; TP, time point.

Patient and mutational profile of patients with TP53/KRAS mutation of the non-HR (standard and medium risk, n = 17) group

| Patient number . | Sex . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Date of first diagnosis . | Risk group based on early treatment response . | Prednisone response . | MRD TP1 (day 33, after induction therapy) . | MRD TP2 (after consolidation therapy) . | Stem cell transplantation in first remission . | Time to relapse . | Gene . | AA change . | AF at initial diagnosis, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 353 | Male | n.a. | July 2016 | MR | Good | Positive, n.q. | Negative | No | CCR | TP53 | F113L | 3.0 |

| 327 | Male | n.a. | August 2018 | MR | Good | Positive, n.q. | Negative | No | CCR | TP53 | R248W | 8.4 |

| 227 | Male | n.a. | December 2017 | MR | Good | 10−4 | Positive, n.q. | No | CCR | TP53 | R213X | 10.1 |

| 191 | Male | n.a. | April 2006 | MR | Good | 10−4 | 100 | No | CCR | KRAS | G12D | 11.3 |

| 289 | Female | n.a. | June 2016 | MR | Good | 10−3 | Positive, n.q. | No | CCR | KRAS | G13D | 12.9 |

| 215 | Male | n.a. | January 2016 | MR | Good | Negative | Positive, n.q. | No | CCR | TP53 | T253S | 13.6 |

| 166 | Male | n.a. | September 2009 | MR | Good | 10−1 | 10−4 | No | CCR | KRAS | G13C | 27.6 |

| 194 | Male | n.a. | November 2017 | MR | Good | n.a. | n.a. | No | CCR | KRAS | A146V | 34.7 |

| 187 | Male | n.a. | June 2019 | MR | Good | Positive, n.q. | Negative | No | CCR | KRAS | G12V | 40.6 |

| 386 | Male | n.a. | March 2008 | SR | good | Negative | Negative | No | CCR | TP53 | Y234C | 84.5 |

| 3 | Male | 16,1 | January 2006 | MR | good | 10−2 | 10−4 | No | 10 mo | KRAS | G12V | 40.2 |

| 75 | Male | 6,5 | July 2000 | MR | Good | 10−2 | 10−4 | No | 18 mo | KRAS | K117N | 7.6 |

| 120 | Male | 12,3 | October 2008 | MR | Good | n.a. | n.a. | No | 13 mo | KRAS | K117N | 17.2 |

| 20 | Male | 9,9 | November 2007 | MR | Good | 10−3 | 10−4 | No | CCR | KRAS | G12V | 36.7 |

| 95 | Male | 15,4 | November 2004 | MR | Good | n.a. | n.a. | No | 5 mo | TP53 | R282W | 37.7 |

| TP53 | R196X | 26.6 | ||||||||||

| 9 | Male | 13 | March 2000 | SR | Good | Negative | Negative | No | 14 mo | TP53 | A159D | 5.4 |

| 153 | Female | 11,3 | January 1997 | MR | Good | n.a. | n.a. | No | 4 mo | TP53 | R248Q | 4.4 |

| Patient number . | Sex . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Date of first diagnosis . | Risk group based on early treatment response . | Prednisone response . | MRD TP1 (day 33, after induction therapy) . | MRD TP2 (after consolidation therapy) . | Stem cell transplantation in first remission . | Time to relapse . | Gene . | AA change . | AF at initial diagnosis, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 353 | Male | n.a. | July 2016 | MR | Good | Positive, n.q. | Negative | No | CCR | TP53 | F113L | 3.0 |

| 327 | Male | n.a. | August 2018 | MR | Good | Positive, n.q. | Negative | No | CCR | TP53 | R248W | 8.4 |

| 227 | Male | n.a. | December 2017 | MR | Good | 10−4 | Positive, n.q. | No | CCR | TP53 | R213X | 10.1 |

| 191 | Male | n.a. | April 2006 | MR | Good | 10−4 | 100 | No | CCR | KRAS | G12D | 11.3 |

| 289 | Female | n.a. | June 2016 | MR | Good | 10−3 | Positive, n.q. | No | CCR | KRAS | G13D | 12.9 |

| 215 | Male | n.a. | January 2016 | MR | Good | Negative | Positive, n.q. | No | CCR | TP53 | T253S | 13.6 |

| 166 | Male | n.a. | September 2009 | MR | Good | 10−1 | 10−4 | No | CCR | KRAS | G13C | 27.6 |

| 194 | Male | n.a. | November 2017 | MR | Good | n.a. | n.a. | No | CCR | KRAS | A146V | 34.7 |

| 187 | Male | n.a. | June 2019 | MR | Good | Positive, n.q. | Negative | No | CCR | KRAS | G12V | 40.6 |

| 386 | Male | n.a. | March 2008 | SR | good | Negative | Negative | No | CCR | TP53 | Y234C | 84.5 |

| 3 | Male | 16,1 | January 2006 | MR | good | 10−2 | 10−4 | No | 10 mo | KRAS | G12V | 40.2 |

| 75 | Male | 6,5 | July 2000 | MR | Good | 10−2 | 10−4 | No | 18 mo | KRAS | K117N | 7.6 |

| 120 | Male | 12,3 | October 2008 | MR | Good | n.a. | n.a. | No | 13 mo | KRAS | K117N | 17.2 |

| 20 | Male | 9,9 | November 2007 | MR | Good | 10−3 | 10−4 | No | CCR | KRAS | G12V | 36.7 |

| 95 | Male | 15,4 | November 2004 | MR | Good | n.a. | n.a. | No | 5 mo | TP53 | R282W | 37.7 |

| TP53 | R196X | 26.6 | ||||||||||

| 9 | Male | 13 | March 2000 | SR | Good | Negative | Negative | No | 14 mo | TP53 | A159D | 5.4 |

| 153 | Female | 11,3 | January 1997 | MR | Good | n.a. | n.a. | No | 4 mo | TP53 | R248Q | 4.4 |

We identified 17 of 386 patients with T-ALL (4.4%) with subclonal and clonal TP53/KRAS variants at initial diagnosis, who exhibited a favorable treatment response. Of these 17 patients, 6 relapsed (light gray).

AA, amino acid; MR, medium risk; n.a., not available; n.q., not quantifiable; SR, standard risk; TP, time point.

Three of these 6 patients had been stratified into the HR arm of the treatment protocols. Two patients had received allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first remission, whereas a third patient did not receive stem cell transplantation because of a favorable MRD response. The other 3 patients were stratified to the intermediate risk groups based on treatment response and received neither HR chemotherapy nor an allotransplant. By contrast, in the 79 nonrelapsing matched control patients no TP53 variant was detected.

All TP53 variants, comprising 6 missense and 1 nonsense stop-gain variant, were located in exons 5, 6, or 7, which encode the central DNA-binding domain (exons 4-8).22 Moreover, 6 of 7 detected TP53 variants were reported as pathogenic in Li-Fraumeni syndrome23 and were predicted to be deleterious by SIFT and Polymorphism Phenotyping (PolyPhen), 5 of them affecting the known hot-spot residues R248 and R282.24

Next, we aimed at validating the hypothesis that the AF of TP53-positive subclones increases in subclonal AF during the evolution of relapse. In 4 of 6 patients in whom we identified TP53 variants at the time of initial diagnosis, an additional sample from the time of relapse was available (Table 3; supplemental Table 3A). Two patients had a medullary relapse, and relapse bone marrow or infiltrated nodal tissue was available for study (patients 9 and 153). The 2 remaining patients had an extramedullary relapse but only bone marrow sample was available for analysis (patients 41 and 95). We subjected these samples to exome sequencing that covered TP53 with a depth of 371 to 479 reads. In patient 9, the TP53-positive subclone expanded from an AF of 5.4% at initial diagnosis to 42% at relapse. In patient 95, the relapse bone marrow sample that was obtained 4 weeks after treatment of nodal relapse had been initiated was free of blasts by cytomorphology, but the 2 TP53 variants that had been present at initial disease were detected at frequencies of 6% and 9%, respectively. In patient 153 the subclonal TP53 variant remained subclonal at the time of relapse, suggesting alternative mechanisms of progression. Notably, exome sequencing of this patient identified an in-frame insertion in USP7 in this patient’s relapse sample (32/105 reads). The same insertion was found with low AF (1/8 reads) at initial diagnosis. The location of the in-frame insertion within the catalytic domain of USP7 suggests functional relevance. USP7 serves as an important regulator of MDM2 and TP53 metabolism and might therefore inactivate TP53.25-27 These findings suggest that the clonal selection in this patient may have been driven by USP7-dependent alterations of the p53-pathway. Despite the small number of patients for whom suitable material was available for study, these data indicate that progressive inactivation of TP53 can play a role in the evolution of relapse in patients with subclonal TP53 at diagnosis. These relapses can either be driven by expansion of the TP53-positive subclones or by acquiring new alterations inactivating the TP53 pathway.

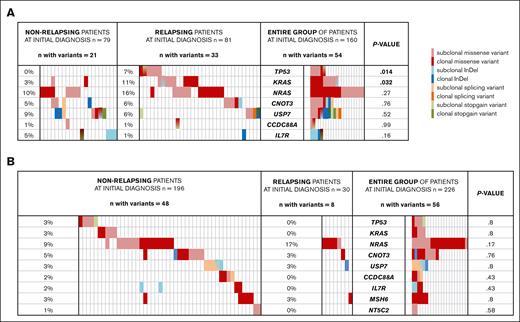

In addition to TP53, we also found KRAS variants (AF, 0.84%-45.54%) to be more frequent in relapsing (9/81) than in nonrelapsing (2/79) patients (P = .032; Figure 1A; supplemental Table 3B), consistent with the reported higher frequency of KRAS variants at relapse than at initial diagnosis in pediatric T-ALL.8 One patient (patient 110) carried a TP53 and a KRAS variant simultaneously. Most of the identified missense variants (9/11) were found at common hot spots (G12, n = 5; G13, n = 1; Q22, n = 1; and K117, n = 2), 4 were subclonal (AF < 30%), and 5 had an AF of ≥30%. Corresponding relapse samples were available for 5 of 9 patients with KRAS variants and were analyzed by Sanger sequencing. Clonal variants were confirmed to be present at the time of relapse in 3 patients (patients 110, 35, and 73), whereas the subclonal variants in 2 other patients (patients 75 and 77) were not identified at relapse. This is in line with the fact that KRAS variants have previously been shown to undergo both positive and negative selection during evolution of relapse.28

Variants detected at initial diagnosis of nonrelapsing and relapsing pediatric patients with T-ALL. Clonal variants (AF ≥ 30%) are shown in dark, and subclonal variants (AF < 30%) in light colors. Patients who did not carry variants of the genes analyzed are not included in this figure. The proportion of patients carrying variants of the respective genes is displayed in a percentage. Patients who carried >1 mutation of the same gene are depicted with mixed color codes. P values were calculated by χ2 test. Light red, subclonal missense variant; dark red, clonal missense variant; light blue, subclonal InDel; dark blue, clonal InDel; light orange, subclonal splicing variants; dark orange, clonal splicing variants; light green, subclonal stop-gain variants; and dark green, clonal stop-gain variants. (A) Variants found in cohort 1 of 81 relapsing and 79 matched nonrelapsing patients with T-ALL at initial diagnosis. TP53 variants were found in 6 relapsing and in none of the nonrelapsing patients (P = .014). RAS variants were found in 19 relapsing and in 9 nonrelapsing patients (P = .032). (B) Variants found in cohort 2 with 226 unselected consecutive patients with T-ALL at initial diagnosis of whom 196 were nonrelapsing and 30 relapsing. Variants of the target genes were identified in 48 of 196 nonrelapsing and 8 of 30 relapsing patients. Differences in variant frequency were not significant for any of the variants. InDel, insertion/deletion.

Variants detected at initial diagnosis of nonrelapsing and relapsing pediatric patients with T-ALL. Clonal variants (AF ≥ 30%) are shown in dark, and subclonal variants (AF < 30%) in light colors. Patients who did not carry variants of the genes analyzed are not included in this figure. The proportion of patients carrying variants of the respective genes is displayed in a percentage. Patients who carried >1 mutation of the same gene are depicted with mixed color codes. P values were calculated by χ2 test. Light red, subclonal missense variant; dark red, clonal missense variant; light blue, subclonal InDel; dark blue, clonal InDel; light orange, subclonal splicing variants; dark orange, clonal splicing variants; light green, subclonal stop-gain variants; and dark green, clonal stop-gain variants. (A) Variants found in cohort 1 of 81 relapsing and 79 matched nonrelapsing patients with T-ALL at initial diagnosis. TP53 variants were found in 6 relapsing and in none of the nonrelapsing patients (P = .014). RAS variants were found in 19 relapsing and in 9 nonrelapsing patients (P = .032). (B) Variants found in cohort 2 with 226 unselected consecutive patients with T-ALL at initial diagnosis of whom 196 were nonrelapsing and 30 relapsing. Variants of the target genes were identified in 48 of 196 nonrelapsing and 8 of 30 relapsing patients. Differences in variant frequency were not significant for any of the variants. InDel, insertion/deletion.

Besides TP53 and KRAS, variants of NRAS tended to be more common in relapsing patients (13/81) but were not significantly enriched in these patients compared with nonrelapsing patients (8/79; P = .27).

Notably, all patients who were identified to carry TP53 and/or KRAS variants at initial diagnosis (n = 14) died after relapse, whereas 19 of the remaining 67 patients without such variants survived the relapse, emphasizing the potential of subclonal TP53 and KRAS variants to serve as prognostic biomarkers at the time of diagnosis.

When considering all 9 of the putative HR genes, we identified 75 variants in 7 of these genes in a total of 54 (34%) of 160 patients with T-ALL (Figure 1A). There was a trend of variants to be more common in relapsing than in nonrelapsing patients (33 of 81 vs 21 of 79; P = .058). Most of the leukemias with variants (38/54) carried only a single variant in the selected genes, whereas 16 patients (10 relapsing and 6 nonrelapsing) harbored 2 to 4 variants simultaneously. The mean VAF of the identified variants was 24.7% (standard deviation, ± 18; range, 0.8-83). In 26 patients with a variant, corresponding remission samples were available. In 22 remission samples, the variants identified at initial diagnosis were not detected by Sanger sequencing at the time of remission, indicating that they were all somatic. Four variants identified at initial diagnosis (KRAS: E168fs; CCDC88A: L263F, R753C; and NT5C2: L100V) were shown to be constitutional by the analysis of the corresponding remission samples and excluded from our analysis. More than half of the variants (43/75) showed frequencies of <30% and were classified as subclonal, 25 of these were detected at an AF of <10%. The minimum VAF of identified variants was 0.84% (19/2257). Although we have not rigorously tested the sensitivity of our analysis for low-frequency somatic variants, with the stringent filtering criteria used we could detect variants at a frequency of 1% at a mean coverage of 1000 but could not sensitively detect variants at lower frequency. The same technique has previously detected variants of a 1% frequency with a sensitivity of 92%.29 Although the ultradeep sequencing technique was designed to identify variants with low AFs, it lacks sensitivity for the detection of large deletions.

The majority of the detected variants were nonsynonymous missense variants (n = 55; red; Figure 1A). In addition, we identified 3 splice-site variants (orange), 9 small insertions (blue), 2 small deletions (blue), and 6 stop-gain variants (green; Figure 1A). RAS variants were detected in 28 of 160 of the patients (17.5%; 19 relapsing and 9 nonrelapsing). The overall frequency of RAS variants is consistent with previously reported frequencies of 10% to 15% in T-ALL.30 We detected known gain-of-function hot-spot variants in NRAS (residues G12, n = 15; and G13, n = 2) and KRAS (G12, n = 5; G13, n = 1; Q22, n = 1; and K117: n = 2).30,31 Variants of USP7, a tumor suppressor inhibiting the ubiquitination of p53, were present in 12 patients (7.5%, 7 relapsing and 5 nonrelapsing). These variants affected 13 different residues of which 7 are located in the USP7 catalytic domain. Four nonrelapsing and 1 relapsing patient (3% of the entire cohort) harbored IL7R variants of which 4 occurred in known hot spots coding for leucin 242 and 243. Furthermore, we identified CNOT3 variants (subclonal, n = 7; and clonal, n = 2) in 9 of 160 patients (5 relapsing and 4 nonrelapsing) and subclonal CCDC88A variants in 2 of 160 patients (1 relapsing and 1 nonrelapsing). We did not detect any MSH6 or NT5C2 variants, which is consistent with previous findings that NT5C2 variants are relapse specific.10

Analysis of potential HR variants in unselected patients with T-ALL at initial diagnosis

To validate the potential prognostic value of variants in TP53, KRAS and the other 7 HR genes, we analyzed these genes in leukemia samples of 226 unselected patients with T-ALL (cohort 2), of whom 30 (13%) later developed a relapse. Overall, 66 variants (subclonal, n = 32; clonal, n = 34) were identified in 56 patients (25%; Figure 1B). There was no significant difference in variant frequency, variant types, or clonality between relapsing (8/30, 27%) and nonrelapsing (48/196, 25%) patients. The mean AF of the detected variants was 32.1% (standard deviation, ± 18.4; range, 2.2-97.8). Similar to the case-control cohort 1 and previously described frequencies in T-ALL,30,NRAS was the most frequently mutated gene found in 21 of 226 patients (16/196 nonrelapsing and 5/30 relapsing; P = .17; Figure 1B). Most of the identified RAS variants affected known gain-of-function hot-spot variants (NRAS: G12, n = 10; G13, n = 9; KRAS: G12, n = 2; G13, n = 2; and A146, n = 1).31 Neither TP53 nor KRAS was mutated in the group of 30 relapsing patients (Figure 1B). By contrast, 10 (5.2%) of 196 patients who did not develop a relapse harbored variants in either TP53 or KRAS (Table 6) at the time of initial diagnosis (P = .38). We detected 4 missense variants (AF, 3%-84.5%) and 1 stop-gain (AF, 10.1%) variant of TP53, 3 of these (R213X, Y234C, and R248W) were reported as pathogenic in Li-Fraumeni disease.23,32,33 The analysis of this unselected test cohort clearly showed that TP53 and KRAS variants cannot per se serve as reliable predictive biomarkers indicating the risk of relapse.

TP53 and KRAS variants identified in cohort 2

| Patient number . | Clinical risk group . | Gene . | AA change . | AF at initial diagnosis, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 353 | MR | TP53 | F113L | 3.0 |

| 327 | MR | TP53 | R248W | 8.4 |

| 227 | MR | TP53 | R213X | 10.1 |

| 215 | MR | TP53 | T253S | 13.6 |

| 386 | SR | TP53 | Y234C | 84.5 |

| 191 | MR | KRAS | G12D | 11.3 |

| 289 | MR | KRAS | G13D | 12.9 |

| 166 | MR | KRAS | G13C | 27.6 |

| 194 | MR | KRAS | A146V | 34.7 |

| 187 | MR | KRAS | G12V | 40.6 |

| Patient number . | Clinical risk group . | Gene . | AA change . | AF at initial diagnosis, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 353 | MR | TP53 | F113L | 3.0 |

| 327 | MR | TP53 | R248W | 8.4 |

| 227 | MR | TP53 | R213X | 10.1 |

| 215 | MR | TP53 | T253S | 13.6 |

| 386 | SR | TP53 | Y234C | 84.5 |

| 191 | MR | KRAS | G12D | 11.3 |

| 289 | MR | KRAS | G13D | 12.9 |

| 166 | MR | KRAS | G13C | 27.6 |

| 194 | MR | KRAS | A146V | 34.7 |

| 187 | MR | KRAS | G12V | 40.6 |

Among the 226 analyzed T-ALL patients, 5 non-relapsing patients showed functionally damaging TP53 variants and another 5 functionally damaging variants of KRAS at initial diagnosis. None of the relapsing patients harbored TP53 or KRAS variants.

AA, amino acid; MR, medium risk; SR standard risk.

Noting that all patients with subclonal but also clonal TP53 and KRAS variants in the unselected test cohort who did not develop a relapse showed a favorable early treatment response (Table 5), we analyzed whether the predictive value of the TP53 and KRAS variants were influenced by treatment response serving as an integrated marker of other resistance and progression mechanisms. We performed this analysis in the entire group of 386 patients, of whom the treatment response status (treatment group) was known in 385. Of these, 188 were stratified to HR with poor treatment response and 197 to non-HR. HR is defined by poor response to initial steroid therapy, no complete remission after induction (day 33), and a PCR-MRD after consolidation (day 78) ≥5 × 10−4. In the 2009 and 2017 trials, additionally flow cytometry (FCM)-MRD in the bone marrow on day 15 of ≥10% identified HR patients. In the non-HR groups, 42 patients developed a relapse: 6 of 17 (35%) with a TP53/KRAS variant and 36 of 180 (20%) without (P = .14; Table 7). In the HR group, 69 patients developed a relapse: 8 of 9 (89%) with a TP53/KRAS variant and 61 of 179 (34%) without (P = .001; Table 8). Of the relapsing patients with TP53/KRAS variants, none survived whereas those without showed an event-free survival of 26.2%, thus highlighting the particularly dismal prognosis of relapsing patients with TP53/KRAS variants (Figure 2A). Furthermore, patients who carry subclonal or clonal TP53/KRAS variants at initial diagnosis and show a poor treatment response appear to be at a particularly HR of developing a fatal relapse (Figure 2C).

Relapse rate of non-HR patients with or without TP53/KRAS variants

| . | Relapse . | No relapse . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53/KRAS positive | 6 (35%) | 11 | 17 |

| TP53/KRAS negative | 36 (20%) | 144 | 180 |

| Total | 42 (21%) | 155 | 197 |

| . | Relapse . | No relapse . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53/KRAS positive | 6 (35%) | 11 | 17 |

| TP53/KRAS negative | 36 (20%) | 144 | 180 |

| Total | 42 (21%) | 155 | 197 |

In the group of patients with non-HR treatment response, 35% of patients with TP53 and/or KRAS variants and 20% of the patients without such variants experienced a relapse.

Relapse rate of HR patients with or without TP53/KRAS variants

| . | Relapse . | No relapse . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53/KRAS positive | 8 (89%) | 1 | 9 |

| TP53/KRAS negative | 61 (34%) | 118 | 179 |

| Total | 69 (37%) | 119 | 188 |

| . | Relapse . | No relapse . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53/KRAS positive | 8 (89%) | 1 | 9 |

| TP53/KRAS negative | 61 (34%) | 118 | 179 |

| Total | 69 (37%) | 119 | 188 |

In the group of patients with HR treatment response, 89% of patients with TP53 and/or KRAS variants experienced a relapse. In contrast, only 34% of the remaining 179 patients without such variants relapsed later on.

Kaplan-Meier plots of event-free survival after relapse in all 111 relapsing patients. (A) All patients who carry TP53 and/or KRAS variants at initial diagnosis vs patients without such variants. (B) Patients in the standard-risk (SR) or medium-risk (MR) group who carry TP53 and/or KRAS variants at initial diagnosis vs SR/MR patients without such variants. (C) Patients in the HR group who carry TP53 and/or KRAS variants at initial diagnosis vs HR patients without such variants.

Kaplan-Meier plots of event-free survival after relapse in all 111 relapsing patients. (A) All patients who carry TP53 and/or KRAS variants at initial diagnosis vs patients without such variants. (B) Patients in the standard-risk (SR) or medium-risk (MR) group who carry TP53 and/or KRAS variants at initial diagnosis vs SR/MR patients without such variants. (C) Patients in the HR group who carry TP53 and/or KRAS variants at initial diagnosis vs HR patients without such variants.

Discussion

The stratification of treatment intensity in T-ALL in most international treatment protocols predominantly relies on treatment response. Despite concerted efforts by numerous research groups, reliable prognostic biomarkers indicative of relapse have yet to be validated and clinically established.34-36 Against this background, the most relevant finding reported here is that subclonal TP53 and KRAS alterations identified at the time of initial diagnosis, along with a poor treatment response characterize a subset of children with T-ALL who face a dismal prognosis and may benefit from alternative treatment approaches. This finding complements recent progress in the identification of clonal genomic prognostic biomarkers for T-ALL in a comprehensive analysis of 1300 children and young adults. This study showed that a variety of novel structural variants, in particular in noncoding regions, can drive T-ALL and can, in some cases, predict prognosis independently of MRD responses.6 In addition, the clonal identification of variants within several genes, notably RAS and TP53, at the time of relapse has previously been associated with an adverse prognosis.8,9 In a singular case, we were able to trace a clonal TP53 variant detected at relapse back to a subclone harboring this variant at initial diagnosis. Consequently, we postulated that subclonal TP53 variants present at initial diagnosis might portend the risk of relapse. As an important novel finding, this case-control cohort demonstrates that subclonal HR variants identified at the time of initial diagnosis can indeed expand during the progression to relapse. Specifically, in the case-control cohort, subclonal TP53 and KRAS variants were found to be either exclusively present or significantly enriched, respectively, in patients experiencing relapse at the time of initial diagnosis. All of these patients showed a very poor outcome, with none surviving the relapse, which suggests that TP53 and KRAS variants at initial diagnosis may signify a very poor prognosis in T-ALL. Furthermore, the proportion of relapsing patients who carry a TP53 variant at initial diagnosis approximately reflects the proportion of TP53-positive T-ALL relapses,8,9 indicating that a substantial proportion of the rare TP53-mutated relapses may be preceded by subclonal TP53 variants at first diagnosis. We predominantly identified TP53 variants that affect the hot spot R248. TP53 variants at this position are characterized by a gain of oncogenic potential37 and are associated with shorter survival,38 enhanced proliferation, and a propensity for dissemination of T-ALL in mouse models,39 thus emphasizing their functional potential to contribute to disease progression and to evolution of relapse. However, it needs to be acknowledged that the ultradeep sequencing technology that we used in this study is not suitable for the identification of TP53 deletions. However, we do not consider this limitation to affect the conclusions of this study, because such deletions only account for ∼5% of all TP53 variants.40

Despite the clear-cut data emerging from our case-control cohort, validation in our unbiased cohort consisting of consecutive patients unequivocally indicates that such subclonal variants alone cannot serve as reliable biomarkers for risk assessment. Among 30 patients who relapsed from this cohort, none exhibited a variant in TP53 or in KRAS. In contrast, ∼5% of patients who remained in complete remission harbored such a variant.

It remains an open question how the discrepancies of the findings in cohorts 1 and 2 can be explained. In principle, changes in treatment protocols may be considered as a potential confounder. However, during the evolution of BFM protocols for the treatment of T-ALL only minor differences have been introduced since the BFM-ALL 1995 protocol had been launched. These changes include the introduction of dexamethasone during induction for patients with prednisone good response as a result of a randomization in BFM-ALL 2000, an additional dose of cyclophosphamide during induction for patients with prednisone poor response in the BFM-2009 protocol, and the reinduction (“protocol II” in ALL-BFM 2000, 3× “protocol III” for HR patients from BFM-ALL 2009) and the stratification based on fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-MRD on day 15 from the BFM-2009 protocol. Although we cannot exclude an effect of these changes in treatment with certainty, we do not consider that these changes that did not touch the architecture of the protocol sufficient to explain the differences in the prognostic effect of subclonal TP53/KRAS variants. As a more likely explanation, we noted that all patients with TP53/KRAS mutations in cohort 2 showed a favorable early treatment response whereas 10 of 16 such patients in cohort 1 responded poorly to the induction chemotherapy. Drawing inspiration from the success of the IKZFplus-risk signature in precursor B-cell ALL,41 we subsequently conducted an analysis encompassing the entire cohort of 386 patients (including the 188 HR and the 197 non-HR patients with or without TP53/KRAS variants), which comprises most of the patients who relapsed after treatment on BFM-ALL trials between 1995 and 2017, combining subclonal and clonal genotype data with treatment response. This analysis identified a small subset of 9 of 386 patients with T-ALL (2.3%) exhibiting poor treatment response and harboring subclonal and clonal TP53/KRAS variants at initial diagnosis. Of 9 patients, 8 relapsed and died, resulting in a positive predictive value of 89% (Tables 4 and 8. Although this patient cohort was representative of all patients that have been treated in recent AIEOP-BFM ALL trials (Table 1), it is crucial to acknowledge that this composite risk signature was only present in a small minority of T-ALL cases at initial diagnosis, necessitating validation in an independent cohort before its clinical application for risk stratification and possibly intensified or even experimental treatment concepts. Assuming a risk of relapse of 21% and a rate of positivity for subclonal TP53/KRAS of 13% in patients later developing a relapse, we estimate that ∼200 children with T-ALL with a poor treatment response would need to be analyzed in such a validation cohort thus requiring international collaboration in a next phase of this study.

In perspective, patients harboring subclonal and clonal TP53 and/or KRAS variants exhibiting poor treatment response may potentially derive benefit from treatment intensification strategies, including stem cell transplantation or innovative approaches such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy targeting CD7 or CD1a during their initial remission period. Additionally, TP53-stabilizing agents such as the prodrug APR-246 or other TP53-targeted therapies could be considered as viable options for patients experiencing T-ALL relapse with TP53 mutations, possibly extending to those presenting with TP53-mutated subclones at the time of diagnosis.

The implementation of risk stratification based on TP53 and KRAS variants into clinical practice necessitates overcoming technical challenges. Firstly, establishing a reliable and reproducible quantitative method capable of capturing subclonal variants within a clinically relevant timeframe is imperative. Secondly, using such a method requires the definition of clinically validated thresholds that incorporate treatment response data to guide decisions regarding treatment escalation or the use of experimental therapies. Finally, the efficacy of treatment intensification in this specific subgroup needs validation, a task complicated by the limited size of the ultra-HR subgroup, necessitating reliance on historical controls.

In conclusion, TP53 and KRAS variants, both subclonal and clonal, identified at initial diagnosis are disproportionately present in patients with T-ALL who subsequently experience relapse. Although these variants do not predict relapse in patients with favorable early treatment responses, our findings indicate that nearly all patients with TP53 and/or KRAS variants exhibiting poor early treatment response to their front-line protocol ultimately relapse. Consequently, early molecular risk stratification in such patients may facilitate the implementation of intensified or innovative treatment modalities, potentially improving outcomes.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to support language editing. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the European Molecular Biology Laboratory Information Technology and GeneCore facilities for their excellent technical support and provision of high-performance computing resources for this study.

Authorship

Contribution: T.K. was involved in all aspects of the project including conceptualization, design, acquisition and analysis of the data, and manuscript preparation; A.E.K., J.B.K., and P.R.-P. designed the study, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript; K.M. was responsible for recruitment of cohort 1; T.R. was responsible for technical assistance and data analysis; B.E.-U. provided material and technical support; C.E., M.Z., M. Stanulla, M. Schrappe, G.C., and S.K. provided material support and clinical data; M.Z. performed statistical analyses; J.O.K. contributed to data interpretation; and all authors critically reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andreas E. Kulozik, Department of Pediatric Oncology, Hematology and Immunology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 430, Heidelberg N/A 69120, Germany; email: andreas.kulozik@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

References

Author notes

J.B.K. and A.E.K. contributed equally to this study.

The data reported in this article have been deposited in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (accession number EGAD50000001168).

The accession number for the data of the ultradeep sequencing will be provided upon acceptance of this manuscript for publication.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.