Key Points

Venetoclax plus low-intensity chemotherapy can be safely administered in ALL.

Venetoclax plus low-intensity chemotherapy is a promising therapy in older patients with newly diagnosed, high-risk ALL.

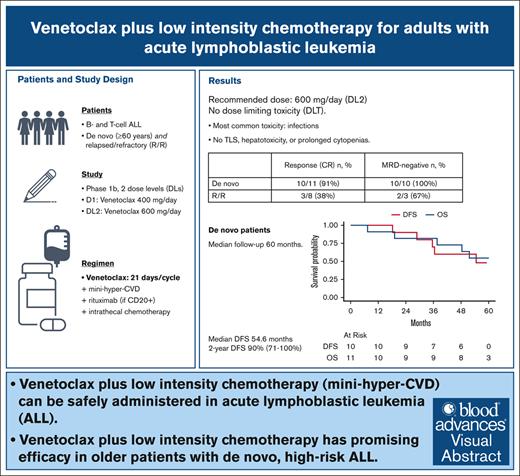

Visual Abstract

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor venetoclax may enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy, allowing dose reductions. This phase 1b study of venetoclax plus attenuated chemotherapy enrolled 19 patients with ALL either newly diagnosed (aged ≥60 years, n = 11 [B-cell, n = 8; T-cell, n = 3]) or relapsed/refractory (R/R; aged ≥18 years, n = 8 [B-cell, n = 3; T-cell, n = 5]). Venetoclax was given for 21 days with each cycle of mini–hyper-CVD (mini-HCVD; cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dexamethasone alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine). There were no dose-limiting toxicities at dose level 1 (DL1; n = 3, 400 mg/d) or DL2 (n = 6, 600 mg/d); DL2 was the recommended phase 2 dose and explored further (n = 10). The most common nonhematologic adverse events were grade ≥3 infections. There were no deaths within 60 days. There was no tumor lysis syndrome, hepatotoxicity, prolonged cytopenias, or early discontinuation for toxicity. Among patients with newly diagnosed ALL, 10 of 11 (90.9%) achieved a measurable residual disease–negative (<0.01% sensitivity) complete remission (CR) including 6 patients with hypodiploid TP53-mutated ALL. All patients in CR bridged to hematopoietic stem cell transplant (n = 9) or completed protocol (n = 1). With a median follow-up of 60 months, median disease-free survival (DFS) for patients with newly diagnosed ALL was 54.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 35.5 to not available), with a 2-year DFS rate of 90% (95% CI, 71-100). Among patients with R/R ALL, 3 of 8 (37.5%) achieved CR. In summary, for patients with newly diagnosed ALL, venetoclax plus mini-HCVD is well tolerated with promising efficacy. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03319901.

Introduction

Adults with relapsed or refractory (R/R) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) as well as older adults with newly diagnosed disease have poor outcomes because of resistant disease and poor tolerance of conventional chemotherapy.1,2

Outcomes for patients with R/R B-cell ALL (B-ALL) have improved with the approvals of blinatumomab, a bispecific CD19-CD3 T-cell engager, and inotuzumab ozogamicin (inotuzumab), an anti-CD22 antibody-drug conjugate, which are superior to salvage chemotherapy.3,4 However, remissions induced by inotuzumab and blinatumomab are not usually durable, and these agents cannot be applied to relapsed T-cell ALL (T-ALL). CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy represents another major advance but is also limited to B-ALL.5 An unmet need exists for patients with relapsed ALL who are ineligible for, intolerant of, or who have failed, available therapies.6

For older adults with newly diagnosed ALL, there is interest in combining novel agents with reduced doses of conventional chemotherapy in order to improve efficacy and reduce toxicity.7,8 Inotuzumab has been studied in induction alone and in combination with attenuated chemotherapy.9-11 However, some patients are not eligible for inotuzumab-based therapy because of CD22− disease (T-ALL) or comorbidity (mainly hepatic), and there are concerns regarding short- and long-term toxicities of inotuzumab-based regimens. Blinatumomab has also been studied as induction therapy for older adults; however, blinatumomab appears to be better suited for the postremission setting because response rates are lower in the setting of significant disease burden.12,13 Innovation for older adults with T-ALL has been constrained by the lack of targeted agents that can easily replace, or be combined with, conventional chemotherapy. Nelarabine, a nucleoside analogue approved for relapsed T-ALL, has been explored in the first-line setting with mixed results.14-16

Lymphoblasts have been shown to be sensitive to the B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor, venetoclax, which may enhance response to chemotherapy including in high-risk genetic subtypes.17-23 We hypothesized that venetoclax in combination with attenuated conventional chemotherapy would offer an effective and well-tolerated regimen for adult patients with ALL. Here, we report our multicenter phase 1 study of venetoclax plus low-intensity chemotherapy in older adults (aged ≥60 years) with newly diagnosed disease and adults with R/R B-cell and T-ALL.

Methods

Trial design

We conducted a phase 1b investigator-sponsored study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03319901) at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA) and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both institutions. All patients provided informed consent. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All authors had access to primary data, conducted the analyses, and wrote the manuscript.

Participants

We enrolled patients aged ≥60 years with previously untreated Philadelphia chromosome–negative B-cell or T-ALL and patients aged ≥18 years with R/R ALL (no prior therapy limit). Additional eligibility criteria included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of ≤2 and adequate organ function (total bilirubin of ≤2 × upper limit of normal, liver transaminases of ≤3.0 × upper limit of normal, creatinine clearance of >50 mL/min, and cardiac ejection fraction of >40%). Patients were ineligible if they had no marrow disease, were Philadelphia chromosome positive, or had symptomatic central nervous system disease. Patients with a history of another malignancy were excluded unless the malignancy was definitively treated, low-grade requiring only observation (prostate cancer or meningioma), or multiple myeloma in remission (without detectable paraprotein) for ≥1 year. No chemotherapy within 14 days except hydroxyurea, corticosteroids, and/or a single dose of cytarabine was permitted.

Treatment

Before chemotherapy, venetoclax was ramped up to target dose level (DL; DL1: 400 mg/d; DL2: 600 mg/d) over 6 days (Table 1). After completion of the single-agent venetoclax ramp-up, venetoclax was administered for 21 days per cycle with the mini-hyper-CVD (mini-HCVD) regimen (hyper-fractioned “A” cycles of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dexamethasone alternating with “B” cycles of methotrexate and cytarabine; Table 1).9,24,25 Patients were required to discontinue any strong cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) inhibitors during venetoclax ramp-up. After the ramp-up, venetoclax was dose reduced when patients received moderate CYP3A4 or p-glycoprotein inhibitor (by 50%), strong CYP3A4 inhibitor (by 75%), and posaconazole (by 83%).

Study regimen

| Phase . | Treatment details . |

|---|---|

| Venetoclax ramp-up | DL1 (400 mg daily) |

| Ramp-up: day 1, 20 mg; day 2, 50 mg; day 3, 100 mg; day 4, 200 mg; days 5 and 6, 400 mg | |

| DL2 (600 mg daily) | |

| Ramp-up: day 1, 50 mg; day 2, 100 mg; day 3, 200 mg; day 4, 400 mg; days 5 and 6, 600 mg | |

| Venetoclax plus mini-HCVD | Venetoclax (by mouth) daily, days 1-21, per DL (DL1, 400 mg; DL2, 600 mg) |

| A cycles (1, 3, 5, and 7) | |

| Cyclophosphamide (IV) 150 mg/m2 twice daily, days 1-3 | |

| Vincristine (IV) 2 mg, days 1 and 8 | |

| Dexamethasone (IV or by mouth) 20 mg daily, days 1-4, 8-11 | |

| Rituximab (IV) 375 mg/m2, days 2 and 8, cycles 1 and 3 (if CD20+ of ≥1%) | |

| IT cytarabine/IT methotrexate | |

| B cycles (2, 4, 6, and 8) | |

| Methotrexate (IV) 250 mg/m2, day 1 | |

| Cytarabine (IV) 500 mg/m2 twice daily, days 2 and 3 | |

| Methylprednisolone (IV) 50 mg twice daily, days 1-3 | |

| IT cyatarabine/IT methotrexate | |

| Rituximab (IV) 375 mg/m2, days 2 and 8, cycles 2 and 4 (in CD20+ of ≥1%) | |

| Venetoclax plus POMP | Venetoclax (by mouth) daily 400 mg, days 1-28 |

| 6 mercaptopurine 50 mg (by mouth) twice daily, days 1-28 | |

| Vincristine 2 mg (IV), day 1 | |

| Methotrexate 10 mg/m2 (by mouth), days 1, 8, 15, and 22 | |

| Prednisone 50 mg (by mouth) daily, days 1-5 |

| Phase . | Treatment details . |

|---|---|

| Venetoclax ramp-up | DL1 (400 mg daily) |

| Ramp-up: day 1, 20 mg; day 2, 50 mg; day 3, 100 mg; day 4, 200 mg; days 5 and 6, 400 mg | |

| DL2 (600 mg daily) | |

| Ramp-up: day 1, 50 mg; day 2, 100 mg; day 3, 200 mg; day 4, 400 mg; days 5 and 6, 600 mg | |

| Venetoclax plus mini-HCVD | Venetoclax (by mouth) daily, days 1-21, per DL (DL1, 400 mg; DL2, 600 mg) |

| A cycles (1, 3, 5, and 7) | |

| Cyclophosphamide (IV) 150 mg/m2 twice daily, days 1-3 | |

| Vincristine (IV) 2 mg, days 1 and 8 | |

| Dexamethasone (IV or by mouth) 20 mg daily, days 1-4, 8-11 | |

| Rituximab (IV) 375 mg/m2, days 2 and 8, cycles 1 and 3 (if CD20+ of ≥1%) | |

| IT cytarabine/IT methotrexate | |

| B cycles (2, 4, 6, and 8) | |

| Methotrexate (IV) 250 mg/m2, day 1 | |

| Cytarabine (IV) 500 mg/m2 twice daily, days 2 and 3 | |

| Methylprednisolone (IV) 50 mg twice daily, days 1-3 | |

| IT cyatarabine/IT methotrexate | |

| Rituximab (IV) 375 mg/m2, days 2 and 8, cycles 2 and 4 (in CD20+ of ≥1%) | |

| Venetoclax plus POMP | Venetoclax (by mouth) daily 400 mg, days 1-28 |

| 6 mercaptopurine 50 mg (by mouth) twice daily, days 1-28 | |

| Vincristine 2 mg (IV), day 1 | |

| Methotrexate 10 mg/m2 (by mouth), days 1, 8, 15, and 22 | |

| Prednisone 50 mg (by mouth) daily, days 1-5 |

IT, intrathecal.

Patients were treated with up to 8 cycles of venetoclax plus mini-HCVD (4 “A” cycles alternating with 4 “B” cycles), with cycles administered every 28 days pending recovery of blood counts (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] of ≥1.0 × 103/μL and platelets of ≥100 × 103/μL; or ANC of ≥0.5 × 103/μL and platelets of ≥75 × 103/μL by day 42). Rituximab was administered to any patient with CD20 expression of ≥1% by flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry.26 Intrathecal chemotherapy was administered for 8 doses. Granulocyte growth factor (pegfilgrastim 6 mg, or equivalent) and prophylactic antimicrobial therapy was administered per local standards. Patients received <8 cycles of mini-HCVD in the setting of toxicity, lack of response, or if consolidated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) per physician discretion. After completion of venetoclax plus mini-HCVD “intensive” phase, patients received low-intensity POMP (6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, vincristine, and prednisone) maintenance for 24 1-month cycles with venetoclax 400 mg daily.

Venetoclax dose reductions were recommended (decreased number of days per cycle) during intensive phase after achievement of complete remission (CR) in settings of delayed or incomplete count recovery. During POMP maintenance, venetoclax was interrupted and then dose reduced (mg per day and/or days per cycle) in the setting of grade 4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia.

Study design, end points, and statistical analyses

The study was conducted as a 3+3 design with an expansion cohort of 10 patients. The primary objective of the study was to identify a maximum tolerated dose/recommended phase 2 dose of venetoclax in combination with mini-HCVD. The purpose of the expansion cohort was to further confirm safety and to gather preliminary evidence of antitumor efficacy. A dose limiting toxicity was defined as failure to achieve blood count recovery (ANC ≥0.5 × 103/μL, or platelet count ≥25 × 103/μL) by day 42 from chemotherapy initiation in responding patients, or grade 3 to 5 nonhematologic toxicities at least possibly attributable to venetoclax during the first 28 days of treatment. Toxicities were assessed via the revised National Cancer Institute common terminology criteria for adverse events version 4.0. Secondary objectives were to evaluate efficacy by measuring CR rate, rate of achievement of measurable residual disease (MRD) negative remission, disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS).

CR was defined as <5% marrow blasts, no evidence of extramedullary or central nervous system leukemia, ANC of ≥1.0 × 103/μL, and platelets of ≥100 × 103/μL. CR with incomplete platelet count (CRp) was defined as CR except for platelet count of <100 × 103/μL. MRD was evaluated by multiparameter flow cytometry, with negative defined as <0.01% (10−4). DFS was defined as time from CR/CRp response to relapse or death from any cause and censored at the time last known alive and relapse free. OS was defined as time from registration to last follow-up or death and censored at the time last known alive.

Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were summarized as median and range. DFS and OS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Median DFS and OS are reported as well as 2-year DFS and OS rates with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) estimated using the Greenwood formula. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2.

Correlative science: BH3 profiling and CyTOF assay

B-cell lymphoma (BCL)-2 homology domain 3 (BH3) profiling was performed as previously described27; details can be found in the supplemental Methods. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from blood or bone marrow sample via Ficoll gradient. Plasma membranes of peripheral blood mononuclear cells were permeabilized with digitonin followed by BH3 peptides (BCL-2 associated death promoter [BAD], myeloid cell leukemia-1 specific peptide 1 [MS1]) or venetoclax treatment for 60 minutes. Immunofluorescent detection of cytochrome-c signal of cells was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, cells of interest were gated as CD19+CD45lowSSClow for B-ALL and CD45lowSSClow for T-ALL. Mitochondrial sensitivity to individual peptides relates to magnitude of cytochrome-c released across the population. The BCL2 associated agnoist of cell death (BAD) peptide indicates dependence on BCL-2, BCL-extra large (XL), or BCL-w; venetoclax indicates dependence on BCL-2; MS1 indicates dependence on myeloid cell leukemia-1 (MCL-1). Cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF) assay was also performed, and the obtained data were analyzed as described previously (see the supplemental Methods).28,29

Results

Patients

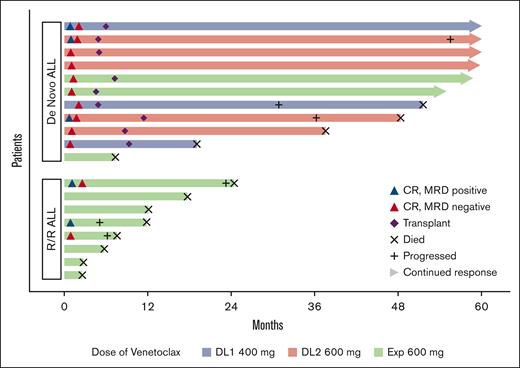

In total, 19 patients were enrolled between November 2017 and August 2019 (Table 2; Figure 1). Among the 11 newly diagnosed patients (B-cell, n = 8; T-cell, n = 3), the median age was 68 years (range, 61-78; age of ≥70 years, n = 4 [36%]). High-risk genetics were common (6/11 hypodiploid/near triploid karyotype with mutation in TP53) of whom 3 had previously been treated for multiple myeloma (2 with prior lenalidomide exposure, and 2 with previous autologous stem cell transplant). The 8 relapsed patients were had primarily T-ALL (5/8, 62.5%) with frequent presence of TP53 (6/8) and heavily pretreated (median of 2 lines of therapy [range, 1-5]; 5/8 [62.5%] were relapsed after HSCT).

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics . | Total . | R/R . | Newly diagnosed . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 19 | n = 8 | n = 11 | |

| Age, median (range), y | 64 (23-82) | 45.5 (23-82) | 68 (61-78) |

| Male/female | 15/4 | 6/2 | 9/2 |

| Immunophenotype | |||

| B-cell (CD20+) | 11 (7) | 3 (0) | 8 (7) |

| T-cell (ETP) | 8 (4) | 5 (3) | 3 (1) |

| Cytogenetics | |||

| Normal | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Complex | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Hypodiploid/near-triploid | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Hyperdiploid | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| TP53 mutation | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Prior therapy | |||

| Median prior lines (range) | — | 2 (1-5) | — |

| Prior HSCT | — | 5 | — |

| Therapy related (multiple myeloma) | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Characteristics . | Total . | R/R . | Newly diagnosed . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 19 | n = 8 | n = 11 | |

| Age, median (range), y | 64 (23-82) | 45.5 (23-82) | 68 (61-78) |

| Male/female | 15/4 | 6/2 | 9/2 |

| Immunophenotype | |||

| B-cell (CD20+) | 11 (7) | 3 (0) | 8 (7) |

| T-cell (ETP) | 8 (4) | 5 (3) | 3 (1) |

| Cytogenetics | |||

| Normal | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Complex | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Hypodiploid/near-triploid | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Hyperdiploid | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| TP53 mutation | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Prior therapy | |||

| Median prior lines (range) | — | 2 (1-5) | — |

| Prior HSCT | — | 5 | — |

| Therapy related (multiple myeloma) | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Patient response and outcomes in newly diagnosed and R/R patients. MRD with sensitivity of <0.01%.

Patient response and outcomes in newly diagnosed and R/R patients. MRD with sensitivity of <0.01%.

Toxicity

Three patients were treated at DL1 (400 mg daily), and 6 patients were treated at DL2 (600 mg daily). There were no protocol-defined dose-limiting toxicities during dose escalation and thus venetoclax 600 mg daily was declared recommended phase 2 dose. Subsequently, 10 patients were treated in an expansion cohort at venetoclax 600 mg daily.

All patients were eligible for safety analysis. There was no evidence of clinical tumor lysis syndrome during the venetoclax ramp-up or after initiation of chemotherapy. Infections (including febrile neutropenia, bacteremia, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection) were the most common grade ≥3 nonhematologic toxicities, including among 7 of 19 (36.8%) patients during cycle 1. Among patients who achieved CR/CRp, grade ≥3 infections were seen in 13 of 39 (33.3%) postremission consolidation cycles. There were no deaths within 60 days from registration and no deaths in remission on study. Nonhematologic grade 3 adverse events that occurred in ≥2 patients are listed in Table 3.

Nonhematologic adverse events, grade 3 and higher occurring in 2 or more patients

| . | All grades . | Grade ≥3 . |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||

| Diarrhea or colitis, n (%) | 11 (58) | 3 (16) |

| Infections and infestations | ||

| Other infections or sepsis, n (%) | 10 (53) | 7 (42) |

| Lung infection, n (%) | 5 (26) | 5 (26) |

| Febrile neutropenia, n (%) | 13 (68) | 13 (68) |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | ||

| Hyperglycemia, n (%) | 4 (21) | 3 (16) |

| Hypocalcemia, n (%) | 3 (16) | 2 (11) |

| Vascular disorders | ||

| Hypotension, n (%) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) |

| . | All grades . | Grade ≥3 . |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||

| Diarrhea or colitis, n (%) | 11 (58) | 3 (16) |

| Infections and infestations | ||

| Other infections or sepsis, n (%) | 10 (53) | 7 (42) |

| Lung infection, n (%) | 5 (26) | 5 (26) |

| Febrile neutropenia, n (%) | 13 (68) | 13 (68) |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | ||

| Hyperglycemia, n (%) | 4 (21) | 3 (16) |

| Hypocalcemia, n (%) | 3 (16) | 2 (11) |

| Vascular disorders | ||

| Hypotension, n (%) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) |

No patients discontinued protocol treatment because of therapy-related toxicity. Dose reductions were implemented in 2 patients treated at DL2 (600 mg daily); 1 patient was decreased to 400 mg daily after 1 cycle because of investigator decision, and another after 3 cycles of therapy because of prolonged thrombocytopenia. Venetoclax was held mid-cycle in 2 patients because of a lung infection and neutropenia, with the former patient able to resume treatment the next cycle without dose reduction, and the latter patient found to be relapsed at the end of the cycle.

Among all patients, the median time from cycle 1 to cycle 2 of mini-HCVD was 28 days (range, 21-42), from cycle 2 to cycle 3 was 29 days (range, 24-42), and from cycle 3 to cycle 4 was 31 days (range, 27-41). Similar results were seen when considering newly diagnosed and responding patients only. All patients received ≤5 cycles except 1 patient (patient 4) who received 8 cycles. For patient 4, time between cycles was: cycle 5 to cycle 6, 57 days; cycle 6 to cycle 7, 48 days; and cycle 7 to cycle 8, 31 days.

Response and survival

Among patients with newly diagnosed disease, 10 of 11 (90.9%) achieved CR (n = 9 after 1 cycle, n = 1 after 2 cycles), with all 10 responding patients achieving MRD-negative (<0.01% by flow cytometry) remission (n = 6 after 1 cycle, n = 4 after 2 cycles). The median number of cycles received among responding patients was 4 (range, 3-8). The remissions facilitated HSCT consolidation in 9 patients (median time to HSCT, 182 days; range 138-347), whereas 1 patient who was ineligible for HSCT because of age (aged 78 years at registration) remained on study and completed 4 cycles of mini-HCVD followed by 24 cycles of POMP maintenance and remained in ongoing CR at completion of 5-year follow-up. The patient failing to achieve CR had early T-cell precursor (ETP) ALL. Note, 3 of 3 patients treated at DL1 (400 mg daily) achieved MRD-negative CR and were received HSCT.

Among the 9 patients who were consolidated with HSCT, 2 (22%) patients died of HSCT complications (9.8 and 28.8 months after HSCT, respectively) and 3 experienced very late relapses at 28.7, 35.5, and 54.5 months from CR, respectively. At the last follow-up, 44% (4/9) of patients remain in long-term remission (2 completed 5 years of follow-up, and 2 were 4.6 and 4.9 years from registration at data lock, respectively). Among the 3 patients who relapsed after HSCT, 1 patient with B-ALL was treated with brexucabtagene autoleucel therapy and remains alive in ongoing remission at 5 years of follow-up whereas another patient with B-ALL achieved a second CR after retreatment with venetoclax and mini-HCVD but subsequently died of complications of a second HSCT. The final relapsed patient with T-ALL received multiple salvage therapies but ultimately was refractory and died 12.1 months from relapse.

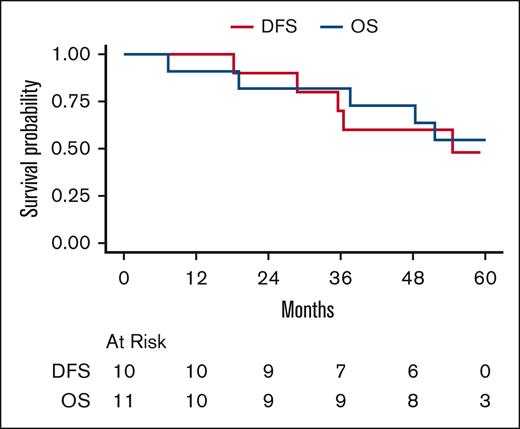

Patients with newly diagnosed disease had median follow-up of 60.0 months (95% CI, 58.8 to NA). Median DFS was 54.6 months (95% CI, 35.5 to NA). The 1- and 2-year DFS rates were 100% and 90% (95% CI, 71-100), respectively. Median OS was not reached. The 1-, 2-, and 5-year OS rates were 91% (95% CI, 74-100), 82% (95% CI, 59-100), and 55% (95% CI, 25-84), respectively (Figure 2).

Survival of newly diagnosed patients. DFS and OS in newly diagnosed patients. Median DFS is 54.6 months (95% CI, 35.5 to NA). DFS at 1 and 2 years is 100% and 90% (95% CI, 71-100), respectively. 5-year DFS is NA. Median OS is NA. OS at 1, 2, and 5 years is 91% (95% CI, 74-100), 82% (95% CI, 59-100), and 55% (95% CI, 25-84), respectively.

Survival of newly diagnosed patients. DFS and OS in newly diagnosed patients. Median DFS is 54.6 months (95% CI, 35.5 to NA). DFS at 1 and 2 years is 100% and 90% (95% CI, 71-100), respectively. 5-year DFS is NA. Median OS is NA. OS at 1, 2, and 5 years is 91% (95% CI, 74-100), 82% (95% CI, 59-100), and 55% (95% CI, 25-84), respectively.

Among patients with R/R ALL, 3 of 8 (37.5%; B-cell, 1/3; T-cell, 2/5) achieved CR (n = 2) or CRp (n = 1), with 2 achieving MRD-negative remission (<0.01% by MPFC). The responding patient with B-ALL had mutated TP53 and achieved MRD-negativity with remission (CRp) sustained for 5.3 months (note this patient had received prior inotuzumab and blinatumomab). The 2 remissions achieved by patients with R/R T-ALL were sustained for 4.2 (MRD-positive CR) and 22.1 months, respectively. None of the 3 responding patients received transplantation (1 patient was not eligible because of age, and the other 2 patients had previously received HSCT).

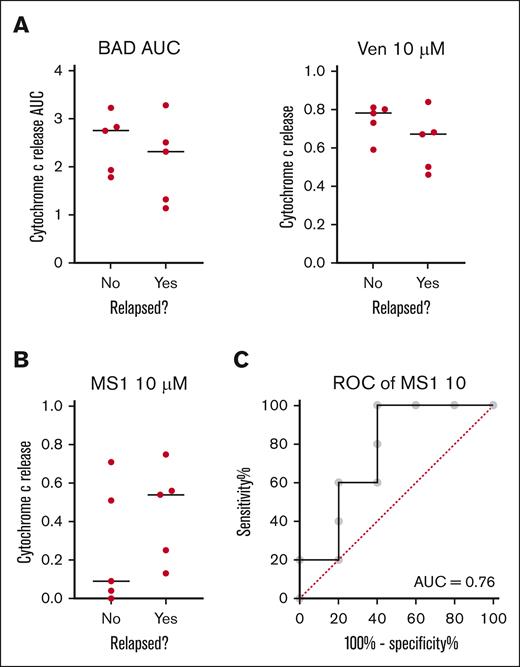

BH3 profiling

We have previously reported in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) that BH3 profiling of pretreatment myeloblasts predicts clinical response to venetoclax.30,31 Because response rates were so high, we asked whether BH3 profiling could predict relapse among patients who achieved CR using 10 pretreatment samples. The most significant predictor of response was the identification of MCL-1 dependence by the MS1 peptide in lymphoblasts (Figure 3). This is consistent with the results in AML, in which the identification of dependence on antiapoptotic proteins not targeted by venetoclax was the best predictor of poor clinical response.

BH3 profiling of pretreatment samples from patients with ALL. (A) Mitochondrial response to BAD BH3 (P = .27; 1-tailed t test) or venetoclax (P = .16) are not significant predictors of relapse. (B) Mitochondrial response to the MS1 peptide is the best BH3 profiling predictor of relapse (P = .11). (C) Receiver operator curve (ROC) for 10 μM MS1 as a binary predictor of relapse on venetoclax-based therapy (P = .18; AUC = 0.76). Black line indicates median. Each dot represents an individual patient. AUC, area under the curve.

BH3 profiling of pretreatment samples from patients with ALL. (A) Mitochondrial response to BAD BH3 (P = .27; 1-tailed t test) or venetoclax (P = .16) are not significant predictors of relapse. (B) Mitochondrial response to the MS1 peptide is the best BH3 profiling predictor of relapse (P = .11). (C) Receiver operator curve (ROC) for 10 μM MS1 as a binary predictor of relapse on venetoclax-based therapy (P = .18; AUC = 0.76). Black line indicates median. Each dot represents an individual patient. AUC, area under the curve.

CyTOF analysis of baseline and posttreatment samples

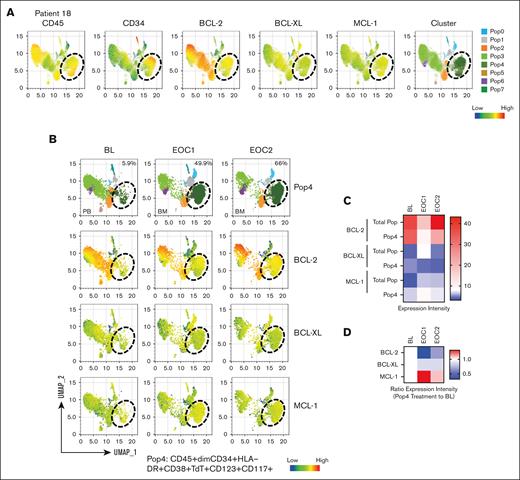

CyTOF analysis of 10 baseline samples from 6 responders and 3 nonresponders showed universally high BCL-2 levels and a trend toward higher expression of MCL-1 and p-STAT3 in CD45+low and CD45+low/CD34+ blast cells in nonresponders (supplemental Figure 1). Analysis of samples from 2 nonresponders with T-ALL (patients 18 and 13) showed expansion of the subpopulations Pop4 in patient 18 and Pop0 in patient 13 in samples collected at the end of cycle (EOC1) and 2 (EOC2); Pop4: BL vs EOC1 vs EOC2, 5.9% vs 49.9% vs 66%; Pop0: 3.8% vs 84.4% vs 46.8%. Immunophenotyping showed that these expanded populations are positive for CD34, HLA-DR, CD38, and TdT (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figures 2 and 3A-B). In patient 18, MCL-1–expressing Pop4 persisted on therapy with progressive increased MCL-1 levels but reduced BCL-2 and BCL-XL levels (Figure 4C-D). Conversely, in patient 13, Pop0 displayed increased levels of both BCL-XL and BCL-2, and reduced MCL-1 upon progression at EOC1 and EOC2 (supplemental Figure 3C-D). These findings, albeit preliminary, indicate that prosurvival codependency on MCL-1 or BCL-XL is associated with lack of response to venetoclax-based therapies.

High-dimensional CyTOF analysis of serial bone marrow samples in nonresponder patient 18. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection plots display the expression of CD45, CD34, BCL-2, BCL-XL, MCL-1, and clustering. (B) The percentages of persistent blast subpopulation (Pop4) and the expression of BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 at the indicated time points. (C) Heat map displays the expression level of BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 in Pop4 and in total population (Total Pop). (D) Expression ratio of EOC1 and EOC2 to baseline (BL) in Pop4.

High-dimensional CyTOF analysis of serial bone marrow samples in nonresponder patient 18. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection plots display the expression of CD45, CD34, BCL-2, BCL-XL, MCL-1, and clustering. (B) The percentages of persistent blast subpopulation (Pop4) and the expression of BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 at the indicated time points. (C) Heat map displays the expression level of BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 in Pop4 and in total population (Total Pop). (D) Expression ratio of EOC1 and EOC2 to baseline (BL) in Pop4.

Discussion

Our phase 1 multicenter trial establishes venetoclax plus attenuated chemotherapy (mini-HCVD) as a well-tolerated regimen for adults with high-risk ALL. Notably, there was no hepatotoxicity, a frequent barrier to treating adults with conventional chemotherapy or asparaginase- and/or inotuzumab-containing regimens.3,9,25,32 In addition, we did not encounter prolonged cytopenias, allowing treatment to be delivered with a median of 30 days between chemotherapy cycles. This contrasts with venetoclax-based regimens for AML,33 and inotuzumab-based approaches for ALL9,25 in which prolonged cytopenias frequently necessitate treatment delays. The reasons for this are not definitively known but we hypothesize that elderly patients with AML treated with venetoclax plus azacitidine often have mutations consistent with secondary ontogeny and therefore abnormal myeloid precursors leading to profound cytopenia. In patients with ALL, the underlying myeloid compartment is typically unaffected, leading to more robust myeloid regeneration. There is also impact on megakaryopoiesis as compared with inotuzumab ozogamicin.

The most common clinically significant toxicity was grade ≥3 infection, including febrile neutropenia, bacteremia, and pneumonia, despite common use of prophylactic antibiotics per standard practice at the recruiting institutions. Most infections occurred in patients with active disease during cycle 1, whereas the remainder of events occurred after remission was achieved. Notably, no patients experienced treatment-related mortality or discontinued study therapy because of treatment-related toxicity. This excellent tolerability was achieved with infrequent dose reductions and interruptions. Still, further improvements in safety, particularly to reduce the incidence of postremission infections requiring hospitalization, may be accomplished with modifications to this regimen being explored in the ongoing phase 2 extension of this study. These modifications include reduction in venetoclax dose (400 mg for 14 days per cycle) and decreasing the number of chemotherapy cycles.

Responses in patients with newly diagnosed ALL were very encouraging with 10 of 11 (90.9%) patients responding, all of whom achieved MRD-negative remissions by flow cytometry (sensitivity to <0.01%). Most studies of adults with Philadelphia chromosome–negative ALL report achievement in MRD negativity (<0.01%) of 40% to 60%, primarily with cohorts with median age far less than 60 years.34-37 These responses were particularly notable given the high-risk cohort with 6 of 11 patients having a hypodiploid karyotype associated with TP53 and 3 patients with therapy-related disease (prior treatment for multiple myeloma).

Importantly, 9 of 10 patients who achieved an MRD-negative remission were able to be consolidated with a reduced intensity HSCT and subsequently experience a durable remission. Of patients who received transplant, 4 are alive and in remission >4.5 years from study registration. Two patients died of complications of transplant without relapse whereas 3 patients relapsed late at 2.4 to 4.5 years from registration. Late relapses are known to be more likely to respond to salvage therapy. Among 3 patients with late relapse, 1 patient achieved a second CR after retreatment with venetoclax plus mini-HCVD, and another is in a second durable remission after treatment with brexucabtagene autoleucel.

In contrast, patients with R/R ALL in our study rarely responded to venetoclax plus mini-HCVD, with 2 of 3 achieved responses being quite brief. The R/R patients enrolled in this study were mostly T-lineage (5/8, including ETP), with high-risk genetics (6/8 with TP53 aberration), and heavily pretreated (all but 1 having received ≥2 previous lines of non-HSCT therapy, and prior HSCT in 5 of 8). These high-risk clinical features likely contributed to treatment resistance.

The very encouraging results seen in previously untreated patients in this study must be confirmed in a larger cohort and we are thus conducting a larger phase 2 study of newly diagnosed older adults (aged ≥55 years, or aged ≥50 years with elevated body mass index) with venetoclax plus mini-HCVD. There was initial concern that venetoclax might be associated with clinical tumor lysis syndrome. With appropriate prophylaxis for tumor lysis syndrome, this was not seen in any patient in the phase 1 study. Therefore, the phase 2 includes a faster venetoclax ramp-up (over 3 days). This allows earlier initiation of chemotherapy. Additionally, given no ascertainable differences in outcomes between patients treated with 400 vs 600 mg daily, we chose the 400 mg daily dose of venetoclax for the phase 2 study and we are administering venetoclax for only 14 days per cycle after achievement of CR. Finally, in recognition of the promising results of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 1910 study, which demonstrated improved survival and decreased toxicity in adults who received blinatumomab consolidation after chemotherapy,12 the phase 2 study has been amended to introduce 4 cycles of blinatumomab consolidation for patients with B-ALL after up to 4 cycles of venetoclax mini-HCVD (only 2 for patients aged ≥70 years). It is hoped that these modifications will further improve both safety and efficacy of this regimen.

We note excellent outcomes among our patients with newly diagnosed ALL who underwent reduced intensity HSCT consolidation, even without blinatumomab. There was a high rate of transplantation in our cohort based on frequent occurrence of high-risk features among enrolled patients. Further study will be needed to determine in which patients this venetoclax-based regimen, with incorporation of blinatumomab for patients with B-ALL, will be able to offer durable remissions in the absence of HSCT and in which high-risk eligible patients transplantation (which was feasible in our older adult cohort) should remain a priority.

Our study is notably limited by its small sample size and heterogenous population of patients with newly diagnosed and R/R B- and T-ALL. Studying this regimen prospectively in a larger cohort of patients with newly diagnosed ALL will also allow us to further characterize the toxicity and, especially, the efficacy of this regimen in different ALL subgroups. With a larger sample size, we will be able to study outcomes in different patient subgroups including those aged ≥70 years, and patients with specific disease features defined immunophenotypically (ie, ETP ALL) and genetically. Notably, in the phase 1 there were no patients with a KMT2A rearrangement or Philadelphia chromosome–like ALL; the performance of this regimen in those important subgroups requires additional study. Additionally, because the majority of responding patients bridged successfully to HSCT, further study of safety and efficacy of venetoclax in combination with POMP maintenance is needed.

Preliminary correlative findings identified dependence or expression of additional antiapoptotic proteins MCL-1 and BCL-XL in blasts from nonresponders. We also plan to conduct further correlative studies, to understand mechanisms of resistance and explore our ability to define high-risk subsets who may be better served by other approaches including broader targeting of the apoptotic pathway.38

In summary, venetoclax plus mini-HCVD chemotherapy is a well-tolerated regimen for adult patients with ALL, and with promising efficacy for treatment of newly diagnosed ALL in older adults, particularly when used as a bridge to reduced-intensity HSCT.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (grant 6486-16) and AbbVie who supported this work.

Authorship

Contribution: M.K., N.J., and D.J.D. conceived of and designed the study; M.R.L., S.S., J.K., Y.F., Z.Z., J.R., and K.S. analyzed the data; M.R.L. wrote the manuscript; J.R., A.L., Z.Z., and M.K. conducted correlative science; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.R.L. reports institutional research support from Novartis and AbbVie, and consulting/advisory roles with Novartis, Pfizer, Kite, and Jazz. E.S.W. reports a consulting/advisory role with and institutional research support from Curis. J.S.G. reports consulting/advisory roles with AbbVie, Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Servier, and institutional research support from AbbVie, Genentech, New Wave, Prelude, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. R.M.S. reports institutional research support from AbbVie, Syndax, and Janssen; reports consulting/advisory roles with AbbVie, Amgen, AvenCell, BerGen Bio, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellarity, CTI BioPharma, Curis Oncology, Daiichi Sankyo, Epizyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Hermavant, Jazz, Kura Oncology, Lava Therapeutics, Ligand Pharma, Redona Therapeutics, and Rigel; and serves on the data and safety monitoring boards of Aptevo, Epizyme, Syntrix, and Takeda. E.J. reports research grants from, and consultancies with, AbbVie, Amgen, Pfizer, Takeda, Autolus, and Kite. J.R. reports a consulting role with Zentalis. A.L. reports serving on the advisory boards of Zentalis Pharmaceuticals and Flash Therapeutics, and his employer, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, owns a patent portfolio around BH3 profiling. M.K. reports research funding from AbbVie, Allogene, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Gilead, ImmunoGen, MEI Pharma, Precision, Rafael, Sanofi, and Stemline; reports advisory/consulting roles with AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Auxenion, Bakx, Boehringer, Dark Blue Therapeutics, F. Hoffman La-Roche, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Legend, MEI Pharma, Redona, Sanofi, Sellas, Stemline, and Vincerx; holds stock options in/receives royalties from Reata Pharmaceuticals (intellectual property); and reports a patent with Novartis, Eli Lilly, and Reata Pharmaceuticals. N.J. reports research funding from Pharmacyclics, AbbVie, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, ADC Therapeutics, Cellectis, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Precision Biosciences, Fate Therapeutics, Kite/Gilead, MingSight, Takeda, Medisix, Loxo Oncology, Novalgen, Dialectic Therapeutics, Newave, Novartis, Carna Biosciences, Sana Biotechnology, and Kisoji Biotechnology, and advisory board membership/honoraria from Pharmacyclics, Janssen, AbbVie, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Kite/Gilead, Precision Biosciences, Loxo Oncology, BeiGene, Cellectis, MEI Pharma, Ipsen, CareDx, MingSight, Autolus, and Novalgen. D.J.D. reports consulting roles with Amgen, Autolus, Blueprint, Gilead, Jazz, Novartis, Pfizer, Servier, and Takeda, and grant/research funding from AbbVie, Novartis, Blueprint, and GlycoMimetics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marlise R. Luskin, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Dana 2056, Boston, MA 02215; email: marlise_luskin@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

N.J. and D.J.D. contributed equally to this study.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Marlise R. Luskin (marlise_luskin@dfci.harvard.edu). The data are not publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.