Key Points

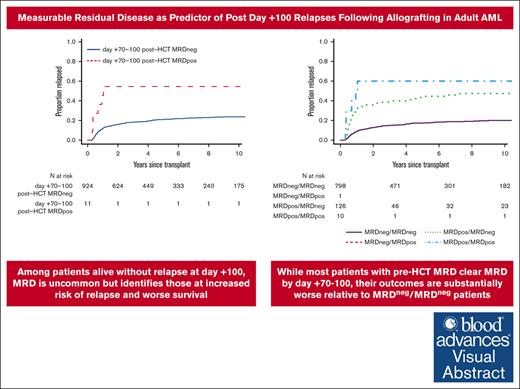

Among patients alive without relapse at day +100, MRD is uncommon but identifies those at increased risk of relapse and worse survival.

Most patients with pre-HCT MRD clear MRD by day +70 to +100 but outcomes are substantially worse relative to MRDneg/MRDneg patients.

Visual Abstract

Measurable residual disease (MRD) by multiparametric flow cytometry (MFC) before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) identifies patients at high risk of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) relapse, often occurring early after allografting. To examine the role of MFC MRD testing to predict later relapses, we examined 935 adults with AML or myelodysplastic neoplasm/AML transplanted in first or second morphologic remission who underwent bone marrow restaging studies between day 70 and 100 after HCT and were alive and without relapse by day +100. Of 935 adults, 136 (15%) had MRD before HCT, whereas only 11 (1%) had MRD at day +70 to +100. In day +100 landmark analyses, pre-HCT and day +70 to +100 MFC MRD were both associated with relapse (both P < .001), relapse-free survival (RFS; both P < .001) overall survival (OS; both P < .001), and, for post-HCT MRD, nonrelapse mortality (P = .001) after multivariable adjustment. Importantly, although 126/136 patients (92%) with MRD before HCT tested negative for MRD at day +70 to +100, their outcomes were inferior to those without MRD before HCT and at day +70 to +100, with 3-year relapse risk of 40% vs 15% (P < .001), 3-year RFS of 50% vs 72% (P < .001), and 3-year OS of 56% vs 76% (P < .001), whereas 3-year nonrelapse mortality estimates were similar (P = .53). Thus, despite high MRD conversion rates, outcomes MRD positive/MRD negative (MRDneg) patients are inferior to those of MRDneg/MRDneg patients, suggesting all patients with pre-HCT MRD should be considered for preemptive therapies after allografting.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) remains important as curative-intent treatment for many adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who have achieved a morphologic remission with lower- or higher-intensity chemotherapy.1 Still, AML recurrence after allografting is common and, nowadays, constitutes the major cause of HCT failure. Many factors have been associated with post-HCT relapse. Central among these is measurable residual disease (MRD), with an increasing number of studies demonstrating that MRD before or early after allografting identifies a subset of patients at particularly high risk of relapse and poor survival.2-5 However, a large proportion of the relapses, particularly among patients with MRD before or early after HCT, occur relatively early (eg, within the first 3 months) after allografting.6 So far, risk factors for relapses occurring at later time points (eg, after the first 3 months after allografting) are poorly characterized, and it is unclear what role pre- and early post-HCT MRD testing plays in the identification of patients at risk of experiencing such relapses. Because multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC)–based MRD testing is routine before, as well as ∼1 month and 3 months after, HCT at our institution, we examined this question in a large cohort of adults who underwent allogeneic HCT for AML or myelodysplastic neoplasm (MDS)/AML in first or second morphologic remission between 2006 and 2023.

Patients and methods

Study cohort

Using an electronic database, 1266 adults aged ≥18 years with AML or MDS/AML (2022 International Consensus Classification criteria7) were identified who received a first allograft while in first or second complete morphologic remission (ie, <5% blasts in bone marrow) between April 2006 and March 2023, agreed to their data being used for research purposes, and underwent MRD testing at our institution during the pre-HCT workup. Partial results from 1033 of these patients have been reported in recent publications.6,8-15 The HCT-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI) was calculated as previously described.16 Donors were selected by high-resolution HLA-typing. Post-HCT maintenance therapy was not typically done except with hypomethylating agents in a small subset of patients and in some patients with FLT3- or IDH-mutated AML after appropriate small-molecule inhibitors became available. Information on post-HCT outcomes was captured via the long-term follow-up program through medical records from our outpatient clinic and local clinics that provided primary care for patients in addition to records obtained on patients on research studies. All patients were treated on institutional review board–approved research protocols (all registered with ClinicalTrials.gov) or standard treatment protocols and gave consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Follow-up was current as of 30 July 2024.

Classification of disease risk and treatment response

The 2022 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) criteria1 were used to categorize cytogenetic disease risk at diagnosis. Because molecular data at time of diagnosis were lacking in many patients, only the cytogenetic component of the risk classification was used for categorization. Cytogenetically normal AML was assumed in patients with a normal karyotype even if <20 metaphases were available for analysis.6,10,11,14,17-19 Secondary AML was defined using the 2022 ELN criteria.1 Treatment responses were categorized as proposed by the ELN1 except that post-HCT relapse was defined as reemergence of >5% blasts by morphology or MFC in the blood or bone marrow, emergence of cytogenetic abnormalities seen previously, or presence/emergence of any level of disease if leading to a therapeutic intervention. Peripheral blood CD3 chimerism data were categorized as done previously.6,20 Decreasing CD3 chimerism was defined as an absolute decrease of donor CD3 peripheral blood chimerism of ≥20% between day +20 to +40 and day +70 to +100.21

Types and intensity of conditioning regimens

Regimens including high-dose fractionated total body irradiation (TBI; ≥12 Gy) with or without cyclophosphamide or fludarabine (FLU), high-dose TBI/thiotepa/FLU, busulfan (4 days) with cyclophosphamide or FLU, treosulfan/FLU with or without low-dose TBI, or any regimen containing a radiolabeled antibody, all of which targeting CD45, were considered myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimens. All others were considered non-MAC regimens.

MFC-based MRD testing

Ten-color MFC was performed as a routine clinical test on bone marrow aspirates obtained before starting conditioning therapy as well as ∼1 month and 3 months after HCT. This testing includes a panel of 3 antibody combinations, with up to 1 million events per tube collected and analyzed.6,12,22,23 MRD was identified by visual inspection via “different-from-normal approach” as a cell population showing deviation (typically seen in >1 antigen) from the normal patterns of antigen expression found on specific cell lineages at specific stages of maturation as compared with either normal or regenerating marrow based on the tested antibody panel. The sensitivity of the MFC MRD assay varies with the type of phenotypic aberrancy and immunophenotypes of normal cells in the background populations. Therefore, the MRD assay does not have uniform sensitivity across all cases but is able to detect MRD when present in most cases down to a level of 0.1% and in progressively smaller subsets of patients as the level of residual disease decreases below that level. The abnormal population was quantified as a percentage of the total CD45+ white cell events. As described before,6 the MRD assay methodology has remained essentially unchanged throughout the study period, with stable assay performance over time. As done in previous analyses,6,12,22,23 and in line with the performance characteristics of the assay,12 any detectable MRD was considered positive.

Statistical analysis

Unadjusted probabilities of relapse-free survival (RFS; events = relapse and death) and overall survival (OS; event = death) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and probabilities of relapse and nonrelapse mortality (NRM) were summarized using cumulative incidence estimates. NRM was defined as death without prior relapse and was considered a competing risk for relapse, whereas relapse was a competing risk for NRM. Day +100 landmark analyses for all outcomes were performed to assess their relationship with risk factors of interest. Associations with RFS and OS were assessed using Cox regression; cause-specific regression models were used for relapse and NRM. Besides pre- and/or post-HCT MFC MRD, covariates evaluated were: age at HCT, HCT-CI score (0-1 vs 2-3 vs ≥4), type of disease at diagnosis (de novo AML vs secondary AML vs MDS/AML), karyotype/cytogenetic risk group at diagnosis, first vs second remission at time of HCT, cytogenetics at time of HCT (normalized vs not normalized for patients presenting with abnormal karyotypes), conditioning intensity (MAC vs non-MAC), pre-HCT blood counts (recovered vs not recovered), stem cell source, HLA matching, graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis, and CD3 chimerism. Missing cytogenetic risk, karyotype, and CD3 chimerism data were accounted for as separate categories. C-statistics were estimated for multivariable models. The C-statistic was used to describe the ability of Cox and cause-specific regression models to predict outcomes. It is analogous to the area under the received operator characteristic curve used to describe prediction in the setting of binary outcomes. C-statistics have a range of 0.5 to 1, in which 0.5 is the C-statistic, meaning the model is no better at predicting outcome than random change (eg, a coin flip) and 1 is perfect prediction. C-statistics between 0.5 and 0.59 can be described as poor, 0.6-0.69 as fair, 0.7-0.79 as good, 0.8-0.89 as very good, and >0.9 as excellent. Categorical patient characteristics were compared using Fisher exact tests, and quantitative characteristics were compared with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Paired categorical data were compared using the McNemar test. For all analyses, 2-sided P values are reported, and values of <.05 were interpreted as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 18 (StataCorp; College Station, TX) and R (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Characteristics of study cohort

Among 1266 adults meeting the inclusion criteria for our retrospective study, 1115 (88%) had AML and 151 (12%) had MDS/AML. A total of 261 of 1266 patients (21%) tested positive for MRD during the pre-HCT evaluation (Table 1). Compared with 1005 patients without pre-HCT MRD, those with MRD before HCT had a higher risk of relapse (at 3 years: 61% [95% confidence interval [CI], 55-67] vs 23% [95% CI, 21-26]), lower RFS (at 3 years: 27% [95% CI, 22-33] vs 60% [95% CI, 57-63]), and lower OS (at 3 years: 36% [95% CI, 30-42] vs 65% [95% CI, 62-68]), consistent with our previous studies.6,8-14

Pre-HCT demographic and clinical characteristics of study population

| . | All patients (N = 1266) . | Day +100 cohort (n = 935) . |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at HCT (range), y | 57 (18-81) | 55 (18-77) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 588 (46) | 438 (47) |

| Disease, n (%) | ||

| All AML | 1115 (88) | 851 (91) |

| De novo AML | 870 (69) | 678 (73) |

| Secondary AML | 245 (19) | 173 (19) |

| MDS/AML | 151 (12) | 84 (9) |

| Cytogenetics at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Favorable | 75 (6) | 67 (7) |

| Intermediate | 810 (64) | 634 (68) |

| Adverse | 334 (26) | 201 (21) |

| Missing | 47 (4) | 33 (4) |

| Remission status at HCT, n (%) | ||

| First remission | 1009 (80) | 760 (81) |

| Second remission | 257 (20) | 175 (19) |

| Pre-HCT MRD by flow cytometry, n (%) | 261 (21) | 136 (15) |

| Cytogenetics before HCT, n (%) | ||

| Normalized karyotype | 472 (37) | 361 (39) |

| Abnormal karyotype | 236 (19) | 134 (14) |

| Noninformative data∗ | 558 (44) | 440 (47) |

| Recovered peripheral blood counts before HCT,† n (%) | 891 (70) | 677 (72) |

| HCT-CI score, n (%) | ||

| 0-1 | 483 (38) | 367 (39) |

| 2-3 | 425 (34) | 314 (34) |

| ≥4 | 344 (27) | 246 (26) |

| Missing | 14 (1) | 8 (1) |

| HLA matching, n (%) | ||

| 10/10 HLA-identical related donor | 288 (23) | 214 (23) |

| 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor | 633 (50) | 471 (50) |

| 1-2 allele/antigen-mismatched unrelated donor | 137 (11) | 99 (11) |

| HLA-haploidentical donor | 51 (4) | 37 (4) |

| Umbilical cord blood | 157 (12) | 114 (12) |

| Source of stem cells, n (%) | ||

| Peripheral blood | 1022 (81) | 762 (81) |

| Bone marrow | 87 (7) | 59 (6) |

| Umbilical cord blood | 157 (12) | 114 (12) |

| Conditioning intensity, n (%) | ||

| MAC | 734 (58) | 569 (61) |

| Non-MAC | 532 (42) | 366 (39) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | ||

| CNI + MMF w/wo sirolimus | 609 (48) | 418 (45) |

| CNI + MTX w/wo other | 457 (36) | 365 (39) |

| PTCy | 184 (15) | 139 (15) |

| Other | 16 (1) | 13 (1) |

| Post-HCT MRD status day +20 to +40, n (%) | ||

| MRDneg | 1123 (89) | 902 (96) |

| MRDpos | 99 (8) | 15 (2) |

| Not assessed | 44 (3) | 18 (2) |

| Post-HCT MRD status day +70 to +100, n (%) | ||

| MRDneg | 983 (78) | 924 (99) |

| MRDpos | 131 (10) | 11 (1) |

| Not assessed | 152 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics, n (%) | ||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 839 (66) | 798 (85) |

| MRDneg/MRDpos | 60 (5) | 1 (<1) |

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 144 (11) | 126 (13) |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 71 (6) | 10 (1) |

| Not assessed | 152 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Day +20-40/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics, n (%) | ||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 945 (75) | 897 (96) |

| MRDneg/MRDpos | 82 (6) | 5 (1) |

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 19 (2) | 9 (1) |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 48 (4) | 6 (1) |

| Not assessed | 172 (14) | 18 (2) |

| CD3 chimerism day +70 to +100, n (%) | ||

| Mixed (<95%) | 307 (24) | 240 (26) |

| Full (≥95%) | 565 (45) | 474 (51) |

| Not assessed | 394 (31) | 221 (24) |

| Decreasing CD3 chimerism day +20 to +40 to day +70 to +100, n (%) | ||

| No (increase or <20% decrease) | 689 (54) | 564 (60) |

| Yes (≥20 decrease) | 14 (1) | 8 (1) |

| Not assessed | 563 (44) | 363 (36) |

| . | All patients (N = 1266) . | Day +100 cohort (n = 935) . |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at HCT (range), y | 57 (18-81) | 55 (18-77) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 588 (46) | 438 (47) |

| Disease, n (%) | ||

| All AML | 1115 (88) | 851 (91) |

| De novo AML | 870 (69) | 678 (73) |

| Secondary AML | 245 (19) | 173 (19) |

| MDS/AML | 151 (12) | 84 (9) |

| Cytogenetics at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Favorable | 75 (6) | 67 (7) |

| Intermediate | 810 (64) | 634 (68) |

| Adverse | 334 (26) | 201 (21) |

| Missing | 47 (4) | 33 (4) |

| Remission status at HCT, n (%) | ||

| First remission | 1009 (80) | 760 (81) |

| Second remission | 257 (20) | 175 (19) |

| Pre-HCT MRD by flow cytometry, n (%) | 261 (21) | 136 (15) |

| Cytogenetics before HCT, n (%) | ||

| Normalized karyotype | 472 (37) | 361 (39) |

| Abnormal karyotype | 236 (19) | 134 (14) |

| Noninformative data∗ | 558 (44) | 440 (47) |

| Recovered peripheral blood counts before HCT,† n (%) | 891 (70) | 677 (72) |

| HCT-CI score, n (%) | ||

| 0-1 | 483 (38) | 367 (39) |

| 2-3 | 425 (34) | 314 (34) |

| ≥4 | 344 (27) | 246 (26) |

| Missing | 14 (1) | 8 (1) |

| HLA matching, n (%) | ||

| 10/10 HLA-identical related donor | 288 (23) | 214 (23) |

| 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor | 633 (50) | 471 (50) |

| 1-2 allele/antigen-mismatched unrelated donor | 137 (11) | 99 (11) |

| HLA-haploidentical donor | 51 (4) | 37 (4) |

| Umbilical cord blood | 157 (12) | 114 (12) |

| Source of stem cells, n (%) | ||

| Peripheral blood | 1022 (81) | 762 (81) |

| Bone marrow | 87 (7) | 59 (6) |

| Umbilical cord blood | 157 (12) | 114 (12) |

| Conditioning intensity, n (%) | ||

| MAC | 734 (58) | 569 (61) |

| Non-MAC | 532 (42) | 366 (39) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | ||

| CNI + MMF w/wo sirolimus | 609 (48) | 418 (45) |

| CNI + MTX w/wo other | 457 (36) | 365 (39) |

| PTCy | 184 (15) | 139 (15) |

| Other | 16 (1) | 13 (1) |

| Post-HCT MRD status day +20 to +40, n (%) | ||

| MRDneg | 1123 (89) | 902 (96) |

| MRDpos | 99 (8) | 15 (2) |

| Not assessed | 44 (3) | 18 (2) |

| Post-HCT MRD status day +70 to +100, n (%) | ||

| MRDneg | 983 (78) | 924 (99) |

| MRDpos | 131 (10) | 11 (1) |

| Not assessed | 152 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics, n (%) | ||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 839 (66) | 798 (85) |

| MRDneg/MRDpos | 60 (5) | 1 (<1) |

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 144 (11) | 126 (13) |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 71 (6) | 10 (1) |

| Not assessed | 152 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Day +20-40/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics, n (%) | ||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 945 (75) | 897 (96) |

| MRDneg/MRDpos | 82 (6) | 5 (1) |

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 19 (2) | 9 (1) |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 48 (4) | 6 (1) |

| Not assessed | 172 (14) | 18 (2) |

| CD3 chimerism day +70 to +100, n (%) | ||

| Mixed (<95%) | 307 (24) | 240 (26) |

| Full (≥95%) | 565 (45) | 474 (51) |

| Not assessed | 394 (31) | 221 (24) |

| Decreasing CD3 chimerism day +20 to +40 to day +70 to +100, n (%) | ||

| No (increase or <20% decrease) | 689 (54) | 564 (60) |

| Yes (≥20 decrease) | 14 (1) | 8 (1) |

| Not assessed | 563 (44) | 363 (36) |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; PTCy, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide; w/wo, with/without.

Normal cytogenetics in patient with cytogenetically normal disease or missing cytogenetics at diagnosis.

ANC ≥103/μL and platelets ≥105/μL.

Of 1266 patients, 206 (16%) experienced disease relapse before day +100 after allografting, and 89 (7%) died within the same time (33 [3%] after relapse, and 56 [4%] without prior relapse). Relapse before day +100 after allografting was more common among patients with pre-HCT MRD than those without (day-100 cumulative incidence: 38% [95% CI, 32-44] vs 11% [95% CI, 9-13]; P < .001), as was death (day-100 cumulative incidence: 12% [95% CI, 8-15] vs 6% [95% CI, 4-7]; P = .003). In contrast, the likelihood of NRM before day +100 was relatively similar for patients with and those without pre-HCT MRD (day-100 cumulative incidence: 5% [95% CI, 3-8] vs 4% [95% CI, 3-6]; P = .51).

Factors associated with outcome in day +100 landmark analysis

Of 1266 patients, 263 (21%) experienced relapse of their myeloid neoplasm and/or died before day +100 after allografting; 1 additional patient was censored without relapse or death before day +100. Of the remaining 1003 patients, 935 (93%) underwent bone marrow staging studies between days +70 and +100 after allografting; their patient- and disease-specific characteristics are summarized in Table 1. As a result of the higher likelihood of disease relapse and/or death before day +100 after allografting among patients who tested positive for MFC MRD during the pre-HCT workup, the proportion of patients with pre-HCT MRD was lower in the day +100 cohort than the entire study population (136/935 [15%] vs 261/1266 [21%], P < .001).

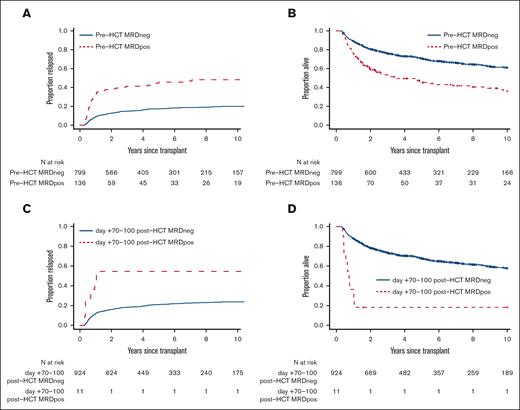

With a median follow-up of 74.0 months (range, 5.3-216.6) after HCT among survivors, there were 358 deaths, 202 relapses, and 187 NRM events contributing to the probability estimates for relapse, OS, RFS, and NRM in the 935 patients who underwent bone marrow restaging studies between days +70 and +100 and were alive and without relapse by day +100. In a first set of analyses in this cohort, we assessed the relationship between MRD status and post-HCT outcome in day +100 landmark analyses by using information from either the pre-HCT or the post-HCT MRD assay in an isolated fashion, that is, by not taking pre-/post-HCT MRD dynamics into account. As depicted in Figure 1 and Table 2, the 136 patients with pre-HCT MRD had substantially higher 3-year risk of relapse (41% [95% CI, 33-50] vs 15% [95% CI, 12-18]) and lower 3-year estimates of RFS (43% [95% CI, 35-52] vs 71% [95% CI, 68-75]) and OS (47% [95% CI, 39-56] vs 72% [95% CI, 69-75]) than 799 patients without MRD at the time of pre-HCT evaluation. Compared with pre-HCT MRD, post-HCT MRD was less common and only found in 11 of 935 (1%) patients. These 11 patients had significantly worse 3-year outcomes than the 924 who had no MRD at day +70 to +100 after allografting (relapse: 55% [95% CI, 18-81] vs 18% [95% CI, 16-21]; RFS: 9% [95% CI, 1-59] vs 69% [95% CI, 66-72]; OS: 18% [95% CI, 5-64] vs 73% [95% CI, 70-76]).

Post-HCT outcomes for 935 adults with AML undergoing allogeneic HCT while in first or second morphologic remission, stratified by pre- or post-HCT MRD status. Day +100 landmark analysis of (A,C) risk of relapse and (B,D) OS for the entire study cohort, stratified by (A,B) pre-HCT MFC MRD and (C,D) day +70 to +100 post-HCT MFC MRD, respectively.

Post-HCT outcomes for 935 adults with AML undergoing allogeneic HCT while in first or second morphologic remission, stratified by pre- or post-HCT MRD status. Day +100 landmark analysis of (A,C) risk of relapse and (B,D) OS for the entire study cohort, stratified by (A,B) pre-HCT MFC MRD and (C,D) day +70 to +100 post-HCT MFC MRD, respectively.

Outcome probabilities (with 95% CI) at 3 years, stratified by conditioning intensity and pre- and/or post-HCT MRD status or MRD dynamics

| . | Cumulative incidence of relapse at 3 y . | RFS at 3 y . | OS at 3 y . | Cumulative incidence of NRM at 3 y . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (N = 935) | 19% (16%-21%) | 68% (65%-71%) | 73% (70%-76%) | 13% (11%-15%) |

| Pre-HCT MRD information only | ||||

| MRDneg (n = 799) | 15% (12%-18%) | 72% (69%-75%) | 76% (73%-79%) | 13% (11%-16%) |

| MRDpos (n = 136) | 41% (33%-50%) | 47% (39%-56%) | 53% (45%-63%) | 12% (7%-18%) |

| Day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD information only | ||||

| MRDneg (n = 924) | 18% (15%-21%) | 69% (66%-72%) | 73% (70%-76%) | 13% (11%-15%) |

| MRDpos (n = 11) | 55% (18%-81%) | 9% (1%-59%) | 18% (5%-64%) | 36% (10%-65%) |

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD information | ||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg (n = 798) | 15% (13%-18%) | 72% (69%-75%) | 76% (73%-79%) | 13% (11%-16%) |

| MRDneg/MRDpos (n = 1) | - | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| MRDpos/MRDneg (n = 126) | 40% (31%-49%) | 50% (41%-59%) | 56% (48%-66%) | 11% (6%-17%) |

| MRDpos/MRDpos (n = 10) | 60% (20%-85%) | 10% (2%-64%) | 13% (6%-69%) | 30% (6%-60%) |

| Day +20 o +40/day +70 to +100 MRD information | ||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg (n = 897) | 18% (16%-21%) | 70% (67%-73%) | 74% (72%-77%) | 12% (10%-14%) |

| MRDneg/MRDpos (n = 5) | 60% (15%-95%) | 0% | 0% | 40% (5%-85%) |

| MRDpos/MRDneg (n = 9) | 22% (3%-53%) | 40% (17%-94%) | 35% (12%-98%) | 38% (7%-701%) |

| MRDpos/MRDpos (n = 6) | 67% (10%-93%) | 17% (3%-100%) | 19% (11%-100%) | 17% (1%-56%) |

| . | Cumulative incidence of relapse at 3 y . | RFS at 3 y . | OS at 3 y . | Cumulative incidence of NRM at 3 y . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (N = 935) | 19% (16%-21%) | 68% (65%-71%) | 73% (70%-76%) | 13% (11%-15%) |

| Pre-HCT MRD information only | ||||

| MRDneg (n = 799) | 15% (12%-18%) | 72% (69%-75%) | 76% (73%-79%) | 13% (11%-16%) |

| MRDpos (n = 136) | 41% (33%-50%) | 47% (39%-56%) | 53% (45%-63%) | 12% (7%-18%) |

| Day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD information only | ||||

| MRDneg (n = 924) | 18% (15%-21%) | 69% (66%-72%) | 73% (70%-76%) | 13% (11%-15%) |

| MRDpos (n = 11) | 55% (18%-81%) | 9% (1%-59%) | 18% (5%-64%) | 36% (10%-65%) |

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD information | ||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg (n = 798) | 15% (13%-18%) | 72% (69%-75%) | 76% (73%-79%) | 13% (11%-16%) |

| MRDneg/MRDpos (n = 1) | - | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| MRDpos/MRDneg (n = 126) | 40% (31%-49%) | 50% (41%-59%) | 56% (48%-66%) | 11% (6%-17%) |

| MRDpos/MRDpos (n = 10) | 60% (20%-85%) | 10% (2%-64%) | 13% (6%-69%) | 30% (6%-60%) |

| Day +20 o +40/day +70 to +100 MRD information | ||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg (n = 897) | 18% (16%-21%) | 70% (67%-73%) | 74% (72%-77%) | 12% (10%-14%) |

| MRDneg/MRDpos (n = 5) | 60% (15%-95%) | 0% | 0% | 40% (5%-85%) |

| MRDpos/MRDneg (n = 9) | 22% (3%-53%) | 40% (17%-94%) | 35% (12%-98%) | 38% (7%-701%) |

| MRDpos/MRDpos (n = 6) | 67% (10%-93%) | 17% (3%-100%) | 19% (11%-100%) | 17% (1%-56%) |

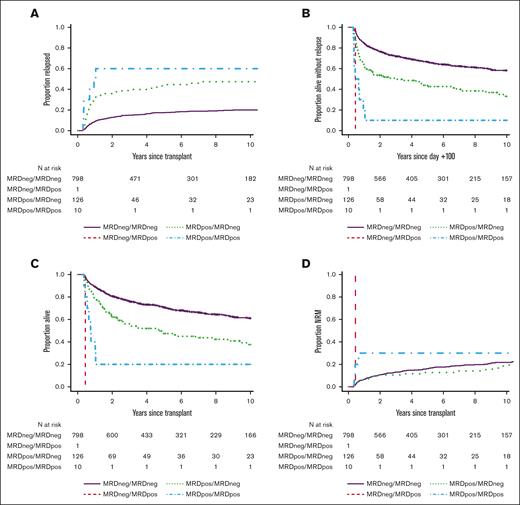

The uncommon occurrence of MRD at day +70 to +100 indicated most patients with pre-HCT MRD clear their evidence of residual disease over the first 3 months after allografting. Indeed, of 136 patients with pre-HCT MRD, 126 (92%) converted to MRD negativity at day +70 to +100, whereas 10 remained MRD positive (MRDpos); only 1 patient without pre-HCT MRD had a positive MRD test at day +70 to +100. Patients who were MRD negative (MRDneg)/MRDneg (pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics) had the best outcomes, with 3-year RFS and OS estimates of 72% (95% CI, 69-75) and 76% (95% CI, 73-79), respectively, and a risk of relapse of 15% (95% CI, 13-17) at 3-years (Table 2; Figure 2). In contrast, 3-year RFS, OS, and relapse estimates were 10% (95% CI, 2-64), 20% (95% CI, 6-69), and 30% (95% CI, 6-60) for patients who were MRDpos/MRDpos. Three-year outcome estimates for the patients who were MRDpos/MRDneg were in between those of patients who were MRDneg/MRDneg and those who were MRDpos/MRDpos (RFS: 49% [95% CI, 41-59]; OS: 56% [95% CI, 48-66]; relapse: 31% [95% CI, 6-17]).

Post-HCT outcomes for 935 adults with AML undergoing allogeneic HCT while in first or second morphologic remission, stratified by pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics. Day +100 landmark analysis of (A) risk of relapse, (B) RFS, (C) OS, and (D) risk of NRM, shown for the entire study cohort.

Post-HCT outcomes for 935 adults with AML undergoing allogeneic HCT while in first or second morphologic remission, stratified by pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics. Day +100 landmark analysis of (A) risk of relapse, (B) RFS, (C) OS, and (D) risk of NRM, shown for the entire study cohort.

We then evaluated both univariable and multivariable regression models for the end points of relapse, RFS, OS, and NRM, accounting for the covariates noted in “Patients and methods,” to study the relationship between pre- and/or post-HCT MRD status and post-HCT outcomes in more detail. As summarized in Table 3, univariate models showed that having MRD before HCT was associated with higher risk of relapse, lower RFS, and lower OS compared with not having pre-HCT MRD (all P < .001). Likewise, MRD detectable at day +70 to +100 after HCT was associated with higher risk of relapse, lower RFS, and lower OS relative to not having MRD (all P < .001). Like single- point data from MRD testing, data from serial MRD testing were also significantly associated with relapse risk and survival. Specifically, when considering both results from pre-HCT MRD and day +70 to +100 MRD, patients who were MRDpos/MRDneg and those who were MRDpos/MRDpos had higher risks of relapse, lower RFS, and lower OS compared with patients who were MRDneg/MRDneg, with those outcomes being worst in patients who were MRDpos/MRDpos and risks of those who were MRDpos/MRDneg being between those of patients who were MRDneg/MRDneg and those who were MRDpos/MRDpos, respectively. Qualitatively similar results were obtained when considering results from day +20 to +40 MRD and day +70 to +100 MRD testing (Table 3). Besides pre- and/or post-HCT MFC MRD, several other patient-, disease-, and HCT-related characteristics were also associated with either relapse, RFS, OS, and/or NRM, including age, HCT-CI score, disease type, cytogenetic disease risk, remission number, residual cytogenetic abnormalities, conditioning intensity, pre-HCT blood counts, HLA disparity, and type of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis, but not CD3 chimerism (Table 3).

Univariate regression models of day +100 study cohort

| . | Risk of relapse . | Risk of relapse/death . | Risk of death . | Risk of NRM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Pre-HCT MRD (vs no pre-HCT MRD) | 3.38 (2.50-4.57) | <.001 | 2.25 (1.77-2.86) | <.001 | 2.08 (1.62-2.66) | <.001 | 1.24 (0.81-1.89) | .32 |

| Day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD | 5.19 (3.18-16.28) | <.001 | 5.68 (3.01-10.70) | <.001 | 5.22 (2.68-10.17) | <.001 | 4.28 (1.57-11.63) | .0044 |

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDneg/MRDpos | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 3.16 (2.31-4.32) | <.001 | 2.10 (1.64-2.70) | <.001 | 1.96 (1.51-2.53) | <.001 | 1.15 (0.74-1.80) | .54 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 9.37 (4.12-21.29) | <.001 | 5.90 (3.03-11.52) | <.001 | 5.27 (2.60-10.70) | <.001 | 3.32 (1.05-10.50) | .041 |

| Day +20 to +40/+70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDneg/MRDpos | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 1.98 (0.63-6.19) | .24 | 2.29 (1.02-5.13) | .0045 | 1.86 (0.77-4.49) | .17 | 2.73 (0.87-8.56) | .086 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 5.90 (2.19-15.91) | <.001 | 3.45 (1.42-8.37) | .0062 | 2.90 (1.08-7.80) | .035 | 1.28 (0.18-9.21) | .81 |

| Age at HCT (per 10 y) | 1.11 (1.03-1.19) | .0044 | 1.20 (1.14-1.27) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.15-1.30) | <.001 | 1.40 (1.27-1.55) | <.001 |

| HCT-CI score | ||||||||

| 0-1 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 2-3 | 1.07 (0.78-1.47) | .68 | 1.23 (0.97-1.57) | .084 | 1.27 (0.99-1.63) | .058 | 1.48 (1.03-2.13) | .033 |

| ≥4 | 0.96 (0.67-1.36) | .81 | 1.29 (1.00-1.65) | .046 | 1.34 (1.04-1.74) | .026 | 1.77 (1.23-2.55) | .002 |

| Disease type | ||||||||

| De novo AML | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Secondary AML | 1.38 (0.99-1.93) | .057 | 1.39 (1.09-1.77) | .007 | 1.42 (1.11-1.82) | .0059 | 1.41 (0.99-1.99) | .056 |

| MDS/AML | 1.05 (0.63-1.74) | .85 | 1.31 (0.94-1.83) | .11 | 1.42 (1.01-1.99) | .043 | 1.61 (1.03-2.52) | .036 |

| Cytogenetic risk | ||||||||

| Favorable | 0.56 (0.28-1.15) | .12 | 0.71 (0.46-1.10) | .13 | 0.71 (0.45-1.12) | .14 | 0.83 (0.48-1.45) | .52 |

| Intermediate | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Adverse | 1.75 (1.29-2.38) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.00-1.59) | .052 | 1.21 (0.95-1.55) | .12 | 0.83 (0.57-1.21) | .33 |

| Second remission (vs first remission) | 0.95 (0.67-1.35) | .77 | 0.99 (0.77-1.27) | .91 | 1.04 (0.80-1.34) | .78 | 1.03 (0.72-1.47) | .88 |

| Pre-HCT karyotype | ||||||||

| Normalized | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Not normalized | 1.64 (1.11-2.41) | .013 | 1.51 (1.12-2.02) | .0062 | 1.60 (1.18-2.17) | .0022 | 1.35 (0.86-2.11) | .19 |

| Non-MAC regimen (vs MAC) | 1.00 (0.75-1.33) | 1.00 | 1.70 (1.39-2.08) | <.001 | 1.86 (1.51-2.30) | <.001 | 3.02 (2.25-4.06) | <.001 |

| Not recovered pre-HCT blood counts∗ | 1.25 (0.93-1.68) | .14 | 1.32 (1.06-1.63) | .012 | 1.32 (1.05-1.65) | .016 | 1.39 (1.02-1.90) | .036 |

| Stem cell source | ||||||||

| Peripheral blood | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Bone marrow | 1.29 (0.79-2.09) | .31 | 0.89 (0.60-1.32) | .56 | 0.82 (0.55-1.24) | .35 | 0.55 (0.28-1.07) | .078 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 0.73 (0.40-1.17) | .20 | 0.77 (0.55-1.08) | .13 | 0.79 (0.55-1.12) | .18 | 0.82 (0.51-1.32) | .41 |

| HLA matching | ||||||||

| 10/10 HLA-identical related donor | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor | 0.86 (0.61-1.20) | .38 | 0.99 (0.77-1.27) | .93 | 1.00 (0.77-1.29) | .98 | 1.15 (0.80-1.67) | .45 |

| 1-2 allele/antigen-mismatched donor | 1.14 (0.70-1.85) | .60 | 1.64 (1.18-2.28) | .003 | 1.75 (1.25-2.45) | .0012 | 2.34 (1.48-3.68) | <.001 |

| HLA-haploidentical donor | 1.75 (0.94-3.29) | .08 | 1.61 (0.96-2.71) | .072 | 1.49 (0.86-2.58) | .16 | 1.27 (0.50-3.23) | .61 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 0.68 (0.40-1.17) | .17 | 0.84 (0.58-1.23) | .38 | 0.87 (0.59-1.30) | .50 | 1.06 (0.61-1.82) | .84 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||

| CNI + MMF w/wo sirolimus | 1.06 (0.79-1.44) | .69 | 1.52 (1.23-1.89) | <.001 | 1.69 (1.34-2.12) | <.001 | 2.21 (1.61-3.03) | <.001 |

| CNI + MTX w/wo other | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| PTCy | 1.26 (0.84-1.90) | .26 | 1.16 (0.83-1.62) | .38 | 1.20 (0.84-1.71) | .31 | 0.93 (0.51-1.67) | .80 |

| CD3 chimerism at day +70 to +100 | ||||||||

| Mixed (<95%) | 0.99 (0.71-1.38) | .96 | 1.12 (0.89-1.40) | .35 | 1.12 (0.88-1.42) | .36 | 1.25 (0.91-1.73) | .17 |

| Full (≥95%) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Decreasing CD3 chimerism | ||||||||

| No (increase or <20% decrease) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Yes (≥20% decrease) | 0.44 (0.06-3.17) | .42 | 0.63 (0.20-1.96) | .42 | 0.68 (0.22-2.13) | .51 | 0.79 (0.19-3.19) | .74 |

| . | Risk of relapse . | Risk of relapse/death . | Risk of death . | Risk of NRM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Pre-HCT MRD (vs no pre-HCT MRD) | 3.38 (2.50-4.57) | <.001 | 2.25 (1.77-2.86) | <.001 | 2.08 (1.62-2.66) | <.001 | 1.24 (0.81-1.89) | .32 |

| Day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD | 5.19 (3.18-16.28) | <.001 | 5.68 (3.01-10.70) | <.001 | 5.22 (2.68-10.17) | <.001 | 4.28 (1.57-11.63) | .0044 |

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDneg/MRDpos | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 3.16 (2.31-4.32) | <.001 | 2.10 (1.64-2.70) | <.001 | 1.96 (1.51-2.53) | <.001 | 1.15 (0.74-1.80) | .54 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 9.37 (4.12-21.29) | <.001 | 5.90 (3.03-11.52) | <.001 | 5.27 (2.60-10.70) | <.001 | 3.32 (1.05-10.50) | .041 |

| Day +20 to +40/+70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDneg/MRDpos | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 1.98 (0.63-6.19) | .24 | 2.29 (1.02-5.13) | .0045 | 1.86 (0.77-4.49) | .17 | 2.73 (0.87-8.56) | .086 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 5.90 (2.19-15.91) | <.001 | 3.45 (1.42-8.37) | .0062 | 2.90 (1.08-7.80) | .035 | 1.28 (0.18-9.21) | .81 |

| Age at HCT (per 10 y) | 1.11 (1.03-1.19) | .0044 | 1.20 (1.14-1.27) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.15-1.30) | <.001 | 1.40 (1.27-1.55) | <.001 |

| HCT-CI score | ||||||||

| 0-1 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 2-3 | 1.07 (0.78-1.47) | .68 | 1.23 (0.97-1.57) | .084 | 1.27 (0.99-1.63) | .058 | 1.48 (1.03-2.13) | .033 |

| ≥4 | 0.96 (0.67-1.36) | .81 | 1.29 (1.00-1.65) | .046 | 1.34 (1.04-1.74) | .026 | 1.77 (1.23-2.55) | .002 |

| Disease type | ||||||||

| De novo AML | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Secondary AML | 1.38 (0.99-1.93) | .057 | 1.39 (1.09-1.77) | .007 | 1.42 (1.11-1.82) | .0059 | 1.41 (0.99-1.99) | .056 |

| MDS/AML | 1.05 (0.63-1.74) | .85 | 1.31 (0.94-1.83) | .11 | 1.42 (1.01-1.99) | .043 | 1.61 (1.03-2.52) | .036 |

| Cytogenetic risk | ||||||||

| Favorable | 0.56 (0.28-1.15) | .12 | 0.71 (0.46-1.10) | .13 | 0.71 (0.45-1.12) | .14 | 0.83 (0.48-1.45) | .52 |

| Intermediate | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Adverse | 1.75 (1.29-2.38) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.00-1.59) | .052 | 1.21 (0.95-1.55) | .12 | 0.83 (0.57-1.21) | .33 |

| Second remission (vs first remission) | 0.95 (0.67-1.35) | .77 | 0.99 (0.77-1.27) | .91 | 1.04 (0.80-1.34) | .78 | 1.03 (0.72-1.47) | .88 |

| Pre-HCT karyotype | ||||||||

| Normalized | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Not normalized | 1.64 (1.11-2.41) | .013 | 1.51 (1.12-2.02) | .0062 | 1.60 (1.18-2.17) | .0022 | 1.35 (0.86-2.11) | .19 |

| Non-MAC regimen (vs MAC) | 1.00 (0.75-1.33) | 1.00 | 1.70 (1.39-2.08) | <.001 | 1.86 (1.51-2.30) | <.001 | 3.02 (2.25-4.06) | <.001 |

| Not recovered pre-HCT blood counts∗ | 1.25 (0.93-1.68) | .14 | 1.32 (1.06-1.63) | .012 | 1.32 (1.05-1.65) | .016 | 1.39 (1.02-1.90) | .036 |

| Stem cell source | ||||||||

| Peripheral blood | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Bone marrow | 1.29 (0.79-2.09) | .31 | 0.89 (0.60-1.32) | .56 | 0.82 (0.55-1.24) | .35 | 0.55 (0.28-1.07) | .078 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 0.73 (0.40-1.17) | .20 | 0.77 (0.55-1.08) | .13 | 0.79 (0.55-1.12) | .18 | 0.82 (0.51-1.32) | .41 |

| HLA matching | ||||||||

| 10/10 HLA-identical related donor | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor | 0.86 (0.61-1.20) | .38 | 0.99 (0.77-1.27) | .93 | 1.00 (0.77-1.29) | .98 | 1.15 (0.80-1.67) | .45 |

| 1-2 allele/antigen-mismatched donor | 1.14 (0.70-1.85) | .60 | 1.64 (1.18-2.28) | .003 | 1.75 (1.25-2.45) | .0012 | 2.34 (1.48-3.68) | <.001 |

| HLA-haploidentical donor | 1.75 (0.94-3.29) | .08 | 1.61 (0.96-2.71) | .072 | 1.49 (0.86-2.58) | .16 | 1.27 (0.50-3.23) | .61 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 0.68 (0.40-1.17) | .17 | 0.84 (0.58-1.23) | .38 | 0.87 (0.59-1.30) | .50 | 1.06 (0.61-1.82) | .84 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||

| CNI + MMF w/wo sirolimus | 1.06 (0.79-1.44) | .69 | 1.52 (1.23-1.89) | <.001 | 1.69 (1.34-2.12) | <.001 | 2.21 (1.61-3.03) | <.001 |

| CNI + MTX w/wo other | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| PTCy | 1.26 (0.84-1.90) | .26 | 1.16 (0.83-1.62) | .38 | 1.20 (0.84-1.71) | .31 | 0.93 (0.51-1.67) | .80 |

| CD3 chimerism at day +70 to +100 | ||||||||

| Mixed (<95%) | 0.99 (0.71-1.38) | .96 | 1.12 (0.89-1.40) | .35 | 1.12 (0.88-1.42) | .36 | 1.25 (0.91-1.73) | .17 |

| Full (≥95%) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Decreasing CD3 chimerism | ||||||||

| No (increase or <20% decrease) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Yes (≥20% decrease) | 0.44 (0.06-3.17) | .42 | 0.63 (0.20-1.96) | .42 | 0.68 (0.22-2.13) | .51 | 0.79 (0.19-3.19) | .74 |

Abbreviations are explained in Table 1.

Recovered: ANC ≥ 103/μL and platelets ≥ 105/μL; not recovered: ANC < 103/μL and/or platelets < 105/μL.

After multivariable adjustment, pre-HCT MRD remained statistically significantly associated with a higher risk of relapse (hazard ratio [HR], 3.31; 95% CI, 2.36-4.62; P < .001) and inferior RFS (HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.64-2.78; P < .001) and OS (HR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.47-2.54; P < .001), whereas there was no significant difference in NRM risk (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.76-1.90; P = .43). By comparison, day +70 to 95% CI, 100 MRD remained statistically significantly associated with higher risk of relapse (HR, 5.43; 95% CI, 2.28-12.91; P < .001) and NRM (HR, 5.58; 95% CI, 1.90-16.35; P = .002) as well as inferior RFS (HR, 5.21; 95% CI, 2.64-10.22; P < .001) and OS (HR, 5.26; 95% CI, 2.59-10.67; P < .001). As summarized in Table 4, pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics were also independently associated with relapse and survival. Specifically, patients who were either MRDpos/MRDneg or MRDpos/MRDpos had higher risks of relapse, lower RFS, and lower OS compared with those who were MRDneg/MRDneg (all P < .001), with those outcomes being worst in patients who were MRDpos/MRDpos and risks of those who were MRDpos/MRDneg being between risks of those who were MRDneg/MRDneg and those who were MRDpos/MRDpos. However, the accuracy of the prediction models using information from pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics was essentially unchanged from the accuracy of models using information from pre-HCT MRD testing only (C-statistic for relapse: 0.68 for models with pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD dynamics vs 0.68 for models with pre-HCT data only; C-statistic for RFS: 0.64 vs 0.65; C-statistic for OS: 0.65 vs 0.66; C-statistic for NRM: 0.69 vs 0.69), and the accuracy of all models was only modest. In contrast to information from MRD testing, some of the other patient-, disease-, and HCT-related characteristics were no longer associated with any of these post-HCT outcomes after multivariable adjustment, including remission number, residual cytogenetic abnormalities, and pre-HCT blood counts.

Multivariable regression models of day +100 study cohort

| . | Risk of relapse . | Risk of relapse/death . | Risk of death . | Risk of NRM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 3.09 (2.19-4.38) | <.001 | 1.99 (1.51-2.62) | <.001 | 1.81 (1.36-2.40) | <.001 | 1.10 (0.68-1.78) | .71 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 7.66 (3.21-18.30) | <.001 | 5.80 (2.84-11.84) | <.001 | 5.57 (2.63-11.80) | <.001 | 4.70 (1.37-16.18) | .0014 |

| Age at HCT (per 10 y) | 0.97 (0.85-1.10) | .61 | 1.07 (0.97-1.18) | .18 | 1.09 (0.98-1.21) | .12 | 1.22 (1.04-1.44) | .013 |

| HCT-CI score | ||||||||

| 0-1 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 2-3 | 0.97 (0.70-1.36) | .88 | 1.17 (0.91-1.50) | .22 | 1.22 (0.94-1.58) | .14 | 1.45 (1.00-2.09) | .052 |

| ≥4 | 0.95 (0.65-1.38) | .78 | 1.21 (0.93-1.58) | .16 | 1.25 (0.95-1.66) | .11 | 1.59 (1.08-2.36) | .02 |

| Disease type | ||||||||

| De novo AML | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Secondary AML | 1.07 (0.74-1.55) | .72 | 1.06 (0.81-1.37) | .69 | 1.06 (0.80-1.40) | .68 | 1.05 (0.72-1.54) | .80 |

| MDS/AML | 0.66 (0.38-1.15) | .14 | 1.08 (0.75-1.55) | .68 | 1.21 (0.84-1.75) | .31 | 1.68 (1.03-2.72) | .036 |

| Cytogenetic risk | ||||||||

| Favorable | 0.67 (0.30-1.48) | .32 | 0.85 (0.52-1.40) | .52 | 0.83 (0.50-1.40) | .49 | 1.01 (0.53-1.91) | .98 |

| Intermediate | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Adverse | 1.71 (1.15-2.55) | .0085 | 1.22 (0.91-1.64) | .18 | 1.16 (0.86-1.58) | .33 | 0.78 (0.49-1.22) | .28 |

| Second remission (vs first remission) | 1.01 (0.69-1.49) | .95 | 1.09 (0.83-1.45) | .53 | 1.19 (0.90-1.59) | .23 | 1.21 (0.81-1.80) | .36 |

| Pre-HCT karyotype | ||||||||

| Normalized | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Not normalized | 1.13 (0.74-1.75) | .57 | 1.04 (0.75-1.43) | .58 | 1.15 (0.83-1.59) | .41 | 0.95 (0.58-1.55) | .84 |

| Non-MAC regimen (vs MAC) | 0.77 (0.51-1.18) | .24 | 1.19 (0.88-1.61) | .26 | 1.22 (0.89-1.67) | .22 | 1.94 (1.23-3.05) | .0041 |

| Not recovered pre-HCT blood counts∗ | 1.16 (0.85-1.59) | .35 | 1.13 (0.90-1.42) | .28 | 1.11 (0.87-1.40) | .41 | 1.08 (0.77-1.51) | .65 |

| HLA matching | ||||||||

| 10/10 HLA-identical related donor | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor | 0.79 (0.55-1.12) | .18 | 0.86 (0.66-1.11) | .24 | 0.85 (0.65-1.11) | .22 | 0.96 (0.66-1.41) | .84 |

| 1-2 allele/antigen-mismatched donor | 1.10 (0.67-1.81) | .70 | 1.42 (1.01-2.00) | .041 | 1.48 (1.04-2.11) | .029 | 1.72 (1.06-2.77) | .027 |

| HLA-haploidentical donor | 1.89 (0.88-4.05) | .10 | 1.82 (0.98-3.38) | .058 | 1.58 (0.82-3.04) | .17 | 1.65 (0.55-4.92) | .37 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 0.55 (0.29-1.04) | .065 | 0.77 (0.50-1.21) | .26 | 0.75 (0.47-1.18) | .21 | 1.08 (0.57-2.06) | .81 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||

| CNI + MMF w/wo sirolimus | 1.34 (0.84-2.14) | .22 | 1.31 (0.93-1.84) | 0.13 | 1.43 (1.01-2.04) | .046 | 1.17 (0.69-1.97) | .56 |

| CNI + MTX w/wo other | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| PTCy | 1.22 (0.73-2.04) | .45 | 0.90 (0.59-1.37) | .63 | 0.93 (0.60-1.44) | .75 | 0.57 (0.28-1.18) | .13 |

| CD3 chimerism at day +70 to +100 | ||||||||

| Mixed (<95%) | 1.08 (0.75-1.54) | .69 | 1.03 (0.80-1.32) | .81 | 1.03 (0.80-1.34) | .80 | 0.94 (0.66-1.35) | .75 |

| Full (≥95%) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Decreasing CD3 chimerism | ||||||||

| No (increase or <20% decrease) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Yes (≥20% decrease) | 0.48 (0.06-3.56) | .47 | 0.84 (0.26-2.71) | .77 | 0.98 (0.30-3.18) | .98 | 1.31 (0.30-5.67) | .72 |

| . | Risk of relapse . | Risk of relapse/death . | Risk of death . | Risk of NRM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 3.09 (2.19-4.38) | <.001 | 1.99 (1.51-2.62) | <.001 | 1.81 (1.36-2.40) | <.001 | 1.10 (0.68-1.78) | .71 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 7.66 (3.21-18.30) | <.001 | 5.80 (2.84-11.84) | <.001 | 5.57 (2.63-11.80) | <.001 | 4.70 (1.37-16.18) | .0014 |

| Age at HCT (per 10 y) | 0.97 (0.85-1.10) | .61 | 1.07 (0.97-1.18) | .18 | 1.09 (0.98-1.21) | .12 | 1.22 (1.04-1.44) | .013 |

| HCT-CI score | ||||||||

| 0-1 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 2-3 | 0.97 (0.70-1.36) | .88 | 1.17 (0.91-1.50) | .22 | 1.22 (0.94-1.58) | .14 | 1.45 (1.00-2.09) | .052 |

| ≥4 | 0.95 (0.65-1.38) | .78 | 1.21 (0.93-1.58) | .16 | 1.25 (0.95-1.66) | .11 | 1.59 (1.08-2.36) | .02 |

| Disease type | ||||||||

| De novo AML | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Secondary AML | 1.07 (0.74-1.55) | .72 | 1.06 (0.81-1.37) | .69 | 1.06 (0.80-1.40) | .68 | 1.05 (0.72-1.54) | .80 |

| MDS/AML | 0.66 (0.38-1.15) | .14 | 1.08 (0.75-1.55) | .68 | 1.21 (0.84-1.75) | .31 | 1.68 (1.03-2.72) | .036 |

| Cytogenetic risk | ||||||||

| Favorable | 0.67 (0.30-1.48) | .32 | 0.85 (0.52-1.40) | .52 | 0.83 (0.50-1.40) | .49 | 1.01 (0.53-1.91) | .98 |

| Intermediate | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Adverse | 1.71 (1.15-2.55) | .0085 | 1.22 (0.91-1.64) | .18 | 1.16 (0.86-1.58) | .33 | 0.78 (0.49-1.22) | .28 |

| Second remission (vs first remission) | 1.01 (0.69-1.49) | .95 | 1.09 (0.83-1.45) | .53 | 1.19 (0.90-1.59) | .23 | 1.21 (0.81-1.80) | .36 |

| Pre-HCT karyotype | ||||||||

| Normalized | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Not normalized | 1.13 (0.74-1.75) | .57 | 1.04 (0.75-1.43) | .58 | 1.15 (0.83-1.59) | .41 | 0.95 (0.58-1.55) | .84 |

| Non-MAC regimen (vs MAC) | 0.77 (0.51-1.18) | .24 | 1.19 (0.88-1.61) | .26 | 1.22 (0.89-1.67) | .22 | 1.94 (1.23-3.05) | .0041 |

| Not recovered pre-HCT blood counts∗ | 1.16 (0.85-1.59) | .35 | 1.13 (0.90-1.42) | .28 | 1.11 (0.87-1.40) | .41 | 1.08 (0.77-1.51) | .65 |

| HLA matching | ||||||||

| 10/10 HLA-identical related donor | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor | 0.79 (0.55-1.12) | .18 | 0.86 (0.66-1.11) | .24 | 0.85 (0.65-1.11) | .22 | 0.96 (0.66-1.41) | .84 |

| 1-2 allele/antigen-mismatched donor | 1.10 (0.67-1.81) | .70 | 1.42 (1.01-2.00) | .041 | 1.48 (1.04-2.11) | .029 | 1.72 (1.06-2.77) | .027 |

| HLA-haploidentical donor | 1.89 (0.88-4.05) | .10 | 1.82 (0.98-3.38) | .058 | 1.58 (0.82-3.04) | .17 | 1.65 (0.55-4.92) | .37 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 0.55 (0.29-1.04) | .065 | 0.77 (0.50-1.21) | .26 | 0.75 (0.47-1.18) | .21 | 1.08 (0.57-2.06) | .81 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||||||

| CNI + MMF w/wo sirolimus | 1.34 (0.84-2.14) | .22 | 1.31 (0.93-1.84) | 0.13 | 1.43 (1.01-2.04) | .046 | 1.17 (0.69-1.97) | .56 |

| CNI + MTX w/wo other | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| PTCy | 1.22 (0.73-2.04) | .45 | 0.90 (0.59-1.37) | .63 | 0.93 (0.60-1.44) | .75 | 0.57 (0.28-1.18) | .13 |

| CD3 chimerism at day +70 to +100 | ||||||||

| Mixed (<95%) | 1.08 (0.75-1.54) | .69 | 1.03 (0.80-1.32) | .81 | 1.03 (0.80-1.34) | .80 | 0.94 (0.66-1.35) | .75 |

| Full (≥95%) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Decreasing CD3 chimerism | ||||||||

| No (increase or <20% decrease) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Yes (≥20% decrease) | 0.48 (0.06-3.56) | .47 | 0.84 (0.26-2.71) | .77 | 0.98 (0.30-3.18) | .98 | 1.31 (0.30-5.67) | .72 |

Abbreviations are explained in Table 1.

Recovered: ANC ≥ 103/μL and platelets ≥ 105/μL; not recovered: ANC < 103/μL and/or platelets < 105/μL.

Pre- and/or post-HCT MRD as independent prognostic factor for post-HCT outcomes in distinct patient subsets

Among 935 patients, 69 received post-HCT maintenance therapy, including 57 patients receiving a tyrosine kinase inhibitor alone, 2 patients receiving a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in combination with a hypomethylating agent, 7 patients receiving a hypomethylating agent alone, 2 patients receiving a hypomethylating agent with a second agent (venetoclax or ruxolitinib), and 1 patient receiving a Janus kinase 2 inhibitor. We therefore performed a subset analysis in which we restricted the data set to 866 patients not receiving post-HCT maintenance therapy. As shown in Table 5, results were like those of the entire study cohort after multivariable adjustment.

Multivariable regression models for distinct patient subsets

| . | Risk of relapse . | Risk of relapse/death . | Risk of death . | Risk of NRM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML not receiving any post-HCT maintenance therapy (n = 866) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 2.99 (2.08-4.28) | <.001 | 1.93 (1.45-2.56) | <.001 | 1.79 (1.34-3.90) | <.001 | 1.08 (0.66-1.77) | .75 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 5.20 (1.82-14.90) | <.001 | 4.60 (2.05-10.31) | <.001 | 5.44 (2.41-12.28) | <.001 | 5.09 (1.45-17.85) | .011 |

| Patients with AML only (n = 851) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 3.34 (2.32-4.81) | <.001 | 2.15 (1.61-2.89) | <.001 | 2.04 (1.49-2.79) | <.001 | 1.11 (0.65-1.92) | .70 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 6.45 (2.51-16.58) | <.001 | 5.26 (2.47-11.18) | <.001 | 5.96 (3.22-11.18) | <.001 | 5.14 (1.47-17.94) | .010 |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML undergoing MAC (n = 569) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 3.81 (2.46-5.89) | <.001 | 2.31 (1.61-3.32) | <.001 | 2.09 (1.43-3.07) | <.001 | 1.16 (0.42-1.79) | .70 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 5.77 (1.63-20.38) | .005 | 6.39 (2.56-15.91) | <.001 | 6.50 (2.41-17.51) | <.001 | 9.41 (2.57-34.49) | <.001 |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML undergoing non-MAC (n = 366) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 2.16 (1.13-4.12) | .020 | 1.55 (0.98-2.46) | .062 | 1.32 (0.82-2.12) | .25 | 1.15 (0.60-2.23) | 0.38 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 7.44 (1.97-28.13) | .003 | 5.90 (1.74-20.06) | .004 | 7.14 (2.11-24.16) | .002 | Too few N to estimate- | - |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML receiving 10/10 HLA-identical/matched related or unrelated donor allograft (n = 685) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 2.56 (1.66-3.93) | <.001 | 1.78 (1.27-2.50) | <.001 | 1.57 (1.11-2.24) | .011 | 1.03 (0.58-1.83) | .91 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 8.08 (3.35-19.51) | <.001 | 5.33 (2.48-11.50) | <.001 | 5.01 (2.22-11.34) | <.001 | 2.71 (0.59-12.51) | .20 |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML with sufficient cytogenetic/molecular data for ELN 2022 risk classification (n = 521) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 2.75 (1.70-4.45) | <.001 | 2.01 (1.34-3.01) | .001 | 1.73 (1.12-2.67) | .013 | 0.98 (0.43-2.21) | .96 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 4.42 (1.28-15.20) | <.001 | 2.98 (1.02-8.66) | .045 | 3.44 (1.18-10.01) | .024 | 1.79 (0.21-14.87) | .59 |

| . | Risk of relapse . | Risk of relapse/death . | Risk of death . | Risk of NRM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML not receiving any post-HCT maintenance therapy (n = 866) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 2.99 (2.08-4.28) | <.001 | 1.93 (1.45-2.56) | <.001 | 1.79 (1.34-3.90) | <.001 | 1.08 (0.66-1.77) | .75 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 5.20 (1.82-14.90) | <.001 | 4.60 (2.05-10.31) | <.001 | 5.44 (2.41-12.28) | <.001 | 5.09 (1.45-17.85) | .011 |

| Patients with AML only (n = 851) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 3.34 (2.32-4.81) | <.001 | 2.15 (1.61-2.89) | <.001 | 2.04 (1.49-2.79) | <.001 | 1.11 (0.65-1.92) | .70 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 6.45 (2.51-16.58) | <.001 | 5.26 (2.47-11.18) | <.001 | 5.96 (3.22-11.18) | <.001 | 5.14 (1.47-17.94) | .010 |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML undergoing MAC (n = 569) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 3.81 (2.46-5.89) | <.001 | 2.31 (1.61-3.32) | <.001 | 2.09 (1.43-3.07) | <.001 | 1.16 (0.42-1.79) | .70 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 5.77 (1.63-20.38) | .005 | 6.39 (2.56-15.91) | <.001 | 6.50 (2.41-17.51) | <.001 | 9.41 (2.57-34.49) | <.001 |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML undergoing non-MAC (n = 366) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 2.16 (1.13-4.12) | .020 | 1.55 (0.98-2.46) | .062 | 1.32 (0.82-2.12) | .25 | 1.15 (0.60-2.23) | 0.38 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 7.44 (1.97-28.13) | .003 | 5.90 (1.74-20.06) | .004 | 7.14 (2.11-24.16) | .002 | Too few N to estimate- | - |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML receiving 10/10 HLA-identical/matched related or unrelated donor allograft (n = 685) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 2.56 (1.66-3.93) | <.001 | 1.78 (1.27-2.50) | <.001 | 1.57 (1.11-2.24) | .011 | 1.03 (0.58-1.83) | .91 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 8.08 (3.35-19.51) | <.001 | 5.33 (2.48-11.50) | <.001 | 5.01 (2.22-11.34) | <.001 | 2.71 (0.59-12.51) | .20 |

| Patients with AML and MDS/AML with sufficient cytogenetic/molecular data for ELN 2022 risk classification (n = 521) | ||||||||

| Pre-HCT/day +70 to +100 MRD dynamics | ||||||||

| MRDneg/MRDneg | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| MRDpos/MRDneg | 2.75 (1.70-4.45) | <.001 | 2.01 (1.34-3.01) | .001 | 1.73 (1.12-2.67) | .013 | 0.98 (0.43-2.21) | .96 |

| MRDpos/MRDpos | 4.42 (1.28-15.20) | <.001 | 2.98 (1.02-8.66) | .045 | 3.44 (1.18-10.01) | .024 | 1.79 (0.21-14.87) | .59 |

Because our study cohort was heterogeneous regarding patient and donor characteristics, we examined the interplay between MFC MRD data and post-HCT outcomes in additional subset analyses in which we restricted our data set to 851 patients with AML, 569 patients with AML or MDS/AML who underwent HCT after receiving MAC therapy, 366 patients with AML or MDS/AML who underwent HCT after receiving non-MAC therapy, 685 patients with AML or MDS/AML who received an allograft from a 10/10 HLA-identical/matched related or unrelated donor, or 521 patients with sufficient cytogenetic/molecular data to classify their risk based on ELN 2022 criteria. Acknowledging limitations of small sample sizes, findings in these subsets were generally like those obtained in the entire study cohort regarding relationship between per-HCT MRD dynamics and post-HCT outcomes after multivariable adjustment.

Discussion

Because of the association between detectable residual leukemia cells and increased risk of relapse and shorter survival, MRD testing is nowadays widely used before allografting for prognostication and, increasingly, to guide treatment decision-making in patients with AML in morphologic remission presenting for consideration of allogeneic HCT. Confirming our earlier reports,6,8-14,18,19,22-27 and in line with data from other investigators,2-5 our analyses presented herein show that a positive pre-HCT MRD test identifies a subset of patients with substantially increased risk of relapse and inferior survival relative to patients without MRD. Consistent with prior knowledge, they also demonstrate that many of the relapses occur early after allografting. Specifically, in our cohort, over half of the patients (263/425 [62%]) relapsing after HCT did so within the first 100 days after stem cell infusion. Unsurprisingly, such early relapses were more common among patients with pre-HCT MRD relative to those without, highlighting the value of pre-HCT MRD as a marker for poor short-term outcomes in patients with AML who received HCT in morphologic remission.

In this study, we focused on adults with AML or MDS/AML who survived 100 days after allografting without experiencing disease recurrence. Because it is standard practice at our institution to obtain bone marrow restaging studies that include MFC MRD assessments at ∼3 months after HCT, we were able to examine the role of MRD testing in these patients; in what way, if any, such testing helps in identifying later relapses has, to this point, been unclear.

As a first main finding, our study indicates that pre-HCT MRD is strongly and independently associated with increased relapse and shorter survival in patients who underwent allografting and survived 100 days without experiencing disease recurrence. In fact, with 3-year relapse estimates of 40% vs 15% and 3-year survival estimates of 48% vs 76% among patients with pre-HCT MRD and those without, the presence of MRD before allogeneic HCT proved a predominant indicator of poor outcome in our cohort.

As a second main finding, having MFC evidence of MRD 70 to 100 days after allogeneic HCT is uncommon among individuals who did not experience a leukemia relapse within the first 100 days. In our cohort, MRD was present in only 1% of the patients. Not surprisingly, these patients had substantially inferior outcomes compared to the patients testing MRDneg at that time point. The higher proportion of patients with MRD before HCT than 70 to 100 days after HCT (15% vs 1% in our cohort of individuals who did not experience a leukemia relapse within the first 100 days) indicates that many patients with pre-HCT MRD will convert to MRD negativity over the first 100 days after allografting. Indeed, this was the case in 92% of MAC patients with pre-HCT MRD and 93% of non-MAC patients with pre-HCT MRD.

As a third main finding, our analyses indicate that MRD data obtained on day +70 to +100 after HCT are most informative when considered together with pre-HCT MRD data, that is, in the context of MRD dynamics. Assessment of MRD dynamics showed outcomes of MRD “converters” (ie, patients who are MRDpos/MRDneg) were superior to those who remained MRDpos (ie, patients who are MRDpos/MRDpos) but were significantly inferior to those testing MRDneg at both time points (ie, patients who are MRDneg/MRDneg). Thus, MRD conversion confers only partial improvement in outcomes, arguing against interpretation of day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD data in isolation. These findings, highlighting not only the central importance of pre-HCT MRD but also the consideration of peri-HCT MRD dynamics, are reminiscent of those obtained in a recent study in which we assessed the dynamics of MRD assessed before and around day +28 after allografting.6 That said, although day +70 to +100 post-HCT MRD data can refine prognostication of adults with AML or MDS/AML who do not experience a relapse of their myeloid neoplasm within the first 100 days after allografting, there may be limited value of MRD testing for treatment decision-making at this time point given the rare occurrence of a positive result (and current lack of robust data indicating improved outcomes when relapses are treated early at the MRD level) and the fact that patients at high risk of relapse can be identified via pre-HCT MRD.

Because of routine MFC MRD testing with an assay that has been introduced in early 2006 and has shown stable performance characteristics over time,6,12 we were able to study a large number of patients. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this is a retrospective study with its inherent selection biases, with largely nonrandomized assignment of patients to different conditioning intensities. Second, methodologies for MFC-based MRD testing vary widely between individual institutions/laboratories, and results from our assay may not be directly translatable to other testing platforms. Likewise, polymerase chain reaction–based or next-generation sequencing–based molecular MRD testing, which may provide complementary prognostic information to MFC MRD testing,28 was not routinely done in our study cohort and may yield, alone or in conjunction with MFC MRD testing, results that could differ from those reported herein. Third, mutational data were unavailable for many patients, thus limiting risk stratification to cytogenetic information only. And fourth, no uniform approach was taken when leukemia cells were detected at the submicroscopic or microscopic level, with various therapies (including expedited withdrawal of immunosuppressive agents, donor lymphocyte infusions, hypomethylating or molecularly targeted agents, and intensive chemotherapy) being used simultaneously or sequentially. Acknowledging these limitations, our study identifies the prognostic significance of MFC MRD testing at ∼3 months after HCT in a large cohort of patients with AML and MDS/AML. Among patients without relapse or death before this time mark, MRD positivity is not common. However, when present, it denotes a substantially increased risk of relapse and poor survival relative to patients testing negative for MFC MRD at that time. Most importantly, although a significant proportion of patients with pre-HCT MRD positivity have cleared MRD by 3 months, their outcomes are only minimally improved to those who have not and are substantially worse compared with patients testing negative for MRD before HCT. Thus, pre-HCT MRD remains a predominant risk factor for relapse and poor outcome even in patients who have remained leukemia-free for the first 100 days after allografting. Our data suggest all such patients should be considered for MRD-directed therapies to reduce relapse risks and improve post-HCT survival. For individuals with FLT3 internal tandem duplication–mutated AML, increasing evidence indicates value of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for this purpose.29-31 Other targeted therapeutics of interest include inhibitors or mutated IDH and menin inhibitors, which are generally well tolerated and have anti-AML efficacy32-35 although their potential merits as MRD-directed treatments after allogeneic HCT remain to be determined, ideally in the setting of well-designed clinical trials. Likewise, for all other subsets of patients with pre-HCT MRD, participation in controlled trials should be encouraged to evaluate preemptive/maintenance treatment strategies after allografting. Finally, considering many patients with pre-HCT MRD cleared MRD by 3 months yet have outcomes that are only minimally better than those with persistent MRD, our findings also highlight the need for further careful examination whether or in what way peri-HCT “MRD conversion” could serve as surrogate end point in a clinical trial.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grants P01-CA078902, P01-CA018029, and P30-CA015704 from the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health. R.B.W. acknowledges support from the José Carreras/E. Donnall Thomas Endowed Chair for Cancer Research.

Authorship

Contribution: N.A. and R.B.W. conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to the collection and assembly of data, and participated in data analysis and interpretation and drafting of the manuscript; M.O. conducted all statistical analyses and participated in data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript; E.R.-A., C.O., C.D., and R.S.B. contributed to the collection and assembly of data; F.M., B.M.S., and F.R.A. contributed to the provision of study material, patient recruitment, and acquisition of data; and all authors revised the manuscript critically and gave final approval to submit for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Roland B. Walter, Translational Science and Therapeutics Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, 1100 Fairview Ave N, D1-100, Seattle, WA 98109-1024; email: rwalter@fredhutch.org.

References

Author notes

For original, deidentified data, please contact the corresponding author, Roland B. Walter (rwalter@fredhutch.org).