Key Points

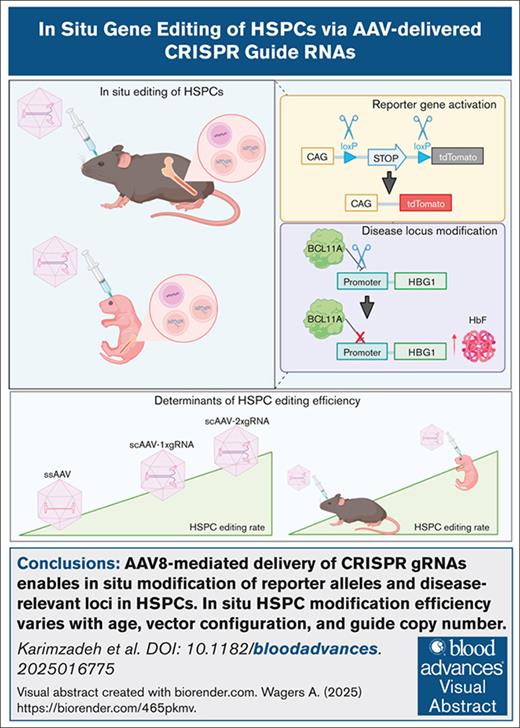

AAV serotype 8–mediated delivery of CRISPR gRNAs enables in situ modification of reporter alleles and disease-relevant loci in HSCs.

In situ HSC modification efficiency varies with age, vector configuration, and guide copy number.

Visual Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are self-renewing, multipotent, and engraftable precursors of all blood cells. Efficient delivery of therapeutic gene products and gene editing machinery to correct disease-causing gene variants in endogenous HSCs while they remain in the body holds exciting potential to leverage HSC potency for the treatment of monogenic blood disorders. Toward this goal, we used adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver CRISPR guide RNAs (gRNAs) to edit HSC genomes in situ in Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP transgenic mice carrying a Cas9-activatable Lox-STOP-Lox-tdTomato reporter cassette together with a constitutive SpCas9-2A-EGFP. Using a variety of conditions and vector designs, we tested whether systemic administration to these mice of AAVs carrying SpCas9-compatible gRNAs designed to cut DNA upstream and downstream of the STOP cassette would induce tdTomato expression in HSCs. Our findings identify self-complementary AAVs (scAAVs) and increased ratio of guide to Cas9 as parameters facilitating higher editing efficiency. Of note, we find preserved multilineage output and engraftability of HSCs upon scAAV-gRNA editing. In an example application of this technology, we explore the potential for in situ HSC gene editing by dual AAV-CRISPR delivery and demonstrate robust gene modification, concurrent with induction of therapeutic fetal hemoglobin, in a sickle cell disease mouse model modified to express SpCas9. In summary, this work offers a sensitive and adaptable platform that allows robust modification of HSC genomes in situ.

Introduction

Self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) can efficiently reconstitute all adult blood cell compartments upon transplantation, making HSC transplantation a curative intervention for monogenic blood disorders.1 Ex vivo methods for HSC gene modification, such as Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD), successfully use HSC’s DNA repair machinery to rescue genetic abnormalities.2-6 However, the ex vivo isolation and manipulation of HSCs can diminish their subsequent engraftment efficiency and multilineage potency and may introduce unwanted selective pressures with potential long-term negative consequences.7 HSC transplantation itself also requires complicated procedures and extensive infrastructure, posing a challenge to global access.8-10 Approaches that target HSCs while they remain in the body hold promise to overcome these difficulties.

Among currently available in vivo gene therapy vectors, recombinant adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) exhibit desirable safety profiles and effectiveness. To date, AAVs have been use in hundreds of clinical trials for gene replacement and, more recently, gene editing approaches,11-13 with US Food and Drug Administration approvals issued for several inherited disorders.14-16 However, thus far, in situ–delivered AAV-based gene therapeutics have yet to be tested or approved for use in targeting HSCs for the treatment of genetic blood cell diseases.

We, and others, previously reported successful in situ transduction and genetic modification of HSCs in mice by systemic administration of AAV-Cre to Ai9 transgenic animals, which harbor a single Cre-targetable LoxP-STOP-LoxP cassette upstream of tdTomato.17,18 Our laboratory demonstrated Cre-mediated excision and consequent induction of tdTomato fluorescence in ∼20% (on average) of bone marrow (BM) HSCs in AAV-Cre injected mice, with the most robust tdTomato induction observed with AAV serotype 8 (AAV8). Importantly, AAV-Cre–transduced HSCs retained normal engraftment and reconstitution capacity when subsequently transplanted into irradiated hosts, demonstrating preservation of full stem cell potency after this in situ gene modification approach.19 Here, we adapt the AAV delivery platform for CRISPR-based gene editing and define specific design and delivery criteria needed for optimal in situ HSC modification.

To our knowledge, this study represents the first report of AAV-mediated delivery of CRISPR guide RNAs (gRNAs) for in situ genome modification of HSCs and the first systematic evaluation of the specific features of vector design and delivery that affect editing outcome and efficacy. Furthermore, applying this approach in a mouse model of SCD, we demonstrate robust therapeutic gene modification of HSCs in situ, accompanied by induction of fetal hemoglobin in red blood cells (RBCs). These data provide a compelling example of the exciting potential of this AAV delivery system to accomplish targeted manipulation of hematologically relevant genes without the need for HSC isolation and transplantation.

Methods

Mice

Mice were housed at the Joslin Diabetes Center, and all procedures were approved by the Joslin Diabetes Center institutional animal care and use committee. Mice used included: Rosa26-Cas9 knockin (B6J.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1.1(CAG-cas9∗,-EGFP)Fezh/J; strain number 026179; C57BL/6J background), Ai9 (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J; strain number 007909; C57BL/6J background), NSG (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ; strain number 005557), and Townes (B6;129-Hbbtm2(HBG1,HBB∗)Tow/Hbbtm3(HBG1,HBB)TowHbatm1(HBA)Tow/J; strain number 013071). See the supplemental Methods regarding the generation of Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP and Townes;SpCas9-EGFP mice.

AAV vectors and administration

All AAVs are serotype 8. ssAAV-1xgRNAs, scAAV-1xgRNAs, and scAAV-2xgRNAs vectors were produced by the Penn Vector Core (Gene Therapy Program, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) or the MEEI Gene Transfer Vector Core at the Schepens Eye Research Institute. scAAV-3xHBG1.gRNA was generated as described in the supplemental Methods. For systemic administration of AAV and vehicle, 5- to 8-week-old male and female animals were injected retro-orbitally, and postnatal day 1 (P1) to P3 neonates were injected via the facial vein. Injection and mobilization protocols are available in supplemental Methods.

Flow cytometry

Processing of BM, spleen, peripheral blood, and thymus to obtain single-cell suspensions for flow cytometry are detailed in the supplemental Methods. Staining was performed in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline, 2 mM EDTA, and 2% fetal bovine serum) after filtering through 40-micron strainer. In most cases, RBCs were lysed using ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer (catalog no. A1049201; Gibco), except for erythrocyte analysis, for which BM cells were processed without ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis. All stains are detailed in the supplemental Methods. Flow cytometric data were acquired using BD LSRFortessa and BD FACSAria II instruments. Data analysis was performed with FlowJo (BD Biosciences).

FACS

All sorts were performed on BD FACSAria II instrument using 4-way purity setting except when sorting HSCs for DNA extraction and next-generation sequencing processing, for which cells were sorted using a 96-well plate format.

Transplantation

Lineage low (Linlo) c-kit positive (Kit+) progenitors were sorted from tdTomato− or tdTomato+ BM cell fractions for transplantation into 9- to 12-week-old NSG recipients, previously irradiated with 150 rads using a MultiRad225 X-ray irradiator (Precision X-ray). Donor cells were administered by retroorbital injection in 75 μL of FACS buffer using 31-gauge insulin syringes. Recipients were kept on antibiotic water containing 0.6 mg/mL sulfadiazine/trimethoprim for 4 weeks after transplantation. Mice were bled via tail-vein incision at 4-week intervals and up to 12 weeks after transplant. See supplemental Methods for details of chimerism analysis and criteria for successful engraftment.

Colony-forming unit (CFU) assay

HSCs were sorted onto MethoCult media in SmartDish 6-well plates and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (STEMCELL Technologies); 12 days later, colonies were scored by light microscopy after blinding of experimental identity.

DNA extraction and next-generation sequencing

DNA was extracted from sorted cells using DNA QuickExtract solution as described.20 Extracted DNA was used as template for polymerase chain reaction to amplify the CRISPR target site in the HBG1 promoter. See supplemental Information for primer sequences and additional details. Amplicon sequencing was performed at the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Computational and Integrative Biology DNA Core. Sequencing reads were analyzed using CRISPResso2.21

Statistical analysis and illustrations

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Illustrations were generated using BioRender.com.

Reagents

A complete list of reagents is included in the supplemental Information.

The supplemental Methods, including details of aforementioned procedures as well as fetal hemoglobin (HbF) induction, cloning, liver vector copy number, muscle editing, complete blood counts, and toxicity analyses can be found in the supplemental Information.

Results

Mouse model and vector design for in situ CRISPR editing

To establish a sensitive and robust system in which to assess the efficiency and impact of in situ editing of genes in HSCs by CRISPR-Cas9, we crossed Streptococcus pyogenes (Sp) Cas9-expressing transgenic mice to Ai9 animals, hereafter “Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP.” Transgenic SpCas9-EGFP mice exhibit constitutive and widespread expression of SpCas9 and EGFP driven from the Rosa26 locus under the control of a CAG promoter.22 Ai9 mice carry a CMV-Lox-STOP-Lox-tdTomato transgene, also knocked into Rosa26.23 Importantly, previous work from our group demonstrated in muscle tissue that this canonical Cre-reporter allele can be repurposed to serve as a CRISPR/Cas9 reporter by dual gRNA targeting of sequences flanking the Ai9 Lox-STOP-Lox cassette, which excises the intervening DNA and induces subsequent expression of tdTomato24 (Figure 1A). By nucleofection of fibroblasts isolated from Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice, we identified a 5′ and 3′ gRNA pair for use with SpCas9 (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Table 1). Next, we produced AAVs encoding the selected gRNA combination in 3 different formats: (1) single-stranded AAV (ssAAV); (2) self-complementary AAV (scAAV) carrying 1 copy of each gRNA, driven by U6 promoters (named ssAAV-1xgRNAs and scAAV-1xgRNAs, respectively); and (3) scAAV-2xgRNAs that incorporated 1 additional copy of each guide (Figure 1B).

Impact of vector design on CRISPR-mediated gene editing of HSCs and more mature hematopoietic lineages in situ in adult Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice. (A) Schematic of Ai9 transgene in Rosa26 locus. Double-stranded break induction and excision of LoxP-flanked STOP cassette can be detected by robust tdTomato expression. Triangles: LoxP sites. (B) Vector design. ssAAV or scAAVs carrying gRNAs driven by U6, H1, or 7SK promoters. ssAAV-1xgRNAs and scAAV-1xgRNAs carry 1 copy of each gRNA, whereas scAAV-2xgRNAs encode 2 copies of each gRNA. (C-E) Frequency of tdTomato+ cells among BM HSCs in adult (5 to 8-week-old) animals receiving IV injections of vehicle or AAV and analyzed 5 weeks after injection. Animals received vehicle only or 5 × 1011 vg or 5 × 1012 vg per animal of ssAAV-1xgRNAs (C), vehicle only or 5 × 1012 vg of either ssAAV-1xgRNAs or scAAV-1xgRNAs (D), or vehicle only or 5 × 1012 vg per animal of either scAAV-1xgRNAs or scAAV-2xgRNAs (E). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001. Data compiled from 2 (panels C-D) or 4 (panel E) independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. (F) Frequency of tdTomato+ cells among different cellular subsets in the spleen, BM, or thymus of Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice injected with vehicle or 5 × 1012 vg per mouse scAAV-2xgRNAs. B cell, B220+; T cell, CD3+; myeloid, B220−CD3−, EryA, CD71highTer119+; EryB, CD71intermediateTer119+, EryC, CD71−Ter119+; CD4 SP, CD3+CD4+CD8−; DP, CD3+CD4+CD8+; DN, CD3+CD4−CD8−; CD8 SP, CD3+CD4−CD8+. Unpaired t test with Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 3 independent experiments. dITR, defective inverted terminal repeat; DN, double negative; DP, double positive; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; EryA, basophilic erythroblasts; SP, single positive. Panels A and B created with biorender.com. Karimzadehfard A. (2025) https://biorender.com/1fldmz.

Impact of vector design on CRISPR-mediated gene editing of HSCs and more mature hematopoietic lineages in situ in adult Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice. (A) Schematic of Ai9 transgene in Rosa26 locus. Double-stranded break induction and excision of LoxP-flanked STOP cassette can be detected by robust tdTomato expression. Triangles: LoxP sites. (B) Vector design. ssAAV or scAAVs carrying gRNAs driven by U6, H1, or 7SK promoters. ssAAV-1xgRNAs and scAAV-1xgRNAs carry 1 copy of each gRNA, whereas scAAV-2xgRNAs encode 2 copies of each gRNA. (C-E) Frequency of tdTomato+ cells among BM HSCs in adult (5 to 8-week-old) animals receiving IV injections of vehicle or AAV and analyzed 5 weeks after injection. Animals received vehicle only or 5 × 1011 vg or 5 × 1012 vg per animal of ssAAV-1xgRNAs (C), vehicle only or 5 × 1012 vg of either ssAAV-1xgRNAs or scAAV-1xgRNAs (D), or vehicle only or 5 × 1012 vg per animal of either scAAV-1xgRNAs or scAAV-2xgRNAs (E). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001. Data compiled from 2 (panels C-D) or 4 (panel E) independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. (F) Frequency of tdTomato+ cells among different cellular subsets in the spleen, BM, or thymus of Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice injected with vehicle or 5 × 1012 vg per mouse scAAV-2xgRNAs. B cell, B220+; T cell, CD3+; myeloid, B220−CD3−, EryA, CD71highTer119+; EryB, CD71intermediateTer119+, EryC, CD71−Ter119+; CD4 SP, CD3+CD4+CD8−; DP, CD3+CD4+CD8+; DN, CD3+CD4−CD8−; CD8 SP, CD3+CD4−CD8+. Unpaired t test with Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 3 independent experiments. dITR, defective inverted terminal repeat; DN, double negative; DP, double positive; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; EryA, basophilic erythroblasts; SP, single positive. Panels A and B created with biorender.com. Karimzadehfard A. (2025) https://biorender.com/1fldmz.

In situ HSC editing via AAV-delivered CRISPR gRNAs in adult injected animals

To test the ability of AAV-delivered gRNAs to mediate CRISPR-targeted genome modification in HSCs and other hematopoietic cells in situ, we injected 5- to 8-week-old Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice IV with different doses and formats of AAV-gRNA vectors, and analyzed gene editing efficiencies 5 weeks later by flow cytometry for tdTomato (supplemental Figure 2). Delivery of ssAAV-1xgRNAs at 5 × 1012 vector genomes (vg) per animal (equivalent to ∼2.4 × 1014 vg/kg) yielded rare, but readily detectable, gene-edited HSCs, with an average of 0.6% ± 0.3% tdTomato+ HSCs in the BM (Figure 1C). Delivery using scAAV vectors yielded an approximate sixfold increase in the percentage of tdTomato+ HSCs, reaching an average 3.7% ± 1.2% tdTomato+ HSCs (Figure 1D). Altering the gRNA:Cas9 ratio, by inclusion of additional gRNA copies in the AAV, further increased in situ HSC editing rates, with scAAV-2xgRNA vectors, bearing 2 copies of each gRNA, producing an average of 5.8% ± 1.2% tdTomato+ BM HSCs (Figure 1D). We also used a rapid HSC mobilization protocol25 to explore whether acute increases in HSC abundance in the periphery at the time of AAV administration might boost in vivo gene editing rates but found comparable frequencies of tdTomato+ HSCs in mobilized and unmobilized mice (supplemental Figure 3).

We additionally quantified tdTomato expression across more mature blood cell types in the spleen, BM, and thymus of animals injected with vehicle alone or with 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV-2xgRNAs. Gene editing was detectable in almost all cell populations analyzed, although generally at lower frequencies than levels detected in HSCs (Figure 1E). Consistent with the progressive enucleation of BM orthochromatic erythroblast and reticulocytes, tdTomato expression decreased to barely detectable levels in this population in AAV-gRNA–treated animals, reminiscent of our previous findings with AAV-Cre in the Ai9 reporter model.19,26 Importantly, we observed no differences in body weight, tracked over time, or in liver histopathology or serum inflammatory markers, assessed at the experimental end point, among control and AAV-treated animals (supplemental Figure 4). Altogether, these results identify multiple vector design features that can be leveraged to enhance in situ HSC editing via AAV delivery in the absence of detectable toxicity.

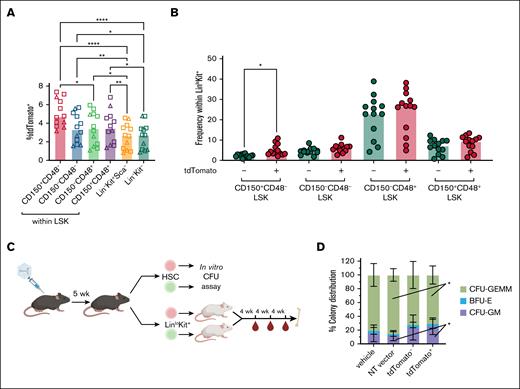

Functionality of in situ gene-edited HSCs

Next, we investigated possible functional consequences of in situ gene targeting for HSC biology. In animals receiving scAAV-2xgRNAs, the frequency of tdTomato positivity was uniquely higher in HSCs than in more differentiated progenitor populations (Figure 2A). We used EGFP as a surrogate to investigate levels of SpCas9 expression in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and found that EGFP signal intensity is higher in HSCs than in non-HSC LinloSca-1+c-kit+ (LSK) progenitors and LinloKit− populations but comparable with LinloKit+Sca− myeloid cell precursors (supplemental Figure 5). We also investigated differences in the frequencies of primitive progenitors within the tdTomato− vs tdTomato+ subsets of LinloKit+ BM cells and found that HSCs appeared overrepresented in the tdTomato+ fraction (5.1 ± 2.8), compared with the tdTomato− subset (2.4 ± 0.8); whereas more differentiated progenitor cells appeared equally distributed between the tdTomato− and tdTomato+ fractions (Figure 2B).

Functional analyses of in situ gene-edited HSCs. (A) Frequency of tdTomato+ cells among HSCs (CD150+CD48−LSK) or among the indicated subsets of BM progenitors in adult injected animals 5 weeks after receiving 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV-2xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. (B) Frequency of primitive progenitors within tdTomato− and tdTomato+ subsets of LinloKit+ BM progenitors at 5 weeks after injection of adult animals with 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV-2xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. (C) Experimental design. For CFU assay, HSCs from animals injected with vehicle or NT vector (all tdTomato−), and tdTomato+ or tdTomato− HSCs from animals receiving 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV carrying targeting gRNAs, were sorted 5 weeks after injection and plated in methylcellulose. Colonies were scored visually at day 12. For transplant, LinloKit+ HSPCs from the tdTomato+ or tdTomato− fractions of the BM were sorted and transplanted into sublethally irradiated NSG recipients. Peripheral blood was analyzed by FACS every 4 weeks, and mice were euthanized >1 week after last bleed for BM chimerism analysis (Table 1; supplemental Figure 6 for results). (D) Percentages of CFU-GEMM, BFU, and CFU-GM formed from HSCs sorted from animals injected with vehicle or NT vector, or from tdTomato+ or tdTomato− HSCs sorted from animals injected as adults with 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV carrying targeting gRNAs. Total number of colonies scored is as follows: vehicle, 288; NT vector, 264; tdTomato−, 279; and tdTomato+, 225. Individual colony numbers provided in supplemental Table 2. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05. Data compiled from 2 independent experiments. BFU-E, burst-forming unit-erythroid; CFU, colony-forming unit; GEMM, granulocyte, erythrocyte, macrophage, megakaryocyte; GM, granulocyte, macrophage; NT, nontargeting. Panel C created with biorender.com. Karimzadehfard A. (2025) https://biorender.com/mz1lx3u.

Functional analyses of in situ gene-edited HSCs. (A) Frequency of tdTomato+ cells among HSCs (CD150+CD48−LSK) or among the indicated subsets of BM progenitors in adult injected animals 5 weeks after receiving 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV-2xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. (B) Frequency of primitive progenitors within tdTomato− and tdTomato+ subsets of LinloKit+ BM progenitors at 5 weeks after injection of adult animals with 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV-2xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. (C) Experimental design. For CFU assay, HSCs from animals injected with vehicle or NT vector (all tdTomato−), and tdTomato+ or tdTomato− HSCs from animals receiving 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV carrying targeting gRNAs, were sorted 5 weeks after injection and plated in methylcellulose. Colonies were scored visually at day 12. For transplant, LinloKit+ HSPCs from the tdTomato+ or tdTomato− fractions of the BM were sorted and transplanted into sublethally irradiated NSG recipients. Peripheral blood was analyzed by FACS every 4 weeks, and mice were euthanized >1 week after last bleed for BM chimerism analysis (Table 1; supplemental Figure 6 for results). (D) Percentages of CFU-GEMM, BFU, and CFU-GM formed from HSCs sorted from animals injected with vehicle or NT vector, or from tdTomato+ or tdTomato− HSCs sorted from animals injected as adults with 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV carrying targeting gRNAs. Total number of colonies scored is as follows: vehicle, 288; NT vector, 264; tdTomato−, 279; and tdTomato+, 225. Individual colony numbers provided in supplemental Table 2. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05. Data compiled from 2 independent experiments. BFU-E, burst-forming unit-erythroid; CFU, colony-forming unit; GEMM, granulocyte, erythrocyte, macrophage, megakaryocyte; GM, granulocyte, macrophage; NT, nontargeting. Panel C created with biorender.com. Karimzadehfard A. (2025) https://biorender.com/mz1lx3u.

To assess potential functional differences between the edited (tdTomato+) and unedited (tdTomato−) progenitor subsets in AAV-injected Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice, we performed CFU and transplantation assays (Figure 2C). CFU assays revealed comparable distribution of colony types when comparing tdTomato− with tdTomato+ HSCs sorted from scAAV-2xgRNAs group or when comparing AAV-CRISPR–injected groups with vehicle-injected controls (Figure 2D; supplemental Table 2). These data suggest that the in vitro myeloid differentiation potential of HSCs edited in situ is not altered by the introduction of CRISPR-mediated genomic modifications via AAV delivery.

Next, to assess long-term engraftment and hematopoietic reconstitution abilities, we transplanted tdTomato+ or tdTomato− LinloKit+ progenitors sorted from Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP donors previously injected with scAAV-1xgRNAs/scAAV-2xgRNAs (Figure 2C) into conditioned recipient mice. Donor tdTomato+ or tdTomato− cells were transferred at low or high doses, as detailed in Table 1. A “high donor number” group of recipients (Table 1) was included to account for differences in phenotypic HSC frequency observed within the LinloKit+ subsets of tdTomato− vs tdTomato+ BM (Figure 2B). EGFP was used to mark donor-derived cells for subsequent blood and BM analyses (supplemental Figure 6A-B). Twelve weeks after transplantation, we found higher levels of donor-derived total blood cells in animals transplanted with low numbers of tdTomato+ cells (55.0%; standard deviation [SD], 28.0%) in comparison with those receiving equivalent numbers of tdTomato− cells (10.5%; SD, 6.3%). Interestingly, donor cell chimerism in recipients of low numbers of tdTomato+ cells was comparable with chimerism in recipients receiving “high donor number” tdTomato− cells (58.5%; SD, 26.6%; Table 1; supplemental Figure 6C), reflecting the aforementioned differences in phenotypic HSC content within the tdTomato+ and tdTomato− cell subsets.

In vivo engraftment of in situ gene-edited HSPCs

| Donor . | Donor cell no. (×1000) . | Donor-derived chimerism in the blood (12 week), % . | No. of successful granulocyte donor chimerism/total . | Donor-derived HSPC chimerism (BM), % . | No. of successful HSPC donor chimerism/total . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total . | B cell . | T cell . | Macrophage . | Granulocyte . | |||||

| tdTomato+ | 10 | 48.3 | 92 | 68 | 32.9 | 16.4 | 5/6 | 78.6 | 5/6 |

| 7.8 | 92.9 | 99.5 | 99.9 | 96.6 | 90.7 | 94.5 | |||

| 11 | 52 | 93.7 | 95.5 | 32.7 | 19.9 | 20.4 | |||

| 5 | 16.2 | 97.7 | 89.4 | 1.38 | 0.22 | 0.064 | |||

| 5 | 39.6 | 93.8 | 74.1 | 12.5 | 2.96 | 27.1 | |||

| 5 | 81.2 | 98.8 | 91.7 | 12.6 | 1.88 | 6.76 | |||

| tdTomato− | 10 | 10.8 | 79.6 | 74.5 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 1/5 | 0.14 | 0/4 |

| 8.9 | 9.05 | 91.2 | 95.7 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.23 | |||

| 5 | 4.11 | 8.74 | 71.5 | 0.14 | 0.034 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 20.9 | 96.6 | 61.5 | 0.64 | 0.19 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 7.72 | 91.2 | 88.9 | 0.15 | 0.29 | nd | |||

| “High donor number” tdTomato− | 30 | 74.9 | 98.5 | 95 | 14.9 | 4.63 | 4/4 | 29.2 | 3/4 |

| 17.7 | 77.4 | 99.5 | 99.2 | 41.6 | 18.2 | 45.4 | |||

| 15 | 61.8 | 99.4 | 95.7 | 7.04 | 7.62 | 13.4 | |||

| 15 | 19.9 | 91.3 | 92.2 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0 | |||

| Donor . | Donor cell no. (×1000) . | Donor-derived chimerism in the blood (12 week), % . | No. of successful granulocyte donor chimerism/total . | Donor-derived HSPC chimerism (BM), % . | No. of successful HSPC donor chimerism/total . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total . | B cell . | T cell . | Macrophage . | Granulocyte . | |||||

| tdTomato+ | 10 | 48.3 | 92 | 68 | 32.9 | 16.4 | 5/6 | 78.6 | 5/6 |

| 7.8 | 92.9 | 99.5 | 99.9 | 96.6 | 90.7 | 94.5 | |||

| 11 | 52 | 93.7 | 95.5 | 32.7 | 19.9 | 20.4 | |||

| 5 | 16.2 | 97.7 | 89.4 | 1.38 | 0.22 | 0.064 | |||

| 5 | 39.6 | 93.8 | 74.1 | 12.5 | 2.96 | 27.1 | |||

| 5 | 81.2 | 98.8 | 91.7 | 12.6 | 1.88 | 6.76 | |||

| tdTomato− | 10 | 10.8 | 79.6 | 74.5 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 1/5 | 0.14 | 0/4 |

| 8.9 | 9.05 | 91.2 | 95.7 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.23 | |||

| 5 | 4.11 | 8.74 | 71.5 | 0.14 | 0.034 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 20.9 | 96.6 | 61.5 | 0.64 | 0.19 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 7.72 | 91.2 | 88.9 | 0.15 | 0.29 | nd | |||

| “High donor number” tdTomato− | 30 | 74.9 | 98.5 | 95 | 14.9 | 4.63 | 4/4 | 29.2 | 3/4 |

| 17.7 | 77.4 | 99.5 | 99.2 | 41.6 | 18.2 | 45.4 | |||

| 15 | 61.8 | 99.4 | 95.7 | 7.04 | 7.62 | 13.4 | |||

| 15 | 19.9 | 91.3 | 92.2 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0 | |||

Donor-derived chimerism in the peripheral blood and BM of NSG recipients that received transplantation with the indicated number of tdTomato+ or tdTomato− LinloKit+ HSPCs from Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP animals previously injected with 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV encoding targeting gRNAs. Donors are grouped into equal donor cell number (at ∼7000 donor cells) tdTomato+ or tdTomato− source; the “high donor number” condition, averaging 20 000 donor cells (for tdTomato− donor source only), was included to provide functional assessment of the higher frequency of phenotypic HSCs in tdTomato+ LinloKit+, compared with tdTomato− counterparts (Figure 2B). Blood chimerism 12 weeks after transplant is shown for the following populations: total (CD45+), B cell (B220+), T cell (CD3+), macrophage (CD3−B220−CD11b+), granulocyte (CD3−B220−CD11b+Gr1+). Percent donor-derived HSPCs (LinloKit+CD150+CD48−) is also shown for individual animals. “Successful engraftment” is determined as outlined in supplemental Methods and displayed in bold font.

nd, not determined.

Next, we assessed blood granulocyte chimerism as a peripheral indicator of BM HSC chimerism.27 In recipients receiving equivalent numbers of donor cells, 1 of 5 recipients of tdTomato− cells showed persistent blood granulocyte chimerism, whereas 5 of 6 recipients of tdTomato+ cells exhibited persistent donor-derived granulocyte chimerism (supplemental Figure 6D; Table 1). Of 4 recipients of “high donor number” tdTomato− cells, 3 showed blood granulocyte chimerism, presumably due to the increased abundance of HSCs among the transplanted donor cells, which is similar to the HSC number present in the lower dose of tdTomato+ LinloKit+ progenitors (Table 1; supplemental Figure 6D).

Finally, we assessed the lineage composition of donor-derived cells in engrafted animals at 12 weeks after transplant, and found no differences across experimental groups (supplemental Figure 6E). This analysis also confirmed the absence of HSPC chimerism in the BM of tdTomato− recipients and the presence of donor-derived HSPCs in 5 of 6 tdTomato+ and 3 of 4 “high donor number” tdTomato− recipients (Table 1). These results align with immunophenotypic assessments showing higher HSC frequency within tdTomato+ LinloKit+ BM cells as compared with tdTomato− counterparts (Figure 2B) and additionally demonstrate that in situ AAV-CRISPR–edited HSCs sustain intact lineage output and engraftment potential.

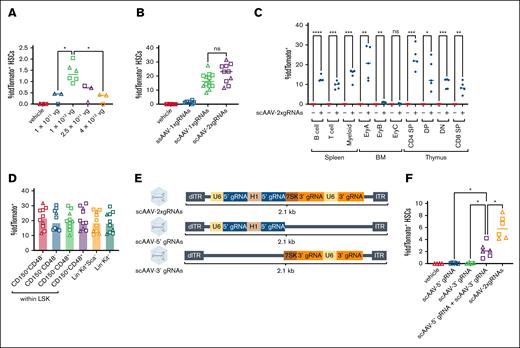

In situ HSC editing in neonates

To explore the adaptability of AAV-mediated in situ HSC editing in an earlier developmental context, we injected neonatal P1 to P3 Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice with vehicle alone or AAV vectors and performed tissue analyses 8 weeks later. To establish optimal dosage for HSC editing in neonates, we tested a range of ssAAV-1xgRNAs doses. A dose of 1 × 1012 vg per animal (equivalent to ∼8.4 × 1014 vg/kg) yielded the highest levels of HSC editing (1.4% ± 0.4%) in animals injected at P1 to P3 (Figure 3A), with both lower and higher doses producing fewer tdTomato+ HSCs. Strikingly, use of the scAAV-2xgRNAs design resulted in tdTomato expression in 22% ± 6.9% of BM HSCs (Figure 3B). Similar to adult injected animals, multiple hematopoietic cell types in the spleen, BM, and thymus of neonatally injected animals receiving scAAV-2xgRNAs exhibited tdTomato expression (Figure 3C). However, unlike adult injected animals (Figure 2A-B), neonatally injected animals exhibited equivalent frequencies of tdTomato+ cells among HSCs and less primitive progenitors; HSCs and other LSK progenitors were also represented comparably within the tdTomato− and tdTomato+ LinloKit+ fractions (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 7). Longitudinal body weight, liver histopathology, and serum inflammatory marker analysis of neonatally injected animals did not indicate any persisting complications due to AAV-CRISPR exposure (supplemental Figure 8A-E). Importantly, analysis of AAV vector copy number in the liver, a tissue that is highly transduced by AAV8, in mice injected with these different vector formats showed comparable representation of AAV vg (supplemental Figure 9), confirming that differences in HSC editing seen with different vector formats do not result from differences in the titration, infectivity, or quality of the distinct vector preparations.

Robust in situ HSC gene editing in neonatally injected mice. (A) Percentage TdTomato+ among BM HSCs at 8 weeks after injection of P1 to P3 neonates. Animals received vehicle control or the indicated dose (vg) of ssAAV-1xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05. Data compiled from 3 independent experiments. (B) Comparison of percentage tdTomato+ HSCs in animals receiving vehicle or 1 × 1012 vg per mouse of either ssAAV-1xgRNAs or scAAV-1xgRNAs or scAAV-2xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. (C) Frequency of TdTomato+ cells among different cell lineages in the spleen, BM, and thymus of animals injected with vehicle or 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV-2xgRNAs. B cell, B220+; T cell, CD3+; myeloid, B220−CD3−; EryA, CD71highTer119+; EryB, CD71intermediateTer119; EryC, CD71−Ter119+; CD4 SP, CD3+CD4+CD8−; DP, CD3+CD4+CD8+; DN, CD3+CD4−CD8−; and CD8 SP, CD3+CD4−CD8+. Unpaired t test with Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. (D) Frequency of TdTomato+ cells among downstream BM progenitors in animals that received 1 × 1012 vg scAAV-2xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. (E) Design of dual AAV vectors delivering separated CRISPR editing components. (F) Frequency of TdTomato+ HSCs in single or dual AAV delivery groups in neonatally injected Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP at 8 weeks after injection. Neonates were injected systemically with vehicle or with 2 × 1011 vg per animal of either scAAV-5′ gRNA only or scAAV-3′ gRNA only or scAAV-5′ gRNA and scAAV-3′ gRNA together or scAAV-2xgRNAs (ie, scAAV delivering 5′ gRNA and 3′ gRNA in 1 vector). One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05. Data compiled from 2 independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. dITR, defective inverted terminal repeat; ITR, inverted terminal repeat. Panel E created with biorender.com. Karimzadehfard A. (2025) https://biorender.com/3vjs8fl.

Robust in situ HSC gene editing in neonatally injected mice. (A) Percentage TdTomato+ among BM HSCs at 8 weeks after injection of P1 to P3 neonates. Animals received vehicle control or the indicated dose (vg) of ssAAV-1xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05. Data compiled from 3 independent experiments. (B) Comparison of percentage tdTomato+ HSCs in animals receiving vehicle or 1 × 1012 vg per mouse of either ssAAV-1xgRNAs or scAAV-1xgRNAs or scAAV-2xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. (C) Frequency of TdTomato+ cells among different cell lineages in the spleen, BM, and thymus of animals injected with vehicle or 5 × 1012 vg per animal scAAV-2xgRNAs. B cell, B220+; T cell, CD3+; myeloid, B220−CD3−; EryA, CD71highTer119+; EryB, CD71intermediateTer119; EryC, CD71−Ter119+; CD4 SP, CD3+CD4+CD8−; DP, CD3+CD4+CD8+; DN, CD3+CD4−CD8−; and CD8 SP, CD3+CD4−CD8+. Unpaired t test with Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. (D) Frequency of TdTomato+ cells among downstream BM progenitors in animals that received 1 × 1012 vg scAAV-2xgRNAs. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. Data compiled from 4 independent experiments. (E) Design of dual AAV vectors delivering separated CRISPR editing components. (F) Frequency of TdTomato+ HSCs in single or dual AAV delivery groups in neonatally injected Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP at 8 weeks after injection. Neonates were injected systemically with vehicle or with 2 × 1011 vg per animal of either scAAV-5′ gRNA only or scAAV-3′ gRNA only or scAAV-5′ gRNA and scAAV-3′ gRNA together or scAAV-2xgRNAs (ie, scAAV delivering 5′ gRNA and 3′ gRNA in 1 vector). One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05. Data compiled from 2 independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. dITR, defective inverted terminal repeat; ITR, inverted terminal repeat. Panel E created with biorender.com. Karimzadehfard A. (2025) https://biorender.com/3vjs8fl.

Altogether, these results demonstrate that higher rates of in situ HSC gene modification, without detectable toxicity, can be achieved using a lower total dose of AAV in neonatally injected animals as compared with adults. Combining data from adult and neonatally injected mice further enabled us to generate a probability model for predicting HSC editing outcome (percentage tdTomato+ HSCs) based on AAV dose at doses below 1.5 × 1015 vg/kg (supplemental Figure 10). It should be noted that this model does not predict editing in neonatally injected animals treated with very high AAV doses (ie, 4 × 1012 vg per animal; ∼3 × 1015 vg/kg), in which we found lower genome editing (Figure 3A), likely due to toxicity associated with high doses of AAV and/or vector aggregation at high concentration. We also evaluated tdTomato induction in skeletal muscle, a nonhematopoietic, nondividing tissue that is transduced very well by AAV8, and observed robust genome editing in both adult and neonatally injected groups (supplemental Figure 11). Together, these results document the utility of AAV-CRISPR delivery as a predictable, tunable strategy for targeting genome editing in primitive and mature hematopoietic cells, as well as nonhematopoietic tissues, of neonatal and adult animals.

Dual AAV transduction of HSCs in situ

Next, we investigated whether in situ HSC genome modification can be achieved in a dual AAV delivery format. We used scAAV vectors carrying only 1 of the 2 gRNAs necessary for gene editing in Ai9 mice to test the cotransduction efficiency of 5′ gRNAs and 3′ gRNAs delivered on separate vectors (Figure 3E). Rare (0.2% ± 0.1%) tdTomato+ HSCs were detected in adult Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP animals coinjected with both 5′ gRNAs and 3′ gRNAs scAAVs, whereas tdTomato+ HSCs were not detected in animals receiving the 5′ gRNAs or the 3′ gRNAs vector alone (supplemental Figure 12). We also delivered the 5′ and 3′ gRNAs vectors alone, or in combination, to neonatal Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice. Again, we detected tdTomato+ HSCs in neonatal animals coinjected with dual vectors carrying separated gRNAs but did not detect tdTomato+ HSCs in mice receiving only 5′ gRNAs or only 3′ gRNAs. Notably, editing rates in mice receiving the all-in-1 scAAV-2xgRNAs vector (6.0% ± 1.8% tdTomato+ HSCs) were only 2.7-fold higher than rates in mice administered dual 5′ gRNAs and 3′ gRNAs vectors (2.2% ± 1.2% tdTomato+ HSCs; Figure 3F). Compared with the adult group, rates of tdTomato induction after AAV cotransduction were ∼1.7-fold greater in neonatally injected animals, suggesting that biological differences between HSCs in neonatal vs adult mice may influence gene editing outcomes. These data establish that HSCs can be cotransduced in situ with dual AAV vectors carrying distinct cargo genes, offering exciting possibilities for combinatorial and multiplexed genome targeting and for split delivery of larger transgenes to endogenous blood progenitors.

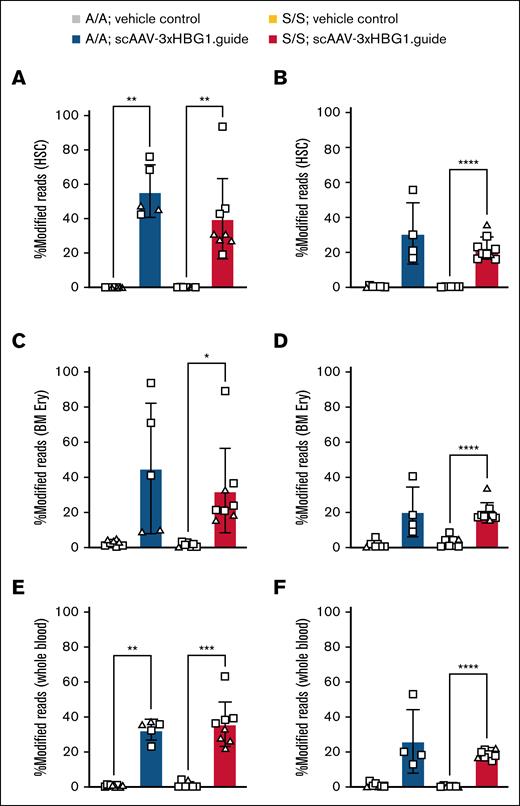

Robust in situ HSC editing in Townes;SpCas9-EGFP mice

Next, we wished to determine whether in situ HSC editing technology might be adapted to a disease-relevant context. We chose Townes SCD mice, in which human HBB, HBA, and HBG replace mouse globin genes.28,29 To adapt this model to our system, we bred Townes animals to mice expressing SpCas9-EGFP, generating Townes;SpCas9-EGFP multiallelic animals. We used gRNAs designed to disrupt the BCL11A binding motif within the transgenic human sequences in the HBG1 promoter of these mice, a strategy well documented to elevate therapeutic HbF levels (supplemental Figure 13A) in vivo.30-34

To mitigate potential toxicity from high vector doses,35,36 we maintained the AAV dose <2 × 1014 vg/kg for these proof-of-concept studies. Adult Townes;SpCas9-EGFP animals (healthy HBBA/A or sickle homozygote HBBS/S) were injected IV with an average of 3 × 1012 vg per animal of scAAV-3xHBG1.gRNA vector, or with vehicle alone, and analyzed 3 months after injection by amplicon-targeted sequencing. Within the HSC compartment, we detected editing rates of 56.2% ± 15.2% for HBBA/A and 40.0% ± 23.34% for HBBS/S in the AAV-injected groups, whereas vehicle control groups lacked detectable gene editing (Figure 4A).

Efficient HSC editing at the HBG1 promoter in Townes;SpCas9-EGPF animals.HBBA/A and HBBS/S animals were IV injected as adults (A,C,E) or neonates (B,D,F) with vehicle or scAAV-3xHBG1.gRNA and analyzed 12 weeks after injection. Approximately 4 × 1012 vg per animal was used for adults and ∼2 × 1011 vg per animal was used for neonates. HBG1 promoter modification in HSCs of adult injected (panel A) or neonatally injected (panel B) animals. HBG1 promoter modification in BM Ery progenitors from adult injected (panel C) or neonatally injected (panel D) animals. HBG1 promoter modification in whole blood from adult injected (panel E) or neonatally injected (panel F) animals and analyzed 12 weeks after injection. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 4 (panels A,C,E) or 3 (panels B,D,F) independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. A/A, healthy HBBA/A; BM Ery, BM erythroid; S/S, sickle homozygote HBBS/S.

Efficient HSC editing at the HBG1 promoter in Townes;SpCas9-EGPF animals.HBBA/A and HBBS/S animals were IV injected as adults (A,C,E) or neonates (B,D,F) with vehicle or scAAV-3xHBG1.gRNA and analyzed 12 weeks after injection. Approximately 4 × 1012 vg per animal was used for adults and ∼2 × 1011 vg per animal was used for neonates. HBG1 promoter modification in HSCs of adult injected (panel A) or neonatally injected (panel B) animals. HBG1 promoter modification in BM Ery progenitors from adult injected (panel C) or neonatally injected (panel D) animals. HBG1 promoter modification in whole blood from adult injected (panel E) or neonatally injected (panel F) animals and analyzed 12 weeks after injection. One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 4 (panels A,C,E) or 3 (panels B,D,F) independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. A/A, healthy HBBA/A; BM Ery, BM erythroid; S/S, sickle homozygote HBBS/S.

We also explored neonatal delivery in this setting, evaluating a high dose (∼5 × 1014 vg/kg; 8 × 1011 vg per animal) and a low dose (1.3 × 1014 vg/kg; 2 × 1011 vg per animal) of the scAAV-3xHBG1.gRNA vector. Possibly due to the contribution of preexisting SCD-related pathologies in HBBS/S neonates, the high vector dose was not tolerated by these animals, whereas it was partially tolerated by HBBA/A counterparts. Lower vector doses were better tolerated by both groups, comparable with the Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP model (supplemental Table 3). We assayed neonatally injected animals 3 months after injection and found modifications at the BCL11A binding motif in HSCs at an average frequency of 30.5% ± 17.6% for HBBA/A and 22.3% ± 6.4% for HBBS/S genotypes (Figure 4B). When normalized to vg per kilogram, these data indicate comparable rates of HSC modification within HBBA/A or HBBS/S groups in adult and neonatally injected animals (supplemental Figure 13B). Sequencing reads for both adult and neonatally injected animals confirmed disruption of the BCL11A binding motif in almost all modified reads and in all animals treated with the scAAV-3xHBG1.gRNA vector (supplemental Figure 13C). Comparison of insertions and deletions detected in adult or neonatally injected HBBS/S animals revealed a higher frequency of large deletions in the neonatally injected group (supplemental Figure 13D). In both age groups, sequencing of sorted BM erythroid progenitors and whole blood revealed significantly higher modification rates in mice injected with scAAV-3xHBG1.gRNA in comparison with vehicle-injected groups (Figure 4C-F). Thus, the AAV-CRISPR system described here supports robust in situ HSC gene modification at a disease-relevant locus.

HbF induction in gene-modified Townes;SpCas9-EGFP animals

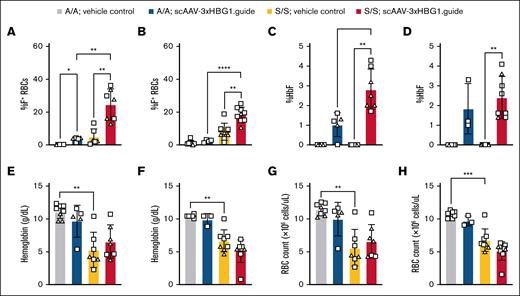

To gauge functional consequences of HBG1 promoter targeting, we assayed HbF levels in animals at 12 weeks after AAV-CRISPR injection. With either adult or neonatal injection, HBBS/S animals receiving scAAV-3xHBG1.gRNA vectors showed higher percentages of HbF-containing RBCs and HbF in blood lysates, compared with vehicle-injected controls (Figure 5A-D; supplemental Figure 14). Despite HbF induction upon vector injection, adult and neonatal HBBS/S animals did not show changes in SCD-associated blood parameters, including hemoglobin level and RBC count, or in gross phenotypic measures such as spleen weight (Figure 5E-H; supplemental Table 4; supplemental Figure 15). These results are consistent with previous observations in Townes model mice37 and confirm the induction of HbF in response to in situ gene modification of hematopoietic cells.

HbF induction in HBG1 promoter edited animals. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of the percentage of RBCs containing HbF (F+) in adult injected (A) and neonatally injected animals (B) at the terminal time point. (C-D) HPLC analysis of percent HbF in blood lysates collected at terminal time point from adult injected (C) and neonatally injected animals (D). (E-F) CBC analysis at the terminal time point for hemoglobin levels (gram/deciliter) in adult injected (E) or neonatally injected animals (F). (G-H) CBC analysis at the terminal time point for RBC count (×106 cells per μL) in adult injected (G) or neonatally injected mice (H). One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 4 (panels A,C,E) or 3 (panels B,D,F) independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. A/A, healthy HBBA/A; S/S, sickle homozygote HBBS/S.

HbF induction in HBG1 promoter edited animals. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of the percentage of RBCs containing HbF (F+) in adult injected (A) and neonatally injected animals (B) at the terminal time point. (C-D) HPLC analysis of percent HbF in blood lysates collected at terminal time point from adult injected (C) and neonatally injected animals (D). (E-F) CBC analysis at the terminal time point for hemoglobin levels (gram/deciliter) in adult injected (E) or neonatally injected animals (F). (G-H) CBC analysis at the terminal time point for RBC count (×106 cells per μL) in adult injected (G) or neonatally injected mice (H). One-way ANOVA with Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Data compiled from 4 (panels A,C,E) or 3 (panels B,D,F) independent experiments. Females, square; males, triangles. A/A, healthy HBBA/A; S/S, sickle homozygote HBBS/S.

Discussion

We report here the use of AAV8 to deliver CRISPR gRNAs for efficient in situ gene editing of HSCs and highlight the scAAV format and greater gRNA:Cas9 ratio as features that can enhance editing rates. Elegant systems have used adenoviral vectors to edit HSC genomes in vivo with high efficiencies, although this approach requires HSC mobilization, enrichment by drug selection, and human CD46 transgenic animals.38-42 Here, we described a complementary AAV-based system that enables efficient in situ HSC gene editing with the introduction of a single immune-tolerated vector in an otherwise unperturbed physiological environment. The system described here can be leveraged for in vivo genetic screens, for modeling of monogenic blood disorders, and for investigating the consequences of DNA damage and mutations in HSCs and HSPCs in situ.

To use our system in a disease context, we chose Townes mice as a highly-relevant model of SCD.28,43-48 Although conditional genetic ablation of BCL11A protein robustly induces HbF levels and rescues disease phenotype in Townes animals,49 recent studies37 using ex vivo disruption of BCL11A binding sites in the HBG promoter, followed by transplantation, failed to efficiently induce HbF. Here, we corroborate these findings in an entirely in vivo setting, demonstrating that robust modification of the BCL11A binding site in endogenous HPSCs results in only modest HbF induction and no therapeutic benefit to SCD phenotypes in Townes mice (Figures 4 and 5), emphasizing an important consideration regarding preclinical SCD mouse models.

In adult injected Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP mice, we found higher frequencies of tdTomato+ cells among more primitive HSC populations than in differentiated BM progenitors (Figure 2A). We also saw higher HSC frequencies within LinloKit+ BM progenitors when comparing the tdTomato+ fraction with tdTomato− counterparts (Figure 2B), which we confirmed functionally in transplantation assays (Table 1). Possible explanations include (1) HSCs are more likely than less primitive progenitors to be gene modified and contribute only gradually to more differentiated cell subsets; (2) upon gene modification in an otherwise unperturbed system, HSCs are less likely than their non–gene-modified counterparts to contribute to the mature blood cell pool; (3) HSCs with higher self-renewal capacity are more likely to be gene edited; or (4) upon gene modification, HSCs exhibit higher self-renewal capacity. Development of an HSC-restricted transduction and/or gene modification system could discriminate among these possibilities. It is also possible that less primitive progenitors may have similar rates of gene modification, yet the outcomes of editing in proliferating downstream progenitors are more likely to disrupt tdTomato expression (eg, by introducing large deletions), as compared with editing outcomes in HSCs, which preferentially incorporate shorter insertions and deletions at sites targeted by CRISPR-Cas9.50,51 Our analysis of large deletions in the Townes;SpCas9-EGFP model is in line with a higher frequency of large deletions in cycling neonatal HSCs than in quiescent adult HSCs (supplemental Figure 13D).

Neonatal and adult mice also showed different editing rates overall in the Ai9;SpCas9-EGFP system, in which injection of neonates with fivefold less vector resulted in an approximate fourfold higher frequency of edited HSCs than adult injected mice (Figures 1E and 3B). AAV dosage (vector genomes per kilogram) seems partially to account for higher editing rates in neonatally injected mice (supplemental Figure 10); yet, other factors, such as differences in HSC proliferation rates,52 immunity,53 and anatomical location,54,55 could also contribute. Interestingly, mobilization of HSCs does not seem to enhance levels of genome editing in adult injected animals18 (supplemental Figure 3).

Future clinical translation of endogenous HSPC editing by AAV-CRISPR will depend on effective delivery of all editing components. Given the size limitations for AAV cargo, codelivery of gene-modifying machinery may be necessary. Dual AAVs have been used to overcome this limitation in nonhematopoietic tissues,56-58 and here we provide direct evidence that BM HSCs also can be cotransduced in situ (Figure 3E-F). We hope these, and other, data in this report will encourage additional efforts to improve the efficiency, specificity, and versatility of in vivo gene editing for hematological applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Roderick Bronson at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Rodent Histopathology Core for expert consultation on liver pathology scoring. Complete blood counts were performed with the assistance of Michelle Lifton at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center’s Center for Virology and Vaccine Research. The authors also thank Angela Wood at the Joslin Diabetes Center’s Diabetes Research Center-funded Flow Cytometry Core (National Institutes of Health [NIH], National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [NIDDK] grant P30DK036836) for supporting cell sorting and analysis studies.

Funding for this work was provided by NIH, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant R01HL135287, NIH, National Institute on Aging grant DP1 AG063419, a Joslin Diabetes Center Graetz Fund Award (A.J.W.), NIH, NIDDK grant T32DK007260-44 (A.K.), and NIH, NHLBI grant R01HL172489 (D.E.B.). D.E.B. also received support from the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Collaborative Research Consortium.

Authorship

Contribution: A.K., T.S., and A.J.W. conceived and designed the experiments; A.K., R.K., V.G., M.F., B.L.P., S.K., D.W., K.M., and J.Z. performed the experiments; J.Z. and D.E.B. provided essential reagents; A.K., A.J.W. R.K., J.Z., and D.E.B analyzed the data and interpreted results; and all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.K., M.F., and A.J.W. are listed as inventors on patent applications related to in vivo gene editing and gene therapy through their institutions, which are related to the systems studied in this study. A.J.W. reports research grants from National Resilience and Sarepta; and consultation fees from Kate Therapeutics for adeno-associate virus work, unrelated to this study. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Amy J. Wagers, Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology, Harvard University, 7 Divinity Ave, Cambridge, MA 02138; email: amy_wagers@harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Amy J. Wagers (amy_wagers@harvard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.