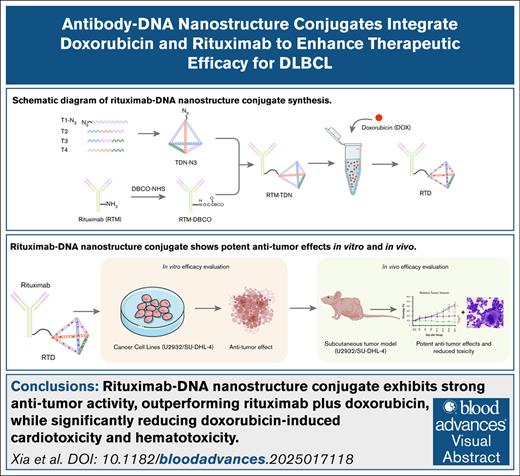

Visual Abstract

The primary clinical approach for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in recent decades has predominantly relied on chemotherapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) as the cornerstone. However, given the highly heterogeneous nature of DLBCL, >30% of patients are prone to relapse and may even exhibit resistance to treatment. Antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) therapies have demonstrated significant advancements in clinical trials targeting DLBCL, thereby indicating a promising direction for its management. By leveraging the inherent modifiability of DNA nanostructures and the affinity of doxorubicin for DNA, we used a combination of rituximab-based R-CHOP scheme and DNA tetrahedra to fabricate antibody-DNA nanostructure conjugate (ADNC). The rituximab-tetrahedron-doxorubicin conjugate (RTD) studied in our research has been validated through in vitro cellular experiments and subcutaneous tumor models. The RTD demonstrated a robust antitumor effect in vitro, significantly exceeding the combined effects of rituximab and doxorubicin by >50-fold. Furthermore, confirmation from a subcutaneous tumor model substantiated the potent antitumor efficacy of RTD while successfully mitigating cardiotoxicity and hematotoxicity associated with doxorubicin. ADNC effectively facilitates the binding of rituximab and doxorubicin in the R-CHOP regimen, offering novel prospects for the development of next-generation ADC drugs.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs), accounting for ∼30% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases worldwide and affecting ∼150 000 individuals annually, typically manifest as progressive lymphadenopathy or extranodal disease.1 Despite most patients being diagnosed at an advanced stage, >60% can achieve a cure through the administration of R-CHOP (rituximab [RTM], cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin [DOX], vincristine, and prednisone) immunochemotherapy.1 Currently, DLBCL treatment encounters 2 primary challenges: first, 40% of patients still experience relapse and exhibit poor survival outcomes after R-CHOP therapy2; and second, the R-CHOP–based treatment regimen using a substantial quantity of chemotherapy drugs may induce severe toxic side effects in patients.3 Therefore, the development of novel therapeutic strategies is currently an imperative.

In the POLARIX phase 3 study, the addition of the anti-CD79b antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) polatuzumab vedotin to the R-CHP backbone led to superior progression-free survival compared to R-CHOP.4 The anti-CD19 ADC loncastuximab tesirine demonstrated significant efficacy in the treatment of relapsed or refractory DLBCL during phase 2 clinical trials.5 This suggests that developing ADC drugs may be an effective strategy to address the current clinical challenges of DLBCL. The monoclonal antibody RTM, which targets CD20, is a crucial component of the R-CHOP regimen.6 However, despite >20 years since its launch, significant progress in developing ADC drugs based on RTM has proven challenging. This difficulty primarily stems from the fact that binding of CD20 with RTM cannot induce effective endocytosis and consequently hinders the smooth release of cytotoxic agents carried by the ADCs.7,8

The DNA tetrahedron, a type of DNA nanostructure, has excellent cell internalization efficiency.9,10 The DNA tetrahedron can be conjugated with RTM via a click chemical reaction, thereby addressing the challenge of RTM in facilitating efficient endocytosis. DOX is a crucial component of R-CHOP and serves as an efficacious chemotherapeutic agent extensively used for the treatment of diverse solid tumors and hematological malignancies.11 However, owing to its nonspecific targeting, DOX often induces severe hematotoxicity and cardiotoxicity during the course of treatment.12 DOX has the ability to insert and bind to DNA double-helix structures13 and can bind to DNA tetrahedra to achieve drug delivery.

In our prior research, we developed an antibody-DNA nanostructure conjugate (ADNC) that facilitates efficient transmembrane drug delivery and has successfully progressed to preclinical studies.14 In this study, we used a click chemical reaction to conjugate RTM with DNA tetrahedra and coincubated it with DOX for drug loading, thereby preparing ADNCs. This novel form of ADC drug not only addresses the issue of low internalization efficiency associated with RTM but also endows DOX with targeting capabilities. In both in vivo and in vitro experiments, the conjugates we designed exhibited stronger pharmacological effects than DOX and did not exhibit the significant blood and cardiac toxicities associated with DOX. This design will have a positive driving effect on the improvement of clinical treatment plans for DLBCL.

Materials and methods

RTD synthesis

RTM (Roche, Rituximab) was purified via a 50 kDa ultrafiltration tube and subsequently incubated with dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) (HY-42973; MedChemExpress) at a 1:2 ratio in 0.1-M NaHCO3 buffer (Sangon Biotech; A610482) at 4°C overnight. After incubation, the mixture was concentrated using the same ultrafiltration method to obtain RTM-DBCO. The concentration was determined by measuring the UV absorption peak at 280 nm. RTM-DBCO was then reacted with TDN (Tetrahedron) in a 1:1 ratio in phosphate-buffered saline (pH = 7) at 4°C overnight to synthesize RTM-TDN. The resultant RTM-TDN was mixed with DOX at a 1:20 ratio to produce the RTM-tetrahedron-DOX conjugate (RTD) at room temperature for 5 minutes.

Cell culture

The diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cell lines SU-DHL-4 and U2932, procured from the ATCC (American Type Culture Collection) cell repository, underwent STR (Short Tandem Repeat) profiling and mycoplasma testing before initiating experiments in March 2023. SU-DHL-4 cells were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (Gibco; 12440053) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; 12484028) and 2% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco; 15140148). U2932 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco; 11875093) with the same supplements. Both cell lines were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

PDX models

Tumor samples were collected from patients with DLBCL under a research protocol approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Fudan University Affiliated Cancer Center (050432-4-2108). The xenograft models were developed in 4-week-old male NCG (NOD/ShiLtJGpt-Prkdcem26Cd52Il2rgem26Cd22/Gpt) mice obtained from GemPharmatech (catalog no. T001475). Three different patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of DLBCL were established using the same experimental approach as described in the literature.15 When the tumor tissue reaches a stable proliferative state within the model organism and attains a volume of ∼50 mm3 (supplemental Figure 14), it is excised, sectioned into equal-volume fragments, and subsequently inoculated into new NCG mice. Once the PDXs were successfully established, they were further propagated in a total of 20 NCG male mice to meet experimental requirements. When the median tumor volume surpassed 5 mm3, treatments were initiated in 6 mice per group through IV tail vein injections every 2 days at a dose of 5 μL/g. The treatment regimens consisted of vehicle control (phosphate-buffered saline), a combination therapy of DOX (54 μM) and RTM (3 μM), or RTD (3 μM). Tumor sizes and mouse body weights were monitored on a weekly basis. The study concluded when tumor volumes reached >50 mm3 or <1 mm3.

Clinical information and molecular biology characteristics are reported in supplemental Table 2 and supplemental Figures 10-13. Two of the models (DLBCL1 and DLBCL2) were established from patients with primary DLBCL and DLBCL3 was established from patients with recurrent DLBCL who were resistant to conventional chemotherapy (including R-CHOP).

Statistical analysis

The mean ± standard deviation was used to present data, unless stated otherwise. Unpaired t tests were used for analyzing group differences, whereas 1-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons involving ≥3 groups using GraphPad prism 8.0 software. A significant level of P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of RTD

RTM was purified using ultrafiltration tubes and subsequently modified with DBCO, as depicted in Figure 1A. Simultaneously, 4 DNA single strands were subjected to a heating annealing reaction to form DNA tetrahedra–containing azide groups (TDN-N3). The 2 components were mixed and incubated at low temperature overnight to obtain RTM-TDN. Taking advantage of DOX's affinity for double-stranded DNA,13 dissolved DOX was combined with RTM-TDN to yield RTD. The results of nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis demonstrated that the size of TDN increased upon coupling with RTM, predominantly localized in the upper gel layer (supplemental Figure 1C). Furthermore, there was no significant alteration in electrophoretic mobility after its combination with DOX (supplemental Figure 1D). Additionally, TDN-DOX exhibits excellent structural stability, which can be maintained for >6 months (supplemental Figure 1F). These findings suggest that the incorporation of DOX did not disrupt the overall structural integrity of RTD. The results of particle size analysis and negative staining electron microscopy also confirmed that the overall particle size of RTD is ∼18 nm (supplemental Figure 1A-B).

Apoptosis induced by RTD. (A) Schematic diagram of RTD synthesis. TDN indicates the complete DNA tetrahedral structure. RTM-TDN is the product of RTM conjugated to the DNA tetrahedron via click chemistry. RTD represents RTM-TDN with DOX incorporated at a 1:20 ratio. (B) The proliferation inhibition curve of SU-DHL-4 cells by RTD. (C) The proliferation inhibition curve of U2932 cells by RTD. The ratio of RTM+DOX mixture is 1:20. (D) Flow cytometry scatterplot of RTD-induced apoptosis in SU-DHL-4 cells. (E) Flow cytometry scatterplot of RTD-induced apoptosis in U2932 cells. (F) Statistical analysis of apoptosis in Q2 and Q3 from panel D. (G) Statistical analysis of apoptosis in Q2 and Q3 from panel E. The results of histogram from panels F-G are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3; not significant [ns]; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (H) Western blot analysis of pro–caspase 3 and cleaved caspase 3 proteins. The uncropped image is displayed in the supplement Information (supplemental Figures 2 and 3). (I) Quantification of pro–caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in SU-DHL-4 cells. (J) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in SU-DHL-4 cells. (K) Quantification of pro–caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in U2932 cells. (L) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in U2932 cells. The total protein was used as the standard for normalization and processed using Image Lab software. The results of histogram from panels I-L are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration value; ns, not significant.

Apoptosis induced by RTD. (A) Schematic diagram of RTD synthesis. TDN indicates the complete DNA tetrahedral structure. RTM-TDN is the product of RTM conjugated to the DNA tetrahedron via click chemistry. RTD represents RTM-TDN with DOX incorporated at a 1:20 ratio. (B) The proliferation inhibition curve of SU-DHL-4 cells by RTD. (C) The proliferation inhibition curve of U2932 cells by RTD. The ratio of RTM+DOX mixture is 1:20. (D) Flow cytometry scatterplot of RTD-induced apoptosis in SU-DHL-4 cells. (E) Flow cytometry scatterplot of RTD-induced apoptosis in U2932 cells. (F) Statistical analysis of apoptosis in Q2 and Q3 from panel D. (G) Statistical analysis of apoptosis in Q2 and Q3 from panel E. The results of histogram from panels F-G are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3; not significant [ns]; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (H) Western blot analysis of pro–caspase 3 and cleaved caspase 3 proteins. The uncropped image is displayed in the supplement Information (supplemental Figures 2 and 3). (I) Quantification of pro–caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in SU-DHL-4 cells. (J) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in SU-DHL-4 cells. (K) Quantification of pro–caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in U2932 cells. (L) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in U2932 cells. The total protein was used as the standard for normalization and processed using Image Lab software. The results of histogram from panels I-L are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration value; ns, not significant.

To verify the stability of RTD, we coincubated serum with TDN and TDN-DOX. The results showed that after 12 hours of coincubation, there were still a large number of structurally intact TDN and TDN-DOX, and the difference between the 2 was not significant (supplemental Figure 1E). This indicates that DOX binding to TDN does not disrupt its structural integrity or affect its degradation, which is an important prerequisite for the smooth release of drugs. Due to its exceptional fluorescence properties, DOX experiences fluorescence quenching upon binding to DNA double-stranded structures.16 By varying the molar ratios of DOX and TDN in the mixture, the results from the fluorescence spectrum demonstrate that DOX exhibits an emission peak at 590 nm (supplemental Figure 1E). When combined with TDN at a molar concentration of 1 or 20 times, the emission peak becomes indiscernible (supplemental Figure 1E). However, when combined with TDN at a molar concentration 50 times higher, the emission peak becomes weaker than that of DOX at an equivalent concentration (supplemental Figure 1E). This suggests that complete binding between DOX and TDN occurs when their concentrations are in a ratio of 20 moles to 1 mole; whereas after binding with 50 moles of TDN, free DOX still remains. This is consistent with the phenomenon of concentrating RTD in a 50 kDa ultrafiltration tube, where the RTD is mainly located in the inner tube (supplemental Figure 1E). Therefore, we adopted a molar ratio of 20:1 between DOX and RTM-TDN for further research. This means that the drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) of RTD can reach 20. In summary, RTD cannot only be effectively synthesized but also has appreciable stability and drug-loading ability.

RTD effectively inhibits the proliferation of DLBCL cells

To evaluate the inhibitory effect of RTD on DLBCL, we selected germinal center B cell (SU-DHL-4) and activated B cell (U2932) as cell models.17,18 In SU-DHL-4 cells, RTM has almost no significant inhibitory effect, whereas the 50% inhibitory concentration value of RTD is nearly half of TDN-DOX, one thirty-sixth of RTM/DOX mixture, and one fiftieth of DOX (Figure 1B). The data indicate that the mechanism of action of DOX loaded onto RTM-TDN demonstrates a significant antitumor effect. Similarly, in U2932 cells, RTD exhibited the same inhibitory effect (Figure 1C). The inhibitory effects of DOX have been extensively demonstrated in numerous studies, primarily attributed to its induction of tumor cell apoptosis.19 Therefore, we used flow cytometry to assess cellular apoptosis. From the scatterplot results, it is evident that the clustering characteristics of dead cells induced by RTD exhibit similarity to those of RTM/DOX mixtures (Figure 1D-G), thereby indicating that the pharmacological effects of RTD in carrying DOX are akin to those of DOX itself. Considering the temporal aspect, there is an increasing proportion of cell apoptosis induced by RTD in SU-DHL-4 and U2932 over time (Figure 1D-G). Furthermore, with respect to the concentration gradient, as the concentration of RTD rises, so does the proportion of cell apoptosis (Figure 1D-G).

To further validate cell apoptosis, we assessed the activation of caspase 3. In SU-DHL-4/U2932 cells, both RTD and RTM/DOX mixtures exhibited an increase in pro–caspase 3 levels, whereas the amount of cleaved caspase 3 also showed a significant elevation (Figure 1H-L). These findings suggest that RTD can effectively induce cell apoptosis, and its mechanism of action resembles that of DOX. Therefore, RTD has a strong inhibitory effect on DLBCL cell lines and its mechanism of action is similar to that of DOX.

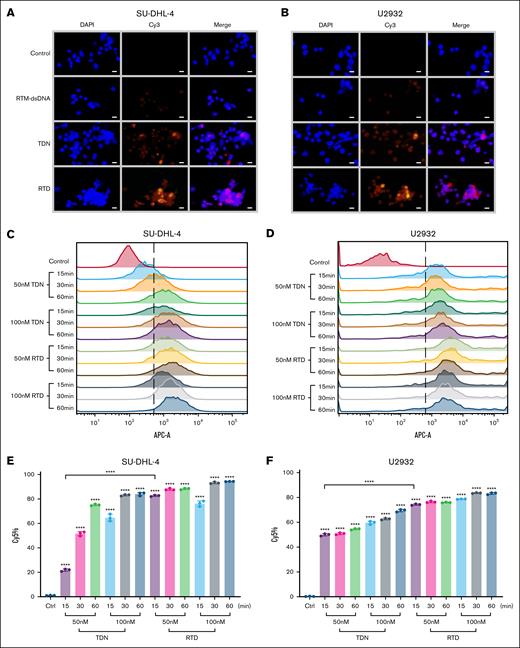

RTD can be effectively internalized by DLBCL cells

The effective endocytosis of ADC by tumor cells is the key to its efficacy. However, previous studies have shown that RTM combined with CD20 cannot mediate efficient endocytosis.7,8 The DNA tetrahedron exhibits excellent intracellular internalization efficiency,9 thereby addressing the limitation of RTM in effectively mediating intracellular endocytosis and offering potential for enhancing the efficacy of RTDs. Through fluorescence imaging, we observed that RTD has similar intracellular internalization ability to TDN, and in both SU-DHL-4 and U2932 cells, Cy5-labeled RTDs were found to be widely distributed within the cells (Figure 2A-B), which is a crucial prerequisite for the therapeutic efficacy of RTD. This finding aligns with the previously mentioned stronger inhibitory effect of RTD on tumor cells than TDN-DOX.

The assessment of tumor cell uptake capacity for RTD. (A) Representative fluorescent microscopy images of SU-DHL-4 (scale bar, 50 μm). (B) Representative fluorescent microscopy images of U2932 (scale bar, 50 μm). (C) Flow histogram of Cy5 positivity after incubating SU-DHL-4 cells with Cy5-labeled TDN/RTD. (D) Flow histogram of Cy5 positivity after incubating U2932 cells with Cy5-labeled TDN/RTD. (E) Statistical analysis of Cy5 positive cells from panel C. (F) Statistical analysis of Cy5 positive cells from panel D. The results of histogram from panels E-F are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. Unpaired t test was used for comparison between 2 groups.

The assessment of tumor cell uptake capacity for RTD. (A) Representative fluorescent microscopy images of SU-DHL-4 (scale bar, 50 μm). (B) Representative fluorescent microscopy images of U2932 (scale bar, 50 μm). (C) Flow histogram of Cy5 positivity after incubating SU-DHL-4 cells with Cy5-labeled TDN/RTD. (D) Flow histogram of Cy5 positivity after incubating U2932 cells with Cy5-labeled TDN/RTD. (E) Statistical analysis of Cy5 positive cells from panel C. (F) Statistical analysis of Cy5 positive cells from panel D. The results of histogram from panels E-F are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. Unpaired t test was used for comparison between 2 groups.

To gain a deeper understanding of the intracellular internalization efficiency of RTD, we used flow cytometry for quantitative analysis. From a cellular perspective, at a concentration of 50-nM TDN, ∼80% of U2932 cells exhibited positivity within 15 minutes, whereas <50% of SU-DHL-4 cells displayed the same response (Figure 2C-F). However, as time progressed and TDN concentration increased, no significant disparity was observed between the 2 cell lines, with >80% of cells exhibiting positivity (Figure 2C-F). These findings suggest that U2932 demonstrates faster uptake kinetics for TDN than SU-DHL-4 initially. Unlike TDN, RTD has a positivity rate of >80% in both cell types, and there is no significant difference between the 2 cell lines (Figure 2C-F). Regardless of concentration gradient or time gradient, the positivity rate of RTD in the 2 cell lines exceeded 80% (Figure 2C-F). This indicates that RTD can bind to cells faster than TDN, promoting intracellular uptake of the entire drug structure.

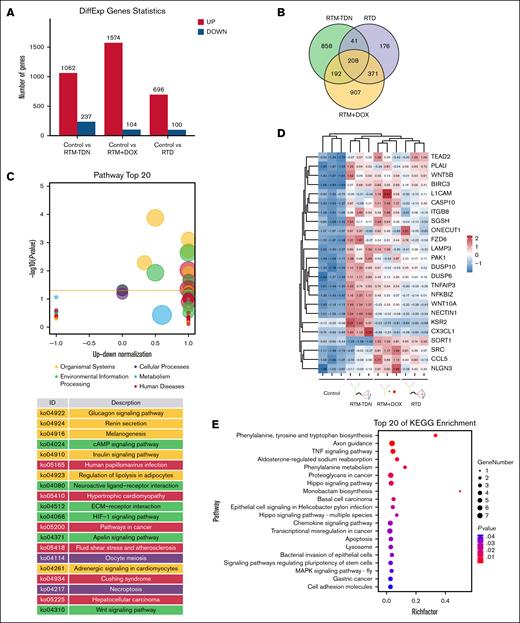

The transcriptomic regulation of RTD exhibits similarities to that observed in RTM/DOX mixture

Through transcriptome sequencing, we compared the regulatory network of RTD in SU-DHL-4 cells with other experimental groups. From the statistical analysis of differentially expressed genes, it is evident that the RTM/DOX mixture induces a significantly higher number of differentially expressed genes, particularly those that are upregulated (Figure 3A). The results obtained from the Wayne plot demonstrate that there are 208 common differentially expressed genes among the 3 experimental groups, whereas the RTD group exhibits 176 unique differentially expressed genes (Figure 3B). The common differentially expressed genes in the 3 experimental groups exhibit a diverse array of mechanisms, and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analysis reveals that these genes primarily participate in metabolic processes (eg, SGSH and ONECUT1), tumor necrosis factor signaling pathway (eg, CCL5 and CX3CL1), WNT signaling pathway (eg, WNT5B, FZD6, and WNT10A), Hippo signaling pathway (eg, TEAD2), apoptosis (eg, BIRC3, CASP10, and PAK1), and lysosomal functions (eg, LAMP3; Figure 3C-E). The heat map depicting the expression patterns of these differentially expressed genes demonstrates strikingly similar regulatory characteristics between the RTD group and the RTM/DOX mixture group (Figure 3C-E). This suggests that both drug groups exert their effects through comparable mechanisms.

Analysis of transcriptome regulation induced by RTD. (A) Statistical analysis of differentially expressed genes. (B) The Venn diagram displays differentially expressed genes. (C) The z score bubble plot analysis of 176 unique differentially expressed genes induced by RTD. (D) Heat map analysis of representative common differentially expressed genes. (E) KEGG enrichment bubble chart of 208 common differentially expressed genes. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Analysis of transcriptome regulation induced by RTD. (A) Statistical analysis of differentially expressed genes. (B) The Venn diagram displays differentially expressed genes. (C) The z score bubble plot analysis of 176 unique differentially expressed genes induced by RTD. (D) Heat map analysis of representative common differentially expressed genes. (E) KEGG enrichment bubble chart of 208 common differentially expressed genes. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

For the 176 unique differentially expressed genes induced by RTD, KEGG enrichment analysis revealed their predominant upregulation of the cAMP signaling pathway (eg, EDN1 and ADRB2; Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 4). Unlike RTD, the 907 unique differentially expressed genes in the RTM/DOX mixture group exhibited a prominent upregulation of ABC (ATP-binding cassette) transporters and a downregulation of histone expression (supplemental Figure 5). The overexpression of ABC transporter proteins can enhance both intracellular and extracellular excretion of DOX, thereby promoting drug resistance in tumor cells.20,21 Therefore, administering DOX in the form of RTD can mitigate this mechanism, which could have implications for more prolonged use of RTD than DOX.

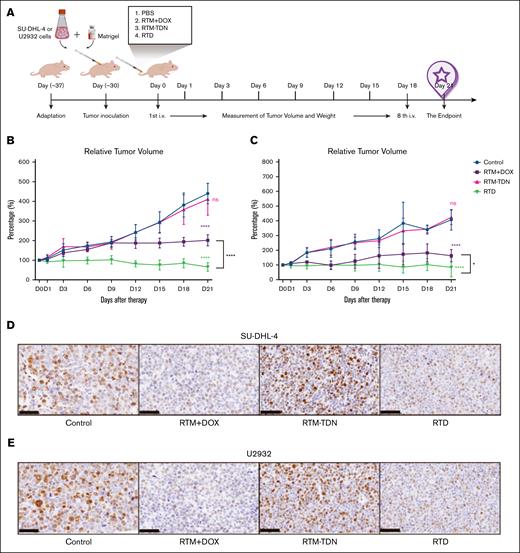

RTD exhibits strong inhibitory effects in the DLBCL tumor model

We confirmed the in vivo antitumor efficacy of RTD by establishing a subcutaneous tumor model. After acclimatization, nude mice were subcutaneously injected with SU-DHL-4 and U2932 cells (Figure 4A). After 30 days of cultivation, they were randomly assigned to groups based on tumor size and body weight (Figure 4A). Each experimental group received tail vein injections every 3 days (Figure 4A). The tumor volume reveals that RTM-TDN does not exert a significant impact on tumor growth, whereas RTD and RTM/DOX mixture exhibit a pronounced inhibitory effect on tumor growth (Figure 4B-C; supplemental Figure 9C). The temporal profile of tumor changes demonstrates that RTD displays remarkable tumor-inhibiting effects in both types of tumors by day 9, and when compared to the RTM/DOX mixture, the antitumor efficacy of RTD surpasses that of the latter (Figure 4B-C; supplemental Figure 9C). These findings align with those obtained from in vitro cell experiments, indicating that DOX loaded onto RTD can more effectively elicit antitumor effects in tumor models.

Evaluation of the antitumor effect of RTD in vivo. (A) Schematic diagram of subcutaneous tumor model construction. (B) The change curve of SU-DHL-4 tumor tissue. (C) The change curve of U2932 tumor tissue. The results of histogram from panels B-C are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. (D) Representative Ki67 immunohistochemical staining of SU-DHL-4 tumor tissue. (E) Representative Ki67 immunohistochemical staining of U2932 tumor tissue. ns, not significant.

Evaluation of the antitumor effect of RTD in vivo. (A) Schematic diagram of subcutaneous tumor model construction. (B) The change curve of SU-DHL-4 tumor tissue. (C) The change curve of U2932 tumor tissue. The results of histogram from panels B-C are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. (D) Representative Ki67 immunohistochemical staining of SU-DHL-4 tumor tissue. (E) Representative Ki67 immunohistochemical staining of U2932 tumor tissue. ns, not significant.

We excised tumor cells from the animal model and conducted hematoxylin and eosin staining. The findings revealed significant reduction in cellularity and matrix laxity in SU-DHL-4 and U2932 tumor tissues treated with RTD or a mixture of RTM/DOX, whereas the RTM-TDN group resembled the control group with abundant tumor cells and a compact matrix (supplemental Figure 6). Immunohistochemical analysis of Ki67 demonstrated markedly weaker positive signals in tumor tissues from the RTD group and RTM/DOX mixture group than both the control and RTM-TDN groups (Figure 4D-E), indicating that RTD and RTM/DOX mixture can elicit similar antitumor effects in animal models, effectively inhibiting both germinal center B-cell (SU-DHL-4) and activated B-cell (U2932) proliferation.

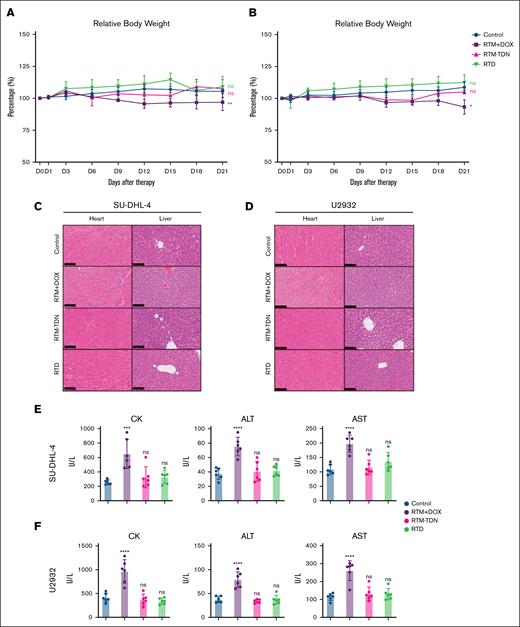

RTD effectively avoids the toxic side effects of DOX

As a clinical drug, the tissue distribution of DOX has been confirmed, mainly distributed in the liver, kidneys, and heart.22 The tissues with high distribution of RTD, in addition to tumor tissues, are mainly the liver and kidneys (supplemental Figure 6C-D), and RTD exhibits a short half-life characteristic (supplemental Figure 6E), which is similar to the pharmacokinetic profile of nucleic acids.10,23 In addition to effectively exerting the antitumor activity of DOX, a critical concern regarding RTD is its potential for inducing toxic side effects similar to those of DOX. The occurrence of severe cardiotoxicity and hematotoxicity caused by DOX poses a significant challenge in current clinical applications.24,25 Through weight testing of animal models during medication, it can be observed that both SU-DHL-4 and U2932 exhibited significant weight loss in the RTM/DOX mixture group, whereas the RTD group did not demonstrate any substantial weight loss (Figure 5A-B). This suggests that RTD does not induce toxic effects similar to DOX on animal models. The animal model heart tissue was subjected to sectioning and hematoxylin and eosin staining, revealing that the RTM/DOX mixture group exhibited a significant increase in myocardial cell death compared to the control group (Figure 5C-D). However, no notable difference was observed between the RTD heart tissue and the control group (Figure 5C-D). In addition, the liver tissue of the RTM/DOX mixture group also showed significant cytoplasmic dissolution, indicating that the drug combination also had a certain degree of liver toxicity, whereas the RTD group did not show significant changes compared to the control group (Figure 5C-D). The kidneys, lungs, and brain tissues of the mice, however, did not exhibit any significant signs of tissue damage (supplemental Figures 7 and 8). The blood biochemistry results also confirmed that the RTM/DOX mixture induced an elevation in cardiac (creatine kinase) and liver injury indicators (aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase), whereas RTD did not elicit significant alterations in these indicators (Figure 5E-F). The markers of renal injury (Uric Acid, UA; Blood Urea Nitrogen, BUN) were in accordance with the aforementioned results and exhibited no significant alterations (supplemental Figure 9). These findings suggest that RTD does not induce hepatotoxicity and cardiotoxicity associated with DOX.

Cardiotoxicity assessment of RTD. (A) Weight change curve of SU-DHL-4 tumor model. (B) Weight change curve of U2932 tumor model. (C) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of SU-DHL-4 tumor tissues. (D) Representative images of H&E staining of U2932 tumor tissues. (E) Serum biochemistry examination of SU-DHL-4 tumor bearing mice. (F) Serum biochemistry examination of U2932 tumor-bearing mice: CK, ALT, and AST. The results of histogram from panels E-F are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; CK, creatine kinase; ns, no significance.

Cardiotoxicity assessment of RTD. (A) Weight change curve of SU-DHL-4 tumor model. (B) Weight change curve of U2932 tumor model. (C) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of SU-DHL-4 tumor tissues. (D) Representative images of H&E staining of U2932 tumor tissues. (E) Serum biochemistry examination of SU-DHL-4 tumor bearing mice. (F) Serum biochemistry examination of U2932 tumor-bearing mice: CK, ALT, and AST. The results of histogram from panels E-F are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; CK, creatine kinase; ns, no significance.

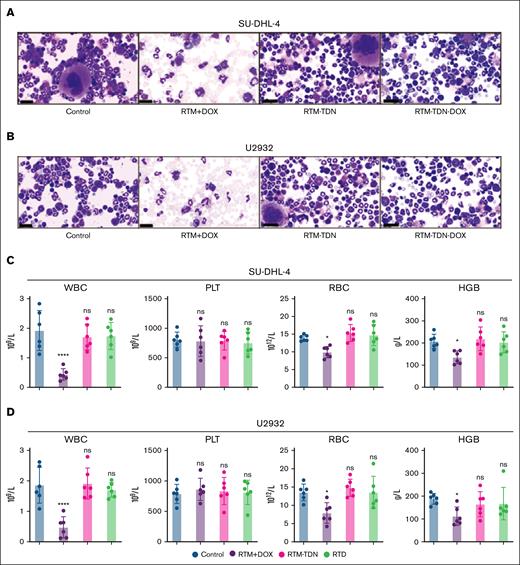

The bone marrow cell smear and Wright staining reveal a significant reduction in the number of nucleated cells in the RTM/DOX mixture group, with a proportion lower than that of mature red blood cells. In contrast, no notable changes are observed in the RTD group compared to the control group (Figure 6A-B). These findings indicate that RTM/DOX induces potent bone marrow suppression in vivo, leading to markedly reduced bone marrow proliferation and corresponding hematotoxicity. The blood cell count results further validate that RTM/DOX induces a significant reduction in white blood cell count in vivo, whereas the white blood cell count in the RTD group remains comparable to that of the control group (Figure 6C-D). This suggests that DOX can be effectively administered in vivo via RTD, thereby mitigating cardiac and hepatic toxicity while circumventing hematological toxicity.

Blood toxicity assessment of RTD. (A) Wright staining of bone marrow cells for SU-DHL-4 tumor model. (B) Wright staining of bone marrow cells for U2932 tumor model. (C) The blood routine examination for SU-DHL-4 tumor model. (D) The blood routine examination for U2932 tumor model: WBC, PLT, RBC, and HGB. The results of histogram from panels C-D are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. HGB, hemoglobin; ns, no significance; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

Blood toxicity assessment of RTD. (A) Wright staining of bone marrow cells for SU-DHL-4 tumor model. (B) Wright staining of bone marrow cells for U2932 tumor model. (C) The blood routine examination for SU-DHL-4 tumor model. (D) The blood routine examination for U2932 tumor model: WBC, PLT, RBC, and HGB. The results of histogram from panels C-D are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. HGB, hemoglobin; ns, no significance; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

RTD exhibits potent antitumor effects in the PDX models

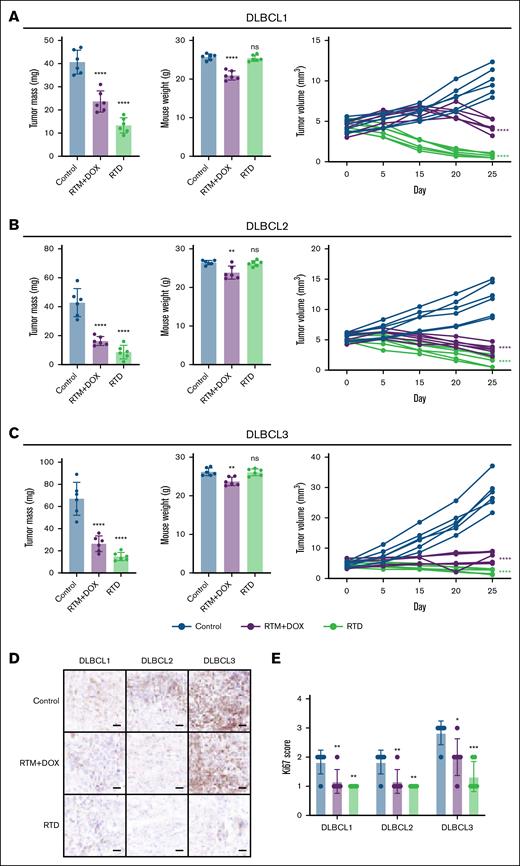

To more comprehensively assess the role of RTD in addressing tumor heterogeneity, we established 3 PDX models (DLBCL1, DLBCL2, and DLBCL3). Notably, the tumor samples for DLBCL3 were obtained from patients with DLBCL who had relapsed after R-CHOP treatment (supplemental Table 2). From the immunohistochemical staining of CD20, it can be seen that the parental sample and PDX sample maintain consistent tissue characteristics and CD20 expression features (supplemental Figure 10). RTD showed consistent antitumor effects in 3 different PDX models and was superior to the effect of the RTM/DOX mixture (Figure 7). In addition, there was no significant difference in body weight between the RTD group and the control group (Figure 7). This indicates that RTD did not cause serious toxic side effects while exerting antitumor effects, which is consistent with the results described earlier.

Efficacy evaluation of RTD on DLBCL PDX model. (A) Efficacy evaluation of RTD on DLBCL1 PDX model. (B) Efficacy evaluation of RTD on DLBCL2 PDX model. (C) Efficacy evaluation of RTD on DLBCL3 PDX model. The left panel presents statistical data on tumors, the center panel illustrates statistics regarding the weight of mice, and the right panel displays the changes in tumor volume over time. (D) Representative Ki67 immunohistochemical imaging (scale bars, 50 μm). (E) Ki67 score statistics. The results from panels A-E are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by Dunnett multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant.

Efficacy evaluation of RTD on DLBCL PDX model. (A) Efficacy evaluation of RTD on DLBCL1 PDX model. (B) Efficacy evaluation of RTD on DLBCL2 PDX model. (C) Efficacy evaluation of RTD on DLBCL3 PDX model. The left panel presents statistical data on tumors, the center panel illustrates statistics regarding the weight of mice, and the right panel displays the changes in tumor volume over time. (D) Representative Ki67 immunohistochemical imaging (scale bars, 50 μm). (E) Ki67 score statistics. The results from panels A-E are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by Dunnett multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant.

The change curve of tumor volume also showed that the tumor volume of the RTD group continuously decreased during the medication period and was better than that of the RTM/DOX mixture group (Figure 7). The immunohistochemical staining results of Ki67 in tumor tissue showed that the positivity rate of Ki67 in the RTD group was lower than that in the control group, indicating that RTD played a potent inhibitory role in tumor cells (Figure 7). This provides important reference value for the clinical application prospects of RTD.

Discussion

ADCs are novel drugs that have achieved multiple successes in clinical practice and are currently undergoing vigorous development, particularly in the treatment of DLBCL.26,27 This study leveraged the advantages of DNA nanostructures (TDN) to construct ADNCs by combining RTM and DOX within the R-CHOP protocol. Typically, ADCs have a DAR of 2 to 428; however, the newly developed T-DXD approaches the upper limit, with a DAR value close to 8.29 In this study, we designed an RTD with an impressive DAR value of up to 20. Moreover, the efficient inhibitory ability of RTD on DLBCL cells was further confirmed by its significant suppression of cell proliferation, surpassing the effects observed with a combination treatment involving RTM/DOX and exhibiting a robust antitumor effect.

The efficacy of RTM primarily relies on antibody-dependent cell–mediated cytotoxicity, complement-dependent cytotoxicity,30 and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis.31 In vitro studies, lacking a complete immune system, result in minimal therapeutic effects of RTM on DLBCL cells. TDN itself demonstrates excellent cellular internalization capability,10 thereby endowing TDN-DOX with tumor cell inhibitory potential similar to that of RTD, which is also confirmed by cell uptake experiments. It is worth noting that although RTM may not effectively mediate cellular endocytosis, RTD demonstrates excellent intracellular internalization efficiency and surpasses TDN in this regard. This can be attributed to 2 main factors: first, the lipid raft effect of RTM facilitates enhanced endocytosis of coupled TDN32; and second, the binding of RTM to CD20 on the cell membrane surface subsequently triggers internalization of the entire structure. Although DOX enters cells in the form of RTD, which is fundamentally distinct from its passive diffusion,33 the pharmacological mechanism of RTD remains analogous to that of DOX.

In vivo studies have additionally demonstrated superior antitumor effects of RTD compared to RTM/DOX mixtures, especially in PDX models. Furthermore, RTD effectively mitigates the cardiotoxicity and hematotoxicity associated with DOX itself.24,34 This can be primarily attributed to 3 factors: first, the coupling of RTM confers targeting properties upon DOX, facilitating enhanced distribution within lesions; second, loading DOX onto RTD results in a larger molecular structure that alters transmembrane transport and impedes penetration into myocardial tissue; and third, the administration method for RTD proves more efficient while requiring lower actual doses of DOX than those used in RTM/DOX mixture group. Some studies have demonstrated that DNA nanostructures can stimulate the activation of the STING signaling pathway, thereby providing potential opportunities for enhancing immunotherapy.14,35 This solution presents an immensely appealing prospect for addressing the current clinical dilemma surrounding DOX.

The ADNC proposed in this study has undergone preliminary validation using DOX and RTM. This design not only enhances the internalization efficiency of RTM but also mitigates the toxic side effects of DOX, resulting in a robust antitumor effect. The preparation of RTD primarily uses click reactions, and DNA nanostructures exhibit excellent assembly efficiency. Using the existing phosphoramidite synthesis method for large-scale preparation of DNA single strands would substantially decrease the synthesis cost of RTD, thereby paving the way for its clinical translation. However, given the disparities in administration methods between mouse models and humans, the dosing frequency and dosage of ADC drugs such as RTD in clinical settings often need to be informed by nonhuman primate models or phase 1 clinical trials. Additionally, the clinical translation of RTD necessitates further preclinical investigation. This innovative combination approach for the R-CHOP regimen has the potential to revolutionize current first-line DLBCL treatment options and provide a safer and more effective alternative for a larger number of patients.

Acknowledgment

Financial support for this study was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 82060040).

Authorship

Contribution: C.L. and Z.X. contributed to conception and design; C.L. and S.L. developed methodology and wrote, reviewed, and/or revised the manuscript; C.L., Y.L., and J.C. acquired data; C.L., J.W., J.C., and J.R. analyzed and interpreted data (eg, statistical analysis, biostatistics, and computational analysis); C.L., S.L., and W.S. provided administrative, technical, or material support (ie, reporting or organizing data and constructing databases); and S.L., Z.X., and W.S. supervised the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Weiqi Sheng, Department of Pathology, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University, Shanghai 200030. China; email: shengweiqi2006@163.com; Chengxun Li, Department of Otolaryngology, Eye & ENT Hospital, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, No. 83, Fenyang Rd, Shanghai 200031, China; email: licx21@m.fudan.edu.cn; and Shengjie Li, Eye & ENT Hospital, Fudan University, No. 83, Fenyang Rd, Shanghai 200031, China; email: lishengjie6363020@163.com.

References

Author notes

Z.X. and J.C. contributed equally to this work.

The data generated in this study are available within the article and its supplemental Data files.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Apoptosis induced by RTD. (A) Schematic diagram of RTD synthesis. TDN indicates the complete DNA tetrahedral structure. RTM-TDN is the product of RTM conjugated to the DNA tetrahedron via click chemistry. RTD represents RTM-TDN with DOX incorporated at a 1:20 ratio. (B) The proliferation inhibition curve of SU-DHL-4 cells by RTD. (C) The proliferation inhibition curve of U2932 cells by RTD. The ratio of RTM+DOX mixture is 1:20. (D) Flow cytometry scatterplot of RTD-induced apoptosis in SU-DHL-4 cells. (E) Flow cytometry scatterplot of RTD-induced apoptosis in U2932 cells. (F) Statistical analysis of apoptosis in Q2 and Q3 from panel D. (G) Statistical analysis of apoptosis in Q2 and Q3 from panel E. The results of histogram from panels F-G are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3; not significant [ns]; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (H) Western blot analysis of pro–caspase 3 and cleaved caspase 3 proteins. The uncropped image is displayed in the supplement Information (supplemental Figures 2 and 3). (I) Quantification of pro–caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in SU-DHL-4 cells. (J) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in SU-DHL-4 cells. (K) Quantification of pro–caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in U2932 cells. (L) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3 protein bands from panel H in U2932 cells. The total protein was used as the standard for normalization and processed using Image Lab software. The results of histogram from panels I-L are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001), compared to control group by 1-way ANOVA. IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration value; ns, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/24/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025017118/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-017118-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1768979908&Signature=PwD0lyW7wZISKuubIC-ZxqfTtEIMGys7Gz5rvFU8ggh~Rn4Rh7GdasuxAIJjAoGYr4FAwbM0LFR97bYZLB~BhaApzwZh3Z-VssU3VTdNGIT5GT3aiEDFvwHddX05TsM8TUIYRqhvXhHzXlh6n4iQU~mgNaLOw20e-uRjHULaKnVTRB1BBZhSqoFAb0t3UFMk2F6Xf64J2qi4QXoivdPEeCq64lUt~7ooOkYBGUXhugHRpq1hljXDDJQek-v6SKwxYOkCNepqLL3ihurV2DCeoW9T4bvnKfRCUSGJfcK70TeDrIcyeajUtR7htTT6MSINHNcI5h36U9USoJle3i-p0A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)